Leukocytosis Associated with Clozapine Treatment: A Case Series and Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Clinical Characterization

3. Results

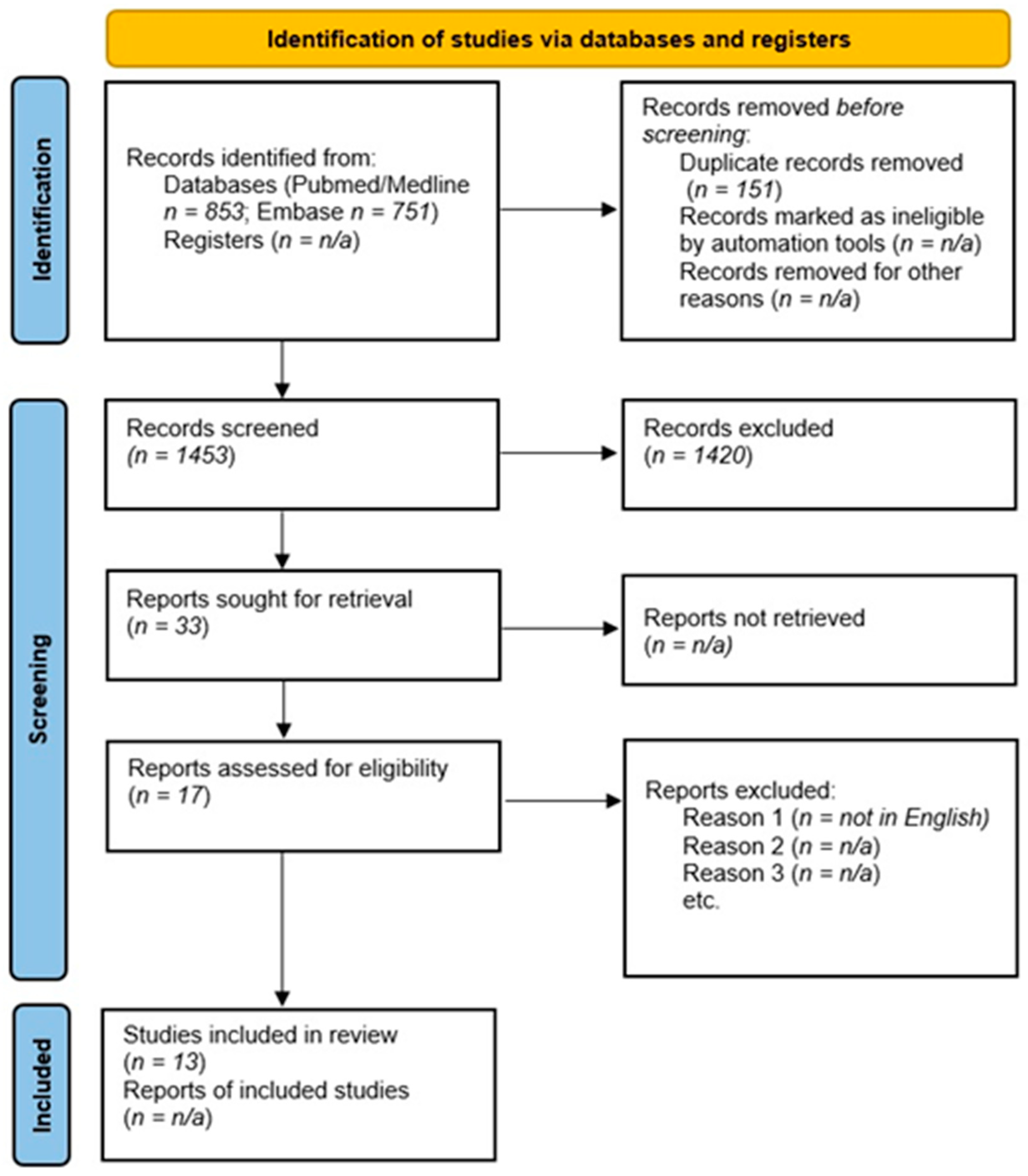

3.1. Results of the Systematic Search

3.2. Case Series

3.2.1. Case 1

3.2.2. Case 2

3.2.3. Case 3

3.2.4. Case 4

3.2.5. Case 5

3.2.6. Case 6

3.2.7. Case 7

3.2.8. Case 8

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Owen, M.J.; Sawa, A.; Mortensen, P.B. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2016, 388, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clozapine: Product Information—European Medical Agency. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/leponex#all-documents-section (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Meltzer, H.Y. Clozapine Treatment for Suicidality in SchizophreniaInternational Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT). Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khokhar, J.Y.; Henricks, A.M.; Sullivan, E.D.; Green, A.I. Unique Effects of Clozapine: A Pharmacological Perspective. Adv. Pharmacol. 2018, 82, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citrome, L.; Volavka, J.; Czobor, P.; Sheitman, B.; Lindenmayer, J.-P.; McEvoy, J.; Cooper, T.B.; Chakos, M.; Lieberman, J.A. Effects of Clozapine, Olanzapine, Risperidone, and Haloperidol on Hostility Among Patients with Schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001, 52, 1510–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volavka, J.; Czobor, P.; Sheitman, B.; Lindenmayer, J.-P.; Citrome, L.; McEvoy, J.P.; Cooper, T.B.; Chakos, M.; Lieberman, J.A. Clozapine, Olanzapine, Risperidone, and Haloperidol in the Treatment of Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakowski, M.I.; Czobor, P.; Citrome, L.; Bark, N.; Cooper, T.B. Atypical Antipsychotic Agents in the Treatment of Violent Patients with Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borek, L.L.; Friedman, J.H. Treating psychosis in movement disorder patients: A review. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2014, 15, 1553–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppes, T.; Webb, A.; Paul, B.; Carmody, T.; Kraemer, H.; Rush, A.J. Clinical outcome in a randomized 1-year trial of clozapine versus treatment as usual for patients with treatment-resistant illness and a history of mania. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 1164–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.M.; Gaughran, F.T.P. The Maudsley Practice Guidelines for Physical Health Conditions in Psychiatry; WILEY Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tiihonen, J.; Lönnqvist, J.; Wahlbeck, K.; Klaukka, T.; Niskanen, L.; Tanskanen, A.; Haukka, J. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: A population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet 2009, 374, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, R.; Downs, J.; Chang, C.-K.; Jackson, R.; Shetty, H.; Broadbent, M.; Hotopf, M.; Stewart, R. The Effect of Clozapine on Premature Mortality: An Assessment of Clinical Monitoring and Other Potential Confounders. Schizophr. Bull. 2015, 41, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vermeulen, J.M.; Van Rooijen, G.; Van De Kerkhof, M.P.J.; Sutterland, A.L.; Correll, C.U.; De Haan, L. Clozapine and Long-Term Mortality Risk in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Studies Lasting 1.1–12.5 Years. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 45, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, H.; Tanskanen, A.; Mehtälä, J.; Vattulainen, P.; Correll, C.U.; Tiihonen, J. 20-year follow-up study of physical morbidity and mortality in relationship to antipsychotic treatment in a nationwide cohort of 62,250 patients with schizophrenia (FIN20). World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bogers, J.P.; Schulte, P.F.; Van Dijk, D.; Bakker, B.; Cohen, D. Clozapine Underutilization in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 36, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, D.L.; Freudenreich, O.; Sayer, M.A.; Love, R.C. Addressing Barriers to Clozapine Underutilization: A National Effort. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kane, J.; Honigfeld, G.; Singer, J.; Meltzer, H. Clozapine for the Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenic. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1988, 45, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, N.; Myles, H.; Xia, S.; Large, M.; Kisely, S.; Galletly, C.; Bird, R.; Siskind, D. Meta-analysis examining the epidemiology of clozapine-associated neutropenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018, 138, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence Rice, M.J. Neutrophilic Leukocytosis, Neutropenia, Monocytosis, and Monocytopenia. Hematol; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 675–681. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.-K.; Bahk, W.-M.; Kwon, Y.J.; Yoon, B.-H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Jon, D.-I.; Park, S.-Y.; Lim, E. F3. A case of leukocytosis associated with clozapine treatment for the management of chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 44, S218–S219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fabrazzo, M.; Prisco, V.; Sampogna, G.; Perris, F.; Catapano, F.; Monteleone, A.M.; Maj, M. Clozapine versus other antipsychotics during the first 18 weeks of treatment: A retrospective study on risk factor increase of blood dyscrasias. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 256, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polat, A.; Cakir, U.; Gunduz, N. Leukocytosis after Clozapine Treatment in a Patient with Chronic Schizophrenia. Arch. Neuropsychiatry 2016, 53, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Takeuchi, H.; Fervaha, G.; Powell, V.; Bhaloo, A.; Bies, R.; Remington, G. The Effect of Clozapine on Hematological Indices. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 35, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Mahgoub, N.; Ferrando, S. Leukocytosis associated with clozapine treatment: A case report. Psychosomatics. 2011, 52, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palominao, A.; Kukoyi, O.; Xiong, G.L. Leukocytosis after lithium and clozapine combination therapy. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 22, 205–206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sopko, M.A.; Caley, C.F. Chronic Leukocytosis Associated with Clozapine Treatment. Clin. Schizophr. Relat. Psychoses 2010, 4, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhusoodanan, S.; Cuni, L.; Brenner, R.; Sajatovic, M.; Palekar, N.; Amanbekova, D. Chronic leukocytosis associated with clozapine: A case series. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 68, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deliliers, G.L. Blood dyscrasias in clozapine-treated patients in Italy. Haematology 2000, 2000, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Popli, A.; Pies, R. Clozapine and Leukocytosis. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1995, 15, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummer, M.; Kurz, M.; Barnas, C.; Saria, A.; Fleischhacker, W.W. Clozapine-induced transient white blood count disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 55, 429–432. [Google Scholar]

- Seifritz, E.; Hemmeter, U.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Pöldinger, W. Chronic Leukocytosis and Neutrophilia Caused by Rehabilitation Stress in a Clozapine-Treated Patient. Pharmacopsychiatry 1993, 26, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.M.; Barnes, T.R.E.; Young, A.H. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry, 14th ed.; WILEY Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tiihonen, J.; Mittendorfer-Rutz, E.; Majak, M.; Mehtälä, J.; Hoti, F.; Jedenius, E.; Enkusson, D.; Leval, A.; Sermon, J.; Tanskanen, A.; et al. Real-World Effectiveness of Antipsychotic Treatments in a Nationwide Cohort of 29 823 Patients with Schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Berardis, D.; Rapini, G.; Olivieri, L.; Di Nicola, D.; Tomasetti, C.; Valchera, A.; Fornaro, M.; Di Fabio, F.; Perna, G.; Di Nicola, M.; et al. Safety of antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia: A focus on the adverse effects of clozapine. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2018, 9, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerson, S.L. Clozapine -- Deciphering the Risks. New Engl. J. Med. 1993, 329, 204–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, J.A.; Kinon, B.J.; Loebel, A.D. Dopaminergic Mechanisms in Idiopathic and Drug-induced Psychoses. Schizophr. Bull. 1990, 16, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinidad, E.D.; Potti, A.; Mehdi, S.A. Clozapine-induced blood dyscrasias. Haematologica 2000, 85, E02. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre, G.; Stewart, R.B. Lithium carbonate and leukocytosis. Am. J. Heal. Pharm. 1980, 37, 1525–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewumi, L.K.; McKnight, M.; Cernovsky, Z.Z. Lithium dosage and leukocyte counts in psychiatric patients. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 1999, 24, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, S.; Shouan, A.; Chakrabarti, S.; Avasthi, A. Haematological side effects associated with clozapine: A retrospective study from India. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 48, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, T.; Omata, F.; Tsuchihashi, K.; Higashioka, K.; Koyamada, R.; Okada, S. Current cigarette smoking is a reversible cause of elevated white blood cell count: Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spina, E.; De Leon, J. Clinical applications of CYP genotyping in psychiatry. J. Neural Transm. 2014, 122, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, S.-F.; Wang, B.; Yang, L.-P.; Liu, J.-P. Structure, function, regulation and polymorphism and the clinical significance of human cytochrome P450 1A2. Drug Metab. Rev. 2009, 42, 268–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevin, S.; Benowitz, N.L. Drug Interactions with Tobacco Smoking. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1999, 36, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondolfi, G.; Morel, F.; Crettol, S.; Rachid, F.; Baumann, P.; Eap, C. Increased Clozapine Plasma Concentrations and Side Effects Induced by Smoking Cessation in 2 CYP1A2 Genotyped Patients. Ther. Drug Monit. 2005, 27, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, J.A.; Herráiz, A.G.; Ramos, S.I.; Gervasini, G.; Vizcaíno, S.; Benítez, J. Role of the Smoking-Induced Cytochrome P450 (CYP)1A2 and Polymorphic CYP2D6 in Steady-State Concentration of Olanzapine. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2003, 23, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focosi, D.; Azzarà, A.; Kast, R.E.; Carulli, G.; Petrini, M. Lithium and hematology: Established and proposed uses. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008, 85, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.M.; Stahl, S.M. The Clozapine Handbook; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Valevski, A.; Modai, I.; Lahav, M.; Weizman, A. Clozapine—lithium combined treatment and agranulocytosis. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1993, 8, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capllonch, A.; De Pablo, S.; De La Torre, A.; Morales, I. Increase in white cell and neutrophil counts during the first eighteen weeks of treatment with clozapine in patients admitted to a long-term psychiatric care inpatient unit. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2018, 11, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehsel, K.; Loeffler, S.; Krieger, K.; Henning, U.; Agelink, M.; Kolb-Bachofen, V.; Klimke, A. Clozapine Induces Oxidative Stress and Proapoptotic Gene Expression in Neutrophils of Schizophrenic Patients. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 25, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røge, R.; Møller, B.K.; Andersen, C.R.; Correll, C.U.; Nielsen, J. Immunomodulatory effects of clozapine and their clinical implications: What have we learned so far? Schizophr. Res. 2012, 140, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri, M.C.; Rudelli, R.; Bravin, S.; Gianetti, S.; Giuliani, E.; Guerrini, A.; Orlandi, R.; Invernizzi, G. Clozapine metabolism rate as a possible index of drug-induced granulocytopenia. Psychopharmacology 1998, 137, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centorrino, F.; Baldessarini, R.J.; Flood, J.G.; Kando, J.C.; Frankenburg, F.R. Relation of leukocyte counts during clozapine treatment to serum concentrations of clozapine and metabolites. Am. J. Psychiatry 1995, 152, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisco, V.; Iannaccone, T.; Di Grezia, G. Radiological assessment of clozapine-induced leukocytosis in two schizophrenic patients. Minerva Psichiatrica 2016, 57, 82–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, J.A.; Kane, J.M.; Safferman, A.Z.; Pollack, S.; Howard, A.; Szymanski, S.; Masiar, S.J.; Kronig, M.H.; Cooper, T.; Novacenko, H. Predictors of response to clozapine. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 55 (Suppl. B), 126–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| References (year) | Study Design | Leukocyte (and Neutrophil) Levels in Units/mm3 | Treatment Duration on Clozapine | Concomitant Pharmacological Treatment Other than Clozapine | Presence of Medical Comorbidities | Demographic Data, Psychiatric Diagnosis, (Clinical Outcome) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [21] | Case report | 22,100; (17,680) | 25 days | Lorazepam | Not applicable | 48 y.o. F; SCZ; (not applicable) |

| [22] | Retrospective cohort study | >15,000; (>7000) | 18 weeks; neutrophilia was observed in 37.8% of the total cohort comprising 145 clozapine-treated individuals | 63 patients received benzodiazepines, 33 mood stabilizers, and 9 antidepressants (concomitant treatment with mood stabilizers or benzodiazepines was associated with transient anemia; co-treatment with antidepressants was associated with transient eosinophilia) | The presence of medical comorbidities did not represent a significant risk factor for the development of neutrophilia | 135 individuals; 70 M, 65 F; 45.1 y.o. among M; 37.9 y.o. among F; 66/135 smokers; 125 SCS, 10 BPS; (persistent neutrophilia was associated with a tendency to lose efficacy over time) |

| [23] | Case report | 24,300; (not available) | 25 days | Not available | No relevant comorbidity was found despite a broad medical evaluation | 41 y.o. F; SCZ; (not applicable) |

| [24] | Retrospective chart review study | (>7500) | One-year study; neutrophilia developed after a median of 6.5 weeks on clozapine; 48.9% cumulative incidence for neutrophilia; neutrophilia preceded neutropenia in three cases of a total of five neutropenia cases | 42/101 individuals on clozapine monotherapy (no significant differences in the development of blood dyscrasias were found with polytherapy vs. clozapine monotherapy) | 33 individuals presented medical comorbidities (11 D.M., 10 HLP, 4 HOT, 7 HTN); no data regarding concurrent infections during the one-year period | 101 individuals; mean age 35–71 y.o.; 74 M, 27 F; 55 smokers; 80 SCZ; 19 SCA; 1 BD; 1 DD; (not applicable) |

| [25] | Case report | 22,000; (18,200) | 12 weeks | Not applicable | Not applicable | 51 y.o. M; SCA; (not applicable) |

| [26] | Case series | First case: up to a maximum of 14,600 (10,500); second case: 19,400 (not available) | First case: starting from 45th week through to 59th week;second case: over an 18-month follow-up | Lithium in both cases | Not applicable | Two M individuals; 30 y.o. and 56 y.o.; two SCA; (not applicable) |

| [27] | Case report | 99% of leukocyte counts in a three-year period were >11,000; (not applicable) | Three years | Fluoxetine, Clonazepam, Disulfiram, Esomeprazole, Clomipramine | No relevant comorbidity was found despite a broad medical evaluation | 37 y.o.; M; SCZ |

| [28] | Case series | >11,000 (available only for 2/7 cases, >7800) | Two to eight years | Clonazepam, Olanzapine, Quetiapine, Valproic Acid (3/7 on clozapine monotherapy) | BPH; CAD; CHF; DM; GERD; HLP; HTN; HON; SD | Seven M individuals, all smokers; age range 42–52 y.o.; six SCZ, one of those with M.R. comorbidity; one SCA; (not available) |

| [29] | Retrospective cohort study | 15,000–21,000; among 2404 included patients, 185 individuals presented leukocytosis, with a 7% incidence | Four years | Not available | Not available | 1515 M; 889 F; SCZ; (no significant impact of the leukocytosis on the medical or psychiatric prognosis; it resolved spontaneously in all patients) |

| [30] | Case report | Intermittent leukocytosis from the 15th through the 24th week of treatment up to 15,000 (not available) | 23 weeks | Atenolol | Head injury; HTN; splenectomy | 50 y.o. M; SCZ; non-smoker; (not applicable) |

| [31] | Retrospective chart review study | >11,000 | Transient (only in one case it lasted for two years) | No differences in blood dyscrasia incidence were found between clozapine monotherapy vs. polypharmacy | 68 individuals; 28.9 y.o. among males; 34.2 y.o. among females; 43% developed neutrophilia; one individual presented chronic leukocytosis; (not applicable) | |

| [32] | Case report | Observed after 44 weeks of treatment through week 54 and up to a maximum of 16,000 (>7800) | 54-week follow-up | Benzodiazepines, Amitriptyline | Mild pharyngeal irritation with slight swollen cervical glands; despite a broad medical evaluation, no relevant comorbidity was found | 55 y.o. M; smoker; PDM; (worsening depressive symptoms) |

| Case #, Sex, Age | Leukocytes and Neutrophils Range (Units/mm3) | Pharmacotherapy (Clozapine Dose mg/day) | Psychiatric Diagnosis, and Medical/Psychiatric Comorbidity | Clozapine and Norclozapine Plasma Levels (ng/mL) | Clozapine/Norclozapine Ratio | Follow-Up Duration (years) | Smoking Status (Cigarettes/Day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, M, 47 | 11,000–15,000; | Clozapine (400), lithium | SCA, MID | 404, 313 | 1.29 | 6 | 10 |

| 2, M, 44 | 9900–16,000; 6100–12,000 | Clozapine (400), atenolol, atorvastatin, alprazolam | SCZ, COPD, DMT 2 | 475, 329 | 1.44 | 7 | 20 |

| 3, M, 47 | 11,800–14,600; 5300–7900 | Clozapine (300), oxcarbazepine, biperiden, promazine, delorazepam, clonazepam | SCA, HCV, SUD | 580, 480 | 1.2 | 3 | 20 |

| 4, F, 37 | 7600–21,600; 5600–17,600 | Clozapine (225), levothyroxine, gabapentin, aripiprazole, delorazepam, lorazepam | SCA | 451, 380 | 1.18 | 4 | 40 |

| 5, M, 47 | 7500–20,450; 5200–20,450 | Clozapine (175), paliperidone, escitalopram, delorazepam, lamotrigine | SCA, CD, BTT | 109, 69.4 | 1.57 | 1 | 20 |

| 6, M, 57 | 5500–14,800; 2800–11,700 | Clozapine (225), gabapentin, phenobarbital, biperiden, risperidone, clonazepam | SCZ, MID | 290, 223 | 1.3 | 3 | None |

| 7, F, 49 | 10,500–13,300 | Clozapine (350), lithium | SCA, ATT | 443, 348 | 1.27 | 10 | None |

| 8, M, 51 | 10,500–24,000; 6700–18,000 | Clozapine (600), zuclopenthixol, haloperidol, flurazepam, gabapentin, choline | SCZ | 353, 108 | 3.2 | 5 | 15 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paribello, P.; Manchia, M.; Zedda, M.; Pinna, F.; Carpiniello, B. Leukocytosis Associated with Clozapine Treatment: A Case Series and Systematic Review of the Literature. Medicina 2021, 57, 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57080816

Paribello P, Manchia M, Zedda M, Pinna F, Carpiniello B. Leukocytosis Associated with Clozapine Treatment: A Case Series and Systematic Review of the Literature. Medicina. 2021; 57(8):816. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57080816

Chicago/Turabian StyleParibello, Pasquale, Mirko Manchia, Massimo Zedda, Federica Pinna, and Bernardo Carpiniello. 2021. "Leukocytosis Associated with Clozapine Treatment: A Case Series and Systematic Review of the Literature" Medicina 57, no. 8: 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57080816

APA StyleParibello, P., Manchia, M., Zedda, M., Pinna, F., & Carpiniello, B. (2021). Leukocytosis Associated with Clozapine Treatment: A Case Series and Systematic Review of the Literature. Medicina, 57(8), 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57080816