Relationship between Precarious Employment and Unmet Dental Care Needs among Korean Workers: A Longitudinal Panel Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

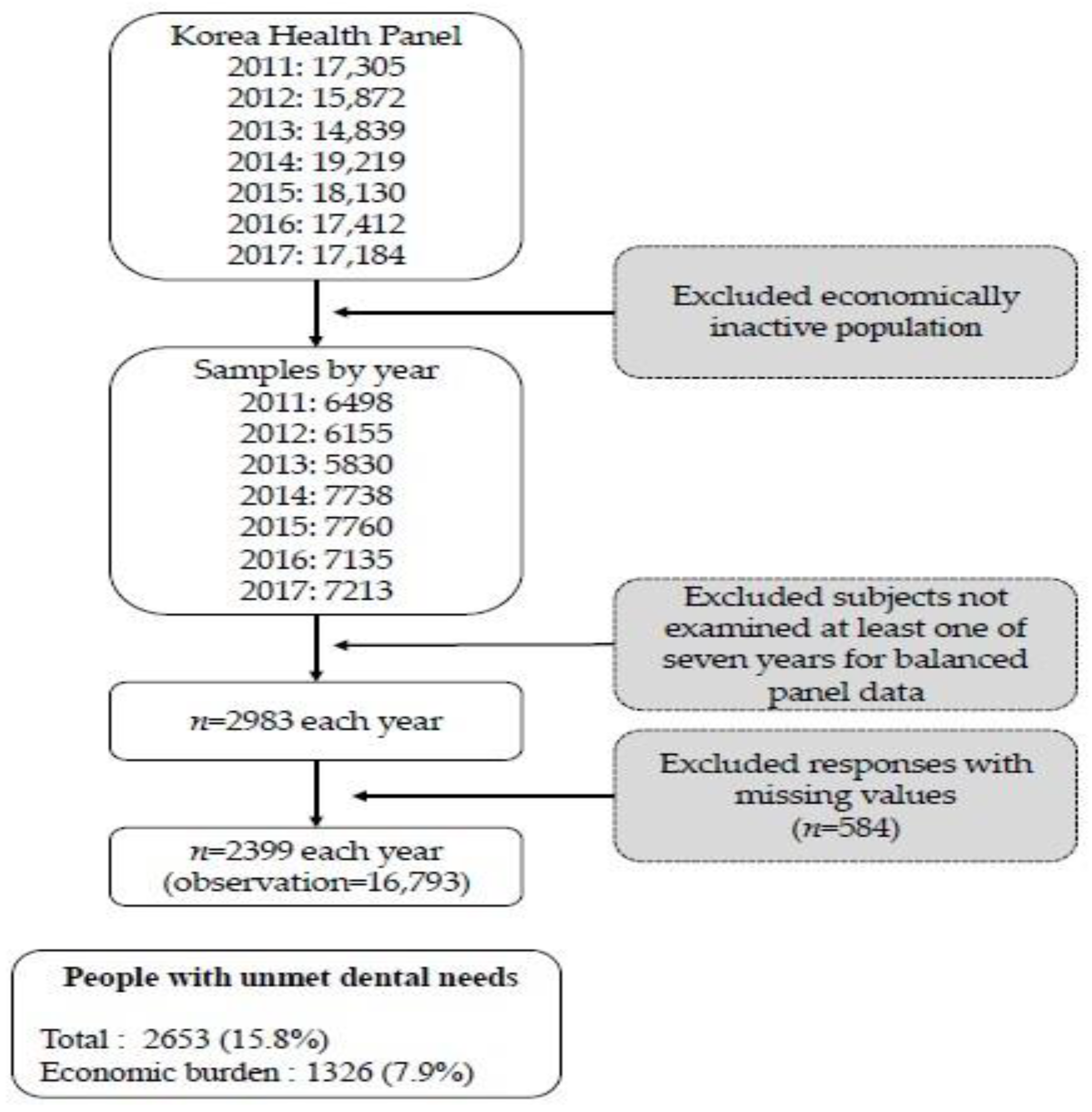

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Independent Variable

2.2.2. Dependent Variable

2.2.3. Covariates

2.2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

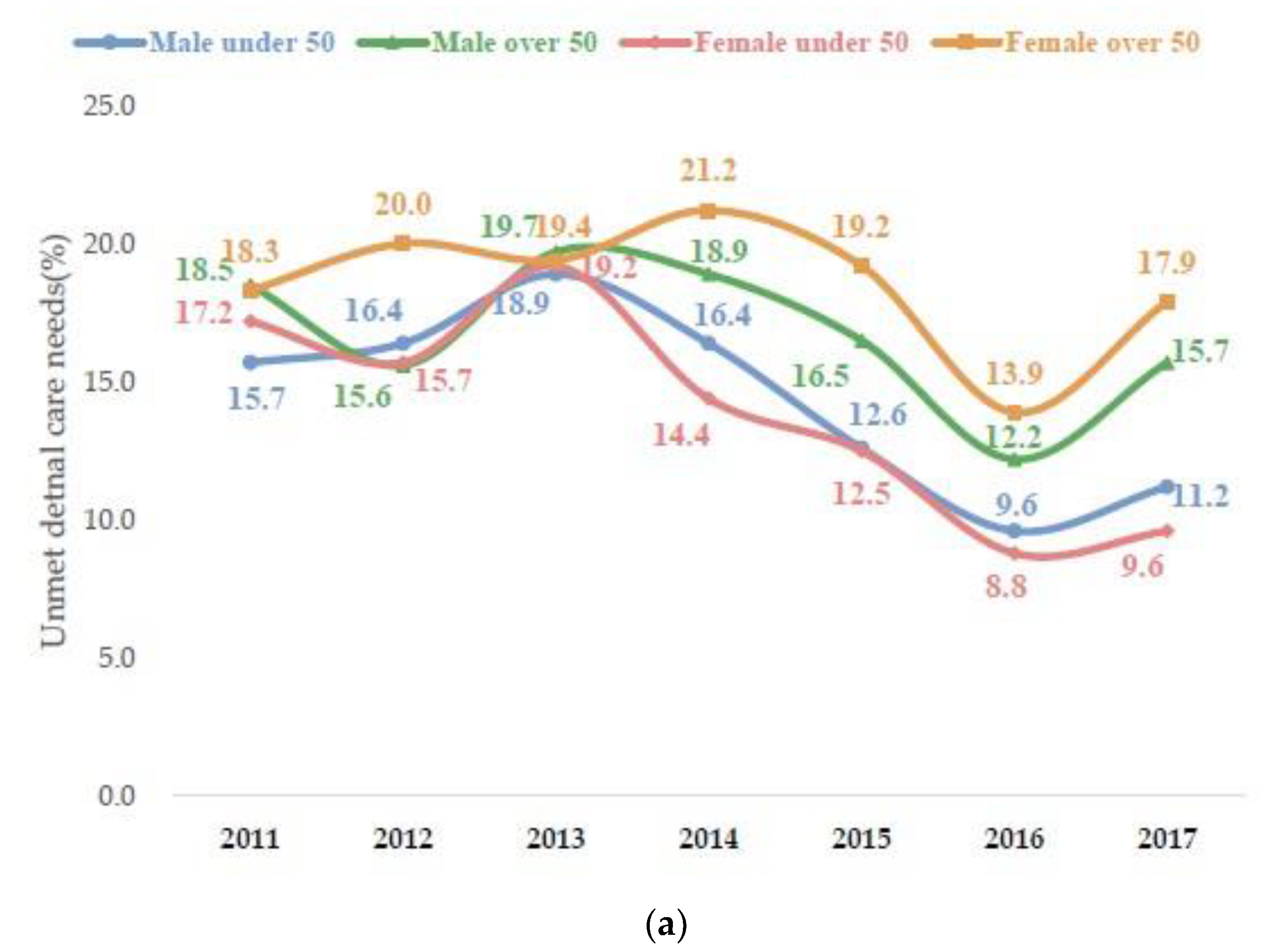

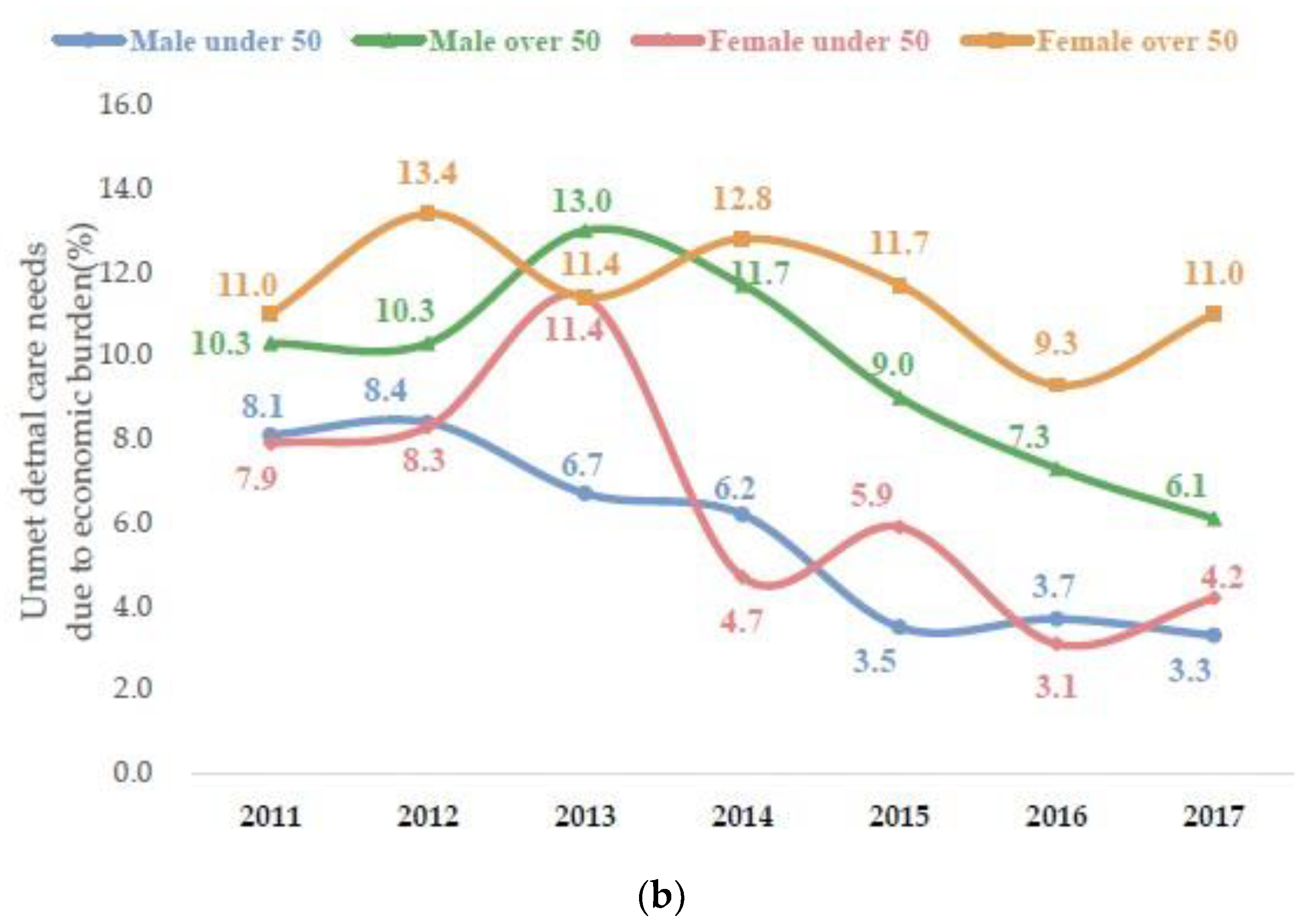

3.2. Unmet Dental Care Needs Based on Socioeconomic Characteristics

3.3. Unmet Dental Care Needs by Precarious Employment According to Gender and Age

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Julià, M.; Vanroelen, C.; Bosmans, K.; Van Aerden, K.; Benach, J. Precarious employment and quality of employment in relation to health and well-being in Europe. Int. J. Health Serv. 2017, 47, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadden, W.C.; Muntaner, C.; Benach, J.; Gimeno, D.; Benavides, F.G. A glossary for the social epidemiology of work organization: Part 3, terms from the sociology of labor markets. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S. The neoliberal economic restructuring and the change of labor market in South Korea: Paradox of flexibility. Korean J. Sociol. 2002, 36, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, C.W.; Kang, J.H.; Seo, N.K. Unmet healthcare needs depending on employment status. Health Policy 2015, 119, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Temporary Employment Data 2021. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/emp/temporary-employment.htm (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Bodin, T.; Çağlayan, Ç.; Garde, A.H.; Gnesi, M.; Jonsson, J.; Kiran, S.; Kreshpaj, B.; Leinonen, T.; Mehlum, I.S.; Nena, E.; et al. Precarious employment in occupational health—An OMEGA-NET working group position paper. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2020, 46, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.H.; Kim, C.Y.; Park, J.K.; Kawachi, I. Is precarious employment damaging to self-rated health? Results of propensity score matching methods, using longitudinal data in South Korea. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 1982–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreshpaj, B.; Orellana, C.; Burström, B.; Davis, L.; Hemmingsson, T.; Johansson, G.; Kjellberg, K.; Jonsson, J.; Wegman, D.H.; Bodin, T. What is precarious employment? A systematic review of definitions and operationalizations from quantitative and qualitative studies. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2020, 46, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.Y.; Park, S.G.; Hwang, S.H.; Min, K.B. Disparities in precarious workers’ healthcare access in South Korea. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2016, 59, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntaner, C.; Borrell, C.; Vanroelen, C.; Chung, H.; Benach, J.; Kim, I.H.; Ng, E. Employment relations, social class and health: A review and analysis of conceptual and measurement alternatives. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 2130–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benach, J.; Muntaner, C. Precarious employment and health: Developing a research agenda. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 276–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsbergis, P.A.; Grzywacz, J.G.; LaMontagne, A.D. Work organization, job insecurity, and occupational health disparities. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2014, 57, 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.; Holmes, A.M.; Blackburn, J. Prevalence of and factors associated with unmet dental need among the US adult population in 2016. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2021, 49, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.E.; Kim, N.H.; Jang, T.W.; Kawachi, I. Impact of long working hours and shift work on perceived unmet dental need: A panel study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, M.; Che, X.; Park, H.J. Unmet dental care needs among Korean national health insurance beneficiaries based on income inequalities: Results from five waves of a population-based panel study. Healthcare 2020, 8, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.W.; Choi, Y.; Lee, T.H.; Lee, H.J.; Ju, Y.J.; Park, E.C. Employment status and unmet dental care needs in South Korea: A population-based panel study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e022436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.H.; Lee, T. The decision of old-aged workers on labor market re-entry and re-employment. Korean J. Labor. Econ. 2022, 45, 71–108. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.J.; Choi, S.J. An analysis of the progressive retirement process of middle-aged men: Focusing on the period of retirement and job stability. J. Vocat. Educ. Res. 2021, 40, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Park, H.J. The relationship between precarious work and unmet dental care needs in South Korea: Focus on job and income insecurity. J. Korean Acad. Oral. Health 2018, 42, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Sohn, M.; Park, H.J. Unmet dental care needs in South Korea: How do they differ by insurance system? J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2019, 24, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lee, J.H.; Park, S.; Kim, T.I. Changes in dental care access upon healthcare benefit expansion to include scaling. J. Periodontal. Implant. Sci. 2016, 46, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarzadegan, A.; Mittinty, M.; Brennan, D.S.; Jamieson, L.M. Income-based inequalities in dental service utilization: A multiple mediation analysis. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2022. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.; Cho, H.A.; Kim, B.R. Dental expenditure by household income in Korea over the period 2008–2017: A review of the national dental insurance reform. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.J. Analysis of career interrupted female baby boomer’s return to the workforces. Soc. Welf. Policy. 2017, 44, 105–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Sohn, M.; Kim, J.; Moon, D.; Yoo, S.R.; Jung, H.W. The study of Seoul paid sick leave for precarious workers and innovative healthcare policy. Seoul. Health Found. 2018, 106–129. Available online: http://www.seoulhealth.kr (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Chung, E.; Han, G.H.; Ha, J. The sense of mastery as a moderator and mediator of the impact of job insecurity on the health of Korean baby boomers. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2015, 35, 355–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. What kind of support can sick workers get from their employers? A study on social protections for sickness in US. Switzerland and Israel. Korea Soc. Policy Rev. 2019, 26, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.H.; Khang, Y.H.; Jung-Choi, K.; Lim, S. Association between shift work and periodontal health in a representative sample of an Asian population. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2013, 39, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, O.J.; Kim, I.J. Comparison of dental treatment needs of workers depending on their working patterns. J. Korean Soc. Dent. Hyg. 2019, 19, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, K.T. Path to poverty of sick workers and fictional Korean social security. Korea Soc. Policy Rev. 2017, 24, 113–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S. The difference in healthcare utilization between self-employed and wage-and-salary workers: Focusing on the opportunity cost of time. Korean Econ. Rev. 2020, 68, 119–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Park, E.C.; Jang, S.I. Long working hours are associated with unmet dental needs in South Korean male adults who have experienced dental pain. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, Y.; Nagata, T.; Nagata, M.; Harada, A.; Oya, R.; Mori, K. Association between overtime work hours and preventive dental visits among Japanese workers. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Paid Workers | Self-Employed | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Job insecurity | (1) Employment contract | Temporary workers or daily employee | Self-employed with less than 4 employees and unpaid family workers |

| Non-fixed-term temporary contract workers | |||

| Fixed-term contract workers | |||

| (2) Working hours | Part-time worker | ||

| (3) Employment relation | Indirect employment, Special employment | ||

| Income insecurity | Income | Annual income less than two-thirds of the median income of all workers | |

| Group | Example | ||

| Job and income security | Group A | e.g., permanent workers | |

| Job security with income insecurity | Group B | e.g., workers involved in cleaning, facility management, security, parking management, call centers, and public sectors | |

| Job insecurity with income security | Group C | e.g., temporary or daily wage workers in construction sites, freelance professionals, and courier workers | |

| Job and income insecurity | Group D | e.g., housekeepers, learning tutors, small-scale self-employed individuals with no or less than four employees | |

| Male | Female | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 10,808 | 100.0 | 5985 | 100.0 | 16,793 | 100.0 | |

| Group | Group A | 4253 | 39.4 | 1659 | 27.7 | 5912 | 35.2 |

| Group B | 126 | 1.2 | 472 | 7.9 | 598 | 3.6 | |

| Group C | 4320 | 40.0 | 1560 | 26.1 | 5880 | 35.0 | |

| Group D | 2109 | 19.5 | 2294 | 38.3 | 4403 | 26.2 | |

| Marital status | Married | 9649 | 89.3 | 4308 | 72.0 | 13,957 | 83.2 |

| Divorced or widowed | 408 | 3.8 | 1010 | 16.9 | 1418 | 8.4 | |

| Single | 751 | 6.9 | 667 | 11.1 | 1418 | 8.4 | |

| Level of education | More than 12 years | 4190 | 38.8 | 2030 | 33.9 | 6220 | 37.0 |

| Less than 12 years | 6618 | 61.2 | 3955 | 66.1 | 10,573 | 63.0 | |

| Health Insurance status | Employee insured | 7411 | 68.6 | 4391 | 73.4 | 11,802 | 70.2 |

| Self-employed insured | 3338 | 30.9 | 1528 | 25.5 | 4866 | 29.0 | |

| Medical aid | 59 | 0.5 | 66 | 1.1 | 125 | 0.8 | |

| Social Insurance | Yes | 4443 | 41.1 | 2715 | 45.4 | 7158 | 42.6 |

| No | 6365 | 58.9 | 3270 | 54.6 | 9635 | 57.4 | |

| Private health insurance | Yes | 8973 | 83.0 | 5423 | 90.6 | 14,396 | 85.7 |

| No | 1835 | 17.0 | 562 | 9.4 | 2397 | 14.3 | |

| Self-rated health status | Good | 5167 | 47.8 | 2651 | 44.3 | 7818 | 46.6 |

| Moderate | 4870 | 45.1 | 2737 | 45.7 | 7607 | 45.3 | |

| Poor | 771 | 7.1 | 597 | 10.0 | 1368 | 8.1 | |

| Disability | No | 10,253 | 94.9 | 5881 | 98.3 | 16,134 | 96.1 |

| Yes | 555 | 5.1 | 104 | 1.7 | 659 | 3.9 | |

| Unmet dental care needs | No | 9136 | 84.5 | 5003 | 83.6 | 14,139 | 84.2 |

| Yes | 1672 | 15.5 | 981 | 16.4 | 2653 | 15.8 | |

| Unmet dental care needs due to economic burden | No | 9136 | 84.5 | 5003 | 83.6 | 14,139 | 84.2 |

| Yes | 808 | 7.5 | 518 | 8.7 | 1326 | 7.9 | |

| 18–49 | Over 50 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | % | No | % | p-Value | Yes | % | No | % | p-Value | |||

| Male | Unmet dental care needs | Group A | 360 | 12.4 | 2479 | 87.6 | 0.001 | 181 | 13.6 | 1233 | 86.3 | <0.001 |

| Group B | 10 | 20.1 | 34 | 79.9 | 15 | 19.9 | 67 | 80.1 | ||||

| Group C | 286 | 15.8 | 1526 | 84.2 | 425 | 16.8 | 2083 | 83.2 | ||||

| Group D | 53 | 20.1 | 187 | 79.9 | 342 | 19.7 | 1527 | 80.3 | ||||

| Unmet dental care needs due to economic burden | Group A | 108 | 3.8 | 2479 | 96.2 | <0.001 | 70 | 5.6 | 1233 | 94.4 | <0.001 | |

| Group B | 6 | 11.4 | 34 | 88.6 | 14 | 19.4 | 67 | 80.6 | ||||

| Group C | 116 | 7.0 | 1526 | 93.0 | 218 | 9.3 | 2083 | 90.7 | ||||

| Group D | 33 | 13.0 | 187 | 87.0 | 243 | 14.0 | 1527 | 86.0 | ||||

| Female | Unmet dental care needs | Group A | 149 | 11.8 | 1085 | 88.2 | 0.053 | 62 | 14.8 | 362 | 85.2 | 0.055 |

| Group B | 29 | 10.8 | 234 | 89.2 | 39 | 18.0 | 170 | 82.0 | ||||

| Group C | 138 | 15.5 | 727 | 84.5 | 119 | 17.0 | 576 | 83.0 | ||||

| Group D | 119 | 15.0 | 661 | 85.0 | 326 | 20.7 | 1188 | 79.3 | ||||

| Unmet dental care needs due to economic burden | Group A | 34 | 3.0 | 1085 | 97.0 | <0.001 | 19 | 4.8 | 362 | 95.2 | <0.001 | |

| Group B | 12 | 5.1 | 234 | 94.9 | 15 | 8.0 | 170 | 92.0 | ||||

| Group C | 65 | 8.3 | 727 | 91.7 | 66 | 9.8 | 576 | 90.2 | ||||

| Group D | 79 | 10.1 | 661 | 89.9 | 228 | 15.2 | 1188 | 84.8 | ||||

| Male | Female | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–49 | Over 50 | 18–49 | Over 50 | ||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Unmet dental care needs | Group A | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Group B | 1.55 | 0.65–3.68 | 1.53 | 0.82–2.86 | 0.91 | 0.55–1.50 | 1.19 | 0.70–2.01 | |

| Group C | 1.19 | 0.93–1.52 | 1.34 | 1.04–1.72 | 1.31 | 0.93–1.82 | 0.96 | 0.64–1.44 | |

| Group D | 1.47 | 0.96–2.25 | 1.60 | 1.21–2.18 | 1.33 | 0.96–1.85 | 1.07 | 0.73–1.58 | |

| Unmet dental care needs due to economic burden | Group A | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Group B | 2.20 | 0.78–6.21 | 3.36 | 1.68–6.71 | 1.58 | 0.67–3.72 | 1.59 | 0.70–3.60 | |

| Group C | 1.74 | 1.17–2.57 | 1.51 | 1.06–2.16 | 2.40 | 1.40–4.11 | 1.59 | 0.86–2.93 | |

| Group D | 2.70 | 1.55–4.71 | 2.26 | 1.54–3.30 | 3.04 | 1.80–5.12 | 2.07 | 1.15–3.74 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Che, X.; Sohn, M.; Moon, S.; Park, H.-J. Relationship between Precarious Employment and Unmet Dental Care Needs among Korean Workers: A Longitudinal Panel Study. Medicina 2022, 58, 1547. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58111547

Che X, Sohn M, Moon S, Park H-J. Relationship between Precarious Employment and Unmet Dental Care Needs among Korean Workers: A Longitudinal Panel Study. Medicina. 2022; 58(11):1547. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58111547

Chicago/Turabian StyleChe, Xianhua, Minsung Sohn, Sungje Moon, and Hee-Jung Park. 2022. "Relationship between Precarious Employment and Unmet Dental Care Needs among Korean Workers: A Longitudinal Panel Study" Medicina 58, no. 11: 1547. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58111547

APA StyleChe, X., Sohn, M., Moon, S., & Park, H.-J. (2022). Relationship between Precarious Employment and Unmet Dental Care Needs among Korean Workers: A Longitudinal Panel Study. Medicina, 58(11), 1547. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58111547