Assessing the Level of Knowledge and Experience Regarding Cervical Cancer Prevention and Screening among Roma Women in Romania

Abstract

:1. Introduction

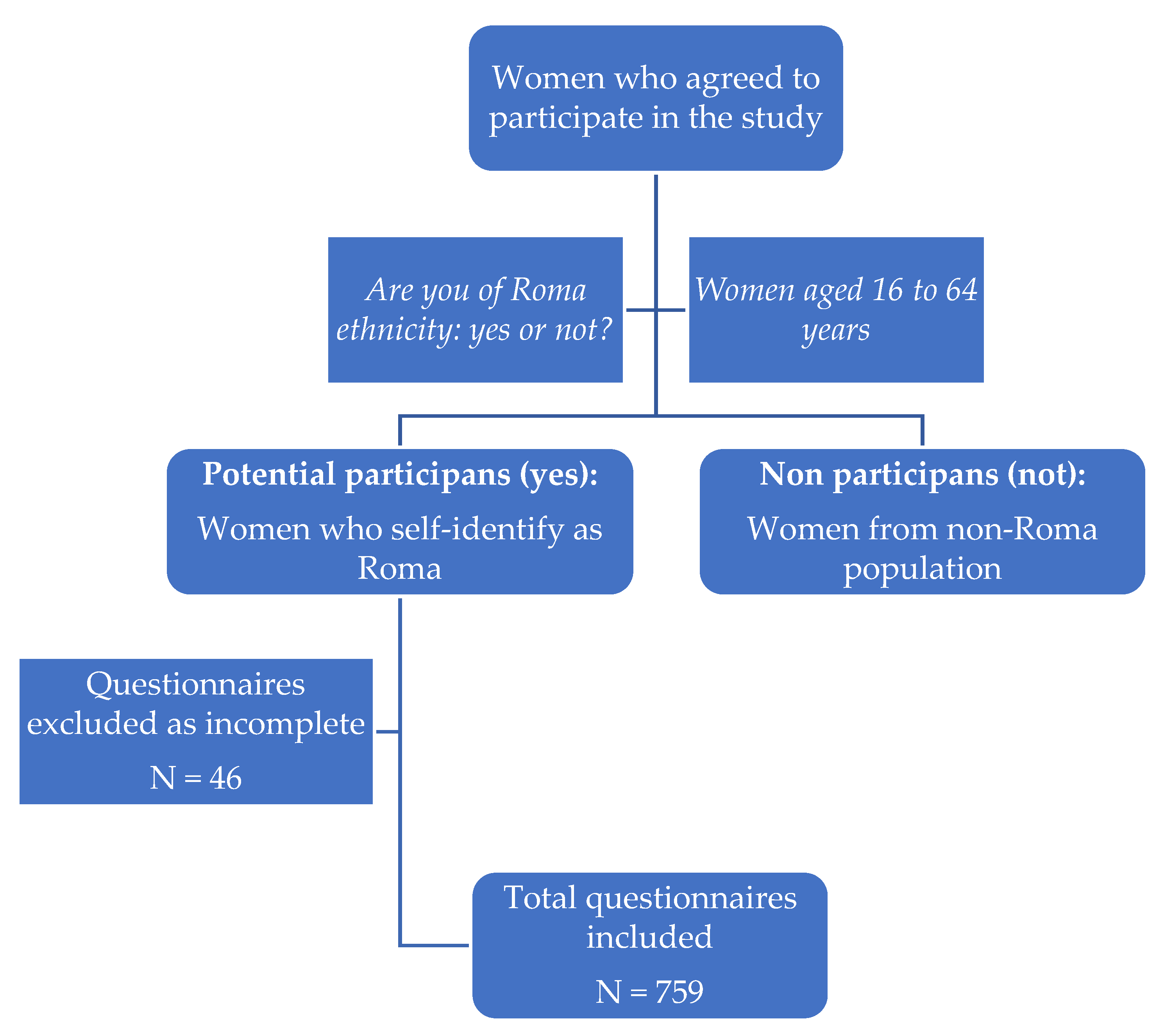

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Group

3.2. Features of the Group According to Sexual Life

3.3. Information about CC, Prevention

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, L.; Albero, G.; Serrano, B.; Abbott, M.; Collado, J.; Gómez, D.; Muñoz, J.; Bosch, F.; de Sanjosé, S. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in the World. Summary Report 10 March 2023. Available online: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/XEX.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Voidăzan, T.S.; Budianu, M.A.; Rozsnyai, F.F.; Kovacs, Z.; Uzun, C.C.; Neagu, N. Assessing the Level of Knowledge, Beliefs and Acceptance of HPV Vaccine: A Cross-Sectional Study in Romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monitorul Oficial Al României Hotărâre Pentru Aprobarea Strategiei Guvernului României de Incluziune a Cetātenilor Români Apartinând Minoritatii Rome Pentru Perioada 2015–2020. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-01/2021_chp_romania_romanian.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- OECD; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Romania. Profilul Sănătății În 2021; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombat, K.; van Dijk, J.P. Roma Health: An Overview of Communicable Diseases in Eastern and Central Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institutul Naţional de Statistică Comunicat de Presă. Recensământul Populației Și Locuințelor, Runda 2021—Date Provizorii În Profil Teritorial. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/com_presa/com_pdf/rpl2021_date_provizorii_profil_teritorial_ian_2023.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Hajioff, S.; McKee, M. The Health of the Roma People: A Review of the Published Literature. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2000, 54, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicula, F.A.; Suteu, O.; Pais, R.; Neamtiu, L. Description of the national situation of cervical cancer screening in the member states of the European Union. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 2685–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultekin, M.; Ramirez, P.T.; Broutet, N.; Hutubessy, R. World Health Organization Call for Action to Eliminate Cervical Cancer Globally. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 426–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Assembly Adopts Global Strategy to Accelerate Cervical Cancer Elimination. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/19-08-2020-world-health-assembly-adopts-global-strategy-to-accelerate-cervical-cancer-elimination (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Nyanchoka, L.; Damian, A.; Nygård, M. Understanding Facilitators and Barriers to Follow-up after Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Examination among Women Living in Remote Areas of Romania: A Qualitative Study Protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e053954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotărârea Privind Aprobarea Programelor Naţionale de Sănătate. Available online: https://ms.ro/ro/centrul-de-presa/hot%C4%83r%C3%A2rea-privind-aprobarea-programelor-na%C5%A3ionale-de-s%C4%83n%C4%83tate/ (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Andreassen, T.; Melnic, A.; Figueiredo, R.; Moen, K.; Şuteu, O.; Nicula, F.; Ursin, G.; Weiderpass, E. Attendance to Cervical Cancer Screening among Roma and Non-Roma Women Living in North-Western Region of Romania. Int. J. Public Health 2018, 63, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, T.; Weiderpass, E.; Nicula, F.; Suteu, O.; Itu, A.; Bumbu, M.; Tincu, A.; Ursin, G.; Moen, K. Controversies about Cervical Cancer Screening: A Qualitative Study of Roma Women’s (Non)Participation in Cervical Cancer Screening in Romania. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 183, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, L.; Rotaru, V.; Cirimbei, C.; Gales, L.; Stefan, D.-C.; Ionescu, S.-O.; Luca, D.; Doran, H.; Chitoran, E. Inequities in Screening and HPV Vaccination Programs and Their Impact on Cervical Cancer Statistics in Romania. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambrea, S.C.; Aschie, M.; Resul, G.; Mitroi, A.F.; Chisoi, A.; Nicolau, A.A.; Baltatescu, G.I.; Cretu, A.M.; Lupasteanu, G.; Serbanescu, L.; et al. HPV and HIV Coinfection in Women from a Southeast Region of Romania-PICOPIV Study. Medicina 2022, 58, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iova, C.F.; Badau, D.; Daina, M.D.; Șuteu, C.L.; Daina, L.G. Evaluation of the Knowledge and Attitude of Adolescents Regarding the HPV Infection, HPV Vaccination and Cervical Cancer in a Region from the Northwest of Romania. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2023, 17, 2249–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtunescu, F.; Bohiltea, R.E.; Neacsu, A.; Grigoriu, C.; Pop, C.S.; Bacalbasa, N.; Ducu, I.; Iordache, A.-M.; Costea, R.V. Cervical Cancer Mortality in Romania: Trends, Regional and Rural–Urban Inequalities, and Policy Implications. Medicina 2022, 58, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todor, R.D.; Bratucu, G.; Moga, M.A.; Candrea, A.N.; Marceanu, L.G.; Anastasiu, C.V. Challenges in the Prevention of Cervical Cancer in Romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.; Oluboyede, Y.; Vale, L.; Olariu, E. Differences in Health-Related Quality of Life between the Roma Community and the General Population in Romania. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2022, 6, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olariu, E.; Paveliu, M.S.; Baican, E.; Oluboyede, Y.; Vale, L.; Niculescu-Aron, I.G. Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life in the General Population and Roma Communities in Romania: Study Protocol for Two Cross-Sectional Studies. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Cancer Information System. Available online: https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Wentzensen, N.; Arbyn, M. HPV-Based Cervical Cancer Screening-Facts, Fiction, and Misperceptions. Prev. Med. 2017, 98, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysostomou, A.C.; Stylianou, D.C.; Constantinidou, A.; Kostrikis, L.G. Cervical Cancer Screening Programs in Europe: The Transition Towards HPV Vaccination and Population-Based HPV Testing. Viruses 2018, 10, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidakis, D.; Moustaki, I.; Zervas, I.; Barbouni, A.; Merakou, K.; Chrysi, M.S.; Creatsa, G.; Panoskaltsis, T. Knowledge of Greek Adolescents on Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) and Vaccination. Medicine 2017, 96, e5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, B.C.; Terebessy, A.; Tóth, E.; Balázs, P. Young Hungarian Students’ Knowledge about HPV and Their Attitude Toward HPV Vaccination. Vaccines 2016, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.; Costello, L.; Murphy, J.; Prendiville, W.; Martin, C.M.; O’Leary, J.J.; Sharp, L.; Irish Screening Research Consortium (CERVIVA). “I Don’t Care Whether It’s HPV or ABC, I Just Want to Know If I Have Cancer”. Factors Influencing Women’s Emotional Responses to Undergoing Human Papillomavirus Testing in Routine Management in Cervical Screening: A Qualitative Study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 121, 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowakowski, A.; Cybulski, M.; Śliwczyński, A.; Chil, A.; Teter, Z.; Seroczyński, P.; Arbyn, M.; Anttila, A. The Implementation of an Organised Cervical Screening Programme in Poland: An Analysis of the Adherence to European Guidelines. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.R.; Silva, S.; Moura-Ferreira, P.; Villaverde-Cabral, M.; Santos, O.; do Carmo, I.; Barros, H.; Lunet, N. Cancer Screening in Portugal: Sex Differences in Prevalence, Awareness of Organized Programmes and Perception of Benefits and Adverse Effects. Health Expect. 2017, 20, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigore, M.; Popovici, R.; Pristavu, A.; Grigore, A.M.; Matei, M.; Gafitanu, D. Perception and Use of Pap Smear Screening among Rural and Urban Women in Romania. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 1084–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigore, M.; Teleman, S.I.; Pristavu, A.; Matei, M. Awareness and Knowledge About HPV and HPV Vaccine Among Romanian Women. J. Cancer Educ. 2018, 33, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oz, M.; Cetinkaya, N.; Apaydin, A.; Korkmaz, E.; Bas, S.; Ozgu, E.; Gungor, T. Awareness and Knowledge Levels of Turkish College Students about Human Papilloma Virus Infection and Vaccine Acceptance. J. Cancer Educ. 2018, 33, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanidou, C.; Dimopoulos, K. Greek Health Professionals’ Perceptions of the HPV Vaccine, State Policy Recommendations and Their Own Role with Regards to Communication of Relevant Health Information. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorsters, A.; Bonanni, P.; Maltezou, H.C.; Yarwood, J.; Brewer, N.T.; Bosch, F.X.; Hanley, S.; Cameron, R.; Franco, E.L.; Arbyn, M.; et al. The Role of Healthcare Providers in HPV Vaccination Programs—A Meeting Report. Papillomavirus Res. 2019, 8, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Guideline for Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-Cancer Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240030824 (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Voidăzan, T.S.; Uzun, C.C.; Kovacs, Z.; Rosznayai, F.F.; Turdean, S.G.; Budianu, M.-A. The Hybrid Capture 2 Results in Correlation with the Pap Test, Sexual Behavior, and Characteristics of Romanian Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekalegn, Y.; Sahiledengle, B.; Woldeyohannes, D.; Atlaw, D.; Degno, S.; Desta, F.; Bekele, K.; Aseffa, T.; Gezahegn, H.; Kene, C. High Parity Is Associated with Increased Risk of Cervical Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Womens Health 2022, 18, 17455065221075904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, C. Sexual Behaviour and Sexual and Reproductive Health Education: A Cross-Sectional Study in Romania. Reprod. Health 2014, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilisiu, M.B.; Hashim, D.; Andreassen, T.; Støer, N.C.; Nicula, F.; Weiderpass, E. HPV Testing for Cervical Cancer in Romania: High-Risk HPV Prevalence among Ethnic Subpopulations and Regions. Ann. Glob. Health 2019, 85, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorova, I.L.G.; Baban, A.; Balabanova, D.; Panayotova, Y.; Bradley, J. Providers’ Constructions of the Role of Women in Cervical Cancer Screening in Bulgaria and Romania. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Have You Ever Been Tested for HPV? | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 Yes (289) | Group 2 No (470) | |||

| What age group are you in? | <18 years | 7 (2.4) | 129 (27.4) | 0.0001 |

| 19–24 years | 53 (18.3) | 73 (15.5) | ||

| 25–34 years | 75 (26.0) | 171 (36.4) | ||

| 35–44 years | 73 (25.3) | 43 (9.1) | ||

| 45–54 years | 60 (20.8) | 39 (8.3) | ||

| 55–64 years | 21 (7.3) | 15 (3.2) | ||

| Origin | Rural | 154 (53.3) | 359 (76.4) | 0.0001 |

| Education | No schooling | 29 (10) | 84 (17.9) | 0.0001 |

| Secondary education | 98 (33.9) | 306 (65.1) | ||

| High school education | 148 (51.2) | 80 (17.0) | ||

| Undergraduate education | 14 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 202 (69.9) | 183 (38.9) | 0.0001 |

| Unmarried | 66 (22.8) | 279 (59.4) | ||

| Divorced | 14 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Widow | 7 (2.4) | 8 (1.7) | ||

| How many cigarettes do you smoke on average per day? | Under 5/day | 28 (9.7) | 43 (9.1) | 0.0001 |

| 5–10/day | 21 (7.3) | 91 (19.4) | ||

| 11–20/day | 54 (18.7) | 82 (17.4) | ||

| Over 20/day | 18 (6.2) | 8 (1.7) | ||

| I do not smoke | 168 (58.1) | 246 (52.3) | ||

| Do you use alcohol? | 1–2 times a week | 53 (18.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0001 |

| I do not use alcohol at all | 236 (81.7) | 470 (100) | ||

| Which of the following eating habits do you employ? | Exclusively meat products | 0 (0.0) | 36 (7.7) | 0.0001 |

| Exclusively vegetables | 0 (0.0) | 14 (3) | ||

| Mixed diet | 289 (100) | 420 (89.4) | ||

| Variables | Have You Ever Been Tested for HPV? | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 Yes (289) | Group 2 No (470) | |||

| At what age did you start your sexual life? | under 18 | 184 (63.7) | 388 (82.6) | 0.0001 |

| over 18 | 105 (36.3) | 61 (13) | ||

| I have not started my sex life | 0 (0.0) | 21 (4.5) | ||

| What is the number of your sexual partners? | 1 | 150 (51.9) | 236 (50.2) | 0.001 |

| 2–5 | 118 (40.8) | 184 (39.1) | ||

| Over 5 | 21 (7.3) | 29 (6.2) | ||

| None | 0 (0.0) | 21 (4.5) | ||

| What is the frequency of vaginal sex? | Under 3/week | 261 (90.3) | 373 (79.4) | 0.001 |

| Over 3/week | 28 (9.7) | 76 (16.1) | ||

| I have not started my sex life | 0 (0.0) | 21 (4.5) | ||

| How many pregnancies have you had? | 1 | 37 (12.8) | 83 (17.7) | 0.0001 |

| 2–3 | 87 (30.1) | 144 (30.6) | ||

| 4–5 | 25 (8.7) | 141 (30) | ||

| Over 5 | 105 (36.3) | 74 (15.7) | ||

| None | 35 (12.1) | 28 (6) | ||

| Of the total number of pregnancies, how many miscarriages have you had? | 1 | 40 (15.7) | 80 (18.1) | 0.0001 |

| 2–3 | 50 (19.7) | 48 (10.9) | ||

| Over 3 | 55 (21.6) | 33 (7.5) | ||

| None | 109 (42.9) | 281 (63.5) | ||

| What contraceptive methods do you use? | Contraceptive barriers | 11 (3.8) | 21 (4.5) | 0.0001 |

| Coitus interruptus | 7 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Hormonal contraceptives | 93 (32.2) | 62 (13.2) | ||

| Intrauterine devices | 33 (11.4) | 14 (3) | ||

| Calendar method | 42 (14.5) | 7 (1.5) | ||

| I do not know of/use any contraceptive method | 103 (35.7) | 300 (63.8) | ||

| Sterilization | 0 (0.0) | 66 (14) | ||

| Variables | Have You Ever Been Tested for HPV? | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 Yes (289) | Group 2 No (470) | |||

| Are you registered with a general practitioner? | Yes | 289 (100) | 448 (95.3) | 0.01 |

| No | 0 (0.0) | 22 (4.7) | ||

| Have you ever had a CC diagnosis? | Yes | 25 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0001 |

| No | 264 (91.3) | 470 (100) | ||

| Is there anyone in your family with a CC diagnosis? | Yes | 50 (17.3) | 50 (10.6) | 0.008 |

| No | 239 (82.7) | 420 (89.4) | ||

| Do you have any family members with other types of cancer? | Yes | 82 (28.4) | 64 (13.6) | 0.0001 |

| No | 207 (71.6) | 406 (86.4) | ||

| Have you ever undergone gynecological examinations? | Yes | 289 (100) | 387 (82.3) | 0.0001 |

| No | 0 (0.0) | 83 (17.7) | ||

| If so, how long ago? | Within the last year | 218 (75.4) | 257 (54.7) | 0.0001 |

| Within the last 2 years | 21 (7.3) | 50 (10.6) | ||

| Within the last 5 years | 50 (17.3) | 80 (17) | ||

| Never | 0 (0.0) | 83 (17.7) | ||

| Have you ever heard of HPV? | Yes | 182 (63.0) | 140 (28.8) | 0.0001 |

| No | 107 (37.0) | 330 (70.2) | ||

| Have you been vaccinated against HPV? | Yes, with at least one dose | 47 (16.2) | 91 (19.3) | 0.002 |

| Yes, with 2–3 doses | 57 (19.7) | 48 (10.2) | ||

| No | 185 (64.1) | 331 (70.5) | ||

| Have you ever had a cervico-vaginal cytological examination? | Yes | 282 (97.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0001 |

| No | 7 (2.4) | 470 (100) | ||

| Following the Pap test, what types of cervical intraepithelial lesions were found? | Cancerous cells | 11 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0001 |

| HSIL type cells | 7 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| LSIL type cells | 7 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Inflammatory cells | 21 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Normal cells | 201 (69.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| I do not know | 35 (12.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| No such testing | 7 (2.4) | 470 (100) | ||

| If you have undergone treatment, was the lesion treated? | Yes | 56 (19.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0001 |

| No | 18 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| No treatment | 215 (74.4) | 470 (100) | ||

| Have you ever had a genital tract infection? | Yes | 181 (62.6) | 264 (56.2) | 0.079 |

| No | 108 (37.4) | 206 (43.8) | ||

| If so, what infection did you have? | Candidiasis | 63 (21.8) | 43 (9.2) | 0.0001 |

| HPV | 28 (9.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Urinary infection | 146 (50.5) | 250 (53.2) | ||

| Vaginitis | 7 (2.4) | 7 (1.5) | ||

| No infection | 108 (37.4) | 206 (43.8) | ||

| Have you ever had surgery for gynecological diseases? | Yes | 85 (29.4) | 107 (22.8) | 0.048 |

| No | 204 (70.6) | 363 (77.2) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Voidăzan, S.; Budianu, A.M.; Francisc, R.F.; Kovacs, Z.; Uzun, C.C.; Apostol, B.E.; Bodea, R. Assessing the Level of Knowledge and Experience Regarding Cervical Cancer Prevention and Screening among Roma Women in Romania. Medicina 2023, 59, 1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59101885

Voidăzan S, Budianu AM, Francisc RF, Kovacs Z, Uzun CC, Apostol BE, Bodea R. Assessing the Level of Knowledge and Experience Regarding Cervical Cancer Prevention and Screening among Roma Women in Romania. Medicina. 2023; 59(10):1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59101885

Chicago/Turabian StyleVoidăzan, Septimiu, Alexandra Mihaela Budianu, Rozsnyai Florin Francisc, Zsolt Kovacs, Cosmina Cristina Uzun, Bianca Elena Apostol, and Reka Bodea. 2023. "Assessing the Level of Knowledge and Experience Regarding Cervical Cancer Prevention and Screening among Roma Women in Romania" Medicina 59, no. 10: 1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59101885