Palliative Care and End-of-Life Issues in Patients with Brain Cancer Admitted to ICU

Abstract

1. Introduction

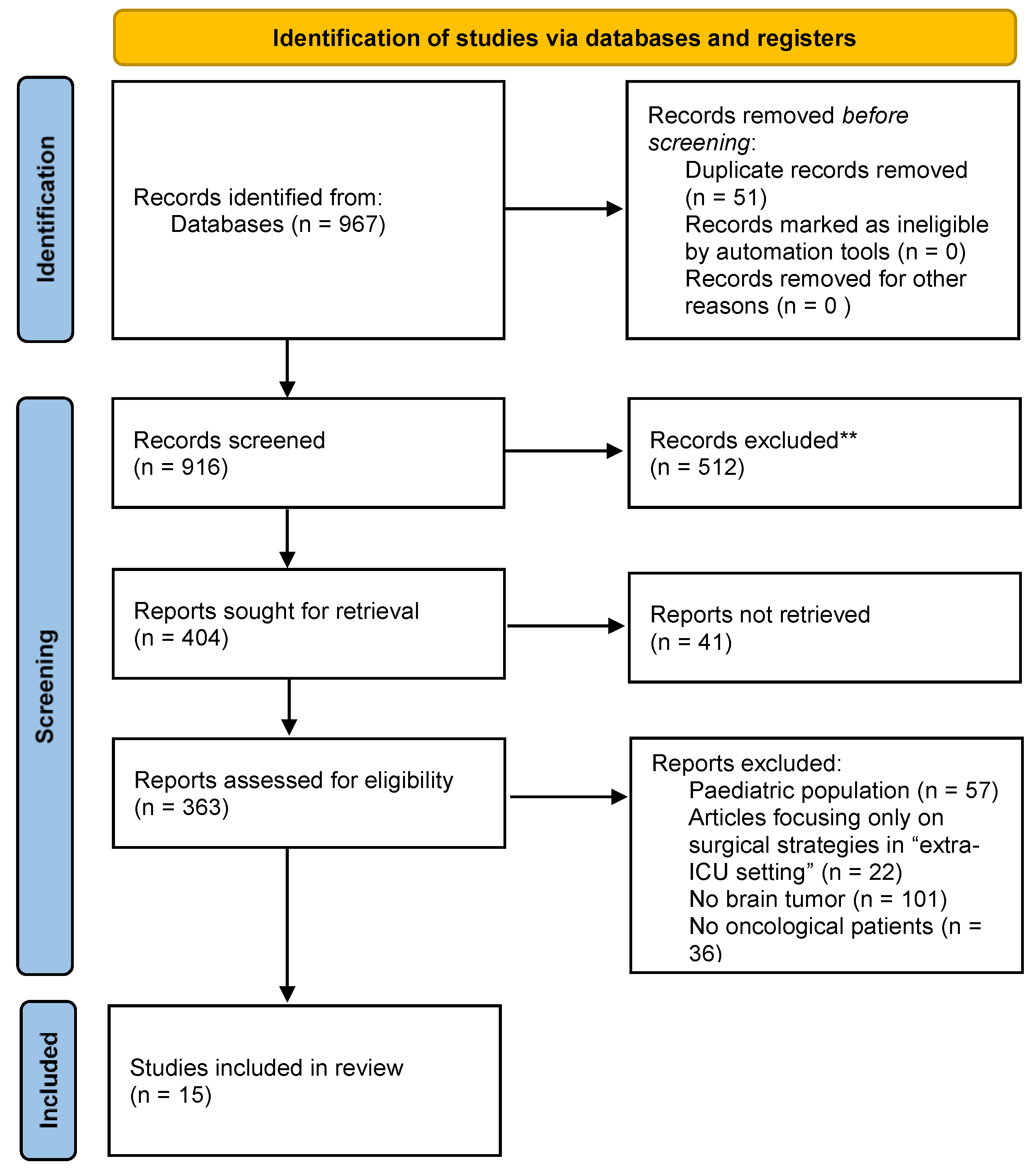

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Selection

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Full Article in English;

- Clinical studies (case series, observational cohort studies, retrospective or prospective studies);

- Patients age ≥18;

- Patients affected by primary or secondary brain tumors;

- Studies focusing on palliative/supportive care in ICU setting;

- Studies assessing patients, caregivers, or medical staffs’ perspective about end-of-life (EoL) period.

- Exclusion criteria:

- Articles not in English;

- Editorials, literature reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses;

- Patients age ≥18;

- Oncological patients without brain involvement;

- Studies considering neurosurgical palliative treatments in oncological patients;

- Studies not assessing palliative or supportive care;

- Studies evaluating palliative care in an “extra-ICU” setting.

2.3. Data Collection and Presentation

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Setting Goals of Care in Neuro-Oncology

4.2. When and How to Palliative Care Consult

4.3. Palliative Care Approaches

4.4. Clinicians Point of View and Potential Issues

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giammalva, G.R.; Iacopino, D.G.; Azzarello, G.; Gaggiotti, C.; Graziano, F.; Gulì, C.; Pino, M.A.; Maugeri, R. End-of-Life Care in High-Grade Glioma Patients. The Palliative and Supportive Perspective. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ippolito, M.; Giarratano, A.; Cortegiani, A. Healthcare-Associated Central Nervous System Infections. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2022, 35, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalisano, G.; Ippolito, M.; Marino, C.; Giarratano, A.; Cortegiani, A. Palliative Care Principles and Anesthesiology Clinical Practice: Current Perspectives. J. Multidiscip. Health 2021, 14, 2719–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walbert, T. Palliative Care, End-of-Life Care, and Advance Care Planning in Neuro-Oncology. CONTINUUM Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 2017, 23, 1709–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climans, S.A.; Mason, W.P.; Variath, C.; Edelstein, K.; Bell, J.A.H. Neuro-Oncology Clinicians’ Attitudes and Perspectives on Medical Assistance in Dying. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 48, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, R.A.; Ou, A.; Naqvi, S.M.A.A.; Naqvi, S.M.; Weathers, S.P.S.; O’Brien, B.J.; De Groot, J.F.; Bruera, E. Aggressiveness of Care at End of Life in Patients with High-Grade Glioma. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 8387–8394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.; Mroz, E.L.; Popescu, C.; Baron-Lee, J.; Busl, K.M. Palliative Care Services in the NeuroICU: Opportunities and Persisting Barriers. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2021, 38, 1342–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubendran, S.; Schockett, E.; Jackson, E.; Huynh-Le, M.P.; Roberti, F.; Rao, Y.J.; Ojong-Ntui, M.; Goyal, S. Trends in Inpatient Palliative Care Use for Primary Brain Malignancies. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 6625–6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, L.N.; Back, A.L.; Creutzfeldt, C.J. Palliative Care Consultations in the Neuro-ICU: A Qualitative Study. Neurocrit. Care 2016, 25, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroz, E.L.; Olasoji, E.; Henke, C.; Lim, C.; Pacheco, S.C.; Swords, G.; Hester, J.; Weisbrod, N.; Babi, M.A.; Busl, K.; et al. Applying the Care and Communication Bundle to Promote Palliative Care in a Neuro-Intensive Care Unit: Why and How. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, J.; Massaro, A.; Siegler, J.; Sloate, S.; Mendlik, M.; Stein, S.; Levine, J. Palliative Care in Patients with High-Grade Gliomas in the Neurological Intensive Care Unit. Neurohospitalist 2020, 10, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creutzfeldt, C.J.; Engelberg, R.A.; Healey, L.; Cheever, C.S.; Becker, K.J.; Holloway, R.G.; Curtis, J.R. Palliative Care Needs in the Neuro-Icu. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Iwamoto, F.M.; Kreisl, T.N.; Welch, M.R.; Odia, Y.; Donovan, L.E.; Joanta-Gomez, A.E.; Evans, K.A.; Lassman, A.B. Causes of Death and End-of-Life Care in Patients with Intracranial High-Grade Gliomas: A Retrospective Observational Study. Neurology 2022, 98, E260–E266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, L.E.; Polacek, L.C.; Panageas, K.; Reiner, A.; Walbert, T.; Thomas, A.A.; Buthorn, J.; Sigler, A.; Prigerson, H.G.; Applebaum, A.J.; et al. Coping with Glioblastoma: Prognostic Communication and Prognostic Understanding among Patients with Recurrent Glioblastoma, Caregivers, and Oncologists. J. Neurooncol. 2022, 158, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumble, K.; Driessen, A.; Borgstrom, E.; Martin, J.; Yardley, S.; Cohn, S. How Much Information Is ‘Reasonable’? A Qualitative Interview Study of the Prescribing Practices of Palliative Care Professionals. Palliat. Med. 2022, 36, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, T.H.; Wiley, J.F.; Holmboe, E.S.; Tseng, C.H.; Vespa, P.; Kleerup, E.C.; Wenger, N.S. Differences between Attendings’ and Fellows’ Perceptions of Futile Treatment in the Intensive Care Unit at One Academic Health Center: Implications for Training. Acad. Med. 2015, 90, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, A.; Wu, S.P.; Gorovets, D.; Sansosti, A.; Kryger, M.; Beaudreault, C.; Chung, W.Y.; Shelton, G.; Silverman, J.; Lowy, J.; et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Brain Metastases Decreases Inpatient Admissions and Need for Imaging Studies. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2018, 35, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottash, M.; McCamey, D.; Groninger, H.; Aulisi, E.F.; Chang, J.J. Palliative Care Consultation and Effect on Length of Stay in a Tertiary-Level Neurological Intensive Care Unit. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2020, 1, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.H.; Price, M.; Dalton, T.; Ramirez, L.; Fecci, P.E.; Kamal, A.H.; Johnson, M.O.; Peters, K.B.; Goodwin, C.R. Palliative Care Use for Critically Ill Patients with Brain Metastases. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlon, A.; Murphy, M. Medical Futility in the Care of Non-Competent Terminally Ill Patient: Nursing Perspectives and Responsibilities. Aust. Crit. Care 2014, 27, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thier, K.; Calabek, B.; Tinchon, A.; Grisold, W.; Oberndorfer, S. The Last 10 Days of Patients with Glioblastoma: Assessment of Clinical Signs and Symptoms as Well as Treatment. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2016, 33, 985–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontera, J.A.; Curtis, J.R.; Nelson, J.E.; Campbell, M.; Gabriel, M.; Mosenthal, A.C.; Mulkerin, C.; Puntillo, K.A.; Ray, D.E.; Bassett, R.; et al. Integrating Palliative Care into the Care of Neurocritically Ill Patients. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 1964–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, D.; Yen, Y.F.; Hu, H.Y.; Lai, Y.J.; Sun, W.J.; Ko, M.C.; Huang, L.Y.; Chen, C.C.; Randall Curtis, J.; Lee, Y.L.; et al. Factors Associated with Advance Directives Completion among Patients with Advance Care Planning Communication in Taipei, Taiwan. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegier, P.; Varenbut, J.; Bernstein, M.; Lawlor, P.G.; Isenberg, S.R. “No Thanks, I Don’t Want to See Snakes Again”: A Qualitative Study of Pain Management versus Preservation of Cognition in Palliative Care Patients. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotzé, C.; Roos, J.L. Ageism, Human Rights and Ethical Aspects of End-of-Life Care for Older People with Serious Mental Illness. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 906873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnik, S.; Kanekar, A. Ethical Issues Surrounding End-of-Life Care: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2016, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, E.E.; Furlong, B. Health Care Ethics, 3rd ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Sudbury, MA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-44966-535-7. [Google Scholar]

- Thorns, A. Ethical and Legal Issues in End-of-Life Care. Clin. Med. J. R. Coll. Physicians Lond. 2010, 10, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Kukora, S.K.; Arslanian-Engoren, C.; Deldin, P.J.; Pituch, K.; Frank Yates, J. Aiding End-of-Life Medical Decision-Making: A Cardinal Issue Perspective. Palliat. Support. Care 2020, 18, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boersma, I.; Miyasaki, J.; Kutner, J.; Kluger, B. Palliative Care and Neurology: Time for a Paradigm Shift. Neurology 2014, 83, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, B.R.; Twaddle, M.L.; Melnick, A.; Meier, D.E. National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care Guidelines, 4th Edition. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 1684–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluck, S.; Mroz, E.L.; Baron-Lee, J. Providers’ Perspectives on Palliative Care in a Neuromedicine-Intensive Care Unit: End-of-Life Expertise and Barriers to Referral. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedenberg, A.S.; Levy, M.M.; Ross, S.; Evans, L.E. Barriers to End-of-Life Care in the Intensive Care Unit: Perceptions Vary by Level of Training, Discipline, and Institution. J. Palliat. Med. 2012, 15, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paladino, J.; Bernacki, R.; Neville, B.A.; Kavanagh, J.; Miranda, S.P.; Palmor, M.; Lakin, J.; Desai, M.; Lamas, D.; Sanders, J.J.; et al. Evaluating an Intervention to Improve Communication between Oncology Clinicians and Patients with Life-Limiting Cancer: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial of the Serious Illness Care Program. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Design | Population | Goals | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climans et al. [6] | Survey, single-center. | A total of 125 healthcare professionals involved in neuro-oncology. | To explore attitudes towards medical assistance in death (MAiD), interpretation of scenarios. | Questions on nine scenarios of brain cancer patients needing medical assistance in death. |

| Harrison et al. [7] | Observational retrospective study, single-center. | A total of 212 patients identified, including 80 HGG patients without PCC, 52 HGG patients with PCC and 80 non-CNS-primary cancer with PCC. | To evaluate end-of-life score, assessing aggressiveness of EoL care in the cohorts of included patients. | Aggressiveness of EoL care score; time to PC referral. |

| Morris et al. [8] | Observational retrospective study, single-center. | A total of 330 patients expired in neuro-ICU from both neurology and neurosurgery services. | To identify barriers, institutional or patient-related, to the provision of palliative care service. | Time to palliative care referral and arrival, time to hospice referral and arrival, time to withdrawal of curative care, time to expiration and thematic barriers to referral. |

| Kubendran et al. [9] | Observational retrospective multicentric study. | A total of 37,365 patients with primary brain malignancies in inpatient palliative care consult in a 10-year period. | To identify factors involved in inpatients’ palliative care in patients with PBMs. | Rates and risk factors for palliative care consultation over the study period. |

| Tran et al. [10] | Retrospective observational qualitative study, single-center. | A total of 25 neuro-ICU patients who underwent a PCC during their ICU stay. | To perform content analysis on the palliative care note and to identify main differences between patients with and those without PCC. | Reasons and issues addressed in PC consultations. |

| Mroz et al. [11] | Retrospective observational cohort study, single-center. | A total of 133 critically ill neurology and neurosurgery patients expired in a 2-year period in NICU. | To analyze the application of care and communication bundle in the ICU. | Barriers to care and communication bundles in the neuro-ICU. |

| Rosenberg et al. [12] | Retrospective observational cohort study, single-center. | A total of 90 patients with diagnosed HGG admitted to a neuro-ICU | To assess the incidence rate of an inpatient PCC, association between PCC and DNR status, length of stay, discharge dispositions, death within 30 days of admission, death location and 30-day readmission rate. | Incidence of inpatient palliative care consultation, code status amendment to do not resuscitate (DNR), discharge disposition, 30-day mortality and 30-day readmission rate, length of stay and place of death. |

| Creutzfeldt et al. [13] | Quality improvement project with a prospective parallel group cohort study, single-center. | A total of 130 patients from a neuro-ICU with implemented palliative care needs screening; a total of 132 patients from a neuro-ICU without implemented PC needs screening. | To identify palliative care needs for patients and their families and potential ways to meet those needs. | Prevalence and nature of palliative care needs and actions to address those needs through the use of four questions. |

| Barbaro et al. [14] | Retrospective observational cohort study, single-center. | A total of 132 adults with intracranial high-grade gliomas. | To understand patterns of care and circumstances surrounding end of life in patients with intracranial gliomas. | Causes and location of death, comfort measures and resuscitation effort. |

| Walsh et al. [15] | Prospective multicentric study. | A total of 17 patient, caregiver, and oncologist triads were analyzed. | To examine communication processes and goals among patients, caregivers and oncologists to elucidate drivers of prognostic understanding in the context of recurrent GBM. | Concordance between patient, caregiver and oncologist communication processes and goals. |

| Dumble et al. [16] | Prospective multicentric qualitative study. | A total of 10 prescribing clinicians (doctors and nurses). | To explore some of the many factors prescribing clinicians in the UK considered when deciding what information to give to EoL patients about medication choices and when. | Thematic factors. |

| Neville et al. [17] | Single-center retrospective comparative cohort study. | A total of 36 attendings and 14 fellows in intensive care units. | To explore prognostic ability among critical care fellows, comparing fellows’ and attendings’ assessments of futile critical care, and evaluate factors associated with assessments. | Frequency of futile treatment assessments and reasons |

| Habibi et al. [18] | Single-center retrospective observational cohort study. | A total of 145 patients diagnosed with brain metastases, including inpatients and admitted to ICU. | To study the effect of timing of palliative care (early vs. late) encounters on brain metastasis patients. | Palliative encounter, patient outcomes and healthcare utilization. |

| Pottash et al. [19] | Single-center retrospective observational cohort study. | A total of 55 patients admitted to the neurological ICU receiving a palliative care consultation. | To investigate the characteristics and impact of palliative care consultation for patients under the management of neurosurgical and critical care services. | Length of stay and mortality. |

| Kang et al. [20] | Single-center retrospective cohort analysis. | A total of 118 brain metastatic patients admitted to an intensive care unit. | To compare who received an inpatient palliative care consult with those who did not. | Mortality, time from intensive care unit admission to death, disposition and change in code status. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frisella, S.; Bonosi, L.; Ippolito, M.; Giammalva, G.R.; Ferini, G.; Viola, A.; Marchese, V.A.; Umana, G.E.; Iacopino, D.G.; Giarratano, A.; et al. Palliative Care and End-of-Life Issues in Patients with Brain Cancer Admitted to ICU. Medicina 2023, 59, 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59020288

Frisella S, Bonosi L, Ippolito M, Giammalva GR, Ferini G, Viola A, Marchese VA, Umana GE, Iacopino DG, Giarratano A, et al. Palliative Care and End-of-Life Issues in Patients with Brain Cancer Admitted to ICU. Medicina. 2023; 59(2):288. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59020288

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrisella, Sara, Lapo Bonosi, Mariachiara Ippolito, Giuseppe Roberto Giammalva, Gianluca Ferini, Anna Viola, Valentina Anna Marchese, Giuseppe Emmanuele Umana, Domenico Gerardo Iacopino, Antonino Giarratano, and et al. 2023. "Palliative Care and End-of-Life Issues in Patients with Brain Cancer Admitted to ICU" Medicina 59, no. 2: 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59020288

APA StyleFrisella, S., Bonosi, L., Ippolito, M., Giammalva, G. R., Ferini, G., Viola, A., Marchese, V. A., Umana, G. E., Iacopino, D. G., Giarratano, A., Cortegiani, A., & Maugeri, R. (2023). Palliative Care and End-of-Life Issues in Patients with Brain Cancer Admitted to ICU. Medicina, 59(2), 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59020288