Unexpected Tension Pneumothorax after Double-Lumen Endotracheal Intubation in Patients with Pulmonary Edema: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

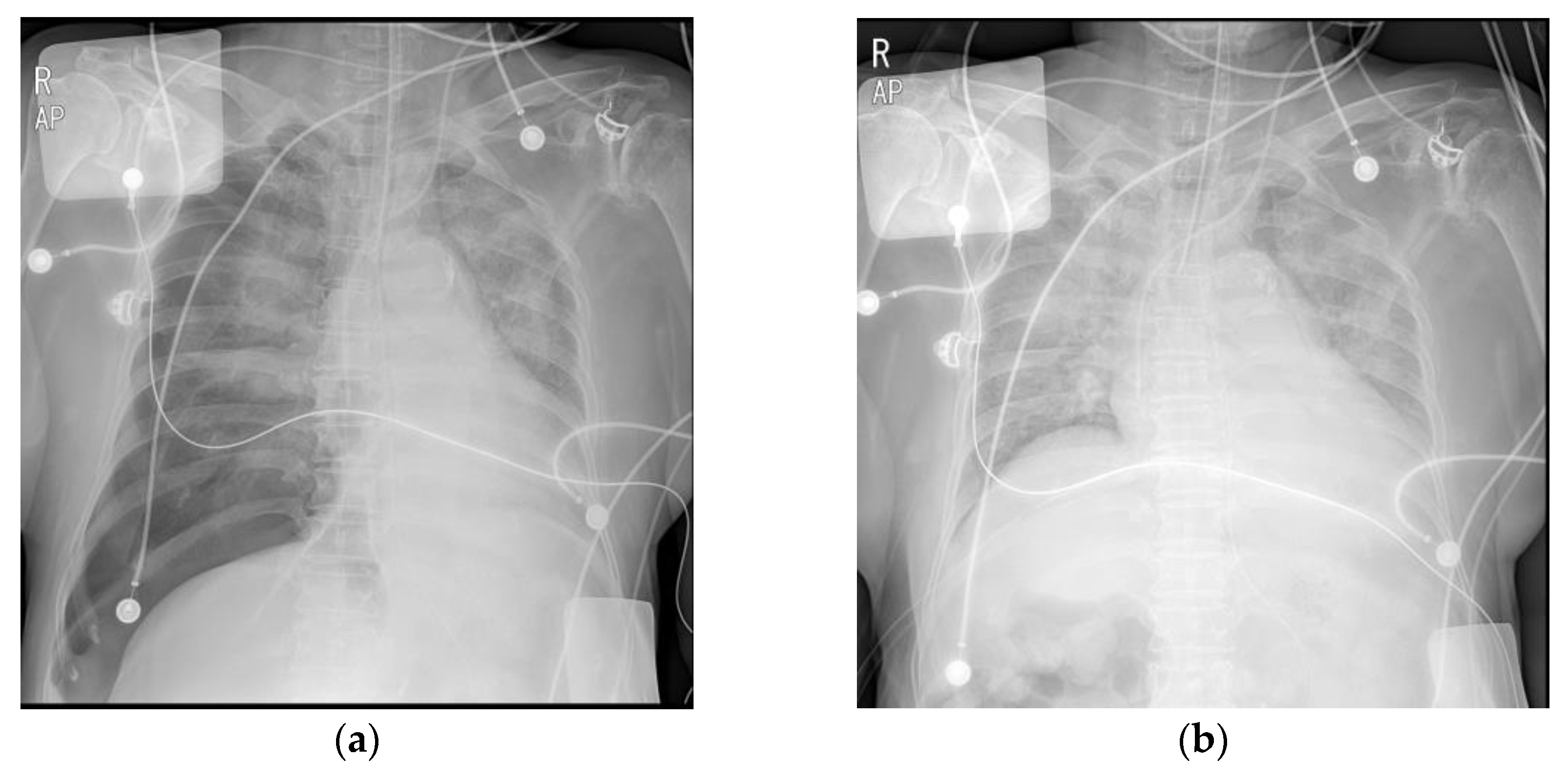

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hsu, C.W.; Sun, S.F. Iatrogenic pneumothorax related to mechanical ventilation. World J. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.; Falk, G.L. Surgical tension pneumothorax during laparoscopic repair of massive hiatus hernia: A different situation requiring different management. Anaesth. Intensiv. Care 2011, 39, 1120–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parienti, J.J.; Mongardon, N.; Mégarbane, B.; Mira, J.P.; Kalfon, P.; Gros, A.; Marqué, S.; Thuong, M.; Pottier, V.; Ramakers, M.; et al. Intravascular complications of central venous catheterization by insertion site. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaniti, E.; Provitsaki, C.; Papakonstantinou, P.; Tagarakis, G.; Sapalidis, K.; Dalakakis, I.; Gkinas, D.; Grosomanidis, V. Unexpected tension pneumothorax-hemothorax during induction of general anaesthesia. Case Rep. Anesthesiol. 2019, 2019, 5017082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheney, F.W.; Posner, K.L.; Caplan, R.A. Adverse respiratory events infrequently leading to malpractice suits. A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 1991, 75, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Jahr, J.S.; Sullivan, E.; Waters, P.F. Tracheobronchial rupture after double-lumen endotracheal intubation. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2004, 18, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.C.; Chou, A.H.; Liu, H.P.; Ho, C.Y.; Yun, M.W. Tension pneumothorax complicated by double-lumen endotracheal tube intubation. Chang Gung Med. J. 2005, 28, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brodsky, J.B.; Macario, A.; Mark, J.B. Tracheal diameter predicts double-lumen tube size: A method for selecting left double-lumen tubes. Anesth. Analg. 1996, 82, 861–864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bahk, J.H.; Oh, Y.S. Prediction of double-lumen tracheal tube depth. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 1999, 13, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussarsar, M.; Thierry, G.; Jaber, S.; Roudot-Thoraval, F.; Lemaire, F.; Brochard, L. Relationship between ventilatory settings and barotrauma in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensiv. Care Med. 2002, 28, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, R.M. The use of an endotracheal ventilation catheter in the management of difficult extubations. Can. J. Anaesth. 1996, 43, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggan, L.V.; Law, J.A.; Murphy, M.F. Brief review: Supplementing oxygen through an airway exchange catheter: Efficacy, complications, and recommendations. Can. J. Anaesth. 2011, 58, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benumof, J.L. Airway exchange catheters: Simple concept, potentially great danger. Anesthesiology 1999, 91, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherng, C.H.; Wong, C.S.; Hsu, C.H.; Ho, S.T. Airway length in adults: Estimation of the optimal endotracheal tube length for orotracheal intubation. Can. J. Anaesth. 2002, 14, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, J.H. Which device should be considered the best for lung isolation: Double-lumen endotracheal tube versus bronchial blockers. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2007, 20, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.C.H.; Martin, J.; Lal, A.; Diegeler, A.; Folliguet, T.A.; Nifong, L.W.; Perier, P.; Raanani, E.; Smith, J.M.; Seeburger, J.; et al. Minimally invasive versus conventional open mitral valve surgery: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Innovations (Phila) 2011, 6, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, A.; Patvardhan, C.; Falter, F. Anesthesia for minimally invasive cardiac surgery. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 1886–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carlo, C.; Settimio, U.F.; Maisano, F. Mitral valve repair versus MitraClip. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 19 (Suppl. S1), e80–e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baek, J.; Park, S.J.; Seo, M.; Choi, E.K. Unexpected Tension Pneumothorax after Double-Lumen Endotracheal Intubation in Patients with Pulmonary Edema: A Case Report. Medicina 2023, 59, 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030460

Baek J, Park SJ, Seo M, Choi EK. Unexpected Tension Pneumothorax after Double-Lumen Endotracheal Intubation in Patients with Pulmonary Edema: A Case Report. Medicina. 2023; 59(3):460. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030460

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaek, Jongyoon, Sang Jin Park, Myungjin Seo, and Eun Kyung Choi. 2023. "Unexpected Tension Pneumothorax after Double-Lumen Endotracheal Intubation in Patients with Pulmonary Edema: A Case Report" Medicina 59, no. 3: 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030460

APA StyleBaek, J., Park, S. J., Seo, M., & Choi, E. K. (2023). Unexpected Tension Pneumothorax after Double-Lumen Endotracheal Intubation in Patients with Pulmonary Edema: A Case Report. Medicina, 59(3), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030460