Abstract

Although ovarian cystic teratoma is the most common ovarian tumor, complications are quite rare. However, it is important to be recognized by the radiologist in order to avoid inaccurately diagnosing them as malignant lesions. This case report describes a 61-year-old postmenopausal woman, who presented to the emergency room with abdominal pain following a minor blunt abdominal trauma. In this context, a CT scan was performed, which showed the presence of round, hypodense masses randomly distributed in the peritoneum, with coexisting ascites in moderate amount; ovarian carcinoma with peritoneal carcinomatosis was suspected. The patient was hospitalized and an MRI of the abdomen and pelvis was recommended for a more detailed lesion characterization. Following this examination, the patient was diagnosed with mature cystic ovarian teratoma complicated by rupture. Surgery was performed, and the outcome was favorable. The cases of ruptured cystic teratomas are rare, and to our knowledge, this is the first occurrence described in literature. Special attention must be paid when confronting with such a case in medical practice, since it can easily misdiagnosed as peritoneal carcinomatosis.

1. Introduction

Ovarian teratoma is the most common benign germ cell ovarian tumor (10–20%) [1]. Generally, these lesions are classified in three categories based on the constitutive elements: the first category holds tumors that have layers of detritus/cellular debris, the second characteristically presents a nodular or palm-shaped protrusion, and the last is represented by a fat-fluid level. Over the years, several cases of cystic ovarian teratomas that do not fit into the categories described above have been described, along with the presence of numerous intracystic floating balls, predominantly of fatty consistency. Mature cystic ovarian teratoma can be easily diagnosed with the help of ultrasonography, CT or MRI in situations without complications. The main drawbacks that can occur in the evolution of these lesions are represented by: ovarian torsion (the most common), rupture (1–4%), malignant transformation (1–2%), superinfection, auto-immune hemolytic anemia, hyperthyroidism (more frequently seen in ovarian goiter), carcinoid syndrome or others [1]. Following literature research, this is, to our knowledge, the first case of ruptured mature cystic ovarian teratoma with the presence of floating fatty balls.

2. Materials and Methods

This case report describes a ruptured mature cystic ovarian teratoma with the presence of floating fatty balls. For diagnosis and treatment computer tomography (CT) evaluation, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and surgery were performed. The CT scan was performed using a Somatom Definition Egde 128 slice scanner( Siemnes, Erlangen, Germany); both pre- and postcontrast scans were done. As for MRI evaluation, it was realized using a 1.5 T MRI scanner (Magnetom Aera, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany); this case also required pre- and post contrast sequences, including, DWI and chemical shift imaging sequences. The surgical treatment included laparatomy with left adnexectomy, peritoneal lavage and lysis of entero-enteric adhesions. A written consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

3. Case Presentation

We present the case of a 61-year-old female patient, who has been postmenopausal for about 10 years and referred to the emergency department after a minor abdominal trauma. The patient experienced diffuse abdominal pain which worsened over time. The initial blood count was unremarkable (Table 1).

Table 1.

Complete blood count. This table displays various laboratory tests along with their conventional units, observed values, and reference range values.

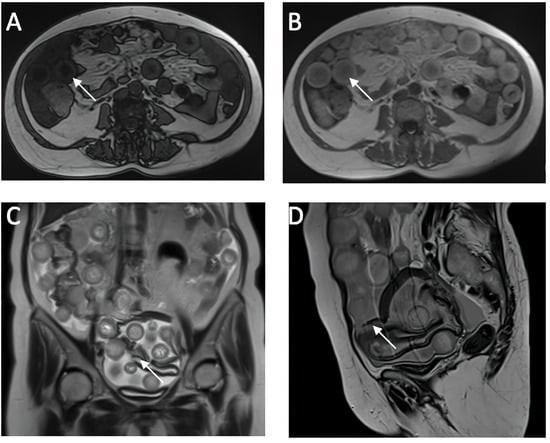

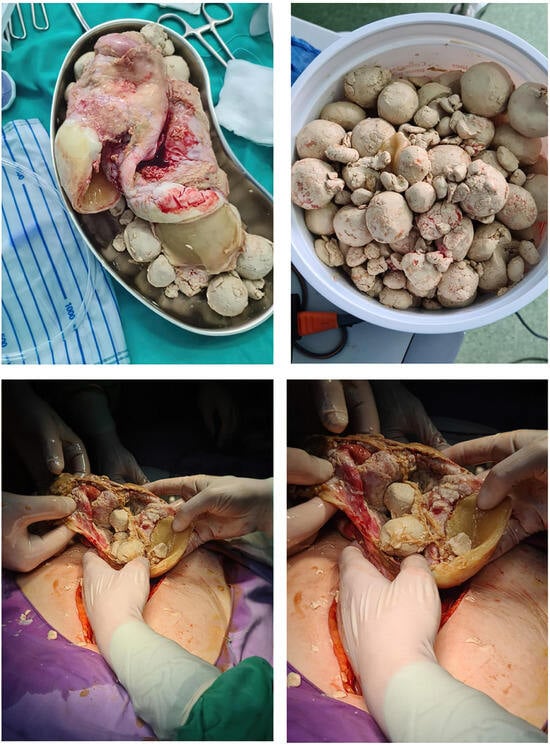

A CT investigation of the abdomen and pelvis was requested and performed. Radiology noted the presence of ascites in moderate amount, together with numerous round nodular lesions of varying sizes (between 1.5–4 cm), with no contrast uptake; the lesions were randomly distributed, with a slight prevalence for the pelvic region. However, a serpiginous lesion with intense contrast uptake was observed within the left ovary (Figure 1), leading the radiologist to falsely raise the suspicion of ovarian carcinoma with peritoneal carcinomatosis. The patient was hospitalized for additional investigations and medical treatment. After several days, an abdominal and pelvic MRI was also performed (Figure 2). Several ‘floating round bodies’ were observed throughout the whole peritoneum; the ‘floating bodies’ showed signal drop on the out-of-phase sequences suggesting fatty components. When analyzing the pelvic images, a ruptured cyst was observed across the right ovary. The diagnosis of ruptured ovarian teratoma was made and the patient underwent surgery. Left adnexectomy with peritoneal lavage and lysis of entero-enteric adhesions was performed. During the laparotomy, the peritoneal cavity was opened revealing a moderate amount of peritoneal fluid. A sample was then collected for cytologic examination. Macroscopically, the uterus had a normal appearance, with unremarkable right adnexa and left fallopian tube. As for the left ovary, a cystic mass with ruptured wall was observed. The cyst contained multiple well defined round lesions with fatty content, some of which were disseminated throughout the peritoneal cavity. To manage postoperative fluid accumulation and monitor for any complications, an abdominal drain was kept in place for 3 days after surgery. The surgical findings are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic CT Imaging of Abdominal and Pelvic Regions. (A) ascites (B) multiple round intra-peritoneal fatty density lesions without contrast uptake; (C,D) serpiginous structure with intense contrast uptake at the level of the left ovary.

Figure 2.

Cross-Sectional MRI Analysis of Abdominal and Pelvic Organs. (A,B) in-phase and op-phase images showing signal dropout on the op phase, suggesting fat content of the sphere (C,D) ruptured cyst wall which is hypointense on the T2w sequence.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative Depiction of Ruptured Ovarian Cyst with ’Floating Balls’ Phenomenon: Surgical Exploration and Findings.

Eight days after the surgical intervention, the results of the histopathological examination of the left ovary and peritoneal lavage samples were communicated, leading to the definitive diagnosis: mature cystic ovarian teratoma consisting of various tissues, including epidermal tissue with keratotic squamous epithelium, sebaceous and sweat glands, cartilaginous tissue, brain tissue, connective tissue covered with a cylindrical ciliated epithelium, muscle tissue, and adipose tissue. Additionally, there was an associated chronic non-specific granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells, with no signs of malignant proliferation. The postoperative evolution was favourable - the patient was discharged with a good general condition. Four months after the surgery, the patient returned to the obstetrics-gynecology clinic for evaluation, and no abnormalities were observed.

4. Discussion

Mature cystic ovarian teratoma, the most prevalent benign ovarian neoplasm in young, fertile women, often remains asymptomatic and unilateral (85–90%). Our case involved an incidental discovery of a left adnexal lesion following minor trauma. While typically asymptomatic, teratomas may cause pelvic pain if complicated by torsion or when significantly enlarged. Histologically, these tumors are distinguished by their composition, containing elements from at least two of the three germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. Unlike dermoid cysts, which primarily exhibit ectodermal structures, teratomas feature a broader range of tissues, including fat (present in 93% of cases), mature skin, sebaceous glands, hair follicles, sebum bags, and even complex structures like blood vessels, bone fragments, teeth, nails, eyes, cartilage, or thyroid tissue [1]. In relation to the last element, there is a subtype of ovarian teratoma called struma ovarii which is composed entirely or almost entirely of thyroid tissue [2]. In our case, the histopathological examination confirmed the following: epidermal tissue with keratotic squamous epithelium, sebaceous and sweat glands, cartilaginous tissue, brain tissue, connective tissue covered with a ciliated cylindrical epithelium, muscle tissue and adipose tissue. The mature cystic ovarian teratoma can easily be diagnosed using imaging techniques, due to the intra-cystic components which can be detected by ultrasound, CT, or MRI as summarized in Table 2. This benign ovarian neoplasm is divided into three categories based on the composing elements: the first type has layers of debris/cellular remnants, the second holds a nodular protrusion or palm-like projection known as Rokitansky nodule, and the third type contains fat-fluid level. However, there is another category that does not fit into the ones previously mentioned, and is characterized by the presence of floating fatty balls inside the cyst, also known as the “floating balls” sign. This sign is considered pathognomonic for benign ovarian cystic teratomas and is quite common, contrary to expectations [3]. These intracystic spherical lesions were first described on CT by Muramatsu et al. in 1991 [4] and later in 2000 by Otigbah et al. through ultrasound [5]. On ultrasound examination, mature cystic ovarian teratoma presents as multiple hyperechogenic round structures floating in the anechoic fluid of the cyst. In some cases, it has been shown that this anechoic liquid component is more likely to be pure sebum that becomes liquid at body temperature [6]. Additionally, a study demonstrated that 3D ultrasound has more benefits for the physician, compared to 2D ultrasound. Therefore, lesions appear in 3D ultrasound as spherical, globular structures, in a larger number and some adherent to each other, characteristics similar to those described macroscopically after laparotomy [7]. Further, we will proceed to describe mature ovarian teratomas with intra-cystic spherical ‘balls’, which are present in our case. There are few reported cases of mature cystic teratomas with multiple floating spherical masses [6]. These have been found in different locations, such as the ovary, retroperitoneum [8], and mediastinum [9], all of them with different compositions based on the mentioned region. According to Kawamoto et al., the appearance of multiple floating spheres within a pelvic cystic tumor has not been described in other pelvic lesions, making it a pathognomonic element for mature cystic ovarian teratomas [10]. The presence of the floating balls sign is more common in larger teratomas with a thicker wall, as they require more space to form [3]. It is speculated that the formation of spherical masses occurs through the aggregation of sebum around a nidus, composed of small debris, desquamated material, or fine hair strands. Aggregation is also slightly facilitated by the peristalsis of the small intestine, which is in contact with the cyst wall, but it takes a long time for them to form, explaining the slow growth rate of the lesions, at approximately 1.8 mm/year [3,10]. However, there is a case described by Donnadieu et al. [11] where a pregnant patient had a follow-up ultrasound at 22 weeks of gestation, which revealed an ovarian cystic mass with spherical lesions inside that continued to increase in size up to 20 cm within a few weeks. This case was considered the first case of mature cystic ovarian teratoma with spherical lesions in pregnant women.

Table 2.

Comparison of Imaging Modalities for Ovarian Teratomas and Peritoneal Carcinomatosis.

Due to its ability to distinguish different tissue types by their densities, even in very small amounts, CT imaging has a higher sensitivity for diagnosis compared to ultrasound but is less recommended due to ionizing radiation risk. This type of ovarian teratoma exhibits distinct imaging characteristics, which include the presence of low-density spherical masses containing a mix of fat, debris, hair strands, and fluid. Calcifications or the dermoid plug formed from the cyst wall can also be observed. In the case of a ruptured cyst, these hypodense masses are randomly distributed in the abdomen and pelvis, predominantly in the pelvic area, surrounded by the leaked intracystic fluid. In case of a ruptured cyst, the literature emphasizes that the fluid distributes in antidependent pockets, and may lead to chemical peritonitis. This may affect the mesentery and thickening of the peritoneum, closely mimicking peritoneal carcinomatosis [1,35], as initially suspected in our case through the CT examination. Malignant transformation can be suggested by the enlargement of the cystic ovarian teratoma >10 cm, soft tissue plugs, and the irregular/crenelated appearance of the cyst’s wall. Although the presented teratoma was approximately 14 cm in the largest diameter, malignancy was excluded after histopathological examination. MRI is the investigation reserved for difficult-to-diagnose cases; it is extremely sensitive to fatty structures, and contrast can identify invasive solid components, making it necessary for differentiating malignant elements. It is the preferred investigation for women of childbearing age. On T1-weighted sequences, the spherical masses have a hyperintense periphery compared to the intracystic fluid, which has a hypointense center. In contrast, on T2-weighted sequences, the signal is opposed: hypointense at the periphery and hyperintense in the center. The core section consists predominantly of hair strands and soft tissues, while the main component of the globular masses is represented by fat/sebum, which appears suppressed on fat saturation sequences [7]. A characteristic sign of these lesions is the “boba sign” [36], inspired by a Taiwanese drink called bubble tea, which contains multiple tapioca pearls, having an imaging ap-pearance similar to the globular masses in mature cystic ovarian teratoma. These MRI characteristics of the globular masses were observed in our patient as well, noting that the lesions and intracystic fluid were dispersed throughout the abdomen and pelvis, indicating a complicated ruptured teratoma. In case of a suspected teratoma, the most important MRI sequence is represented by “chemical shift” imaging. Due to the fact that all spheres contain a large amount of fat, in the opposed phase images these spheres present a homogeneous signal drop-out, which makes the diagnosis straight-forward. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a ruptured cystic teratoma with ‘floating balls’ that has both CT and MRI imaging, making this case report an extremely useful teaching material.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we can highlight the fact that mature cystic ovarian teratoma is, in most cases, an asymptomatic tumor discovered incidentally. Cystic ovarian teratomas manifest in various forms, and the presence of floating balls is rare. However, what has not yet been previously reported in the literature is the situation where a mature cystic ovarian teratoma with floating globules complicates through rupture, making the diagnosis easily to be confused with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Therefore, awareness of this possibility is crucial.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C. and A.C.M.; methodology, D.C., D.M. and F.B.; software, I.I.; validation, N.M., C.A.-M.J. and I.-F.B.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, S.M.; resources, D.C.; data curation, I.I.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C. and D.M.; writing—review and editing, A.C.M. and F.B.; visualization, I.-F.B.; supervision, S.M.; project administration, D.C.; funding acquisition, A.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gaillard, F. Mature Cystic Ovarian Teratoma. Available online: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/mature-cystic-ovarian-teratoma-1?lang=us (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Weerakkody, Y. Struma Ovarii Tumor. Available online: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/struma-ovarii-tumour?lang=us (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Şahin, H.; Akdoğan, A.I.; Ayaz, D.; Karadeniz, T.; Sancı, M. Utility of the “floating ball sign” in diagnosis of ovarian cystic teratoma. Turk. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 16, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, Y.; Moriyama, N.; Takayasu, K.; Nawano, S.; Yamada, T. CT and MR imaging of cystic ovarian teratoma with intracystic fat balls. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1991, 15, 528–529. [Google Scholar]

- Otigbah, C.; Thompson, M.O.; Lowe, D.G.; Setchell, M. Mobile globules in benign cystic teratoma of the ovary. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2000, 107, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.R.; Shah, Z.; Patwardhan, V.; Hanchate, V.; Thakkar, H.; Garg, A. Ovarian cystic teratoma: Determined phenotypic response of keratocytes and uncommon intracystic floating balls appearance on sonography and computed tomography. J. Ultrasound Med. 2002, 21, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MR and Ultrasound Imaging of Floating Globules in Mature Ovarian Cystic Teratoma. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2004, 58, 130–132. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujitoh, H.; Akiyosi, S.; Takoda, S.; Katsuki, K.; Okuda, K. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic imaging. Retroperitoneal mature cystic teratoma with a fat ball. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1998, 13, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hession, P.R.; Simpson, W. Mobile fatty globules in benign cystic teratoma of the mediastinum. Br. J. Radiol. 1996, 69, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamoto, S.; Sato, K.; Matsumoto, H.; Togo, Y.; Ueda, Y.; Tanaka, J.; Heshiki, A. Multiple Mobile Spherules in Mature Cystic Teratoma of the Ovary. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2001, 176, 1455–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnadieu, A.C.; Deffieux, X.; Ray, C.L.; Mordefroid, M.; Frydman, R.; Fernandez, H. Unusual fast-growing ovarian cystic teratoma during pregnancy presenting with intracystic fat “floating balls” appearance. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 86, 1758–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.D.; Feldstein, V.A.; Lipson, S.D.; Chen, D.C.; Filly, R.A. Cystic teratomas of the ovary: Diagnostic value of sonography. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1998, 171, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovarian Teratomas: Tumor Types and Imaging Characteristics. Radiographics 2001, 21, 475–490. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Starost, M.F.; Mauda-Havakuk, M.; Mikhail, A.S.; Partanen, A.; Wood, B.J.; Karanian, J.W.; Pritchard, W.F. Ovarian teratoma in a woodchuck (Marmota monax) with hepatocellular carcinoma: Radiologic and pathologic features. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, S.A. A Hairbrained Mature Cystic Ovarian Teratoma: With Bone Marrow, Meninges, and Intraglial Hair. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2021, 29, 404–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemian Dizajmehr, S.; Mohammadi Irvanlou, M.; Mohammadi, A.; Rashidi Fakari, F. Impact of Serum CA19-9 Level in Clinico-Pathological and Radiologic Feature of Mature Cystic Teratoma: A Case Series. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Cancer Res. 2023, 8, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.Y.; Sung, D.J.; Park, B.J.; Kim, M.J.; Cho, S.B.; Kim, K.A.; Song, J.Y. Imaging Features of Growing Teratoma Syndrome Following a Malignant Ovarian Germ Cell Tumor. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2014, 38, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.D.; Navarrete, S.V.; Pena, R.J.; Leon, M.C.E. Primary ovarian carcinoid tumor arising within a mature cystic teratoma in a 32-years-old patient. Gynecol. Reprod. Endocrinol. 2018, 2, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, S.; Alcazar, J.L.; Pascual, M.A.; Ajossa, S.; Gerada, M.; Bargellini, R.; Virgilio, B.; Melis, G.B. Diagnosis of the Most Frequent Benign Ovarian Cysts: Is Ultrasonography Accurate and Reproducible? J. Women’s Health 2009, 18, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reginelli, A.; Giacobbe, G.; Del Canto, M.T.; Alessandrella, M.; Balestrucci, G.; Urraro, F.; Russo, G.M.; Gallo, L.; Danti, G.; Frittoli, B.; et al. Peritoneal Carcinosis: What the Radiologist Needs to Know. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, P.F.; Hsieh, S.C.; Chien, J.C.W.; Fang, C.L.; Chan, W.P.; Yu, C. Malignant transformation of an ovarian mature cystic teratoma: Computed tomography findings. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2005, 271, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, H.W.; Chan, C.Y.; Lim, K.E.; Chang, H.C. Ruptured Ovarian Cystic Teratoma with Peritoneal Reaction: A Case Report. J. Radiol. Sci. 2015, 40, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ruptured ovarian teratoma with granulomatous peritonitis. Hong Kong Med. J. 2019, 25, e1–e2.

- Kishore, R.; Lambodari, P.; Verma, K.; Khan, A.; Singh, N. A huge mesenteric teratoma in reproductive age woman: A case report. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 10, 4590–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.R.; Ha, S.Y.; Shin, J.W.; Lim, S.; Park, C.Y.; Cho, H.Y. Primary ovarian mixed strumal and mucinous carcinoid arising in an ovarian mature cystic teratoma. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2016, 42, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaane, P.; Huebener, K.H. Computed Tomography of Cystic Ovarian Teratomas with Gravity-Dependent Layering. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1983, 7, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.H.; Kim, S.S. Peritoneal Carcinomatosis and Its Mimics: Review of CT Findings for Differential Diagnosis. J. Belg. Soc. Radiol. 2020, 104, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, T.; Adejolu, M.; deSouza, N.M. Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Ovarian Cancer: Exploiting Strengths and Understanding Limitations. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenc, T.; Popić, J.; Vidjak, V. Magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of malignant gynaecological tumours. Med. Flum. 2022, 58, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaillard, F. Peritoneal Metastases. Available online: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/peritoneal-metastases?lang=us (accessed on 15 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Low, R.N.; Gurney, J. Diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI) in the oncology patient: Value of breathhold DWI compared to unenhanced and gadolinium-enhanced MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2007, 25, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicchetti, M.; Simone, G.; Giannarini, G.; Girometti, R.; Briganti, A.; Brunocilla, E.; Cardone, G.; De Cobelli, F.; Gaudiano, C.; Del Giudice, F.; et al. A novel pathway to detect muscle-invasive bladder cancer based on integrated clinical features and VI-RADS score on MRI: Results of a prospective multicenter study. La Radiol. Med. 2022, 127, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipollari, S.; Pecoraro, M.; Forookhi, A.; Laschena, L.; Bicchetti, M.; Messina, E.; Lucciola, S.; Catalano, C.; Panebianco, V. Biparametric prostate MRI: Impact of a deep learning-based software and of quantitative ADC values on the inter-reader agreement of experienced and inexperienced readers. La Radiol. Med. 2022, 127, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfannenberg, C.; Schwenzer, N.F.; Bruecher, B.L. State-of-the-art imaging of peritoneal carcinomatosis. RoFo 2012, 184, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathod, K.; Kale, H.; Narlawar, R.; Hardikar, J.; Kulkarni, V.; Joseph, J. Unusual “floating balls” appearance of an ovarian cystic teratoma: Sonographic and CT findings. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2001, 29, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, A.Y.; Sun, D.C.; Ohliger, M.A.; Abuzahriyeh, T.; Choi, H.H. Boba sign: A novel sign for floating balls within a mature cystic teratoma. Abdom. Radiol. 2020, 45, 2931–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).