Socioeconomic and Other Risk Factors for Retear after Arthroscopic Surgery for Nontraumatic Rotator Cuff Tear

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

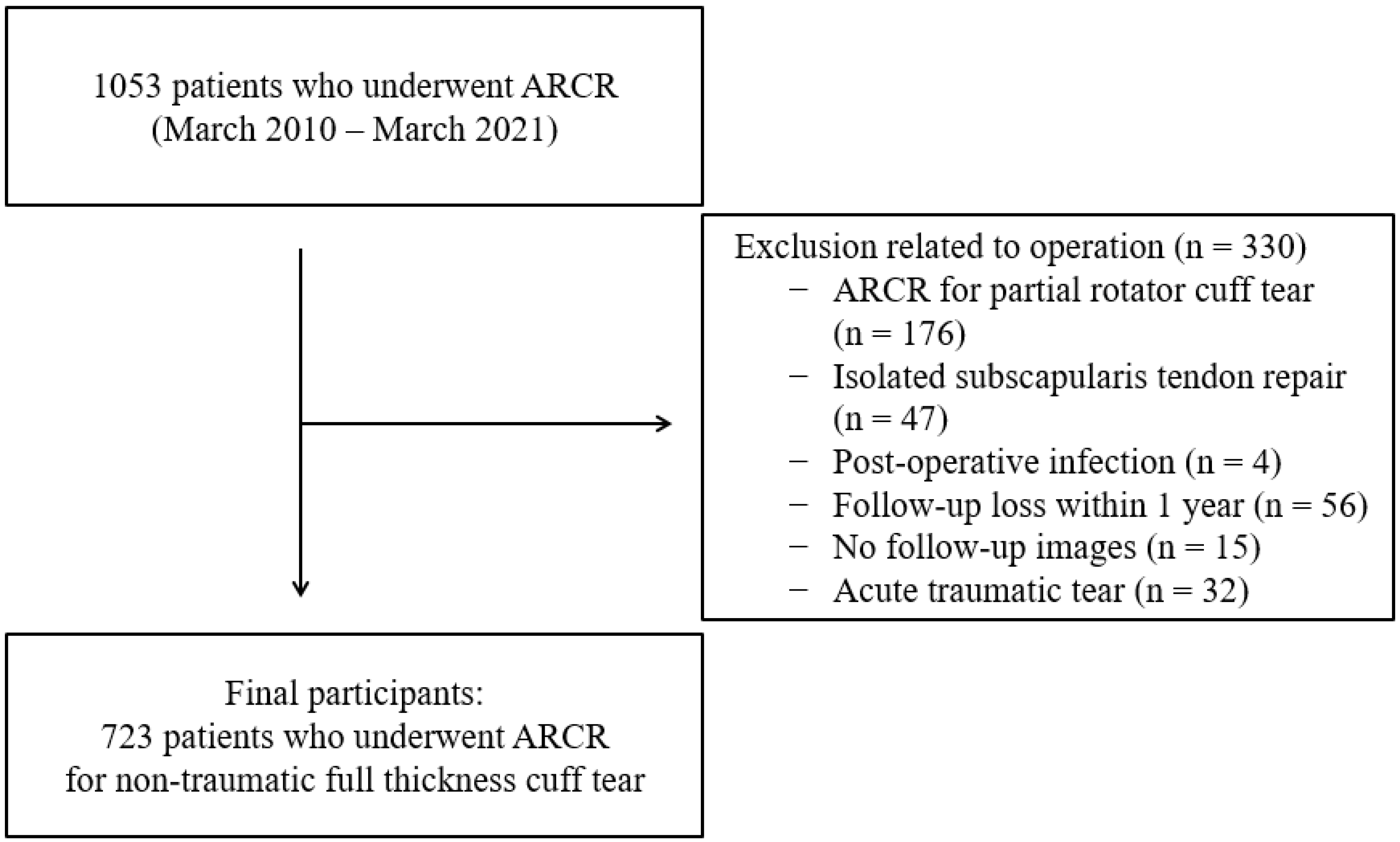

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Data

3.2. Comparison of Independent Variables According to Retearing

3.3. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis

3.4. Influence of Tested Factors on the Retear Risk after ARCR According to Sex

3.5. Influence of the Tested Factors on the Retear Risk after ARCR According to the Area of Residence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, J.; Luo, M.; Pan, J.; Liang, G.; Feng, W.; Zeng, L.; Yang, W.; Liu, J. Risk factors affecting rotator cuff retear after arthroscopic repair: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021, 30, 2660–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandalia, K.; Ames, A.; Parzick, J.C.; Ives, K.; Ross, G.; Shah, S. Social determinants of health influence clinical outcomes of patients undergoing rotator cuff repair: A systemic review. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023, 30, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C.H.; Ye, H.U.; Jung, J.W.; Lee, Y.K. Gender affects early postoperative outcomes of rotator cuff repair. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2015, 7, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjou, H.; Lincoln, S.; Macritchie, I.; Richards, R.R.; Medeiros, D.; Elmaraghy, A. Sex and gener disparity in pathology, disability, referral pattern, and wait time for surgery in workers with shoulder injury. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flurin, P.H.; Hardy, P.; Abadie, P.; Boileau, P.; Collin, P.; Deranlot, J.; Desmoineaux, P.; Duport, M.; Essig, J.; Godenèche, A.; et al. French Arthroscopy Society. Arthroscopic repair of the rotator cuff: Prospective study of tendon healing after 70 years of age in 145 patients. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2013, 99, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galatz, L.M.; Ball, C.M.; Teefey, S.A.; Middleton, W.D.; Yamaguchi, K. The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2004, 86, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, G.H.; Liu, J.N.; Wong, A.; Cordasco, F.; Dines, D.M.; Dines, J.S.; Gulotta, L.V.; Warren, R. Hyperlipidemia increases the risk of retear after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017, 26, 2086–2090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Longo, U.G.; Carnevale, A.; Piergentili, I.; Berton, A.; Candela, V.; Schena, E.; Denaro, V. Retears rates after rotator cuff surgery: A systematic review and meta-anaylisis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.; Shin, D.C.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, K. Prevalence of asymptomatic rotator cuff tear and their related factors in the Korean population. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017, 26, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Diebold, G.; Lam, P.; Walton, J.; Murrell, G.A.C. Relationship between age and rotator cuff retear: A study of 1,600 consecutive rotator cuff repairs. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2017, 99, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Ditsios, K.; Middleton, W.D.; Hildebolt, C.F.; Galatz, L.M.; Teefey, S.A. The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease: A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2006, 88, 1699–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, J.Y.; Santiago-Torres, J.E.; Rimmke, N.; Flanigan, D.C. Smoking predisposes to rotator cuff pathology and shoulder dysfunction: A systematic review. Arthroscopy 2015, 31, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchior, M.; Roquelaure, Y.; Evanoff, B.; Chastang, J.F.; Ha, C.; Imbernon, E.; Goldberg, M.; Leclerc, A. Pays de la Loire Study Group. Why are manual workers at high risk of upper limb disorders? The role of physical work factors in a random sample of workers in France (the Pays de la Loire study). Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 63, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Takagishi, K.; Osawa, T.; Yanagawa, T.; Nakajima, D.; Shitara, H.; Kobayashi, T. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010, 19, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.S.; Jeong, J.Y.; Park, C.D.; Kang, S.G.; Yoo, J.C. Evaluation of the risk factors for a rotator cuff retear after repair surgery. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45, 1755–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.W.; Park, C.K.; Woo, S.H.; Kim, T.W.; Moon, M.H.; Yang, J.H.; Choi, M.H. Factors influencing the size of a non-traumatic full-thickness rotator cuff tear: Focusing on socioeconomic factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penman-Aguilar, A.; Talih, M.; Huang, D.; Moonesinghe, R.; Bouye, K.; Beckles, G. Measurement of health disparities, health inequities, and social determinants of health to support the advancement of health equity. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2016, 22, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.H.; Yang, J.H.; Seo, J.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kang, S.W. Prevalence and diagnosis experience of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women over 50: Focusing on socioeconomic factors. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putrik, P.; Ramiro, S.; Chorus, A.M.; Keszei, A.P.; Boonen, A. Socioeconomic inequities in perceived health among patients with musculoskeletal disorders compared with other chronic disorders: Results from a cross-sectional Dutch study. RMD Open 2015, 1, e000045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, P.K.; Thillemann, T.M.; Pedersen, A.B.; Søballe, K.; Johnsen, S.P. Socioeconomic inequality in clinical outcome among hip fracture patients: A nationwide cohort study. Osteoporos. Int. 2017, 28, 1233–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.C.; Sosa, M.; Saavedra, P.; Lainez, P.; Marrero, M.; Torres, M.; Medina, C.D. Poverty is a risk factor for osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 20, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrack, R.L.; Ruh, E.L.; Chen, J.; Lombardi, A.V.; Berend, K.R.; Parvizi, J.; Valle, C.J.D.; Hamiltom, W.G.; Nunley, R.M. Impact of socioeconomic factors on outcome of total knee arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2014, 472, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen Butler, R.; Rosenzweig, S.; Myers, L.; Barrack, R.L. The Frank Stinchfield Award: The impact of socioeconomic factors on outcome after THA: A prospective, randomized study. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2011, 469, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugaya, H.; Maeda, K.; Matsuki, K.; Moriishi, J. Functional and structural outcome after arthroscopic full-thickness rotator cuff repair: Single-row versus dual-row fixation. Arthroscopy 2005, 21, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.M.; Kim, Y.I. 2019 Medical Aid Statistics; Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service National Health Insurance Service: Ganwon-do, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M.H. The impact of basic livelihoods condition on the current smoking: Applying the counterfactual model. Korea J. Health Educ. Promot. 2019, 36, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C.G.; Floyd, S.B.; Thigpen, C.A.; Tokish, J.M.; Chen, B.; Brooks, J.M. Treatment for rotator cuff tear is influenced by demographics and characteristics of the area where patients live. JB JS Open Access 2018, 3, e0005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, I.Y.; Jung, H.W.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, K.I.; Kim, K.W.; Oh, H.; Ji, M.Y.; Lee, E.; Kim, D.H. Rural and urban disparities in frailty and aging-related health conditions in Korea. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 908–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.H. Socioeconomic differences among community-dwelling diabetic adults screened for diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy: The 2015 Korean Community Health Survey. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.J.; Nam, K.P.; Yeo, H.J.; Rhee, S.M.; Oh, J.H. Retear after Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair results in functional outcome deterioration over time. Arthroscopy 2022, 38, 2399–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.B.; Gwark, J.Y.; Im, J.H.; Jung, J.; Na, J.B.; Yoon, C.H. Factors associated with atraumatic posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2018, 100, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdari, S.; Donegan, R.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Galatz, L.M.; Yamaguchi, K.; Keener, J.D. Factors affecting outcome after structural failure of repaired rotator cuff tears. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2014, 96, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P.A.; Cubbin, C.; Egerter, S.; Williams, D.R.; Pamuk, E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.W.; Lee, S.Y.; Moon, O.R. Inequalities in cancer incidence and mortality across income groups and policy implications in South Korea. Public Health 2008, 122, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, S.S.; Razak, F.; Davis, A.D.; Jacobs, R.; Vuksan, V.; Teo, K.; Yusuf, S. Social disadvantage and cardiovascular disease: Development of an index and analysis of age, sex, and ethnicity effects. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 35, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, A.P.; Feely, B.T.; Lansdown, D.A. Low socioeconomic status worsens access to care and outcoms for rotator cuff repair: A scoping review. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022, 2, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, M.J.; Penvose, I.; Curry, E.J.; Galvin, J.W.; Li, X. Insurance status affects access to physical therapy following rotator cuff repair surgery: A comparison of privately insured and Medicaid patients. Orthop. Rev. 2019, 11, 7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, E.J.; Penvose, I.; Knapp, B.; Parisien, R.L.; Li, X. National Disparities in Access to Physical Therapy After Rotator Cuff Repair Between Patients with Medicaid versus Private Health Insurance. JSES Int. 2021, 5, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Jung, K.H.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, U.S.; Hwang, D.H. Factors affecting rotator cuff integrity after arthroscopic repair for medium-sized or larger cuff tears: A retrospective cohort study. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018, 27, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molen, H.F.; Foresti, C.; Daams, J.G.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W.; Kuijer, P. Work-related risk factors for specific shoulder disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 401 | 55.5 |

| Male | 322 | 44.5 | |

| Age (mean ± SD, range; years) | 62.4 ± 8.0, 30–87 | ||

| Age group (years) | 30–49 | 30 | 4.1 |

| 50–69 | 549 | 75.9 | |

| ≥70 | 144 | 19.9 | |

| Occupation | Non-manual | 254 | 35.1 |

| Manual | 469 | 64.9 | |

| Education | ≤Middle school | 348 | 48.1 |

| ≥High school | 375 | 51.9 | |

| Area of residence | Urban | 485 | 67.1 |

| Rural | 238 | 32.9 | |

| Insurance type | NHI | 681 | 94.2 |

| Medicaid | 42 | 5.8 | |

| Obesity | No | 393 | 54.4 |

| Yes | 330 | 45.6 | |

| Diabetes | No | 603 | 83.4 |

| Yes | 120 | 16.6 | |

| Symptom duration (mean ± SD, range; years) | 1.8 ± 1.7, 1–10 | ||

| Tear size (mean ± SD, range; mm) | 21.8 ± 12.5, 5–49 | ||

| No Retear | Retear | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Sex | Female | 317 | 55.4 | 84 | 55.6 | 0.963 |

| Male | 255 | 44.6 | 67 | 44.4 | ||

| Age | 61.8, 8.0 | 64.7, 7.7 | <0.001 | |||

| Age group (years) | 30–49 | 27 | 4.7 | 3 | 2.0 | <0.001 |

| 50–69 | 448 | 78.3 | 101 | 66.9 | ||

| ≥70 | 97 | 17.0 | 47 | 31.1 | ||

| Occupation | Non-manual | 206 | 36.0 | 48 | 31.8 | 0.333 |

| Manual | 366 | 64.0 | 103 | 68.2 | ||

| Education | ≤Middle school | 286 | 50.0 | 62 | 41.1 | 0.05 |

| ≥High school | 286 | 50.0 | 89 | 58.9 | ||

| Area of residence | Urban | 383 | 67.0 | 102 | 67.5 | 0.891 |

| Rural | 189 | 33.0 | 48 | 31.8 | ||

| Insurance type | NHI | 549 | 96.0 | 132 | 87.4 | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 23 | 4.0 | 19 | 12.6 | ||

| Obesity | No | 313 | 54.7 | 80 | 53.0 | 0.703 |

| Yes | 259 | 45.3 | 71 | 47.0 | ||

| Diabetes | No | 494 | 86.4 | 109 | 72.2 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 78 | 13.6 | 42 | 27.8 | ||

| Tear size (mm) | 19.8 ± 11.3 | 29.5 ± 13.7 | <0.001 | |||

| Symptom duration (years) | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 2.4 ± 1.7 | <0.001 | |||

| OR | LL | UL | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Reference | |||

| Female | 0.81 | 0.52 | 1.26 | 0.352 | |

| Age | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.07 | 0.017 | |

| Occupation | Non-manual | Reference | |||

| Manual | 1.95 | 1.23 | 3.11 | 0.005 | |

| Education | ≥High school | Reference | |||

| ≤Middle school | 0.92 | 0.58 | 1.45 | 0.718 | |

| Area of residence | Urban | Reference | |||

| Rural | 1.06 | 0.69 | 1.63 | 0.789 | |

| Insurance type | NHI | Reference | |||

| Medicaid | 4.34 | 2.09 | 9.02 | <0.001 | |

| Obesity | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.97 | 0.65 | 1.46 | 0.902 | |

| Diabetes | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 2.43 | 1.49 | 3.95 | <0.001 | |

| Tear size | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.08 | <0.001 | |

| Symptom duration | 1.21 | 1.09 | 1.33 | <0.001 | |

| Male | Female | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | LL | UL | p-Value | OR | LL | UL | p-Value | ||

| Age | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.09 | 0.072 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.07 | 0.186 | |

| Occupation | Non-manual | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Manual | 1.88 | 0.95 | 3.74 | 0.071 | 2.23 | 1.11 | 4.49 | 0.025 | |

| Education | ≥High school | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| ≤Middle school | 0.98 | 0.50 | 1.92 | 0.964 | 1.05 | 0.55 | 1.99 | 0.886 | |

| Area of residence | Urban | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Rural | 1.09 | 0.55 | 2.13 | 0.811 | 1.12 | 0.63 | 2.00 | 0.698 | |

| Insurance type | NHI | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Medicaid | 8.34 | 2.78 | 25.07 | <0.001 | 2.39 | 0.84 | 6.85 | 0.104 | |

| Obesity | No | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 1.04 | 0.55 | 1.95 | 0.905 | 1.06 | 0.61 | 1.83 | 0.845 | |

| Diabetes | No | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 5.69 | 2.83 | 11.43 | <0.001 | 0.93 | 0.43 | 2.01 | 0.847 | |

| Tear size | 1.06 | 1.03 | 1.08 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.09 | <0.001 | |

| Symptom duration | 1.14 | 0.98 | 1.32 | 0.100 | 1.30 | 1.13 | 1.51 | <0.001 | |

| Rural | Urban | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | LL | UL | p-Value | OR | LL | UL | p-Value | ||

| Sex | Male | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Female | 0.85 | 0.38 | 1.89 | 0.684 | 0.74 | 0.43 | 1.28 | 0.282 | |

| Age | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.08 | 0.372 | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.08 | 0.015 | |

| Occupation | Non-manual | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Manual | 2.44 | 1.07 | 5.59 | 0.034 | 1.76 | 1.00 | 3.10 | 0.052 | |

| Education | ≥High school | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| ≤Middle school | 0.81 | 0.36 | 1.82 | 0.606 | 0.98 | 0.56 | 1.71 | 0.951 | |

| Insurance type | NHI | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Medicaid | 7.96 | 1.48 | 42.72 | 0.015 | 3.80 | 1.69 | 8.55 | 0.001 | |

| Obesity | No | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 0.71 | 0.34 | 1.48 | 0.355 | 1.12 | 0.69 | 1.83 | 0.649 | |

| Diabetes | No | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 4.94 | 2.11 | 11.56 | <0.001 | 1.62 | 0.88 | 3.00 | 0.123 | |

| Tear size | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.10 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 1.04 | 1.08 | <0.001 | |

| Symptom duration | 1.23 | 0.95 | 1.60 | 0.120 | 1.19 | 1.07 | 1.33 | 0.002 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.S.; Suh, K.T.; Shin, W.C.; Bae, J.Y.; Goh, T.S.; Jung, S.W.; Choi, M.-H.; Kang, S.-W. Socioeconomic and Other Risk Factors for Retear after Arthroscopic Surgery for Nontraumatic Rotator Cuff Tear. Medicina 2024, 60, 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60040640

Lee JS, Suh KT, Shin WC, Bae JY, Goh TS, Jung SW, Choi M-H, Kang S-W. Socioeconomic and Other Risk Factors for Retear after Arthroscopic Surgery for Nontraumatic Rotator Cuff Tear. Medicina. 2024; 60(4):640. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60040640

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jung Sub, Kuen Tak Suh, Won Chul Shin, Jung Yun Bae, Tae Sik Goh, Sung Won Jung, Min-Hyeok Choi, and Suk-Woong Kang. 2024. "Socioeconomic and Other Risk Factors for Retear after Arthroscopic Surgery for Nontraumatic Rotator Cuff Tear" Medicina 60, no. 4: 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60040640

APA StyleLee, J. S., Suh, K. T., Shin, W. C., Bae, J. Y., Goh, T. S., Jung, S. W., Choi, M.-H., & Kang, S.-W. (2024). Socioeconomic and Other Risk Factors for Retear after Arthroscopic Surgery for Nontraumatic Rotator Cuff Tear. Medicina, 60(4), 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60040640