Abstract

Background and Objectives: End-stage kidney disease (ESKD) is a major risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. This study aims to evaluate the contribution of traditional risk factors to the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients on dialysis. Materials and Methods: In this study, 54 patients on dialysis with angina symptoms or a positive exercise stress test underwent coronary angiography. Lesions with obstruction >70% lumen diameter of the coronary artery were considered significant. Traditional risk factors included hypertension, diabetes, smoking, dyslipidemia, age, gender, and time spent on dialysis. Results: Out of 54 participants, 41 (75.92%) were men and 13 (24.07%) women. CAD was present in 34 (62.96%) patients, and 20 (37.03%) patients were without CAD. The average age of the participants was 66.51 years. In the group with CAD, the average age was 69.52 years with an average time spent on dialysis of 2.73 years. In the group without CAD, the average age was 61.40 years with a time spent on dialysis of 2.35 years. Hypertension was present in 92.59% of all participants and 97.05% of those with CAD. Diabetes was present in 41.17 patients with CAD and 40% of those without CAD. Dyslipidemia was present in 76.47 participants with CAD and in 40% of those without CAD. Smoking was noticed in 35.29% of the participants with CAD and 57.14% of those without CAD. Besides hypertension, significant predictors for the development of CAD in patients on dialysis were dyslipidemia (OR 3.698, Cl 1.005–13.608, p = 0.049) and age (OR 1.056, Cl 1.004–1.110, p = 0.033). Conclusions: Among the traditional risk factors, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and age are the predictors for the development of CAD in patients on dialysis. Further large randomized clinical studies are needed to clarify the role of traditional risk factors for CAD in patients with ESKD.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) treated with the different modalities of dialysis. One of the most important manifestations of CVD in chronic kidney disease (CKD) is coronary artery disease (CAD). The prevalence of CAD and the number of significant coronary stenoses increases with the decrease in kidney function [1]. CVD results from traditional risk factors like hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, and age, but also from non-traditional risk factors like arteriosclerosis, vascular calcifications, endothelial dysfunction, and low-grade inflammation [2,3]. Besides CAD, this process leads to left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), diffuse fibrosis, left ventricular dilatation, and heart failure [4]. Cardiovascular mortality among patients on dialysis is 10–20 times higher compared to that of the general population of the same age and it is responsible for 50% of deaths among patients with ESKD [5]. According to the results from the US Kidney Data System, the prevalence of CAD in the CKD population is 39% versus 16% in the non-CKD population. The situation among patients undergoing hemodialysis is even worse, with the prevalence of CAD at 42% and that of CVD at 70% [6].

ESKD modifies the clinical presentation of the traditional symptoms of CAD. Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) with chest pain was presented in 44% of patients on dialysis compared with 68% of no-dialysis patients [7]. The recognition of CAD is more difficult with the persistence of anemia and fatigue common among patients on dialysis. Low functional capacity and achieving the threshold for angina pain also limit recognition of symptoms of angina pain in these patients [8]. Electrocardiogram (ECG) changes in angina pain are less common among patients on dialysis. A lower proportion of patients on dialysis presented with ST-segment changes than non-dialyzed patients. ECG changes are often present in patients with ESKD in the form of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), ST-segment, and T-wave abnormalities [9]. Serum biomarkers like cardiac troponin (high-sensitivity troponin-I and troponin-T) have limited sensitivity because they are often persistently elevated in patients with ESKD due to LVH, diastolic dysfunction, and volume overload in the absence of acute coronary syndrome [10].

Coronary angiography (CA) is considered the gold standard for diagnosing coronary stenosis in CAD. Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) and coronary artery calcium score (CACS) might be used with caution in patients with ESKD, but the evidence comparing the accuracy of CCTA with CA in this population is limited. Low specificity could be explained by the high calcium burden in coronary arteries without significant stenosis [11,12]. Considering the limited number of studies on the development of coronary disease in dialysis patients and the presence of well-known risk factors, this study aimed to assess the presence and impact of traditional risk factors of coronary artery disease in dialysis patients. Traditional risk factors for CAD (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, and age) as well as time spent on dialysis were analyzed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This retrospective observational study was conducted for the period from 2019 to 2023. The patients included in this study were 54 adult patients over 18 years of age receiving dialysis: 51 on hemodialysis and 3 on peritoneal dialysis, all undergoing CA at a single center.

2.2. Data Collection

The age and gender of patients, as well as conventional cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, and history of peripheral vascular disease) and duration of dialysis, were collected from the patients’ medical records.

2.3. Procedures

Inclusion indications for coronary angiography (CA) included angina symptoms or a positive exercise stress test (ergometry) in patients undergoing screening for kidney transplantation. Patients who did not have angina symptoms or had a negative exercise stress test (ergometry) were excluded from the study. Significant coronary artery lesions were considered significant if the stenosis was more than 70% of the luminal diameter.

CA was performed via the radial artery; only in cases where access via the radial artery was not possible was the femoral artery used. Lesions were coded according to the degree of obstruction, from normal to non-obstructive (<70% stenosis) and obstructive disease (>70% stenosis).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for categorical variables are presented as proportions and percentages, while numerical data are presented with the mean and standard deviation. The ANOVA test was used to examine differences in the incidence of coronary artery disease concerning years of dialysis. Logistic regression was performed to identify predictors of coronary artery disease in dialysis patients. A significance level of α = 0.05 was used as a criterion for the statistical significance of the results obtained. The data were analyzed using STATISTICA software version 14.0.0.15 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2018).

3. Results

Of the 54 participants in the study, 41 (75.92%) were men and 13 (24.07%) were women. The most common underlying condition for ESKD was hypertensive/ischemic nephropathy (33%), diabetic nephropathy (28%), glomerulonephritis (22%), polycystic kidney disease (4%), and other conditions (13%). The average age of the participants was 66.51 years (SD = 13.12) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age of participants and duration of dialysis (n = 54).

Participants who were diagnosed with coronary artery disease were older than participants who were not diagnosed with coronary artery disease (p = 0.026). The difference between participants regarding the duration of dialysis was not recorded (p = 0.526) (Table 1).

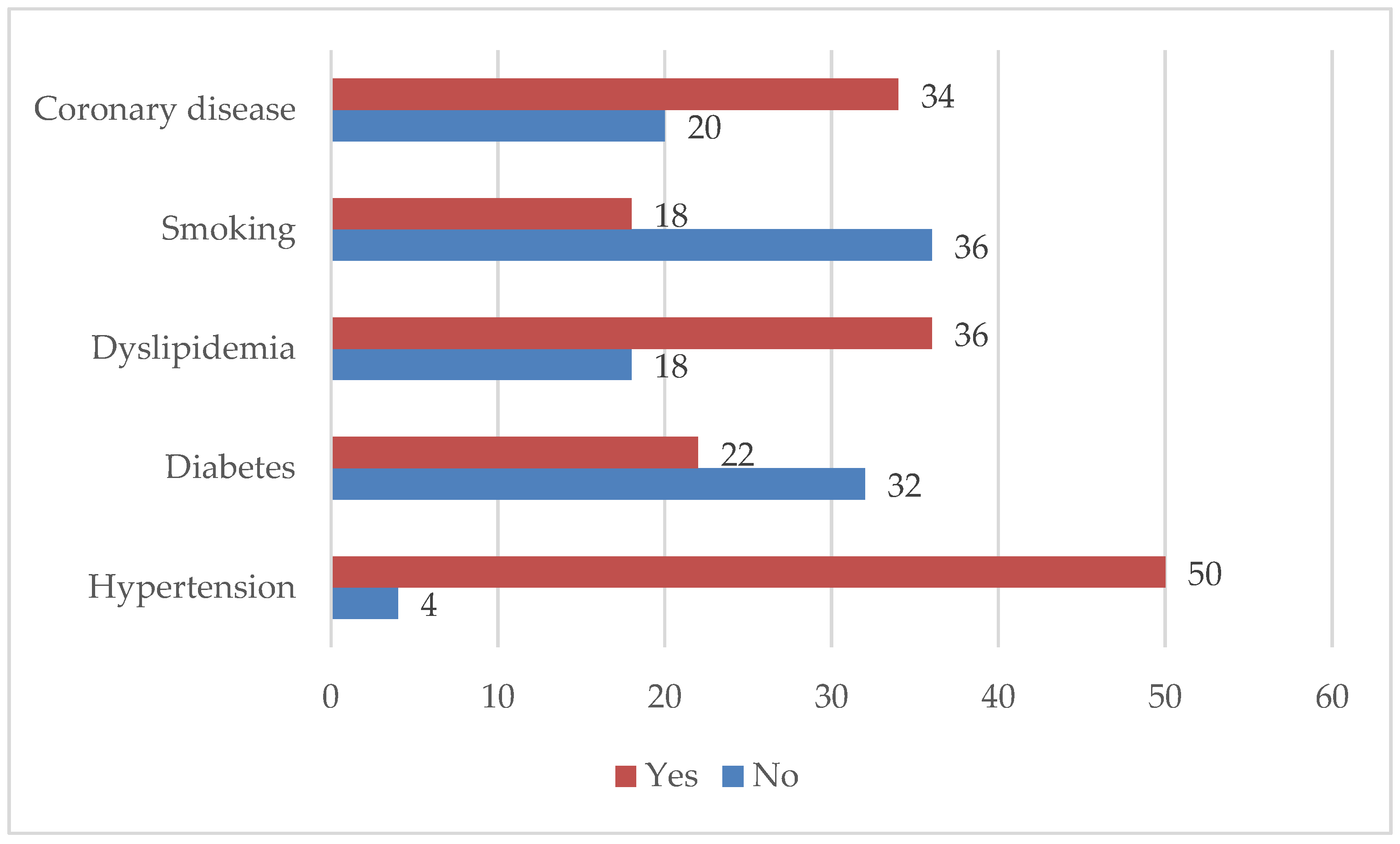

Most of the participants had a diagnosis of hypertension (n = 50; 92.59%), followed by dyslipidemia (n = 36; 66.66%). A total of 18 (33.33%) participants consumed tobacco products. More than half of the participants (32.96%) were found to have coronary artery disease on diagnostic coronary angiography (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of the participants concerning the presence of risk factors (n = 54).

The presence of hypertension was recorded in almost all participants diagnosed with coronary artery disease (n = 33), while a total of 26 patients with coronary artery disease were found to have dyslipidemia. The majority of participants diagnosed with coronary artery disease were men (n = 26) and most participants (n = 22) did not consume tobacco products (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution and characteristics of participants with regard to the presence of coronary artery disease (n = 54).

The results of the ANOVA test did not record a statistically significant difference (p = 0.120) in the incidence of coronary disease among the participants regarding the duration of dialysis. Therefore, the duration of dialysis, as well as the presence of hypertension due to its presence in almost all subjects with coronary artery disease, was excluded from further analysis.

After applying logistic regression analysis, age (OR 1.056, 95% Cl 1.004–1.110, p = 0.033) and dyslipidemia (OR 3.698, 95% Cl 1.005–13.608, p = 0.049) were recorded as statistically significant predictors of coronary artery disease in the participants of this study. With an increase of one year of life, the chance of coronary disease increased 1.05 times. Furthermore, participants diagnosed with dyslipidemia had a 3.69 times higher risk of developing coronary artery disease (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis for predictors of coronary artery disease in dialysis patients (n = 54).

4. Discussion

Patients with ESRD who require dialysis have a significantly increased risk of morbidity and mortality from CVD. CAD is the major clinical manifestation of a worse prognosis for these patients. It is more likely to develop acute myocardial infarction (AMI) than stable angina as an initial clinical manifestation of CAD. AMI is more likely to be a non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (nSTEMI) than an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) [13,14]. Relatively common in dialysis patients is a sudden death perhaps because of changes in electrolytes, volume, and drug concentration which may trigger arrhythmias in patients with LVH and heart failure, which are common in these patients [4].

Hypertension is the most common CVD risk factor in patients with ESKD. In our study group, it was present in 92% of all participants and in 97% of those with CAD, which confirms hypertension as the most important risk factor for CAD not only in patients with ESKD. Similar results were found in the study by Vasuveda et al. in patients with stable CAD and ESKD who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) with a hypertension prevalence of 97% [15]. In a study on predictors of CAD progression in high-risk patients with recurrent symptoms, Fatah et al. reported a 71% prevalence of hypertension [16].

In addition, this study found that dyslipidemia is an important risk factor for the development of CAD in ESKD patients, increasing the risk by 3.69 times. The treatment of dyslipidemia in patients with ESKD is controversial. The benefit of statin-based treatment in reducing serious vascular events is lower with the decline in the glomerular filtration rate, with no clear evidence for dialysis patients [17].

Also, age was found to be a risk factor for the development of CAD in patients on dialysis with a chance of developing CAD of 1.05 per year. This was not noticed for the years spent on dialysis. Chen et al. found, in a study of Asian dialysis patients, that higher all-cause mortality was associated with a dialysis time greater than 3 years in patients undergoing CABG [18]. In this study, both groups, with and without CAD, spent less than 3 years on dialysis; those with CAD spent 2.73 years and those without CAD spent 2.35 years on dialysis, which may suggest that a much longer duration of dialysis may be associated with a higher risk of developing CAD.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are among the strongest risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) [19]. This includes every aspect of CVD, including atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), heart failure (HF), valvular heart disease, peripheral arterial disease (PAD), stroke, and arrhythmias [20]. In addition, the overall mortality associated with CVD in these conditions remains high. The coexistence of these conditions has additive and sometimes multiplicative effects on these outcomes [21]. Based on the results of this study, 41.17% of patients with CAD were diabetic patients, but 40% without CAD had diabetes as an additional risk factor, so we found no association between diabetes and the risk of CAD in patients on dialysis.

According to the literature, smoking increases all causes of death in dialysis patients and leads to a 10-year reduction in life expectancy. It also leads to a 36% higher risk of cardiovascular events [22,23]. It is important to emphasize that several studies have found that smoking increases the incidence of peripheral vascular events and heart failure. However, an increased incidence of cerebrovascular or coronary vascular events was not found [24]. Furthermore, smoking accelerates atherosclerotic disease, impairs endothelial function, increases blood pressure, and increases sympathetic outflow [23]. Smoking before dialysis causes acute elevations in blood pressure, leading to more antihypertensive medications being prescribed which interfere with adequate fluid withdrawal due to intradialytic hypotension [23]. In this study, 35% of patients were active smokers, which is a significantly higher percentage than the results found in the literature (15%) [22], but is very similar to the results of 31% of smokers from reports of previous Croatian epidemiological studies in the general population [25]. An association between smoking and the progression of coronary artery disease in smokers among the dialysis population was not found in this study.

There are different treatment options for CAD in advanced CKD: conservative and interventional strategies such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) [26]. Reports from the ISCHEMIA-CKD trial provided no evidence that the initial invasive strategy reduced the risk of death or non-fatal myocardial infarction in these patients compared with the initial conservative strategy [27]. For the invasive approach, there is still no clear evidence of the benefits of CABG or PCI. In the SYNTAX trial [28], there is an advantage of CABG, EXCEL showed no significant difference between PCI and CABG [29], and in a national study from Taiwan, PCI with a drug-eluting stent was associated with better survival in dialysis patients [30].

Among patients on dialysis, there is a high prevalence of asymptomatic patients, estimated to be between 42 and 54% according to some reports [31]. The KDIGO guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients recommend annual CAD evaluation in patients with diabetes on the waiting list for transplantation as a non-invasive screening [32]. Currently, routine invasive screening for CAD is not part of clinical practice for these patients. However, in the future, it may be necessary to consider implementing this option to prevent CAD and promptly improve dialysis patients’ treatment. Although this study provides valuable results and information that may potentially contribute to deciding on the introduction of additional preventive diagnostic procedures for dialysis patients, the fact that this is a relatively small sample of patients from a single healthcare institution that cares for the population of a relatively limited geographical area should also be taken into account. Furthermore, we did not collect other parameters of prognostic value in this study, such as laboratory measurements and pharmacotherapy, which may also have a significant impact on patient outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Hypertension, dyslipidemia, and age were significant predictors for the development of CAD in patients on dialysis, and better control of hypertension and dyslipidemia is necessary to prevent the occurrence of CAD in these patients. Further large randomized clinical trials are needed to clarify the role of traditional risk factors for CAD in patients with ESKD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.N., P.G.P., M.V., M.S., J.P., M.B., Z.B., J.V.L. and I.G.; methodology, D.N., P.G.P., M.V., M.S., J.P., M.B., Z.B. and I.G.; software, D.N. and I.G.; validation, D.N., P.G.P., M.V., M.S. and J.P.; formal analysis, D.N. and I.G.; investigation, D.N., P.G.P., M.V., M.S., J.P., M.B., Z.B. and J.V.L.; resources, D.N., M.S., J.P., M.B. and Z.B.; data curation, D.N., P.G.P., M.V., M.S., J.P., M.B., Z.B. and J.V.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.N., P.G.P., M.V., M.S., J.P., M.B., Z.B., J.V.L. and I.G.; writing—review and editing, D.N., P.G.P., M.V., M.S., J.P., M.B., Z.B., J.V.L. and I.G.; visualization, D.N. and I.G.; supervision, J.P.; project administration, D.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the recommendations of the Institutional Ethics Committee of General Hospital Zadar (Approval Code: 01-5661/12-9/24; Approval Date: 3 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will make available the data supporting this article’s conclusions on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the participants who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fujii, H.; Kono, K.; Nishi, S. Characteristics of coronary artery disease in chronic kidney disease. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2019, 23, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansevoort, R.T.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Jafar, T.H.; Heerspink, H.J.; Mann, J.F.; Matsushita, K.; Wen, C.P. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet 2013, 382, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, J.O.; Jefferies, H.J.; Selby, N.M.; McIntyre, C.W. Hemodialysis-induced cardiac injury: Determinants and associated outcomes. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanner, C.; Amann, K.; Shoji, T. The heart and vascular system in dialysis. Lancet 2016, 388, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poli, F.E.; Gulsin, G.S.; McCann, G.P.; Burton, J.O.; Graham-Brown, M.P. The assessment of coronary artery disease on patients with end-stage renal disease. Clin. Kidney J. 2019, 12, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, S. Coronary revascularisation in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, C.A.; Littrell, K.; Arko, C.; Frederick, P.D.; Blaney, M. Clinical characteristics of dialysis patients with acute myocardial infarction in the United States: A collaborative project of the United States Renal Data System and the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2007, 116, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarnak, M.J.; Amann, K.; Bangalore, S.; Cavalcante, J.L.; Charytan, D.M.; Craig, J.C.; Gill, J.S.; Hlatky, M.A.; Jardine, A.G.; Landmesser, U.; et al. Conference Participants. Chronic kidney disease and coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1823–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, S.; Yoshizawa, M.; Nakanishi, N.; Yazawa, T.; Yokota, K.; Honda, M.; Sloman, G. Electrocardiographic abnormalities in patients receiving hemodialysis. Am. Heart J. 1996, 131, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, V.S.; Jarolim, P. How to interpret elevated cardiac troponin levels. Circulation 2011, 124, 2350–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Karthikeyan, V.; Poopat, C.; Song, T.; Pantelic, M.; Chattahi, J.; Cavalcante, J.L.; Ananthasubramaniam, K. Coronary computed tomography angiography in dialysis patients undergoing pre-renal transplantation cardiac risk stratification. Cardiol. J. 2010, 17, 349–361. [Google Scholar]

- Jug, B.; Kadakia, J.; Gupta, M.; Papazian, J.; Derakhshani, A.; Koplik, S.; Karlsberg, R.P.; Budoff, M.J. Coronary calcifications and plaque characteristics in patients with end-stage renal disease: A computed tomography study. Coron. Artery Dis. 2013, 24, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, A.S.; Bansal, N.; Chandra, M.; Lathon, P.V.; Fortmann, S.P.; Iribarren, C.; Hsu, C.Y.; Hlatky, M.A.; ADVANCE Study Investigators. Chronic kidney disease and risk for presenting with acute myocardial infarction versus stable exertional angina in adults with coronary heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, G.R.; Li, S.; Herzog, C.A. Trends in discharge claims for acute myocardial infarction among patients on dialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 1379–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudeva, R.; Mehta, H.; Chan, W.C.; Majmundar, M.; Yarlagadda, S.G.; Downey, P.; Daon, E.; Muehlebach, G.; Danter, M.; Zorn, G.; et al. Trends and outcomes for coronary artery bypass grafting in end-stage kidney disease and stable coronary artery disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2024, 1, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, I.; Ahmed, A.M.; Odeh, R.; Alameen, E.; Al-Khateeb, M.; Fadel, E.; Rabai, R.; Ali, D.; Bdeir, B.; Al-Mallah, M.H. Predictors of coronary artery disease progression among high-risk patients with recurrent symptoms. Heart Views 2018, 19, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellström, B.; Holdaas, H.; Jardine, A.G.; Rose, H.; Schmieder, R.; Wilpshaar, W.; Zannad, F.; AURORA Study Group. Effect of rosuvastatin on outcomes in chronic haemodialysis patients: Baseline dana from the AURORA study. Kidney Blood Pres. Res. 2007, 30, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.W.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.S.; Wu, V.C.; Chen, D.Y.; Tsai, F.C.; Hung, M.J.; Chu, P.H.; Lin, P.J.; Chen, T.H. Effect of dialysis dependence and duration on post-coronary artery bypass grafting outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease: A nationwide cohort study in Asia. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 223, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Malik, S.; Budoff, M.J.; Correa, A.; Ashley, K.E.; Selvin, E.; Watson, K.E.; Wong, N.D. Identification and predictors for cardiovascular disease risk equivalents among adults with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 2411–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop-Busui, R.; Januzzi, J.L.; Bruemmer, D.; Butalia, S.; Green, J.B.; Horton, W.B.; Knight, C.; Levi, M.; Rasouli, N.; Richardson, C.R. Heart failure: An underappreciated complication of diabetes. A consensus report of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1670–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papademetriou, V.; Lovato, L.; Doumas, M.; Nylen, E.; Mottl, A.; Cohen, R.M.; Applegate, W.B.; Puntakee, Z.; Yale, J.F.; Cushman, W.C. Chronic kidney disease and intensive glycemic control increase cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2015, 87, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.C.; Thadhani, R.I.; Reviriego-Mendoza, M.; Larkin, J.W.; Maddux, F.W.; Ofsthun, N.J. Association of smoking status with mortality and hospitalization in hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 72, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapolyai, M.; Forró, M.; Lengvárszky, Z.; Fülöp, T. Dialysis patient who smoke are more hypertensive, more fluid overloaded and take more antihypertensive medications than nonsmokers. Ren. Fail. 2020, 42, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebman, S.E.; Lamontagne, S.P.; Huang, L.S.; Messing, S.; Bushinsky, D.A. Smoking in Dialysis Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Mortality and Cardiovascular Morbidity. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2011, 58, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakić, D.; Stipčević, M.; Morić Perić, M.; Bakotić, Z.; Lončar, J.V.; Bačkov, K.; Vojković, M.; Jakab, J.; Včev, A. Chronic medical conditions in Croatian war veterans compared to general popolation: 25 years after the war. Acta Clin. Croat. 2023, 62, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losin, I.; Hagai, K.C.; Pereg, D. The treatment of coronary artery disease in patients with chronic kidney disease: Gaps, challenges, and solutions. Kidney Dis. 2023, 10, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangalore, S.; Maron, D.J.; O’Brien, S.M.; Fleg, J.L.; Kretov, E.I.; Briguori, C.; Kaul, U.; Reynolds, H.R.; Mazurek, T.; Sidhu, M.S.; et al. Management of coronary disease in patients with advanced kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1608–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojevic, M.; Head, S.J.; Mack, M.J.; Mohr, F.W.; Morice, M.C.; Dawkins, K.D.; Holmes, D.R., Jr.; Serruys, P.W.; Kappetein, A.P. The impact of chronic kidney disease on outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with complex coronary artery disease: Five-year follow-up of the SYNTAX trial. Eurointervention 2018, 14, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustino, G.; Mehran, R.; Serruys, P.W.; Sabik, J.F.; Milojevic, M., 3rd; Simonton, C.A.; Puskas, J.D.; Kandzari, D.E.; Morice, M.C.; Taggart, D.P.; et al. Left main revascularization with PCI or CABG in patients with chronic kidney disease: EXCEL trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 754–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.Y.; Yang, J.Y.; Teng, N.C.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, S.H.; Lee, C.L.; Chen, K.L.; Chiu, Y.L.; Hsu, S.P.; Peng, Y.S.; et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention with a drug-eluting stent versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients receiving dialysis: A national study from Taiwan. Kidney Med. 2023, 6, 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vriese, A.S.; Vandecasteele, S.J.; Van den Bergh, B.; De Geeter, F.W. Should we screen for coronary artery disease in asymptomatic chronic dialysis patients? Kidney Int. 2012, 81, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).