Managing Medication Cost Burden: A Qualitative Study Exploring Experiences of People with Disabilities in Canada

Abstract

:1. Introduction

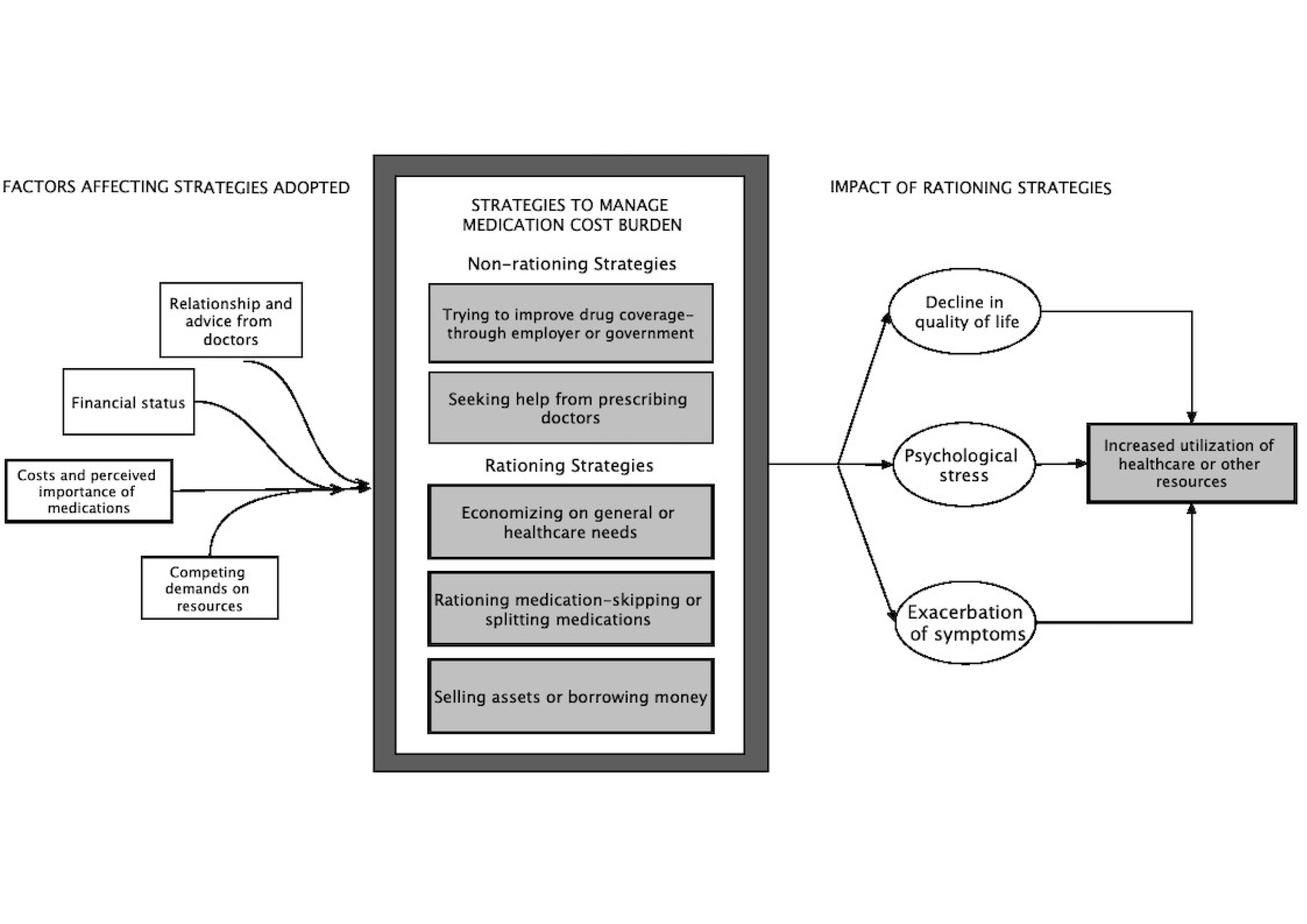

- The strategies that participants adopted to manage their medication cost burden.

- The factors that influenced an individual’s decisions to adopt those strategies.

- The impact of rationing strategies on individuals.

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Strategies to Manage Medication Cost Burden

3.1.1. Trying to Access Public or Employer-Based Drug Benefits

[Drug name 1] was not covered by the provincial Pharmacare, even though [drug name 2] was. I applied it under exceptional drug coverage, and they approved it on a yearly basis like I have to apply for it every year.[P/6]

I am considering going back to work. Part-time, but if needed, full-time too. Right now, I am concerned about money to survive until retirement.[P/5]

I had shift work, and it was very hard on me. In the last years, I tried to make it steady, but my body couldn’t take it. A lot of my disabled friends told me that I was practically killing myself to get those benefits.[P/9]

Trillium, they have a huge [deductible] … you have to use up the deductible first, in order for it to be covered. My pills don’t work out to more than the deductibles, so it doesn’t apply to me. I tried to get on ODSP [Ontario Disability Support Program]. I have been turned down three times. We are (in) No Man’s Land.[P/3]

It is frustrating as I have to submit [paperwork] first, to my insurance company, to my former employer, and then wait for them to get back to me, and then send all of this to Trillium. It’s such a delay. It is very frustrating because you may never know when you will get the money.[P/7]

3.1.2. Seeking Help from Prescribing Doctors

My doctors, all … my psychiatrist, my back specialist, and my family doctor they know I don’t have any benefits, so they always prescribe the cheaper alternative or over the counter alternative…or whatever, just for that reason.[P/2]

My doctor was concerned about me. She would give me the samples for some medication because I had to cut back and she didn’t want to see me pay out of pocket. But with [drug name], it was too costly, and she couldn’t help me there. She tried to find cheaper substitutes or the generic versions, but they were of the same price range.[P/4]

My neurologist has to do that [application for drug benefit], and he is aware of the time-lapse. It has to be done every year. One year, he missed sending in the Section 8 form, and I was without drugs for a whole year. That would have been $4000–$5000 a month if I didn’t have coverage.[P/5]

My family doctor does not [ask me about medication costs]. Most of them do not ask that question. I have to bring it up. The urinary urgency one … it was about $300. I couldn’t get it for several months. I went to my urologist and told him that I couldn’t get it because I couldn’t afford it. At that point, he prescribed one that was less expensive.[P/5]

3.1.3. Economizing on General or Other Healthcare Needs

I have stopped buying new clothes, and I shop at the thrift store. I have changed my spending habits, to make sure that I keep my health. Things like a gym membership, have also gone …[P/5]

I could not have cut back on food, as you can’t survive without eating. But I didn’t buy clothes for years. We didn’t go on any trips forever! I don’t remember the last time we went on a trip. We just cruised along from paycheck to paycheck.[P/4]

I have been needing new tires for my chair for two months (laughs). You have to make choices. Right now, my pressure sores are bad, and so that is my priority. I am not really going out much, stuck in bed, so the chair becomes my second priority.[P/9]

3.1.4. Rationing Medications

When I know I am down to the last few, if I have ten pills left today and I know I am not getting paid for three weeks, I’ll take one every other day. I’ll stretch it out till I get money.[P/7]

… Last month I could not afford [drug name] at the end of the month. So, I took my other pills, some of my three months pills I took a couple of days, so I could afford the [drug name]. Now, right at this moment, I am short again until my husband has the money coming in. Right now, I am taking one of one pill today, and one of the other tomorrow to get me through till the weekend.[P/3]

… The recession hit, I was the last one hired, and first to go … For the next five years, I was doing temporary jobs. There were no benefits and I was paying out of pocket. That is when I started cutting back on the medication because I couldn’t afford to take it a hundred percent. It didn’t matter if I missed a needle. I thought I was going to die if I missed a needle. Turns out I was not, and I didn’t feel any difference. I thought if I missed two needles, then I would be affected. And like that, I missed three and four … I was taking medications for only 50 to 30 percent of the time. I was taking one needle a week, instead of every day.[P/4]

3.1.5. Selling Assets or Borrowing Money

I have considered selling my house and going to an apartment. I have considered selling my car and getting something cheaper.[P/5]

We got a huge line of credit on the house. We went into debt. We re-mortgaged the house and seriously considered selling the house. We just kept forking out this money and kept hoping we would win the lottery or something.[P/4]

I am the lucky one. I get support on top of ODSP because my family can give me some money. It is an unpeaceful relationship. I don’t want to keep that relationship, but I have to because it is the only way I can survive on income that I get from ODSP.[P/1]

3.2. Factors Affecting Decisions

3.2.1. Cost and Perceived Importance of Medications

I usually continue the three months one, because it’s cheap. The other one I cut off, because its, you know, sixty-seven dollars a month. I’ll stretch out the other one.[P/3]

Given the choice of taking [drug name] and go to sleep, which is like a dollar, versus this other stuff which is $75 a bottle, I have to go with the highly dependent and habit-forming drug, unfortunately.[P/8]

It [drug name] certainly cannot be used interchangeably for the heart or blood thinning either. But I make sure I cover that. I have to cover. That means if I have to do without something else ... I have to do without something else.[P/1]

I am trying to decide what I can cut back. I am not really sure which one was good, because its trial-and-error. You try it, but you are not really sure if it is helping at all.[P/5]

3.2.2. Financial Status and Availability of Resources

Then I was not a student, and so I had no coverage. I was self-employed. My insurance was $100 a month. As a self-employed person, I could not afford that. It really was a double-edged sword.[P/8]

There is a bunch of medicines I was taking over the years, which I could afford because the business was doing well. But because I have a fixed income and I am a single mom, I am going to have to cut back …[P/5]

I was covered by the Manitoba Automobile Insurance till it ran out. It was a $200,000 fund. I have used it up over the thirty years. It ran out about three or four years ago. Now I pay for all of that [medications and other disability-related expenses] out of pocket.[P/6]

3.2.3. Competing Demands on Resources for Self and Others

I have to pay the bills first, otherwise, I don’t have a place to live! (laughs) For little things like medications, even though I need it, I workaround.[P/3]

I have shared custody over our son … I eat a lot of peanut butter when he is not around. I put my own needs aside so that I can look after my son.[P/7]

I have a cleaner and somebody to mow my lawn … somebody to help with my groceries… those things have fallen off. All the complementary medicines have all been cut off.[P/5]

I would definitely choose his health over my health … I needed to cut back on some of my alternative medication so that I could buy him hockey equipment.[P/2]

3.2.4. Relationship and Advice from Prescribing Doctors

They [my doctors] try to adapt and try to get something else … they try to get special coverage ... I had doctors who would write several letters to make that special request … most times it is turned down by the government ... in the end, I will do without ... but doctors have been pretty good.[P/1]

I don’t get the opportunity to discuss anything with him [neurologist], because he just does his neurological examination and then I am dismissed. There is no opportunity for discussion.[P/11]

I am at a teaching facility and every time I go, it is a different resident. I don’t find anybody who knows my file and I find educating them each time difficult. Sometimes that falls through the crack.[P/12]

3.3. Impact

3.3.1. Decline in Quality of Life

I haven’t bought new clothes in a few years. In terms of grocery shopping … I get by with anything in the freezer or in the cupboard.[P/7]

I don’t do any recreational stuff. I don’t go out much either. I am still paying a mortgage, unfortunately, property taxes and all that great stuff. My whole cheque is eaten up… you could say I am living cheque to cheque.[P/9]

3.3.2. Exacerbation of Symptoms

When I skim the [drug name 1], I notice the depression increases, and if I skim the [drug name 2], then my pain symptoms increase. They are progressing, and if I don’t take [drug name 2], then the symptoms would get much worse, which would then stress me out even more.[P/7]

I haven’t had it for four weeks, because it wasn’t in my budget this month. I thought I would be okay, but I am not. I can see that I have white patches under my eyes, and I am bruising easily. Just four weeks off it, and I can see I am pale.[P/9]

A while ago, I wasn’t able to get my [drug name], as it cost $90 a package, which was way beyond my coverage … I did stop for a long time, as I could not afford it. It’s an obscene cost. Now, I am able to identify the symptoms and know what is going on … I have a lot of flare-ups, to the point that it covers a lot of my face. It’s very painful, and it brings on a Staph infection and that brings on a Strep infection, like flu. It can be very aggressive and painful.[P/8]

3.3.3. Psychological Stress

The psychological stress of it all is the biggest burden. It’s so not measurable, and it’s there every day. What are you going to buy? Where are you going to cut back? What do you need to buy for the future? Like, the wheelchair, I think what do I need to cut back to afford that? That is a lot of pressure.[P/12]

I didn’t have any [financial] support. I lost sleep, which causes immuno-deficiency, which causes stress, which causes cold sores, which causes loss of sleep. It was just a cycle.[P/10]

I had to ask my parents for my meds, and it’s very, very humiliating and embarrassing. They are 90 and 91. Fortunately, they have been able to help me out but it causes a strain on them. I don’t like to do it, unless I absolutely have to.[P/7]

3.3.4. Increased Healthcare Utilization

When I was in the hospital, I was on an antibiotic for a bone infection … I was allergic to the IV, so I had to take a pill … that pill was 1000 dollars a day and only covered if you are in the hospital ... They wanted to release me from the hospital, but I had another four days to take the pill ... so I had to stay at the hospital for an extra four days … to get the 1000 dollar pill …[P/2]

I met a doctor in [city] who decides to send me to [name] hospital in [city]. This hospital … what it does is it used a freezing element to freeze my nerves at the back and my neck to relieve some of my pain. It did help to some degree. But that meant every single week I am on the bus staying at a hotel for one night. Incredibly costly to the healthcare system[P/1]

If a person is not able to access nutrition, they will use the healthcare system more, and that is costly for the government ... same for the provincial government, if the ODSP is cut, then people will need ADP [assistive devices program] more. If it doesn’t come out from one pocket, it will come out of another.[P/10]

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy Implications

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| You indicated in your survey that you sometimes have trouble paying for your medications, and that you even sometimes don’t take your medications as prescribed because of the cost. In this interview, I’d like to ask you more about that. |

| 1. How often does this happen? When is the last time it happened? |

| 2. Does it happen more often with some medications than with others? |

| 3. How do you decide what to take and what not to take, or how to adjust your dosage to save money? |

| 4. Do you tell your doctor when you are doing this? Do you and he/she discuss the cost of the medications prescribed? |

| 5. What do you do to manage or cope with medication cost burden? |

| 6. What about other supplies and non-prescription medications—do you ever economize on those? |

| 7. What is your priority for spending on things for your or your family’s health? |

| 8. How do you think your health has been affected by not taking your pills as prescribed, or by other compromises you have had to make because of costs? |

| Strategies | Factors Affecting Decisions | Impact of Rationing Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Strategies that participants adopted to cope with medication cost burden | Factors that influence participants’ decisions to adopt rationing strategies | Consequences of forgoing medications due to cost or financial stress caused due to medications 7 |

| 1. Trying to access public or employer-based drug benefits | 1. Cost and perceived importance of medications | 1. Decline in quality of life |

| statements when participants tried to go back to work, access public drug benefits, or other social assistance to manage medication cost burden | statements where participants decided to choose to stop or continue taking a medication due to its cost and on their perceived importance or severity of their health condition or a health situation for which they were prescribed medication | statements when participants indicated that medication related financial burden reduced their general well-being or life satisfaction for them or their family members |

| 2. Seeking help from prescribing doctors | 2. Financial status and availability of resources | 2. Exacerbation of symptoms |

| statements where participants shared that they requested their doctors or pharmacist for less expensive substitutes such as generics or over-the-counter medications | statements when participants stopped or rationed on medications depending on their financial status or availability of financial resources at that particular time | statements when participants indicated that rationing on medications due to cost has led to increase or worsening of their symptoms or experienced pain |

| 3. Economizing on general or healthcare needs | 3. Competing demands on resources for self and others | 3. Psychological stress |

| statements where participants shared that they cut back on other healthcare supplies or needs such as assistive devices, or general needs such as food, clothing, car, or leisure-related activities to manage medication cost burden | statements that reflected that participants made decisions to stop or ration on medications based on their priorities for their children, other significant health needs or basic life needs | statements when participants indicated that medication related financial burden caused mental or psychological stress |

| 4. Rationing medications | 4. Relationship and advice from prescribing doctors | 4. Increased healthcare utilization |

| statements where participants shared that they decided to stop a medication temporarily or for a long duration, or taking smaller or less frequent doses, or postponed refill of a medication due to high cost | statements when participants stopped or rationed on medications in consultation with their doctors or lack thereof | statements when participants indicated that rationing on medications due to cost has led to increase in use of other health services such as more doctor visits, or even hospitalization |

| 5. Selling assets or borrowing money | ||

| statements that reflected participants tried to sell their assets or borrowed money to manage financial burden due to medications and other healthcare costs |

References

- Mitra, S.; Palmer, M.; Kim, H.; Mont, D.; Groce, N. Extra costs of living with a disability: A review and agenda for research. Disabil. Health J. 2017, 10, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; McColl, M.A.; Smith, K.; Guilcher, S.J.T. An adapted model to understand cost-related non-adherence to medications among people with disabilities. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piette, J.D.; Heisler, M.; Horne, R.; Caleb Alexander, G. A conceptually based approach to understanding chronically ill patients’ responses to medication cost pressures. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Mccoll, M.A.; Guilcher, S.J.T.; Smith, K. Cost-related nonadherence to prescription medications in Canada: A Scoping Review. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 12, 1699–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabaté, E.; World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.; Newman, J.F. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem. Fund Q. Health Soc. 1973, 51, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.R.; Cheng, L.; Kolhatkar, A.; Goldsmith, L.J.; Morgan, S.G.; Holbrook, A.M.; Dhalla, I.A. The consequences of patient charges for prescription drugs in Canada: A cross-sectional survey. CMAJ Open 2018, 6, E63–E70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Commonwealth Fund. International Health Policy Survey of Adults. In International Health Policy Surveys; The Commonwealth Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kratzer, J.; Cheng, L.; Allin, S.; Law, M.R. The Impact of Private Insurance Coverage on Prescription Drug Use in Ontario, Canada. Healthc. Policy 2015, 10, 62–74. Available online: http://www.longwoods.com/content/24212 (accessed on 22 August 2019). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daw, J.R.; Morgan, S.G. Stitching the gaps in the Canadian public drug coverage patchwork? A review of provincial pharmacare policy changes from 2000 to 2010. Health Policy 2012, 104, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanley, G.E.; Morgan, S. Chronic catastrophes: Exploring the concentration and sustained nature of ambulatory prescription drug expenditures in the population of British Columbia, Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.L.; Ghali, W.A.; Manns, B.J. Addressing cost-related barriers to prescription drug use in Canada. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2014, 186, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewa, C.S.; Hoch, J.S.; Steele, L. Prescription drug benefits and Canada’s uninsured. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2005, 28, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stats Canada. Canadian Survey on Disability: A Demographic, Employment and Income Profile of Canadians with Disabilities Aged 15 Years and Over, 2017; Stats Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-654-x/89-654-x2018002-eng.htm (accessed on 22 August 2019).

- Farry, A.; Baxter, D. The Incidence and Prevalence of Spinal Cord Injury in CANADA: Overview and Estimates Based on Current Evidence; Rick Hansen Institute & Urban Futures: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, H.; Noonan, V.K.; Trenaman, L.M.; Joshi, P.; Rivers, C.S. The economic burden of traumatic spinal cord injury in Canada. Chronic Dis. Inj. Can. 2013, 33, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guilcher, S.J.T.; Hogan, M.; Calzavara, A.; Hitzig, S.L.; Patel, T.; Packer, T.; Lofters, A.K. Prescription drug claims following a traumatic spinal cord injury for older adults: A retrospective population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Spinal Cord 2018, 56, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzman, P.; Cecil, D.; Kolpek, J.H. The risks of polypharmacy following spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2017, 40, 147–153. Available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1179/2045772314Y.0000000235 (accessed on 22 August 2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rick Hansen Institute. A Look at Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury in Canada: Rick Hansen Spinal Cord Registry (RHSCIR). J. Spinal Cord Med. 2017, 40, 870–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; McColl, M.A.; Guilcher, S.J.; Smith, K. Cost-related nonadherence to medications: Evidence from people with spinal cord injuries in Canada. Disabil. Health 2019. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.M.; Namey, E.E. Applied Thematic Analysis; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. NVivo 11 Pro for Windows. 2019. Available online: http://www.qsrinternational.com/ nvivo/nvivo-products/nvivo-11-for-windows/nvivo-pro (accessed on 22 August 2019).

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoe, J.E.; Baez, A.; Angier, H.; Krois, L.; Edlund, C.; Carney, P.A. Insurance + access not equal to health care: Typology of barriers to health care access for low-income families. Ann. Fam. Med. 2007, 5, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, L.J.; Kolhatkar, A.; Popowich, D.; Holbrook, A.M.; Morgan, S.G.; Law, M.R. Understanding the patient experience of cost-related non-adherence to prescription medications through typology development and application. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 194, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwlaat, R.; Wilczynski, N.; Navarro, T.; Hobson, N.; Jeffery, R.; Keepanasseril, A.; Agoritsas, T.; Mistry, N.; Iorio, A.; Jack, S.; et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, CD000011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberta College of Family Physicians. Price Comparison of Commonly Prescribed Pharmaceuticals in Alberta 2018; Alberta College of Family Physicians: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Demain, S.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Areia, C.; Oliveira, R.; Marcos, A.J.; Marques, A.; Parmar, R.; Hunt, K. Living with, managing and minimising treatment burden in long term conditions: A systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosbach, M.; Andersen, J.S. Patient-experienced burden of treatment in patients with multimorbidity-A systematic review of qualitative data. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sav, A.; Kendall, E.; McMillan, S.S.; Kelly, F.; Whitty, J.A.; King, M.A.; Wheeler, A.J. ‘You say treatment, I say hard work’: Treatment burden among people with chronic illness and their carers in Australia. Health Soc. Care Community 2013, 21, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilcher, S.J.T.; Munce, S.E.P.; Conklin, J.; Packer, T.; Verrier, M.; Marras, C.; Bereket, T.; Versnel, J.; Riopelle, R.; Jaglal, S. The Financial Burden of Prescription Drugs for Neurological Conditions in Canada: Results from the National Population Health Study of Neurological Conditions. Health Policy 2017, 121, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Lemmens, T.; Persaud, N. Medication access via hospital admission. Can. Fam. Physician 2017, 63, 344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Towards Implementation of National Pharmacare. 2018. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/corporate/publications/council_on_pharmacare_EN.PDF (accessed on 22 August 2019).

- Novick, G. Is there a bias against telephone interviews in qualitative research? Res. Nurs. Health 2008, 31, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Participant Characteristics | n/Median (q1, q3) * |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.5 (46, 58.25) |

| Females | 8 |

| Relationship status | |

| ● Married or in a relationship | 5 |

| ● Single, divorced or never married | 7 |

| Education | |

| ● Up to high school | 2 |

| ● College degree or certificate | 7 |

| ● University degree and above | 3 |

| Work status | |

| ● Employed | 2 |

| ● Retired | 1 |

| ● On disability income | 8 |

| ● Unpaid disability and unemployed | 1 |

| SCI-related characteristics | |

| ● Traumatic | 6 |

| ● Paraplegia | 9 |

| ● Incomplete | 6 |

| ● Time since injury (years) | 20 (10, 28.5) |

| Number of medications 1 (median) | 9.5 (5, 13) |

| Monthly out of pocket cost of medications 1 (CAD) | 316.5 (181.25, 398.75) |

| Type of insurance 2 | |

| ● Public drug benefit program | 8 |

| ● Employer based insurance | 4 |

| ● Family based insurance | 1 |

| ● Other | 1 |

| ● No insurance | 2 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gupta, S.; McColl, M.A.; Guilcher, S.J.T.; Smith, K. Managing Medication Cost Burden: A Qualitative Study Exploring Experiences of People with Disabilities in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173066

Gupta S, McColl MA, Guilcher SJT, Smith K. Managing Medication Cost Burden: A Qualitative Study Exploring Experiences of People with Disabilities in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(17):3066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173066

Chicago/Turabian StyleGupta, Shikha, Mary Ann McColl, Sara J.T. Guilcher, and Karen Smith. 2019. "Managing Medication Cost Burden: A Qualitative Study Exploring Experiences of People with Disabilities in Canada" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 17: 3066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173066

APA StyleGupta, S., McColl, M. A., Guilcher, S. J. T., & Smith, K. (2019). Managing Medication Cost Burden: A Qualitative Study Exploring Experiences of People with Disabilities in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(17), 3066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173066