Physiological Characterization of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius in a Controlled Bioreactor Environment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bioreactor Cultivations

2.2. Biomass Determination

2.3. Substrate and Metabolites Analytics

2.4. Calculation of Rates, Substrate Affinity Constants and Maintenance Coefficient

3. Results

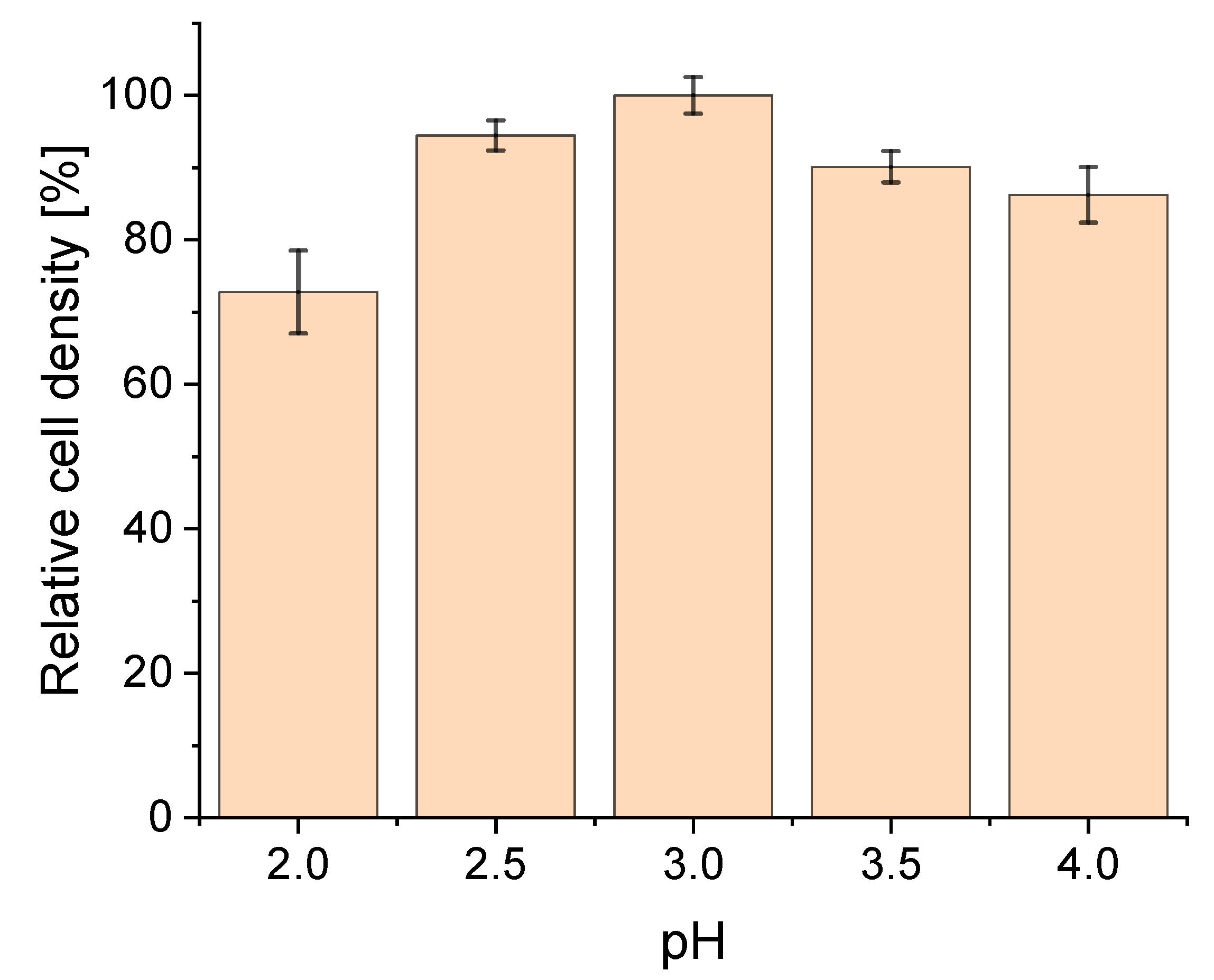

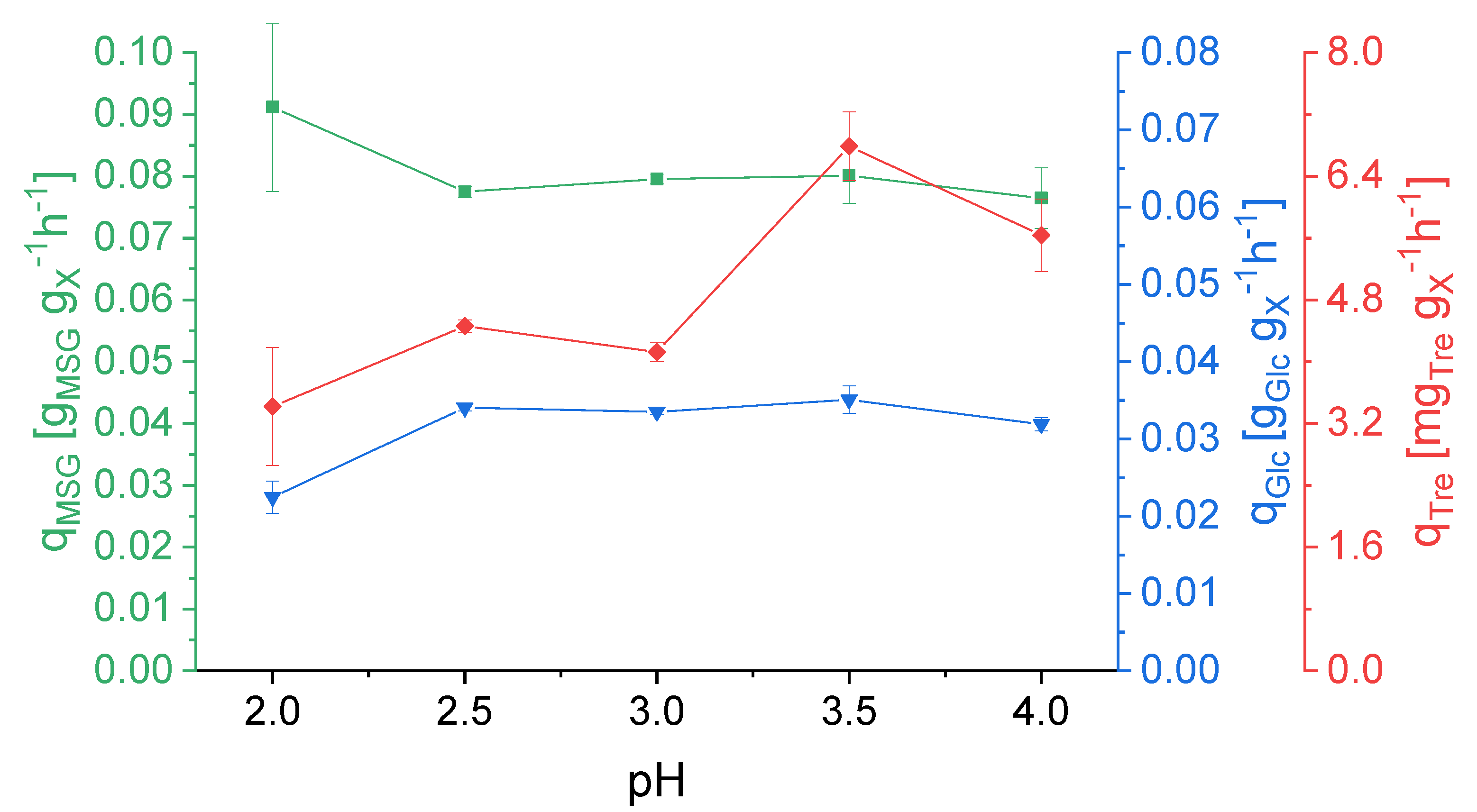

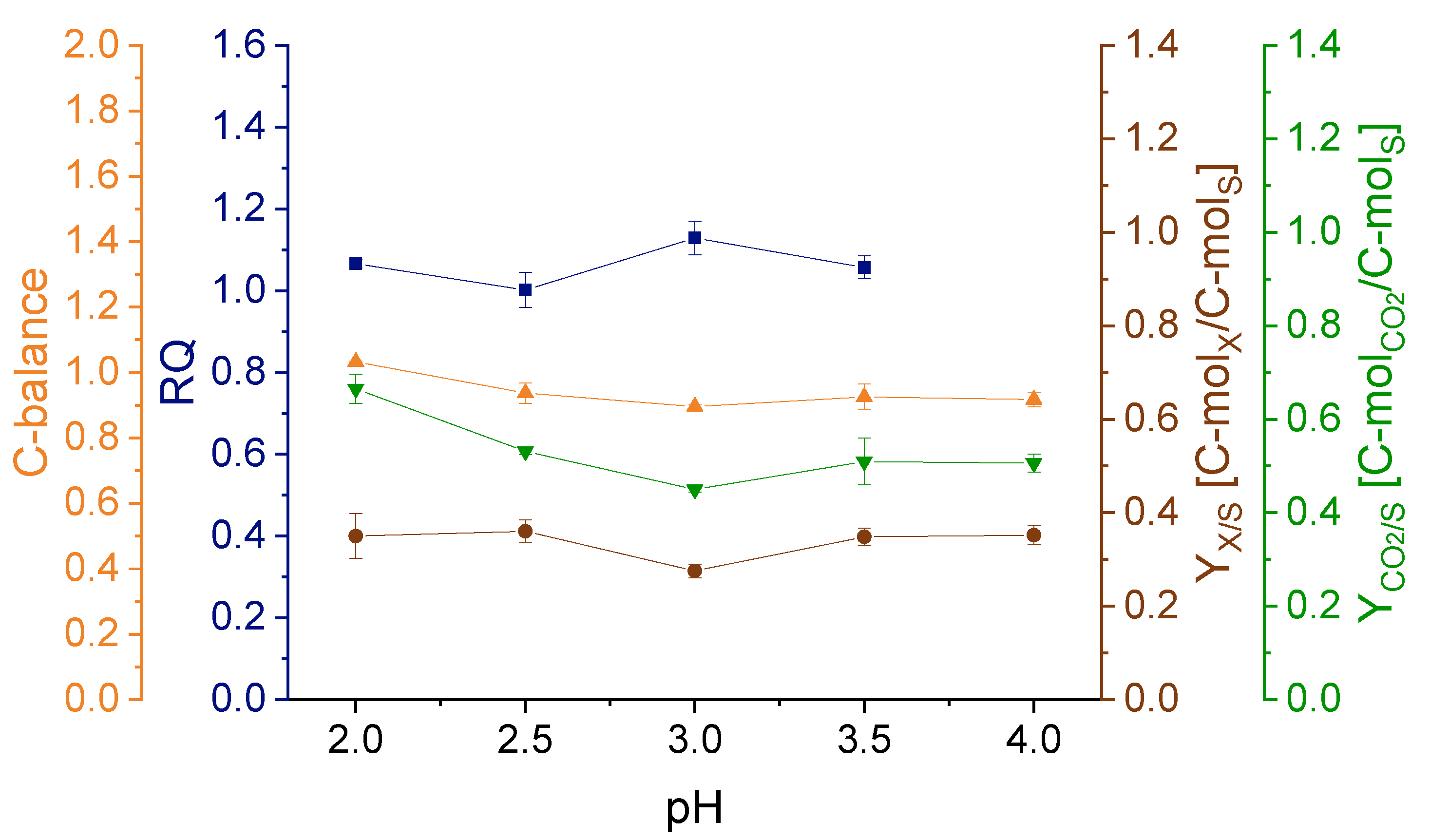

3.1. Effect of pH on Strain Physiology

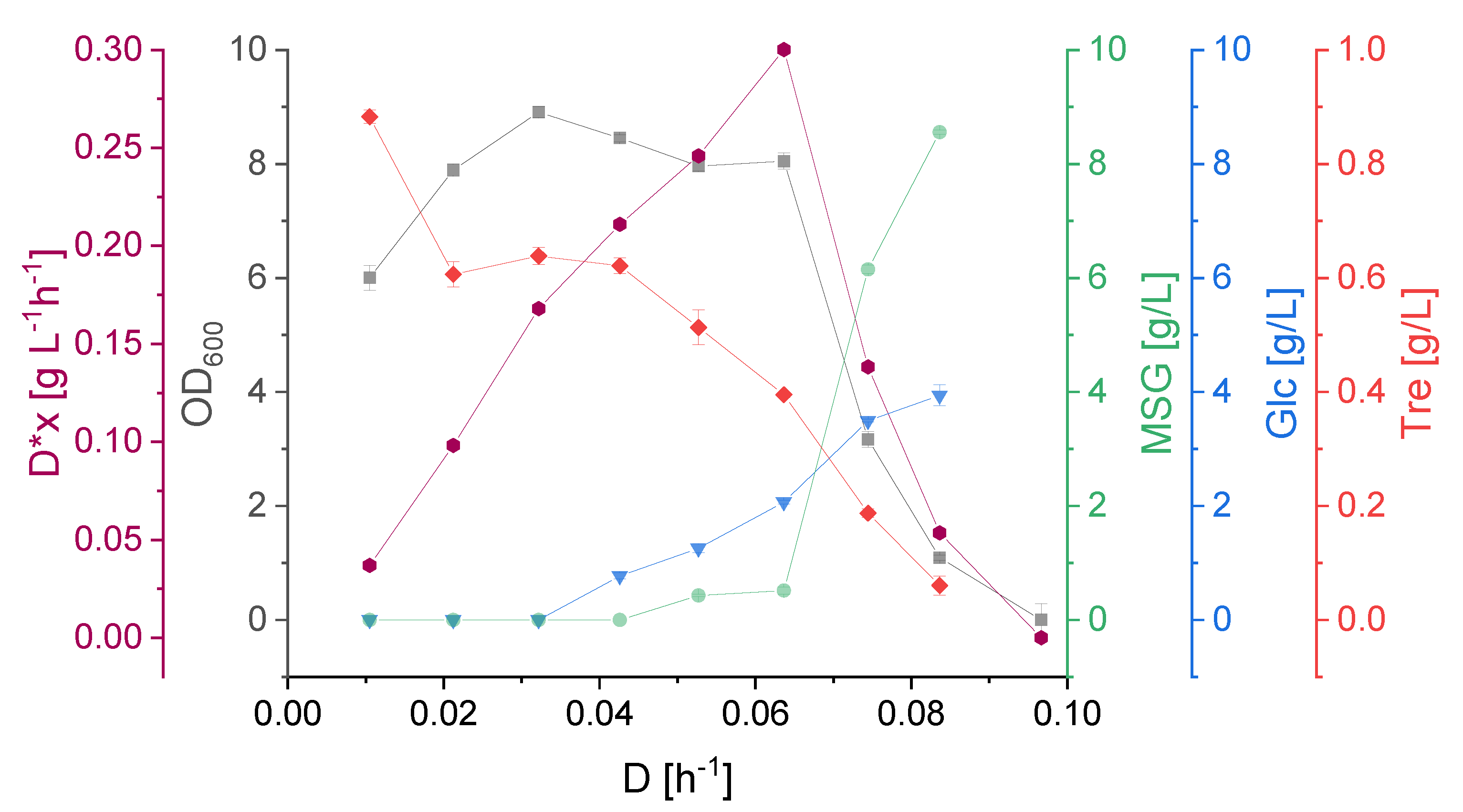

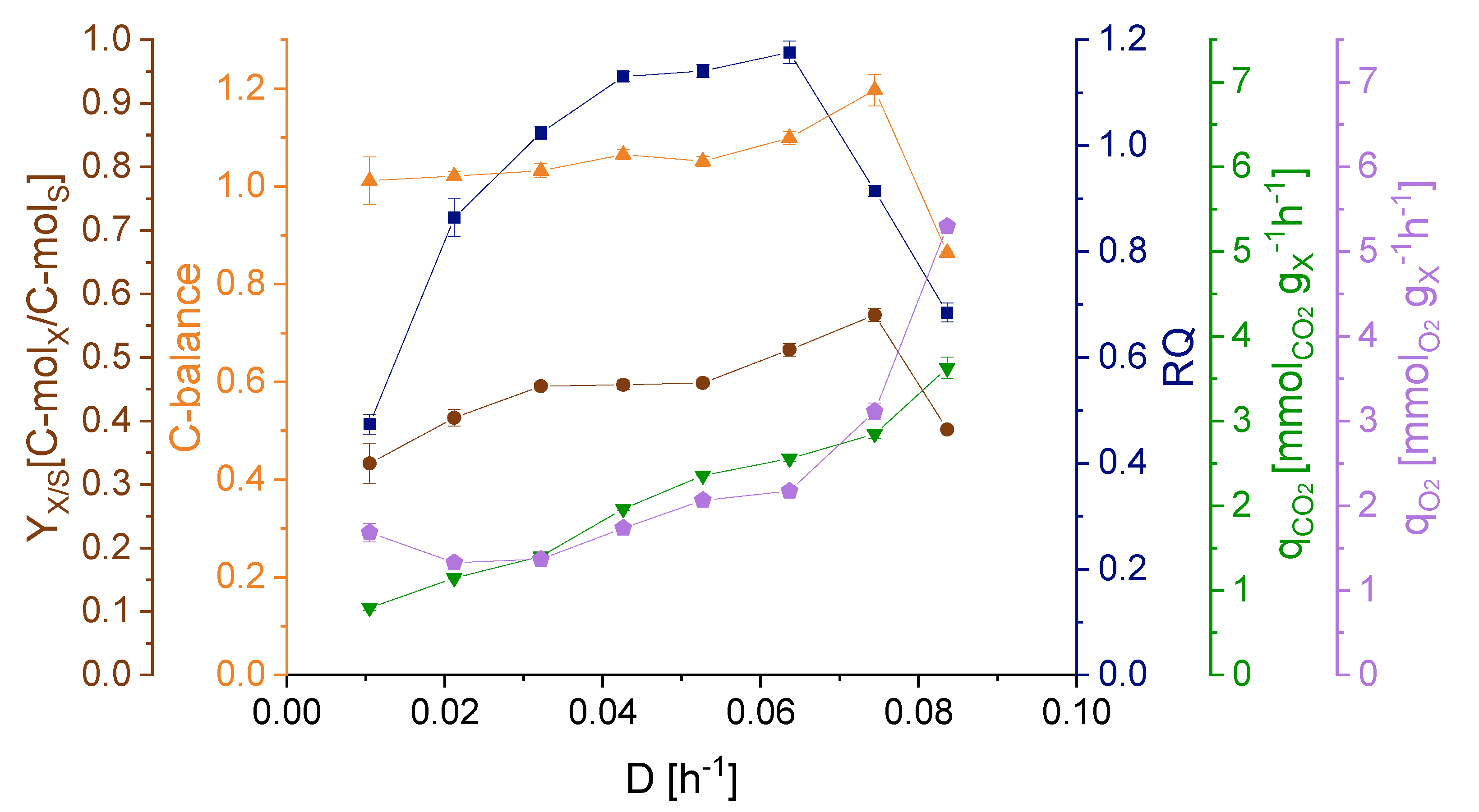

3.2. Effect of Dilution Rate on Strain Physiology

3.3. KS Values, Optimal and Critical Dilution Rate

3.4. Maintenance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, L.; Brügger, K.; Skovgaard, M.; Redder, P.; She, Q.; Torarinsson, E.; Greve, B.; Awayez, M.; Zibat, A.; Klenk, H.-P.; et al. The Genome of Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius, a Model Organism of the Crenarchaeota. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 4992–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wagner, M.; van Wolferen, M.; Wagner, A.; Lassak, K.; Meyer, B.H.; Reimann, J.; Albers, S.-V. Versatile Genetic Tool Box for the Crenarchaeote Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gudbergsdottir, S.; Deng, L.; Chen, Z.; Jensen, J.V.K.; Jensen, L.R.; She, Q.; Garrett, R.A. Dynamic Properties of the Sulfolobus CRISPR/Cas and CRISPR/Cmr Systems When Challenged with Vector-Borne Viral and Plasmid Genes and Protospacers. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 79, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grogan, D.W. Phenotypic Characterization of the Archaebacterial Genus Sulfolobus: Comparison of Five Wild-Type Strains. J Bacteriol. 1989, 171, 6710–6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, A.; Weber, Y.; Chiu, B.K.; Elling, F.J.; Cobban, A.B.; Pearson, A.; Leavitt, W.D. Energy Flux Controls Tetraether Lipid Cyclization in Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buetti-Dinh, A.; Dethlefsen, O.; Friedman, R.; Dopson, M. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals How a Lack of Potassium Ions Increases Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius Sensitivity to PH Changes. Microbiology 2016, 162, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quehenberger, J.; Pittenauer, E.; Allmaier, G.; Spadiut, O. The Influence of the Specific Growth Rate on the Lipid Composition of Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius. Extremophiles 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zeng, Z.; Liu, X.-L.; Wei, J.H.; Summons, R.E.; Welander, P.V. Calditol-Linked Membrane Lipids Are Required for Acid Tolerance in Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bischof, L.F.; Haurat, M.F.; Hoffmann, L.; Albersmeier, A.; Wolf, J.; Neu, A.; Pham, T.K.; Albaum, S.A.; Jakobi, T.; Schouten, S.; et al. Early Response of Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius to Nutrient Limitation. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Delago, A.; Nußbaum, P.; Meyer, B.; Albers, S.-V.; Eichler, J. Gene Deletions Leading to a Reduction in the Number of Cyclopentane Rings in Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius Tetraether Lipids. Fems Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobban, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, A.; Weber, Y.; Elling, F.J.; Pearson, A.; Leavitt, W.D. Multiple Environmental Parameters Impact Lipid Cyclization in Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 4046–4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Ochoa, F.; Santos, V.E.; Gomez, E. 2.15-Stirred Tank Bioreactors. In Comprehensive Biotechnology, 2nd ed.; Moo-Young, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Burlington, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 179–198. ISBN 978-0-08-088504-9. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, T.D.; Mosser, J.L. Rate of Sulfuric-Acid Production in Yellowstone National Park. Gsa Bull. 1975, 86, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangler, L.E.; Susong, D.D. Use of Dye Tracing to Determine Ground-Water Movement to Mammoth Crystal Springs, Sylvan Pass Area, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming; Scientific Investigations Report; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2006; Volume 2006–5126, p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, N.; Larson, P.; Fairley, J.; Mulvaney-Norris, J.; Lindsey, C.R. Direct Measurement of Advective Heat Flux from Several Yellowstone Hot Springs, Wyoming, USA. Geosphere 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žnidaršič-Plazl, P.; Plazl, I. 2.21-Microbioreactors. In Comprehensive Biotechnology, 2nd ed.; Moo-Young, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Burlington, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 289–301. ISBN 978-0-08-088504-9. [Google Scholar]

- Weusthuis, R.A.; Pronk, J.T.; van den Broek, P.J.; van Dijken, J.P. Chemostat Cultivation as a Tool for Studies on Sugar Transport in Yeasts. Microbiol Rev 1994, 58, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunham, M.J.; Kerr, E.O.; Miller, A.W.; Payen, C. Chemostat Culture for Yeast Physiology and Experimental Evolution. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, H.; Bennett, G.N.; San, K.-Y. Chemostat Culture Characterization of Escherichia Coli Mutant Strains Metabolically Engineered for Aerobic Succinate Production: A Study of the Modified Metabolic Network Based on Metabolite Profile, Enzyme Activity, and Gene Expression Profile. Metab. Eng. 2005, 7, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, H.; Kerndt, C.C.; Bhardwaj, A. Physiology, Respiratory Quotient. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Elbein, A.D.; Pan, Y.T.; Pastuszak, I.; Carroll, D. New Insights on Trehalose: A Multifunctional Molecule. Glycobiology 2003, 13, 17R–27R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quehenberger, J.; Albersmeier, A.; Glatzel, H.; Hackl, M.; Kalinowski, J.; Spadiut, O. A Defined Cultivation Medium for Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 301, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, C.; Meyer, B.H.; Hagemann, A.; Jo, E.; Lee, A.; Albers, S.-V.; Cha, J.; Bräsen, C.; Siebers, B. Salt Stress Response of Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius Involves Complex Trehalose Metabolism Utilizing a Novel Trehalose-6-Phosphate Synthase (TPS)/Trehalose-6-Phosphate Phosphatase (TPP) Pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemuri, G.N.; Altman, E.; Sangurdekar, D.P.; Khodursky, A.B.; Eiteman, M.A. Overflow Metabolism in Escherichia Coli during Steady-State Growth: Transcriptional Regulation and Effect of the Redox Ratio. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 3653–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valgepea, K.; Adamberg, K.; Nahku, R.; Lahtvee, P.-J.; Arike, L.; Vilu, R. Systems Biology Approach Reveals That Overflow Metabolism of Acetate in Escherichia Coli Is Triggered by Carbon Catabolite Repression of Acetyl-CoA Synthetase. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010, 4, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valentine, D.L. Adaptations to Energy Stress Dictate the Ecology and Evolution of the Archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brock, T.D.; Brock, K.M.; Belly, R.T.; Weiss, R.L. Sulfolobus: A New Genus of Sulfur-Oxidizing Bacteria Living at Low PH and High Temperature. Arch. Mikrobiol. 1972, 84, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granata, V.; Graziano, G.; Ruggiero, A.; Raimo, G.; Masullo, M.; Arcari, P.; Vitagliano, L.; Zagari, A. Stability against Temperature of Sulfolobus Solfataricus Elongation Factor 1α, a Multi-Domain Protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (Bba) Proteins Proteom. 2008, 1784, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korz, D.J.; Rinas, U.; Hellmuth, K.; Sanders, E.A.; Deckwer, W.-D. Simple Fed-Batch Technique for High Cell Density Cultivation of Escherichia Coli. J. Biotechnol. 1995, 39, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiloach, J.; Fass, R. Growing E. Coli to High Cell Density—A Historical Perspective on Method Development. Biotechnol. Adv. 2005, 23, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Tevatia, R.; White, D.; Demirel, Y.; Blum, P. Comparative Kinetic Modeling of Growth and Molecular Hydrogen Overproduction by Engineered Strains of Thermotoga Maritima. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 7125–7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pirt, S.J. The Maintenance Energy of Bacteria in Growing Cultures. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1965, 163, 224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Vetter, A.M.; Helmecke, J.; Schomburg, D.; Neumann-Schaal, M. The Impact of Pyroglutamate: Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius Has a Growth Advantage over Saccharolobus Solfataricus in Glutamate-Containing Media. Archaea 2019, 2019, 3208051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koerdt, A.; Gödeke, J.; Berger, J.; Thormann, K.M.; Albers, S.-V. Crenarchaeal Biofilm Formation under Extreme Conditions. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, S.-V.; Koning, S.; Konings, W.; Driessen, A. Insights into ABC Transport in Archaea. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2004, 36, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wagner, M.; Shen, L.; Albersmeier, A.; van der Kolk, N.; Kim, S.; Cha, J.; Bräsen, C.; Kalinowski, J.; Siebers, B.; Albers, S.-V. Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius Transports Pentoses via a Carbohydrate Uptake Transporter 2 (CUT2)-Type ABC Transporter and Metabolizes Them through the Aldolase-Independent Weimberg Pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cooper, G.M. Transport of Small Molecules. In The Cell: A Molecular Approach, 2nd ed.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, S.; Johnson, T.; Pavlik, B.L.; Payne, S.; Schackwitz, W.; Martin, J.; Lipzen, A.; Keffeler, E.; Blum, P. Expanding the Limits of Thermoacidophily in the Archaeon Sulfolobus Solfataricus by Adaptive Evolution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Fixed Parameter | Variable Parameter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| D | 0.03 h−1 | pH | 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0 |

| pH | 3.0 | D | 0.010 h−1, 0.021 h−1, 0.032 h−1, 0.043 h−1, 0.053 h−1, 0.064 h−1, 0.074 h−1, 0.084 h−1, 0.097 h−1 |

| Parameters | D-Glucose | Monosodium Glutamate (MSG) |

|---|---|---|

| µmax [h−1] | 0.095 ± 0.004 | 0.077 ± 0.003 |

| KS [g/L] | 0.99 ± 0.13 | 0.15 ± 0.04 |

| Dopt [h−1] | 0.055 | 0.068 |

| Dcrit [h−1] | 0.078 | 0.077 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rastädter, K.; Wurm, D.J.; Spadiut, O.; Quehenberger, J. Physiological Characterization of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius in a Controlled Bioreactor Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115532

Rastädter K, Wurm DJ, Spadiut O, Quehenberger J. Physiological Characterization of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius in a Controlled Bioreactor Environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(11):5532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115532

Chicago/Turabian StyleRastädter, Kerstin, David Johannes Wurm, Oliver Spadiut, and Julian Quehenberger. 2021. "Physiological Characterization of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius in a Controlled Bioreactor Environment" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 11: 5532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115532

APA StyleRastädter, K., Wurm, D. J., Spadiut, O., & Quehenberger, J. (2021). Physiological Characterization of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius in a Controlled Bioreactor Environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115532