Exploring the Engaged Worker over Time—A Week-Level Study of How Positive and Negative Work Events Affect Work Engagement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. What Happens in the Short Run: Work Events as Antecedents of Work Engagement

1.2. Temporal Patterns of Positive Events

1.3. Temporal Patterns of Negative Events

1.4. The Interplay of Positive and Negative Events over Time

1.5. What Happens in the Long Run: Sustained Effects of Work Events over Time

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Positive Work and Negative Work Events during the Workweek

2.3.2. Work Engagement during the Workweek

2.4. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Short-Term Effects of Work Events

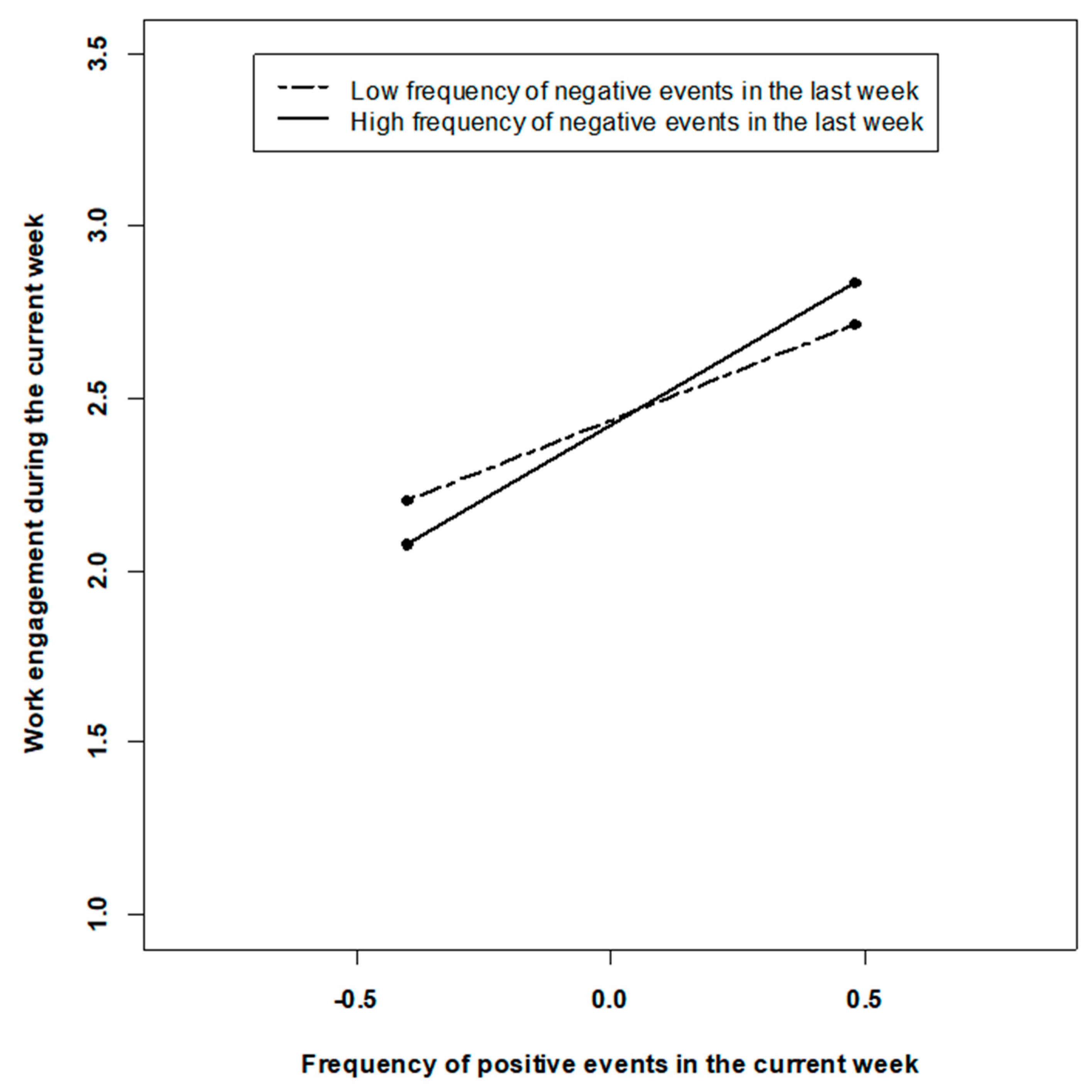

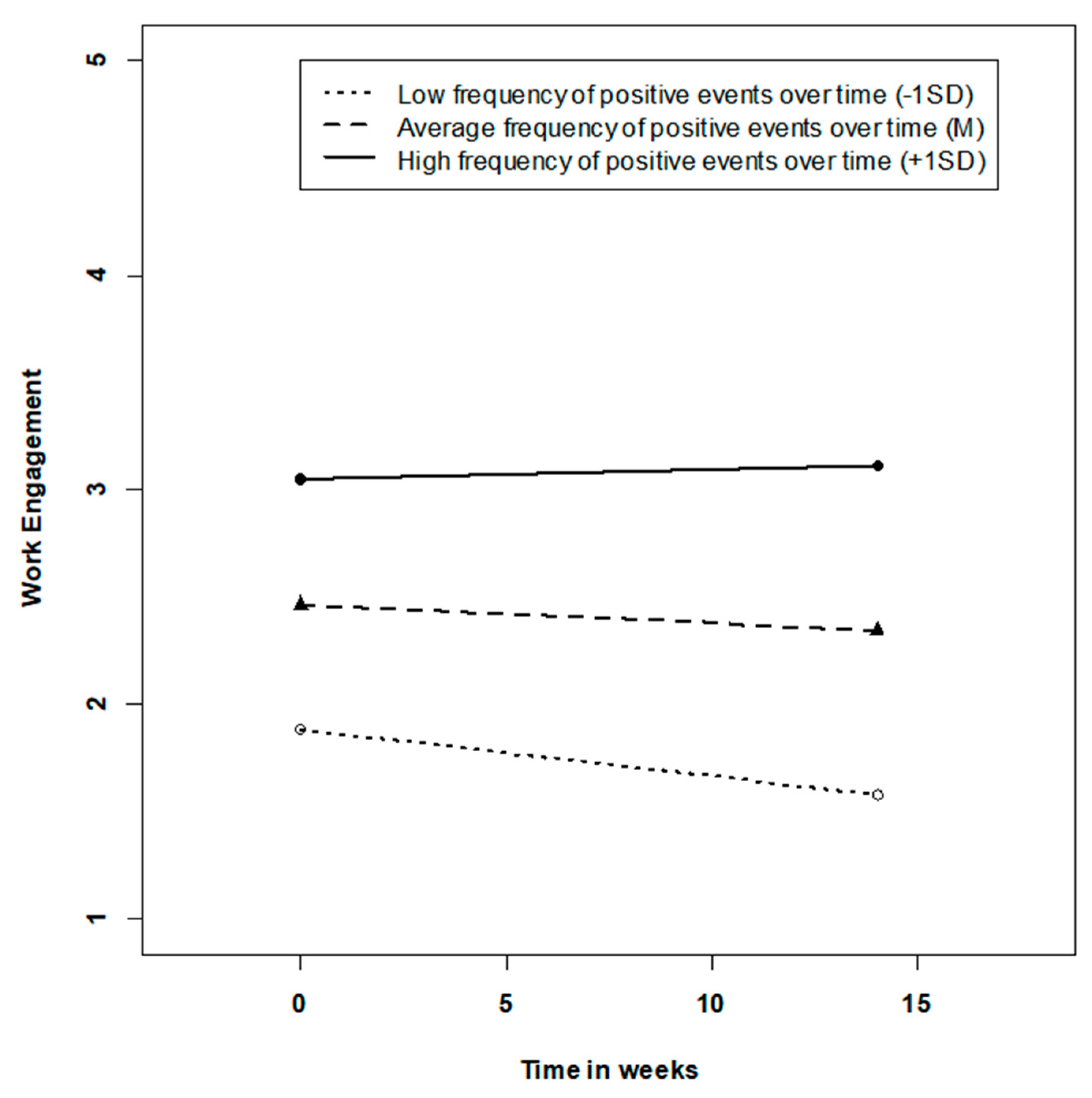

3.2. Mid-Term Changes in Work Engagement Due to Work Events

3.3. Additional Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morgeson, F.P.; Mitchell, T.R.; Liu, D. Event system theory: An event-oriented approach to the organizational sciences. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- George, J.M.; Jones, G.R. The role of time in theory and theory building. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 657–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.R.; James, L.R. Building better theory: Time and the specification of when things happen. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 530–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonnentag, S. Time in organizational research: Catching up on a long neglected topic in order to improve theory. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 2, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Bakker, R.M. Time is of the essence: Improving the conceptualization and measurement of time. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2021, 31, 100763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, S.; Schmitt, A. What makes us enthusiastic, angry, feeling at rest or worried? Development and validation of an affective work events taxonomy using concept mapping methodology. J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 30, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B. An evidence-based model of work engagement. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crawford, E.R.; LePine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B. Daily Fluctuations in Work Engagement: An Overview and Current Directions. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective Events Theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews; Staw, B.M., Cummings, L.L., Eds.; Elsevier Science/JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1996; Volume 18, pp. 1–74. ISBN 1-55938-938-9. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, K. Rethinking job characteristics in work stress research. Hum. Relat. 2006, 59, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuba, K.; Scheibe, S. Let it be and keep on going! Acceptance and daily occupational well-being in relation to negative work events. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, R.E.; Knee, C.R. Examining temporal processes in diary studies. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 39, 1184–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, J.A.; Stanton, J.M.; Fisher, G.G.; Spitzmüller, C.; Russell, S.S.; Smith, P.C. A Lengthy Look at the Daily Grind: Time Series Analysis of Events, Mood, Stress, and Satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 1019–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Rupp, D.E. Experiencing work: An essay on a person-centric work psychology. Ind. Organ. Psychol. Perspect. Sci. Pract. 2011, 4, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledow, R.; Schmitt, A.; Frese, M.; Kühnel, J. The affective shift model of work engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gross, S.; Semmer, N.K.; Meier, L.L.; Kälin, W.; Jacobshagen, N.; Tschan, F. The effect of positive events at work on after-work fatigue: They matter most in face of adversity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ilies, R.; Aw, S.S.Y.; Pluut, H. Intraindividual models of employee well-being: What have we learned and where do we go from here? Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurs, J.A.; Perrewé, P.L. Cognitive activation theory of stress: An integrative theoretical approach to work stress. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1043–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; Glomb, T.M.; Shen, W.; Kim, E.; Koch, A.J. Building positive resources: Effects of positive events and positive reflection on work stress and health. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1601–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Neveu, J.-P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, R.R.; Sliter, M.; Mohr, C.D.; Sears, L.E.; Deese, M.N.; Wright, R.R.; Cadiz, D.; Jacobs, L. Bad versus Good, What Matters More on the Treatment Floor? Relationships of Positive and Negative Events with Nurses’ Burnout and Engagement. Res. Nurs. Health 2015, 38, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhu, J.; Dormann, C.; Song, Z.; Bakker, A.B. The daily motivators: Positive work events, psychological needs satisfaction, and work engagement. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2019, 69, 508–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, D.J.; Weiss, H.M.; Barros, E.; MacDermid, S.M. An episodic process model of affective influences on performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1054–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Cropanzano, R. The buffering role of sportsmanship on the effects of daily negative events. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zerubavel, E. The Seven Day Circle: The History and Meaning of the Week; First Prinitng edition; University Of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0-226-98165-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dormann, C.; Van de Ven, B. Timing in methods for studying psychosocial factors at work. In Psychosocial Factors at Work in the Asia Pacific; Dollard, M.F., Shimazu, A., Bin Nordin, R., Brough, P., Tuckey, M.R., Dollard, M.F., Shimazu, A., Bin Nordin, R., Brough, P., Tuckey, M.R., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 89–116. ISBN 978-94-017-8974-5. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, L.L.; Cho, E.; Dumani, S. The effect of positive work reflection during leisure time on affective well-being: Results from three diary studies. J. Organiz. Behav. 2016, 37, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Keeney, J.; Goh, Z.W. Capitalising on positive work events by sharing them at home. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2015, 64, 578–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Scollon, C.N. Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. Am. Psychol. 2006, 61, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Branigan, C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cogn. Emot. 2005, 19, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, S.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.; Salanova, M. Does a positive gain spiral of resources, efficacy beliefs and engagement exist? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solinger, O.N.; Hofmans, J.; Bal, P.M.; Jansen, P.G.W. Bouncing back from psychological contract breach: How commitment recovers over time. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 494–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gump, B.B.; Matthews, K.A. Do background stressors influence reactivity to and recovery from acute stressors?1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, A.S.; Kashdan, T.B. Stress sensitivity and stress generation in social anxiety disorder: A temporal process approach. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2015, 124, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 873–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. Eur. J. Personal. 1987, 1, 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seery, M.D.; Leo, R.J.; Lupien, S.P.; Kondrak, C.L.; Almonte, J.L. An upside to adversity? Moderate cumulative lifetime adversity is associated with resilient responses in the face of controlled stressors. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, M.; Zapf, D. Methodological issues in the study of work stress: Objective vs subjective measurement af work stress and the question of longitudinal studies. In Causes, Coping and Consequences of Stress at Work; Cooper, C.L., Payne, R., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1988; pp. 375–411. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, N.; DeLongis, A.; Kessler, R.C.; Schilling, E.A. Effects of daily stress on negative mood. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.J.; Suls, J.; Alliger, G.M.; Learner, S.M.; Wan, C.K. Multiple role juggling and daily mood states in working mothers: An experience sampling study. J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S. The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety Stress Coping: Int. J. 2008, 21, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-C.; Chen, C.-C.; Liu, H.-L. Test of a model linking employee positive moods and task performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tice, D.M.; Baumeister, R.F.; Shmueli, D.; Muraven, M. Restoring the self: Positive affect helps improve self-regulation following ego depletion. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebner, S.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. The success resource model of job stress. In New Developments in Theoretical and Conceptual Approaches to Job Stress; Perrewé, P.L., Halbesleben, J.R.B., Rose, C., Eds.; Research in Occupational Stress and Well-being; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2010; Volume 8, pp. 61–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gorgievski, M.J.; Hobfoll, S.E. Work can burn us out and fire us up. In Handbook of Stress and Burnout in Health Care; Halbesleben, J.R.B., Ed.; Nova Publishers: Hauppage, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kühnel, J.; Sonnentag, S.; Bledow, R. Resources and time pressure as day-level antecedents of work engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 85, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W. The use of causal indicators in covariance structure models: Some practical issues. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 114, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. Recovery, work engagement and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geldhof, G.J.; Preacher, K.J.; Zyphur, M.J. Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychol. Methods 2014, 19, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, F.L. Conducting Multilevel Confirmatory Factor Analysis Using R. Available online: http://faculty.missouri.edu/huangf/data/mcfa/MCFAinRHUANG.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2017).

- Hayes, A.F.; Coutts, J.J. Use Omega Rather than Cronbach’s Alpha for Estimating Reliability. But…. Commun. Methods Meas. 2020, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, C.-H. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 48, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jorgensen, T.D.; Pornprasertmanit, S.; Schoemann, A.M.; Rosseel, Y. Useful Tools for Structural Equation Modeling [R Package SemTools Version 0.5-4]; Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). 2021. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semTools (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Raudenbush, S.W. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, J.C.; Bates, D.M. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS; Statistics and Computing; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-1-4419-0317-4. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, C.K.; Tofighi, D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paccagnella, O. Centering or not centering in multilevel models? The role of the group mean and the assessment of group effects. Eval. Rev. 2006, 30, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.G.; Ryu, E.; Kwok, O.-M.; Cham, H. Multilevel modeling: Current and future applications in personality research. J. Personal. 2011, 79, 2–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Bliese, P.D.; Mathieu, J.E. Conceptual framework and statistical procedures for delineating and testing multilevel theories of homology. Organ. Res. Methods 2005, 8, 375–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kreft, I.G.G.; de Leeuw, J.; Aiken, L.S. The effect of different forms of centering in hierarchical linear models. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1995, 30, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliese, P.D.; Ployhart, R.E. Growth modeling using random coefficient models: Model building, testing and illustrations. Organ. Res. Methods 2002, 5, 362–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Curran, P.J.; Bauer, D.J. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling and latent curve analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2006, 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U.R.; Lang, J.W.B.; Depenbrock, F.; Fehrmann, C.; Zijlstra, F.R.H.; Alberts, H.J.E.M. The power of presence: The role of mindfulness at work for daily levels and change trajectories of psychological detachment and sleep quality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 1113–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Syrek, C.J.; Weigelt, O.; Peifer, C.; Antoni, C.H. Zeigarnik’s sleepless nights: How unfinished tasks at the end of the week impair employee sleep on the weekend through rumination. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoffman, E.L.; Lord, R.G. A taxonomy of event-level dimensions: Implications for understanding leadership processes, behavior, and performance. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 558–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, W.R.; Shipp, A.J.; Payne, S.C.; Culbertson, S.S. Changes in newcomer job satisfaction over time: Examining the pattern of honeymoons and hangovers. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 844–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boswell, W.R.; Boudreau, J.W.; Tichy, J. The relationship between employee job change and job satisfaction: The honeymoon-hangover effect. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. An alternative approach: The unfolding model of voluntary employee turnover. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 51–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacmar, K.M.; Witt, L.A.; Zivnuska, S.; Gully, S.M. The interactive effect of leader-member exchange and communication frequency on performance ratings. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. In Leadership: Understanding the Dynamics of Power and Influence in Organizations; Vecchio, R.P., Ed.; University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame, IN, USA, 1997; pp. 318–333. ISBN 0-268-01316-0. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M.; Fried, Y.; Juillerat, T. Work matters: Job design in classic and contemporary perspectives. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Volume 1: Building and Developing the Organization; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 417–453. ISBN 1-4338-0732-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T.R.; Thompson, L.; Peterson, E.; Cronk, R. Temporal adjustments in the evaluation of events: The “rosy view”. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 33, 421–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend? Organ. Res. Methods 2006, 9, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, A.; Tremmel, S.; Sonnentag, S. The power of affect: A three-wave panel study on reciprocal relationships between work events and affect at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 92, 430–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, C.; Griffin, M.A. Optimal Time Lags in Panel Studies. Psychol. Methods 2015, 20, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, C.C.; Oud, J.H.L.; Voelkle, M.C. Continuous time structural equation modeling with R package ctsem. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 77, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bliese, P.D.; Adler, A.B.; Flynn, P.J. Transition processes: A review and synthesis integrating methods and theory. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, J.; Lanaj, K.; Bono, J.; Campana, K. Daily shifts in regulatory focus: The influence of work events and implications for employee well-being. J. Organiz. Behav. 2016, 37, 1293–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, K.A.; Allen, T.D. Episodic work-family conflict and strain: A dynamic perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 863–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bliese, P.D.; Lang, J.W.B. Understanding relative and absolute change in discontinuous growth models: Coding alternatives and implications for hypothesis testing. Organ. Res. Methods 2016, 19, 562–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigelt, O.; Syrek, C.J.; Schmitt, A.; Urbach, T. Finding peace of mind when there still is so much left undone-a diary study on how job stress, competence need satisfaction, and proactive work behavior contribute to work-related rumination during the weekend. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauvola, R.S.; Rudolph, C.W.; Zacher, H. Handling time in occupational stress and well-being research: Considerations, examples and recommendations. Available online: psyarxiv.com/9bwcd. (accessed on 7 June 2021).

| Variable | ICC | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Goal attainment, problem-solving, task-related success | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.45 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.04 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.74 | −0.01 | 0.38 | |

| 2. | Perceived competence in or through social interactions | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.56 | −.02 | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.16 | −0.12 | 0.77 | −0.10 | 0.45 | |

| 3. | Work-related good news | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.36 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.09 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.56 | 0.03 | 0.23 | |

| 4. | Passively experienced positive events | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.54 | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.07 | −0.15 | −0.18 | −0.25 | 0.76 | −0.20 | 0.45 | |

| 5. | Praise, appreciation, positive feedback | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 0.56 | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.10 | −0.09 | 0.82 | −0.02 | 0.43 | |

| 6. | Technical difficulties, problems with work tools and equipment | 0.45 | −0.07 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.15 | −0.04 | 0.46 | −0.13 | |

| 7. | Hindrances in goal attainment, obstacles in completing work tasks, overload | 0.39 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.67 | −0.04 | |

| 8. | Problems in interactions with clients or patients | 0.41 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.04 | |

| 9. | Ambiguity, insecurity, loss of control | 0.45 | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.13 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.44 | 0.18 | 0.45 | 0.37 | -0.04 | 0.71 | −0.15 | |

| 10. | Conflicts and communication problems | 0.43 | −0.07 | −0.16 | 0.00 | −0.16 | −0.06 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.51 | −0.15 | 0.74 | −0.13 | |

| 11. | Managerial and internal problems, organizational climate | 0.49 | 0.05 | −0.10 | 0.03 | −0.23 | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.33 | 0.46 | −0.14 | 0.64 | −0.15 | |

| 12. | Positive events | 0.53 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 0.76 | 0.84 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.13 | −0.10 | −0.09 | 0.54 | |

| 13. | Negative events | 0.57 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.17 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.63 | -0.05 | −0.15 | |

| 14. | Work engagement | 0.61 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 0.36 | −0.12 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.17 | −0.09 | −0.11 | 0.45 | −0.13 | |

| 15. | Work engagement (lagged) | -- | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 0.42 | −0.13 | −0.01 | 0.09 | −0.17 | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.56 | −0.11 | 0.67 |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Gender a, b | 0.77 | 0.42 | -−0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.09 | −0.07 | −0.12 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.02 | |

| 2. | Age in years b | 35.75 | 10.38 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.28 | −0.15 | −0.14 | 0.04 | −0.16 | 0.11 | |

| 3. | Goal attainment, problem-solving, task-related success | 3.17 | 0.87 | 0.15 | −0.04 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.37 | −0.13 | −0.19 | 0.07 | −0.14 | −0.14 | −0.10 | 0.69 | −0.16 | 0.45 | |

| 4. | Perceived competence in or through social interactions | 3.37 | 0.86 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.72 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.64 | −0.05 | −0.22 | 0.09 | −0.19 | −0.23 | −0.22 | 0.82 | −0.21 | 0.48 | |

| 5. | Work-related good news | 1.53 | 0.75 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.49 | −0.05 | −0.17 | 0.07 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.11 | 0.67 | −0.09 | 0.50 | |

| 6. | Passively experienced positive events | 2.59 | 1.11 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.61 | −0.08 | −0.17 | 0.02 | −0.29 | −0.23 | −0.34 | 0.80 | −0.27 | 0.67 | |

| 7. | Praise, appreciation, positive feedback | 2.47 | 1.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.45 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.72 | −0.12 | −0.22 | −0.02 | −0.10 | −0.26 | −0.20 | 0.83 | −0.23 | 0.63 | |

| 8. | Technical difficulties, problems with work tools and equipment | 1.76 | 0.98 | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.16 | −0.32 | 0.01 | −0.18 | −0.19 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.34 | −0.11 | 0.61 | −0.23 | |

| 9. | Hindrances in goal attainment, obstacles in completing work tasks, overload | 1.85 | 1.1 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.21 | −0.29 | −0.10 | −0.24 | −0.14 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.15 | −0.25 | 0.67 | −0.13 | |

| 10. | Problems in interactions with clients or patients | 1.56 | 0.82 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.14 | 0.04 | −0.19 | −0.17 | 0.16 | 0.46 | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.53 | −0.06 | |

| 11. | Ambiguity, insecurity, loss of control | 1.9 | 0.98 | −0.03 | −0.27 | −0.15 | −0.29 | 0.00 | −0.37 | –0.19 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.58 | 0.52 | −0.21 | 0.76 | −0.22 | |

| 12. | Conflicts and communication problems | 1.6 | 0.83 | −0.07 | −0.18 | −0.16 | −0.40 | 0.01 | −0.34 | −0.31 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.39 | 0.67 | 0.67 | −0.25 | 0.83 | −0.26 | |

| 13. | Managerial and internal problems, organizational climate | 1.63 | 0.92 | −0.09 | −0.15 | −0.11 | −0.33 | −0.06 | −0.47 | −0.28 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.65 | 0.65 | −0.26 | 0.71 | −0.27 | |

| 14. | Positive events | 2.63 | 0.68 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.64 | 0.82 | 0.86 | −0.22 | −0.25 | −0.14 | −0.27 | −0.32 | −0.33 | −0.26 | 0.72 | |

| 15. | Negative events | 1.72 | 0.59 | −0.08 | −0.19 | −0.20 | −0.40 | −0.03 | −0.41 | −0.29 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.55 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.74 | −0.35 | −0.29 | |

| 16. | Work engagement | 2.42 | 1.05 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.70 | 0.66 | −0.27 | −0.12 | −0.10 | −0.28 | − 0.27 | −0.33 | 0.75 | −0.32 |

| Parameter | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | SE | t | γ | SE | t | |

| Level 2 (person-level) | ||||||

| Intercept | 2.44 | 0.07 | 33.62 | 2.43 | 0.07 | 33.50 |

| Person-mean positive events | 1.21 | 0.13 | 9.64 *** | 1.21 | 0.12 | 9.70 *** |

| Person-mean negative events | −0.12 | 0.13 | −0.92 | −0.13 | 0.13 | −0.97 |

| Level 1 (week-level) | ||||||

| Time | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.43 |

| Positive events (lagged week n−1) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.49 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.57 |

| Negative events (lagged week n−1) | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.24 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.20 |

| Positive events (week n) | 0.74 | 0.06 | 12.52 *** | 0.72 | 0.06 | 12.12 *** |

| Negative events (week n) | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.86 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.77 |

| Interactions | ||||||

| Positive events x lagged positive events | −0.07 | 0.11 | −0.61 | −0.09 | 0.12 | −0.76 |

| Negative events x lagged negative events | −0.02 | 0.20 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.20 | −0.24 |

| Positive x lagged negative events | 0.40 | 0.15 | 2.69 ** | |||

| Negative events x lagged positive | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.59 | |||

| Variance components | ||||||

| Level 2 intercept variance | 0.32 | 0.33 | ||||

| Positive events slope variance | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| Negative events slope variance | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Lagged negative events slope variance | 0.06 | 0.06 | ||||

| Level 1 intercept variance | 0.26 | 0.25 | ||||

| Deviance (df) | 920.43 | (21) | 913.27 | * (23) | ||

| AIC | 962.43 | 959.27 | ||||

| BIC | 1050.51 | 1055.74 | ||||

| Parameter | Growth Model 1 | Growth Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | SE | t | γ | SE | t | |

| Level 2 (person-level) | ||||||

| Intercept | 2.48 | 0.06 | 38.36 | 2.47 | 0.06 | 38.63 |

| Person-mean positive events | 1.11 | 0.10 | 11.58 *** | 0.98 | 0.12 | 8.36 *** |

| Person-mean negative events | −0.18 | 0.11 | −1.70 | −0.11 | 0.13 | −0.91 |

| Level 1 (week-level) | ||||||

| Time | −0.01 | 0.01 | −2.05 * | −0.01 | 0.01 | −2.20 * |

| Cross-level interactions | ||||||

| Person-mean positive events x time | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.97 * | |||

| Person-mean negative events x time | −0.02 | 0.02 | −1.13 | |||

| Variance components | ||||||

| Level 2 intercept variance | 0.34 | 0.33 | ||||

| Time slope variance | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| Level 1 intercept variance | 0.39 | 0.39 | ||||

| Deviance (df) | 1857.86 | *** (8) | 1850.93 | * (10) | ||

| AIC | 1873.86 | 1870.93 | ||||

| BIC | 1911.82 | 1918.37 | ||||

| Parameter | Model 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| γ | SE | t | |

| Level 1 (week-level) | |||

| Intercept | 2.37 | 0.08 | 28.38 |

| Time | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.46 |

| Goal attainment, problem-solving, task-related success | 0.23 | 0.03 | 6.70 *** |

| Perceived competence in or through social interactions | 0.07 | 0.03 | 1.97 * |

| Work-related good news | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.58 |

| Passively experienced positive events | 0.16 | 0.03 | 5.59 *** |

| Praise, appreciation, positive feedback | 0.20 | 0.03 | 6.45 *** |

| Technical difficulties, problems with work tools and equipment | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| Health complaints | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.30 |

| Private issues | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.51 |

| Hindrances in goal attainment, obstacles in completing work tasks, overload | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.52 |

| Problems in interactions with clients or patients | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.80 |

| Ambiguity, insecurity, loss of control | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.12 * |

| Conflicts and communication problems | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.25 |

| Managerial and internal problems, organizational climate | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| Variance components | |||

| Level 2 intercept variance | 0.77 | ||

| Time slope variance | 0.00 | ||

| Level 1 intercept variance | 0.27 | ||

| Deviance (df) | 1693.77 | (19) | |

| AIC | 1731.77 | ||

| BIC | 1821.91 | ||

| Parameter | Model 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| γ | SE | t | |

| Level 2 (person-level) | |||

| Intercept | 1.78 | 0.12 | 14.75 |

| Person-mean positive events | 0.90 | 0.11 | 8.16 *** |

| Person-mean negative events | −0.09 | 0.10 | −0.91 |

| Level 1 (week-level) | |||

| Time | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.27 |

| Positive events (lagged week n − 1) | −0.19 | 0.07 | −2.85 * |

| Negative events (lagged week n − 1) | −0.05 | 0.08 | −0.60 |

| Positive events (week n) | 0.73 | 0.06 | 12.19 *** |

| Negative events (week n) | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.37 |

| Work Engagement (lagged week n − 1) | 0.27 | 0.04 | 6.29 *** |

| Interactions | |||

| Positive events x lagged positive events | −0.05 | 0.12 | −0.45 |

| Negative events x lagged negative events | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.08 |

| Positive x lagged negative events | 0.37 | 0.15 | 2.43 * |

| Negative events x lagged positive | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.46 |

| Variance components | |||

| Level 2 intercept variance | 0.17 | ||

| Positive events slope variance | 0.01 | ||

| Negative events slope variance | 0.04 | ||

| Lagged negative events slope variance | 0.07 | ||

| Level 1 intercept variance | 0.27 | ||

| Deviance (df) | 889.48 | (24) | |

| AIC | 937.48 | ||

| BIC | 1038.14 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weigelt, O.; Schmitt, A.; Syrek, C.J.; Ohly, S. Exploring the Engaged Worker over Time—A Week-Level Study of How Positive and Negative Work Events Affect Work Engagement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6699. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136699

Weigelt O, Schmitt A, Syrek CJ, Ohly S. Exploring the Engaged Worker over Time—A Week-Level Study of How Positive and Negative Work Events Affect Work Engagement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(13):6699. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136699

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeigelt, Oliver, Antje Schmitt, Christine J. Syrek, and Sandra Ohly. 2021. "Exploring the Engaged Worker over Time—A Week-Level Study of How Positive and Negative Work Events Affect Work Engagement" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 13: 6699. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136699

APA StyleWeigelt, O., Schmitt, A., Syrek, C. J., & Ohly, S. (2021). Exploring the Engaged Worker over Time—A Week-Level Study of How Positive and Negative Work Events Affect Work Engagement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6699. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136699