Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the effects and potential mechanisms of exercise combined with an enriched environment on learning and memory in rats. Forty healthy male Wistar rats (7 weeks old) were randomly assigned into 4 groups (N = 10 in each group): control (C) group, treadmill exercise (TE) group, enriched environment (EE) group and the TE + EE group. The Morris water maze (MWM) test was used to evaluate the learning and memory ability in all rats after eight weeks of exposure in the different conditions. Moreover, we employed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to determine the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and receptor tyrosine kinase B (TrkB) in the rats. The data showed that the escape latency and the number of platform crossings were significantly better in the TE + EE group compared to the TE, EE or C groups (p < 0.05). In addition, there was upregulation of BDNF and TrkB in rats in the TE + EE group compared to those in the TE, EE or C groups (p < 0.05). Taken together, the data robustly demonstrate that the combination of TE + EE enhances learning and memory ability and upregulates the expression of both BDNF and TrkB in rats. Thus, the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway might be modulating the effect of exercise and enriched environment in improving learning and memory ability in rats.

1. Introduction

Learning and memory are fundamental features in the development and survival of humans and animals. Besides being critical for higher-order brain functions, they are intimately associated with behavioral and psychological consequences. Previous studies have associated the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) signaling pathway with learning and memory [1]. BDNF exerts widespread effects throughout the central nervous system, thus mediating critical processes in learning and memory [2]. Furthermore, other reports have demonstrated a correlation between central and peripheral BDNF in rats and other animals as well as its ability to cross the blood–brain barrier [3,4,5]. Therefore, the peripheral BDNF might be a biomarker for learning and memory functions. BDNF binds to its specific receptor tyrosine kinase B (TrkB) to promote learning and memory performance and participates in the growth, differentiation and repair of neurons [6]. For instance, exogenous introduction of BDNF and its receptor TrkB agonist was shown to prevent stress-induced spatial memory deficits [7,8]. Understanding the role of the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway in mediating learning and memory development remains of immense research interest. An increasing body of evidence from in vivo experiments has shown that enriched environment, physical exercise, learning experiences or social interactions induce changes in the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway, resulting in learning and memory shifts.

The effects of physical exercise on memory retention and learning have been demonstrated both in animal models and humans [9,10,11]. Other studies have demonstrated the neuroprotective effect of regular physical exercise in improving learning and memory in healthy individuals [12,13]. Moreover, recent studies have associated exercise with an increased release of BDNF and TrkB, which are delivered to the brain and might play a role in learning and memory [14,15]. On the other hand, whereas regular physical activity benefits learning and memory over the whole life course, the benefits are dependent on aspects of physical exercise plans such as speed, time or slope [16,17,18]. For instance, moderate treadmill exercise was shown to positively modulate the concentrations of BDNF and its TrkB receptor in experimental animals [19,20]. Therefore, the different exercise intensities have different effects on learning and memory as well as BDNF/TrkB signaling activities. Thus, exercise dosage appears to be an important factor in the achievement of enhanced cognitive capabilities.

On the other hand, an enriched environment entails a combination of complex inanimate and social stimulations [21]. An enriched environment consists of physical exercise, novel stimulants and social interactions [22]. Previous findings showed that learning and memory impairment can be attenuated by a relatively short (a few weeks) exposure to environmental conditions; provision of sensory, exercise or cognitive stimulations; as well as sustained social interactions in rodents [23]. In addition, BDNF and TrkB have been shown to be upregulated in the brain in animals maintained in an enriched environment compared to those in impoverished conditions (isolation, no stimulation for physical or learning experiences) [24]. Moreover, an enriched environment could improve learning and memory, and the up-regulation of BDNF/TrkB is considered to be an important pathway in the improved features. One clear difference between treadmill exercise and voluntary exercise in the enriched environment is the ability to quantify the exercise plans for animals undergoing treadmill exercise. On the contrary, the amount of voluntary exercise in the enriched environment cannot be controlled [25].

Previous studies have demonstrated that either the enriched environment or exercise could be promising strategies in enhancing learning and memory as well as upregulation of the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway, thus highlighting their therapeutic potential [26,27,28]. It has been shown that, compared to a single intervention, combined exercise and enriched environment interventions yield better effects in healthy animals [29,30,31,32]. However, data on the effect of forced exercise combined with voluntary exercise in an enriched environment remains scant. Besides, previous research on learning and memory and the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway has focused on the effectiveness of a single intervention. Here, we evaluated the effect of a combination of exercise and enriched environment interventions on learning and memory ability, as well profiling the expression of the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway in healthy Wistar rats. Based on the above research, we put forward the following hypothesis that the combination of treadmill exercise and enriched environment enhances the learning and memory ability by upregulating the concentrations of BDNF/TrkB in rats.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Animals

Male Wistar rats (6 weeks old), purchased from Laboratory Animal Center (Yangzhou University) [certificate: SCXK (SU) 2017-0007], were used in this study. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Ethical Committee of Yangzhou University. Initially, the rats were housed in standard cages 46 × 30 × 16 cm (L × W × H), 5 per cage for 7 days. On day 8, 40 healthy rats were pulled together and then placed in the same environment, to allow random grouping. Then, all rats were randomly selected and assigned by an independent technician as follows: each rat was randomly picked up from the cage and assigned to the control (C) group, the treadmill exercise (TE) group, the enriched environment (EE) group and the treadmill exercise combined with enriched environment (TE + EE) group in sequence, and the assignment was repeated until all groups reached the designated number of animals (N = 10 in each group). In order to reduce the treadmill exercise stress, the rats in TE and TE + EE groups were allowed to adapt to treadmill exercise for one week period prior to the commencement of the experiments. The experimental protocol consisted of 40 min of daily exercise for 6 days and rest for 1 day. The rats were housed in groups in a controlled room (temperature 23 ± 2 °C; 12 h light/12 h dark cycle, light on at 6 PM and off at 6 AM). Except for the C and the TE groups, food and water were delivered from both sides of the cage. Sawdust bedding (SPF) was provided at approximately 2 cm depth. The rats were 8 weeks of age at the onset of the experiments.

2.2. Groups

2.2.1. Control Group

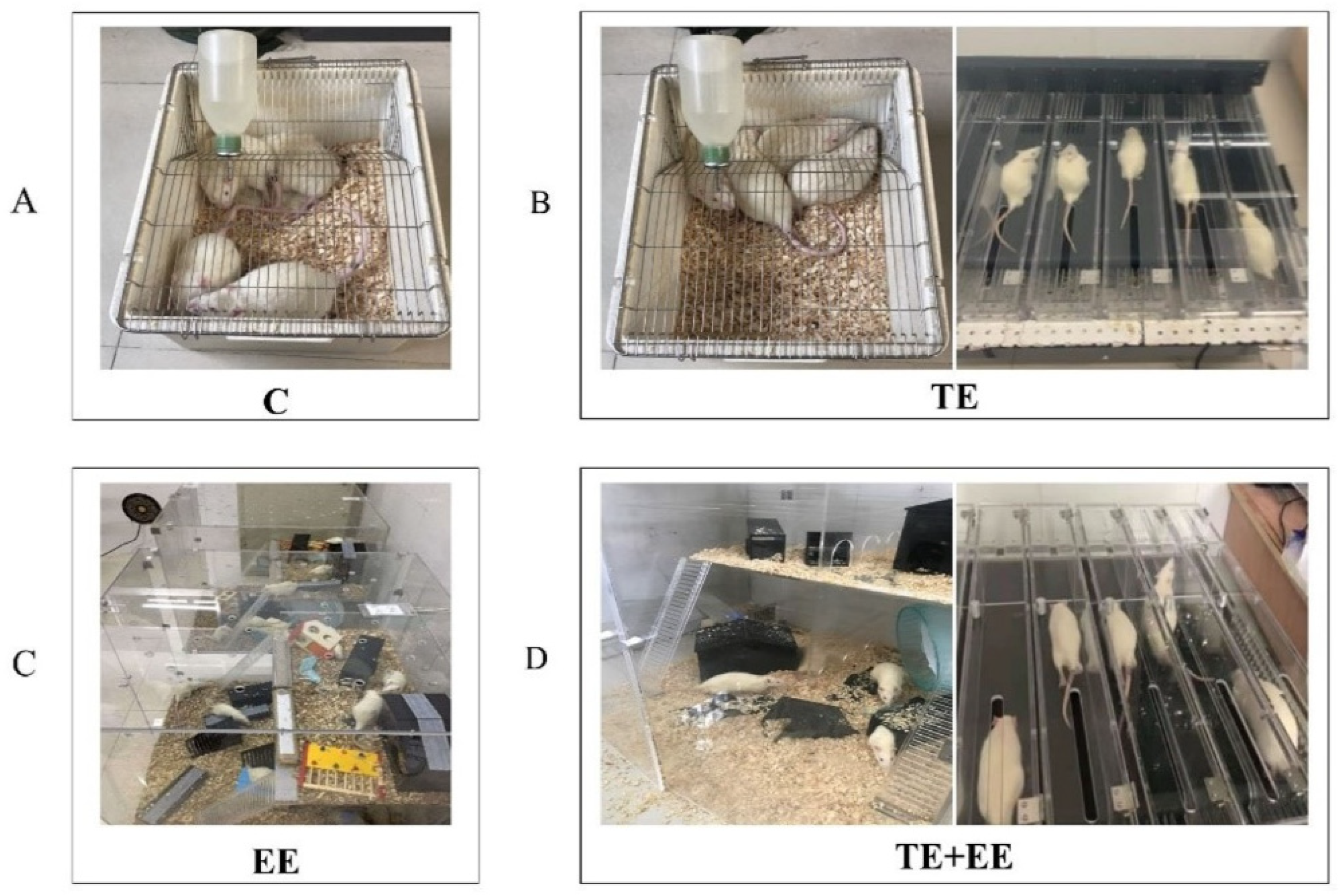

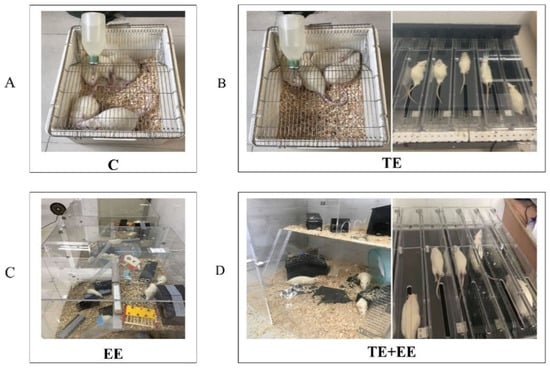

Five animals per cage were housed in standard cages as a control group. The cages had bedding, regular rate chow and plain boiled water (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study groups: (A) Control (C); (B) Treadmill Exercise (TE); (C) Enriched Environment (EE); (D) Treadmill Exercise Combined with Enriched Environment (TE + EE).

2.2.2. Treadmill Exercise

The rats were familiarized with the treadmill to eliminate any exercise-related stress. The rats were adapted to a running treadmill for 40 min daily for 6 days (running at a speed of 5 m/min for the 1st and 2nd days, 10 m/min for the 3rd and 4th days, and 20 m/min for the 5th and 6th days, with 0° inclination.).

As indicated, exercise-induced benefits are dependent on various quantifiable plans of physical exercise such speed, time and slope. We performed regular moderate exercise with newfangled dynamics and exercise load standards as previously described (Bedford et al.).

Eight-week-old rats were then forced to run on a treadmill, with the 0° inclination, at a speed of 20 m/min for 40 min daily, 6 days a week, for 8 consecutive weeks [33].

2.2.3. Enriched Environment

The rats in the EE group were housed for a whole day and then divided into 2 cages (83 × 83 × 83 cm) in order to promote social interaction. Each cage had two floors connected by ramps to promote physical exercise and movement. Various elements of different shapes and textures such as balls, stairs, cubes, tunnels, swings and wheels were placed in the cages and were available to the animals for the 8 weeks of the experiment. The objects in each cage were rotated once a week to stimulate sensory, motor and cognitive functions.

2.2.4. Treadmill Exercise Combined with Enriched Environment

Like in the TE or EE group, one dimension of the intervention contained the treadmill while the other contained toys and food treats. Prior to the intervention, the rats underwent the same adaptive exercise as described in the TE group for 1 week. After 40 min on the treadmill exercise, the rats were kept in the enriched environment for the rest of the day.

2.3. Experimental Design

The rats in each group underwent the experimental protocols for 8 weeks (N = 10 per group). Thereafter, the animals were allowed to acclimatize to the laboratory environment for one day. 6-day Morris water maze (MWM) tests were employed to assess the learning and memory functions in the rats. Testing took place during the light phase of the light/dark cycle and the animals were immediately returned to cages after the tests. To prevent the 6-day MWM test from affecting the intervention effects, all rats were given the intervention for four extra days [34]. On the fifth day, the rats were anaesthetized with urethane and then blood was collected from the abdominal aorta and snap frozen (−80 °C) for further biochemical analysis.

2.4. Morris Water Maze

The Morris water maze (MWM) consisted of a circular galvanized steel pool (diameter = 120 cm; wall height = 50 cm), filled with water at 23 ± 1 °C. A small round escape platform (12 cm diameter) was fixed at the center of one quadrant, 2 cm beneath the water surface. The learning phase consisted of five training days, which randomly started at four different positions. We conducted four trials daily. The rats were placed into the pool facing the maze wall at fixed entry points. In case a rat could not find the platform within 120 s, the experimenter guided the rat to the platform [35]. The rat was then allowed to stay on the platform for 10s to memorize the location [36]. The water maze was surrounded by fixed clues. Moreover, the experimental room was kept invariable during the MWM testing [37]. We recorded the duration the rats spent searching for the platform in each quadrant, with an average of escape latency in the four quadrants as the final escape latency. On the sixth day, the platform was removed, and rats were placed in water to swim with a limitation of 60 s. We then recorded the number of times the rats crossed the exact place containing the submerged platform in each quadrant, with the average number of platform crossings in the four quadrants considered the probe trial of the day. Images of swimming rats were captured by a video camera placed above the center of the pool, which was connected to a computer system running specialized tracking software (ANY-maze, Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL, USA).

2.5. ELISA for Plasma BDNF and TrkB

Using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), we quantified the concentrations of BDNF and TrkB in the plasma of the rats, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). Dispensed antigen standards and samples were added to each well in the 96-well plates, precoated with primary antibodies. After the addition of biotin and enzyme conjugate reagents into the wells, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. We then washed the plates five times in distilled water. Within 15 min of chromogenic reaction, the absorbance was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Nano Drop ND-1000, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using JAMOVI (version 1.6.1) statistical software. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For the MWM test acquisition, the average escape latency time(s) to reach the platform per day was analyzed by repeated measure analysis with days as the within-subjects factor and treatment (C, TE, EE, TE + EE) as the between-subjects factor. The Tukey post-hoc tests were used to evaluate pair-wise differences between the group means. For the probe trial, the number of platform crossings was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with exercise factors (running versus not running) and enrichment (enriched versus not enriched); data were not corrected. In addition, we used the post-hoc tests to evaluate pair-wise differences between the group means. The BDNF and TrkB concentrations were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA using exercise factors (exercise versus not exercise) and enriched environment (enriched versus non enriched environment); data were not corrected. Furthermore, we used post-hoc tests to evaluate pair-wise differences between the group means.

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Performance: The Morris Water Maze (MWM)

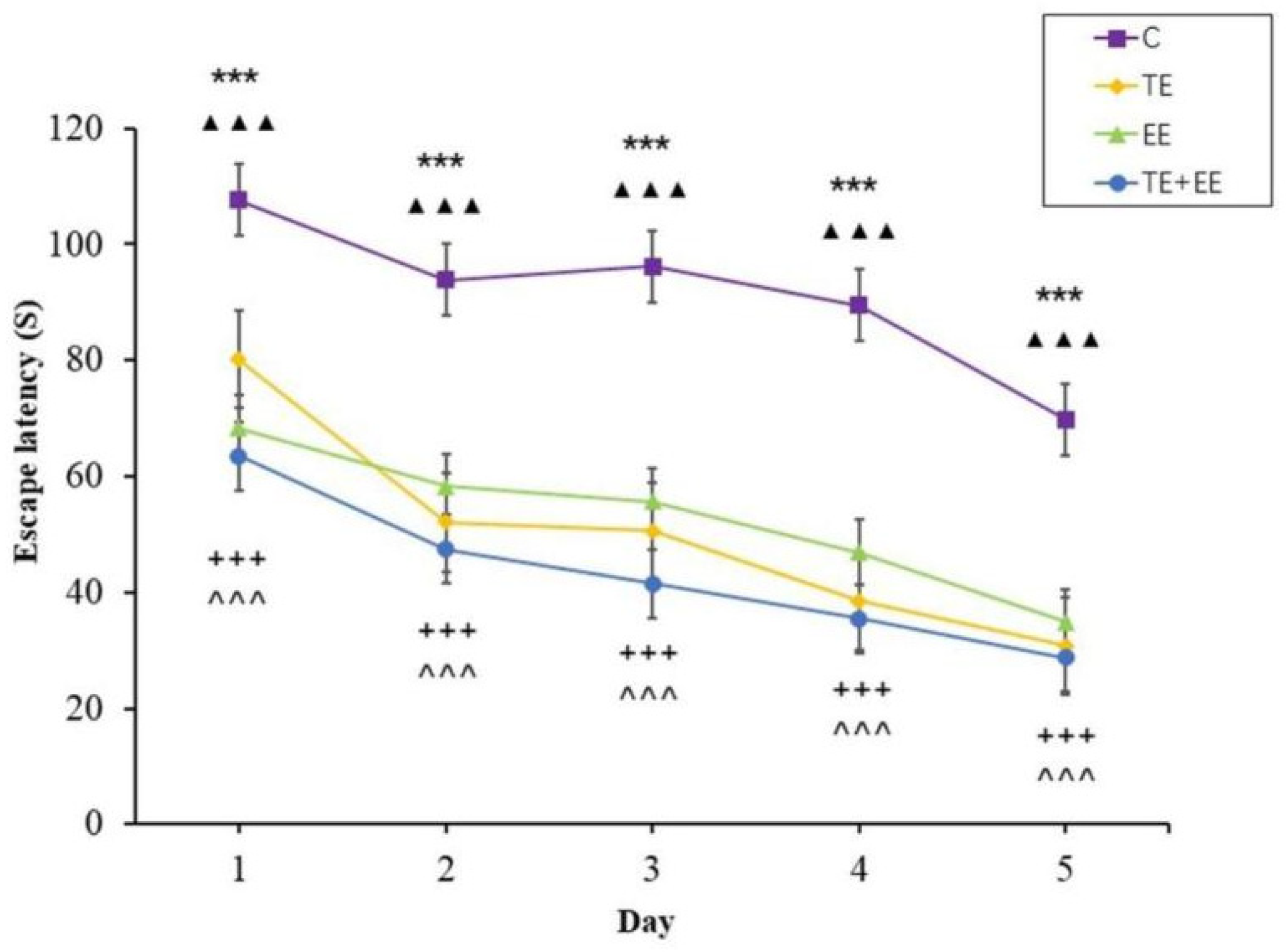

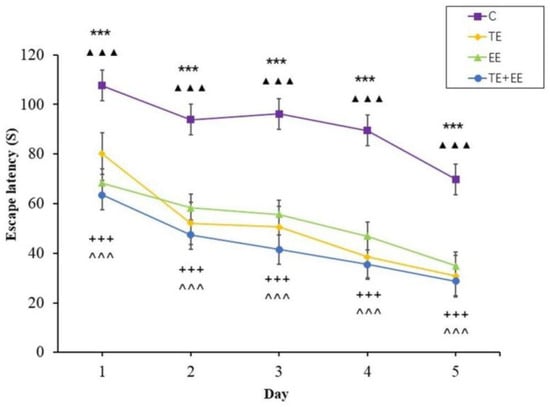

The escape latency data showed that the time effect [F (4,144) = 68.77, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.66] and the group effect [F (3,36) = 103, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.90] were statistically significant, but the time × group interaction effect [F (12,144) = 1.69, p > 0.05, partial η2 = 0.12] was not statistically significant. In addition, the escape latency of each group decreased with the increase in days. Further analysis showed that the TE, EE and TE + EE groups’ escape latency were better compared to that of the C group (p < 0.001) while that of the TE + EE group was better than that of the EE or C groups (p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Average escape latency in the Control (C), Treadmill Exercise (TE), Enriched Environment (EE) and Treadmill Exercise Combined with Enriched Environment (TE + EE) groups (N = 10, ). Note: EE group versus C group, *** p < 0.001; TE group versus C group, ▲▲▲ p < 0.001; TE + EE group versus C group, + + + p < 0.001; TE + EE group versus EE group, ^ ^ ^ p < 0.001.

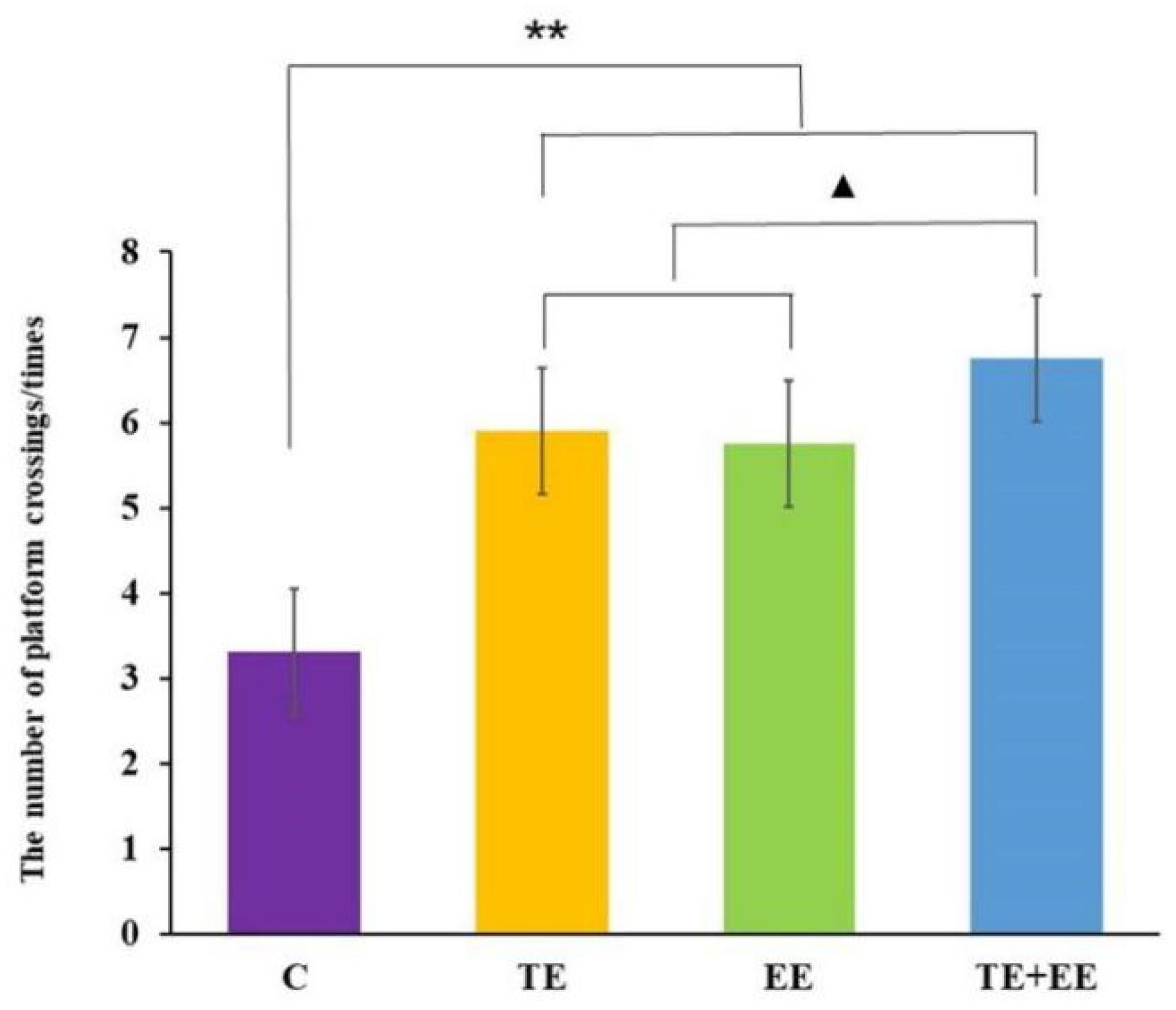

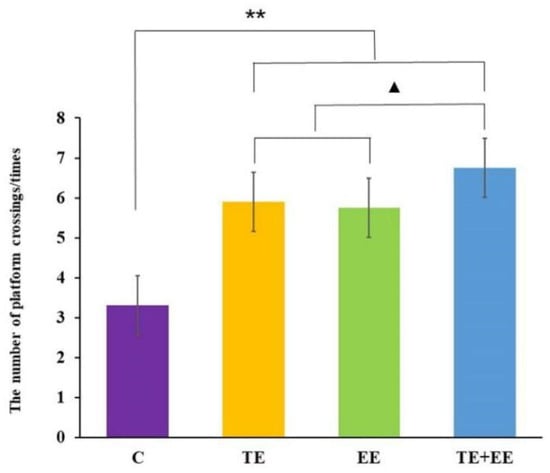

Data from the number of platform crossings showed a statistically significant difference between the exercise effect [F (1,36) = 56.90, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.61], the enriched environment effect [F (1,36) = 47.80, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.57] and the interaction effect of the exercise × enriched environment [F (1,36) = 11.20, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.24] in the probe trail of the rats. Further post-hoc analysis showed that the rats in the TE + EE, TE, or EE groups had a significantly increased number of platform crossings compared with those in the C group (p < 0.001). Unlike between the TE and EE groups, the number of platform crossings of the rats in the TE + EE group was significantly higher than those in the TE or EE groups (p < 0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Average number of platform crossings in the Control (C), Treadmill Exercise (TE), Enriched Environment (EE) and Treadmill Exercise Combined with Enriched Environment (TE + EE) groups (N = 10, ). Note: compared with the C group, ** p < 0.01; compared with TE + EE group, ▲ p < 0.05.

3.2. BDNF and TrkB in Plasma

To define the mechanism of learning and memory in rats exposed to the combination of exercise and an enriched environment, we interrogated the expression profile of the BDNF and TrkB in the rats’ plasma.

Our data demonstrated that there was a significant difference between the exercise effect [F (1,36) = 28.95, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.45] and the enriched environment effect [F (1,36) = 27.02, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.43] as well as the interaction effect [F (1,36) = 5.03, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.12] in the expression of BDNF in the rats. Post-hoc analysis showed that the BDNF concentration was significantly increased in the TE + EE, TE or EE groups compared with those in the C group (p < 0.01). In addition, the BDNF concentration in the TE + EE group was significantly higher than that in the TE or EE groups (p < 0.05). On the contrary, there was no statistically significant difference in the BDNF concentration between the TE and EE groups (p > 0.05).

Similarly, the data showed a significant difference between the exercise effect [F (1,36) = 53.44, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.60] and the enriched environment effect [F (1,36) = 27.88, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.44] as well as the interaction effect [F (1,36) = 4.99, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.12] in the expression of TrkB in the rats. Post-hoc analysis showed that the TrkB concentration was significantly upregulated in the TE + EE, TE or EE groups compared with those in the C group (p < 0.01). Moreover, the TrkB concentration in the TE + EE group was significantly higher than that in the TE or EE groups (p < 0.05). There was, however, no statistically significant difference in the TrkB concentration between the TE and EE groups (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of the plasma concentrations of BDNF and TrkB in the groups ().

4. Discussion

This study investigated the effects and mechanisms of moderate exercise combined with an enriched environment on learning and memory in rats. We further interrogated the role of the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway in mediating learning and memory effects in rats. Our data demonstrate that exercise, enriched environment or exercise combined with an enriched environment intervention improves the learning and memory ability in rats and the effect is mediated by BDNF/TrkB. Interestingly, exercise combined with the enriched environment conferred the best effect.

Our study showed that exercise could improve learning and memory ability and increase the expression of BDNF and TrkB in rats. Our findings are consistent with previous data which used exercise intervention methods alone in rats. Many studies have shown that moderate treadmill exercise has a positive effect on learning and memory. However, the intensity of the exercise determines the optimal learning and memory effects [38,39]. Control of the frequency, duration and intensity of exercise, which are essential aspects in evaluating the beneficial effects of exercise, is more feasible with treadmill exercise, while moderate-intensity running (speed up to 21 m/min) positively affects information acquisition, learning and memory [40,41]. In our study, we used treadmill workouts with defined parameters (such as intensity, duration and cycle). This would explain the fact that the escape latency of the rats in the TE group was lower than that of the C group. In addition, recent data have demonstrated a positive correlation between BDNF expression and different types of physical exercises [42,43,44,45,46]. Similarly, exercise-induced elevation of brain BDNF was reported to be intensity-dependent [47,48]. Moreover, the upregulation of BDNF expression might also be dependent on the duration and frequency of exercise [49,50,51]. This phenomenon has been shown to not only be beneficial to the peripheral nervous system, but also to the central nervous system [52].

We demonstrated that the rats in the EE group exhibited significantly improved learning and memory as well as upregulation in the BDNF/TrkB pathway. Novel stimulants, social interactions and physical exercise are components of the enriched environment. Our study used novel objects, and their rearrangement triggered fresh exploration of the enriched environment by the EE and TE + EE rats. Furthermore, compared with the standard squirrel cage, the enriched environment box had more companions and doorways for communication. Thus, it is possible that the effects of an enriched environment are a function of interaction with the cage mates [53]. In addition, physical exercise has been proposed as a critical component of an enriched environment. However, there is a difference between voluntary exercise in an enriched environment and treadmill exercise. Unlike in a previous study, our findings showed that there was no difference in the learning and memory of rats in the TE and EE groups [54]. This was probably because there was no autonomous runner in the enriched environment. In our study, the two layers of rats in the enriched environment were connected by ramps and contained autonomous runners, which obviously promoted their exercise. In addition, the enriched environment has been shown to increase brain and blood BDNF concentration [55,56,57]. Previous studies reported that BDNF signaling is closely associated with learning and memory functions. The acquisition of learning and memory is accompanied by an increase in the BDNF gene expression in specific brain regions. Blocking the effect of BDNF would lead to declined learning and memory abilities. An appealing feature in the use of BDNF as an indicator for effective enrichment is the correlation between the blood and brain BDNF concentrations, as BDNF can cross the blood–brain barrier [58,59]. Hence, blood-based measures of BDNF have been used as a proxy for brain BDNF [60], allowing for a less invasive assessment of brain changes. BDNF through TrkB receptors contributes to the proliferation, survival and differentiation of neurons in the hippocampus and other brain regions closely related to learning and memory, as well as promoting the induction of long-term potentiation and improving the ability of learning and memory in experimental animals [61]. Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus is an activity-dependent modification of synaptic strength and is considered a potential cellular mechanism underlying learning and memory. Our study demonstrated that the rats housed in total exercise and enriched environment conditions had changes in behavioral and physiological outcomes.

To improve the effectiveness of a single intervention method, the combination of two effective behavioral strategies, such as exercise combined with an enriched environment, presents a feasible alternative. Our analysis showed that exercise combined with an enriched environment intervention has a significant effect in improving the learning and memory ability as well as the expression of the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway in rats. Compared with a single intervention method, exercise combined with a rich environment confers superior effects on improving the learning and memory of rats. In agreement, Wang Chaolei et al. showed that an enriched environment intervention was slightly better than a swimming intervention, while swimming combined with rich environmental intervention was slightly better than enriched environment or swimming interventions [62]. On the other hand, previous studies have assessed the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway. For instance, Du Mingyang et al. showed that memantine and enriched environment therapy could effectively improve the learning and memory abilities in rapidly aging mice. Moreover, it increases the expression of BDNF and TrkB in the hippocampus [63]. Nasroallah Moradi Kor showed that combined enrichment of spirulina or combined exercise of spirulina has a synergistic effect on the hippocampal BDNF levels and dendritic morphology [64].

A number of limitations need to be noted regarding the present study. Firstly, our study only included male rats and could not be duplicated in female rats. It is reported that estrogen might affect the behavior of female rats [65,66]. Secondly, we only included healthy rats. It is possible that these results might not be applicable to other groups with cognitive dysfunctional model rats. Future studies need to assess cognitive ability after intervention in impaired models to provide early treatment strategies. Lastly, although our data robustly demonstrates that 8-week treadmill exercise can improve the learning and memory ability and upregulated expression of BDNF/TrkB in rats, previous literature proposed that a longer intervention period may stabilize the intervention effect on learning and memory [67,68]. Future studies need to investigate the effects of longer intervention cycles on learning and memory, as well as related mechanisms. In short, these limitations mean that the study findings need to be interpreted cautiously.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, our data robustly demonstrates that exercise combined with an enriched environment can improve the learning and memory ability in rats. The improve learning and memory ability might be mediated by the upregulated expression of BDNF/TrkB.

Author Contributions

A.C. designed and performed the study. L.Z. (Lina Zhu) oversaw the data collection. L.X. and L.Z. (Linna Zhu) analyzed the data and wrote the initial manuscript. D.C., K.C. and Z.L. monitored the data quality. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partly funded by grants received by Aiguo Chen from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771243) and the Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation (141113).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yangzhou University following the Ethical Committee approved this study (ethical code: YZU-TYXY-32 and date of approval: 1 April 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Huang, E.J.; Reichardt, L.F. Neurotrophins: Roles in neuronal development and function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 24, 677–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, A.K.; Katz, L.C.; Lo, D.C. Neurotrophins and synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1999, 22, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartorius, A.; Hellweg, R.; Litzke, J.; Vogt, M.; Dormann, C.; Vollmayr, B.; Danker-Hopfe, H.; Gass, P. Correlations and discrepancies between serum and brain tissue levels of neurotrophins after electroconvulsive treatment in rats. Pharmacopsychiatry 2009, 42, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karege, F.; Schwald, M.; Cisse, M. Postnatal developmental profile of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rat brain and platelets. Neurosci. Lett. 2002, 328, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, U.E.; Hellweg, R.; Seifert, F.; Schubert, F.; Gallinat, J. Correlation between serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor level and an in vivo marker of cortical integrity. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 62, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, W.J. From acquisition to consolidation: On the role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling in hippocampal-dependent learning. Learn. Mem. 2002, 9, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.M.; Leem, Y.H. Chronic stress-induced memory deficits are reversed by regular exercise via ampk-mediated BDNF induction. Neuroscience 2016, 324, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-García, A.; Knafo, S.; Pereda-Pérez, I.; Esteban, J.A.; Venero, C.; Armario, A. Administration of the TrkB receptor agonist 7,8-dihydroxyflavone prevents traumatic stress-induced spatial memory deficits and changes in synaptic plasticity. Hippocampus 2016, 26, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabouri, M.; Kordi, M.; Shabkhiz, F.; Taghibeikzadehbadr, P.; Geramian, Z.S. Moderate treadmill exercise improves spatial learning and memory deficits possibly via changing PDE-5, IL-1 beta and pCREB expression. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 139, 111056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, K.I.; Voss, M.W.; Prakash, R.S.; Basak, C.; Szabo, A.; Chaddock, L.; Kim, J.S.; Heo, S.; Alves, H.; White, S.M.; et al. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3017–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dongen, E.V.; Kersten, I.H.P.; Wagner, I.C.; Morris, R.G.M.; Fernández, G. Physical exercise performed four hours after learning improves memory retention and increases hippocampal pattern similarity during retrieval. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 1722–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joubert, C.; Chainay, H. Aging brain: The effect of combined cognitive and physical training on cognition as compared to cognitive and physical training alone—A systematic review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 1267–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, T.R.; Hsiung, A.; Leitner, B.P.; Duckworth, C.J.; Balderston, N.L.; Chen, K.Y.; Grillon, C.; Ernst, M. Exercise modulates the interaction between cognition and anxiety in humans. Cogn. Emot. 2019, 33, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaynman, S.; Ying, Z.; Gómez-Pinilla, F. Exercise induces BDNF and synapsin I to specific hippocampal subfields. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 76, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiar, A.J.; Tuon, T.; Pinho, C.A.; Silva, L.A.; Andreazza, A.C.; Kapczinski, F.; Quevedo, J.; Streck, E.L.; Pinho, R.A. Intense exercise induces mitochondrial dysfunction in mice brain. Neurochem. Res. 2008, 33, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azimi, M.; Gharakhanlou, R.; Naghdi, N.; Khodadadi, D.; Heysieattalab, S. Moderate treadmill exercise ameliorates amyloid-beta-induced learning and memory impairment, possibly via increasing AMPK activity and up-regulation of the PGC-1alpha/FNDC5/BDNF pathway. Peptides 2018, 102, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.F.; Ku, N.W.; Wang, T.F.; Yang, Y.H.; Shih, Y.H.; Wu, S.Y.; Lee, C.W.; Yu, M.; Yang, T.T.; Kuo, Y.M. Long-Term Moderate Exercise Rescues Age-Related Decline in Hippocampal Neuronal Complexity and Memory. Gerontology 2018, 64, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafia, S.; Vafaei, A.A.; Samaei, S.A.; Bandegi, A.R.; Rafiei, A.; Valadan, R.; Hosseini-Khah, Z.; Mohammadkhani, R.; Rashidy-Pour, A. Effects of moderate treadmill exercise and fluoxetine on behavioural and cognitive deficits, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction and alternations in hippocampal BDNF and mRNA expression of apoptosis-related proteins in a rat model of post-traumatic stress disorder. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2017, 139, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just-Borras, L.; Hurtado, E.; Cilleros-Mane, V.; Biondi, O.; Charbonnier, F.; Tomas, M.; Garcia, N.; Tomas, J.; Lanuza, M.A. Running and swimming prevent the deregulation of the BDNF/TrkB neurotrophic signalling at the neuromuscular junction in mice with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 3027–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.F.; Chaves, R.S.; Silva, C.M.; Chaves, J.C.S.; Melo, K.P.; Ferrari, M.F.R. BDNF trafficking and signaling impairment during early neurodegeneration is prevented by moderate physical activity. IBRO Rep. 2016, 1, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, M.R.; Bennett, E.L.; Hebert, M.; Morimoto, H. Social grouping cannot account for cerebral effects of enriched environments. Brain Res. 1978, 153, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, L.S.; Francis, N.; Popescu, D.L.; Anderson, M.E.; Hatfield, J.; Xu, F.; Anderson, B.J.; Van Nostrand, W.E.; Robinson, J.K. Environmental enrichment: Disentangling the influence of novelty, social, and physical activity on cerebral amyloid angiopathy in a transgenic mouse model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Gallegos, A.; Rojas-Carvajal, M.; Salas, S.; Saborio-Arce, A.; Fornaguera-Trias, J.; Brenes, J.C. Age-dependent effects of environmental enrichment on spatial memory and neurochemistry. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2015, 118, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratta, P.; Sanità, P.; Bonanni, R.L.; de Cataldo, S.; Angelucci, A.; Rossi, R.; Origlia, N.; Domenici, L.; Carmassi, C.; Piccinni, A.; et al. Clinical correlates of plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor in post-traumatic stress disorder spectrum after a natural disaster. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 244, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solinas, M.; Thiriet, N.; El, R.R.; Lardeux, V.; Jaber, M. Environmental enrichment during early stages of life reduces the behavioral, neurochemical, and molecular effects of cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, M.W.; Ploughman, M.; Glynn, L.; Corbett, D. Aerobic exercise effects on neuroprotection and brain repair following stroke: A systematic review and perspective. Neurosci. Res. 2014, 87, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondi, C.O.; Klitsch, K.C.; Leary, J.B.; Kline, A.E. Environmental enrichment as a viable neurorehabilitation strategy for experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotraum. 2014, 31, 873–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajhede Gram, M.; Gade, L.; Wogensen, E.; Mogensen, J.; Malá, H. Equal effects of typical environmental and specific social enrichment on posttraumatic cognitive functioning after fimbria-fornix transection in rats. Brain Res. 2015, 1629, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadalipour, A.; Ghodrati-Jaldbakhan, S.; Samaei, S.A.; Rashidy-Pour, A. Deleterious effects of prenatal exposure to morphine on the spatial learning and hippocampal BDNF and long-term potentiation in juvenile rats: Beneficial influences of postnatal treadmill exercise and enriched environment. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2018, 147, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wu, Y.; Jia, J.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, K.; Guo, Z.; Shen, L.; Hu, R. Enrichment-induced exercise to quantify the effect of different housing conditions: A tool to standardize enriched environment protocols. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 249, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabel, K.; Wolf, S.A.; Ehninger, D.; Babu, H.; Leal-Galicia, P.; Kempermann, G. Additive effects of physical exercise and environmental enrichment on adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. Front. Neurosci. 2009, 3, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapgal, V.; Prem, N.; Hegde, P.; Laxmi, T.R.; Kutty, B.M. Long term exposure to combination paradigm of environmental enrichment, physical exercise and diet reverses the spatial memory deficits and restores hippocampal neurogenesis in ventral subicular lesioned rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2016, 130, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedford, T.G.; Tipton, C.M.; Wilson, N.C.; Oppliger, R.A.; Gisolfi, C.V. Maximum oxygen consumption of rats and its changes with various experimental procedures. J. Appl. Physiol. 1979, 47, 1278–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, L.; Zhongming, L.; Haijun, L.; Yan, Z.; Yongliang, W. Effects of different exercise loads on cognitive ability and expression of VEGF/VEGI in hippocampus of aged rats. Chin. J. Neuroanat. 2018, 34, 572–578. [Google Scholar]

- Frye, C.A. Estrus-associated decrements in a water maze task are limited to acquisition. Physiol. Behav. 1995, 57, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, A.; Mogi, M.; Iwanami, J.; Tsukuda, K.; Min, L.J.; Jing, F.; Iwai, M.; Ito, M.; Horiuchi, M. Female exhibited severe cognitive impairment in type 2 diabetes mellitus mice. Life Sci. 2010, 86, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Q.; Zhao, X.L.; Hou, Y.; Li, S.T.; Hong, Y.; Wang, D.L.; Cheng, Y.Y. Protective effects of green tea polyphenols on cognitive impairments induced by psychological stress in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2009, 202, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrelli, A.; Matkovic, L.; Vacotto, M.; Lopez-Costa, J.J.; Basso, N.; Brusco, A. Aerobic exercise upregulates the BDNF-Serotonin systems and improves the cognitive function in rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2018, 155, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrelli, A.; López-Costa, J.J.; Goñi, R.; López, E.M.; Brusco, A.; Basso, N. Effects of moderate and chronic exercise on the nitrergic system and behavioral parameters in rats. Brain Res. 2011, 1389, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.; Wang, G.W. Effects of treadmill exercise intensity on spatial working memory and long-term memory in rats. Life Sci. 2016, 149, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okudan, N.; Belviranlı, M. Long-term voluntary exercise prevents post-weaning social isolation-induced cognitive impairment in rats. Neuroscience 2017, 360, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchtold, N.C.; Castello, N.; Cotman, C.W. Exercise and time-dependent benefits to learning and memory. Neuroscience 2010, 167, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradari, S.; Palle, A.; McGreevy, K.R.; Fontan-Lozano, A.; Trejo, J.L. Can Exercise Make You Smarter, Happier, and Have More Neurons? A Hormetic Perspective. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pinilla, F.; Ying, Z.; Roy, R.R.; Molteni, R.; Edgerton, V.R. Voluntary exercise induces a bdnf-mediated mechanism that promotes neuroplasticity. J. Neurophysiol. 2002, 88, 2187–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Pinilla, F.; Ying, Z.; Opazo, P.; Roy, R.R.; Edgerton, V.R. Differential regulation by exercise of BDNF and NT-3 in rat spinal cord and skeletal muscle. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001, 13, 1078–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, S.L.; Johnston, S.C. Of ghosts and sirens: The subtlest lures of industry. Ann. Neurol. 2007, 61, A11–A12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.J.; Liu, J.Y.; Chang, H.; Chen, P.J. Hippocampal neurogenesis and gene expression depend on exercise intensity in juvenile rats. Brain Res. 2008, 1210, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, P.; Yang, Y.; Wang, R. Effects of exercise intensity on spatial memory performance and hippocampal synaptic plasticity in transient brain ischemic rats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhzadeh, F.; Etemad, A.; Khoshghadam, S.; Asl, N.A.; Zare, P. Hippocampal BDNF content in response to short- and long-term exercise. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 36, 1163–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.S.; Ardais, A.P.; Fioreze, G.T.; Mioranzza, S.; Botton, P.H.S.; Souza, D.O.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Porciúncula, L.O. The impact of the frequency of moderate exercise on memory and brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling in young adult and middle-aged rats. Neuroscience 2012, 222, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalise, S.; Cavalli, L.; Ghuman, H.; Wahlberg, B.; Gerwig, M.; Chisari, C.; Ambrosio, F.; Modo, M. Biological effects of dosing aerobic exercise and neuromuscular electrical stimulation in rats. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, Q.; Xie, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Dong, C.; Fang, L.; Ding, J.; Wang, T. Blocking of BDNF-TrkB signaling inhibits the promotion effect of neurological function recovery after treadmill training in rats with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2019, 57, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapiro, S.J. Effects of social manipulations and environmental enrichment on behavior and cell-mediated immune responses in rhesus macaques. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 2002, 73, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrogini, P.; Lattanzi, D.; Ciuffoli, S.; Betti, M.; Fanelli, M.; Cuppini, R. Physical exercise and environment exploration affect synaptogenesis in adult-generated neurons in the rat dentate gyrus: Possible role of BDNF. Brain Res. 2013, 1534, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, P.; Brassard, P.; Adser, H.; Pedersen, M.V.; Leick, L.; Hart, E.; Secher, N.H.; Pedersen, B.K.; Pilegaard, H. Evidence for a release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor from the brain during exercise. Exp. Physiol. 2009, 94, 1062–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branchi, I.; D Andrea, I.; Fiore, M.; Di Fausto, V.; Aloe, L.; Alleva, E. Early social enrichment shapes social behavior and nerve growth factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in the adult mouse brain. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 60, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Yee, B.K.; Nyffeler, M.; Winblad, B.; Feldon, J.; Mohammed, A.H. Influence of differential housing on emotional behaviour and neurotrophin levels in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2006, 169, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B. BDNF and activity-dependent synaptic modulation. Learn. Mem. 2003, 10, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.B.; Williamson, R.; Santini, M.A.; Clemmensen, C.; Ettrup, A.; Rios, M.; Knudsen, G.M.; Aznar, S. Blood BDNF concentrations reflect brain-tissue BDNF levels across species. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 14, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Banks, W.A.; Fasold, M.B.; Bluth, J.; Kastin, A.J. Transport of brain-derived neurotrophic factor across the blood-brain barrier. Neuropharmacology 1998, 37, 1553–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliss, T.V.; Collingridge, G.L. A synaptic model of memory: Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 1993, 361, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.L. The Effects of Swimming Movement and Rich Environment on Autism Rats’ Learning and Memory Ability and Mechanism Research. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Du, M.; Guan, Q.; Wang, X. Effects of Memantine combined with enriched environment on the expression of brain derived neurophic factor and tyrosine kinase receptor B in hippocampus and the learning and memory ability of senescence accelerated mouse prone 8. J. Clin. Neurol. 2013, 26, 278–281. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi-Kor, N.; Ghanbari, A.; Rashidipour, H.; Yousefi, B.; Bandegi, A.R.; Rashidy-Pour, A. Beneficial effects of Spirulina platensis, voluntary exercise and environmental enrichment against adolescent stress induced deficits in cognitive functions, hippocampal BDNF and morphological remolding in adult female rats. Horm. Behav. 2019, 112, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, S.G.; Juraska, J.M. Spatial and nonspatial learning across the rat estrous cycle. Behav. Neurosci. 1997, 111, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, L.A.; Kavaliers, M.; Ossenkopp, K.P.; Hampson, E. Gonadal hormone levels and spatial learning performance in the Morris water maze in male and female meadow voles, Microtus pennsylvanicus. Horm. Behav. 1995, 29, 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennard, J.; Woodruff-Pak, D.S. Aging and exercise effects on motor learning and spatial memory. Ageing Res. 2011, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Qingwei, Y.; Bo, X.; Qing, T. Treadmill exercise improves hippocampal mitochondrial function and learning and memory ability of APP/PS1 mice. Chin. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 35, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).