Association of Structural Social Capital and Self-Reported Well-Being among Japanese Community-Dwelling Adults: A Longitudinal Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

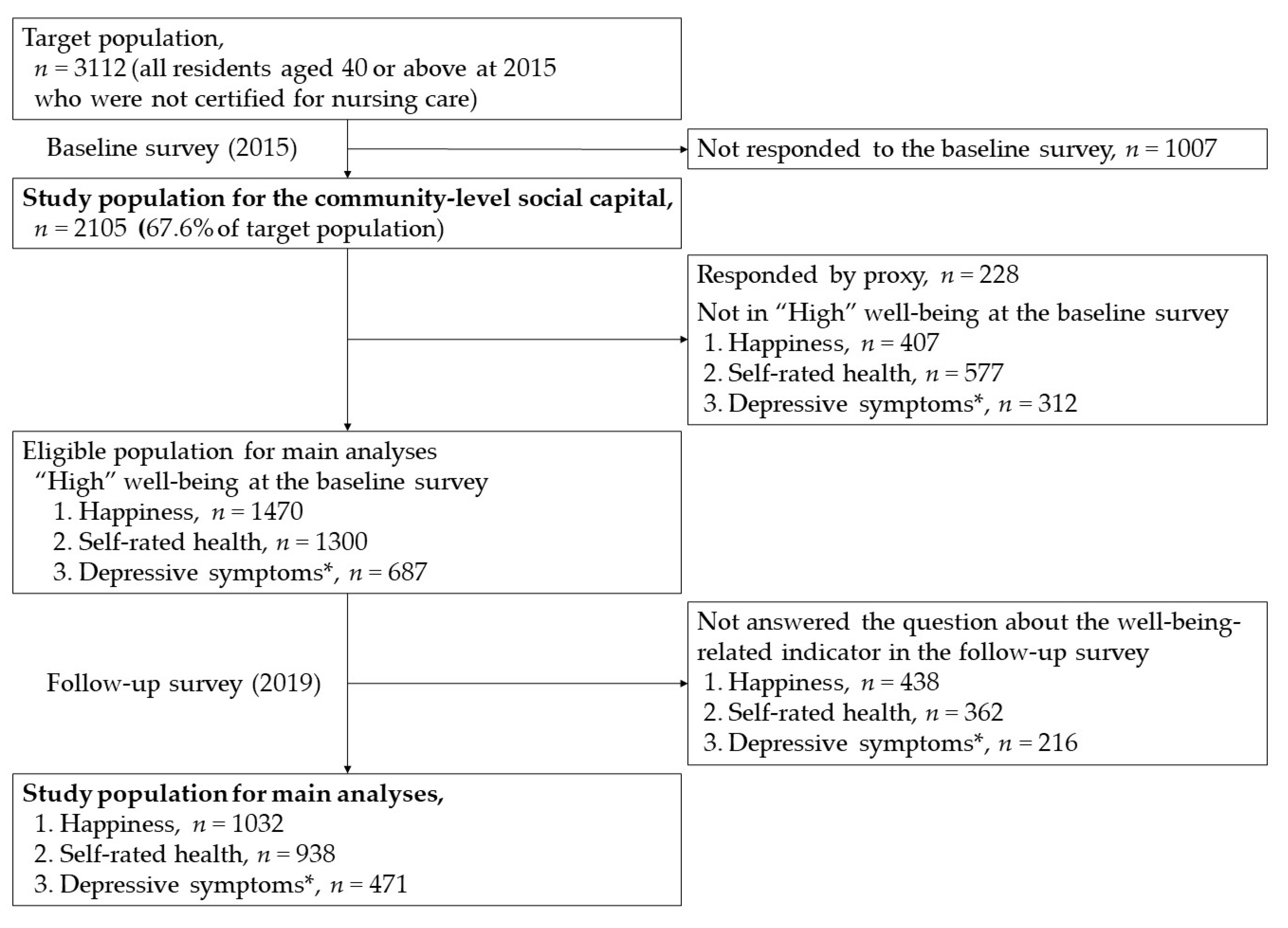

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Outcome Measurement

2.3. Social Capital Measurement

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Area | The Number of the Study Population | Mean Age of the Study Population (years) | The Number of People Who Participate in Local Community Activities (%) | The Number of People Who Have at Least Five Neighbors in Contact (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 95 | 65.2 | 38 | (40.0) | H | 69 | (72.6) | L |

| 2 | 97 | 67.2 | 36 | (37.1) | L | 69 | (71.1) | L |

| 3 | 41 | 63.7 | 15 | (36.6) | L | 26 | (63.4) | L |

| 4 | 69 | 68.6 | 54 | (78.3) | H | 62 | (89.9) | H |

| 5 | 24 | 69.5 | 14 | (58.3) | H | 18 | (75.0) | H |

| 6 | 18 | 71.1 | 7 | (38.9) | L | 12 | (66.7) | L |

| 7 | 19 | 65.3 | 12 | (63.2) | H | 13 | (68.4) | L |

| 8 | 77 | 65.5 | 31 | (40.3) | H | 56 | (72.7) | L |

| 9 | 56 | 71.7 | 22 | (39.3) | L | 35 | (62.5) | L |

| 10 | 65 | 66.6 | 23 | (35.4) | L | 48 | (73.8) | H |

| 11 | 39 | 67.4 | 17 | (43.6) | H | 28 | (71.8) | L |

| 12 | 96 | 67.1 | 38 | (39.6) | H | 74 | (77.1) | H |

| 13 | 126 | 67.6 | 54 | (42.9) | H | 105 | (83.3) | H |

| 14 | 104 | 65.9 | 62 | (59.6) | H | 82 | (78.8) | H |

| 15 | 26 | 69.2 | 11 | (42.3) | H | 22 | (84.6) | H |

| 16 | 84 | 68.1 | 33 | (39.3) | L | 57 | (67.9) | L |

| 17 | 38 | 63.2 | 13 | (34.2) | L | 24 | (63.2) | L |

| 18 | 14 | 66.8 | 2 | (14.3) | L | 10 | (71.4) | L |

| 19 | 72 | 62.0 | 26 | (36.1) | L | 45 | (62.5) | L |

| 20 | 12 | 62.0 | 5 | (41.7) | H | 9 | (75.0) | H |

| 21 | 33 | 70.3 | 22 | (66.7) | H | 29 | (87.9) | H |

| 22 | 89 | 70.0 | 24 | (27.0) | L | 66 | (74.2) | H |

| 23 | 106 | 68.0 | 62 | (58.5) | H | 92 | (86.8) | H |

| 24 | 50 | 70.0 | 19 | (38.0) | L | 40 | (80.0) | H |

| 25 | 33 | 65.2 | 21 | (63.6) | H | 26 | (78.8) | H |

| 26 | 27 | 66.0 | 16 | (59.3) | H | 19 | (70.4) | L |

| 27 | 40 | 67.7 | 28 | (70.0) | H | 35 | (87.5) | H |

| 28 | 77 | 66.6 | 22 | (28.6) | L | 58 | (75.3) | H |

| 29 | 95 | 65.9 | 35 | (36.8) | L | 77 | (81.1) | H |

| 30 | 68 | 68.2 | 23 | (33.8) | L | 54 | (79.4) | H |

| 31 | 76 | 64.5 | 26 | (34.2) | L | 52 | (68.4) | L |

| 32 | 112 | 66.3 | 55 | (49.1) | H | 80 | (71.4) | L |

| 33 | 17 | 68.3 | 6 | (35.3) | L | 10 | (58.8) | L |

| 34 | 106 | 63.2 | 29 | (27.4) | L | 63 | (59.4) | L |

| N/A * | 4 | 69.5 | ||||||

| Total | 2105 | 67.0 | 901 | (42.9) | 1565 | (74.5) | ||

References

- Grad, F.P. The Preamble of the Constitution of the World Health Organization. Bull. World Health Organ. 2002, 80, 981–984. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, J.; Andrade, J.; Eisner, M.; Ironmonger, M.; Maxwell, J.; Muir, E.; Siriwardena, R.; Thwaites, S. To Treat? To Befriend? To Prevent? Patients’ and GPs’ Views of the Doctor’s Role. Scand. J. Prim Health Care 1997, 15, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Steptoe, A.; Deaton, A.; Stone, A.A. Subjective Wellbeing, Health, and Ageing. Lancet 2015, 385, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Pressman, S.D.; Hunter, J.; Delgadillo-Chase, D. If, Why, and When Subjective Well-Being Influences Health, and Future Needed Research. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2017, 9, 133–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Tay, L. Advances in Subjective Well-being Research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Kawachi, I. Twenty Years of Social Capital and Health Research: A Glossary. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2017, 71, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Ng, N. Changes in Access to Structural Social Capital and its Influence on Self-Rated Health over Time for Middle-Aged Men and Women: A Longitudinal Study from Northern Sweden. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 130, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Social Capital, Social Cohesion, and Health. In Social Epidemiology, 2nd ed.; Berkman, L.F., Kawachi, I., Glymour, M.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 290–319. [Google Scholar]

- Szreter, S.; Woolcock, M. Health by Association? Social Capital, Social Theory, and the Political Economy of Public Health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 33, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Thinking about Social Change in America. In Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ehsan, A.; Klaas, H.S.; Bastianen, A.; Spini, D. Social Capital and Health: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. SSM Popul. Health 2019, 8, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Putnam, R.D. The Social Context of Well-Being. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1435–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, T.; Martelin, T.; Koskinen, S.; Aro, H.; Alanen, E.; Hyyppä, M. Social Capital as a Determinant of Self-Rated Health and Psychological Well-Being. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostila, M. The Facets of Social Capital. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2011, 41, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.U.; LaGory, M. Social Capital and Mental Distress in an Impoverished Community. City Community 2002, 1, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Subramanian, S.V.; Kawachi, I. Bonding Versus Bridging Social Capital and their Associations with Self Rated Health: A Multilevel Analysis of 40 US Communities. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalonga-Olives, E.; Kawachi, I. The Dark Side of Social Capital: A Systematic Review of the Negative Health Effects of Social Capital. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 194, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, H.; Fujiwara, Y.; Kawachi, I. Social Capital and Health: A Review of Prospective Multilevel Studies. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japanese General Social Surveys (JGSS) Series. Available online: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/ICPSR/series/209 (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Subramanian, S.V.; Kim, D.; Kawachi, I. Covariation in the Socioeconomic Determinants of Self Rated Health and Happiness: A Multivariate Multilevel Analysis of Individuals and Communities in the USA. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, R.A. On the trail of the gold standard for subjective well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 1995, 35, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idler, E.L.; Benyamini, Y. Self-Rated Health and Mortality: A Review of Twenty-Seven Community Studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichida, Y.; Hirai, H.; Kondo, K.; Kawachi, I.; Takeda, T.; Endo, H. Does Social Participation Improve Self-Rated Health in the Older Population? A Quasi-Experimental Intervention Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 94, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewo Sampaio, P.Y.; Sampaio, R.A.C.; Yamada, M.; Arai, H. Systematic Review of the Kihon Checklist: Is it a Reliable Assessment of Frailty? Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 16, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office of the Government of Japan. Social Capital: Looking for a Good Circle of Rich Human Relationships and Civic Activities; Government Printing Office: Tokyo, Japan, 2003. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Imamura, H.; Hamano, T.; Michikawa, T.; Takeda-Imai, F.; Nakamura, T.; Takebayashi, T.; Nishiwaki, Y. Relationships of Community and Individual Level Social Capital with Activities of Daily Living and Death by Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuruta, K.; Shiomitsu, T.; Hombu, A.; Fujii, Y. Relationship between Social Capital and Happiness in a Japanese Community: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 21, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, G. A Modified Poisson Regression Approach to Prospective Studies with Binary Data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 159, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowling, A.; Barber, J.; Morris, R.; Ebrahim, S. Do Perceptions of Neighbourhood Environment Influence Health? Baseline Findings from a British Survey of Aging. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fancourt, D.; Steptoe, A. Community Group Membership and Multidimensional Subjective Well-being in Older Age. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelgrove, J.W.; Pikhart, H.; Stafford, M. A Multilevel Analysis of Social Capital and Self-Rated Health: Evidence from the British Household Panel Survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 1993–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, Y.; Wada, Y.; Ichida, Y.; Nishikawa, M. Which Part of Community Social Capital is Related to Life Satisfaction and Self-Rated Health? A Multilevel Analysis Based on a Nationwide Mail Survey in Japan. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 142, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Inoue, Y.; Shinozaki, T.; Saito, M.; Takagi, D.; Kondo, K.; Kondo, N. Community Social Capital and Depressive Symptoms among Older People in Japan: A Multilevel Longitudinal Study. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Subramanian, S.V.; Kim, D. Social Capital and Health: A Decade of Progress and Beyond. In Social Capital and Health; Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S.V., Kim, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Koyama, S.; Aida, J.; Saito, M.; Kondo, N.; Sato, Y.; Matsuyama, Y.; Tani, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Kondo, K.; Ojima, T.; et al. Community Social Capital and Tooth Loss in Japanese Older People: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujihara, S.; Tsuji, T.; Miyaguni, Y.; Aida, J.; Saito, M.; Koyama, S.; Kondo, K. Does Community-Level Social Capital Predict Decline in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living? A JAGES Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, T.; Kondo, K.; Saito, M.; Nakagawa-Senda, H.; Suzuki, S. Community Social Capital and the Onset of Functional Disability among Older Adults in Japan: A Multilevel Longitudinal Study using Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES) Data. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, T.; Kanamori, S.; Miyaguni, Y.; Hanazato, M.; Kondo, K. Community-Level Sports Group Participation and the Risk of Cognitive Impairment. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 2217–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagomi, A.; Shiba, K.; Kondo, K.; Kawachi, I. Can Social Capital Moderate the Impact of Widowhood on Depressive Symptoms? A Fixed-Effects Longitudinal Analysis. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, R.A. Proxy Responding for Subjective Well-being: A Review. Int. Rev. Res. Ment. Retard. 2002, 25, 183–207. [Google Scholar]

- The Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Glymour, M.M.; Avendano, M.; Kawachi, I. Socioeconomic Status and Health. In Social Epidemiology, 2nd ed.; Berkman, L.F., Kawachi, I., Glymour, M.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 17–62. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Well-Being-Related Indicator | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness | Self-Rated Health | Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| n = 1032 | n = 938 | n = 471 | ||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||||

| Social capital at the community level | ||||||||

| Participation in local community activities | High | 544 | (52.7) | 486 | (51.8) | 237 | (50.3) | |

| Low | 488 | (47.3) | 452 | (48.2) | 234 | (49.7) | ||

| The number of neighbors in contact | High | 554 | (53.7) | 503 | (53.6) | 275 | (58.4) | |

| Low | 478 | (46.3) | 435 | (46.4) | 196 | (41.6) | ||

| Social capital at the individual level | ||||||||

| Participation in local community activities | Participate | 543 | (54.3) | 506 | (55.5) | 260 | (57.4) | |

| Do not participate | 457 | (45.7) | 405 | (44.5) | 193 | (42.6) | ||

| The number of neighbors in contact | Large (≥5) | 881 | (86.6) | 790 | (85.5) | 415 | (89.1) | |

| Small (<5) | 136 | (13.4) | 134 | (14.5) | 51 | (10.9) | ||

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age (years) | 40–49 | 116 | (11.4) | 107 | (11.5) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| 50–59 | 184 | (18.0) | 159 | (17.1) | 0 | (0.0) | ||

| 60–69 | 322 | (31.5) | 299 | (32.2) | 153 | (32.5) | ||

| 70–79 | 289 | (28.3) | 270 | (29.1) | 245 | (52.0) | ||

| ≥80 | 110 | (10.8) | 93 | (10.0) | 73 | (15.5) | ||

| Sex | Female | 585 | (56.9) | 518 | (55.5) | 260 | (55.2) | |

| Male | 444 | (43.1) | 416 | (44.5) | 211 | (44.8) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 861 | (84.6) | 761 | (82.1) | 383 | (81.8) | |

| Not married | 157 | (15.4) | 166 | (17.9) | 85 | (18.2) | ||

| Cohabitants | Yes | 951 | (92.8) | 854 | (91.8) | 423 | (89.8) | |

| No | 74 | (7.2) | 76 | (8.2) | 48 | (10.2) | ||

| Educational attainment (years) | ≥10 | 790 | (77.1) | 719 | (77.2) | 313 | (66.7) | |

| <10 | 234 | (22.9) | 212 | (22.8) | 156 | (33.3) | ||

| History of major diseases * | No | 861 | (83.4) | 795 | (84.8) | 378 | (80.3) | |

| Yes | 171 | (16.6) | 143 | (15.2) | 93 | (19.7) | ||

| Current drinking | No | 496 | (48.9) | 451 | (48.9) | 267 | (57.8) | |

| Yes | 519 | (51.1) | 472 | (51.1) | 195 | (42.2) | ||

| Current smoking | No | 886 | (89.0) | 805 | (89.0) | 423 | (92.6) | |

| Yes | 109 | (11.0) | 100 | (11.0) | 34 | (7.4) | ||

| Outcome/Study Population (%) | Model 1 * | Model 2 † | Model 3 ‡ | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted RR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | p-Value | ||||||||

| Social capital associated with a decline in happiness | |||||||||||||

| Total analyzed population | 109/1032 | (10.6%) | n = 1019 | n = 976 | n = 929 | ||||||||

| at the community level | |||||||||||||

| Participation in local community activities | High | 49/544 | (9.0%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Low | 60/488 | (12.3%) | 1.23 | (0.95–1.59) | 0.117 | 1.18 | (0.90–1.55) | 0.220 | 1.21 | (0.90–1.63) | 0.209 | ||

| The number of neighbors in contact | High | 43/554 | (7.8%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Low | 66/478 | (13.8%) | 1.76 | (1.32–2.34) | <0.001 | 1.58 | (1.15–2.17) | 0.005 | 1.64 | (1.20–2.22) | 0.002 | ||

| at the individual level | |||||||||||||

| Participation in local community activities | Participate | 50/543 | (9.2%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Do not participate | 52/457 | (11.4%) | 1.02 | (0.72–1.46) | 0.901 | 0.95 | (0.67–1.36) | 0.799 | |||||

| The number of neighbors in contact | Large (≥ 5) | 82/881 | (9.3%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Small (< 5) | 23/136 | (16.9%) | 1.61 | (1.10–2.37) | 0.015 | 1.51 | (1.05–2.17) | 0.027 | |||||

| Social capital associated with a decline in self-rating health | |||||||||||||

| Total analyzed population | 189/938 | (20.1%) | n = 925 | n = 888 | n = 847 | ||||||||

| at the community level | |||||||||||||

| Participation in local community activities | High | 92/486 | (18.9%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Low | 97/452 | (21.5%) | 1.16 | (0.87–1.54) | 0.320 | 1.15 | (0.86–1.54) | 0.332 | 1.17 | (0.86–1.58) | 0.320 | ||

| The number of neighbors in contact | High | 98/503 | (19.5%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Low | 91/435 | (20.9%) | 1.08 | (0.81–1.44) | 0.593 | 1.02 | (0.74–1.40) | 0.896 | 1.00 | (0.72–1.39) | 0.982 | ||

| at the individual level | |||||||||||||

| Participation in local community activities | Participate | 106/506 | (20.9%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Do not participate | 75/405 | (18.5%) | 0.84 | (0.62–1.13) | 0.254 | 0.82 | (0.61–1.12) | 0.210 | |||||

| The number of neighbors in contact | Large (≥ 5) | 152/790 | (19.2%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Small (< 5) | 33/134 | (24.6%) | 1.30 | (0.87–1.94) | 0.197 | 1.28 | (0.84–1.96) | 0.249 | |||||

| Social capital associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms | |||||||||||||

| Total analyzed population | 79/471 | (16.8%) | n = 471 | n = 448 | n = 432 | ||||||||

| at the community level | |||||||||||||

| Participation in local community activities | High | 42/237 | (17.7%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Low | 37/234 | (15.8%) | 0.91 | (0.59–1.40) | 0.661 | 0.82 | (0.55–1.23) | 0.345 | 0.79 | (0.51–1.22) | 0.292 | ||

| The number of neighbors in contact | High | 47/275 | (17.1%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Low | 32/196 | (16.3%) | 0.97 | (0.65–1.44) | 0.875 | 0.86 | (0.58–1.27) | 0.440 | 0.77 | (0.51–1.15) | 0.199 | ||

| at the individual level | |||||||||||||

| Participation in local community activities | Participate | 36/260 | (13.8%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Do not participate | 38/193 | (19.7%) | 1.51 | (0.96–2.39) | 0.077 | 1.46 | (0.88–2.41) | 0.144 | |||||

| The number of neighbors in contact | Large (≥5) | 68/415 | (16.4%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Small (<5) | 10/51 | (19.6%) | 1.22 | (0.63–2.35) | 0.549 | 1.13 | (0.58–2.18) | 0.718 | |||||

| The Number of Neighbors in Contact at the Individual Level | Well-Being Related Indicator | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness | Self-Rated Health | Depressive Symptoms | ||||||||||

| n | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | p-Value | n | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | p-Value | n | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | p-Value | ||||

| Have contact with a lot of neighbors (≥20) | 268 | 1.00 | 238 | 1.00 | 142 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Have contact with quite a lot of neighbors (10–19) | 239 | 1.73 | (0.84–3.55) | 0.136 | 212 | 1.02 | (0.71–1.46) | 0.932 | 95 | 1.13 | (0.58–2.20) | 0.713 |

| Have contact with some neighbors (5–9) | 301 | 1.80 | (0.81–4.04) | 0.151 | 279 | 1.00 | (0.69–1.44) | 0.993 | 150 | 1.37 | (0.80–2.35) | 0.246 |

| Have contact with just a few neighbors (<5) | 118 | 2.33 | (1.11–4.85) | 0.025 | 116 | 1.27 | (0.73–2.20) | 0.402 | 44 | 1.37 | (0.74–2.55) | 0.313 |

| Don’t know my neighbors | 3 | 5.10 | (1.02–25.6) | 0.048 | 2 | 3.69 | (1.06–12.8) | 0.040 | 1 | not applicable * | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nogi, K.; Imamura, H.; Asakura, K.; Nishiwaki, Y. Association of Structural Social Capital and Self-Reported Well-Being among Japanese Community-Dwelling Adults: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168284

Nogi K, Imamura H, Asakura K, Nishiwaki Y. Association of Structural Social Capital and Self-Reported Well-Being among Japanese Community-Dwelling Adults: A Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168284

Chicago/Turabian StyleNogi, Kazuya, Haruhiko Imamura, Keiko Asakura, and Yuji Nishiwaki. 2021. "Association of Structural Social Capital and Self-Reported Well-Being among Japanese Community-Dwelling Adults: A Longitudinal Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 16: 8284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168284

APA StyleNogi, K., Imamura, H., Asakura, K., & Nishiwaki, Y. (2021). Association of Structural Social Capital and Self-Reported Well-Being among Japanese Community-Dwelling Adults: A Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168284