Abstract

Mentoring to develop research skills is an important strategy for facilitating faculty success. The purpose of this study was to conduct an integrative literature review to examine the barriers and facilitators to mentoring in health-related research, particularly for three categories: new investigators (NI), early-stage investigators (ESI) and underrepresented minority faculty (UMF). PsychINFO, CINAHL and PubMed were searched for papers published in English from 2010 to 2020, and 46 papers were reviewed. Most papers recommended having multiple mentors and many recommended assessing baseline research skills. Barriers and facilitators were both individual and institutional. Individual barriers mentioned most frequently were a lack of time and finding work–life balance. UMF mentioned barriers related to bias, discrimination and isolation. Institutional barriers included lack of mentors, lack of access to resources, and heavy teaching and service loads. UMF experienced institutional barriers such as devaluation of experience or expertise. Individual facilitators were subdivided and included writing and synthesis as technical skills, networking and collaborating as interpersonal skills, and accountability, leadership, time management, and resilience/grit as personal skills. Institutional facilitators included access to mentoring, professional development opportunities, and workload assigned to research. Advocacy for diversity and cultural humility were included as unique interpersonal and institutional facilitators for UMF. Several overlapping and unique barriers and facilitators to mentoring for research success for NI, ESI and UMF in the health-related disciplines are presented.

1. Introduction

Being a faculty member in higher education is a rewarding career path that typically involves sharing one’s passion about one’s discipline with hundreds of students, collaborating with faculty colleagues, making noteworthy research discoveries, and traveling around the world to intellectually stimulating places to promote one’s ideas. However, compared to 20 years ago, life as a faculty member has become more challenging. The environment is dynamic, and it includes the corporatization of higher education [1], changing student demographics which may lead to a decline in students pursuing higher education [2], increasing college costs and declining government support [3], COVID-19-related changes affecting teaching and research practices [4], and escalating workload demands brought about by increasing teaching and clinical loads, coupled with intensifying expectations for research performance [5]. Research success is undoubtedly one of the most important components to success in the academy, particularly for those pursuing tenure-track careers.

Being a faculty member in higher education is a rewarding career path that typically involves sharing one’s passion about one’s discipline with hundreds of students, collaborating with faculty colleagues, making noteworthy research discoveries, and traveling around the world to intellectually stimulating places to promote one’s ideas. However, compared to 20 years ago, life as a faculty member has become more challenging. The environment is dynamic, and it includes the corporatization of higher education [1], changing student demographics which may lead to a decline in students pursuing higher education [2], increasing college costs and declining government support [3], COVID-19-related changes affecting teaching and research practices [4], and escalating workload demands brought about by increasing teaching and clinical loads, coupled with intensifying expectations for research performance [5]. Research success is undoubtedly one of the most important components to success in the academy, particularly for those pursuing tenure-track careers.

Faculty in the U.S. are categorized by academic rank, which typically corresponds to their level of experience, and whether or not they are in pursuit of tenure. According to the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), tenure is “an indefinite appointment that can be terminated only for cause or under extraordinary circumstances such as financial exigency and program discontinuation;” tenure was originally conceived to safeguard academic freedom, and to protect faculty who study controversial topics [6].

Tenured and tenure-track faculty in the U.S. are evaluated by several university committees using established criteria, over a longitudinal evaluation period (6–7 years). Evaluation criteria for tenured and tenure-track faculty are mainly related to research accomplishments (e.g., publications, grants, and keynote presentations), but also include teaching and service contributions. Individuals who are tenured are typically Associate or Full Professors (with at least 6 years of experience as professors), and tenure-track faculty (with less than 6 years of experience) are assigned the Assistant Professor rank. Non-tenure-track faculty include lecturers, clinical, or teaching-oriented faculty whose longevity and promotion in the academy depends on their ability to deliver high-quality instruction to students.

One of the most critical times of an academic career is when faculty first accept an academic position. New faculty find that their most dramatic adjustments occur within their first year, and they often struggle to learn teaching, research, and service expectations, department culture and norms, and the political nature of the academy [5]. A key element in obtaining tenure is the expectation to secure external funding, a goal that is also increasingly difficult to attain. A study that examined changes in NIH funding over time (2009–2016) for R01 and research project grants concluded that funding increased 2–5% per year, but that the beneficiaries of this growth were experienced investigators—not new investigators (NI) or early-stage investigators (ESI) [7].

A high percentage of new investigators (NI) and early-stage investigators (ESI) are racial and ethnic minorities or underrepresented minority faculty (UMF) [7,8], which includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic/LatinX, Black/African American, or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander individuals. UMF are not represented in university settings at the same proportion as they are in the general population—especially in academic medical schools [9]. Although the percentage of UMF has increased some over the last several years, the percentage of UMF obtaining tenure and promotion to Full Professor has not increased proportionate to their employment [10].

In addition to ethnically diverse faculty, other persons who are underrepresented in higher education include individuals with disabilities, who were homeless, first-generation college graduates, and/or who grew up in foster care, received free or reduced lunches or Special Supplemental Nutrition for Women, Infants or Children (WIC) or obtained Pell grant assistance [11]. While research exists that examines the impact of mentoring students who are disabled [12] or from low SES backgrounds [13], there is a dearth of literature that examines mentoring faculty from these backgrounds to enhance research. Given the lack of research on mentoring faculty from these important but understudied categories of underrepresented faculty, this paper will focus on NI, ESI and ethnic minority faculty.

The other complicating factor in the health-related disciplines is that faculty are increasingly difficult to hire [14]. A recent article summarizing nursing graduate opportunities, which are not unlike other health-related disciplines, noted that nursing faculty are becoming harder to find and recruit as these individuals can make higher than average salaries in the private sector [15]. If they do enter higher education, they may leave the field earlier than desired due to campus climate challenges (e.g., lack of opportunity, lack of value or recognition, or ambiguity regarding institutional expectations for academic success) and/or competing personal responsibilities (e.g., family caregiving and work–life balance) [16]. The dynamic and ever-changing milieu within higher education, combined with heavy workloads, can lead to burnout, which is highest among women and underrepresented minorities [17].

One of the most important strategies for helping NI, ESI and UMF succeed is mentoring. Mentoring in the academy is broadly defined as an experienced professor or professors (mentor(s)) supporting a new professor (mentee) in career-related opportunities, challenges and psychosocial areas [18,19]. Contemporary mentoring takes on many different formats including dyadic, peer, or group, and it can occur face to face or via teleconferencing [12]. The numerous career benefits of mentoring have been summarized in literature reviews [20,21] and meta-analyses [22,23,24], and benefits have been examined across disciplines and academic roles such as leadership [25,26], teaching [27] and research [20,21]. Scholars have concluded that effective mentoring provides direction and empowers self-direction [28]. Numerous benefits to mentoring have been cited in the literature including better attitudes, more satisfaction with the work environment, a greater tendency to hold a senior position, and more career success [22]. The impact of mentoring for academic faculty is so strong, that the American Psychological Association [18] wrote that faculty who are mentored typically have more prolific records of publications and grants—and thus earn stronger performance evaluations, higher salaries, and their careers progress faster.

In addition to literature reviews that examined the overall benefits of mentoring, other literature reviews in the health disciplines have examined the benefits of mentoring for improved clinical practice [29,30,31,32], and for expanding the research capacity of clinical faculty in the health sciences [33]. Buddeberg-Fisher and colleagues [34] and Byrne and Keefe [35] conducted older narrative literature reviews on expanding research capacity of students and faculty in academic medicine and nursing, respectively. Nowell and colleagues [21] conducted a mixed-methods systematic literature review on outcomes of mentoring in nursing and concluded that mentoring had a helpful impact on behavioral, career, attitudinal, relational and motivation outcomes. One emerging review area is related to expanding global research capacity of students and faculty to improve research and ultimately enhance medical care in developing countries [36].

McRae and Zimmerman [20] conducted a systematic literature review of 34 mentoring programs, with a goal to identify outcomes and components of mentoring programs within the health sciences. Their review focused on programs in medicine, nursing and pharmacy, and it included recommendations for growing research, along with improving teaching and service in academic medicine. Factors present in successful programs included identifying goals at program outset, having regular meetings (monthly or more frequently), providing a formal curriculum, using several methods of mentoring, and providing incentives for mentors and mentees. The most frequently mentioned barriers to program success were finding time to meet and providing training for mentors. They concluded that most programs reported descriptive results, and assessments were conducted using locally designed/context specific measures that were not standardized, and in most cases, not checked for reliability and validity. While this was a comprehensive review, it included mentoring for success in teaching and service in addition to research, and it did not compare mentoring strategies for NI, ESI and UMF.

Chua and colleagues [37] conducted a recent scoping review (2000–2019) of 71 articles about mentoring programs in medicine and surgery. They described three categories important to mentoring novice faculty in clinical, educational, and research settings: the host organization (e.g., academic institution), mentoring stages, and evaluation processes. While this was a comprehensive and valuable review, the majority of studies in this review focused on enhancing clinical skills (68%) rather than research skills.

Confirming the disciplines included in the aforementioned literature reviews, a recent network analysis of mentoring literature concluded that five disciplines emerged as leaders in publishing articles about mentoring: academic medicine (e.g., with 29.2% of studies from family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, gerontology, geriatrics, and psychiatry), industrial and organizational psychology (representing 28.7% of studies), education (15.7%), nursing (9.9%) and psychology (8.7%); industrial and organizational psychology and academic medicine have had the most substantial contributions to the literature, as indicated by citations and centrality to the literature [38].

Despite the existing literature on mentoring, little is known about mentoring specifically to advance research in the health-related disciplines, particularly beyond the disciplines of academic medicine and nursing. Most previous reviews are older and have not focused exclusively on mentoring for research development. In addition, an integrative literature review strategy has not been used—which includes additional types of information beyond research articles. A final gap in the existing literature reviews is that to date, no one has attempted to tease out similar and unique barriers and facilitators to research development in NI, ESI and UMF. Given the well-established benefits of mentoring, the ever-changing climate of higher education, the need to review updated contemporary literature, and the lack of an integrative review comparing and synthesizing the literature on research mentoring for NI, ESI and UMF in health-related disciplines, the purpose of this paper was to conduct an integrative literature review to examine the barriers and facilitators to mentoring in health-related research for new and early-stage investigators and underrepresented minority faculty.

2. Materials and Methods

Whittemore and Knafl [39] described a framework for conducting integrative literature reviews. This type of review is unique in that it combines diverse methodologies, includes a variety of types of literature, and is specifically designed to contribute to practice, policy, and theory. We felt that examining a more comprehensive variety of literature would enable us to more fully examine effective mentoring strategies and determine whether mentoring for NI and ESI differs from UMF. Our integrative review framework consisted of five stages: (a) developing the research question, (b) searching the literature, (c) evaluating data, (d) analyzing data, and (e) presenting findings.

2.1. Research Question

Our research question was: what are the barriers and facilitators to mentoring designed to build research capacity in health-related faculty identified as new investigators, early-stage investigators, or underrepresented minority faculty?

2.2. Faculty Categories

In order to fully examine and answer our research question, we felt it was important to clearly define the three (3) faculty categories covered in this review: new investigators (NI), early-stage investigator (ESI), and underrepresented minority faculty (UMF).

New Investigator (NI). A NI, according to the NIH, is “an investigator who has not previously competed successfully for substantial, independent funding from NIH.” (See: early-stage investigator status from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/esi-status.pdf.) Institutes and Centers within the NIH fund NIs according to programmatic and strategic priorities.

Early-Stage Investigator (ESI). The NIH defines an ESI as “a Program Director (PD) or Principal Investigator (PI) who has completed his/her terminal research degree or end of post-graduate clinical training, whichever date is later, within the past 10 years, and who has not previously competed successfully as PD/PI for a substantial NIH independent research award.” (See: early-stage investigator status from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/esi-status.pdf.) Being categorized as an ESI with a fundable score may be advantageous for receiving grants.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) developed NI and ESI categories of investigators to promote the “growth, stability and diversity of the biomedical research workforce.” (See early-stage investigator status from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/esi-status.pdf). From an NIH perspective, some of the benefits of NI and ESI status are that (a) the review process focuses more on the approach than the track record, and less preliminary data are required; (b) the NIH has a program for rapid turnaround for NI and ESI applications, which gives them the opportunity to revise and resubmit their applications more quickly (and may be more appropriate for applications with minor issues, but less appropriate for those seeking more thorough feedback); and (c) some grants with ESIs as the Principal Investigator may have more generous pay lines than for PIs with more experience (https://www.niddk.nih.gov/research-funding/process/apply/new-early-stage-investigators).

Underrepresented Minority Faculty (UMF). Hassouneh and colleagues [40] clarify an important distinction between faculty of color and UMF. Faculty of color include Asians who are minorities in the U.S., but not in health-related fields, notably medicine. UMF include Black or African American, Hispanic or LatinX, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders. Women are underrepresented in certain disciplines, notably academic medicine [41] and STEM fields [42], and sexual minority researchers are underrepresented in scientific leadership positions—even in areas where diseases disproportionately affect them (e.g., HIV-AIDS) [43].

2.3. Literature Search

2.3.1. Search Strategy

In Fall 2020, a rigorous literature search was conducted to identify papers relevant to mentoring NI, ESI, and UMF in health-related disciplines. Databases searched included PsychINFO, CINAHL and PubMed. Boolean connectors AND/OR were used to combine search terms including mentor *, research, health, new investigator *, early stage investigator *, minority faculty, and underrepresented faculty. An advanced search process was utilized to limit publications to peer-reviewed journal articles in English, published between 2010 and 2020. After the aforementioned search, to generate additional papers, reference lists were searched and PubMed links were followed to “Similar Articles.”

2.3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Included in this study were peer-reviewed journal articles published in English from January 2010 to October 2020 related to mentoring to increase research productivity in health-related faculty from the three identified faculty categories. We selected this 11-year period of time to: (a) capture how mentoring has evolved due to recent changes in higher education (e.g., high turnover and shortages in health-related faculty, and increased use of different styles of mentoring), (b) ensure that the most current literature was included and synthesized, and (c) capture relevant data from publications featuring recent federally funded projects designed to enhance mentoring of NI, ESI and UMF. We decided to limit publications to those describing research development in the United States given that our federal research funding structure and processes are unique. In addition to published data-based research studies and reviews, essays, editorials, and presentations converted to manuscripts were included. Non-published work, including theses and dissertations, and conference proceedings were excluded.

3. Results

3.1. Summary of Search Results

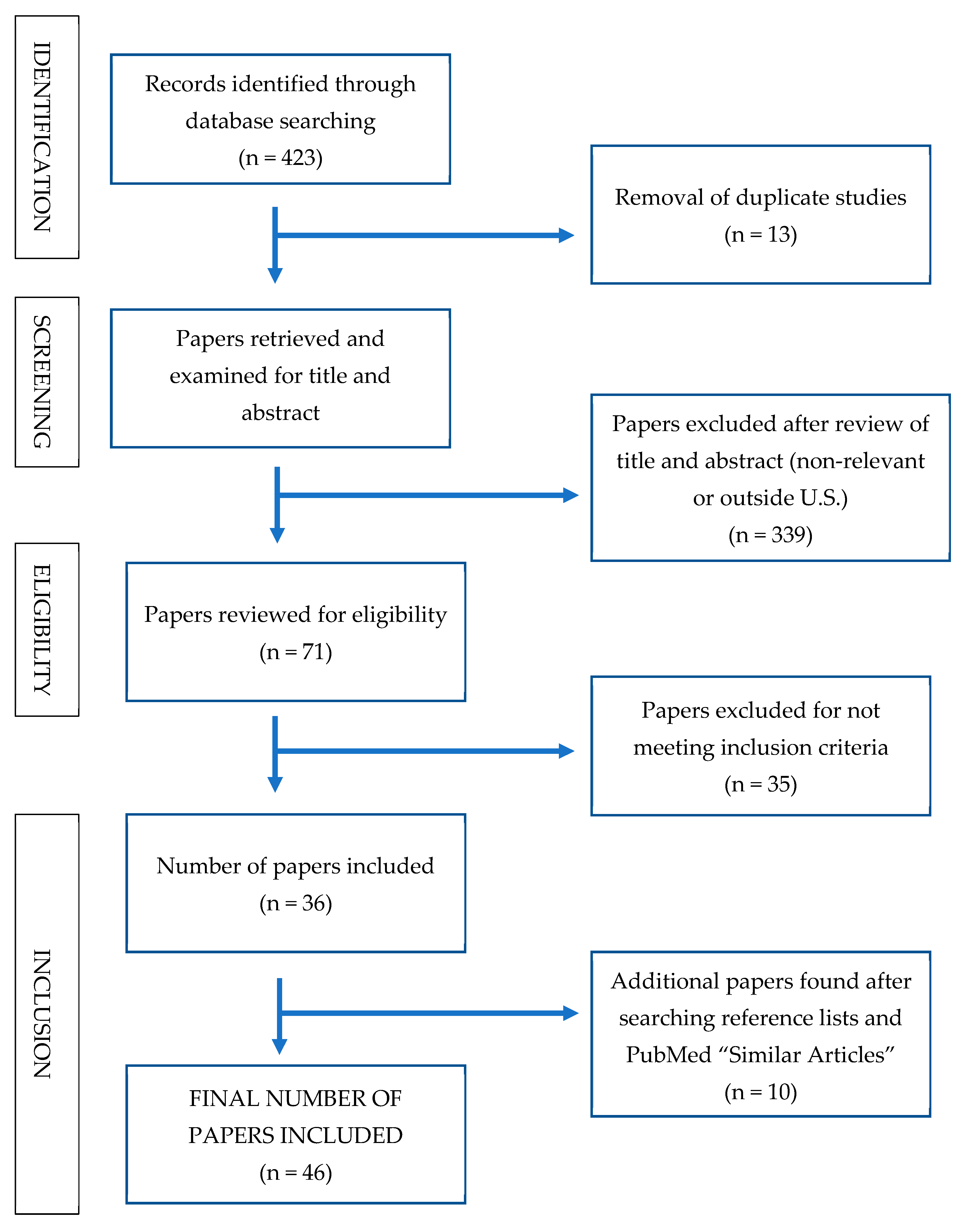

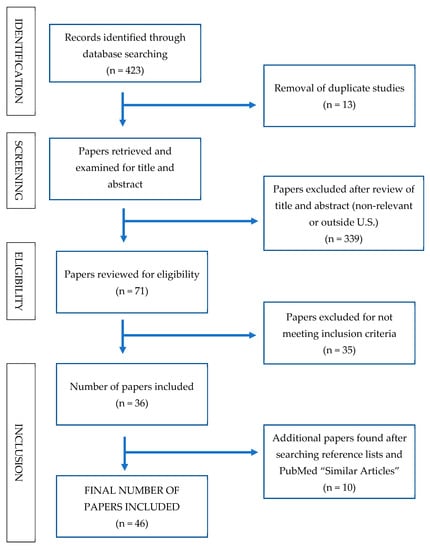

The database searches generated 423 records. Once duplicates were removed, 410 studies remained. Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of papers using the inclusion and exclusion criteria and 339 papers were removed, leaving 71 papers to be reviewed for eligibility. Of the 71 studies reviewed, 35 did not meet inclusion criteria leaving 36 papers. From the remaining 36 papers, references lists were scanned for additional studies, and “Similar Articles” were searched in PubMed. One (1) NIH workshop on mentoring was found. As a result of these expanded search strategies, 10 additional resources were added, resulting in a total of 46 papers. A summary of the decision trail used to locate and select studies for this paper is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Search strategy and decision trail for selecting included studies.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 1 provides an overall summary table for the 46 papers reviewed, with first authors listed in alphabetical order (identified by reference number), followed by publication year, study design, purpose, methods, participants, additional pertinent results, barriers and facilitators of research (with a focus on mentoring), limitations, and recommended directions for future research.

Table 1.

Summary of studies examining barriers and facilitators to research in health-related faculty categorized as NI, ESI, or UMF.

After completing this review, several important trends in the literature were noted. The health-related discipline most frequently represented in this search was academic medicine (including a variety of specialized medical fields). There were a handful of studies examining mentoring in faculty from behavioral and mental health, nursing, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and public health. The academic content areas in which scholars were most frequently mentored included unspecified or general health (n = 21), HIV/AIDS (n = 5), and health equity or health disparities (n = 4); topics studied less frequently included aging, behavioral or mental health, cancer, obesity and sleep.

Mentoring of faculty in medical and health-related academic units occurred in a variety of formats, including in dyads or constellations, or with peers or groups, and either face to face or via distance (i.e., telementoring). Most papers recommended having multiple mentors (vs. the dyadic approach), and many advocated for assessing baseline research skills and re-evaluating progress regularly [47,56,68,70,84,87].

More than half of the studies (n = 27) examined enhancing research capacity in UMF, and a variety of research designs (e.g., descriptive, longitudinal, qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods) were utilized to explore ways in which to enhance research productivity. Although we did not include a search term for “women” as an underrepresented subgroup, several of the studies included a majority of women [49,51,53,59,60,61,63,64,65,81,83,87]. Two of the studies we included exclusively surveyed women [52,84]. We included studies that included a majority of women or reviews focused exclusively on women as they are considered underrepresented in the male-dominated field of academic medicine. Unique aspects of mentoring women were mentioned when they occurred. Just over one-third of the papers (n = 18) examined research facilitators in NI and ESI, without significant representation of UMF.

The types of institutions in which the participants were employed varied. Most faculty were from a mix of academic institutions, and results were summarized without disaggregating information about their academic institution. Five studies examined the perspective of NI and ESI faculty in research-oriented institutions, with some exclusively surveying UMF [57,88], and some including a percentage of UMF (10–62%), but not disaggregating findings by race/ethnicity or gender [48,59,83]. Two studies examined research success from the perspective of faculty employed at a minority serving institution (MSI) [44,87]. Three studies described advancing research capacity through partnerships between research-oriented (RO) institutions and MSIs [45,49,71].

In the next sections, we summarize barriers and facilitators of developing research capacity in NI, ESI and UMF in health-related fields. Barriers were both individual (Section 3.3.1.) and institutional (Section 3.3.2.). Individual facilitators were subdivided into technical skills (Section 3.4.1.), interpersonal skills (Section 3.4.2.), and personal skills (Section 3.4.3.), and institutional facilitators were combined and summarized (Section 3.4.4.).

3.3. Barriers to Developing Research Capacity

In an effort to identify overlapping and unique barriers to developing research capacity in NI, ESI, and UMF, a concept matrix mapping exercise was conducted. Barriers were divided into individual and institutional factors as Manson [67] noted the importance of considering not only individual constructs, but also environmental (i.e., institutional) constructs.

3.3.1. Individual Barriers to Research Success

Table 2 contains a summary of individual barriers to research success. Individual barriers that appeared in all three (3) faculty categories were a lack of time (n = 5) [52,53,57,66,69] and finding work–life balance (n = 4) [58,69,76,83].

Table 2.

Summary of individual barriers to research success for new or early-stage investigators and/or underrepresented minority faculty.

The most frequently occurring individual barriers for UMF were related to bias and discrimination (n = 5) [44,45,60,65,77] and isolation (n = 5) [45,60,65,86,88]. Not included in the summary table, yet still worth mentioning as a barrier for UMF (both ethnic minorities and women), is the barrier of differential power dynamics (n = 3), which occurs if the mentor–mentee relationship is hierarchical [52], if the mentor does not value the skill set or research area of the mentee [65], or if institutional and mentor values differ from the mentee [88]. Two studies mentioned financial barriers to success including a high cost of living combined with student loan debt, and childcare needs [76,86].

3.3.2. Institutional Barriers to Research Success

Table 3 contains a summary of institutional barriers to research success in NI, ESI or UMF. Institutional barriers were more frequently mentioned than individual barriers. The most frequently occurring institutional barrier for NI, ESI and UMF was a lack of mentors (n = 12) [45,46,52,55,63,64,66,67,77,86,88]. Especially lacking were mentors who matched the area of study, expertise, diversity, or research deficits of the mentee. Lack of access to resources was the second most frequently mentioned institutional barrier for all faculty categories (n = 9) [44,45,46,48,55,64,65,67,77]. Resources mentioned include research help, teaching buyout, and networks. The third most frequently mentioned institutional barrier for NI, ESI and UMF was a heavy teaching and service load (n = 7) [44,45,46,55,64,76].

Table 3.

Summary of institutional barriers to research success for new or early-stage investigators and/or underrepresented faculty.

UMF were significantly impacted by implicit or explicit bias against or devaluation of an academic degree, experience or expertise (n = 6) [44,45,57,65,77,88]. Not included in Table 3, but worth mentioning as a barrier for UMF, was a lack of long-term or succession programming for their mentoring programs [16,77,86], and not knowing institution-specific factors that influence success (e.g., promotion and tenure guidelines) [77,79].

3.4. Facilitators for Developing Research Capacity

Knowing barriers to research success is helpful, but it is also important to know facilitators in order to overcome barriers and develop corrective strategies. To identify overlapping and unique facilitators for developing research capacity in NI, ESI and UMF, additional concept matrix mapping exercises were conducted. Individual facilitators, which were mentioned more frequently than individual barriers, were further subdivided into technical, interpersonal, and personal skills. Technical facilitators are academic skills (e.g., writing, synthesis, presentations, content knowledge) that early career and UMF faculty have partially developed during their education, but more development is needed to continue to advance a career. Interpersonal skills are those related to the ability to effectively interact and connect with others (e.g., networking, collaborating). Personal skills are traits within an individual, related to success in research, that can be developed with practice and experience (e.g., accountability, leadership, time management, resilience and grit). Institutional facilitators are factors within an institution where a faculty member is employed that boost research success (e.g., access to mentoring, professional development opportunities, workload assigned to research).

3.4.1. Technical Skills That Facilitate Research Capacity

Table 4 contains a summary of technical facilitators that can enhance research productivity for NI, ESI and UMF. The most frequently mentioned technical skills for NI, ESI and UMF, related to research success, were writing manuscripts and grants (n = 17), followed by analytical skills (synthesis and statistics, n = 4). Analytical skills are vitally important for writing manuscripts and grants, but they are rarely separated from writing in the mentoring literature reviewed. Presentation skills, related to public speaking and thinking on your feet, were also mentioned (n = 4) [48,59,65,79]. Two technical skills mentioned less frequently by NI, ESI and UMF, but worth including as facilitators due to their impact on research success, are knowledge about responsible conduct of research [62,72,73] and content knowledge [54,72]. There were no technical facilitators to research success unique to any faculty category—all were consistently mentioned for NI, ESI and UMF.

Table 4.

Summary of technical skills recommended for new faculty, early career faculty, and underrepresented minority faculty.

3.4.2. Interpersonal Skills That Facilitate Research Success

Table 5 summarizes interpersonal skills that are important for growing research capacity. The most frequently mentioned areas in this category that contribute to research success for NI, ESI and UMF are finding productive collaborators (n = 33) and networking (n = 28). Also important are managing data, projects and teams (n = 7) [47,48,62,75,79,87,88], and learning organizational dynamics and navigating political traps (n = 6) [46,63,65,73,76,88]. An interpersonal skill not included in the table, but mentioned in some papers is responding to feedback (n = 5) [43,46,47,78,88]. Compared to being defensive about feedback, responding appropriately can facilitate continued corrective mentoring, and result in more published papers and funded grants.

Table 5.

Summary of interpersonal skills recommended for new faculty, early career faculty, and underrepresented minority faculty.

One important interpersonal skill mentioned in a large number of the papers on mentoring research success in UMF was advocacy for diversity and cultural humility [55,57,60,62,65,70,71,72,77,80,87,88]. Berget and colleagues [45] described “survival skills workshops” that included creating a sense of community within a research discipline; effectively articulating benefits of CBPR and community partnerships to peers and administrators; and appropriately saying no if asked to participate in too many minority-related service assignments. Having frank discussions about family–work–life balance, time management, and building coalitions of internal and external supporters were also deemed important. Flores et al. [62] described essential strategies for research success for UMF, which included advocating for diversity and cultural humility by debriefing often with colleagues, handling implicit bias professionally, and responding to bias immediately (vs. cumulatively). Both Flores et al. [62] and Jean-Louis et al. [65] mentioned the importance of failing productively and having a safe space to fail.

3.4.3. Personal Skills That Facilitate Research Success

Personal skills needed for success in a research career are summarized in Table 6. The most frequently mentioned personal skill for NI, ESI and UMF is accountability (n = 17), followed by career planning (n = 14). Mentioned less frequently is leadership [47,59,62], resilience and grit [47,62], and ethical behavior (e.g., treatment of human subjects, data collection and management, citations, authorship) [47,72]. There were no personal facilitators unique to research success—all were consistently mentioned for NI, ESI and UMF.

Table 6.

Summary of personal skills recommended for new faculty, early career faculty, and underrepresented minority faculty.

3.4.4. Institutional Facilitators of Research Success

Table 7 presents institutional facilitators that are essential for research success. The institutional facilitator mentioned most frequently for NI, ESI and UMF was access to expertise and mentoring (n = 45), followed by professional development opportunities (n = 38), science culture (n = 17), workload assigned to research (n = 16), and funding (n = 14). Five papers recommended pre-screening research skills to determine the best mentors and mentoring strategies for each mentee [47,56,68,70,84], and one paper recommended this strategy for UMF [38]. Knowing the promotion and tenure standards, which was mentioned, but not included in the table, was considered an important institutional facilitator by Blanchard et al. [43], Feldman et al. [59], Flores et al. [60], and Martina et al. [68].

Table 7.

Summary of institutional facilitators recommended for new faculty, early career faculty, and underrepresented minority faculty.

Sixteen papers advocated for developing mentoring strategies leading to cultural humility and a culturally responsive institution, and of these, 13 included scholars of color in their sample [44,46,53,55,57,58,60,61,62,65,71,77,88]—one was a review about women in higher education [52], and two were focused on NI and ESI [67,70].

4. Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to conduct an integrative literature review to examine the barriers and facilitators to mentoring in health-related research, particularly for NI, ESI or UMF. One important general finding of this integrative literature review was that health-related research should continue to expand the disciplines and content areas in which mentoring studies are conducted. We reported that the majority of mentoring studies included in this review focused on academic medicine, which is similar to findings reported by Lefebvre, Bloom, and Loughead [38]. Although we did not search for any health-related disciplines by name, we did use “health” as a search term, which garnered studies from other disciplines. Given differences in workloads, accreditation requirements, and institutions, it is important to continue to study mentoring in other health-related academic disciplines, across academic ranks (including mid- and late-career faculty), across intersectionality (e.g., minority women), and across various types of academic institutions (e.g., minority serving institution, research-oriented institution or emerging research institution).

A second general finding was that mentoring occurs in a variety of formats, and researchers increasingly recommend pre-assessing research skills so that mentoring teams can be formed, which can help NI, ESI and UMF receive support in as many desired areas as needed. We noted that numerous types of mentor–mentee matching strategies were used including dyads, peers, groups, constellations or groups, and telementoring. Prior researchers [27,89,90] have categorized formal mentoring similarly.

We conclude that both formal and informal mentoring are important for research development. Formal mentoring systems match mentors and mentees based on personality, culture, goals and expectations [90], and they typically have planned, regular activities that consider developmental stages of the mentees [91]. Informal mentoring, which is unstructured, consists of mentees discussing career strategies and aspirations, along with professional, personal and psychosocial issues, with mentors [92]. Huggett and colleagues [93] concluded that informal mentoring is important for career satisfaction and formal mentoring is important for enhancing academic productivity. Some programs recommend discipline- or department-specific mentors [94,95], while others advocate for cross-departmental mentoring, which helps with meeting a variety of research development needs [53,90] and with confidentiality [96]. Brown, Daly and Leong [95] advocated for a “developmental model of mentoring,” whereby different mentoring strategies are used for each level of researcher in psychology (e.g., undergraduate and graduate student, post-doc, and junior faculty) and for women and ethnically diverse researchers.

4.1. Individual and Institutional Barriers to Research Mentoring

The most prominent individual barriers to mentoring for research success, which were mentioned for NI, ESI and UMF, were a lack of time, and finding work–life balance. Due to the increasing expectation that faculty members do more with less, it is unlikely that time will be removed as a barrier to research mentoring. The goal then, should be to achieve maximal benefits in minimal time. This can be done by pre-assessing NI, ESI and UMF for research readiness, focusing heavily on research development areas identified in the needs assessment, and sharing the mentoring load among multiple mentors. Given that potential research mentors are also coping with increased demands, providing training and incentives (e.g., workload credit, authorship, or renumeration) for mentors may more effectively incentivize them to participate.

It is disconcerting that unique individual and institutional barriers are still present for UMF. The most prominent barriers reported by individual UMF were related to bias and discrimination. Bias can include negative experiences with hiring, promotion and tenure evaluations, or manuscript/grant reviews, or it can involve perceived decreased value of degrees from certain institutions. Individual and institutional barriers are intimately interrelated for UMF, such that when they encounter institutional barriers to research success, it exacerbates individual barriers such as perceived racism. For example, when UMF are hired into predominately white institutions of higher education, they report that they experience overt and covert racism, their work is marginalized, and their contributions are undervalued; in addition, UMF are often asked to participate in activities that will not advance their careers (i.e., serve as minority representatives on committees), prompting some UMF to report feeling like “institutional mascots” [97]. As a result of these experiences, some UMF struggle with a sense of isolation (i.e., “being the only one”) or “imposter syndrome,” meaning that they feel that they do not belong in a specific setting [88]. Others report “unpleasant peer interactions” that isolate them academically and socially, and may prevent them from “accumulating social capital” [88]. A lack of mentoring has left many UMF feeling like they did not have the information and guidance they needed to succeed in networking (internally and externally) and meeting tenure-and-promotion expectations [88,90,98]. When these issues are combined, many UMF experience work stress in the academy, which in turn, can contribute to stress-related health problems [88,97].

Another individual barrier for UMF is coping with differential mentoring power dynamics. The concept of “differential power dynamics,” which appeared in papers summarizing concerns of minorities [65,88] and women [52], refers to the use of a hierarchical model of mentoring, whereby the mentor holds the rank and power, and the mentee is required to follow the direction of the mentor—whether or not it is desired by the mentee. Ideally, mentoring relationships are bi-directional, whereby both the mentor and mentee receive benefits. Mentoring opportunities and settings can be structured in ways that minimize power differentials and encourage the exchange of ideas, mutual responsibility, and flexible options for the mentor and mentee.

The most frequently mentioned institutional barrier to research mentoring that overlapped across NI, ESI and UMF was a lack of mentors. Mentors may be less willing to participate if they are not receiving workload credit for mentoring or if the experience is not mutually beneficial. Additionally, prior research has reported that some institutions (e.g., predominately white institutions) lack diverse faculty who can mentor [88], and some academic disciplines (e.g., medicine) lack women and diverse faculty who can mentor [41]. Sometimes, mentors are assigned without knowledge of an academic discipline or method of collecting data. Pre-assessing mentoring needs and then assigning mentoring teams may help offset this challenge. Mentoring needs assessments can be structured in a way that focuses on pairing mentees with mentors based on faculty strengths, previous accomplishments, and interests in ways that maximize information sharing to help with the formation of mentoring teams.

Another barrier mentioned was a lack of resources, such as access to journals, insufficient funds for research costs (pilot data collection or research help), inadequate buyout from teaching, or reduced access to research networks. Related to a lack of resources is a heavy teaching and service load, especially for those working at minority serving institutions [44], juggling clinical responsibilities in addition to teaching and research [76], or serving on various committees to represent their minority group interests [45].

4.2. Individual (Technical, Interpersonal, and Personal) Facilitators of Research Mentoring

Facilitators of research mentoring, which overlapped in NI, ESI and UMF at the individual level, were technical skills such as help with writing manuscripts and grants, statistics and synthesis, or oral presentations, interpersonal skills, such as help with finding collaborators, networking, managing teams, and navigating organizational dynamics, and personal skills such as holding mentor and mentee accountable and helping with career planning. Not surprisingly, these individual mentoring skills are offered by most mentoring workshops and programs that seek to help investigators at the individual level.

4.3. Institutional Facilitators of Mentoring for Research Success

The most frequently mentioned institutional facilitators of research success for all faculty categories included access to expertise and mentoring, professional development opportunities, science culture, workload assigned to research, and funding. Most of these needs appeared first as barriers, and now as facilitators.

Advocacy for diversity and cultural humility were interpersonal research facilitators specific to UMF. Advocating for diversity can include insisting that applicant pools and subjects for research studies are diverse, recruiting diverse individuals to serve on faculty and in other important roles, and supporting diverse individuals who speak for specific types of candidates and research agendas, or speak out against the minority tax (e.g., being asked to do twice as much service to “represent” an underrepresented group) [99]. Cultural competence refers to “mastering a theoretically finite body of knowledge,” whereas the newer term, cultural humility refers to “a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, redressing power imbalances that occur throughout the academy, and developing mutually beneficial and non-paternalistic clinical and advocacy partnerships with communities” [99]. Interpersonal diversity-oriented strategies can be reinforced at the institutional level by training mentors to utilize culturally responsive mentoring strategies and advocate for a culturally responsive institutional climate. Advocacy for diversity and cultural humility can go a long way toward addressing both the individual and institutional barriers that UMF feel related to bias and discrimination. Educating all faculty about implicit bias and cultural humility, and discussing the importance of advocating for diversity and understanding ethnically relevant research methodology could prevent UMF from feeling like “tokens” or “ethnic specialists.” These activities may also lessen some of the isolation typically felt by UMF because the responsibility to discuss equity, inclusion and diversity will fall upon more faculty colleagues—not just the UMF employed at a university.

Universities should be a place where culture is discussed, conceptualized, and valued [20], and where individuals authentically address bias, stereotype threats, and cultural ignorance [59]. Emphasizing the importance of cultural humility requires individuals to self-evaluate and self-critique, advocate against power imbalances, and develop partnerships with people and groups who advocate for others who are different from themselves [100].

Interestingly, five of the six studies that recommended pre-assessing faculty for research readiness were specific to NI and ESI; only one mentioned pre-assessing the research readiness of UMF. This presents an opportunity for institutions of higher education to develop UMF-specific mentoring programs that conduct needs assessments for research development, match multiple mentors with a mentee, regularly re-assess, and measure outcomes.

4.4. Limitations

Despite the plethora of findings reported, this study was not without limitations. Studies included were relevant to NI, ESI and UMF, limited to an 11-year time period, written in the English language, and all were from the United States from health-related disciplines. While some of our results may be generalizable to other disciplines or other countries, caution is urged as this paper is focused on faculty from the health disciplines, during a specific time period of their career, within NI, ESI and UMF utilizing data from institutions of higher education in the United States. This review did not include theses or dissertations or studies examining research mentoring in scholars with disabilities, or those who come low SES backgrounds. We were not able to locate specific literature that has examined growing research productivity in those categories of underrepresented faculty. Additionally, we were not able to distinguish between mentoring needs of subpopulations of UMF. For example, needs of an African American scholar may differ from those of a Hispanic or Native American scholar. The literature did not delve more deeply into this very important issue, so we were not able to explore this topic. Another limitation is that terms related to mentoring and measures of impact are not standardized across studies, which may conflate findings. The use of an integrative literature review technique is qualitative in nature, and does not include effect sizes or other quantitative data that might inform the reader about the magnitude of effects of certain mentoring behaviors. Finally, although this review was comprehensive, some articles related to this topic may have been unintentionally omitted.

4.5. Future Directions

Our integrative review of the literature uncovered several areas that would benefit from future research. First, the mentoring literature could be advanced by comparing mentoring at all career stages (e.g., early, mid and late career) and making recommendations for best practices at each stage [85]. Second, there is a need to expand studies examining mentoring for research development beyond the U.S. Nowell et al. [21] reviewed literature on the outcomes of mentoring nursing faculty from the U.S., Canada, and Australia, and Chua et al. [37] examined three themes (host organization, mentoring stages and evaluation) in mentoring programs from the U.S., the UK, Canada, and other countries. However, even though studies from other countries have been included in previous reviews, a comparison of how research mentoring programs differ across countries has not been conducted. From a critical analysis of worldwide research mentoring programs, policy recommendations can be made to enhance research productivity—either at the individual or institutional level. Relatedly, more research should be conducted to examine the impact of cultural or ethnic background on research development. Specifically, Espino and Zambrana [57] noted that when the research productivity of underrepresented groups has been studied, Native Americans, those who are differently-abled, LGBTQ, or those from disadvantaged backgrounds (e.g., homeless, foster care, first-generation college graduates, or low SES) are rarely included. Further examining how underrepresented groups may differ from one another in mentoring needs should also be considered. Thirdly, little research has been conducted to test the effectiveness of different types of mentoring (e.g., dyads, groups, peers, and telementoring) [89]. Fourth, we need to expand the types of studies conducted beyond descriptive, cross-sectional and qualitative, to include more longitudinal, prospective and experimental/intervention designs [56,82]. Fifth, scholars could expand the insights provided by reporting more comprehensive details on institutional and departmental characteristics and differences between mentees, mentors, and mentoring programs, as well as reporting on intersectional characteristics that define a faculty member and may impact career success (e.g., LGBTQ, differently-abled, military, first-generation college graduates, or low SES backgrounds). Sixth, taken as a whole body of literature, only a handful of studies included and described a theoretical framework [41,44,48,69,77]. Literature reviews by Doyle et al. [54] and Pfund et al. [72] expressed the need for continuing to advance the theoretical framework for mentoring in the academy. As a seventh direction for future research, there is a need to standardize mentoring terminology and evaluation methods [54,72,74,89] and continue to examine the most important variables (e.g., mediators) for enhancing mentoring. For example, Thorpe et al. [83] emphasized that there is a strong relationship between academic self-efficacy (i.e., grant writing self-efficacy) and academic success [47], but additional research is needed. Although two reviews on assessing mentoring success have been published [101,102] it is clear that more research is needed to discern which questionnaires, surveys, interview questions, or other strategies should be used to assess the success of specific parts of mentoring programs (e.g., mentor and mentee success and program success). An eighth recommendation is to examine not only the benefits, barriers and facilitators of mentorship for mentees, but also appropriate content and strategies for training mentors [89], and how that relates to program success. A ninth recommendation for future study is to continue to examine how to pair mentors and mentees for research success, as was discussed in Huggett et al., [93] and Huskins et al. [103]. To date, researchers have recommended mentor–mentee matching based on educational background, professional experience, teaching or research assignments, professional interests, and mentee goals [89]. However, studies have failed to compare different strategies for matching mentees with mentors to determine whether different methods of matching result in different outcomes. Finally, the ultimate study design might examine which types of mentoring (dyads, peers, etc.) and which modes of mentoring (formal, informal), as moderated by gender, ethnicity or intersectionality, and mediated by academic environment and career stage, have the most impact on academic success [72,77].

5. Conclusions

In this study, we sought to answer the research question: “What are the barriers and facilitators to mentoring designed to build research capacity in health-related faculty identified as NI, ESI or UMF?” Our study is unique in that it expanded health-related disciplines previously examined beyond nursing and academic medicine using an integrative literature review. It also examined individual and institutional barriers and facilitators to research development that were similar and unique in NI, ESI and UMF. Many individual and institutional research barriers and benefits were consistent across faculty subgroups, but there are some that are institution-based or unique to UMF. Specifically, the most frequently mentioned individual barriers were lack of time and finding work–life balance. UMF expressed concern about the impact of bias, discrimination and isolation on research productivity. Individual facilitators should target the aforementioned barriers, and build skills in writing/synthesis, networking, accountability, leadership, time management and resilience/grit. Institutional barriers include a lack of mentors, access to resources, and a heavy teaching/service load. Institutional facilitators should seek to decrease the aforementioned barriers, and increase access to mentoring, professional development, and workload assigned to teaching. Advocacy for diversity and cultural humility are important career facilitators for all faculty, and offering training at the institutional level establishes the importance of these strategies for career success. Mentoring, if done systematically with a focus on individual and institutional barriers and facilitators, using evidence-based practices, should have a positive effect on the success of NI, ESI and UMF. Stoff [79] purports that increasing diversity in research personnel will lead to decreased health disparities and increased health equity among underserved populations; in addition, diverse teams capitalize on innovation and bring different perspectives, creativity and experiences to address complex scientific problems. The bottom line is that if diverse health-related faculty are successful in research, this should have a positive effect on health behavior and health promotion, and it should lessen the burden of disease in our most vulnerable populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B.R., T.S.L., A.L.S., H.A.W., and J.A.B.; methodology, L.B.R.; formal analysis, L.B.R.; investigation, L.B.R. and T.S.L.; data curation, L.B.R. and T.S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.R.; writing—review and editing, T.S.L., A.L.S., H.A.W., and J.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by an NIMHD center grant to the Southwest Health Equity Research Collaborative at Northern Arizona University (U54MD012388).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, because it was a literature review, and no new data were collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not necessary because previous researchers collected the data synthesized in this literature review.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cote, J.E.; Allahar, A.L. Lowering Higher Education: The Rise of Corporate Universities and the Fall of Liberal Education; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grawe, N.D. Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education; Johns Hopkins Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenstyk, G. American Higher Education in Crisis? What Everyone Needs to Know; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, M.J. Post-COVID-19 threats to higher education. Enroll. Manag. Rep. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucklin, B.A.; Valley, M.; Welch, C.; Tran, Z.V.; Lowenstein, S.R. Predictors of early faculty attrition at one academic medical center. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Association of University Professors (AAUP). Tenure. Available online: https://www.aaup.org/issues/tenure (accessed on 26 December 2020).

- Nikaj, S.; Roychowdhury, D.; Lund, P.K.; Matthews, M.; Pearson, K. Examining trends in the diversity of the U.S. National Institutes of Health participating and funded workforce. FASEB J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, I.; Bailey, L.O.; Bakos, A.D.; Springfield, S.A. The continuing umbrella of research experiences (CURE): A model for training underserved scientists in cancer research. J. Cancer Educ. 2011, 26, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosoko-Lasaki, O.; Sonnino, R.E.; Voytko, M.L. Mentoring for women and underrepresented minority faculty and students: Experience at two institutions of higher education. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2006, 98, 1449–1459. [Google Scholar]

- TIAA Institute. Taking the Measure of Faculty Diversity. Available online: https://www.tiaainstitute.org/sites/default/files/presentations/2017-02/taking_the_measure_of_faculty_diversity.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). Populations Underrepresented in the Extramural Scientific Workforce. Available online: https://diversity.nih.gov/about-us/population-underrepresented (accessed on 27 December 2020).

- Brown, S.E.; Takahashi, K.; Roberts, K.D. Mentoring individuals with disabilities in postsecondary education: A review of the literature. J. Postsec. Educ. Disabil. 2010, 23, 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Haeger, H.; Fresquez, C. Mentoring for inclusion: The impact of mentoring on undergraduate researchers in the sciences. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2016, 15, ar36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, D.A.; Gyurko, C.C. The global nursing faculty shortage: Status and solutions for change. J. Nurs. Sch. 2013, 45, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, A.P.; Smith, N.; Gulish, A. Nursing: A closer look at workforce opportunities, education, and wages. Am. J. Med. Res. 2018, 5, 29–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girod, S.C.; Fassiotto, M.; Menorca, R.; Etzkowitz, H.; Wren, S.M. Reasons for faculty departures from an academic medical center: A survey and comparison across faculty lines. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, B.A.; Dilmore, T.C.; Switzer, G.E.; Bryce, C.L.; Seltzer, D.L.; Li, J.; Landsittel, D.P.; Kapoor, W.N.; Rubio, D.M. Burnout among early career clinical investigators. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2010, 3, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. Introduction to Mentoring: A Guide for Mentors and Mentees. Available online: https://www.apa.org/education/grad/mentoring (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Mullen, C.A.; Hutinger, J.L. At the tipping point? Role of formal faculty mentoring in changing university research cultures. J. In-Service Educ. 2008, 34, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, M.P.; Zimmerman, K.M. Identifying components of success within health sciences-focused mentoring programs through a review of the literature. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 6976. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30894774/ (accessed on 28 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.; Norris, J.M.; Mrklas, K.; White, D.E. Mixed methods systematic review exploring mentorship outcomes in nursing academia. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 73, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, T.D.; Eby, L.T.; Poteet, M.L.; Lentz, E.; Lima, L. Career benefits associated with mentoring for proteges: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.T.; Allen, T.D.; Evans, S.C.; Ng, T.; DuBois, D. Does mentoring matter? A multidisciplinary meta-analysis comparing mentored and non-mentored individuals. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 72, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.T.; Allen, T.D.; Hoffman, B.J.; Baranik, L.E.; Sauer, J.B.; Baldwin, S.; Morrison, M.A.; Kinkade, K.M.; Maher, C.P.; Curtis, S.; et al. An interdisciplinary meta-analysis of the potential antecedents, correlates and consequences of protégé perceptions of mentoring. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 441–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransdell, L.B.; Nguyen, N.; Hums, M.; Clark, M.; Williams, S.B. Voices from the field: Perspectives of U.S. Kinesiology chairs on opportunities, challenges, and the role of mentoring in the chair position. Quest 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransdell, L.B. Women as leaders in kinesiology and beyond: Strategies for breaking through the glass obstacles. Quest 2014, 66, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, S. Initiative of a mentoring program: Mentoring invisible nurse faculty. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2020, 15, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.R. Pursuing personal passion: Learner-centered research mentoring. Fam. Med. 2018, 50, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokelainen, M.; Turunen, H.; Tossavainen, K.; Jamookeeah, D.; Coco, K. A systematic review of mentoring nursing students in clinical placements. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, A.M.; Coyle, J.; Pope, R.; Boxall, D.; Nancarrow, S.A.; Young, J. Supervision, support and mentoring interventions for health practitioners in rural and remote contexts: An integrative review and thematic synthesis of the literature to identify mechanisms for successful outcomes. Hum. Resour. Health 2014, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sng, J.H.; Pei, Y.; Toh, Y.P.; Peh, T.Y.; Neo, S.H.; Krishna, L.K.R. Mentoring relationships between senior physicians and junior doctors and/or medical students: A thematic review. Med. Teach. 2017, 39, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, J.; Garrod, T.; Talley, N.H.; Tebbutt, C.; Churchill, J.; Farmer, E.; Baur, L.; Smith, J.A. The clinical academic workforce in Australia and New Zealand: Report on the second binational summit to implement a sustainable training pathway. Intern. Med. J. 2017, 47, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, E.; Price, C.; Day, J. An integrative review of engaging clinical nurses in nursing research. J. Nurs. Sch. 2016, 48, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budderberg-Fischer, B.; Herta, K.D. Formal mentoring programmes for medical students and doctors—A review of the Medline literature. Med. Teach. 2006, 28, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.W.; Keefe, M.R. Building research competence in nursing through mentoring. J. Nurs. Sch. 2002, 34, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.T.; Satterfield, C.A.; Blackard, J.T. Essential competencies in global health research for medical trainees: A narrative review. Med. Teach. 2017, 39, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, W.J.; Shuen, C.W.; Lee, F.Q.H.; Koh, E.Y.H.; Tohn, Y.P.; Mason, S.; Krishna, L.K.R. Structuring mentoring in medicine and surgery. A systematic scoping review of mentoring programs between 2000 and 2019. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2020, 40, 158–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, J.S.; Bloom, G.A.; Loughead, T.M. A citation network analysis of career mentoring across disciplines: A roadmap for mentoring research in sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassouneh, D.; Lutz, K.F.; Beckett, A.K.; Junkins, E.P.; Horton, L.L. The experiences of underrepresented minority faculty in schools of medicine. Med. Educ. Online 2014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coe, C.; Piggott, C.; Davis, A.; Hall, M.N.; Goodell, K.; Joo, P.; South-Paul, J.E. Leadership pathways in academic family medicine: Focus on underrepresented minorities and women. Fam. Med. 2020, 52, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.J. Gender disparity in STEM disciplines: A study of faculty attrition and turnover intentions. Res. High. Educ. 2008, 49, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, S.A.; Rivers, R.; Martinez, W.; Agodoa, L. Building the network of minority health research investigators: A novel program to enhance leadership and success of underrepresented minorities in biomedical research. Ethn. Dis. 2019, 29 (Suppl. 1), 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beech, B.M.; Norris, K.C.; Thorpe, R.J.; Heitman, E.; Marino, B. Conversation Cafés and Conceptual framework formation for research training and mentoring of underrepresented faculty at Historically Black Colleges and Universities: Obesity Health Disparities (OHD) PRIDE program. Ethn. Dis. 2020, 30, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berget, R.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Ricci, E.M.; Quinn, S.C.; Mawson, A.R.; Payton, M.; Thomas, S.B.; Berget, R.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Ricci, E.M.; et al. A plan to facilitate the early career development of minority scholars in the health sciences. Soc. Work Public Health 2010, 25, 572–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, R.A.; Dyer, T.; Watson, C.C.; Scott, H. Navigating opportunities, learning and potential threats: Mentee perspectives on mentoring in HIV research. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20 (Suppl. 2), 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buist, D.S.; Field, T.S.; Banegas, M.P.; Clancy, H.A.; Doria-Rose, V.P.; Epstein, M.M.; Greenlee, R.T.; McDonald, S.; Nichols, H.B.; Pawloski, P.A.; et al. Training in the conduct of population-based multi-site and multi-disciplinary studies: The Cancer Research Network’s scholars program. J. Cancer Educ. 2017, 32, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byington, C.L.; Keenan, H.; Phillips, J.D.; Childs, R.; Wachs, E.; Berzins, M.A.; Clark, K.; Torres, M.K.; Abramson, J.; Lee, V.; et al. A matrix mentoring model that effectively supports clinical and translational scientists and increases inclusion in biomedical research: Lessons from the University of Utah. Acad. Med. 2016, 91, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.G.; Leibowitz, M.J.; Murray, S.A.; Burgess, D.; Denetclaw, W.F.; Carrero-Martinez, F.A.; Asai Schinske, D.J. Partnered research experiences for junior faculty at minority-serving institutions enhance professional success. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2013, 12, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.G.; Sherman, A.E.; Kiet, T.K.; Kapp, D.S.; Osann, K.; Chen, L.M.; O’Sullivan, P.S.; Chan, J.K. Characteristics of success in mentoring and research productivity—A case-control study of academic centers. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 125, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comeau, D.C.; Escoffery, C.; Freedman, A.; Ziegler, T.R.; Blumberg, H.M. Improving clinical and translational research training: A qualitative evaluation of the Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute (ACTSI) KL2-mentored research scholars program. J. Investig. Med. 2017, 65, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, M.; Lee, S.; Bridgman, H.; Thapa, D.K.; Cleary, M.; Kornhaber, R. Benefits, barriers and enablers of mentoring female health academics: An integrative review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, T.H.; Borrego, M.E.; Page-Reeves, J. Increasing the number of underrepresented minority behavioral health researchers partnering with underresourced communities: Lessons learned from a pilot research project program. Health Promot. Pract. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, N.W.; Lachter, L.G.; Jacobs, K. Scoping review of mentoring research in the occupational therapy literature, 2002–2018. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2019, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, G.A.; Lockett, A.; Villegas, L.R.; Almodovar, S.; Gomez, J.L.; Flores, S.C.; Wilkes, D.S.; Tigno, X.T. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop summary: Enhancing opportunities for training and retention of a diverse biomedical workforce. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 562–567. [Google Scholar]

- Efstathiou, J.A.; Drumm, M.R.; Paly, J.P.; Lawton, D.M.; O’Neill, R.M.; Niemierko, A.; Leffert, L.R.; Loeffler, J.S.; Shih, H.A. Long-term impact of a faculty mentoring program in academic medicine. PLoS ONE 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino, M.M.; Zambrana, R.E. “How do you advance here? How do you survive?” An exploration of underrepresented minority (URM) faculty perceptions of mentoring modalities. Rev. High. Ed. 2019, 42, 457–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, T.M.; Braun, K.L.; Brandt, H.M.; Khan, S.; Tanjasiri, S.; Friedman, D.B.; Armstead, C.A.; Okuyemi, K.S.; Hebert, J.R. Mentoring and training of a cancer-related health disparities researchers committed to community-based participatory research. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2015, 9, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, M.D.; Arean, P.A.; Marshall, S.J.; Lovett, M.; O’Sullivan, P. Does mentoring matter: Results from a survey of faculty mentees at a large health sciences university. Med. Educ. Online 2010, 15, 5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, G.; Mendoza, F.S.; Fuentes-Afflick, E.; Mendoza, J.A.; Pachter, L.; Espinoza, J.; Fernandez, C.R.; Arnold, D.D.P.; Brown, N.M.; Gonzalez, K.M.; et al. Hot topics, urgent priorities, and ensuring success for racial/ethnic minority young investigators in academic pediatrics. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, G.; Mendoza, F.; Brimacombe, M.B.; Frazier, W. Program evaluation of the research in academic pediatrics initiative on diversity (RAPID): Impact on career development and professional society diversity. Acad. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, G.; Mendoza, F.S.; DeBaun, M.R.; Fuentes-Afflick, E.; Jones, V.F.; Mendoza, J.A.; Raphael, J.L.; Wang, C.J. Keys to academic success for under-represented minority young investigators: Recommendations from the Research in Academic Pediatrics Initiative on Diversity (RAPID) National Advisory Committee. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harawa, N.T.; Manson, S.M.; Mangione, C.M.; Penner, L.A.; Norris, K.C.; DeCarli, C.; Scarinci, I.C.; Zissimopoulos, J.; Buchwald, D.S.; Hinton, L.; et al. Strategies for enhancing research in aging health disparities by mentoring diverse investigators. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2017, 1, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, J.; Eide, K.; Harwood, E.; Ali, R.; Zhu, Z.; Cutler, J. Exploring professional development for new investigators underrepresented in the federally funded biomedical research workforce. Ethn. Dis. 2019, 29, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Louis, G.; Ayappa, I.; Rapoport, D.; Zizi, F.; Airhihenbuwa, C.; Okuyemi, K.; Ogedegbe, G. Mentoring junior URM scientists to engage in sleep health disparities research: Experience of the NYU PRIDE Institute. Sleep Med. 2016, 18, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, C.A.; Berman, J.R.; Robbins, L.; Paget, S.A. What mentors tell us about acknowledging effort and sustaining academic research mentoring: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Ed. Health Prof. 2019, 39, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, S. Early-stage investigators and institutional interface: Importance of organization in the mentoring culture of today’s universities. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, C.A.; Mutrie, A.; Ward, D.; Lewis, V. A sustainable course in research mentoring. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2014, 7, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masterson-Creber, R.M.; Baldwin, M.W.; Brown, P.J.; Rao, M.K.; Goyal, P.; Hummel, S.; Dodson, J.A.; Helmke, S.; Maurer, M.S. Facilitated peer mentorship to support aging research: A RE-AIM evaluation of the CoMPAdRE program. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milburn, N.G.; Hamilton, A.B.; Lopez, S.; Wyatt, G.E. Mentoring the next generation of behavioral health sciences to promote health equity. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2019, 89, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofili, E.O.; Fair, A.; Norris, K.; Verbalis, J.G.; Poland, R.; Bernard, G.; Stephens, D.S.; Dubinett, S.M.; Imperato-McGinley, J.; Dottin, R.P.; et al. Models of interinstitutional partnerships between research intensive universities and minority serving institutions (MSI) across the clinical translational science award (CTSA) consortium. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfund, C.; Byars-Winston, A.; Branchaw, J.; Hurtado, S.; Egan, K. Defining attributes and metrics of effective mentoring. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, S238–S248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, N. Developing and Optimizing Your Mentoring Relationships; NIH Regional Seminar: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2020.

- Shea, J.A.; Stern, D.T.; Klotman, P.E.; Clayton, C.P.; O’Hara, J.L.; Feldman, M.D.; Griendling, K.K.; Moss, M.; Straus, S.E.; Jagsi, R. Career development of physician scientists: A survey of leaders in academic medicine. Am. J. Med. 2011, 124, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiramizu, B.; Shambaugh, V.; Petrovich, H.; Seto, T.B.; Ho, T.; Mokuau, N.; Hedges, J.R. Leading by success: Impact of a clinical & translational research infrastructure program to address health inequities. J. Racial Ethn. Health Dispar. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder-Mackler, L. 46th Mary McMillian Lecture: Not Eureka. Phys. Ther. 2015, 95, 1446–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sorkness, C.A.; Pfund, C.; Ofili, E.O.; Kolawole, S.O.; Vishwanatha, J.K. A new approach to mentoring for research careers: The National Research Mentoring Network (NRMN). BMC Proc. 2017, 11 (Suppl. 12), 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, K.A.; Norton, W.E.; Stirman, S.W.; Melvin, C.; Brownson, R. Developing the next generation of dissemination and implementation researchers: Insights from initial trainees. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoff, D.M. Enhancing diversity and productivity of the HIV behavioral research workforce through research education mentoring programs. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 2889–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, M.Y.; Lanier, Y.A.; Willis, L.A.; Castellanos, T.; Dominguez, K.; Fitzpatrick, L.; Miller, K.S. Strengthening the network of mentored, underrepresented minority and leaders to reduce HIV-related health disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 2207–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, C.; Schwartz, L.S.; Toto, R.; Merchant, C.; Fair, A.S.; Gabrilove, J.L. Transition to independence: Characteristics and outcomes of mentored career development (KL2) scholars at clinical and translational science award institutions. Acad. Med. 2017, 92, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teruya, S.A.; Bazargan-Hejaxi, S.; Mojtahedzadeh, M.; Doshi, M.; Russell, K.; Parker-Kelly, D.; Friedman, T.C. A review of programs, components and outcomes in biomedical research faculty development. Int. J. Univ. Teach. Fac. Dev. 2013, 4, 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe, R.J.; Vishwanatha, J.K.; Harwood, E.M.; Krug, E.L.; Unold, T.; Boman, K.E.; Jones, H.P. The impact of grantsmanship self-efficacy on early state investigators of the National Research Mentoring Network Steps toward Academic Research (NRMN STAR). Ethn. Dis. 2020, 30, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkey, P.; Jatoi, A.; Williams, A.; Mayer, A.; Ko, M.; Files, J.; Blair, J.; Hayes, S. The positive impact of a facilitated peer mentoring program on academic skills of women faculty. BMC Med. Educ. 2012, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez, G.E.; Huaman, M.A.; Powell, K.R.; Cohn, S.E.; Swaminathan, S.; Outlaw, M.; Schulte, G.; McNeil, Q.; Currier, J.S.; Del Rio, C.; et al. Outcomes of a career development program for underrepresented minority investigators in the AIDS clinical trials group. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermund, S.H.; Hamilton, E.L.; Griffith, S.B.; Jennings, L.; Dyer, T.V.; Mayer, K.; Wheeler, D. Recruitment of underrepresented minority researchers into HIV prevention research: The HIV prevention trials network scholars program. Aids Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2018, 34, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanatha, J.K.; Jones, H.P. Implementation of the steps toward academic research (STAR) fellowship program to promote underrepresented minority faculty into health disparity research. Ethn. Dis. 2018, 28, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrana, R.E.; Ray, R.; Espino, M.M.; Castro, C.; Cohen, B.D.; Eliason, J. Don’t Leave Us Behind: The importance of mentoring for underrepresented minority faculty. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 52, 40–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.; White, D.E.; Benzies, K.; Rosenau, P. Exploring mentorship programs and components in nursing academia: A qualitative study. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2017, 7, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.H.; Baldi, B.; Sorcinelli, M.D. Mutual mentoring for early career and underrepresented faculty: Model, research, and practice. Innov. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, D.R.; Tolson, D. A mentoring guide for nursing faculty in higher education. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2014, 7, 727–732. [Google Scholar]

- Tourigny, L.; Pulich, M. A critical examination of formal and informal mentoring among nurses. Healt. Care Manag. 2005, 24, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggett, K.N.; Borges, J.J.; Blanco, M.A.; Wulf, K.; Hurtubise, L. A perfect match? A scoping review of the influence of personality matching on adult mentoring relationships—Implications for academic medicine. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2020, 40, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T.D.; Eby, L.T.; Lentz, E. Mentoring behaviors and mentorship quality associated with formal mentoring programs: Closing the gap between research and practice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.T.; Daly, B.P.; Leong, F.T. Mentoring in research: A developmental approach. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, N.M.; Lucas, L.; Hyers, L.L. Mentoring in higher education should be the norm to assure success: Lessons learned from the faculty mentoring program, West Chester University, 2008–2011. Mentor. Tutor. Partner. Learn. 2014, 22, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, P. The Stress of Being a Minority Faculty Member. Chronicle of Higher Education, 65. Available online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-stress-of-being-a-minority-faculty-member/ (accessed on 23 September 2020).

- Gumpertz, M.; Durodoye, R.; Griffin, E.; Wilson, A. Retention and promotion of women and underrepresented minority faculty in science and engineering at four large land grant institutions. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]