Abstract

In view of the increasing importance of sports to people and the impact of COVID-19 on people’s lives, home-based exercise has become a popular choice for people to keep fit due to its unique advantages and its popularity is expected to keep growing in the future. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the development direction of home-based exercise and put in the corresponding efforts. However, there is currently a lack of research on all aspects of home-based exercise. The purpose of this research was to investigate the effective sustainable development strategy of home-based exercise in China through a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) and AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process) hybrid model. Thirteen factors corresponding to the SWOT analysis were identified through a literature review and expert opinions. The results show that in China the advantages and potential outweigh the weaknesses and threats of home-based exercise. Home-based exercise should grasp the external development opportunities and choose the SO development strategic type that combines internal strengths and external opportunities. As the core for the development of home-based exercise, this strategy should be given priority. To sum up, home-based exercise is believed to have a bright future.

1. Introduction

At the end of 2019, the COVID-19 epidemic broke out and spread all over the world. During the prevention and control period of the pandemic, various sports venues were not open. This scenario where all sports venues are shut down is challenging to everyone who needs exercise. In January 2020, the General Administration of Sports of China issued the “Notice on Vigorously Promoting Scientific Home-based Exercise Methods”, requesting local sports departments to introduce simple, scientific, and effective home-based exercise methods based on local conditions. Since then, “home-based exercise” has gradually become a hot topic in China.

The idea of home-based exercise is to fully utilize the space in your home and make it act as a sports venue, with your own or family members, with your hands or using some portable equipment, to perform a series of applicable sports to strengthen your physical fitness and mentality. Home-based exercise is popular among people of all ages due to its convenience and is one of the important ways to stay healthy. People carry out various forms of sports at home, which not only strengthen their physical fitness and improve their own immunity, but also help relieve a series of psychological problems caused by COVID-19 [1,2,3,4].

Before the outbreak of the epidemic, home-based exercise was mainly used as aids for patient treatment or as means to restore physical function after surgery. Existing researches show that home-based exercise has good auxiliary effects on the treatment of fractures, osteoarthritis, and other musculoskeletal system diseases [5,6,7,8,9,10], cardio-cerebral vascular system diseases [11,12,13,14,15,16], respiratory system diseases [17,18,19], and even cancers [20,21,22,23]. Home-based exercise also has effects on supporting the treatment of nervous system diseases such as depression and Parkinson’s disease [24,25,26,27,28].

After the outbreak of the epidemic, in order to reduce people going out and avoid too much contact with each other to cause infection, home-based exercise replaced sports outdoors or in specific venues and became an inevitable choice to meet people’s needs. According to the study of Bo Pu et al. [29], during the epidemic, people mainly carried out the five aspects of home-based exercise, that is, gymnastics, walking or jogging, stretching exercises, housework, etc. It shows that male, married, and more than 25-year-old participants are more likely to do home-based exercise [29,30,31,32].

As COVID-19 still poses a huge threat to the public health, more and more people around the world have adopted home-based exercise. Home-based exercise has the prospect of becoming a common way for people to participate in physical activities. This study will employ a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) and AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process) hybrid model to provide a certain reference for the sustainable development of home-based exercise in China, and also it can provide some references for the development of home-based exercise in other countries.

1.1. SWOT Analysis

The SWOT analysis is a widely used tool for analyzing internal and external environments in order to attain a systematic approach and support for decision situations [33]. By applying the SWOT analysis in scientific research, people are able to draw a series of conclusions from the research objects including the main strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Most articles on the SWOT analysis only presented a literal description of the analysis and a few conducted quantified analysis and as planning processes are often complicated by numerous criteria and interdependencies, it may lead to the insufficient use of this analytical method [33,34,35].

1.2. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

The analytical hierarchy process (AHP) is a multiple criteria decision analysis (MCDA) method which helps in addressing the complicated decision problems [36,37]. The advantages of AHP include its ability to qualitatively and quantitatively analyze decision attributes, and its flexibility with regard to the setting of objectives [38]. It does so by structuring the problem, identifying decision making factors, measuring the importance of the factors, and synthesizing all the decision-making factors [39,40,41]. At present, AHP has been widely used in various areas, such as operations management [42], health care [43], project risk assessment [44], etc. [45,46]. However, AHP also has some defects, for example, it is criticized for its possible rank reversal phenomenon [47].

1.3. SWOT-AHP Model

Since the SWOT analysis includes no quantitative analysis, AHP can be integrated with the SWOT analysis [48,49,50]. Research by Mika Marttunen et al. shows that SWOT is most often used in combination with MCDA methods, and the mixed use of SWOT and AHP is the most common one [51]. Using AHP, each group of SWOT can be created as a pairwise comparison matrix, the weights and intensities of the SWOT groups and factors can be measured [50]. In this way, the reliability of the SWOT analysis can be improved. Many studies in different disciplines have already achieved good results by utilizing the SWOT-AHP hybrid model [38,48,52,53], and this method has also been applied in sports science and physical education [39,54,55,56].

2. Methods

2.1. Factors Generation

In order to determine the factors, the expert panel of sports science and medical science conducts a SWOT analysis. First, 10 expert panel members leading by Prof. Xingquan Chen from the Physical Education College of Sichuan University and West China Hospital of Sichuan University conducted the SWOT analysis. Every member of the panel was asked to identify various strengths and weaknesses, opportunities and threats related to the development of home-based exercise. Based on the SWOT analysis, the authors selected 13 factors. Then, these factors were grouped into each SWOT category and were given a brief description (Table 1).

Table 1.

Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats-analytical hierarchy process (SWOT-AHP) factors and description.

2.2. AHP Instrument

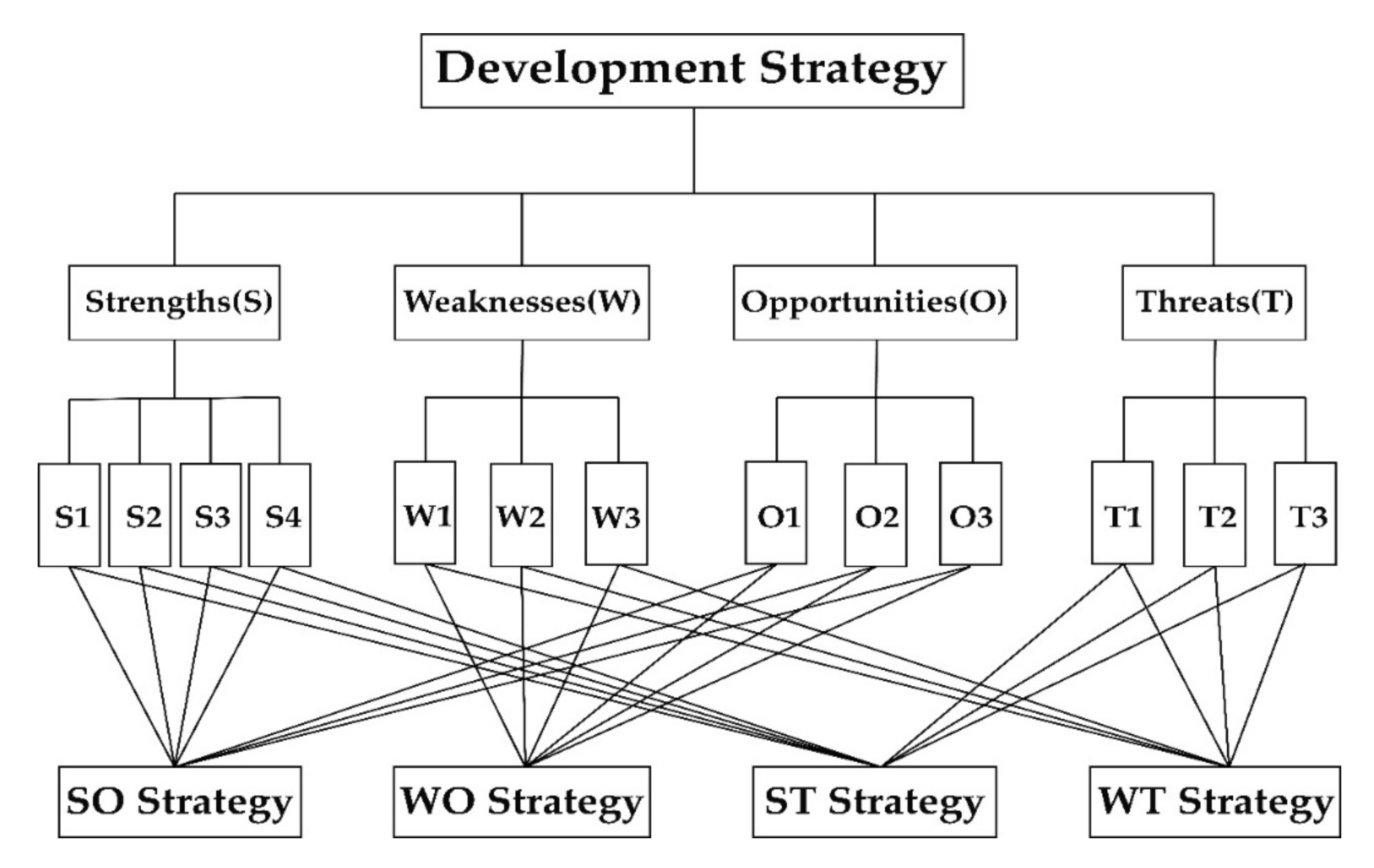

Based on the factors obtained by the SWOT analysis method, the AHP hierarchy was constructed (Figure 1). In order to carry out the analytic hierarchy process, a questionnaire was compiled that required a series of paired comparisons of factors. The respondents were asked to give answers by comparing two given factors according to his or her own preferences. They were asked to evaluate the factors based on the AHP scale (Table 2) [40].

Figure 1.

Hierarchical analysis structure graph.

Table 2.

The fundamental scale of absolute numbers.

2.3. Weight and Consistency Check

Since people tend to make inconsistent decisions, decision making science should judge the consistency of decision making, a consistency ratio (CR) test is a measurement of the validity of the survey respondents’ responses [39,40,41]. IBM SPSS Statistics 23 and MATLAB R2018b were used for statistics and calculations. The calculation methods and steps are as follows [40,53,54]:

- 1.

- Construct comparison matrix A.

- 2.

- Calculate the geometrical mean () of each row of the judgment matrix using the product square root method.

- 3.

- Normalize the geometrical mean of each row to get the eigenvectors ().

- 4.

- Calculate the maximum eigenvalue () of the judgment matrix.

- 5.

- Calculate the consistency index (CI) and the consistency ratio (CR).

When , CR represents the consistency of the matrix, RI values are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Average random consistency index.

If , the judgment matrix of the index meets the requirements of the consistency test.

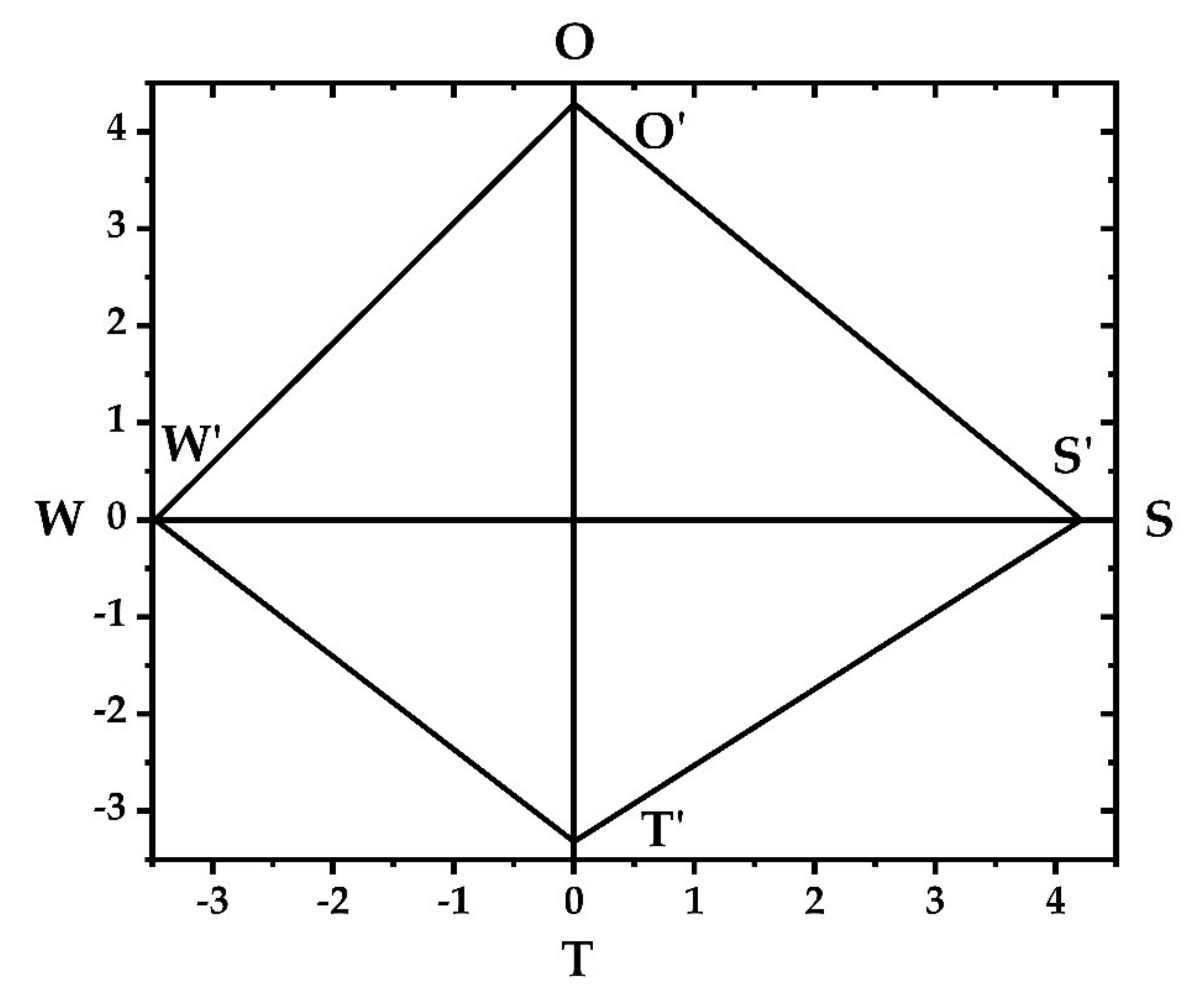

2.4. The Calculation of the Intensity of Factors and SWOT Strategic Quadrilateral

The magnitude of the factor’s effect is intensity, and its actual level is the estimated strength, then . The estimated strength of each factor is represented by 0–5 points, S, O are represented by positive values, W, T are represented by negative values, the greater the absolute value, the greater the intensity.

The four variables of S, W, O, and T total intensity are each semi-axis, forming a four semi-dimensional coordinate system. Draw the velocity values S’, W’, O’, and T’ on the corresponding semi-axes of the coordinate system to obtain a strategic quadrilateral.

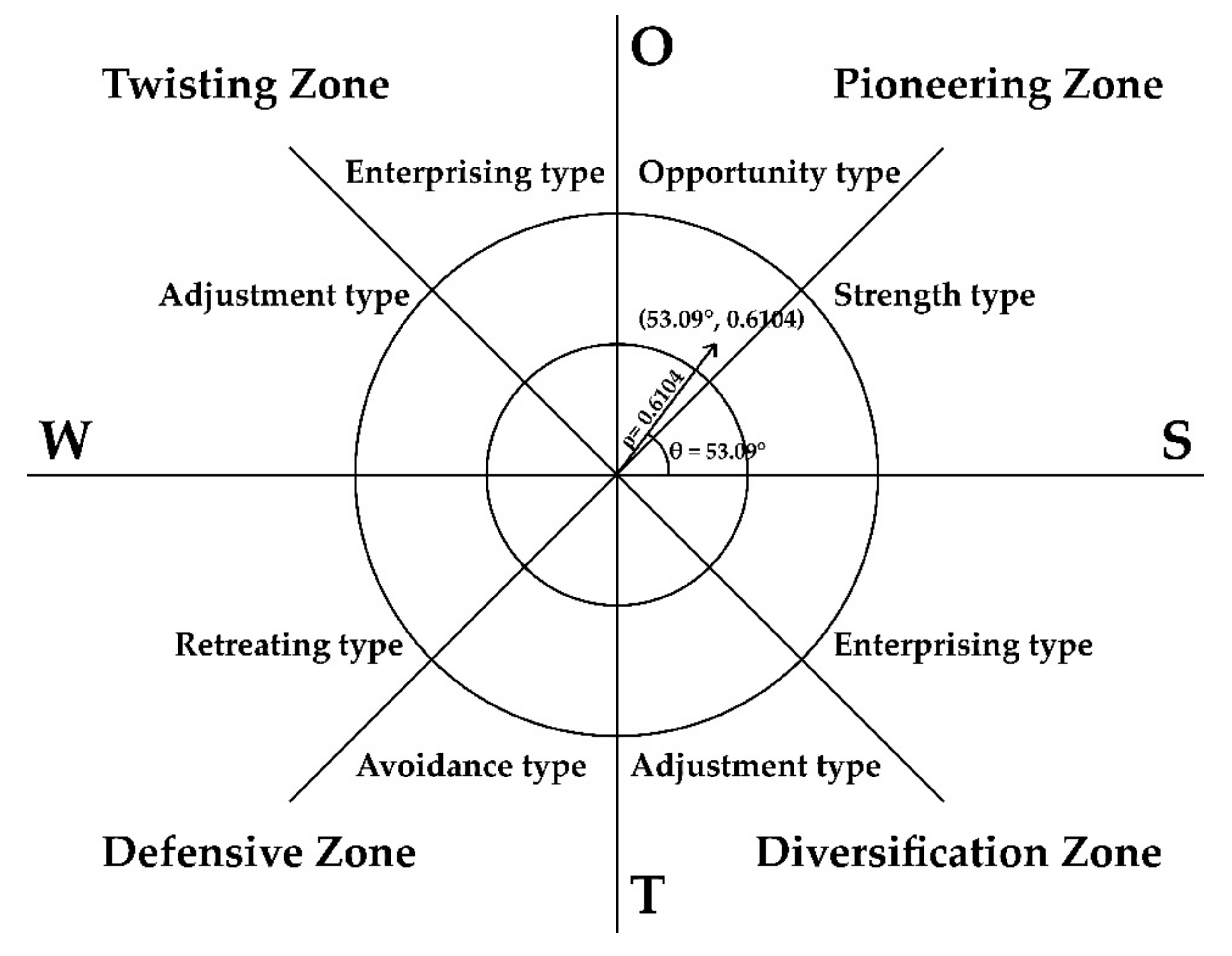

2.5. The Calculation of the Strategic Vector

In the SWOT-AHP model, the strategic azimuth angle is used to judge the strategic type, and the strategic intensity coefficient is used to judge the strategic intensity. In the polar coordinates of the strategic type and strategic intensity spectrum, the coordinates form a strategic vector with as the azimuth angle and as the polar diameter.

Calculate the strategic azimuth , the center of gravity coordinate is:

The strategic azimuth is:

Among them, and are the coordinates of S’, W’, O’, T’ in the strategic quadrilateral, respectively.

Calculate the strategic strength coefficient .

The strategic positive intensity is:

The strategic negative intensity is:

The strategic intensity coefficient is defined as:

The value range of is , and the size of indicates the intensity of the strategic type.

3. Results

3.1. AHP Weights and the Intensities of Factors

The results obtained in Table 4 and Table 5 show that opportunities are the most important consideration, followed by strengths, weaknesses, and threats. Under the strength category, construction of a leading sports nation was rated as the most important factor, followed by an increased awareness of exercise, time freedom, low cost, and convenience. Under weakness, less theoretical research and insufficient professional talents were rated as the most important factors, followed by limited space leads to fewer sports methods and monotonous and boring form of exercise. Under opportunity, the rapid development of intelligent sports was rated as the most important factor, followed by support provided by the government and the stable development of the sports industry. Under threat, fading enthusiasm for home-based exercise after the epidemic was rated as the most important factor, followed by easy to slack at home and noise.

Table 4.

Comparison matrix and weights of SWOT groups and factors.

Table 5.

The intensities of groups and factors.

3.2. SWOT Strategic Quadrilateral

The strategic quadrilateral (Figure 2) was drawn based on the calculation results of the total intensities of each group. The results are shown in Table 5:

Figure 2.

SWOT strategic quadrilateral.

3.3. Strategic Vector

- The center of gravity coordinate is:.

- The strategic azimuth is: .

- The strategic positive intensity is:

- The strategic negative intensity is:

- The strategic strength coefficient is:

It can be seen from Figure 3 that the coordinates are , indicating that the development of home-based exercise has a greater opportunity and its inherent advantages are also obvious.

Figure 3.

Strategic type and strategic intensity diagrams.

4. Discussion

The results of this study show that opportunities and strengths are more important than weaknesses and threats. It is concluded that home-based exercise in China should adopt the type of SO development strategy that combines internal advantages and external opportunities. When developing the home-based exercise with its featured advantages, its shortcomings should also be improved at the same time. The implementation focus of the development strategy of home-based exercise in China are as follows.

First, in the strength group, the construction of a leading sports nation is the highest rated factor, and under opportunity, support provided by the government has a high importance. With the support of various policies [57,58,59] and the stable development of China’s sports industry [67,68], the environment of sports in China will get better and better. It is necessary to seize this hard-won opportunity to improve the development of home-based exercise. Home-based exercise should be further promoted to the public with its unique strengths and it will become more popular in the future.

Second, in the opportunity group, the rapid development of intelligent sports is the highest rated factor. With the development of economy and technology in recent years, intelligent sports facilities are also constantly updated [62,63,64,65,66,69,70,71]. During the COVID-19 epidemic, various intelligent sports facilities also effectively encouraged people’s physical activities [72]. In the future, the home will become an important scene for the use of sports equipment. Home-based exercise will advance the development of intelligent sports, and the rapid development of intelligent sports can also propagate the home-based exercise development.

Third, in the weakness group, less theoretical research and insufficient professional talents have a relatively high importance. Home-based exercise hardly attracted attention in the past and few people have conducted targeted research on it. It is still used as a means of rehabilitation after illness or after surgery, rather than as general exercise methods for comprehensive analysis and research [73]. However, during the epidemic, more and more people realized the necessity of home-base exercise and used it as a daily approach to keep healthy and improve mental well-being [74]. Therefore, scholars and researchers should be encouraged to actively carry out empirical research on the home-based exercise, enrich and improve the theoretical system, and fill in academic gaps.

Fourth, under threat, fading enthusiasm for home-based exercise after the epidemic was the highest rated factor. The rapid rise of home-based exercise is mainly due to the epidemic which prevents people from participating in outdoor sports [2,72,74,75]. However, at present, the epidemic prevention and control situation in China is promising, and sports venues are gradually opening up, resulting in a decrease in the number of home-based exercisers. If home-based exercise and outdoor sports are combined and developed in coordination, a new pattern of sports for all will form.

Finally, the lower rated factors in weakness and threat groups also cannot be ignored. As mobile sports apps become more practical, the number of people studying online sports courses is also increasing [76,77,78]. Traditional online sports courses are mainly based on physical exercise such as muscle strength and flexibility training, which is pretty boring for people. Changes in the form of courses can be made in order to increase the joy of taking courses, which can increase people’s enthusiasm for participating in home-based exercise.

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 epidemic has a great impact on all walks of life, but for home-based exercise, it is a golden opportunity for development. This article uses the SWOT-AHP hybrid model to conduct empirical research on the development of home-based exercise in China. The results indicate that strengths and opportunities have a greater influence on the development of home-based exercise than weaknesses and threats in the four dimensions of SWOT analysis. With the support of the various policies issued by governments and the rapid development of intelligent sports, home-based exercise should grasp the external development opportunities and choose the SO development strategic type that combines internal advantages and external opportunities. However, home-based exercise still has disadvantages such as limited space, low interest, and potential disturbance to the people. However, these problems can be solved with the development of science and technology. Home-based exercise will eventually form a culture and be thoroughly integrated into the lives of people.

The limitation of this study is the limited number of experts participating in the SWOT analysis and the limited SWOT factors, and the conclusions obtained may have deviations within an acceptable range. Future research will involve more experts in different fields for further analysis. The opinions of experts in different fields can be compared. The SWOT factors will be expanded, and the SWOT analysis can be combined with different MCDA methods for a comparative analysis to obtain more reliable data. Due to the bright future of intelligent sports facilities, research on their application in different sports will also be conducted in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and X.C.; methodology, H.L.; software, H.L.; validation, H.L. and X.C.; formal analysis, H.L.; investigation, H.L. and X.C.; resources, H.L. and X.C.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.; writing—review and editing, X.C. and Y.F.; visualization, X.C.; supervision, X.C.; project administration, X.C.; funding acquisition, X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by “The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, X.; Xue, Q.; Zhu, K.; Wan, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Song, R. The prevalence of behavioral problems among school-aged children in home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic in china. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, J.P.; Hevel, D.J.; Reifsteck, E.J.; Drollette, E.S. Physical activity is positively associated with college students’ positive affect regardless of stressful life events during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 52, 101826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatori, S.; Donati Zeppa, S.; Preti, A.; Gervasi, M.; Gobbi, E.; Ferrini, F.; Rocchi, M.B.L.; Baldari, C.; Perroni, F.; Piccoli, G.; et al. Dietary Habits and Psychological States during COVID-19 Home Isolation in Italian College Students: The Role of Physical Exercise. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.M.; Landry, M.J.; Gustat, J.; Lemon, S.C.; Webster, C.A. Physical distancing physical inactivity. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunay, V.B. Hospital-based versus home-based proprioceptive and strengthening exercise programs in knee osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 2010, 44, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Hu, N.; Tan, J.H. Efficacy of home-based exercise programme on physical function after hip fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int. Wound J. 2019, 17, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büker, N.; Şavkın, R.; Ök, N. Comparison of Supervised Exercise and Home Exercise after Ankle Fracture. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2019, 58, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, B.W.; Cornelius, A.E.; Van Raalte, J.L.; Tennen, H.; Armeli, S. Predictors of adherence to home rehabilitation exercises following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Rehabil. Psychol. 2013, 58, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ay, S.; Evcik, D.; Kutsal, Y.G.; Toraman, F.; Okumuş, M.; Eyigör, S.; Şahin, N. Compliance to home-based exercise therapy in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 62, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, S.; Alghadir, A.; Brismée, J.-M. Effect of Home Exercise Program in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. J. Geriatric Physical Therapy 2016, 39, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, M.M.; Polonsky, T.S. Home-Based Exercise A Therapeutic Option for Peripheral Artery Disease. Circulation 2016, 134, 1127–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohkubo, T.; Hozawa, A.; Nagatomi, R.; Fujita, K.; Sauvaget, C.; Watanabe, Y.; Anzai, Y.; Tamagawa, A.; Tsuji, I.; Imai, Y.; et al. Effects of exercise training on home blood pressure values in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. J. Hypertens. 2001, 19, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, R.; Marwick, T. Efficacy of home-based exercise programmes for people with chronic heart failure: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2009, 16, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.-K.; Lin, Y.-W.; Chen, C.-L.; Tsai, S.-W. Cardiac Rehabilitation vs. Home Exercise After Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2006, 85, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, V.; Paul, N. Sudden deaths following the unexpected demise of a popular politician in India. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010, 145, 266–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besnier, F.; Gayda, M.; Nigam, A.; Juneau, M.; Bherer, L. Cardiac Rehabilitation During Quarantine in COVID-19 Pandemic: Challenges for Center-Based Programs. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1835–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, P.; Li, J.; Xiao, L.; Li, N.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Su, J.; Wang, Z.; Shan, C.; et al. Home-Based Prescribed Pulmonary Exercise in Patients with Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Vis. Exp. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnke, M.; Taube, C.; Kirsten, D.; Lehnigk, B.; JÖRres, R.A.; Magnussen, H. Home-based exercise is capable of preserving hospital-based improvements in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir. Med. 2000, 94, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytekin, E.; Caglar, N.S.; Ozgonenel, L.; Tutun, S.; Demiryontar, D.Y.; Demir, S.E. Home-based exercise therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: Effects on pain, mobility, disease activity, quality of life, and respiratory functions. Clin. Rheumatol. 2011, 31, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonders, K.Y.; Whisler, G.; Loy, H.; Holt, B.; Bohachek, K.; Wise, R. Ten weeks of home-based exercise attenuates symptoms of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in breast cancer patients. Health Psychol. Res. 2013, 1, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiechle, M.; Friese, K.; Felberbaum, R. Bewegungsmangel, ungesunde Ernährung und Übergewicht. Der Gynäkologe 2019, 52, 480–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.; Jones, J.; Alibhai, S.M.H.; Santa Mina, D. What Is the “Home” in Home-Based Exercise? The Need to Define Independent Exercise for Survivors of Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 926–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, D.H.; Kang, D.W.; Min, J.H.; Lee, J.W.; Chu, S.H.; Cho, M.S.; Kim, N.K.; Jeon, J.Y. Effects of a 12-week home-based exercise program on quality of life, psychological health, and the level of physical activity in colorectal cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Supportive Care Cancer 2018, 27, 2933–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuch, F.B.; Vancampfort, D.; Richards, J.; Rosenbaum, S.; Ward, P.B.; Stubbs, B. Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 77, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, X.; Tian, X.; Zhang, H.; Huang, R.; Li, N.; Chen, P.; Wang, R. Exercise as a prescription for patients with various diseases. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 422–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, S.B.; Øverland, S.; Hatch, S.L.; Wessely, S.; Mykletun, A.; Hotopf, M. Exercise and the Prevention of Depression: Results of the HUNT Cohort Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanton, R.; Reaburn, P. Exercise and the treatment of depression: A review of the exercise program variables. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2014, 17, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, A.; Allen, N.E.; Dennis, S.; Canning, C.G.; Preston, E. Home-based prescribed exercise improves balance-related activities in people with Parkinson’s disease and has benefits similar to centre-based exercise: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2019, 65, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, B.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Z.; Qiu, Y. The Relationship between Health Consciousness and Home-Based Exercise in China during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.Y.; Hsu, H.C.; Lee, S.D. Gender differences in related influential factors of regular exercise behavior among people in Taiwan in 2007: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molanorouzi, K.; Khoo, S.; Morris, T. Motives for adult participation in physical activity: Type of activity, age, and gender. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennie, J.A.; De Cocker, K.; Smith, J.J.; Wiesner, G.H. The epidemiology of muscle-strengthening exercise in Europe: A 28-country comparison including 280,605 adults. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazinoory, S.; Abdi, M.; Azadegan-Mehr, M. Swot Methodology: A State-of-the-Art Review for the Past, a Framework for the Future/Ssgg Metodologija: Praeities Ir Ateities AnalizĖ. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2011, 12, 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, M.M.; Nixon, J. Exploring SWOT analysis—Where are we now? J. Strategy Manag. 2010, 3, 215–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-H.; Huang, W.-C. Application of a quantification SWOT analytical method. Math. Comput. Model. 2006, 43, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sałabun, W.; Wątróbski, J.; Shekhovtsov, A. Are MCDA Methods Benchmarkable? A Comparative Study of TOPSIS, VIKOR, COPRAS, and PROMETHEE II Methods. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyoud, S.H.; Fuchs-Hanusch, D. A bibliometric-based survey on AHP and TOPSIS techniques. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 78, 158–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Park, J. A Sustainable Development Strategy for the Uzbekistan Textile Industry: The Results of a SWOT-AHP Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Walsh, P. SWOT and AHP hybrid model for sport marketing outsourcing using a case of intercollegiate sport. Sport Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, N.; Ramanathan, R. A review of applications of Analytic Hierarchy Process in operations management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 138, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberatore, M.J.; Nydick, R.L. The analytic hierarchy process in medical and health care decision making: A literature review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2008, 189, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.A.; Albahar, J.F. Project risk assessment using the analytic hierarchy process. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1991, 38, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, O.S.; Kumar, S. Analytic hierarchy process: An overview of applications. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 169, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, A.; Labib, A. Review of the main developments in the analytic hierarchy process. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sałabun, W.; Ziemba, P.; Wątróbski, J. The Rank Reversals Paradox in Management Decisions: The Comparison of the AHP and COMET Methods. In Intelligent Decision Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 2016, pp. 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Yan, H. An Improvement Research of SWOT Method Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 263–266, 2287–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Mohamed, M.; Smarandache, F. An Extension of Neutrosophic AHP–SWOT Analysis for Strategic Planning and Decision-Making. Symmetry 2018, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W. Integrated analytic hierarchy process and its applications—A literature review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2008, 186, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marttunen, M.; Lienert, J.; Belton, V. Structuring problems for Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis in practice: A literature review of method combinations. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 263, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Xie, H.; Yang, D.; Xiahou, X.; Skibniewski, M.J.; Huang, W. Strategy formulation for the sustainable development of smart cities: A case study of Nanjing, China. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2020, 24, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, Y.; Qian, Z. Hybrid SWOT-AHP Analysis of Strategic Decisions of Coastal Tourism: A Case Study of Shandong Peninsula Blue Economic Zone. J. Coast. Res. 2019, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.H.; Wang, M.J.; Han, Y.G. The Development Strategy of China’s Wushu Sanda Based on SWOT-AHP Model. China Sport Sci. Technol. 2016, 52, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Liang, Z. Evaluation of Henan Sports Tourism Resources Based on AHP and Fuzzy Mathematics. Areal Res. Dev. 2012, 31, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Environment Analysis Strategy for Revitalizing Cultural Sports. J. Korea Entertain. Ind. Assoc. 2018, 12, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee, C.C.; Council, S. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued the “Outline of the ‘Healthy China 2030’ Plan”. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Office of the State Council. Notice of the General Office of the State Council on Issuing the Outline for Building a Leading Sports Nation. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-09/02/content_5426485.htm (accessed on 2 September 2019).

- General Office of the State Sports General Administration. Notice of the General Office of the State Sports General Administration on Vigorously Promoting Scientific Home-based Exercise Methods. Available online: http://www.sport.gov.cn/n316/n336/c941798/content.html (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Research i. 2014–2021 China’s Online Sports Goods Market Scale and Forecast. Available online: https://data.iimedia.cn/data-classification/detail/13209702.html (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Research i. 2012–2022 China’s Sports Industry Output Value and Forecast. Available online: https://data.iimedia.cn/data-classification/detail/13002939.html (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- Ma, H.; Pang, X. Research and Analysis of Sport Medical Data Processing Algorithms Based on Deep Learning and Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 118839–118849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, N.; Yu, W.; Han, X. Wearable heart rate monitoring intelligent sports bracelet based on Internet of things. Measurement 2020, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S. Sports Equipment Based on High-Tech Materials. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 340, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.-H.; Kai, H.; Luo, X.-J. Application of Computer Virtual Reality Technology in Modern Sports. In Proceedings of the 2013 Third International Conference on Intelligent System Design and Engineering Applications, Hong Kong, China, 16–18 January 2013; pp. 362–364. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.-Y.; Zhou, Y. Study on the Application of VR Technology in Sport Reality Shows. In Proceedings of the 2018 1st International Cognitive Cities Conference (IC3), Okinawa, Japan, 7–9 August 2018; pp. 200–201. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.-L.; Zhang, H.-J.; Guo, X.-T. Research on the future development prospects of sports products industry under the mode of e-commerce and internet of things. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2020, 18, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, L.; Guan, X.; Ye, S. Quantitative Evaluation and Prediction Analysis of the Healthy and Sustainable Development of China’s Sports Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W. Application of Plastic Composites in Sports Facilities and Fitness Equipment. China Plast. Ind. 2019, 47, 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte-Rojo, A.; Bloomer, P.M.; Rogers, R.J.; Hassan, M.A.; Dunn, M.A.; Tevar, A.D.; Vivis, S.L.; Bataller, R.; Hughes, C.B.; Ferrando, A.A.; et al. Introducing EL-FIT (Exercise and Liver FITness): A Smartphone App to Prehabilitate and Monitor Liver Transplant Candidates. Liver Transplant. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConville, R.; Archer, G.; Craddock, I.; Kozlowski, M.; Piechocki, R.; Pope, J.; Santos-Rodriguez, R. Vesta: A digital health analytics platform for a smart home in a box. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 114, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearnbach, S.N.; Flanagan, E.W.; Hochsmann, C.; Beyl, R.A.; Altazan, A.D.; Martin, C.K.; Redman, L.M. Factors Protecting against a Decline in Physical Activity during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loellgen, H.; Zupet, P.; Bachl, N.; Debruyne, A. Physical Activity, Exercise Prescription for Health and Home-Based Rehabilitation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyat, J.H.; Ahmad, H.; Avina-Galindo, A.M.; Kazanjian, A.; Gupta, A.; Ellis, U.; Ashe, M.C.; Vila-Rodriguez, F.; Halli, P.; Salmon, A.; et al. A rapid review of home-based activities that can promote mental wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippi, G.; Henry, B.M.; Bovo, C.; Sanchis-Gomar, F. Health risks and potential remedies during prolonged lockdowns for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Diagnosis 2020, 7, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Fernandez, J.; Galvez-Ruiz, P.; Grimaldi-Puyana, M.; Angosto, S.; Fernandez-Gavira, J.; Bohorquez, M.R. The Promotion of Physical Activity from Digital Services: Influence of E-Lifestyles on Intention to Use Fitness Apps. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitrian, P.; Buil, I.; Catalan, S. Gamification in sport apps: The determinants of users’ motivation. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2020, 29, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Ramirez, L.; Notario, R.O.; Avalos-Ramos, M.A. The Relevance of Mobile Applications in the Learning of Physical Education. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).