Parents ASSIST: Acceptability and Feasibility of a Video-Based Educational Series for Sexuality-Inclusive Communication between Parents and Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Sons

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Intervention Description

2.2. Intervention Development Procedures

2.3. Participant Recruitment

2.4. Study Procedures and Measures

3. Findings

3.1. Demographic Findings

3.2. Feasibility

3.3. Acceptability

3.4. Overall Impressions of Parents ASSIST

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and Youth. April 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/index.html (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018 (Updated). 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-31.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey: Data Summary & Trend Reports 2009–2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/YRBSDataSummaryTrendsReport2019-508.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Agnew-Brune, C.B.; Balaji, A.B.; Mustanski, B.; Newcomb, M.E.; Prachand, N.; Braunstein, S.L.; Brady, K.A.; Hoots, B.E.; Smith, J.S.; Paz-Bailey, G.; et al. Mental health, social support, and HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among HIV-negative adolescent sexual minority males: Three U.S. cities, 2015. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 3419–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivey-Stephenson, A.Z.; Demissie, Z.; Crosby, A.E.; Stone, D.M.; Gaylor, E.; Wilkins, N.; Lowry, R.; Brown, M. Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Suppl. 2020, 69, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.M. LGBT Identification Rises to 5.6% in Latest U.S. Estimate. Gallup. 21 February 2021. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Twenge, J.M.; Sherman, R.A.; Wells, B.E. Changes in American adults’ reported same-sex sexual experiences and attitudes, 1973–2014. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016, 45, 1713–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grov, C.; Rendina, H.J.; Parsons, J.T. Birth cohort differences in sexual identity development milestones among HIV-negative gay and bisexual men in the United States. J. Sex Res. 2018, 55, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, E.A.; Fontenot, H.B. Parent-adolescent sex communication with sexual and gender minority youth: An integrated review. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2020, 34, e37–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills-Koonce, W.R.; Rehder, P.D.; McCurdy, A.L. The significance of parenting and parent-child relationships for sexual and gender minority adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2018, 28, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newcomb, M.E.; LaSala, M.C.; Bouris, A.; Mustanski, B.; Prado, G.; Schrager, S.M.; Huebner, D.M. The unfluence of families on LGBTQ youth health: A call to action for innovation in research and intervention development. LGBT Health 2019, 6, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, D.D.; Docherty, S.L.; Relf, M.V.; McKinney, R.E.; Barroso, J.V. “It’s Almost Like Gay Sex Doesn’t Exist”: Parent-Child Sex Communication According to Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Male Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Res. 2019, 34, 528–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, D.D.; Abboud, S.; Barroso, J. Hegemonic Masculinity during Parent-Child Sex Communication with Sexual Minority Male Adolescents. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2019, 14, 417–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herek, G. A Nuanced View of Stigma for Understanding and Addressing Sexual and Gender Minority Health Disparities. LGBT Health 2016, 3, 397–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaSala, M.C. Condoms and connection: Parents, gay and bisexual youth, and HIV risk. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 2015, 41, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coakley, T.M.; Randolph, S.; Shears, J.; Beamon, E.R.; Collins, P.; Sides, T. Parent-youth communication to reduce at-risk sexual behavior: A systematic literature review. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2017, 27, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, W.; Brown, L.K.; Lescano, C.M.; Kell, H.; Spalding, K.; Diclemente, R.; Donenberg, G. Parent-adolescent sexual communication: Associations of condom use with condom discussions. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, K.S.; Moreau, C.; Trussell, J. Associations between sexual and reproductive health communication and health service use among U.S. adolescent women. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2012, 44, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, M.K.; Cederbaum, J.A. Talking to daddy’s little girl about sex: Daughters’ reports of sexual communication and support from fathers. J. Fam. Issues 2011, 32, 550–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapungu, C.T.; Baptiste, D.; Holbeck, G.; McBride, C.; Robinson-Brown, M.; Sturdivant, A.; Crown, L.; Paikoff, R. Beyond the “birds and the bees”: Gender differences in sex-related communication among urban African-American adolescents. Fam. Process 2010, 49, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widman, L.; Choukas-Bradley, S.; Noar, S.M.; Nesi, J.; Garrett, K. Parent-adolescent sexual communication and adolescent safer sex behavior: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campero, L.; Walker, D.; Atienzo, E.E.; Gutierrez, J.P. A quasi-experimental evaluation of parents as sexual health educators resulting in delayed sexual initiation and increased access to condoms. J. Adolesc. 2011, 34, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovar, C.L.; Salsberry, P.J. Does a satisfactory relationship with her mother influence when a 16-year-old begins to have sex? MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2012, 37, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, D.D.; Barroso, J. 21st Century Parent-Child Sex Communication in the U.S.: A Process Review. Annu. J. Sex Res. 2017, 54, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, I.D.; Friedman, D.B. We need health information too: A systematic review of studies examining the health information seeking and communication practices of sexual minority youth. Health Educ. J. 2012, 72, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouris, A.; Guilamo-Ramos, V.; Pickard, A.; Shiu, C.; Loosier, P.S.; Dittus, P.; Gloppen, K.; Waldmiller, J.M. A systematic review of parental influences on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Time for a new public health research and practice agenda. J. Prim. Prev. 2010, 31, 273–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bregman, H.R.; Malik, N.M.; Page, M.J.; Makynen, E.; Lindahl, K.M. Identity profiles in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: The role of family influences. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Huebner, D.; Diaz, R.M.; Sanchez, J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, C.; Russell, S.T.; Huebner, D.; Diaz, R.; Sanchez, J. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2010, 23, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.; Balaji, A.B.; Trujillo, L.; Rasberry, C.N.; Mustanski, B.; Newcomb, M.E.; Brady, K.A.; Prachand, N.G. Family factors and HIV-related risk behaviors among adolescent sexual minority males in three United States cities, 2015. LGBT Health 2020, 7, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, I.D.; Friedman, D.B.; Annang, L.; Spencer, S.M.; Lindley, L.L. Health communication practices among parents and sexual minority youth. J. LGBT Youth 2014, 11, 316–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaSala, M.C. Parental influence, gay youths, and safer sex. Health Soc. Work 2007, 32, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, M.E.; Feinstein, B.A.; Matson, M.; Macapagal, K.; Mustanski, B. “I have no idea what’s going on out there”: Parents’ perspectives on promoting sexual health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2018, 15, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estes, M.L. ‘If there’s one benefit, you’re not going to get pregnant’: The sexual miseducation of gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals. Sex Roles 2017, 77, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, B.A.; Thomann, M.; Coventry, R.; Macapagal, K.; Mustanski, B.; Newcomb, M.E. Gay and bisexual adolescent boys’ perspectives on parent-adolescent relationships and parenting practices related to teen sex and dating. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2018, 47, 1825–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoma, B.C.; Huebner, D.M. Parental monitoring, parent-adolescent communication about sex, and sexual risk among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014, 18, 1604–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hutchinson, M.K.; Jemmott, J.B., III; Jemmott, L.S.; Braverman, P.; Fong, G.T. The role of mother–daughter sexual risk communication in reducing sexual risk behaviors among urban adolescent females: A prospective study. J. Adolesc. Health 2003, 33, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Kuhl, J., Beckman, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kreuter, M.W.; Wray, R.J. Tailored and targeted health communication: Strategies for enhancing information relevance. Am. J. Health Behav. 2003, 27, S227–S232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnall, R.; Travers, J.; Rojas, M.; Carballo-Diéguez, A. eHealth interventions for HIV prevention in high-risk men who have sex with men: A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Sheer, V.C.; Li, R. Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: A meta-analysis. J. Advert. 2015, 44, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, D.D.; Rosario, A.; Bond, K.; Villarruel, A.; Bauermeister, J. Parents ASSIST (Advancing Supportive and Sexuality-Inclusive Sex Talks): Iterative Development of a Sex Communication Video Series for Parents of Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Male Adolescents. J. Fam. Nurs. 2020, 26, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronowitz, T.; Todd, E.; Agbeshie, E.; Rennells, R.E. Attitudes that affect the ability of African American preadolescent girls and their mothers to talk openly about sex. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2007, 28, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschke, L.L.; Dettmer, K. ‘Don’t cross a man’s feet’: Hmong parent-daughter communication about sexual health. Sex Educ. 2012, 12, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, D.D.; Meanley, S.; Bond, K.; Agenor, M.; Relf, M.; Barroso, J. Topic Recollections and Recommendations for Inclusive Parent-Child Sex Communication by Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Adolescent Males. Behav. Med. 2021, 47, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dimension | Survey Question |

|---|---|

| Relatability | Q1. Could you relate to the characters? Q2. How interesting were the videos you watched? Q3. Would you describe their situations as realistic? |

| Likeability | Q4. Did you like what the main characters were saying? Q5. Do you think other parents might like to see the videos? Q6. How much did you like the video series you just watched? |

| Utility | Q7. Do you think that watching the videos could help increase parents’ knowledge about their sons’ health and sexuality questions? Q8. Do you think the videos you watched could make it more likely that other parents will seek further information about LGBTQ health and sexuality? Q9. Did the videos add to your learning about LGBTQ health and sexuality issues? Q10. How much new information did you learn as a result of the videos you just watched? |

| Recommendability | Q11. Would you recommend the animated videos to other parents of gay, bisexual, or queer adolescent males? Q12. Would you recommend watching these videos with your soon? Q13. Would you share the videos with your friends? |

| Realistic Quality | Q14. Were the stories realistic? Q15. Would you describe their situations as realistic? |

| Potential to Impact Communication | Q16. Do you think that watching the videos could help parents initiate and sustain sex and health discussions with their gay, bisexual, or queer sons? Q17. Do you think the videos you watched could make it more likely that other parents will want to initiate and sustain inclusive parent–child conversations about health and sexuality? Q18. Do you think that after watching the videos, parents will be more likely to initiative inclusive conversations about health and sexuality with their sons? Q19. Do you think that after watching the videos, parents will be more likely to sustain inclusive conversations about health and sexuality with their sons? Q20. Do you think the videos could help parents learn how to handle conversations about health and sexuality with adolescent sons and broach issues/questions centered on same-sex attractions or behaviors? |

| Frequency (n = 54) | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Parent’s Age | ||

| 32–40 | 11 | 20.6 |

| 41–50 | 35 | 65 |

| 53–60 | 6 | 11.3 |

| Not specified | 2 | 3.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 24 | 44.4 |

| Female | 30 | 55.6 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian/White | 44 | 81.5 |

| African American | 5 | 9.3 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 1.9 |

| Native American/Alaskan | 1 | 1.9 |

| Biracial | 3 | 5.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 7 | 13 |

| Non-Hispanic/Non-Latino | 47 | 87 |

| U.S. Region | ||

| Northeast | 16 | 29.8 |

| South | 13 | 24.3 |

| Midwest | 9 | 16.8 |

| West | 16 | 29.7 |

| Son’s Age | ||

| 14–16 | 26 | 48.1 |

| 17–19 | 17 | 31.5 |

| 20–24 | 11 | 20.5 |

| Son’s Grade | ||

| 8th grade | 8 | 14.8 |

| 9th grade | 8 | 14.8 |

| 10th grade | 6 | 11.1 |

| 11th grade | 7 | 13 |

| 12th grade | 9 | 16.7 |

| College/vocational/trade school | 11 | 20.4 |

| Finished college/vocational/trade school | 3 | 5.6 |

| Son’s Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay | 48 | 88.9 |

| Bisexual | 5 | 9.3 |

| Queer | 1 | 1.9 |

| Son’s Gender | ||

| Cisgender male | 54 | 100 |

| Time Known Son is GBQ | ||

| 1–2 months | 3 | 5.6 |

| 2–6 months | 5 | 9.3 |

| 6–12 months | 10 | 18.5 |

| 1–2 years | 16 | 29.6 |

| 2–4 years | 10 | 18.5 |

| More than 4 years | 10 | 18.5 |

| Domains * | Responses N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relatability | |||||

| Q1. | I definitely related to most or all the characters | I could relate to many of the characters | I could relate to some of the characters | I don’t know if I could relate to any of the characters | No, I could not relate to any of the characters |

| 15 (27.8) | 24 (44.4) | 14 (25.9) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Q2. | Extremely interesting | Very interesting | Moderately interesting | Slightly interesting | Not at all interesting |

| 11 (20.4) | 33 (61.1) | 8 (14.8) | 2 (3.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Q3. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 41 (75.9) | 13 (24.1) | 0 (0) | |||

| Likeability | |||||

| Q4. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 41 (75.9) | 13 (24.1) | 0 (0) | |||

| Q5. | Most or all would | Many would | I don’t know | A few would | None would |

| 15 (27.8) | 33 (61.1) | 4 (7.4) | 2 (3.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Q6. | Very much | Somewhat | Neutral | Not much | Not at all |

| 28 (51.9) | 22 (40.7) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (5.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Utility | |||||

| Q7. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 47 (87) | 7 (13) | 0 (0) | |||

| Q8. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 37 (68.5) | 17 (31.5) | 0 (0) | |||

| Q9. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 36 (66.7) | 14 (25.9) | 4 (7.4) | |||

| Q10. | A great deal | Some | Little | None | |

| 32 (59.3) | 19 (35.2) | 2 (3.7) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| Recommendability | |||||

| Q11. | Yes | No | |||

| 49 (90.7) | 5 (9.3) | ||||

| Q12. | Yes | No | |||

| 46 (85.2) | 8 (14.8) | ||||

| Q13. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 43 (73.6) | 10 (18.5) | 1 (1.9) | |||

| Realistic Quality | |||||

| Q14. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 35 (64.8) | 19 (35.2) | 0 (0) | |||

| Q15. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 41 (75.9) | 13 (24.1) | 0 (0) | |||

| Potential to Impact Communication | |||||

| Q16. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 38 (70.4) | 15 (29.6) | 0 (0) | |||

| Q17. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 40 (74.1) | 13 (24.1) | 0 (0) | |||

| Q18. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 38 (70.4) | 16 (29.6) | 0 (0) | |||

| Q19. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 37 (68.5) | 17 (31.5) | 0 (0) | |||

| Q20. | Definitely Yes | Maybe | Definitely No | ||

| 43 (79.6) | 11 (20.4) | 0 (0) | |||

| Video, Mean Rating, SD, Range 1—Very Poor to 6—Excellent | Video Descriptions | Qualitative Feedback |

|---|---|---|

| Communication-Skills Focused Videos | ||

Answering Questions Mean: 4.94 (0.90) Range: 2–6 | Depicts a conversation between a mother and son to demonstrate various verbal and nonverbal techniques that help to provide a nonjudgmental and affirming environment when answering a son’s emergent questions. Constructs addressed: Observational Learning; Self-Efficacy/Perceived Behavioral Control. (Duration: 12:14 min) | “This video was great. I learned how to manage emotions and find a proper way to communicate with my children.” -Claire, mother with a 15 y/o gay son “I like how it talked about most parents are uncomfortable talking to their kids about sex also how our facial expression can tell a lot and to answer the questions with facts take time to think about the answer.”—April, mother of 15 y/o gay child |

Overcoming Communication Barriers Mean: 4.22 (0.98) Range: 3–6 | Nurses address misconceptions about sex communication with children to encourage parents to initiate conversations about sex with their sons. Constructs addressed: Attitudes; Subjective Norms (Duration: 5:00 min) | “It’s such a great topic! It needs to be done much sooner in life… If our culture could be taught to start talking about their bodies at an early age and age appropriately I think it would prevent a lot of issues surrounding the LQBTQ community and beyond.”—Victoria, mother with a 19 y/o gay son “It’s a great video which made me tear up. I would like to share this video to my family members and friends.”—Shawn, father of 14 y/o gay child |

Coming Out and Communication Tips Mean: 5.25 (0.89) Range: 4–6 | Presents various coming out stories. Provides guidance on affirmative responses for parents when sons come out. Constructs addressed: Attitudes; Self-Efficacy/Perceived Behavioral Control (Duration: 4:25 min) | “I really liked hearing each of the adolescents stories of how they came out. I know its incredibly hard for a teen when they come out but the video made me realize its even more complex then I originally thought. I liked the way the information was presented and it also motivated me to want to go research more online.”—Jack, father of 15 y/o gay child “It’s not a easy thing to come out for a teenager. I went through a hard time with my son when he realized he may like a boy.” —Tom, father of 15 y/o bisexual son |

Tips from Parents Like You Mean: 5.09 (0.70) Range: 4–6 | Offers advice on how parents can express their own views about sex in open and inclusive sex communication with their sons. Constructs addressed: Subjective Norms; Attitudes (Duration: 4:45 min) | “I was so moved by this video, and it’s very much like a story that happened in my life.”—Joanne, mother with a 15 y/o gay son “It was encouraging to talk to other parents and again see that surrounding yourself with likeminded people is helpful… I liked how all of the talk was gender and sexuality neutral because all the issues are relevant for all teens, irrespective of gender or sexual orientation.”—Robert, father of 19 y/o gay child |

You’re Normal, Kiddo! Mean: 5.00 (0.82) Range: 4–6 | Normalizes LGBTQ identities and introduces various sexuality and gender-specific terms. Models parental reassurance of GBQ sons and highlights stigma experienced due to societal heteronormativity. Constructs addressed: Observational Learning; Attitudes (Duration: 5:54 min) | “I had never thought body language was important while talking and I agree with the video—it does make a big difference and is significant. The video made me think about the tone and facial expressions I should be using. I also liked the part that dealt with answering my son’s questions with facts that he will understand.”—Jack, father with a 15 y/o gay son “The scroll of terms is a reminder how much there is to learn, and how much we are not taught about sexual orientation and gender identity… I appreciate that the doctor character talked about learning from and along with his children.”—Cynthia, mother of 24 y/o gay child |

When we say “Be safe”… Mean: 4.60 (0.70) Range: 4–6 | Emphasizes importance of ongoing sex communication that is detailed instead of general instructions about safety. Constructs addressed: Attitudes; Self-Efficacy/Perceived Behavioral Control (Duration: 6:20 min) | “I thought it presented a specific scenario that a parent could use as an example for a conversation about being safe. I like the “fail” examples also. Using humor can be a way to lessen the anxiety that might surround the issue.”—Michelle, mother with a 16 y/o queer-identifying child “It’s kind of embarrassing for me to talk with my kids about “safety” since I need to mention a lot of details. They might feel more awkward than me. This video solves the problem perfectly.”—Sheena, mother of 14 y/o gay child |

Setting Rules and the Teenager’s Developing Brain Mean: 5.00 (0.89) Range: 4–6 | Models parental rule-setting that aligns with adolescent brain development. Constructs addressed: Intentions; Observational Learning (Duration: 6:15 min) | “It’s very useful.”—Franklin, father of 20 y/o gay child “The video regarding setting rules and teenagers developing brain did not seem to flow so easy for me. I also didn’t feel like that would be normal conversation between a father and a son.”—Amy, mother of 22 y/o gay child |

| Information-Focused Videos | ||

Before Doing the Deed Mean: 4.55 (0.82) Range: 4–6 | Suggests ways parents can provide sex education and gauge their sons’ readiness to have sex as well as their understanding of consent. Constructs addressed: Observational Learning; Subjective Norms (Duration 5:11: min) | “It’s neat how the parents took a very casual approach while talking about abstinence. Not being preachy and being realistic were also two important approaches discussed in the video that I approved of.”—Brandon, father of 17 y/o gay child “The parent-parent conversation was good. Being surrounded by others who support your view of talking about sex with your kids has to help.”—Robert, father with 19 y/o gay son |

Reassuring Conversations Mean: 5.00 (0.63) Range: 4–6 | Describes potential ways parents can show support to sons who are facing discrimination at school, from extended family members, or in other social spaces. Constructs addressed: Subjective Norms; Observational Learning (Duration: 4:35 min) | “Great video. I wouldn’t change anything.” —Amy, mother of 22 y/o gay child “After watching I took away a few of the points such as making it clear that I can be relied upon and showing my love during our conversations.” —Brandon, father with a 17 y/o gay son |

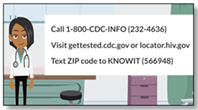

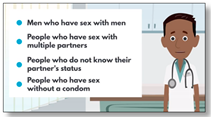

Demystifying HIV Testing Mean: 5.38 (0.52) Range: 5–6 | Provides information on HIV testing, including LGBTQ-friendly testing. Models ways parents can bolster their sons’ autonomy in navigating sexual health care structures. Constructs addressed: Attitudes; Intentions (Duration: 4:53) | “I think one of the most important things discussed was getting rid of the stigma around HIV and testing. The information was clear, straight to the point, and easy to understand.”—Jack, father with a 15 y/o gay son “This is a much harder topic to discuss with our kids. This video is really good. I do think that being part of the LGBT community, my son probably hears more on this topic that straight, cisgender boys, which is really good. Again, my favorite part was the example conversation the mom had with her son.”—Jennifer, mother of 18 y/o bisexual child |

Adolescents, Technology and Communication Mean: 4.90 (0.88) Range: 4–6 | Suggests questions to gauge sons’ understanding of safety concerns with sexting and online dating/hook-ups and provides opportunities to offer tips for navigating these situations. Constructs addressed: Attitudes; Self-Efficacy/Perceived Behavioral Control (Duration 4:42 min) | “I feel exactly the same as the parents in this video. It’s hard to talk about safe sex since you need to let kids know what is unsafe sex.”—Jeremy, father with a 14 y/o gay son “It’s great to have communication about difficult subjects with our teens/young adults, but hard for them to know our desire to help them have safe relationships and to have an exit plan, boundaries, etc. Older dates can sound exciting albeit risky to many teens and young adults.”—Dori, mother of 22 y/o gay child |

HIV and HPV Prevention Mean: 5.60 (0.52) Range: 5–6 | Describes PrEP and the HVP vaccine and CDC guidelines based on age and sexual activity. Constructs addressed: Attitudes; Intentions (Duration 5:19 min) | “Very informative and well-summarized with the most up-to-date medical information. Especially appreciate the PrEP information and I think it may be something not all parents are aware of. My son brought it to my attention.”—Paula, mother with a 21 y/o gay son “I think it was well done on how PrEP is needed for those who are gay. Safe sex is better than being unprotected. That is what I told my son.”—Derek, father of 14 y/o gay child |

Abuse and Victimization Mean: 4.33 (0.50) Range: 4–5 | Demonstrates ways to discuss consent and sexual assault with sons. Offers options for reporting abuse. Constructs addressed: Self-Efficacy/Perceived Behavioral Control; Observational Learning (Duration 5:05 min) | “Good advice on listening without prying or opining. Good that there are contacts for supportive organizations.”—Sarah, mother with a 20 y/o gay son “Safety is a hard topic to talk with child since you need to tell them what activities are not safe in details. This video offers a better choice.”—Shawn, father of 14 y/o gay child |

| Theme | Code and Description |

|---|---|

| Positive Impressions | Step-by-step instructions (n = 15) *. Parents appreciated the methodical way each video broke down a communication process or provided basic information about a topic first before building up to more complex issues. The numerous “sample scripts” parents can use in their everyday lives were regarded as one of the tangible benefits to watching both sets of videos. |

| Short video duration for self-paced viewing and schedule flexibility (n = 8). With 12 of the 13 videos running under 5 min viewing time, parents felt they could watch the videos at their own pace based on their level of knowledge (beginner vs. advanced level).They could also anticipate seeing the entire series at different times depending on their schedule due to the unstructured time commitment. | |

| Normalized parental struggles with non-judgmental approach (n = 8). Many parents appreciated how the videos recognized the overwhelming nature of discussing sensitive sexual health matters with GBQ sons. The reassuring tone throughout the videos that did not judge parents for not having already initiated talks or have a comprehensive understanding of LGBTQ health created a friendly atmosphere to learn. | |

| Diversity of characters and spectrum of family experiences and conundrums (n = 9). Viewers positively regarded the diverse range of animated characters along with the different situations depicted in the videos as seemingly realistic. Parents found the series inclusive of different ethnic/racial individuals with relatable plot lines. | |

| Easy website navigability with apt titles, descriptions, and resources (n = 16). Noting the “clean” layout with ample white space, parents overwhelmingly had no issues exploring the Parents ASSIST website and selecting the videos that interested them based on the titles and descriptions. Parents noted the comprehensive topic-specific resources embedded at the end of each video as well as the broad online links listed on the “Resources” tab of the website. | |

| Compendium of parenting tips for improved communication (n = 5). Parents appreciated the extensiveness of communication tips they heard in the videos, which repeated the value of making up for lost sex talk opportunities, admitting knowledge limitations, and partnering with sons to look up LGBTQ-specific information parents might not have ready answers about. | |

| Acknowledgment that GBQ sons may sometimes know more than parents (n = 3). Noting that youth typically come out to parents after they reach a certain level of comfort with being GBQ, several parents appreciated the recognition that sons often possess more knowledge than their parents do about LGBTQ health issues. Videos that depict sons as informed about rudimentary issues pertaining to their own health were favorably received and evaluated as realistic. | |

Other Positive Feedback

| |

| Negative Impressions | Broad focus and undefined youth age targets (n = 3). Two parents commented on the vast number of topics covered throughout the series that they judged may be too advanced for parents with elementary-age GBQ sons (e.g., PrEP) or too basic for those with sons already in high school or about to go to college (e.g., what the acronym LGBTQ means). These parents suggested clearly identifying the target age range for each video to help plan for when they would be most appropriate to use. |

| Idealized or unrealistic dialogue (n = 3). Two parents reported some of the dialogue they heard as too idealistic, formal, or unrealistic. According to them, youth depicted in the videos seem to speak maturely while most parents in real life would be unable to deliver some of the recommended lines as they seemed too scripted. | |

| Technical glitches (n = 3). Two parents reported experiencing occasional difficulty viewing the videos on their Android phones or tablets. According to them, some videos took a while to load and some of the descriptions did not line up to the appropriate video image. | |

| Lack of content addressing lesbian and bisexual daughters and transgender children (n = 5). A few parents noted that they would have appreciated videos that tackled gender-specific issues (e.g., use of pronouns, transgender health, etc.) or included concerns of families with lesbian or bisexual daughters. | |

Other Negative Feedback

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Flores, D.D.; Hennessy, K.; Rosario, A.; Chung, J.; Wood, S.; Kershaw, T.; Villarruel, A.; Bauermeister, J. Parents ASSIST: Acceptability and Feasibility of a Video-Based Educational Series for Sexuality-Inclusive Communication between Parents and Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Sons. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010379

Flores DD, Hennessy K, Rosario A, Chung J, Wood S, Kershaw T, Villarruel A, Bauermeister J. Parents ASSIST: Acceptability and Feasibility of a Video-Based Educational Series for Sexuality-Inclusive Communication between Parents and Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Sons. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010379

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlores, Dalmacio D., Kate Hennessy, Andre Rosario, Jamie Chung, Sarah Wood, Trace Kershaw, Antonia Villarruel, and Jose Bauermeister. 2022. "Parents ASSIST: Acceptability and Feasibility of a Video-Based Educational Series for Sexuality-Inclusive Communication between Parents and Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Sons" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010379