Evaluating the Factor Structure of the Emotion Dysregulation Scale-Short (EDS-s): A Preliminary Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Emotion Dysregulation

2.4. Binge Eating Severity

2.5. General Psychopathology

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

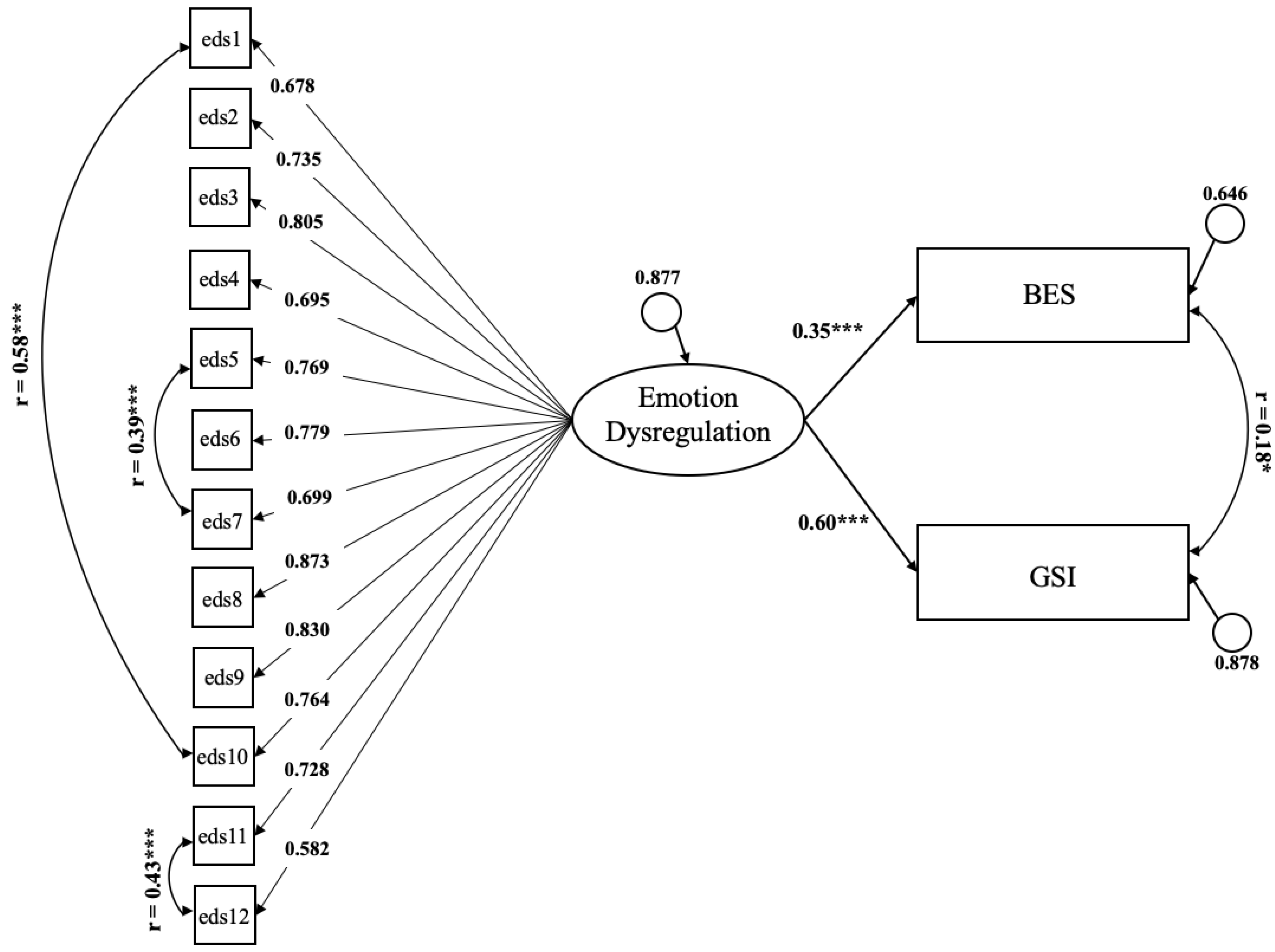

3.1. Dimensionality of the EDS

3.2. Psychometric Properties of the EDS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Italian Version of the EDS-s

| Per Nulla Vero | In Parte Vero | Assolutamente Vero | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mi è spesso difficile calmarmi quando sono agitato | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 2. Quando sono agitato, ho difficoltà a capire quello che provo, mi sento solo male | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 3. Quando mi sento male, ho difficoltà a ricordare qualcosa di positivo, tutto sembra negativo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 4. Le emozioni mi travolgono | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 5. Quando sono agitato, mi sento solo al mondo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 6. Quando sono agitato, ho difficoltà a risolvere i problemi | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 7. Quando sono agitato, ho difficoltà a ricordare che ci sono persone che si preoccupano per me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8. Quando sono agitato, tutto appare come catastrofico o difficile | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 9. Quando sono agitato, ho difficoltà a vedere o ricordare qualcosa di buono su di me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 10. Quando sono agitato, ho difficoltà a calmarmi | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 11. Quando provo emozioni forti, ho difficoltà a pensare in modo chiaro | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 12. Quando provo forti emozioni, prendo spesso delle cattive decisioni | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

References

- Cole, P.M.; Michel, M.K.; Teti, L.O. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1994, 59, 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchaine, T.P.; Cicchetti, D. Emotion dysregulation and emerging psychopathology: A transdiagnostic, transdisciplinary perspective. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Monell, E.; Clinton, D.; Birgegård, A. Emotion dysregulation and eating disorders-Associations with diagnostic presentation and key symptoms. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Sawyer, A.T.; Fang, A.; Asnaani, A. Emotion dysregulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Depress. Anxiety 2012, 29, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, U.; Gardani, M.; Irvine, K.; Allen, S.; Ypsilanti, A.; Lazuras, L.; Drabble, J.; Stevenson, J.C.; Akram, A. Emotion dysregulation mediates the relationship between nightmares and psychotic experiences: Results from a student population. npj Schizophr. 2020, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Subramaniam, M.; Chong, S.A.; Mahendran, R. Maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and positive symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: The mediating role of global emotion dysregulation. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2020, 27, 826–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, G.; Popolo, R.; Montano, A.; Velotti, P.; Perrini, F.; Buonocore, L.; Garofalo, C.; D’Aguanno, M.; Salvatore, G. Emotion dysregulation, symptoms, and interpersonal problems as independent predictors of a broad range of personality disorders in an outpatient sample. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2017, 90, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, B.L.; Lanius, R.A. Chronic complex dissociative disorders and borderline personality disorder: Disorders of emotion dysregulation? Bord. Pers. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2014, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.R.; Fergus, T.A.; Orcutt, H.K. An Examination of the Latent Structure of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2012, 34, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, J.C.; Charak, R.; Elhai, J.D.; Allen, J.G.; Frueh, B.C.; Oldham, J.M. Construct validity and factor structure of the difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale among adults with severe mental illness. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 58, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallion, L.S.; Steinman, S.; Tolin, D.F.; Diefenbach, G.J. Psychometric Properties of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) and Its Short Forms in Adults With Emotional Disorders. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, D.; Yoo, S.H.; Nakagawa, S. Culture, emotion regulation, and adjustment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 94, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melka, S.E.; Lancaster, S.L.; Bryant, A.R.; Rodriguez, B.F. Confirmatory factor and measurement invariance analyses of the emotion regulation questionnaire. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaapen, D.L.; Waters, F.; Brummer, L.; Stopa, L.; Bucks, R.S. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Validation of the ERQ-9 in two community samples. Psychol. Assess. 2014, 26, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltink, J.; Glaesmer, H.; Canterino, M.; Wölfling, K.; Knebel, A.; Kessler, H.; Brähler, E.; Beutel, M.E. Regulation of emotions in the community: Suppression and reappraisal strategies and its psychometric properties. GMS Psycho-Soc.-Med. 2011, 8, Doc09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, A.; Stevens, J.; Fani, N.; Bradley, B. Construct validity of a short, self report instrument assessing emotional dysregulation. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 225, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradley, B.; DeFife, J.A.; Guarnaccia, C.; Phifer, J.; Fani, N.; Ressler, K.J.; Westen, D. Emotion Dysregulation and Negative Affect. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christ, C.; De Waal, M.M.; Dekker, J.J.M.; van Kuijk, I.; van Schaik, D.J.F.; Kikkert, M.J.; Goudriaan, A.E.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Messman-Moore, T.L. Linking childhood emotional abuse and depressive symptoms: The role of emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, E.C.; Nishimi, K.; Gomez, S.H.; Powers, A.; Bradley, B. Developmental timing of trauma exposure and emotion dysregulation in adulthood: Are these sensitive periods when traums is most harmful? J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekawi, Y.; Watson-Singleton, N.N.; Kuzyk, E.; Dixon, H.D.; Carter, S.; Bradley-Davino, B.; Fani, N.; Michopoulos, V.; Powers, A. Racial discrimination and posttraumatic stress: Examining emotion dysregulation as a mediator in an African American community sample. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2020, 11, 1824398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pencea, I.; Munoz, A.P.; Maples-Keller, J.L.; Fiorillo, D.; Schultebraucks, K.; Galatzer-Levy, I.; Rothbaum, B.O.; Ressler, K.J.; Stevens, J.S.; Michopoulos, V.; et al. Emotion dysregulation is associated with increased prospective risk for chronic PTSD development. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 121, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heene, M.; Hilbert, S.; Draxler, C.; Ziegler, M.; Bühner, M. Masking misfit in confirmatory factor analysis by increasing unique variances: A cautionary note on the usefulness of cutoff values of fit indices. Psychol. Methods 2011, 16, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperatori, C.; Innamorati, M.; Lamis, D.A.; Contardi, A.; Continisio, M.; Castelnuovo, G.; Manzoni, G.M.; Fabbricatore, M. Factor Structure of the Binge Eating Scale in a Large Sample of Obese and Overweight Patients Attending Low Energy Diet Therapy. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2016, 24, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adawi, M.; Zerbetto, R.; Re, T.S.; Bisharat, B.; Mahamid, M.; Amital, H.; Del Puente, G.; Bragazzi, N.L. Psychometric properties of the Brief Symptom Inventory in nomophobic subjects: Insights from preliminary confirmatory factor, exploratory factor, and clustering analyses in a sample of healthy Italian volunteers. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample Size Requirements for Structural Equation Models: An Evaluation of Power, Bias, and Solution Propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Chou, C.-P. Practical Issues in Structural Modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1987, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormally, J.; Black, S.; Daston, S.; Rardin, D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Melisaratos, N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychol. Med. 1983, 13, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Cleary, P.A. Confirmation of the dimensional structure of the SCL-90-R: A study in construct validation. J. Clin. Psychol. 1977, 33, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User’s Guide (Version 8); Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 25.0, Released 2017; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.Y. Evaluating Cutoff Criteria of Model Fit Indices for Latent Variable Models with Binary and Continuous Outcomes; University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd edn. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A (Stat. Soc.) 2012, 175, 828–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. A note on guttman’s lower bound for the number of common factors. Br. J. Stat. Psychol. 1961, 14, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsamo, M.; Macchia, A.; Carlucci, L.; Picconi, L.; Tommasi, M.; Gilbert, P.; Saggino, A. Measurement of External Shame: An Inside View. J. Pers. Assess. 2015, 97, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermida, R. The problem of allowing correlated errors in structural equation modeling: Concerns and considerations. Comput. Methods Soc. Sci. 2015, 3, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, L.; Bliss-Moreau, E. She’s emotional. He’s having a bad day: Attributional explanantions for emotion stereotypes. Emotion 2009, 9, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McRae, K.; Ochsner, K.N.; Mauss, I.B.; Gabrieli, J.J.D.; Gross, J.J. Gender Differences in Emotion Regulation: An fMRI Study of Cognitive Reappraisal. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2008, 11, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soto, C.J.; John, O.P.; Gosling, S.D.; Potter, J. Age differences in personality traits from 10 to 65: Big Five domains and facets in a large cross-sectional sample. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zimmermann, P.; Iwanski, A. Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: Age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2014, 38, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, S.E.; Horvath, S.A. Emotion dysregulation across the spectrum of pathological eating: Comparisons among women with binge eating, overeating, and loss of control eating. Eat. Disord. 2018, 26, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, A.C.; Jackson, J.J.; Barch, D.M.; Tillman, R.; Luby, J.L. Excitability and irritability in preschoolers predicts later psychopathology: The importance of positive and negative emotion dysregulation. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, U.; Chen, E.; Neighbors, C.; Hunter, D.; Lo, T.; Larimer, M. Difficulties regulating emotions: Do binge eaters have fewer strategies to modulate and tolerate negative affect? Eat. Behav. 2007, 8, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Mennin, D.S.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion dysregulation and adolescent psychopathology: A prospective study. Behav. Res. Ther. 2011, 49, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Keenan, K. Emotion dysregulation as a risk factor for child psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2000, 7, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Count/M | %/(SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age M(SD) | 36.02 | (15.56) |

| Gender n/% | ||

| Men | 319 | 29.3% |

| Women | 768 | 70.7% |

| School attainment ≥ 13 years n/% | 607 | 55.8% |

| Job status n/% | ||

| Employed | 513 | 47.2% |

| Unemployed | 207 | 19.0% |

| Student | 363 | 33.4% |

| Marital status n/% | ||

| Married or in a stable relationship | 386 | 35.5% |

| Single | 693 | 63.8% |

| EDS-s M(SD) | 37.98 | (15.67) |

| Variables | Count/M | %/(SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age M (SD) | 36.17 | (15.17) |

| Gender n/% | ||

| Men | 114 | 38.6% |

| Women | 181 | 61.4% |

| School attainment ≥ 13 years n/% | 125 | 42.4% |

| Job status n/% | ||

| Employed | 162 | 54.9% |

| Unemployed | 34 | 11.5% |

| Student | 99 | 33.6% |

| Marital status n/% | ||

| Married or in a stable relationship | 112 | 38.0% |

| Single | 183 | 62.0% |

| EDS-s M(SD) | 35.68 | (14.94) |

| BES M(SD) | 8.29 | (6.98) |

| GSI M(SD) | 34.21 | (26.38) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raimondi, G.; Imperatori, C.; Fabbricatore, M.; Lester, D.; Balsamo, M.; Innamorati, M. Evaluating the Factor Structure of the Emotion Dysregulation Scale-Short (EDS-s): A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010418

Raimondi G, Imperatori C, Fabbricatore M, Lester D, Balsamo M, Innamorati M. Evaluating the Factor Structure of the Emotion Dysregulation Scale-Short (EDS-s): A Preliminary Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):418. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010418

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaimondi, Giulia, Claudio Imperatori, Mariantonietta Fabbricatore, David Lester, Michela Balsamo, and Marco Innamorati. 2022. "Evaluating the Factor Structure of the Emotion Dysregulation Scale-Short (EDS-s): A Preliminary Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010418

APA StyleRaimondi, G., Imperatori, C., Fabbricatore, M., Lester, D., Balsamo, M., & Innamorati, M. (2022). Evaluating the Factor Structure of the Emotion Dysregulation Scale-Short (EDS-s): A Preliminary Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010418