Association of Received Intergenerational Support with Subjective Well-Being among Elderly: The Mediating Role of Optimism and Sex Differences

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Intergenerational Support

2.2.2. Optimism

2.2.3. Subjective Well-Being

2.3. Analytical Approach

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

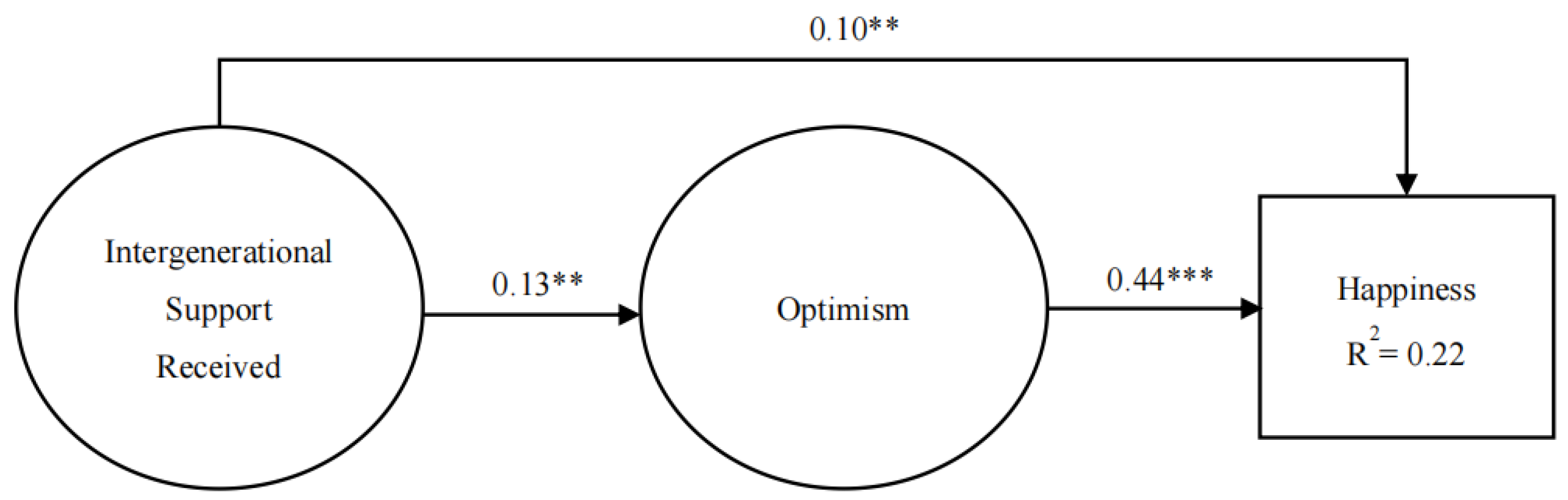

3.2. Overall Model

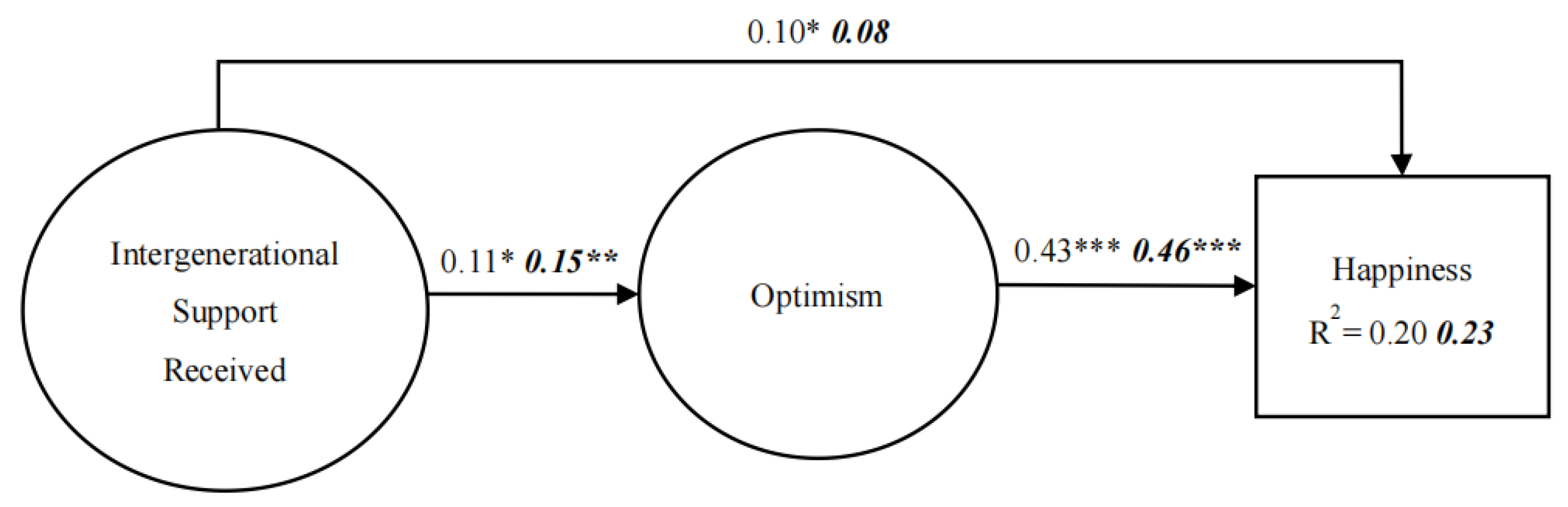

3.3. Sex Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Intergenerational Support and Subjective Well-Being

4.2. Mediating Role of Optimism

4.3. Sex Differences

4.4. Limitations and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Khalek, A.M. Quality of life, subjective well-being, and religiosity in Muslim college students. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.; Oishi, S. Recent findings on subjective well-being. Indian J. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 24, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, S.-P.; Kim, B.-H. Relationship Between Social Support and Subjective Well-being of the Urban Elderly People. J. Korea Acad. -Ind. Coop. Soc. 2021, 22, 367–377. [Google Scholar]

- Muarifah, A.; Widyastuti, D.A.; Fajarwati, I. The effect of social support on single mothers’ subjective well-being and its implication for counseling. J. Kaji. Bimbing. Dan Konseling 2019, 4, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, X.; Qiao, Y.; Zhao, L.; He, Q.; Zhang, L.; Liang, Y. Effect of intergenerational and intragenerational support on perceived health of older adults: A population-based analysis in rural China. Fam. Pract. 2014, 31, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, H.; Mao, X.; Lai, D. East or West, home is the best: Effect of intergenerational and social support on the subjective well-being of older adults: A comparison between migrants and local residents in Shenzhen, China. Ageing Int. 2015, 40, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Sheng, Y. Social support network, social support, self-efficacy, health-promoting behavior and healthy aging among older adults: A pathway analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 85, 103934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M.; Bengtson, V.L. Does intergenerational social support influence the psychological well-being of older parents? The contingencies of declining health and widowhood. Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 38, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Xiao, J.; Dai, X.; Han, Y.; Liu, Y. Effect of family “upward” intergenerational support on the health of rural elderly in China: Evidence from Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Silverstein, M. Intergenerational social support and the psychological well-being of older parents in China. Res. Aging 2000, 22, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Jeon, G.-S.; Jang, K.-S. Gender differences in the impact of intergenerational support on depressive symptoms among older adults in korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, Z.; Silverstein, M. Intergenerational support and depression among elders in rural China: Do daughters-in-law matter? J. Marriage Fam. 2008, 70, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, H. Intergenerational exchange and mental health in later-life—the case of older Jewish Israelis. Aging Ment. Health 2004, 8, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.D. Subjective Well-being and Intergenerational Support Exchange in Old Age in Rural Vietnam. Wieś I Rol. 2020, 186, 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Öztop, H.; Şener, A.; Güven, S.; Doğan, N. Influences of intergenerational support on life satisfaction of the elderly: A Turkish sample. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2009, 37, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R.; Lowenstein, A. Solidarity between generations and elders’ life satisfaction: Comparing Jews and Arabs in Israel. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2012, 10, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.R.; Ellithorpe, E. Intergenerational exchange and subjective well-being among the elderly. J. Marriage Fam. 1982, 44, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Miao, G.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, S. Relationship between Children’s Intergenerational Emotional Support and Subjective Well-Being among Middle-Aged and Elderly People in China: The Mediation Role of the Sense of Social Fairness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Kwok, C.L.; Law, Y.W.; Yip, P.S.; Cheng, Q. Intergenerational support, satisfaction with parent–child relationship and elderly parents’ life satisfaction in Hong Kong. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q. Intergeneration social support affects the subjective well-being of the elderly: Mediator roles of self-esteem and loneliness. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Jing, X.; Wallace, R.; Jiang, X.; Kim, D.-s. Core self-evaluation: Linking career social support to life satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 112, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Ling, Y.; Cai, T. Core self-evaluations and coping styles as mediators between social support and well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 88, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol. 1985, 4, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, K.M. How positive is their future? Assessing the role of optimism and social support in understanding mental health symptomatology among homeless adults. Stress Health 2017, 33, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karademas, E.C. Self-efficacy, social support and well-being: The mediating role of optimism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnen, T.-W.; Chiu, Y.-C.; Hsu, Y. Perception of social support provided by coaches, optimism/pessimism, and psychological well-being: Gender differences and mediating effect models. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2021, 16, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestler-Peleg, M.; Lavenda, O. Optimism as a mediator of the association between social support and peripartum depression among mothers of neonatal intensive care unit hospitalized preterm infants. Stress Health 2021, 37, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, A.; Katz, R.; Gur-Yaish, N. Reciprocity in parent–child exchange and life satisfaction among the elderly: A cross-national perspective. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 865–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonucci, T.C.; Akiyama, H. An examination of sex differences in social support among older men and women. Sex Roles 1987, 17, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M.; Gans, D.; Yang, F.M. Intergenerational support to aging parents: The role of norms and needs. J. Fam. Issues 2006, 27, 1068–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batz, C.; Tay, L. Gender differences in subjective well-being. In Handbook of Well-Being; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R.; Marbaniang, S.P.; Srivastava, S.; Kumar, P.; Chauhan, S.; Simon, D.J. Gender differential in low psychological health and low subjective well-being among older adults in India: With special focus on childless older adults. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Shukla, A. Optimism among institutionalized elderly: A gender study. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2014, 5, 1198–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino, B.N.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 119, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Song, L.; Feldman, M.W. Intergenerational support and subjective health of older people in rural China: A gender-based longitudinal study. Australas. J. Ageing 2009, 28, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Li, L. The Chinese general social survey (2003-8) sample designs and data evaluation. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 45, 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.C.; Cheung, H.; Lee, W.m.; Yu, H. The utility of the revised Life Orientation Test to measure optimism among Hong Kong Chinese. Int. J. Psychol. 1998, 33, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S.; Bridges, M.W. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Gu, M. Relationship between mindfulness and positive affect of Chinese older adults: Optimism as mediator. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2017, 45, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.C.; Yue, X. Measuring optimism in Hong Kong and mainland Chinese with the revised Life Orientation Test. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2000, 28, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J.L. IBM SPSS Amos, (Version 25.0); IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A. Social networks and social support among older people and implications for emotional well-being and psychiatric morbidity. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 1994, 6, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, X. Intergenerational relationship, family social support, and depression among Chinese elderly: A structural equation modeling analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 248, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicirelli, V.G. Attachment and obligation as daughters’ motives for caregiving behavior and subsequent effect on subjective burden. Psychol. Aging 1993, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murayama, Y.; Ohba, H.; Yasunaga, M.; Nonaka, K.; Takeuchi, R.; Nishi, M.; Sakuma, N.; Uchida, H.; Shinkai, S.; Fujiwara, Y. The effect of intergenerational programs on the mental health of elderly adults. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Segerstrom, S.C. Optimism. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garner, M.J.; McGregor, B.A.; Murphy, K.M.; Koenig, A.L.; Dolan, E.D.; Albano, D. Optimism and depression: A new look at social support as a mediator among women at risk for breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 1708–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmann, M.; Antoniw, K.; Hartung, F.M.; Renner, B. Social support as mediator of the stress buffering effect of optimism: The importance of differentiating the recipients’ and providers’ perspective. Eur. J. Personal. 2011, 25, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, É.; McMahon, J.; Gallagher, S. Optimism and benefit finding in parents of children with developmental disabilities: The role of positive reappraisal and social support. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 65, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri Sheykhangafshe, F.; Shabahang, R. Prediction of psychological wellbeing of elderly people based on spirituality, social support, and optimism. J. Relig. Health 2020, 7, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, S.J.; Goodwin, A.D. Optimism and well-being in older adults: The mediating role of social support and perceived control. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2010, 71, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, H.E.; Daniel, F. Optimism and well-being among institutionalized older adults. GeroPsych 2018, 31, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reker, G.T. Personal meaning, optimism, and choice: Existential predictors of depression in community and institutional elderly. Gerontol. 1997, 37, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sagi, L.; Bareket-Bojmel, L.; Tziner, A.; Icekson, T.; Mordoch, T. Social support and well-being among relocating women: The mediating roles of resilience and optimism. Rev. Psicol. Del Trab. Organ. 2021, 37, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakey, B.; Orehek, E. Relational regulation theory: A new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 118, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rodriguez, N.; Flores, R.T.; London, E.F.; Bingham Mira, C.; Myers, H.F.; Arroyo, D.; Rangel, A. A test of the main-effects, stress-buffering, stress-exacerbation, and joint-effects models among Mexican-origin adults. J. Lat. Psychol. 2019, 7, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Intergenerational relations and Chinese elderly’s subjective well-being: An analysis of differentials by gender and residence. Chin. J. Sociol. 2016, 2, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J.S. The gender similarities hypothesis. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carrillo, A.; Rubio-Aparicio, M.; Molinari, G.; Enrique, Á.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Baños, R.M. Effects of the best possible self intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall | Sex Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| Received intergenerational support | 8.61 | 8.38 | 8.81 |

| (2.64) | (2.56) | (2.68) | |

| Received financial support | 2.91 | 2.85 | 2.96 |

| (1.18) | (1.15) | (1.21) | |

| Received instrumental support | 2.77 | 2.71 | 2.82 |

| (1.18) | (1.16) | (1.21) | |

| Received emotional support | 2.93 | 2.82 | 3.03 |

| (1.02) | (1.00) | (1.03) | |

| Optimism | 11.43 | 11.47 | 11.39 |

| (1.81) | (1.77) | (1.84) | |

| Subjective well-being | 3.90 | 3.88 | 3.91 |

| (0.85) | (0.88) | (0.83) | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Received financial support | 1 | 0.39 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| 2. Received instrumental support | 1 | 0.49 ** | 0.06 * | 0.11 ** | |

| 3. Received emotional support | 1 | 0.14 ** | 0.13 ** | ||

| 4. Optimism | 1 | 0.37 ** | |||

| 5. Subjective well-being | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, Z.; Chen, J.-K. Association of Received Intergenerational Support with Subjective Well-Being among Elderly: The Mediating Role of Optimism and Sex Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137614

Pan Z, Chen J-K. Association of Received Intergenerational Support with Subjective Well-Being among Elderly: The Mediating Role of Optimism and Sex Differences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(13):7614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137614

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Zixin, and Ji-Kang Chen. 2022. "Association of Received Intergenerational Support with Subjective Well-Being among Elderly: The Mediating Role of Optimism and Sex Differences" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 13: 7614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137614

APA StylePan, Z., & Chen, J.-K. (2022). Association of Received Intergenerational Support with Subjective Well-Being among Elderly: The Mediating Role of Optimism and Sex Differences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 7614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137614