Exploring Readiness towards Effective Implementation of Safety and Health Measures for COVID-19 Prevention in Nakhon-Si-Thammarat Community-Based Tourism of Southern Thailand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Community Readiness Assessment (CRA)

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of CBT Settings and Participants

3.2. Community Readiness Stage

3.3. Theme One: Community Knowledge of the SHA Implementation Efforts

Subtheme: Inadequate Knowledge of SHA Protocol, Activities, and Details

“The provincial tourism has also come to our club, focusing on the COVID-19 prevention actions, such as temperature checks, using alcohol to clean our hands, sanitizing our areas, and wearing face masks. Actually, we do it in our daily lives and when we receive tourists during COVID-19 pandemic in the early year. I need to do SHA standards, but how can I start? I and our team do not clear for the action process…”.(Participant 10)

3.4. Theme Two: Leadership

3.4.1. Subtheme: Strong Motivation of the Team Leaders

“I try to plan things according to its standards, although I didn’t know the details. I think SHA will make the benefit to our community not only for COVID-19 prevention but also the benefit of tourism income.”(Participant 1)

“I think we have to start from ourselves…other members don’t know SHA well too, whether its’ going to be done initially, it must be done for an example first, then the members are able to follow.”(Participant 10)

3.4.2. Subtheme: Peer Group of Village Health Volunteer

“At the early phase of pandemic, I didn’t know how to prevent the COVID-19 in my homestay services; however, VHV came to join information and prevention activities with our CBT, such as notifying the community epidemic, communicating the public health measures…”.(Participant 12)

3.5. Theme Three: Community Climate

3.5.1. Subtheme: Strong Community Engagement

“I believed that our club members could drive the SHA efforts. We have to set an example and then expand it to the various activities of the community members because all sectors have to do the same”(Participant 8)

3.5.2. Subtheme: Inaccessibility of the SHA Efforts

“I perceived the SHA protocol, but our members such as small shops and restaurants may not access. I thought the provincial tourism government should communicate more information to the CBT groups. This action might initiate before the full implementation of SHA.”(Participant 1)

3.6. Theme Four: Community Knowledge about the Issues

3.6.1. Subtheme: The Support of Local Tourism and Health Organisation

“I haven’t started the process yet. But I know that other places have already done it, a sample place. There is a tourism operator as a mentor and training from public health officials.”(Participant 3)

3.6.2. Subtheme: The SHA Badge Represents the Safety and Sanitation of Community Tourism Management

“I used to do homestay standards from travel agencies. SHA as public health standards were met during this pandemic. I would be ready to do it, although its’ protocols are complex.”(Participant 15)

3.7. Theme Five: Resources Related Issues

Subtheme: Personnel Support and Strengthen Peer Assessment Team

“I think we already have enough resources. In the community, we can support everything—materials, equipment, and staff. However, that would be great, if we have a training programme before starting or experts to assist with the implementation.”(Participant 10)

3.8. Limitations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBT | Community-based tourism |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease of 2019 |

| CRA | Community Readiness Assessment |

| CRM | Community Readiness Model |

| PHEIC | Public Health Emergency of International Concern |

| SHA | Safety and Health Administration |

| TAT | Tourism Authority of Thailand |

| VHV | Village Health Volunteer |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soliku, O.; Kyiire, B.; Mahama, A.; Kubio, C. Tourism amid COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts and implications for building resilience in the eco-tourism sector in Ghana’s Savannah region. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adane, D.; Yeshaneh, A.; Wassihun, B.; Gasheneit, A. Level of community readiness for the prevention of covid-19 pandemic and associated factors among residents of awi zone, ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 1509–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanani, R.; Rahman, A.Z.; Kristanto, Y. COVID-19 and Adaptation Strategies in Community-Based Tourism: Insights from Community-Based Tourism Sector in Central Java. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 317, 01054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiana, Y.; Pramono, R.; Brian, R. Adaptation Strategy of Tourism Industry Stakeholders during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study in Indonesia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 0213–0223. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Tourism and Sports. Report on the Economic Conditions of Tourism in the 3rd Quarter of 2019. Available online: https://www.mots.go.th/download/TourismEconomicReport/2-1TourismEconomic2(2562).pdf (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Sriwilai, S.; Thongsri, R. The Effects of the Spread of COVID-19 Pandemic on Thai Tourism. J. Leg. Entity Manag. Local Innov. 2021, 7, 405–416. [Google Scholar]

- Krajangchom, S.; Sangkakorn, K.; Poonsukcharoen, N. The Adaptation Strategy of Tourism in Upper North of Thailand under the COVID-19 Pandemic. Univ. Thai Chamb. Commer. J. 2020, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- World Travel & Tourism Council. Travel & Tourism Economic Impact from COVID-19: Global Data. Available online: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Tourism Authority of Thailand. Amazing Thailand Safety and Health Administration. Available online: https://web.thailandsha.com/index (accessed on 28 January 2021).

- Maqbool, A.; Khan, N.Z. Analyzing barriers for implementation of public health and social measures to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 disease using DEMATEL method. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, R.; Alqahtani, S.S.; Albarraq, A.A.; Meraya, A.M.; Tripathi, P.; Banji, D.; Alshahrani, S.; Ahsan, W.; Alnakhli, F.M. Awareness and Preparedness of COVID-19 Outbreak Among Healthcare Workers and Other Residents of South-West Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Public Health 2020. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Tourism and Sports. Summary Report on the Preparation of National Accounting for Tourism Fiscal Year 2020. Available online: https://www.mots.go.th/download/article/article_20211001101334.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Mothonthil, S. Community-Based Tourism, the Way to Sustainability. Bangkok, Thailand. Available online: https://www.gsbresearch.or.th/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/GR_report_travel_detail.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Mtapuri, O.; Giampiccoli, A. Tourism, community-based tourism and ecotourism: A definitional problematic. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2019, 101, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism Authority of Thailand. Thailand Tourism Promotion Action Plan for the Year 2021. Available online: https://api.tat.or.th/upload/live/about_tat/8674/สรุปแผนปฏิบัติการ_2564_update_01-10-2021.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Nakhon Si Thammarat Provincial Tourism and Sports Office. Thailand Tourism Directory. Available online: https://nakhonsi.mots.go.th/ (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Edwards, R.W.; Jumper-thurman, P.; Plested, B.A.; Oetting, E.R.; Swanson, L. Community Readiness: Research to practice. J. Community Psychol. 2000, 28, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oetting, E.R.; Jumper-Thurman, P.; Plested, B.; Edwards, R.W. Community readiness and health services. Subst. Use Misuse 2001, 36, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansefort, D.; Brand, T.; Princk, C.; Zeeb, H. Community readiness for the promotion of physical activity in older adults—a cross-sectional comparison of rural and urban communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oetting, E.R.; Plested, B.A.; Edwards, R.W. Community Readiness for Community Change, 2nd ed.; Colorado State University Fort Collins: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peercy, M.; Gray, J.; Thurman, P.J.; Plested, B. Community Readiness: An Effective Model for Tribal Engagement in Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Fam. Community Health 2010. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Ali, A.; Shi, H.; Siddique, R.; Shabana; Nabi, G.; Hu, J.; Wang, T.; Dong, M.; Zaman, W.; et al. COVID-19: Clinical aspects and therapeutics responses. Saudi Pharm. J. 2020, 28, 1004–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanezi, F.; Aljahdali, A.; Alyousef, S.M.; Alrashed, H.; Mushcab, H.; AlThani, B.; Alghamedy, F.; Alotaibi, H.; Saadah, A.; Alanzi, T. A comparative study on the strategies adopted by the United Kingdom, India, China, Italy, and Saudi Arabia to contain the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2020, 12, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.P.; Meng, S.; Wu, Y.J.; Mao, Y.P.; Ye, R.X.; Wang, Q.Z.; Sun, C.; Sylvia, S.; Rozelle, S.; Raat, H.; et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of COVID during the early outbreak period. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, W.; Saqib, S.; Ullah, F.; Ayaz, A.; Ye, J. COVID-19: Phylogenetic approaches may help in finding resources for natural cure. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 2783–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, P.; Serry, T. Making sense of qualitative data. In Research Methods in Health: Foundations for Evidence-Based Practice; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: South Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2017; pp. 421–436. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. What Are Public Health and Social Health Measures and Why Are They Still Needed at This Stage in the COVID-19 Pandemic? Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Health-systems/health-systems-governance/news/news/2021/11/what-are-public-health-and-social-health-measures-and-why-are-they-still-needed-at-this-stage-in-the-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Asemahagn, M.A. Factors determining the knowledge and prevention practice of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 in Amhara region, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional survey. Trop. Med. Health 2020. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidamo, N.B.; Hussen, S.; Shibiru, T.; Girma, M.; Shegaze, M.; Mersha, A.; Fikadu, T.; Gebru, Z.; Andarge, E.; Glagn, M.; et al. Exploring barriers to effective implementation of public health measures for prevention and control of COVID-19 pandemic in gamo zone of southern ethiopia: Using a modified tanahashi model. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehualashet, S.S.; Asefa, K.K.; Mekonnen, A.G.; Gemeda, B.N.; Shiferaw, W.S.; Aynalem, Y.A.; Bilchut, A.H.; Derseh, B.T.; Mekuria, A.D.; Mekonnen, W.N.; et al. Predictors of adherence to COVID-19 prevention measure among communities in North Shoa Zone, Ethiopia based on health belief model: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246006. [Google Scholar]

- Wanzira, H.; Naiga, S.; Mulebeke, R.; Bukenya, F.; Nabukenya, M.; Omoding, O.; Echodu, D.; Yeka, A. Community facilitators and barriers to a successful implementation of mass drug administration and indoor residual spraying for malaria prevention in Uganda: A qualitative study. Malar. J. 2018, 17, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coroiu, A.; Moran, C.; Campbell, T.; Geller, A.C. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to social distancing recommendations during COVID-19 among a large international sample of adults. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nzaji, M.K.; Mwamba, G.N.; Miema, J.M.; Umba, E.K.N.; Kangulu, I.; Ndala, D.; Mukendi, P.C.; Mutombo, D.K.; Kabasu, M.; Katala, M.K.; et al. Predictors of non-adherence to public health instructions during the covid-19 pandemic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallari, E.; Lasco, G.; Sayman, D.J.; Amit, A.M.L.; Balabanova, D.; McKee, M.; Mendoza, J.; Palileo-Villanueva, L.; Renedo, A.; Seguin, M.; et al. Connecting communities to primary care: A qualitative study on the roles, motivations and lived experiences of community health workers in the Philippines. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martiskainen, M. The role of community leadership in the development of grassroots innovations. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 22, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Disability Considerations during the COVID-19 Outbreak; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieden, T.R. Six components necessary for effective public health program implementation. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Number | Age | Sex | Establishment Types | Role in CBT | Main/Co-Occupation | Religion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural fishing community | 1 | 50 | Male | Recreational activity | Head of rural fishing village | Artisanal fisheries | Islam |

| 2 | 54 | Female | Restaurant | Restaurant owner | Artisanal fisheries | Islam | |

| 3 | 26 | Male | Restaurant | Restaurant owner | Restaurant owner | Buddhism | |

| 4 | 37 | Male | Restaurant | Restaurant owner and Head of rural fishing village | Restaurant owner | Islam | |

| Sub-urban orchard community | 5 | 56 | Male | Recreational activity | Souvenir shop owner | Pottery owner | Buddhism |

| 6 | 46 | Male | Recreational activity | Orchard owner | Orchard owner | Buddhism | |

| 7 | 46 | Female | Recreational activity | Orchard owner | Orchard owner | Buddhism | |

| 8 | 22 | Female | Recreational activity | Head of sub-urban orchard village | Local government officer | Buddhism | |

| Rural mountain community | 9 | 51 | Female | Recreational activity | Batik painting shop owner | Restaurant owner | Buddhism |

| 10 | 52 | Female | Recreational activity | Head of rural mountain village | General | Buddhism | |

| 11 | 39 | Female | Recreational activity | Mushroom farm owner | Mushroom farm owner | Buddhism | |

| 12 | 69 | Female | Homestay | Homestay owner | Homestay owner | Buddhism | |

| 13 | 68 | Male | Homestay | Homestay owner | Homestay owner | Buddhism | |

| 14 | 64 | Female | Homestay | Homestay owner | Homestay owner | Buddhism | |

| 15 | 55 | Female | Homestay | Homestay owner | Homestay owner | Buddhism |

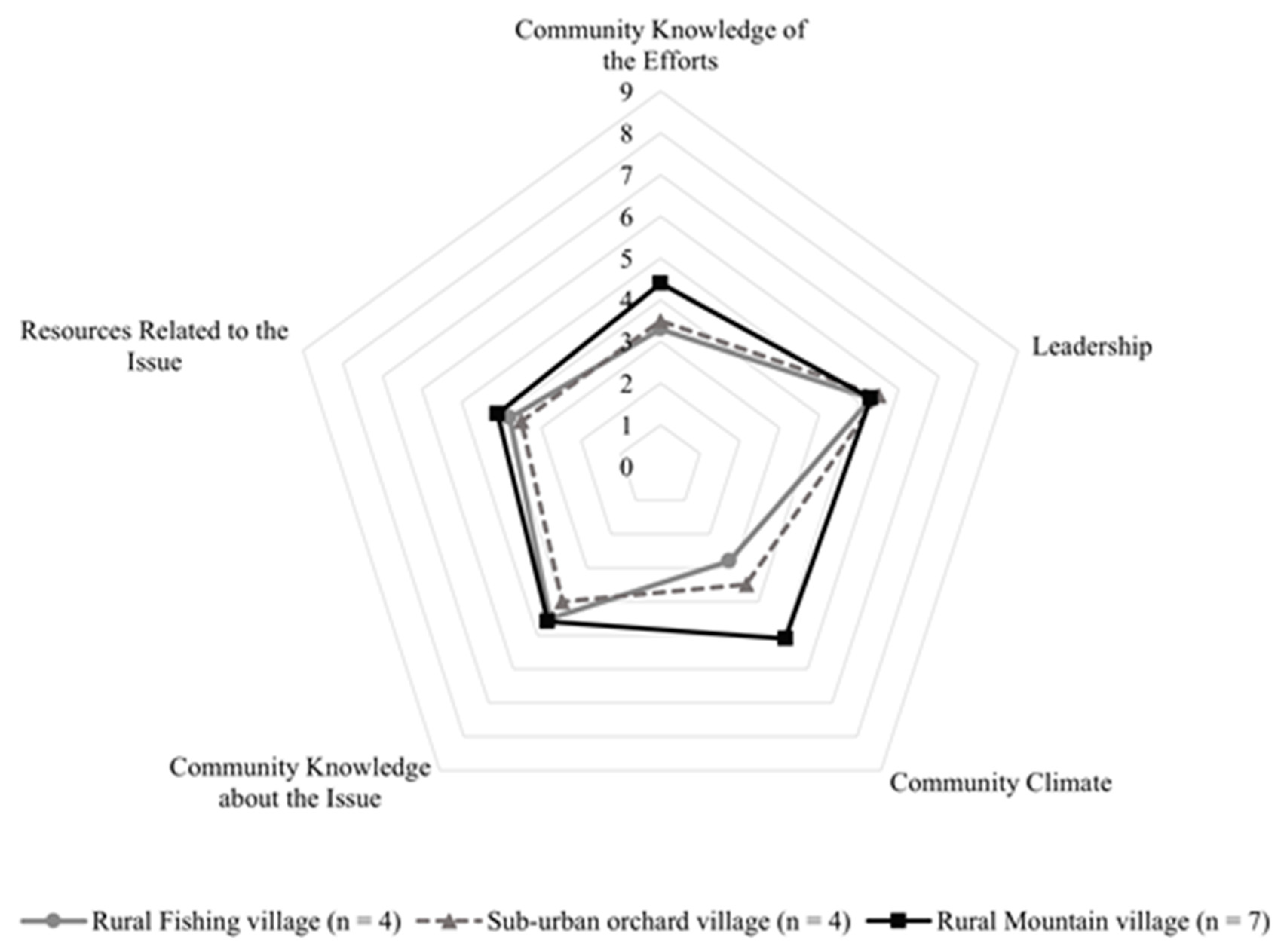

| Main Themes (Community Readiness Dimensions) | Subthemes | CRA Scores (n = 15) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | ||

| Community knowledge of the SHA implementation efforts | Inadequate knowledge of SHA protocol, activities, and details | 3.9 | 1.1 |

| Leadership | Strong motivation of the team leaders | 5.3 | 0.7 |

| Peer group of village health volunteer | |||

| Community climate | Strong community engagement | 4.1 | 1.7 |

| Inaccessibility of the SHA efforts | |||

| Community knowledge about the issue | The support of local tourism and health organisation | 4.4 | 0.6 |

| The SHA badge represents the safety and sanitation of community tourism management | |||

| Resources related to the issue | Personnel support and strengthen peer assessment team | 3.9 | 0.6 |

| Overall readiness level * | 4.32 | 0.94 | |

| Stage of readiness | Pre-planning | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bumyut, A.; Thanapop, S.; Suwankhong, D. Exploring Readiness towards Effective Implementation of Safety and Health Measures for COVID-19 Prevention in Nakhon-Si-Thammarat Community-Based Tourism of Southern Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10049. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610049

Bumyut A, Thanapop S, Suwankhong D. Exploring Readiness towards Effective Implementation of Safety and Health Measures for COVID-19 Prevention in Nakhon-Si-Thammarat Community-Based Tourism of Southern Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10049. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610049

Chicago/Turabian StyleBumyut, Apirak, Sasithorn Thanapop, and Dusanee Suwankhong. 2022. "Exploring Readiness towards Effective Implementation of Safety and Health Measures for COVID-19 Prevention in Nakhon-Si-Thammarat Community-Based Tourism of Southern Thailand" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10049. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610049

APA StyleBumyut, A., Thanapop, S., & Suwankhong, D. (2022). Exploring Readiness towards Effective Implementation of Safety and Health Measures for COVID-19 Prevention in Nakhon-Si-Thammarat Community-Based Tourism of Southern Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10049. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610049