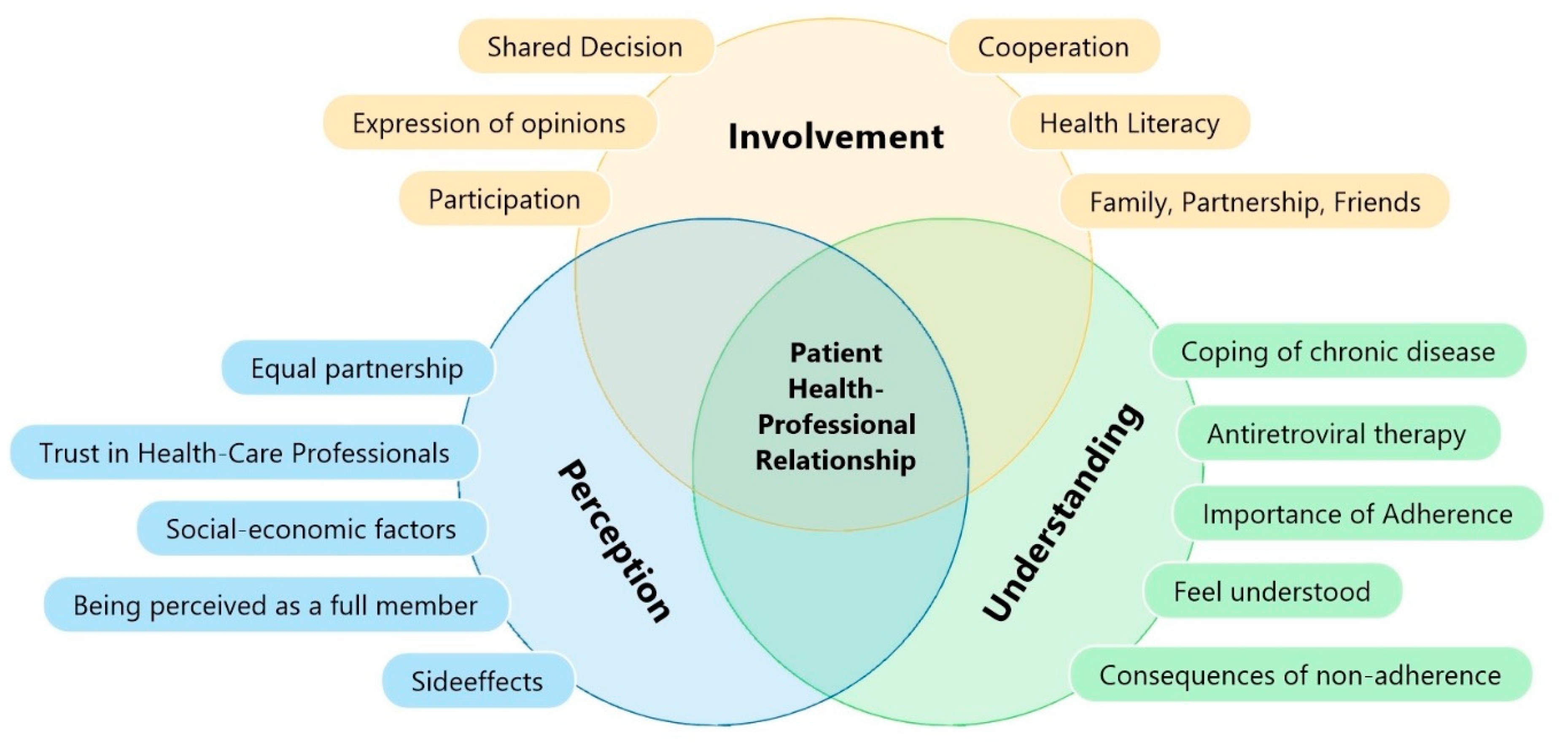

Involvement, Perception, and Understanding as Determinants for Patient–Physician Relationship and Their Association with Adherence: A Questionnaire Survey among People Living with HIV and Antiretroviral Therapy in Austria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Explanatory Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

4. Discussion

Systematic Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Key Considerations

References

- WHO. HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe. Available online: https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/hivaids-surveillance-europe-2018-2017-data (accessed on 27 June 2018).

- ECDC. Available online: https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/documents/HiV-AIDS%20AER_1.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Bundesministerium für Arbeit, Gesundheit und Soziales. Available online: https://www.sozialministerium.at/Themen/Gesundheit/Uebertragbare-Krankheiten/Infektionskrankheiten-A-Z/AIDS---HIV.html (accessed on 24 January 2020).

- Cohen, M.S.; Chen, Y.Q.; McCauley, M.; Gamble, T.; Hosseinipour, M.C.; Kumarasamy, N.; Hakim, J.G.; Kumwenda, J.; Grinsztejn, B.; Pilotto, J.H.; et al. Antiretroviral Therapy for the Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walmsley, S.L.; Thorne, A.; Loutfy, M.R. A prospective randomized controlled trial of structured treatment interruption in HIV-infected patients failing HAART (Canadian HIV Trials Network Study 164). J. AIDS 2003, 45, 418–425. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, J.; Anat, D.S.; Longnecker, N. Doctor-Patient Communication: A Review. Ochsner J. 2010, 10, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, N.; Meintjes, G.; Calmy, A.; Bygrave, H.; Migone, C.; Vitoria, M.; Penazzato, M.; Vojnov, L.; Doherty, M. Managing Advanced HIV Disease in a Public Health Apporach. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 66, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmeyer, H.N.; Hoffmann, K.; Reimann, G.; Stücker, M.; Altmeyer, P.; Brodt, R. Deutsch-Österreichische Richtlinien zur Antiretroviralen Therapie der HIV-Infektion. HIV-Infekt 1999, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, M.C.; Roter, D.L.; Saha, S.; Korthuis, P.T.; Eggly, S.; Cohn, J.; Sharp, V.; Moore, R.D.; Wilson, I.B. Impact of a brief patient and provider intervention to improve the quality of communication about medication adherence among HIV patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wosko, P.; Schnepp, W.; Mayer, H.; Pleschberger, S. Eine Frage des Vertrauens—Grounded Theory-Studie zum Alltagserleben HIV-positiver und an AIDS erkrankter Menschen. Pflege 2020, 34, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flickinger, T.E.; Saha, S.; Moore, R.D.; Beach, M.C. Higher Quality Communication and Relationships Are Associated with Improved Patient Engagement in HIV Care. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2013, 63, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenter, D.; Gillett, J.; Cain, R.; Pawluch, D.; Travers, R. What Do People Living With HIV/AIDS Expect from Their Physicians? Professional Expertise and the Doctor-Patient Relationship. J. Int. Assoc. Physicians AIDS Care 2010, 9, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, B.C.; van Lelyveld, M.A.A.; Vervoort, S.C.J.M.; Lokhorst, A.M.; van Woerkum, C.M.J.; Prins, J.M.; de Bruin, M. Communication Between HIV Patients and Their Providers: A Qualitative Preference Match Analysis. Health Commun. 2014, 31, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.G. The meaning of patient involvement and participation in health care consultations: A taxonomy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 1297–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Williams, S.L.; Haskard, K.B.; DiMatteo, M.R. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2005, 1, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Halabi Oritz, I.; Scholtes, B.; Voz, B.; Gillain, N.; Odero, A.; Baumann, M.; Ziegler, O.; Bragard, I.; Pétré, B. “Patient participation” and related concepts: A scoping review on their dimensional composition. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdat, S.; Hamzehgardeshi, L.; Hessam, S.; Hamzehgardeshi, Z. Patient Involvement in Health Care Decision Making: A Review. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2014, 16, e12454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollo, A.; Golub, S.A.; Wainberg, M.L.; Indyk, D. Patient-Provider Relationship, HIV, and Adherence. Soc. Work Health Care 2008, 42, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbat, I.; Cayless, S.; Knighting, K.; Cornwell, J.; Kearney, N. Engaging patients in health care: An empirical study of the role of engagement on attidudes and action. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, S.M.; Koester, K.A.; Guinness, R.R.; Steward, W.T. Patients’ Perceptions and Experiences of Shared Decision-Making in Primary HIV Care Clinics. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2017, 28, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielscher, C.; Schulte-Sutrum, B. Development of the Physician-patient Relationship in Germany during the Last Years from the Perspective of the Head of Chambers and KVs. In Gesundheitswesen; Georg Thieme: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 78, pp. 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, T.R.; Bradley, E.H.; Towle, V.R.; Allore, H. Understanding the Treatment Preferences of Seriously Ill Patients. New Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.M. Perception: A Concept Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Termin. Classif. 2011, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, L.M.; Stein, M.D.; Savetsky, J.B.; Samet, J.H. The doctor-patient relationship and HIV-infected patients’ satisfaction with primary care physicians. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2000, 15, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengler-Voss, C.; Voss, R. Welche Ansprüche haben meine Patienten an mich und welche Wünsche stecken dahinter? Primary Care 2014, 14, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Brion, J. The Patient–Provider Relationship as Experienced by a Diverse Sample of Highly Adherent HIV-Infected People. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2014, 25, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, L. HIV-Positive Patients and the Doctor-Patient Relationship: Perspectives from the Margins. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterberg, L.; Blasche, T. Adherence to Medication. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, B.J. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy by HIV-infected patients. J. Infect. Dis. 2002, 185 (Suppl. S2), 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd, K.K.; Hou, J.G.; Bush, T.; Hazen, R.; Kirkham, H.; Delpino, A.; Weidle, P.J.; Shankle, M.D.; Camp, N.M.; Suzuki, S.; et al. Adherence and Viral Suppression Among Participants ot the Patient-centered Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Care Model Project: A Collaboration Between Community-based Pharmacists and HIV Clinical Providers. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 789–797. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, A.K.; Celentano, D.D.; Gange, S.J.; Moore, R.D.; Gallant, J.E. Association between adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV drug resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 37, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, L.; Qin, J.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, C. HIV drug resistance and antiretroviral therapy programs in Henan, China-authors’ reply. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 19, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockmeyer, N.H. German-austrian guidelines for diagnostics and treatment. DMW Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 2003, 128, S5–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; Odera, D.N.; Chege, D.; Muigai, E.N.; Patnaik, P.; Michaels-Strasser, S.; Howard, A.A.; Yu-Shears, J.; Dohrn, J. Identifying the Gaps: An Assessment of Nurses’ Training, Competency, and Practice in HIV Care and Treatment in Kenya. J. Asscociation Nurses Aids Care 2016, 27, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenk-Franz, K.; Hunold, G.; Galassi, J.P.; Tiesler, F.; Herrmann, W.; Freund, T.; Steurer-Stey, C.; Djalali, S.; Sönnichsen, A.; Schneider, N.; et al. Quality of the Physician-Patient-Relationship—Evaluation of the German Version of the Patient Reactions Assessment (PRA-D). Dtsch. Ärzte-Verl. ZFA 2016, 92, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kee, J.W.; Khoo, H.S.; Lim, I.; Koh, M.Y. Communication Skills in Patient-Doctor Interactions: Learning from Patient Complaints. Health Prof. Educ. 2018, 4, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridd, M.; Shaw, A.; Lewis, G.; Salisbury, C. The patient–doctor relationship: A synthesis of the qualitative literature on patients’ perspectives. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2009, 59, e116–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Gerver, S.M.; Fidler, S.; Ward, H. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in adolescents with HIV: Systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2014, 28, 1945–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mûnene, E.; Ekman, B. Socioeconomic and clinical factors explaining the risk of unstructured antiretroviral therapy interruptions among Kenyan adult patients. AIDS Care 2016, 28, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Gregson, J.; Parkin, N.; Haile-Selassie, H.; Tanuri, A.; Forero, L.A.; Kaleebu, P.; Watera, C.; Aghokeng, A.; Mutenda, N.; et al. HIV-1 drug resistance before initiation or re-initiation of first-line antiretroviral therapy in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 18, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, K.H.; Venkatesh, K.K. Antiretroviral Therapy as HIV Prevention: Status and Prospects. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1867–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNairy, M.L.; Deryabina, A.; Hoos, D.; El-Sadr, W.M. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of HIV transmission: Potential role for people who inject drugs in Central Asia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013, 132, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.; Rockstroh, J.K. HIV Buch 2018/2019. Available online: https://www.hivbuch.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/HIV2018-19-Komplettversion-als-pdf.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- McNeil, R.; Kerr, T.; Coleman, B.; Maher, L.; Milloy, L.M.; Small, W. Antiretroviral Therapy Interruption Among HIV Positive People Who Use Drugs in a Setting with a Community-Wide HIV Treatment-as-Prevention Initiative. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger-Brand, H. Patientenpartizipation. Informiert entscheiden können. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt. 2012, 109, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Marelich, W.D.; Roberts, K.J.; Murphy, D.A.; Callari, T. HIV/AIDS patient involvement in antiretroviral treatment decisions. AIDS Care 2002, 14, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson-Rose, C.; Cuca, Y.P.; Webel, A.R.; Báez, S.S.S.; Holzemer, W.L.; Rivero-Méndez, M.; Eller, L.S.; Reid, P.; Johnson, M.O.; Kemppainen, J.; et al. Building Trust and Relationships Between Patients and Providers: An Essential Complement to Health Literacy in HIV Care. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2016, 27, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.L.; Shahani, L.; Grimes, R.M.; Hartman, C.; Giordano, T. The Influence of Trust in Physicians and Trust in the Healthcare System on Linkage, Retention, and Adherence to HIV Care. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2015, 29, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarra, A.-M.; Neu, N.; Toussi, S.; Nelson, J.; Larson, E.L. Health Literacy and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Among HIV-Infected Youth. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2014, 25, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elion, R.A. The Physician-Patient Relationship in AIDS Management. AIDS Patient Care 1992, 6, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, V.; Clatworthy, J.; Youssef, E.; Llewellyn, C.; Miners, A.; Lagarde, M.; Sachikonye, M.; Perry, N.; Nixon, E.; Pollard, A.; et al. Which aspects of health care are most valued by people living with HIV in high-income countries? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon, C.; Koosed, T.; Philibert, B.; Raposo, C.; Benzaken, A.S. HIV/AIDS health services in Manaus, Brazil: Patient perception of quality and its influence on adherence to antiretroviral treatment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oetzel, J.; Wilcox, B.; Avila, M.; Hill, R.; Archiopoli, A.; Ginossar, T. Patient–provider interaction, patient satisfaction, and health outcomes: Testing explanatory models for people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2015, 27, 972–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, J.; Kaplan, S.H.; Greenfield, S.; Li, W.; Wilson, I.B. Better Physical-Patient Relationship Are Associated with Higher Reported Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Patients with HIV Infection. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2004, 19, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsega, S. Adult HIV Infection Treatment Update 2014: An Approach to HIV Infection Management and Antiretroviral Treatment. J. Nurse Pract. 2015, 11, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K.J. Physician-Patient Relationships, Patient Satisfaction, and Antiretroviral Medication Adherence Among HIV-Infected Adults Attending a Public Health Clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2002, 16, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acri, T.; Coco, A.; Lin, K.; Johnson, R.; Eckert, P. Knowledge of Structured Treatment Interruption and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2005, 19, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis AMcCrimmon, T.; Dasgupta, A.; Gilbert, L.; Terlikbayeva, A.; Hunt, T.; Primbetova, S.; Wu, E.; Darisheva, M.; El-Bassel, N. Individual, social, and structural factors affecting antiretroviral therapy adherence among HIV-positive people who inject drugs in Kazakhstan. Int. J. Drug Policy 2018, 62, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, S.; Clerc, I.; Bonono, C.-R.; Marcellin, F.; Bilé, P.-C.; Ventelou, B. Non-adherence to antiretroviral treatment and unplanned treatment interruption among people living with HIV/AIDS in Cameroon: Individual and healthcare supply-related factors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langebeek, N.; Gisolf, E.H.; Reiss, P.; Vervoort, S.C.; Hafsteinsdóttir, T.B.; Richter, C.; Sprangers, M.A.; Nieuwkerk, P.T. Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: A meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.-L.; Mo, L.-D.; Su, G.-S.; Huang, J.-P.; Wu, J.-Y.; Su, H.-Z.; Huang, W.-H.; Luo, S.-D.; Ni, Z.-Y. Incidence and types of HIV-1 drug resistance mutation among patients failing first-line antiretroviral therapy. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 139, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, K.; Massey, A.D.; Lopez, A.; Geng, E.H.; Johnson, M.O.; Pilcher, C.; Fielding, H.; Dawson-Rose, C. Taking a Half Day at a Time: Patient Perspectives and the HIV Engagement in Care Continuum. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013, 27, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, J.; Ogden, J. Developing, validating, and consolidating the doctor-patient relationship: The patients’ views of a dynamic process. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 1998, 48, 1391–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, C.; Suzan-Monti, M.; Sagaon-Teyssier, L.; Mimi, M.; Laurent, C.; Maradan, G.; Mengue, M.-T.; Spire, B.; Kuaban, C.; Vidal, L.; et al. Treatment interruption in HIV-positive patients followed up in Cameroon’s antiretroviral treatment programme: Individual and health care supply-related factors (ANRS-12288 EVOLCam survey). Trop. Med. Int. Health 2018, 23, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, C.; Detels, R.; Wu, D. HIV/AIDS patients’ medical and psychosocial needs in the era of HAART: A cross-sectional study among HIV/AIDS patients receiving HAART in Yunnan, China. AIDS Care 2013, 25, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair-Sullivan, N.S.; Mwamba, C.; Whetham, J.; Moore, C.B.; Darking, M.; Vera, J. Barriers to HIV care and adherence for young people living with HIV in Zambia and mHealth. mHealth 2019, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghatol-Eslami, V.C.; Dark, H.E.; Raper, J.L.; Mugavero, M.J.; Turan, J.M.; Turan, B. Brief Report: Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Factors as Parallel Independent Mediators in the Association Between Internalized HIV Stigma and ART Adherence. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2017, 74, e18–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (N = 257) | Adherent (N = 185) | Non-Adherent (N = 72) | p * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding, Mean (SD) | 2.93 | (0.72) | 3.03 | (0.69) | 2.68 | (0.73) | <0.001 |

| Involvement, Mean (SD) | 2.94 | (0.70) | 3.07 | (0.64) | 2.63 | (0.75) | <0.001 |

| Perception, Mean (SD) | 3.24 | (0.69) | 3.24 | (0.61) | 3.00 | (0.81) | 0.002 |

| Length of Therapy, N (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Less than 1 year | 19 | 7.4% | 17 | 9.2% | 2 | 2.8% | |

| 0–3 years | 55 | 21.4% | 51 | 27.6% | 4 | 5.6% | |

| 4–8 years | 80 | 31.1% | 66 | 35.7% | 14 | 19.4% | |

| 9–15 years | 60 | 23.3% | 32 | 17.3% | 28 | 38.9% | |

| Above 15 years | 43 | 16.7% | 19 | 10.3% | 24 | 33.3% | |

| Gender, N (%) | 0.065 | ||||||

| Male | 189 | (73.3%) | 143 | (76.9%) | 46 | (63.9%) | |

| Female | 62 | (24.1%) | 39 | (21.1%) | 23 | (31.9%) | |

| Transgender | 4 | (1.6%) | 2 | (1.1%) | 2 | (2.8%) | |

| Missing | 2 | (0.8%) | 1 | (0.5%) | 1 | (1.4%) | |

| Age, N (%) | 0.003 | ||||||

| ≤34 | 47 | (18.3%) | 42 | (22.6%) | 5 | (6.9%) | |

| 35–49 | 123 | (47.9%) | 89 | (47.8%) | 34 | (47.2%) | |

| 50–65 | 78 | (30.4%) | 47 | (25.3%) | 31 | (43.1%) | |

| ≥66 | 7 | (2.7%) | 6 | (3.2%) | 1 | (1.4%) | |

| Missing | 2 | (0.8%) | 1 | (0.5%) | 1 | (1.4%) | |

| Sexual Orientation, N (%) | 0.147 | ||||||

| Heterosexuell | 98 | (38.1%) | 65 | (35.1%) | 33 | (45.8%) | |

| Homosexuell | 124 | (48.2%) | 96 | (51.9%) | 28 | (38.9%) | |

| Bisexuell | 18 | (7.0%) | 12 | (6.5%) | 6 | (8.3%) | |

| Missing | 17 | (6.6%) | 12 | (6.5%) | 5 | (6.9%) | |

| Education, N (%) | |||||||

| Primary Education | 126 | (49.0%) | 83 | (44.9%) | 43 | (59.7%) | 0.070 |

| Secondary Education | 72 | (28.0%) | 60 | (32.4%) | 12 | (16.7%) | |

| Tertiary Education | 51 | (19.8%) | 39 | (21.1%) | 12 | (16.7%) | |

| Missing | 8 | (3.1%) | 3 | (1.6%) | 5 | (6.9%) | |

| Austrian Regions, N (%) | 0.340 | ||||||

| Burgenland | 2 | (0.8%) | 1 | (0.5%) | 1 | (1.4%) | |

| Kärnten (Carinthia) | 30 | (11.7%) | 19 | (10.3%) | 11 | (15.3%) | |

| Niederösterreich (Lower Austria) | 1 | (0.4%) | 1 | (0.5%) | 0 | (0.0%) | |

| Oberösterreich (Upper Austria) | 11 | (4.3%) | 10 | (5.4%) | 1 | (1.4%) | |

| Salzburg | 32 | (12.5%) | 22 | (12.0%) | 10 | (13.9%) | |

| Steiermark (Styria) | 5 | (2.0%) | 4 | (2.2%) | 1 | (1.4%) | |

| Tirol | 49 | (19.1%) | 32 | (17.4%) | 17 | (23.6%) | |

| Vorarlberg | 6 | (2.3%) | 6 | (3.3%) | 0 | (0.0%) | |

| Wien (Vienna) | 109 | (42.6%) | 83 | (45.1%) | 26 | (36.1%) | |

| Missing | 11 | (4.3%) | 6 | (3.3%) | 5 | (6.9%) | |

| Model | Sub-Model | Variable | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Nagelkerkes R-Quadrat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model I | Understanding | Understanding | 0.51 (0.34–0.75) | 0.001 | 0.065 |

| (N = 256) | |||||

| Involvement | Involvement | 0.42 (0.27–0.63) | <0.001 | 0.102 | |

| (N = 254) | |||||

| Perception | Perception | 0.50 (0.33–0.74) | 0.001 | 0.067 | |

| (N = 253) | |||||

| Model II | Understanding | Understanding | 0.65 (0.37–1.15) | 0.142 | 0.291 |

| (N = 226) | Length of Therapy | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | 0.349 | ||||

| Age | 0.183 | ||||

| Sexual Orientation | 0.943 | ||||

| Education | 0.431 | ||||

| Austrian Region | 0.167 | ||||

| Involvement | Involvement | 0.47 (0.26–0.84) | 0.011 | 0.451 | |

| (N = 225) | Length of Therapy | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | 0.199 | ||||

| Age | 0.178 | ||||

| Sexual Orientation | 0.915 | ||||

| Education | 0.585 | ||||

| Austrian Region | 0.218 | ||||

| Perception | Perception | 0.52 (0.30–0.89) | 0.018 | 0.445 | |

| (N = 224) | Length of Therapy | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | 0.306 | ||||

| Age | 0.148 | ||||

| Sexual Orientation | 0.876 | ||||

| Education | 0.498 | ||||

| Austrian Region | 0.108 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beichler, H.; Grabovac, I.; Leichsenring, B.; Dorner, T.E. Involvement, Perception, and Understanding as Determinants for Patient–Physician Relationship and Their Association with Adherence: A Questionnaire Survey among People Living with HIV and Antiretroviral Therapy in Austria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610314

Beichler H, Grabovac I, Leichsenring B, Dorner TE. Involvement, Perception, and Understanding as Determinants for Patient–Physician Relationship and Their Association with Adherence: A Questionnaire Survey among People Living with HIV and Antiretroviral Therapy in Austria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610314

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeichler, Helmut, Igor Grabovac, Birgit Leichsenring, and Thomas Ernst Dorner. 2022. "Involvement, Perception, and Understanding as Determinants for Patient–Physician Relationship and Their Association with Adherence: A Questionnaire Survey among People Living with HIV and Antiretroviral Therapy in Austria" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610314