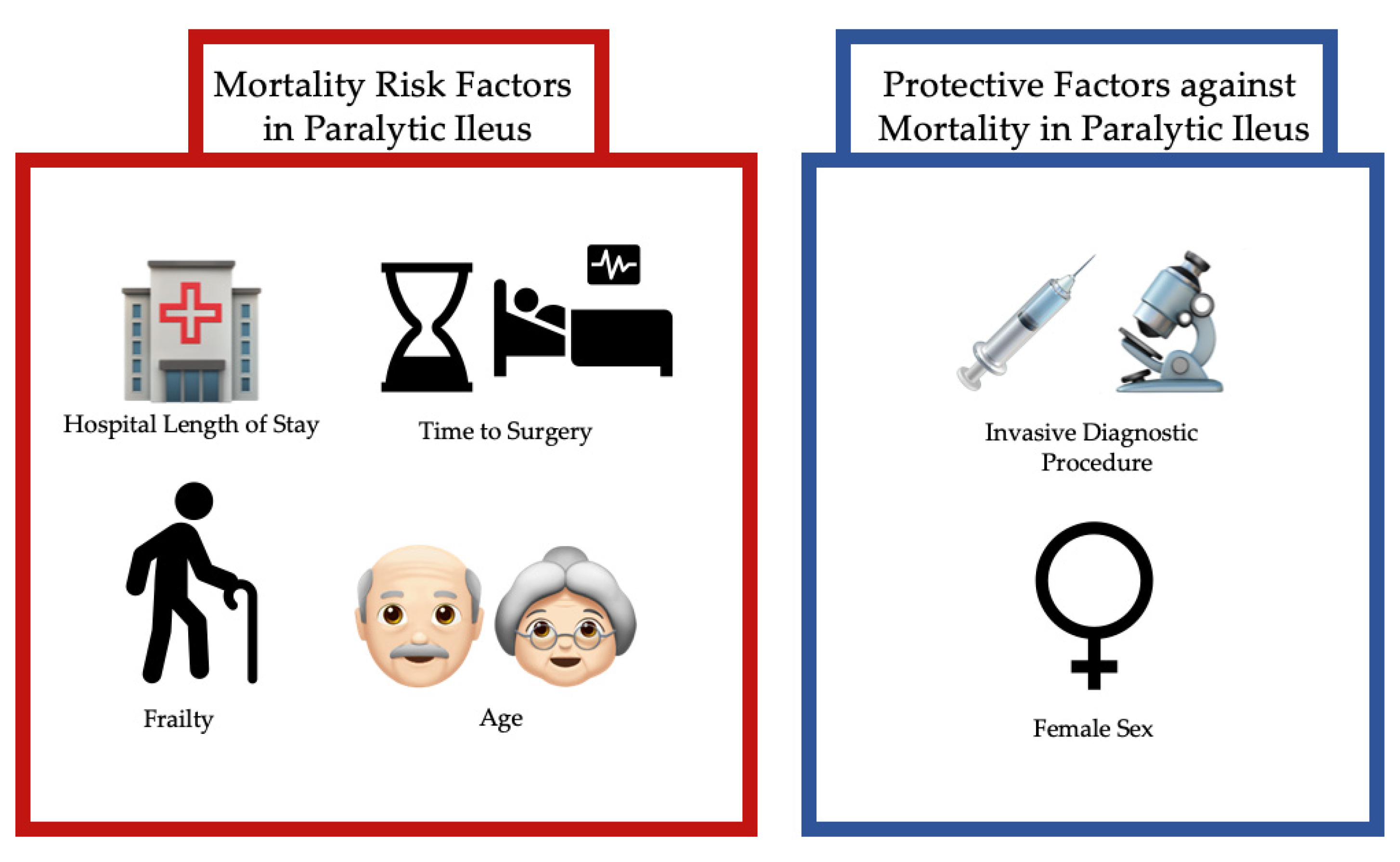

Age Increases the Risk of Mortality by Four-Fold in Patients with Emergent Paralytic Ileus: Hospital Length of Stay, Sex, Frailty, and Time to Operation as Other Risk Factors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

| Digestive Surgical Procedure (ICD 9) | Adults, N (%) | Elderly, N (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedures | Survived | Deceased | p | Procedures | Survived | Deceased | p | |

| Operations on Esophagus (42.01–42.19, 42.31–42.99) | 47 (2.0%) | 46 (97.9%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.270 | 104 (3.6%) | 98 (94.2%) | 6 (5.8%) | 0.100 |

| Operations on Stomach (43.0–44.03, 44.21–44.99) | 235 (10.0%) | 222 (94.5%) | 13 (5.5%) | <0.001 | 392 (13.4%) | 359 (91.6%) | 33 (8.4%) | <0.001 |

| Operations on Intestine (45.00–45.03, 45.30–46.99) | 723 (30.6%) | 698 (96.5%) | 25 (3.5%) | <0.001 | 1312 (44.9%) | 1215 (92.6%) | 97 (7.4%) | <0.001 |

| Operations on Appendix (47.01–47.99) | 124 (5.3%) | 123 (99.2%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0.570 | 41 (1.4%) | 39 (95.1%) | 2 (4.9%) | 0.350 |

| Operations on Rectum, Rectosigmoid and Perirectal Tissue (48.0–48.1, 48.31–48.99) | 60 (2.5%) | 60 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.999 | 97 (3.3%) | 92 (94.8%) | 5 (5.2%) | 0.220 |

| Operations on Anus (49.01–49.12, 49.31–49.99) | 7 (0.3%) | 7 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.999 | 12 (0.4%) | 11 (91.7%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0.310 |

| Operations on Liver (50.0, 50.21–50.99) | 7 (0.3%) | 7 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.999 | 3 (0.1%) | 3 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.999 |

| Operations on Gallbladder and Biliary Tract (51.01–51.04, 51.21–51.99) | 118 (5.0%) | 110 (93.2%) | 8 (6.8%) | <0.001 | 163 (5.6%) | 152 (93.3%) | 11 (6.7%) | 0.006 |

| Operations on Pancreas (52.01–52.09, 52.21–52.99) | 5 (0.2%) | 4 (80.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0.033 | 2 (0.07%) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.999 |

| Operations on Hernia (53.00–53.9) | 62 (2.6%) | 61 (98.4%) | 1 (1.6%) | 0.340 | 72 (2.5%) | 66 (91.7%) | 6 (8.3%) | 0.009 |

| Other Operations on Abdominal Region (54.0–54.19, 54.3–54.99) | 971 (41.2%) | 929 (95.7%) | 42 (4.3%) | <0.001 | 726 (24.8%) | 641 (88.3%) | 85 (11.7%) | <0.001 |

| Digestive Invasive Diagnostic Procedure (ICD 9) | Procedures | Survived | Deceased | p | Procedures | Survived | Deceased | p |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure on Esophagus (42.21–42.29) | 9 (0.2%) | 9 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.999 | 9 (0.2%) | 8 (88.9%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0.240 |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure on Stomach (44.11–44.19) | 12 (0.3%) | 12 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.999 | 18 (0.4%) | 17 (94.4%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0.430 |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure on Intestine (45.11–45.29) | 3397 (88.7%) | 3365 (99.1%) | 32 (0.9%) | 0.048 | 4372 (91.8%) | 4226 (96.7%) | 146 (3.3%) | 0.210 |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure on Rectum, Rectosigmoid and Perirectal Tissue (48.21–48.29) | 136 (3.6%) | 134 (98.5%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0.240 | 158 (3.3%) | 154 (97.5%) | 4 (2.5%) | 0.999 |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure on Anus (49.21–49.29) | 6 (0.2%) | 6 (100%) | 0 0(%) | 0.999 | 5 (0.1%) | 5 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.999 |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure on Liver (50.11–50.19) | 43 (1.1%) | 42 (97.7%) | 1 (2.3%) | 0.250 | 36 (0.8%) | 34 (94.4%) | 2 (5.6%) | 0.300 |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure on Gallbladder and Biliary Tract (51.10–51.19) | 21 (0.5%) | 20 (95.2%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0.130 | 23 (0.5%) | 22 (95.7%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.510 |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure on Pancreas (52.11–52.19) | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.999 | 5 (0.1%) | 4 (80.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0.140 |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure on Other Operations on Abdominal Region (54.21–54.29) | 204 (5.3%) | 201 (98.5%) | 3 (1.5%) | 0.160 | 135 (2.8%) | 126 (93.3%) | 9 (6.7%) | 0.014 |

3. Results

3.1. Surgical and Invasive Diagnostic Procedures

3.2. Gender Differences

| Adult, N (%) | Elderly, N (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | p | Male | Female | p | ||

| All Cases | 17,702 (48.0%) | 19,214 (52.0%) | 19,740 (44.1%) | 25,018 (55.9%) | |||

| Race | White | 10,485 (70.0%) | 11,357 (70.7%) | 0.002 | 13,082 (79.1%) | 16,717 (80.3%) | 0.002 |

| Black | 2493 (16.6%) | 2708 (16.9%) | 1758 (10.6%) | 2053 (9.9%) | |||

| Hispanic | 1302 (8.7%) | 1348 (8.4%) | 987 (6.0%) | 1267 (6.1%) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 245 (1.6%) | 243 (1.5%) | 309 (1.9%) | 314 (1.5%) | |||

| Native American | 102 (0.7%) | 120 (0.7%) | 91 (0.6%) | 127 (0.6%) | |||

| Other | 357 (2.4%) | 278 (1.7%) | 309 (1.9%) | 330 (1.6%) | |||

| Income Quartile | Quartile 1 | 5514 (32.1%) | 5924 (31.5%) | 0.580 | 5852 (30.3%) | 7595 (30.9%) | 0.320 |

| Quartile 2 | 4801 (27.9%) | 5242 (27.9%) | 5527 (28.6%) | 6882 (28.0%) | |||

| Quartile 3 | 3953 (23.0%) | 4392 (23.3%) | 4497 (23.3%) | 5771 (23.5%) | |||

| Quartile 4 | 2927 (17.0%) | 3262 (17.3%) | 3462 (17.9%) | 4328 (17.6%) | |||

| Insurance | Private Insurance | 7002 (39.7%) | 8254 (43.1%) | <0.001 | 1394 (7.1%) | 1310 (5.2%) | <0.001 |

| Medicare | 5233 (29.6%) | 4860 (25.4%) | 17,819 (90.4%) | 23,141 (92.6%) | |||

| Medicaid | 3136 (17.8%) | 4147 (21.6%) | 196 (1.0%) | 330 (1.3%) | |||

| Self-Pay | 1412 (8.0%) | 1208 (6.3%) | 67 (0.3%) | 62 (0.2%) | |||

| No Charge | 137 (0.8%) | 106 (0.6%) | 7 (0.0%) | 9 (0.0%) | |||

| Other | 730 (4.1%) | 589 (3.1%) | 223 (1.1%) | 138 (0.6%) | |||

| Hospital Location | Rural | 3015 (17.0%) | 3381 (17.6%) | 0.360 | 4270 (21.6%) | 5368 (21.5%) | 0.015 |

| Urban: Non-Teaching | 7862 (44.4%) | 8480 (44.1%) | 9026 (45.7%) | 11,762 (47.0%) | |||

| Urban: Teaching | 6825 (38.6%) | 7353 (38.3%) | 6444 (32.6%) | 7888 (31.5%) | |||

| Comorbidities | AIDS | 159 (0.9%) | 51 (0.3%) | <0.001 | 14 (0.1%) | 2 (0.0%) | 0.001 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 1050 (5.9%) | 384 (2.0%) | <0.001 | 402 (2.0%) | 137 (0.5%) | <0.001 | |

| Deficiency Anemias | 2215 (12.5%) | 3356 (17.5%) | <0.001 | 3967 (20.1%) | 5392 (21.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 200 (1.1%) | 821 (4.3%) | <0.001 | 336 (1.7%) | 1128 (4.5%) | <0.001 | |

| Chronic Blood Loss | 74 (0.4%) | 120 (0.6%) | 0.006 | 164 (0.8%) | 216 (0.9%) | 0.710 | |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 708 (4.0%) | 656 (3.4%) | 0.003 | 3190 (16.2%) | 4169 (16.7%) | 0.150 | |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 2439 (13.8%) | 3456 (18.0%) | <0.001 | 4992 (25.3%) | 5929 (23.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Coagulopathy | 596 (3.4%) | 479 (2.5%) | <0.001 | 821 (4.2%) | 631 (2.5%) | <0.001 | |

| Depression | 1799 (10.2%) | 3442 (17.9%) | <0.001 | 1605 (8.1%) | 3200 (12.8%) | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes, Uncomplicated | 2768 (15.6%) | 2644 (13.8%) | <0.001 | 4593 (23.3%) | 5173 (20.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes, Chronic Complications | 615 (3.5%) | 629 (3.3%) | 0.290 | 838 (4.2%) | 905 (3.6%) | 0.001 | |

| Drug Abuse | 1096 (6.2%) | 1133 (5.9%) | 0.240 | 155 (0.8%) | 254 (1.0%) | 0.011 | |

| Hypertension | 7155 (40.4%) | 6514 (33.9%) | <0.001 | 12,524 (63.4%) | 16,723 (66.8%) | <0.001 | |

| Hypothyroidism | 918 (5.2%) | 2380 (12.4%) | <0.001 | 2038 (10.3%) | 5497 (22.0%) | <0.001 | |

| Liver Disease | 1194 (6.7%) | 854 (4.4%) | <0.001 | 464 (2.4%) | 414 (1.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Lymphoma | 157 (0.9%) | 129 (0.7%) | 0.018 | 349 (1.8%) | 308 (1.2%) | <0.001 | |

| Fluid/Electrolyte Disorders | 6519 (36.8%) | 7604 (39.6%) | <0.001 | 9000 (45.6%) | 12,787 (51.1%) | <0.001 | |

| Metastatic Cancer | 870 (4.9%) | 1130 (5.9%) | <0.001 | 1176 (6.0%) | 1177 (4.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Other Neurological Disorders | 2177 (12.3%) | 2011 (10.5%) | <0.001 | 2610 (13.2%) | 2918 (11.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Obesity | 1344 (7.6%) | 1838 (9.6%) | <0.001 | 1003 (5.1%) | 1471 (5.9%) | <0.001 | |

| Paralysis | 1876 (10.6%) | 988 (5.1%) | <0.001 | 1036 (5.2%) | 739 (3.0%) | <0.001 | |

| Peripheral Vascular Disorders | 458 (2.6%) | 347 (1.8%) | <0.001 | 2052 (10.4%) | 1768 (7.1%) | <0.001 | |

| Psychoses | 1333 (7.5%) | 1615 (8.4%) | 0.002 | 619 (3.1%) | 974 (3.9%) | <0.001 | |

| Pulmonary Circulation Disorders | 132 (0.7%) | 187 (1.0%) | 0.018 | 361 (1.8%) | 544 (2.2%) | 0.010 | |

| Renal Failure | 1259 (7.1%) | 969 (5.0%) | <0.001 | 3288 (16.7%) | 2762 (11.0%) | <0.001 | |

| Solid Tumor | 513 (2.9%) | 639 (3.3%) | 0.018 | 1050 (5.3%) | 932 (3.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Peptic Ulcer | 11 (0.1%) | 14 (0.1%) | 0.690 | 11 (0.1%) | 21 (0.1%) | 0.270 | |

| Valvular Disease | 243 (1.4%) | 363 (1.9%) | <0.001 | 1036 (5.2%) | 1415 (5.7%) | 0.060 | |

| Weight Loss | 1044 (5.9%) | 1193 (6.2%) | 0.210 | 1629 (8.3%) | 2242 (9.0%) | 0.008 | |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure | 1689 (9.5%) | 2017 (10.5%) | 0.002 | 2238 (11.3%) | 2390 (9.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Surgical Procedure | 1079 (6.1%) | 922 (4.8%) | <0.001 | 1341 (6.8%) | 1205 (4.8%) | <0.001 | |

| Invasive or Surgical Procedure | 2476 (14.0%) | 2690 (14.0%) | 0.970 | 3122 (15.8%) | 3182 (12.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Deceased | 146 (0.8%) | 104 (0.5%) | 0.001 | 615 (3.1%) | 741 (3.0%) | 0.350 | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | ||

| Age, Years | 48.63 (11.65) | 48.04 (11.40) | <0.001 | 77.65 (7.81) | 79.67 (8.22) | <0.001 | |

| Modified Frailty Index | 1.08 (1.02) | 0.97 (1.01) | <0.001 | 1.71 (1.10) | 1.61 (1.06) | <0.001 | |

| Time to Invasive Diagnostic Procedure, Days | 3.40 (3.55) | 3.41 (3.23) | 0.970 | 3.61 (3.68) | 3.96 (4.11) | 0.005 | |

| Time to Surgical Procedure, Days | 3.95 (6.54) | 4.00 (4.98) | 0.860 | 4.45 (4.73) | 5.06 (5.53) | 0.005 | |

| Hospital Length of Stay, Days | 4.41 (5.87) | 4.35 (4.57) | 0.300 | 5.29 (5.28) | 5.24 (4.84) | 0.290 | |

| Total Charges, Dollars | 24,219 (41,680) | 23,302 (35,865) | 0.025 | 27,458 (38,898) | 25,849 (35,863) | <0.001 | |

3.3. Mortality

| Adult, N (%) | Elderly, N (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survived | Deceased | p | Survived | Deceased | p | ||

| All Cases | 36,661 (99.3%) | 250 (0.7%) | 43,388 (97.0%) | 1356 (3.0%) | |||

| Sex, Female | 19,097 (52.1%) | 104 (41.6%) | 0.001 | 24,265 (55.9%) | 741 (54.6%) | 0.350 | |

| Race | White | 21,683 (70.4%) | 136 (67.0%) | 0.110 | 28,864 (79.7%) | 922 (82.2%) | 0.006 |

| Black | 5160 (16.7%) | 39 (19.2%) | 3691 (10.2%) | 120 (10.7%) | |||

| Hispanic | 2636 (8.6%) | 13 (6.4%) | 2212 (6.1%) | 40 (3.6%) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 483 (1.6%) | 5 (2.5%) | 609 (1.7%) | 14 (1.2%) | |||

| Native American | 221 (0.7%) | 1 (0.5%) | 215 (0.6%) | 3 (0.3%) | |||

| Other | 626 (2.0%) | 9 (4.4%) | 617 (1.7%) | 22 (2.0%) | |||

| Income Quartile | Quartile 1 | 11,350 (31.7%) | 85 (35.1%) | 0.500 | 13,022 (30.6%) | 424 (32.1%) | 0.600 |

| Quartile 2 | 9978 (27.9%) | 63 (26.0%) | 12,043 (28.3%) | 359 (27.2%) | |||

| Quartile 3 | 8296 (23.2%) | 49 (20.2%) | 9963 (23.4%) | 299 (22.7%) | |||

| Quartile 4 | 6143 (17.2%) | 45 (18.6%) | 7552 (17.7%) | 238 (18.0%) | |||

| Insurance | Private Insurance | 15,182 (41.5%) | 78 (31.2%) | 0.002 | 2628 (6.1%) | 77 (5.7%) | 0.180 |

| Medicare | 9990 (27.3%) | 95 (38.0%) | 39,715 (91.7%) | 1231 (91.1%) | |||

| Medicaid | 7228 (19.8%) | 54 (21.6%) | 506 (1.2%) | 19 (1.4%) | |||

| Self-Pay | 2607 (7.1%) | 12 (4.8%) | 122 (0.3%) | 7 (0.5%) | |||

| No Charge | 241 (0.7%) | 2 (0.8%) | 15 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) | |||

| Other | 1311 (3.6%) | 9 (3.6%) | 344 (0.8%) | 17 (1.3%) | |||

| Hospital Location | Rural | 6358 (17.3%) | 35 (14.0%) | 0.054 | 9366 (21.6%) | 269 (19.8%) | 0.054 |

| Urban: Non-Teaching | 16,238 (44.3%) | 101 (40.4%) | 20,168 (46.5%) | 614 (45.3%) | |||

| Urban: Teaching | 14,065 (38.4%) | 114 (45.6%) | 13,854 (31.9%) | 473 (34.9%) | |||

| Comorbidities | AIDS | 206 (0.6%) | 4 (1.6%) | 0.060 | 16 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.999 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 1419 (3.9%) | 14 (5.6%) | 0.160 | 520 (1.2%) | 19 (1.4%) | 0.500 | |

| Deficiency Anemias | 5502 (15.0%) | 66 (26.4%) | <0.001 | 9078 (20.9%) | 278 (20.5%) | 0.710 | |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 1013 (2.8%) | 6 (2.4%) | 0.730 | 1427 (3.3%) | 36 (2.7%) | 0.200 | |

| Chronic Blood Loss | 188 (0.5%) | 5 (2.0%) | 0.001 | 360 (0.8%) | 19 (1.4%) | 0.024 | |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 1319 (3.6%) | 45 (18.0%) | <0.001 | 6908 (15.9%) | 445 (32.8%) | <0.001 | |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 5850 (16.0%) | 43 (17.2%) | 0.590 | 10,503 (24.2%) | 413 (30.5%) | <0.001 | |

| Coagulopathy | 1040 (2.8%) | 35 (14.0%) | <0.001 | 1352 (3.1%) | 100 (7.4%) | <0.001 | |

| Depression | 5205 (14.2%) | 30 (12.0%) | 0.320 | 4707 (10.8%) | 97 (7.2%) | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes, Uncomplicated | 5372 (14.7%) | 38 (15.2%) | 0.810 | 9516 (21.9%) | 245 (18.1%) | 0.001 | |

| Diabetes, Chronic Complications | 1234 (3.4%) | 9 (3.6%) | 0.840 | 1682 (3.9%) | 61 (4.5%) | 0.240 | |

| Drug Abuse | 2216 (6.0%) | 11 (4.4%) | 0.280 | 400 (0.9%) | 8 (0.6%) | 0.210 | |

| Hypertension | 13,567 (37.0%) | 99 (39.6%) | 0.400 | 28,468 (65.6%) | 769 (56.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Hypothyroidism | 3275 (8.9%) | 22 (8.8%) | 0.940 | 7340 (16.9%) | 192 (14.2%) | 0.008 | |

| Liver Disease | 2010 (5.5%) | 36 (14.4%) | <0.001 | 839 (1.9%) | 39 (2.9%) | 0.014 | |

| Lymphoma | 284 (0.8%) | 2 (0.8%) | 0.720 | 626 (1.4%) | 31 (2.3%) | 0.011 | |

| Fluid/Electrolyte Disorders | 13,955 (38.1%) | 157 (62.8%) | <0.001 | 20,931 (48.2%) | 845 (62.3%) | <0.001 | |

| Metastatic Cancer | 1918 (5.2%) | 80 (32.0%) | <0.001 | 2213 (5.1%) | 140 (10.3%) | <0.001 | |

| Other Neurological Disorders | 4143 (11.3%) | 37 (14.8%) | 0.080 | 5315 (12.2%) | 209 (15.4%) | <0.001 | |

| Obesity | 3165 (8.6%) | 12 (4.8%) | 0.031 | 2420 (5.6%) | 51 (3.8%) | 0.004 | |

| Paralysis | 2831 (7.7%) | 31 (12.4%) | 0.006 | 1715 (4.0%) | 58 (4.3%) | 0.550 | |

| Peripheral Vascular Disorders | 791 (2.2%) | 14 (5.6%) | <0.001 | 3654 (8.4%) | 164 (12.1%) | <0.001 | |

| Psychoses | 2931 (8.0%) | 15 (6.0%) | 0.250 | 1555 (3.6%) | 39 (2.9%) | 0.170 | |

| Pulmonary Circulation Disorders | 305 (0.8%) | 14 (5.6%) | <0.001 | 847 (2.0%) | 57 (4.2%) | <0.001 | |

| Renal Failure | 2180 (5.9%) | 46 (18.4%) | <0.001 | 5727 (13.2%) | 319 (23.5%) | <0.001 | |

| Solid Tumor | 1143 (3.1%) | 9 (3.6%) | 0.660 | 1908 (4.4%) | 73 (5.4%) | 0.080 | |

| Peptic Ulcer | 25 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.999 | 30 (0.1%) | 2 (0.1%) | 0.250 | |

| Valvular Disease | 599 (1.6%) | 7 (2.8%) | 0.150 | 2358 (5.4%) | 91 (6.7%) | 0.042 | |

| Weight Loss | 2165 (5.9%) | 71 (28.4%) | <0.001 | 3593 (8.3%) | 275 (20.3%) | <0.001 | |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure | 3667 (10.0%) | 37 (14.8%) | 0.012 | 4469 (10.3%) | 158 (11.7%) | 0.110 | |

| Surgical Procedure | 1929 (5.3%) | 70 (28.0%) | <0.001 | 2355 (5.4%) | 189 (13.9%) | <0.001 | |

| Invasive or Surgical Procedure | 5074 (13.8%) | 88 (35.2%) | <0.001 | 6011 (13.9%) | 290 (21.4%) | <0.001 | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | ||

| Age, Years | 48.28 (11.53) | 53.98 (9.03) | <0.001 | 78.70 (8.09) | 81.54 (8.10) | <0.001 | |

| Modified Frailty Index | 1.02 (1.01) | 1.70 (1.03) | <0.001 | 1.64 (1.07) | 1.96 (1.17) | <0.001 | |

| Time to Invasive Diagnostic Procedure, Days | 3.36 (3.28) | 8.80 (7.55) | <0.001 | 3.68 (3.63) | 6.82 (8.25) | <0.001 | |

| Time to Surgical Procedure, Days | 3.88 (5.73) | 6.83 (8.43) | 0.010 | 4.66 (5.05) | 5.73 (5.96) | 0.023 | |

| Hospital Length of Stay, Days | 4.32 (5.00) | 12.48 (17.91) | <0.001 | 5.17 (4.80) | 8.08 (9.71) | <0.001 | |

| Total Charges, Dollars | 23,230 (36,190) | 99,500 (157,102) | <0.001 | 25,632 (33,260) | 56,101 (97,159) | <0.001 | |

3.4. Operation vs. No Operation

| Adult, N (%) | Elderly, N (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Operation | Operation | p | No Operation | Operation | p | ||

| All Cases | 34,939 (94.6%) | 2001 (5.4%) | 42,217 (94.3%) | 2546 (5.7%) | |||

| Sex, Female | 18,292 (52.4%) | 922 (46.1%) | <0.001 | 23,813 (56.4%) | 1205 (47.3%) | <0.001 | |

| Race | White | 20,629 (70.3%) | 1213 (71.4%) | 0.380 | 28,067 (79.9%) | 1732 (78.4%) | 0.007 |

| Black | 4911 (16.7%) | 290 (17.1%) | 3538 (10.1%) | 273 (12.4%) | |||

| Hispanic | 2520 (8.6%) | 130 (7.6%) | 2122 (6.0%) | 132 (6.0%) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 462 (1.6%) | 26 (1.5%) | 589 (1.7%) | 34 (1.5%) | |||

| Native American | 216 (0.7%) | 6 (0.4%) | 212 (0.6%) | 6 (0.3%) | |||

| Other | 600 (2.0%) | 35 (2.1%) | 606 (1.7%) | 33 (1.5%) | |||

| Income Quartile | Quartile 1 | 10,859 (31.8%) | 583 (30.1%) | 0.440 | 12,719 (30.7%) | 729 (29.2%) | 0.170 |

| Quartile 2 | 9491 (27.8%) | 555 (28.7%) | 11,709 (28.3%) | 701 (28.1%) | |||

| Quartile 3 | 7896 (23.2%) | 454 (23.4%) | 9642 (23.3%) | 626 (25.1%) | |||

| Quartile 4 | 5853 (17.2%) | 345 (17.8%) | 7350 (17.7%) | 443 (17.7%) | |||

| Insurance | Private Insurance | 14,488 (41.6%) | 784 (39.3%) | 0.045 | 2543 (6.0%) | 162 (6.4%) | 0.890 |

| Medicare | 9496 (27.3%) | 599 (30.0%) | 38,638 (91.7%) | 2326 (91.4%) | |||

| Medicaid | 6875 (19.7%) | 410 (20.6%) | 495 (1.2%) | 31 (1.2%) | |||

| Self-Pay | 2497 (7.2%) | 124 (6.2%) | 123 (0.3%) | 6 (0.2%) | |||

| No Charge | 230 (0.7%) | 13 (0.7%) | 16 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Other | 1257 (3.6%) | 65 (3.3%) | 340 (0.8%) | 21 (0.8%) | |||

| Hospital Location | Rural | 6171 (17.7%) | 225 (11.2%) | <0.001 | 9268 (22.0%) | 370 (14.5%) | <0.001 |

| Urban: Non-Teaching | 15,529 (44.4%) | 829 (41.4%) | 19,856 (46.4%) | 1206 (47.4%) | |||

| Urban: Teaching | 13,239 (37.9%) | 947 (47.3%) | 13,363 (31.7%) | 970 (38.1%) | |||

| Comorbidities | AIDS | 195 (0.6%) | 15 (0.7%) | 0.270 | 13 (0.0%) | 3 (0.1%) | 0.060 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 1305 (3.7%) | 129 (6.4%) | <0.001 | 490 (1.2%) | 49 (1.9%) | <0.001 | |

| Deficiency Anemias | 5119 (14.7%) | 452 (22.6%) | <0.001 | 8667 (20.5%) | 692 (27.2%) | <0.001 | |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 958 (2.7%) | 63 (3.1%) | 0.280 | 1399 (3.3%) | 65 (2.6%) | 0.036 | |

| Chronic Blood Loss | 170 (0.5%) | 24 (1.2%) | <0.001 | 326 (0.8%) | 54 (2.1%) | <0.001 | |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 1256 (3.6%) | 108 (5.4%) | <0.001 | 6872 (16.3%) | 487 (19.1%) | <0.001 | |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 5572 (15.9%) | 323 (16.1%) | 0.820 | 10,295 (24.4%) | 626 (24.6%) | 0.820 | |

| Coagulopathy | 932 (2.7%) | 143 (7.1%) | <0.001 | 1304 (3.1%) | 148 (5.8%) | <0.001 | |

| Depression | 4974 (14.2%) | 267 (13.3%) | 0.270 | 4527 (10.7%) | 278 (10.9%) | 0.760 | |

| Diabetes, Uncomplicated | 5089 (14.6%) | 323 (16.1%) | 0.052 | 9190 (21.8%) | 576 (22.6%) | 0.310 | |

| Diabetes, Chronic Complications | 1173 (3.4%) | 71 (3.5%) | 0.650 | 1611 (3.8%) | 132 (5.2%) | <0.001 | |

| Drug Abuse | 2124 (6.1%) | 105 (5.2%) | 0.130 | 387 (0.9%) | 22 (0.9%) | 0.790 | |

| Hypertension | 12,881 (36.9%) | 790 (39.5%) | 0.019 | 27,646 (65.5%) | 1602 (62.9%) | 0.008 | |

| Hypothyroidism | 3137 (9.0%) | 162 (8.1%) | 0.180 | 7152 (16.9%) | 383 (15.0%) | 0.013 | |

| Liver Disease | 1774 (5.1%) | 274 (13.7%) | <0.001 | 730 (1.7%) | 148 (5.8%) | <0.001 | |

| Lymphoma | 268 (0.8%) | 18 (0.9%) | 0.510 | 634 (1.5%) | 23 (0.9%) | 0.015 | |

| Fluid/Electrolyte Disorders | 13,211 (37.8%) | 913 (45.6%) | <0.001 | 20,313 (48.1%) | 1474 (57.9%) | <0.001 | |

| Metastatic Cancer | 1790 (5.1%) | 210 (10.5%) | <0.001 | 2131 (5.0%) | 222 (8.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Other Neurological Disorders | 3927 (11.2%) | 261 (13.0%) | 0.013 | 5203 (12.3%) | 325 (12.8%) | 0.510 | |

| Obesity | 3010 (8.6%) | 172 (8.6%) | 0.980 | 2289 (5.4%) | 185 (7.3%) | <0.001 | |

| Paralysis | 2678 (7.7%) | 187 (9.3%) | 0.006 | 1635 (3.9%) | 140 (5.5%) | <0.001 | |

| Peripheral Vascular Disorders | 750 (2.1%) | 55 (2.7%) | 0.070 | 3575 (8.5%) | 245 (9.6%) | 0.043 | |

| Psychoses | 2797 (8.0%) | 152 (7.6%) | 0.510 | 1511 (3.6%) | 83 (3.3%) | 0.400 | |

| Pulmonary Circulation Disorders | 289 (0.8%) | 30 (1.5%) | 0.002 | 832 (2.0%) | 73 (2.9%) | 0.002 | |

| Renal Failure | 2018 (5.8%) | 210 (10.5%) | <0.001 | 5610 (13.3%) | 440 (17.3%) | <0.001 | |

| Solid Tumor | 1061 (3.0%) | 91 (4.5%) | <0.001 | 1841 (4.4%) | 141 (5.5%) | 0.005 | |

| Peptic Ulcer | 24 (0.1%) | 1 (0.0%) | 0.999 | 28 (0.1%) | 4 (0.2%) | 0.110 | |

| Valvular Disease | 564 (1.6%) | 42 (2.1%) | 0.100 | 2282 (5.4%) | 169 (6.6%) | 0.008 | |

| Weight Loss | 1875 (5.4%) | 362 (18.1%) | <0.001 | 3306 (7.8%) | 565 (22.2%) | <0.001 | |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure | 3166 (9.1%) | 541 (27.0%) | <0.001 | 3758 (8.9%) | 870 (34.2%) | <0.001 | |

| Deceased | 180 (0.5%) | 70 (3.5%) | <0.001 | 1167 (2.8%) | 189 (7.4%) | <0.001 | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | ||

| Age, Years | 48.19 (11.56) | 50.56 (10.68) | <0.001 | 78.84 (8.13) | 77.83 (7.63) | <0.001 | |

| Modified Frailty Index | 1.01 (1.01) | 1.27 (1.04) | <0.001 | 1.64 (1.08) | 1.85 (1.12) | <0.001 | |

| Time to Invasive Diagnostic Procedure, Days | 3.22 (3.13) | 4.56 (4.50) | <0.001 | 3.52 (3.43) | 4.96 (5.43) | <0.001 | |

| Hospital Length of Stay, Days | 4.01 (3.96) | 10.71 (13.78) | <0.001 | 4.88 (4.24) | 11.57 (10.31) | <0.001 | |

| Total Charges, Dollars | 21,111 (26,716) | 69,609 (114,254) | <0.001 | 24,029 (30,451) | 68,622 (84,591) | <0.001 | |

3.5. Risk Factors of Mortality

| Adult Operation | Elderly Operation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1730 | R2 = 0.073 | n = 2230 | R2 = 0.013 | |

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Time to Operation, Days | 1.041 (1.015, 1.068) | 0.002 | 1.032 (1.006, 1.059) | 0.014 |

| Age, Years | 1.038 (1.005, 1.073) | 0.026 | 1.026 (1.005, 1.047) | 0.015 |

| Modified Frailty Index | 1.529 (1.207, 1.936) | <0.001 | Removed Via Backward Elimination | |

| Sex, Female | Removed Via Backward Elimination | |||

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure | ||||

| Race | ||||

| Income Quartile | ||||

| Insurance | ||||

| Hospital Location | ||||

| Adult Non-Operation | Elderly Non-Operation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 34,888 | R2 = 0.068 | n = 42,200 | R2 = 0.041 | |

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Hospital Length of Stay, Days | 1.076 (1.059, 1.094) | <0.001 | 1.058 (1.049, 1.068) | <0.001 |

| Age, Years | 1.040 (1.023, 1.058) | <0.001 | 1.050 (1.042, 1.057) | <0.001 |

| Modified Frailty Index | 1.392 (1.220, 1.590) | <0.001 | 1.261 (1.197, 1.330) | <0.001 |

| Sex, Female | 0.716 (0.531, 0.965) | 0.028 | Removed | |

| Invasive Diagnostic Procedure | Removed Via Backward Elimination | 0.784 (0.633, 0.971) | 0.026 | |

| Race | Removed Via Backward Elimination | |||

| Income Quartile | ||||

| Insurance | ||||

| Hospital Location | ||||

| Subramaniam 5-Item MFI Factors | NIS Variable for Our Modified 5-Item mFI Estimate |

|---|---|

| Functional Health Status (Partially or Totally) | Presence of at Least 1: Solid Tumor, Renal Failure, Metastatic Cancer, Paralysis, Lymphoma, Coagulopathy, Weight Loss |

| Diabetes Mellitus (Non/Insulin) | Diabetes (Uncomplicated) or Diabetes (Chronic Complications) |

| History of COPD | Chronic Pulmonary Disease |

| History of Congestive Heart Failure | Congestive Heart Failure |

| Hypertension Requiring Medication | Hypertension (Un/Complicated) |

4. Discussion

4.1. Age and Mortality

4.2. Hospital Length of Stay and Mortality

4.3. Modified Frailty Index and Mortality

4.4. Time to Operation and Mortality

4.5. Sex and Mortality

4.6. Invasive Diagnostic Procedure and Mortality

4.7. Strengths

4.8. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bederman, S.; Betsy, M.; Winiarsky, R.; Seldes, R.M.; Sharrock, N.E.; Sculco, T.P. Postoperative Ileus in the Lower Extremity Arthroplasty Patient. J. Arthroplast. 2001, 16, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, N.P.; Schneider, R.; Wehner, S.; Kalff, J.C.; Vilz, T.O. State-of-the-Art Colorectal Disease: Postoperative Ileus. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 2017–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Li, W.; Yan, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, M.; Luo, Z.; Xie, L.; Ma, Y.; Xu, X.; et al. Transcutaneous Electrical Acupoint Stimulation Applied in Lower Limbs Decreases the Incidence of Paralytic Ileus after Colorectal Surgery: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Surgery 2021, 170, 1618–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgeirsson, T.; El-Badawi, K.I.; Mahmood, A.; Barletta, J.; Luchtefeld, M.; Senagore, A.J. Postoperative Ileus: It Costs More than You Expect. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2010, 210, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weledji, E.P. Perspectives on Paralytic Ileus. Acute Med. Surg. 2020, 7, e573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senagore, A.J. Pathogenesis and Clinical and Economic Consequences of Postoperative Ileus. Am. J. Health Pharm. 2007, 64 (Suppl. S13), S3–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koşar, M.N.; Görgülü, Ö. Incidence and Mortality Results of Intestinal Obstruction in Geriatric and Adult Patients: 10 Years Retrospective Analysis. Turk. J. Surg. 2021, 37, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunrinde, T.J.; Dosumu, O.; Shaba, O.P.; Akeredolu, P.A.; Ajayi, M.D. The Influence of the Design of Mandibular Major Connectors on Gingival Health. Afr. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2014, 43, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bragg, D.; El-Sharkawy, A.M.; Psaltis, E.; Maxwell-Armstrong, C.A.; Lobo, D.N. Postoperative Ileus: Recent Developments in Pathophysiology and Management. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saclarides, T.J. Current Choices—Good or Bad—For the Proactive Management of Postoperative Ileus: A Surgeon’s View. J. PeriAnesthesia Nurs. 2006, 21, S7–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapan, M.; Onder, A.; Polat, S.; Aliosmanoglu, I.; Arikanoglu, Z.; Taskesen, F.; Girgin, S. Mechanical Bowel Obstruction and Related Risk Factors on Morbidity and Mortality. J. Curr. Surg. 2012, 2, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, N.G.; Sharma, D. Comparative Study of Large and Small Intestinal Obstruction. Int. J. Pharm. Med. Res. 2015, 3, 5–9. Available online: https://www.woarjournals.org/admin/vol_issue2/upload%20Image/IJPMR031102.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Arenal, J.; Concejo, M.P.; Benito, C.; Sánchez, J.; García-Abril, J.M.; Ortega, E. Intestinal Obstruction in the Elderly. Prognostic Factors of Mortality. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. Organo Of. Soc. Esp. Patol. Dig. 1999, 91, 838–845. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, C.; Minnema, A.J.; Baum, J.; Humeidan, M.L.; Vazquez, D.E.; Farhadi, H.F. Development of a Postoperative Ileus Risk Assessment Scale: Identification of Intraoperative Opioid Exposure as a Significant Predictor after Spinal Surgery. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2019, 31, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, A.L.; Kelly, Y.M.; McKay, R.E.; Varma, M.G.; Sarin, A. Risk Factors and Outcomes Associated with Postoperative Ileus Following Ileostomy Formation: A Retrospective Study. Perioper. Med. 2021, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Gan, T.J. Peri-Operative Fluid Management to Enhance Recovery. Anaesthesia 2015, 71, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.H.; Lobo, D. Fluids and Gastrointestinal Function. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2011, 14, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, R.; Cheong, D.M.; Wong, K.S.; Lee, B.M.K.; Liew, Q.Y. Prospective Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Pre- and Postoperative Administration of a COX-2-Specific Inhibitor as Opioid-Sparing Analgesia in Major Colorectal Surgery. Color. Dis. 2007, 9, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tan, Z.; Chen, J.; Lou, F.; Chen, W. Intravenous Flurbiprofen Axetil Accelerates Restoration of Bowel Function after Colorectal Surgery. Can. J. Anaesth. 2008, 55, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-Y.; Ko, T.-L.; Wen, Y.-R.; Wu, S.-C.; Chou, Y.-H.; Yien, H.-W.; Kuo, C.-D. Opioid-Sparing Effects of Ketorolac and Its Correlation with the Recovery of Postoperative Bowel Function in Colorectal Surgery Patients: A Prospective Randomized Double-Blinded Study. Clin. J. Pain 2009, 25, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murni, I.K.; Duke, T.; Kinney, S.; Daley, A.J.; Wirawan, M.T.; Soenarto, Y. Risk Factors for Healthcare-Associated Infection among Children in a Low-and Middle-Income Country. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammendola, M.; Ammerata, G.; Filice, F.; Filippo, R.; Ruggiero, M.; Romano, R.; Memeo, R.; Pessaux, P.; Navarra, G.; Montemurro, S.; et al. Anastomotic Leak Rate and Prolonged Postoperative Paralytic Ileus in Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Surgery for Colo-Rectal Cancer After Placement of No-Coil Endoanal Tube. Surg. Innov. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltazar, G.A.; Betler, M.P.; Akella, K.; Khatri, R.; Asaro, R.; Chendrasekhar, A. Effect of Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment on Incidence of Postoperative Ileus and Hospital Length of Stay in General Surgical Patients. J. Am. Osteopat. Assoc. 2013, 113, 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- MacVicar, E.; Cullen, F.; Kastora, S.L.; Parnaby, C.; Mackay, C.; Ramsay, G. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Post-Operative Oral Fluid Intake on Ileus Following Elective Colorectal Surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2022, 103, 106651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latifi, R.; Levy, L.; Reddy, M.; Okumura, K.; Smiley, A. Delayed Operation as a Major Risk Factor for Mortality Among Elderly Patients with Ventral Hernia Admitted Emergently: An Analysis of 33,700 Elderly Patients. Surg. Technol. Int. 2021, 39, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, N.; Smiley, A.; Goud, M.; Lin, C.; Latifi, R. Risk Factors of Mortality in Patients Hospitalized with Chronic Duodenal Ulcers. Am. Surg. 2021, 88, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, L.; Smiley, A.; Latifi, R. Independent Predictors of In-Hospital Mortality in Elderly and Non-Elderly Adult Patients Undergoing Emergency Admission for Hemorrhoids in the USA: A 10-Year National Dataset. Am. Surg. 2022, 88, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiley, A.; Levy, L.; Latifi, R. Risk Factors for Mortality in Patients with Ventral Hernia Admitted Emergently: An Analysis of 48,539 Adult Patients. Surg. Technol. Int. 2021, 39, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makary, M.A.; Segev, D.L.; Pronovost, P.J.; Syin, D.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Patel, P.; Takenaga, R.; Devgan, L.; Holzmueller, C.G.; Tian, J.; et al. Frailty as a Predictor of Surgical Outcomes in Older Patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2010, 210, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritt, M.; Ritt, J.I.; Sieber, C.C.; Gaßmann, K.-G. Comparing the Predictive Accuracy of Frailty, Comorbidity, and Disability for Mortality: A 1-Year Follow-up in Patients Hospitalized in Geriatric Wards. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, S.; Aalberg, J.J.; Soriano, R.P.; Divino, C.M. New 5-Factor Modified Frailty Index Using American College of Surgeons NSQIP Data. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2018, 226, 173–181.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadaya, J.; Mandelbaum, A.; Sanaiha, Y.; Benharash, P. Impact of Frailty on Clinical Outcomes and Hospitalization Costs Following Elective Colectomy. Am. Surg. 2021, 87, 1589–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Mabeza, R.M.; Verma, A.; Sakowitz, S.; Tran, Z.; Hadaya, J.; Lee, H.; Benharash, P. Association of Frailty with Outcomes after Elective Colon Resection for Diverticular Disease. Surgery 2022, 172, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkat, R.; Pandit, V.; Telemi, E.; Trofymenko, O.; Pandian, T.K.; Nfonsam, V.N. Frailty Predicts Morbidity and Mortality after Colectomy for Clostridium Difficile Colitis. Am. Surg. 2018, 84, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogal, H.; Vermilion, S.A.; Dodson, R.; Hsu, F.-C.; Howerton, R.; Shen, P.; Clark, C.J. Modified Frailty Index Predicts Morbidity and Mortality After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Qi, X. Association of Frailty with Delayed Recovery of Gastrointestinal Function after Elective Colorectal Cancer Resections. J. Investig. Surg. 2018, 33, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maine, R.G.; Kajombo, C.; Purcell, L.; Gallaher, J.R.; Reid, T.D.; Charles, A.G. Effect of In-Hospital Delays on Surgical Mortality for Emergency General Surgery Conditions at a Tertiary Hospital in Malawi. BJS Open 2019, 3, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeds, I.L.; Jones, C.; DiBrito, S.R.; Sakran, J.V.; Haut, E.R.; Kent, A.J. Delay in Emergency Hernia Surgery Is Associated with Worse Outcomes. Surg. Endosc. 2020, 34, 4562–4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, L.; Smiley, A.; Latifi, R. Independent Predictors of In-Hospital Mortality in Patients Undergoing Emergency Admission for Arterial embolism and Thrombosis in the USA: A 10-Year National Dataset. Kos. Med. J. 2021, 3, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, L.; Smiley, A.; Latifi, R. Mortality in Emergently Admitted Patients with Empyema: An Analysis of 18,033 Patients. Kos. Med. J. 2021, 8, 1612. [Google Scholar]

- Chagpar, A.B.; Howard-McNatt, M.; Chiba, A.; Levine, E.A.; Gass, J.S.; Gallagher, K.; Lum, S.; Martinez, R.; Willis, A.I.; Fenton, A.; et al. Factors Affecting Time to Surgery in Breast Cancer Patients. Am. Surg. 2022, 88, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.; Khu, K.J.; Kaderali, Z.; Bernstein, M. Delays in the Operating Room: Signs of an Imperfect System. Can. J. Surg. 2010, 53, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harders, M.; Malangoni, M.A.; Weight, S.; Sidhu, T. Improving Operating Room Efficiency through Process Redesign. Surgery 2006, 140, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overdyk, F.J.; Harvey, S.C.; Fishman, R.L.; Shippey, F. Successful Strategies for Improving Operating Room Efficiency at Academic Institutions. Anesth. Analg. 1998, 86, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolthuis, A.M.; Bislenghi, G.; Lambrecht, M.; Fieuws, S.; Overstraeten, A.D.B.V.; Boeckxstaens, G.; D’Hoore, A. Preoperative Risk Factors for Prolonged Postoperative Ileus after Colorectal Resection. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2017, 32, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hain, E.; Maggiori, L.; Mongin, C.; La Denise, J.P.A.; Panis, Y. Risk Factors for Prolonged Postoperative Ileus after Laparoscopic Sphincter-Saving Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer: An Analysis of 428 Consecutive Patients. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapuis, P.H.; Bokey, L.; Keshava, A.; Rickard, M.J.; Stewart, P.; Young, C.J.; Dent, O.F. Risk Factors for Prolonged Ileus after Resection of Colorectal Cancer: An Observational Study of 2400 Consecutive Patients. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, M.; Biondo, S.; Fraccalvieri, D.; Frago, R.; Golda, T.; Kreisler, E. Risk Factors for Prolonged Postoperative Ileus after Colorectal Cancer Surgery. World J. Surg. 2012, 36, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, K.E.; Hahn, A.; Hart, A.; Kahl, A.; Charlton, M.; Kapadia, M.R.; Hrabe, J.E.; Cromwell, J.W.; Hassan, I.; Gribovskaja-Rupp, I. Male Sex, Ostomy, Infection, and Intravenous Fluids Are Associated with Increased Risk of Postoperative Ileus in Elective Colorectal Surgery. Surgery 2021, 170, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceretti, A.P.; Maroni, N.; Longhi, M.; Giovenzana, M.; Santambrogio, R.; Barabino, M.; Luigiano, C.; Radaelli, G.; Opocher, E. Risk Factors for Prolonged Postoperative Ileus in Adult Patients Undergoing Elective Colorectal Surgery: An Observational Cohort Study. Rev. Recent Clin. Trials 2018, 13, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Schrag, H.J.; Goos, M.; Obermaier, R.; Hopt, U.T.; Baier, P.K. Transanal Endoscopic Tube Decompression of Acute Colonic Obstruction: Experience with 51 Cases. Surg. Endosc. 2008, 22, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Book, T.; Kirstein, M.M.; Schneider, A.; Manns, M.P.; Voigtländer, T. Endoscopic Decompression of Acute Intestinal Distension Is Associated with Reduced Mortality in Critically Ill Patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, T.; Shimura, T.; Sakamoto, E.; Kurumiya, Y.; Komatsu, S.; Iwasaki, H.; Nomura, S.; Kanie, H.; Hasegawa, H.; Orito, E.; et al. Preoperative Drainage Using a Transanal Tube Enables Elective Laparoscopic Colectomy for Obstructive Distal Colorectal Cancer. Endoscopy 2013, 45, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilz, T.O.; Stoffels, B.; Straßburg, C.; Schild, H.H.; Kalff, J.C. Ileus in Adults. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2017, 114, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elgar, G.; Smiley, P.; Smiley, A.; Feingold, C.; Latifi, R. Age Increases the Risk of Mortality by Four-Fold in Patients with Emergent Paralytic Ileus: Hospital Length of Stay, Sex, Frailty, and Time to Operation as Other Risk Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9905. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169905

Elgar G, Smiley P, Smiley A, Feingold C, Latifi R. Age Increases the Risk of Mortality by Four-Fold in Patients with Emergent Paralytic Ileus: Hospital Length of Stay, Sex, Frailty, and Time to Operation as Other Risk Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):9905. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169905

Chicago/Turabian StyleElgar, Guy, Parsa Smiley, Abbas Smiley, Cailan Feingold, and Rifat Latifi. 2022. "Age Increases the Risk of Mortality by Four-Fold in Patients with Emergent Paralytic Ileus: Hospital Length of Stay, Sex, Frailty, and Time to Operation as Other Risk Factors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 9905. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169905

APA StyleElgar, G., Smiley, P., Smiley, A., Feingold, C., & Latifi, R. (2022). Age Increases the Risk of Mortality by Four-Fold in Patients with Emergent Paralytic Ileus: Hospital Length of Stay, Sex, Frailty, and Time to Operation as Other Risk Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9905. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169905