How Do Religiosity and Spirituality Associate with Health-Related Outcomes of Adolescents with Chronic Illnesses? A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Defining Religiosity and Spirituality

1.2. Conceptualizing Chronicity

1.3. Adolescence, Chronic Illness, Religiosity, and Spirituality

1.4. The Current Study

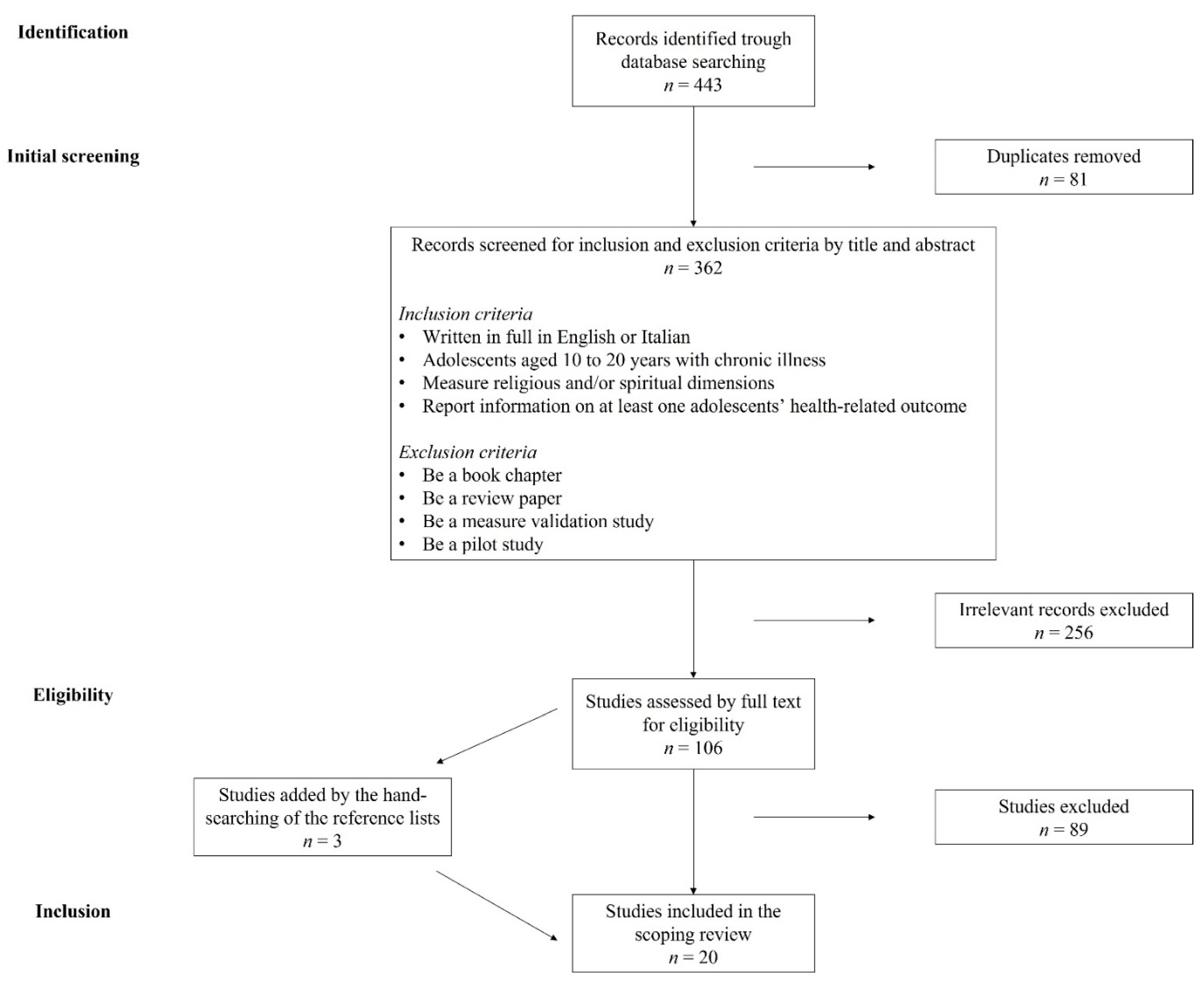

2. Method

2.1. Selection of studies

2.2. Classification of Studies

3. Results

3.1. Positive Relationships of Religiosity and Spirituality with Health-Related Outcomes of Adolescents with Chronic Illnesses

3.2. Negative Relationships of Religiosity and Spirituality with Health-Related Outcomes of Adolescents with Chronic Illnesses

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Christie, D.; Viner, R. Adolescent Development. BMJ 2005, 330, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, R.E. Adolescent Brain Development: A Period of Vulnerabilities and Opportunities. Keynote Address. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacomba-Trejo, L.; Valero-Moreno, S.; Montoya-Castilla, I.; Pérez-Marín, M. Psychosocial Factors and Chronic Illness as Predictors for Anxiety and Depression in Adolescence. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 568941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suris, J.-C.; Michaud, P.-A.; Viner, R. The Adolescent with a Chronic Condition. Part I: Developmental Issues. Arch. Dis. Child. 2004, 89, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkelbach van der Sprenkel, E.E.; Nijhof, S.L.; Dalmeijer, G.W.; Onland-Moret, N.C.; de Roos, S.A.; Lesscher, H.M.B.; van de Putte, E.M.; van der Ent, C.K.; Finkenauer, C.; Stevens, G.W.J.M. Psychosocial Functioning in Adolescents Growing up with Chronic Disease: The Dutch HBSC Study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.L.; Revenson, T.A.; Tennen, H. Health Psychology: Psychological Adjustment to Chronic Disease. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 565–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, P.E.; Roeser, R.W. Religion and Spirituality in Adolescent Development. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology; Lerner, R.M., Steinberg, L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 435–478. ISBN 978-0-470-47919-3. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.L. Religiousness/Spirituality and Health: A Meaning Systems Perspective. J. Behav. Med. 2007, 30, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drutchas, A.; Anandarajah, G. Spirituality and Coping with Chronic Disease in Pediatrics. R. I. Med. J. 2013 2014, 97, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton-Jones, D.; Haglund, K. The Role of Spirituality and Religiosity in Persons Living With Sickle Cell Disease: A Review of the Literature. J. Holist. Nurs. 2016, 34, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, N.; Mrug, S.; Wolfe, K.; Schwebel, D.; Wallander, J. Spiritual Coping, Psychosocial Adjustment, and Physical Health in Youth with Chronic Illness: A Meta-Analytic Review. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damsma Bakker, A.; van Leeuwen, R.R.; Roodbol, P.F. The Spirituality of Children with Chronic Conditions: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 43, e106–e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, P.C.; Pargament, K., II; Hood, R.W.; Mccullough, J.M.E.; Michael, E.; Swyers, J.P.; Larson, D.B.; Zinnbauer, B.J. Conceptualizing Religion and Spirituality: Points of Commonality, Points of Departure. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2000, 30, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Thoresen, C.E. Spirituality, Religion, and Health: An Emerging Research Field. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worthington, E.L.; Hook, J.N.; Davis, D.E.; McDaniel, M.A. Religion and Spirituality. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinnbauer, B.J.; Pargament, K.I. Religiousness and Spirituality. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality; Paloutzian, R.F., Park, C.L., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 21–42. ISBN 978-1-57230-922-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, P.C.; Pargament, K.I. Advances in the Conceptualization and Measurement of Religion and Spirituality: Implications for Physical and Mental Health Research. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, P.L.; Scales, P.C.; Syvertsen, A.K.; Roehlkepartain, E.C. Is Youth Spiritual Development a Universal Developmental Process? An International Exploration. J. Posit. Psychol. 2012, 7, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.E. Religion and Identity: The Role of Ideological, Social, and Spiritual Contexts. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2003, 7, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.E. Spirituality as Fertile Ground for Positive Youth Development. In Positive Youth Development & Spirituality: From Theory to Research; Lerner, R.M., Roeser, R.W., Phelps, E., Eds.; Templeton Foundation Press: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008; pp. 55–73. ISBN 978-1-59947-143-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, B.J.; Pargament, K.I.; Cole, B.; Rye, M.S.; Butter, E.M.; Belavich, T.G.; Hipp, K.M.; Scott, A.B.; Kadar, J.L. Religion and Spirituality: Unfuzzying the Fuzzy. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1997, 36, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannello, N.M.; Musso, P.; Coco, A.L.; Inguglia, C. Il contributo della religione e della spiritualità allo sviluppo positivo dei giovani. Una rassegna sistematica della letteratura. G. Ital. Psicol. 2020, 47, 907–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, J.L.; Eccles, J.S. The Relation between Spiritual Development and Identity Processes. In The Handbook of Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 252–265. ISBN 978-0-7619-3078-5. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Integrating the Response to Mental Disorders and Other Chronic Diseases in Health Care Systems; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, R.E.K.; Bauman, L.J.; Westbrook, L.E.; Coupey, S.M.; Ireys, H.T. Framework for Identifying Children Who Have Chronic Conditions: The Case for a New Definition. J. Pediatr. 1993, 122, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Halloran, J.; Miller, G.C.; Britt, H. Defining Chronic Conditions for Primary Care with ICPC-2. Fam. Pract. 2004, 21, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, A. What Is a Chronic Disease? The Effects of a Re-Definition in HIV and AIDS. Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 39, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubkin, I.M.; Larsen, P.D. What Is Chronicity? In Chronic Illness: Impact and Intervention; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Sudbury, ON, Canada, 2002; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, P.D. Chronicity. In Lubkin’s Chronic Illness: Impact and Intervention; Larsen, P.D., Ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Curtin, M.; Lubkin, I. What Is Chronicity? In Chronic Illness: Impact and Intervention; Lubkin, I.M., Ed.; Jones and Barnett: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, A.; Silber, T.J.; Lyon, M. Psychosocial Aspects of Chronic Illness in Adolescence. Indian J. Pediatr. 1999, 66, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.M.; Gibson, F.; Franck, L.S. The Experience of Living with a Chronic Illness during Adolescence: A Critical Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 3083–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, P.-A.; Suris, J.-C.; Viner, R. The Adolescent with a Chronic Condition. Part II: Healthcare Provision. Arch. Dis. Child. 2004, 89, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, C.A.; Bond, L.; Johnson, M.W.; Forer, D.L.; Boyce, M.F.; Sawyer, S.M. Adolescent Chronic Illness: A Qualitative Study of Psychosocial Adjustment. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2003, 32, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- King, P.E.; Carr, D.; Boitor, C. Religion, Spirituality, Positive Youth Development, and Thriving. In Advances in Child Development and Behavior; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 41, pp. 161–195. ISBN 978-0-12-386492-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton, S.; Zebracki, K.; Rosenthal, S.L.; Tsevat, J.; Drotar, D. Religion/Spirituality and Adolescent Health Outcomes: A Review. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 38, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.A.; Nelson, J.M.; Moore, J.P.; King, P.E. Processes of Religious and Spiritual Influence in Adolescence: A Systematic Review of 30 Years of Research. J. Res. Adolesc. 2019, 29, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Allen, P.; Peckham, S.; Goodwin, N. Asking the Right Questions: Scoping Studies in the Commissioning of Research on the Organisation and Delivery of Health Services. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2008, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inguglia, C.; Musso, P.; Iannello, N.M.; Lo Coco, A. The Contribution of Religiosity and Optimism on Well-Being of Youth and Emerging Adults in Italy. In Well-Being of Youth and Emerging Adults across Cultures; Dimitrova, R., Ed.; Cross-Cultural Advancements in Positive Psychology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 12, pp. 19–33. ISBN 978-3-319-68362-1. [Google Scholar]

- Roger, K.S.; Hatala, A. Religion, Spirituality & Chronic Illness: A Scoping Review and Implications for Health Care Practitioners. J. Relig. Spirit. Soc. Work Soc. Thought 2018, 37, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, K.; Ahmad, W.I.U. Living a ‘Normal’ Life: Young People Coping with Thalassaemia Major or Sickle Cell Disorder. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 53, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, W.A.; Machado, J.R.; Leite, A.C.A.B.; Caldeira, S.; Vieira, M.; da Rocha, S.S.; Nascimento, L.C. Spiritual Needs of Brazilian Children and Adolescents with Chronic Illnesses: A Thematic Analysis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 60, e39–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, K.; D’Angelo, L.J.; Lyon, M.E. An Exploratory Study of HIV+ Adolescents’ Spirituality: Will You Pray with Me? J. Relig. Health 2013, 52, 1253–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton-Jones, D.; Haglund, K.; Belknap, R.A.; Schaefer, J.; Thompson, A.A. Spirituality and Religiosity in Adolescents Living With Sickle Cell Disease. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 38, 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, S.; Weekes, J.C.; McGrady, M.E.; Rosenthal, S.L.; Yi, M.S.; Pargament, K.; Succop, P.; Roberts, Y.H.; Tsevat, J. Spirituality and Religiosity in Urban Adolescents with Asthma. J. Relig. Health 2012, 51, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cotton, S.; Kudel, I.; Roberts, Y.H.; Pallerla, H.; Tsevat, J.; Succop, P.; Yi, M.S. Spiritual Well-Being and Mental Health Outcomes in Adolescents With or Without Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 44, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, C.M.; Mrug, S.; Grossoehme, D.; Leon, K.; Thomas, L.; Troxler, B. Reciprocal Links Between Physical Health and Coping Among Adolescents With Cystic Fibrosis. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 46, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elissa, K.; Sparud-Lundin, C.; Axelsson, Å.B.; Khatib, S.; Bratt, E.-L. Struggling and Overcoming Daily Life Barriers Among Children With Congenital Heart Disease and Their Parents in the West Bank, Palestine. J. Fam. Nurs. 2018, 24, 585–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossoehme, D.H.; Friebert, S.; Baker, J.N.; Tweddle, M.; Needle, J.; Chrastek, J.; Thompkins, J.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Y.I.; Lyon, M.E. Association of Religious and Spiritual Factors With Patient-Reported Outcomes of Anxiety, Depressive Symptoms, Fatigue, and Pain Interference Among Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e206696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossoehme, D.H.; Szczesniak, R.D.; Mrug, S.; Dimitriou, S.M.; Marshall, A.; McPhail, G.L. Adolescents’ Spirituality and Cystic Fibrosis Airway Clearance Treatment Adherence: Examining Mediators. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 41, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Grossoehme, D.H.; Szczesniak, R.; McPhail, G.L.; Seid, M. Is Adolescents’ Religious Coping with Cystic Fibrosis Associated with the Rate of Decline in Pulmonary Function?—A Preliminary Study. J. Health Care Chaplain. 2013, 19, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landolt, M.; Vollrath, M.; Ribi, K. Predictors of Coping Strategy Selection in Paediatric Patients. Acta Paediatr. 2002, 91, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, M.E.; Garvie, P.; He, J.; Malow, R.; McCarter, R.; D’Angelo, L.J. Spiritual Well-Being Among HIV-Infected Adolescents and Their Families. J. Relig. Health 2014, 53, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, N.; Mrug, S.; Guion, K. Spiritual Coping and Psychosocial Adjustment of Adolescents With Chronic Illness: The Role of Cognitive Attributions, Age, and Disease Group. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, N.; Mrug, S.; Hensler, M.; Guion, K.; Madan-Swain, A. Spiritual Coping and Adjustment in Adolescents With Chronic Illness: A 2-Year Prospective Study. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014, 39, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, N.; Mrug, S.; Britton, L.; Guion, K.; Wolfe, K.; Gutierrez, H. Spiritual Coping Predicts 5-Year Health Outcomes in Adolescents with Cystic Fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2014, 13, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Silveira, A.; Neves, E.T. The Social Network of Adolescents Who Need Special Health Care. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2019, 72, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, A.A.; Eisen, A.M.; Abdul-Rahman, H.Q.; Zouros, A.; Norman, S. The Moderating Role of Spirituality on Quality of Life and Depression among Adolescents with Spina Bifida. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanattheerakul, C.; Tangvoraphonkchai, J.; Pimsa, W. Spiritual Needs and Practice in Chronically Ill Children and Their Families in the Isan Region of Thailand. Int. J. Child. Spirit. 2020, 25, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehnder, D.; Prchal, A.; Vollrath, M.; Landolt, M.A. Prospective Study of the Effectiveness of Coping in Pediatric Patients. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2006, 36, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unantenne, N.; Warren, N.; Canaway, R.; Manderson, L. The Strength to Cope: Spirituality and Faith in Chronic Disease. J. Relig. Health 2013, 52, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pargament, K.I. Is Religion Good for Your Health? It Depends; Heritage Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, K.I.; Abu Raiya, H. A Decade of Research on the Psychology of Religion and Coping: Things We Assumed and Lessons We Learned. Psyke Logos 2007, 28, 742–766. [Google Scholar]

- Iannello, N.M.; Hardy, S.A.; Musso, P.; Lo Coco, A.; Inguglia, C. Spirituality and Ethnocultural Empathy among Italian Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Religious Identity Formation Processes. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2019, 11, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Alberts, A.E.; Anderson, P.M.; Dowling, E.M. On Making Humans Human: Spirituality and the Promotion of Positive Youth Development. In The Handbook of Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 60–72. ISBN 978-0-7619-3078-5. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, P.; Ai, A.L.; Aydin, N.; Frey, D.; Haslam, S.A. The Relationship between Religious Identity and Preferred Coping Strategies: An Examination of the Relative Importance of Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Coping in Muslim and Christian Faiths. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2010, 14, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.M.; Trevino, D.B.; Geske, J.A.; Vanderpool, H. Religious Coping and Mental Health Outcomes: An Exploratory Study of Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Patients. EXPLORE 2012, 8, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, T.B. Religion and Socioeconomic Status in Developing Nations: A Comparative Approach. Soc. Compass 2013, 60, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrett, N.; Eccles, J. The Passage to Adulthood: Challenges of Late Adolescence. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2006, 2006, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K.I.; Smith, B.W.; Koenig, H.G.; Perez, L. Patterns of Positive and Negative Religious Coping with Major Life Stressors. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1998, 37, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L. Health Professionals Caring for Chronically Ill Adolescents: Adolescents’ Perspectives. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 1998, 3, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, R.D.; Krause, N. Religion, Mental Health, and Well-Being: Social Aspects. In Religion, Personality, and Social Behavior; Saroglou, V., Ed.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 255–280. ISBN 978-1-136-44984-0. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Participants | Age Range (years) | Country | Characterization of the Sample | Instruments/Measures | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atkin and Ahmad, 2001 [42] | N = 51 Female = 27 | 10–19 | UK | Disease: Sickle cell disorder (SCD) or thalassemia major (TM) Religious Affiliation: Islamic or Christian | Semi-structured interviews (administered twice over a 6-month period) to explore the strategies and resources young people used to cope with their disorders by encouraging them to talk about their illness within their social context (i.e., family relationships, life transitions, and social networks). | Age, gender, and ethnicity influenced how spiritual belief was utilized as a resource. Youth with TM were mostly Islamic and generally saw Allah as a source of strength. Their resentment toward the “unfairness” of the illness was transitory. Most of them prayed on a regular basis for a cure (<13 years) or for gaining strength (older participants). In general, younger children and girls passively accepted Islam (i.e., they followed their family), while older boys (> 16 years) were more active believers (e.g., they often read the Koran). Accepting one’s fate and “passing tests” sent by God helped them to make sense of their condition. Youth with SCD were mostly Christian and adopted religion as a coping resource less frequently. Most of them prayed to God for need (e.g., children < 12 for relief), but sometimes had the feeling of being ignored. They felt that, if they were generally good, they would not have a crisis (reward vs. punishment). Age seemed to diminish the importance of religion. |

| Alvarenga et al., 2021 [43] | N = 35 Female = 17 | 7–18 | Brazil | Disease: Cancer, cystic fibrosis, or type 1 diabetes mellitus. Religious Affiliation: 14 Evangelical; 13 Catholic; 1 Umbanda (Afro-Brazilian religion); 1 Spiritism; 1 No religion, but spiritual (believes in something); 0 No religion and not spiritual (does not believe in anything); 5 Atheist (does not believe in God) | Individual audio-recorded interviews with photo-elicitation centered on the experience of the disease and the role of religion/spirituality in the life journey, life meaning, religious/spiritual beliefs, and resources used to cope with the disease (religious/spiritual beliefs, family, friends, and health professionals). | Children and adolescents with chronic illnesses had five spiritual needs while in the hospital: (1) Need to integrate meaning and purpose in life, for instance, by believing that their disease was part of a plan of a benevolent God who wanted them to mature through their illness; (2) Need to sustain hope, especially about their future; faith is an element that helps to promote hope; (3) Need for expression of faith and to follow religious practices: they believed in a benevolent God who intervened in adverse or near-death situations, to keep them alive or heal them; they described the religious community as a source of support and comfort; (4) Need for comfort at the end of life by believing in a life after death (e.g., the existence of hell and paradise); (5) Need to connect with family and friends, as a source of faith, peace, and support while dealing with the illness and the finitude of life. They also found comfort in believing that, after their own deaths, they will be reunited with their deceased family members in a good place. Additionally, participants conveyed that not enough spiritual care was offered in the hospital due to the professionals’ lack of time and difficulty in dialogue on this subject. |

| Bernstein et al., 2013 [44] | N = 45 (nHIV = 19) Female = 28 | 12–21 M = 17.2 SD = 2.2 | USA | Disease: HIV Religious affiliation: 15 Baptist; 5 Church of Christ; 1 Lutheran; 1 Methodist; 7 Non-denominational Christian; 1 Orthodox Church; 1 Other Protestant; 2 Pentecostal; 3 Roman Catholic; 1 Southern Baptist; 1 Undesignated; 2 Other; 3 None | A survey packet containing the measures of spirituality/religiosity, quality of life measures, acceptance of spiritual discussions, and general demographic variables | Teens with HIV were more likely to endorse wanting their doctors to pray with them, feeling ‘‘God’s presence’’, being ‘‘part of a larger force’’, and feeling that ‘‘God had abandoned them’’ than their counterparts without HIV. |

| Clayton-Jones et al., 2016 [45] | N = 9 Female = 6 | 15–18 M = 16.2 | USA | Disease: Sickle cell disease (SCD) Religious affiliation: Baptist, Catholic, Pentecostal, and Presbyterian | A qualitative descriptive design was used. Two semi-structured interviews were conducted with adolescents. | Teens expressed that they drew from spirituality and religiosity to cope with SCD, but in different ways. Spirituality was seen to enhance their sense of connectedness with one another, nature, and the arts, which helped them to feel better, find purpose, and transcend their condition. Religiosity was seen in terms of a connection with God, also via the reading of scriptural metanarratives, which lead adolescents to gain new outlooks on their illness, strength, hope for the future, and frameworks for decision-making and reflection. |

| Cotton et al., 2012 [46] | N = 151 Female = 91 | 11–19 M = 15.8 SD = 1.8 | USA | Disease: Asthma Religious affiliation: 97 Protestant; 16 Catholic; 1 Jewish; 35 No Preference; 2 Other | Demographic data and adolescents’ religious preferences were collected via patient interviews. Asthma severity at the time of the study was collected via a clinical provider according to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute criteria (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute 2007). | African American race/ethnicity and having a religious preference were related to higher levels of spirituality/religiosity (S/R), including positive religious coping. With increasing clinical severity, adolescents’ preferences for including S/R in the medical setting grew. |

| Cotton et al., 2009 [47] | N = 154 (nIBD= 66) Female = 74 | 11–19 M = 15.1 SD = 2.0 | USA | Disease: Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Religious affiliation: - | Questionnaires were administered to measure spiritual (religious and existential) well-being, depression, emotional functioning, and health-related quality of life, as well as demographics, disease status, and their interactions. | Most adolescents believed that a Higher Power loved and cared about them, and more than half reported that their relationship with a Higher Power contributed to their well-being. Adolescents with and without IBD showed similar levels of both existential and religious well-being. However, the disease status moderated the relationship between spiritual well-being and mental health outcomes. Indeed, (a) the positive relationship between existential well-being and emotional functioning and (b) the inverse relationship between religious well-being and depressive symptoms were both stronger for adolescents with IBD than for their healthy peers. |

| D’Angelo et al., 2021 [48] | N = 79 Female = 43 | 12–18 M = 14.7 SD = 1.8 | USA | Disease: Cystic fibrosis Religious affiliation: 67 Christian, 4 Other, 8 No affiliation | Questionnaires assessing secular and religious/spiritual coping styles at two timepoints (18 months apart, on average). Health indicators, including pulmonary functioning, nutritional status, and days hospitalized, were obtained from medical records. | Poorer pulmonary functioning predicted higher levels of positive religious/spiritual coping, suggesting the resilience of adolescents with cystic fibrosis. More frequent hospitalizations, instead, may inhibit the use of adaptive coping strategies over time. |

| Elissa et al., 2018 [49] | N = 9 Female = 4 | 8–18 | Palestine | Disease: Congenital heart disease (CHD) Religious affiliation: Muslims | An inductive qualitative descriptive design with face-to-face interviews at home was applied. The interview guide included the following main questions: “Can you describe your CHD and how do you think it affects your daily life?”, “What is a typical day like for you right now?”, and “On a typical day, what sorts of things do you do that might set you apart from your friends?” | All children believed that everything in the universe, including health or illness, was controlled by God’s will, and, as consequence, it should be tolerated rather than objected. They adopted a sense of fatality about illness and reliance on God for managing the disease and controlling community pressure. Some participants also held the belief that God could heal illness, so they regularly engaged in religious practices, including reading from the Holy Qur’an and praying at a mosque as a means of coping and searching for support and hope. |

| Grossoehme et al., 2020 [50] | N =126 Female = 72 | 14–21 M = 16.9 SD = 1.9 | USA | Disease: Cancer Religious affiliation: 24 Agnostic/atheist/none, 90 Christian, 1 Hindu, 1 Jehovah’s Witness, 1 Jewish, 6 LDS/Mormon, 3 Missing | Sociodemographic data (i.e., age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, and household income); time since diagnosis, treatment status, study site; the importance of religion and spirituality to participants; religiousness/spirituality (i.e., feeling God’s presence, daily prayer, religious service attendance, being very religious, and being very spiritual); spiritual well-being (meaning/ peace and faith); and anxiety, depressive symptoms, fatigue, and pain interference. | Through a higher sense of meaning and peace: (a) experiencing God’s presence every day was indirectly related to anxiety, depressive symptoms, and fatigue; (b) being highly religious was indirectly related to anxiety, depressive symptoms, and fatigue; (c) being highly spiritual was indirectly associated with anxiety and depression. No links between spiritual scales and pain interference were found. |

| Grossoehme et al., 2016 [51] | N = 45 Female = 27 | 11–19 M = 13.8 SD = 2.2 | USA | Disease: Cystic fibrosis Religious affiliation: 19 Nondenominational Christian, 10 Protestant, 6 Roman Catholic, 6 None, 3 Other, 1 Did not disclose | Psychosocial, spiritual coping, treatment attitude (utility), subjective norms, sanctification of the body, self-efficacy, treatment intentions, and treatment adherence. | Lower levels of “spiritual struggle” (i.e., not asking for God’s help or questioning God’s love) and higher levels of “engaged spirituality” (i.e., positive religious coping, collaboration with God to solve problems, turning problems to God, or viewing one’s body as sacred) predicted treatment attitude (utility) as well as subjective behavioral norms, which, in combination with self-efficacy, predicted treatment intentions. Additionally, treatment intentions predicted adherence to airway clearing. |

| Grossoehme et al., 2013 [52] | N = 28 Female = 9 | 11–18 M = 13.5 | USA | Disease: Cystic fibrosis Religious affiliation: - | Religious coping (“negative religious coping styles” and “pleading style of religious coping for control”). | Adolescents who experienced lung function decline more quickly were more likely to use pleading or negative religious coping styles. A negative correlation existed between certain religious coping styles and longitudinal changes in lung functioning. Positive rates of change in lung functioning were related to less pleading. The probability of using any religious coping was lower for slower pulmonary function decline, but, when compared with pleading, the probability of engaging in any negative religious coping did not decrease as quickly. Hence, even when adolescents’ lung function was above the normal range of that of their healthier counterparts, they still used negative religious coping. |

| Landolt et al., 2002 [53] | N = 179 (ncancer = 26, ndiabetes = 48) Female = 69 | M = 10.2 SD = 2.3 | Switzerland | Disease: Cancer or type I diabetes mellitus Religious affiliation: - | Coping (i.e., active coping, distraction, avoidance, support seeking, and religiosity), functional status, and socioeconomic status | Patients used a wide range of coping strategies, but those of lower socioeconomic status turned to religious coping strategies far more frequently than their counterparts. |

| Lyon et al., 2014 [54] | N = 38 Female = 23 | 14–21 M = 16.6 SD = 2.3 | USA | Disease: HIV Religious affiliation: - | Spiritual well-being (faith and meaning/peace), psychological adjustment (depression and anxiety), and health-related quality of life. | Higher adolescents’ spiritual well-being was related to lower depression, lower anxiety, and greater life quality. |

| Reynolds et al., 2013 [55] | N = 128 Female = 59 | 12–18 M = 14.7 SD = 1.8 | USA | Disease: Cystic fibrosis or type 1 diabetes Religious affiliation: Predominantly Christian | Demographics, positive spiritual coping (i.e., seeking spiritual support or collaboration from God, as well as benevolent religious reappraisals) vs. negative spiritual coping (i.e., spiritual discontentment, negative reappraisals of God’s powers, or demonic reappraisals); attributional style; and adolescents’ adjustment (internalizing and externalizing problems). | Positive spiritual coping was related to less internalizing and externalizing problems. Negative spiritual coping was associated with more externalizing problems, and solely for teens with cystic fibrosis, internalizing problems as well. Optimistic attributions mediated the effects of positive spiritual coping among diabetic teens. |

| Reynolds et al., 2014 [56] | Same as in the previous study (at baseline) N = 87 (at follow-up) | 12–18 at baseline M = 14.7 SD = 1.8 Follow-up age was ~2 years after baseline M = 1.78 SD = 0.80 | USA | Disease: Cystic fibrosis or type 1 diabetes Religious affiliation: 11% no religious affiliation, 78% Protestant, 8% Catholic, 3% other. | Spiritual coping and adjustment, adolescent adjustment (2 years apart). | Over time, less negative spiritual coping and depressive symptoms were predicted by positive spiritual coping, whereas more positive spiritual coping was predicted by negative spiritual coping. Higher levels of negative spiritual coping and conduct problems over time were predicted by depressive symptoms. The results did not vary by disease. |

| Reynolds et al., 2014 [57] | N = 46 Female = 23 | 12–18 M = 14.7 SD = 1.9 | USA | Disease: Cystic fibrosis Religious affiliation: Predominately Christian | Spiritual coping, secular coping, pulmonary function, BMI percentile, hospitalizations, baseline medical complications, and demographics. | Positive spiritual coping was linked to a slower decrease in pulmonary function, stable vs. declining nutritional status, and fewer days spent in the hospital over the course of five years. Negative spiritual coping was linked to a higher BMI percentile at baseline, but not to long-term health outcomes. |

| Silveira and Neves, 2019 [58] | N = 35 | 12–18 | Brazil | Disease: Children and adolescents who need special healthcare services Religious affiliation: - | A qualitative, descriptive, and exploratory study. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with adolescents, followed by the construction of genograms and ecomaps. | Some adolescents saw the church as a source of spiritual support that enabled them to cope with the challenges created by their medical conditions. The search for spirituality as emotional support and a source of strength aided in the socialization process, as the church and the youth group became part of the adolescent’s social network. |

| Taha et al., 2020 [59] | N = 58 Female = 29 | 13–20 M = 16.2 SD = 2.2 | USA | Disease: Spina bifida Religious affiliation: 32 Protestant; 20 Catholic; 2 Agnostic; 2 Atheist; 2Other | Spirituality; depression and quality of life; and distress. | Depressive symptoms fully mediated the association between symptom distress and quality of life, and higher levels of spirituality moderated the relationship between depressive symptoms and quality of life. Adolescents with more severe symptoms (i.e., Welch’s shunt status, level of lesion, and ambulation status) had higher spirituality. Contrary to predictions, when depression symptoms were mild to moderate, adolescents with higher levels of spirituality had a lower quality of life. |

| Thanattheerakul et al., 2020 [60] | N = 17 Female = 6 | 10–18 M = 13.5 SD = 2.09 | Thailand | Disease: Cancer (35.3%), bone and joint (29.4%), neurology and urology (both 11.8%), and endocrine and immunology (both 5.85%). Religious affiliation: Buddhist | Data were collected by using a questionnaire, in-depth interviews with questions adapted from the Spiritual Assessment Scale (SAS; O’Brien, 2014), and non-participant observation | Children reported that, when they were sick, their mothers and other family members served as their spiritual anchors, and their physicians and sacred spirituals were significant as well. They afforded them the inner strength to battle their illness and live their lives. In addition, interviews showed that (a) children believed that doing good deeds could protect them, especially during illness; (b) spiritual practices (e.g., prayer, requesting blessings on sacred things) increased when they were ill and had credit to bring inner peace and relief. |

| Zehnder et al., 2006 [61] | N = 161 (ndisease = 60) Female = 63 (ndisease = 24) | 6–15 M = 10.0 SD = 2.3 | Switzerland | Disease: 25 type 1 diabetes, 23 cancer, and 12 epilepsy. Religious affiliation: - | Coping (i.e., active coping, distraction, avoidance, support seeking, and religious coping, namely asking for God’s help and praying to God for comfort), child post-traumatic stress reactions, behavioral problems, socio-economic status, functional status, and preceding life events. | Religious coping reduced post-traumatic stress symptoms among (injured and) newly diagnosed children with a chronic disease after 1 year. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iannello, N.M.; Inguglia, C.; Silletti, F.; Albiero, P.; Cassibba, R.; Lo Coco, A.; Musso, P. How Do Religiosity and Spirituality Associate with Health-Related Outcomes of Adolescents with Chronic Illnesses? A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013172

Iannello NM, Inguglia C, Silletti F, Albiero P, Cassibba R, Lo Coco A, Musso P. How Do Religiosity and Spirituality Associate with Health-Related Outcomes of Adolescents with Chronic Illnesses? A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013172

Chicago/Turabian StyleIannello, Nicolò M., Cristiano Inguglia, Fabiola Silletti, Paolo Albiero, Rosalinda Cassibba, Alida Lo Coco, and Pasquale Musso. 2022. "How Do Religiosity and Spirituality Associate with Health-Related Outcomes of Adolescents with Chronic Illnesses? A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013172

APA StyleIannello, N. M., Inguglia, C., Silletti, F., Albiero, P., Cassibba, R., Lo Coco, A., & Musso, P. (2022). How Do Religiosity and Spirituality Associate with Health-Related Outcomes of Adolescents with Chronic Illnesses? A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013172