Interethnic Influencing Factors Regarding Buttocks Body Image in Women from Nigeria, Germany, USA and Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Present Study

1.2. Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. IP Classification and Verification of Origin

2.3. Classification and Regression Tree (CART) Analysis

2.4. Instagram Influencer Data Collection

2.5. Statistics and Data Presentation

3. Results

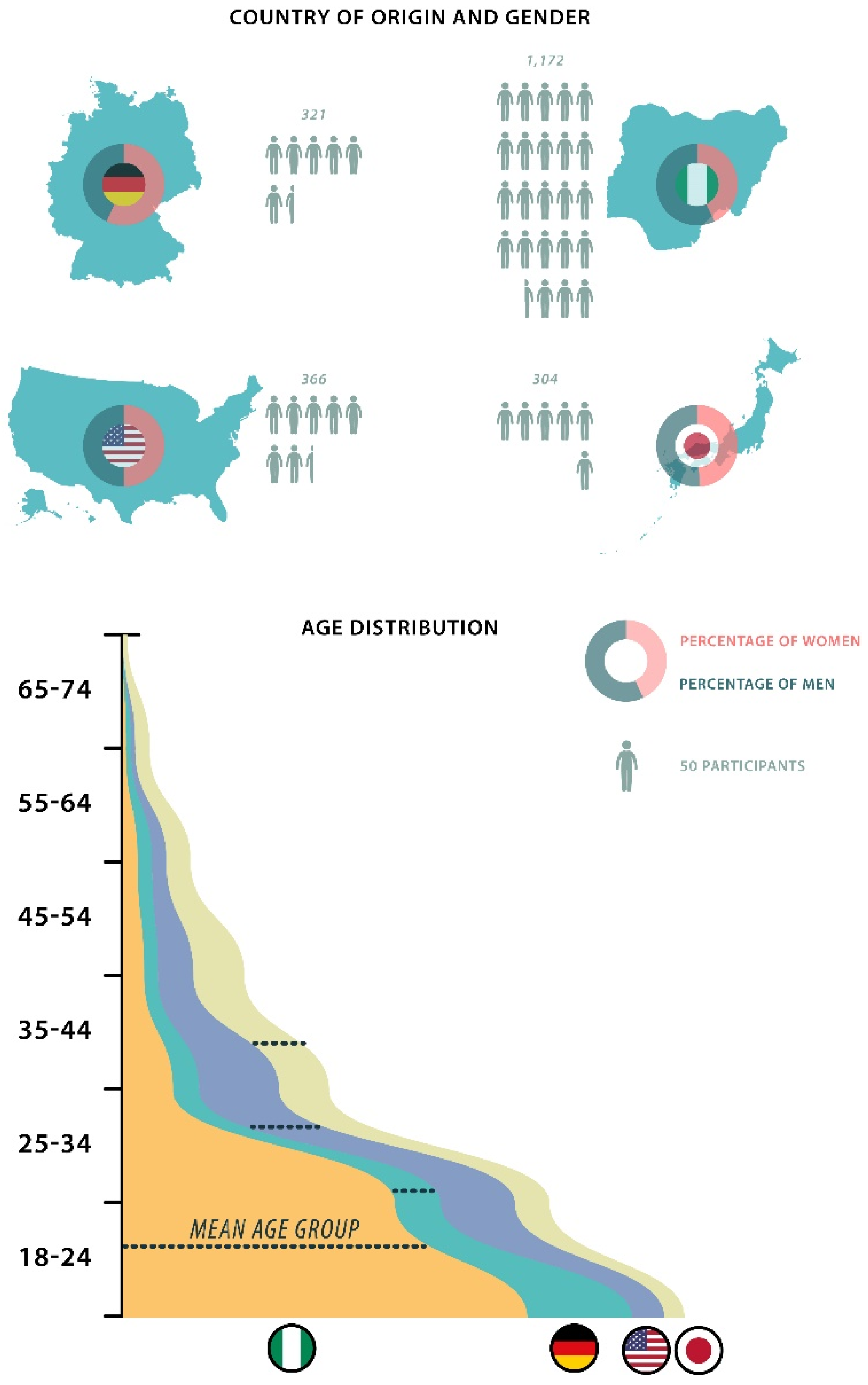

3.1. Survey Population

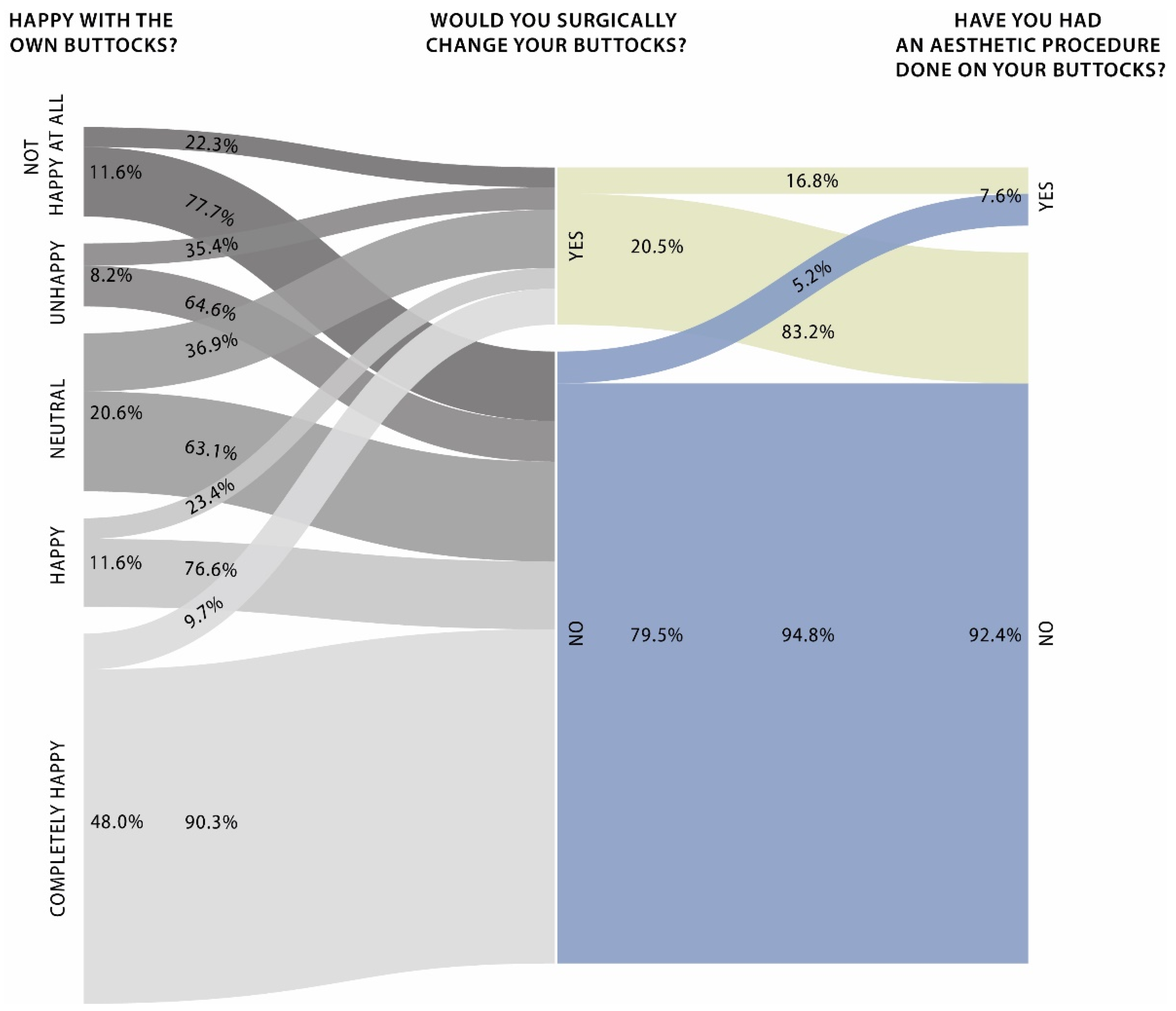

3.2. Perception of One’s Own Buttocks in Women

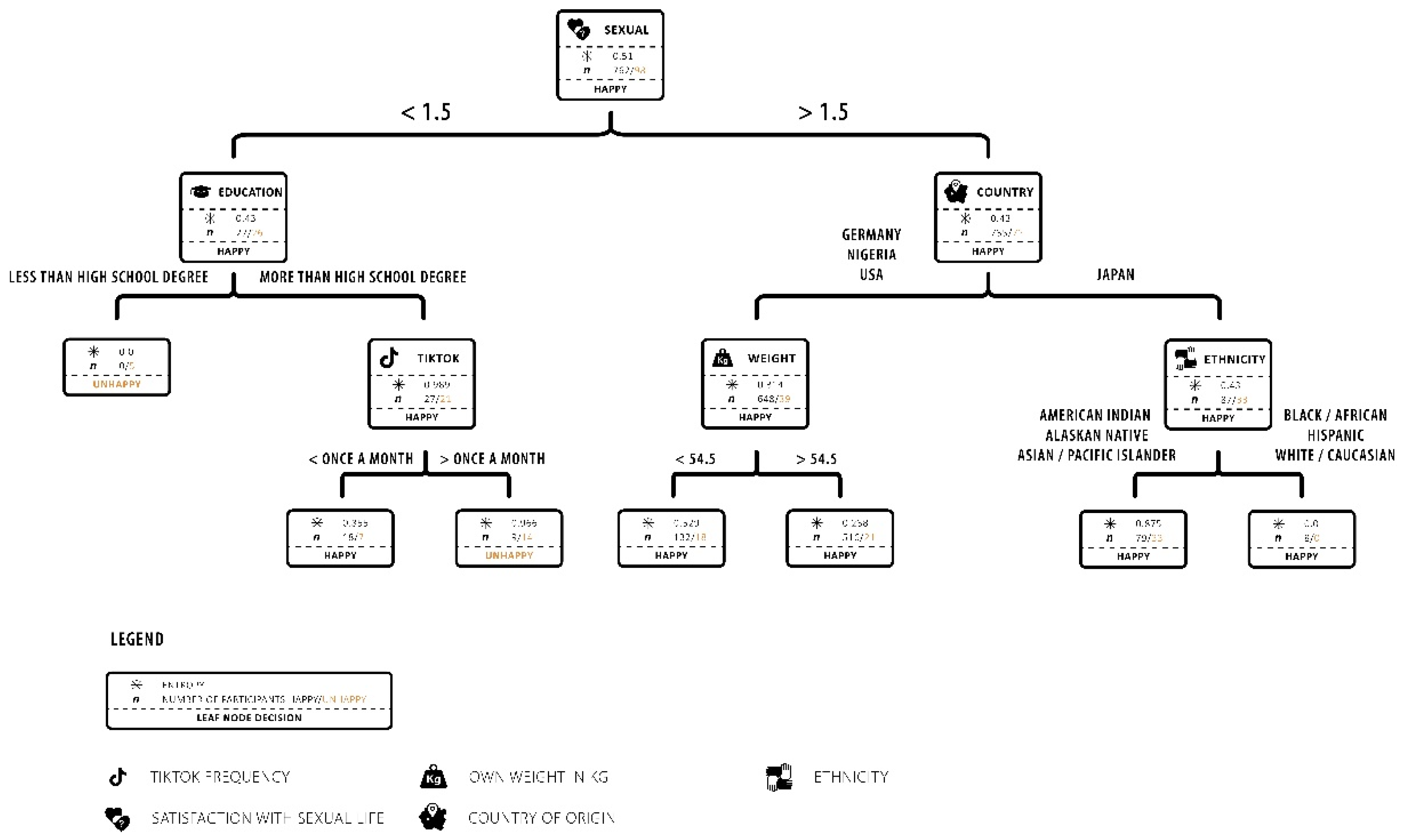

3.3. Identification of Major Factors Influencing the Perception of One’s Own Buttocks

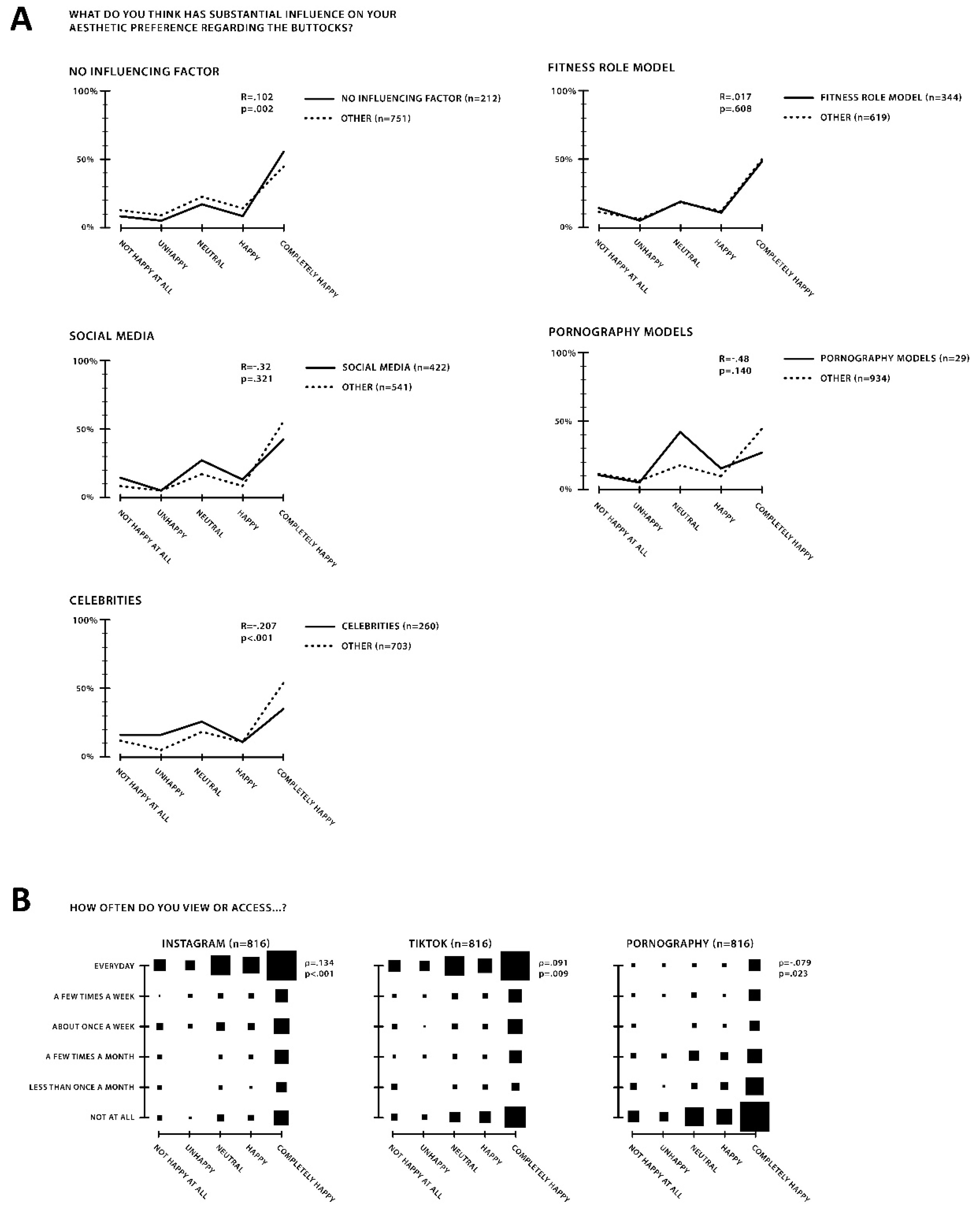

3.4. Social Media Was Identified as a Crucial Trigger for the Perception of Gluteal Esthetics in Females

3.5. Correlation of the Influencers’ WHR with the Participants’ Favored WHR

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Strengths of the Study

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frederick, D.A.; Daniels, E.A.; Bates, M.E.; Tylka, T.L. Exposure to thin-ideal media affect most, but not all, women: Results from the Perceived Effects of Media Exposure Scale and open-ended responses. Body Image 2017, 23, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keery, H.; van den Berg, P.; Thompson, J.K. An evaluation of the Tripartite Influence Model of body dissatisfaction and eating disturbance with adolescent girls. Body Image 2004, 1, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiggemann, M.; Polivy, J. Upward and Downward: Social Comparison Processing of Thin Idealized Media Images. Psychol. Women Q. 2010, 34, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, D.A.; Sandhu, G.; Scott, T.; Akbari, Y. Reducing the negative effects of media exposure on body image: Testing the effectiveness of subvertising and disclaimer labels. Body Image 2016, 17, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederick, D.A.; Lever, J.; Peplau, L.A. Interest in cosmetic surgery and body image: Views of men and women across the lifespan. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007, 120, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cash, T.F.; Thériault, J.; Annis, N.M. Body Image in an Interpersonal Context: Adult Attachment, Fear of Intimacy and Social Anxiety. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 23, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luff, G.M.; Gray, J.J. Complex messages regarding a thin ideal appearing in teenage girls’ magazines from 1956 to 2005. Body Image 2009, 6, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaznavi, J.; Taylor, L.D. Bones, body parts, and sex appeal: An analysis of #thinspiration images on popular social media. Body Image 2015, 14, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestos, M.; Smith-Merry, J.; Campbell, A. Representation of Women in Video Games: A Systematic Review of Literature in Consideration of Adult Female Wellbeing. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Jiang, C.; Chen, H. Associations between Chinese/Asian versus Western mass media influences and body image disturbances of young Chinese women. Body Image 2016, 17, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylka, T.L.; Russell, H.L.; Neal, A.A. Self-compassion as a moderator of thinness-related pressures’ associations with thin-ideal internalization and disordered eating. Eat. Behav. 2015, 17, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, Z.; Tiggemann, M. Attractive celebrity and peer images on Instagram: Effect on women’s mood and body image. Body Image 2016, 19, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McComb, S.E.; Mills, J.S. The effect of physical appearance perfectionism and social comparison to thin-, slim-thick-, and fit-ideal Instagram imagery on young women’s body image. Body Image 2022, 40, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, J.B.; Thomas, E.V.; Rogers, C.B.; Clark, V.N.; Hartsell, E.N.; Putz, D.Y. Fitspo at Every Size? A comparative content analysis of #curvyfit versus #curvyyoga Instagram images. Fat Stud. 2019, 8, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, D.E.; Sabik, N.J.; Ramsey, L.R. Ideal comparisons: Body ideals harm women’s body image through social comparison. Body Image 2019, 29, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahern, A.L.; Bennett, K.M.; Kelly, M.; Hetherington, M.M. A qualitative exploration of young women’s attitudes towards the thin ideal. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E.A.; Kluck, A.S.; Ramon, A.E.; Ruff, E.; Dario, J. The Curvy Ideal Silhouette Scale: Measuring Cultural Differences in the Body Shape Ideals of Young U.S. Women. Sex Roles 2021, 84, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, V.; Tovée, M.J. Female physical attractiveness in Britain and Malaysia: A cross-cultural study. Body Image 2005, 2, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, M.; Lee, C. Too fat, too thin: Understanding bias against overweight and underweight in an Australian female university student sample. Psychol. Health 2015, 30, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streeter, S. Waist-hip ratio and attractiveness New evidence and a critique of “a critical test”. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2003, 24, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Dixson, B.J.; Jessop, T.S.; Morgan, B.; Dixson, A.F. Cross-cultural consensus for waist–hip ratio and women’s attractiveness. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2010, 31, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovet, J. Evolutionary Theories and Men’s Preferences for Women’s Waist-to-Hip Ratio: Which Hypotheses Remain? A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassek, W.D.; Gaulin, S.J.C. Substantial but Misunderstood Human Sexual Dimorphism Results Mainly From Sexual Selection on Males and Natural Selection on Females. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 859931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokowski, P.; Sorokowska, A. Judgments of sexual attractiveness: A study of the Yali tribe in Papua. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2012, 41, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sorokowski, P.; Kościński, K.; Sorokowska, A.; Huanca, T. Preference for women’s body mass and waist-to-hip ratio in Tsimane’ men of the Bolivian Amazon: Biological and cultural determinants. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovet, J.; Lao, J.; Bartholomée, O.; Caldara, R.; Raymond, M. Mapping female bodily features of attractiveness. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlowe, F.W.; Berbesque, J.C.; Wood, B.; Crittenden, A.; Porter, C.; Mabulla, A. Honey, Hadza, hunter-gatherers, and human evolution. J. Hum. Evol. 2014, 71, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Swami, V. Perception of Female Buttocks and Breast Size in Profile. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2007, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlíček, J.; Třebický, V.; Valentova, J.V.; Kleisner, K.; Akoko, R.M.; Fialová, J.; Jash, R.; Kočnar, T.; Pereira, K.J.; Štěrbová, Z.; et al. Men’s preferences for women’s breast size and shape in four cultures. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2017, 38, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo, L.F.; Mireles-Rios, R.; Hurtado, A. Cultural, Media, and Peer Influences on Body Beauty Perceptions of Mexican American Adolescent Girls. J. Adolesc. Res. 2016, 31, 474–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, Y.; Ryan, E.; Agle, M.; Legaspi, M.; Toohey, R. The Role of Racial Identity in Responses to Thin Media Ideals. Commun. Res. 2009, 36, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, G.H.; Norwood, C.; Taylor, D.S.; Martinez, M.; McClain, S.; Jones, B.; Holman, A.; Chapman-Hilliard, C. Beauty and Body Image Concerns Among African American College Women. J. Black Psychol. 2015, 41, 540–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tijerina, J.D.; Morrison, S.D.; Nolan, I.T.; Parham, M.J.; Richardson, M.T.; Nazerali, R. Celebrity Influence Affecting Public Interest in Plastic Surgery Procedures: Google Trends Analysis. Aesth. Plast. Surg. 2019, 43, 1669–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mofid, M.M.; Teitelbaum, S.; Suissa, D.; Ramirez-Montañana, A.; Astarita, D.C.; Mendieta, C.; Singer, R. Report on Mortality from Gluteal Fat Grafting: Recommendations from the ASERF Task Force. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2017, 37, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohimi, A.A.; Olagoke, S.M.; Izza Wan Husin, W.N. White Beauty: The Moderating Role of Social Media Addiction on Social Comparison and Skin Tone Satisfaction. AJARR 2021, 15, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, R.R. #ModernBaartmans: Black Women’s Reimagining of Saartjie Baartman. J. Black Stud. 2021, 52, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, T.D.; Tiggemann, M. The role of perfectionism in body dissatisfaction. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComb, S.E.; Mills, J.S. Young women’s body image following upwards comparison to Instagram models: The role of physical appearance perfectionism and cognitive emotion regulation. Body Image 2021, 38, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J. In the eye of the beholder: Thin-ideal media affects some, but not most, viewers in a meta-analytic review of body dissatisfaction in women and men. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2013, 2, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamiya, Y.; Shimai, S.; Schaefer, L.M.; Thompson, J.K.; Shroff, H.; Sharma, R.; Ordaz, D.L. Psychometric properties and validation of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4) with a sample of Japanese adolescent girls. Body Image 2016, 19, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellitteri, M. Kawaii Aesthetics from Japan to Europe: Theory of the Japanese “Cute” and Transcultural Adoption of Its Styles in Italian and French Comics Production and Commodified Culture Goods. Arts 2018, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, K.; Giorgianni, F.E.; Danthinne, E.S.; Rodgers, R.F. Beauty ideals, social media, and body positivity: A qualitative investigation of influences on body image among young women in Japan. Body Image 2021, 38, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockhoff, M.; Mussap, A.J.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Mellor, D.; Skouteris, H.; McCabe, M.P.; Ricciardelli, L.A. Cultural differences in body dissatisfaction: Japanese adolescents compared with adolescents from China, Malaysia, Australia, Tonga, and Fiji. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 19, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazue, L.O. The contributions of media, body image concerns and locality to the perceived self-esteem of female Nigerian adolescents. Gend. Behav. 2014, 12, 6113–6124. [Google Scholar]

- Abimbola, M.O. The Impact of Advertising and Culture on the Transformation of Body Image in Nigeria; University of Central Lancashire: Preston, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wallner, C.; Dahlmann, V.; Montemurro, P.; Kümmel, S.; Reinisch, M.; Drysch, M.; Schmidt, S.V.; Reinkemeier, F.; Huber, J.; Wagner, J.M.; et al. The Search for the Ideal Female Breast: A Nationally Representative United-States-Census Study. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J. An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujols, Y.; Seal, B.N.; Meston, C.M. The association between sexual satisfaction and body image in women. J. Sex. Med. 2010, 7, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séjourné, N.; Got, F.; Solans, C.; Raynal, P. Body image, satisfaction with sexual life, self-esteem, and anxiodepressive symptoms: A comparative study between premenopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal women. J. Women Aging 2019, 31, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshari, P.; Houshyar, Z.; Javadifar, N.; Pourmotahari, F.; Jorfi, M. The Relationship Between Body Image and Sexual Function in Middle-Aged Women. Electron. Physician 2016, 8, 3302–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.C.; Vigfusdottir, T.H.; Lee, Y. Body Image and the Appearance Culture Among Adolescent Girls and Boys. J. Adolesc. Res. 2004, 19, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyal, K.; Te’eni-Harari, T. Explaining the Relationship Between Media Exposure and Early Adolescents’ Body Image Perceptions. J. Media Psychol. 2013, 25, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, C.; Vandenbosch, L. Adolescent girls’ Instagram and TikTok use: Examining relations with body image-related constructs over time using random intercept cross-lagged panel models. Body Image 2022, 41, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiphoo, A.N.; Vahedi, Z. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe-Calverley, E.; Grieve, R. Do the metrics matter? An experimental investigation of Instagram influencer effects on mood and body dissatisfaction. Body Image 2021, 36, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidekrueger, P.I.; Sinno, S.; Tanna, N.; Szpalski, C.; Juran, S.; Schmauss, D.; Ehrl, D.; Ng, R.; Ninkovic, M.; Broer, P.N. The Ideal Buttock Size: A Sociodemographic Morphometric Evaluation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 140, 20e–32e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, G.; Fussell, S.; Lampe, C.; Schraefel, M.; Hourcade, J.P.; Appert, C.; Wigdor, D. (Eds.) 2017 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Proceedings of the CHI ‘17: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, F.R.; Daskalova, N.; White, B. Comparing the Reliability of Amazon Mechanical Turk and Survey Monkey to Traditional Market Research Surveys. In 2017 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Proceedings of the CHI ‘17: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; Mark, G., Fussell, S., Lampe, C., Schraefel, M., Hourcade, J.P., Appert, C., Wigdor, D., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1092–1099. ISBN 9781450346566. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G.; Kronick, D.; Levendusky, M.; Meredith, M. The Majoritarian Threat to Liberal Democracy. J. Exp. Polit. Sci. 2022, 9, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.N.; Kleyman, K.S. The influence of Western body ideals on Kenyan, Kenyan American, and African Americans’ body image. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2020, 48, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Germany (n = 151) | Nigeria (n = 486) | USA (n = 179) | Japan (n = 144) | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Happy with one’s own buttocks? | 3.45 | 1.13 | 4.37 | 1.25 | 3.66 | 1.22 | 2.18 | 1.00 | 0.001 |

| Would you surgically change your buttocks? (%) | 23.8 | 8.2 | 63.1 | 4.3 | 0.001 | ||||

| Have you had an esthetic procedure done on your buttocks? (%) | 17.2 | 5.3 | 11.2 | 1.3 | 0.001 | ||||

| What part of the female body are you most attracted to? (%) | |||||||||

| Breast | 21.2 | 20.0 | 28.5 | 27.9 | 0.001 | ||||

| Buttocks | 19.9 | 34.4 | 57.0 | 5.4 | 0.001 | ||||

| Abdomen | 10.6 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.001 | ||||

| Legs | 8.6 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 23.1 | 0.001 | ||||

| Face | 39.7 | 38.6 | 14.5 | 40.8 | 0.001 | ||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||||

| Feature | Variable Feature Importance Score (a.u.) |

|---|---|

| Satisfaction with sex life | 0.405 |

| Country of origin | 0.353 |

| Weight | 0.096 |

| Level of education | 0.061 |

| TikTok frequency | 0.042 |

| Ethnicity | 0.042 |

| Germany | Nigeria | USA | Japan | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

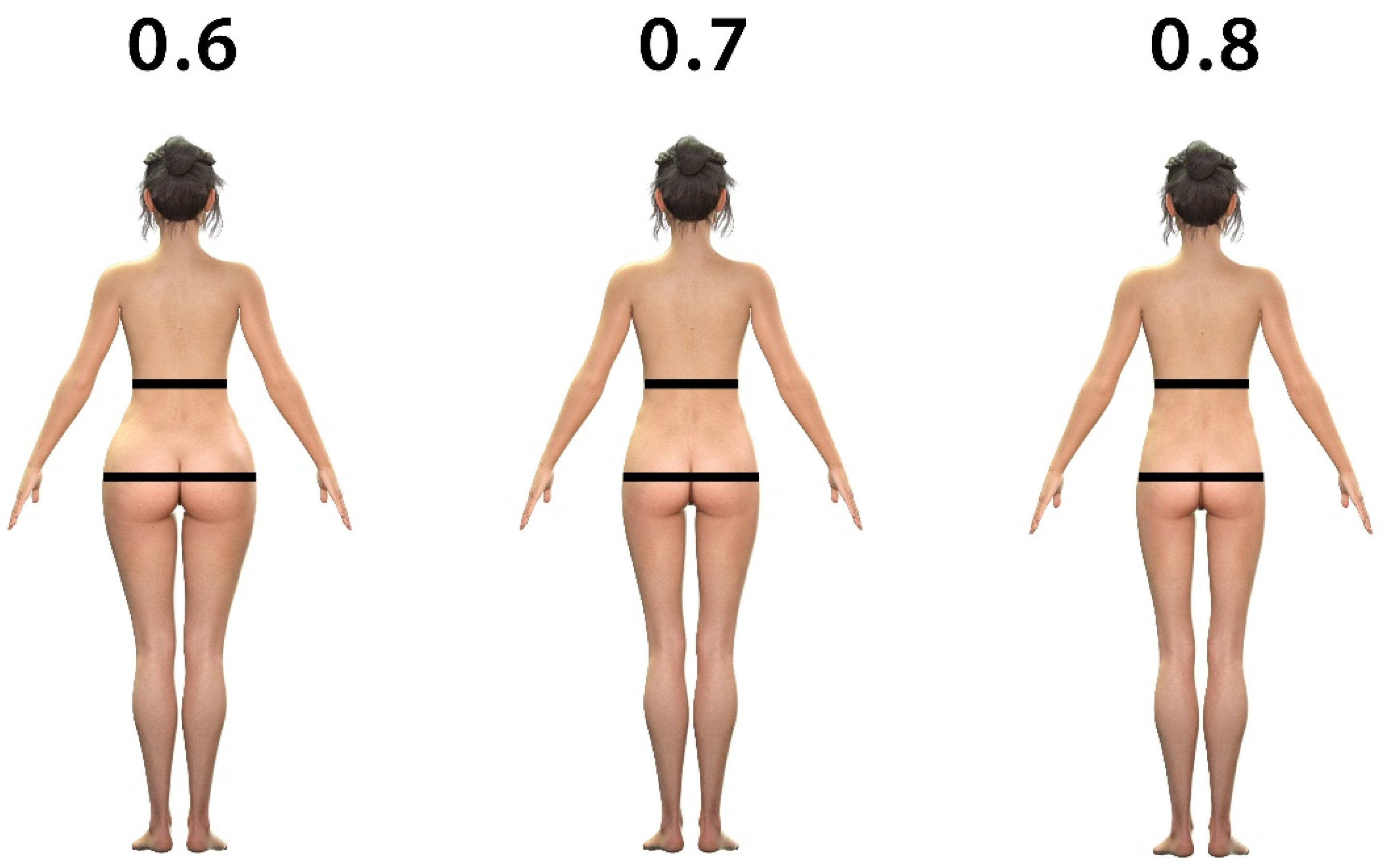

| Participants’ favored WHR (a.u.) | 0.650 (n = 275) | 0.641 (n = 1057) | 0.623 (n = 375) | 0.738 (n = 304) | 0.001 |

| WHR of fitness influencer (a.u.) | 0.656 (n = 25) | 0.641 (n = 11) | 0.636 (n = 49) | 0.685 (n = 17) | 0.001 |

| p-value | 0.651 | 0.984 | 0.147 | 0.004 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wallner, C.; Kruber, S.; Adebayo, S.O.; Ayandele, O.; Namatame, H.; Olonisakin, T.T.; O. Olapegba, P.; Sawamiya, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Yamamiya, Y.; et al. Interethnic Influencing Factors Regarding Buttocks Body Image in Women from Nigeria, Germany, USA and Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013212

Wallner C, Kruber S, Adebayo SO, Ayandele O, Namatame H, Olonisakin TT, O. Olapegba P, Sawamiya Y, Suzuki T, Yamamiya Y, et al. Interethnic Influencing Factors Regarding Buttocks Body Image in Women from Nigeria, Germany, USA and Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013212

Chicago/Turabian StyleWallner, Christoph, Svenja Kruber, Sulaiman Olanrewaju Adebayo, Olusola Ayandele, Hikari Namatame, Tosin Tunrayo Olonisakin, Peter O. Olapegba, Yoko Sawamiya, Tomohiro Suzuki, Yuko Yamamiya, and et al. 2022. "Interethnic Influencing Factors Regarding Buttocks Body Image in Women from Nigeria, Germany, USA and Japan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013212

APA StyleWallner, C., Kruber, S., Adebayo, S. O., Ayandele, O., Namatame, H., Olonisakin, T. T., O. Olapegba, P., Sawamiya, Y., Suzuki, T., Yamamiya, Y., Wagner, M. J., Drysch, M., Lehnhardt, M., & Behr, B. (2022). Interethnic Influencing Factors Regarding Buttocks Body Image in Women from Nigeria, Germany, USA and Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013212