Benefits of a Wearable Activity Tracker with Safety Features for Older Adults: An Intervention Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Benefits of WAT Use for Older Adults

1.2. Benefits of TC Use for Older Adults

1.3. Aims and Research Questions

- What is the effect of using ST on older adults’ motivation for PA?

- Which factors related to ST use affect PA levels among older adults?

- Which factors related to ST use affect the perceived usefulness of ST among older adults?

- What are the psychological outcomes of using ST among older adults?

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Design and Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Materials

2.4. Measures and Data Analysis

2.5. Methodological Rigur

2.6. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Motivation for Physical Activity and Physical Activity Level

“The solution has increased my motivation to be physically active.”(PU03, M, 71)

“I got insights into my activities, and the app motivates me to move more.”(PU15, F, 66)

“My mother doesn’t have a problem with falls. But the app’s step-counting and other daily activity-tracking features kept her motivated.”(SU02, F, daughter, 39)

“I tend to be a lazy person by nature. The sensor warns you that you haven’t walked enough and that you haven’t done enough for yourself that day. You realize that you need to take things seriously and that you need to take a little walk. From that point of view, this sensor is worth its weight in gold.”(PU06, F, 68)

“I did not perceive this device as a motivator for physical activity. I carried it around casually. No, I was carrying it around with me. I mean, I didn’t think it would make me achieve more, or that I would walk more. What was interesting for me was that it gave me information about my own activities.”(PU02, F, 73)

“Based on the results that the app has shown me, my daily activity level is consistently above average, according to the WHO. This is interesting and important for my confidence and encouragement to continue to be active.”(PU02, F, 73)

“I now have an overview of my activities, daily, weekly, and monthly … I am surprised that I am doing so many kilometers. I have insight into calories burned in all my activities, steps, and kilometers walked, and how many kilometers per hour I do on average.”(PU14, F, 62)

“When you go for a walk, you leave the clip on the table at home, or you put the cell phone on the tray in the car and forget about it, and before you even realize you don’t have the cell phone with you …”(PU06, F, 68)

“I have certain days when I go for a walk, and certain days when I don’t. In between, I was also sick, so I didn’t go for a walk. In the meantime, at the turn of the year, I walked quite a bit, but then I lost my sensor. So I looked for it, and it wasn’t there. But in the end, I found it. Anyway, these things happen.”(PU14, F, 62)

“And then came Christmas and New Year’s vacations. So we were at home and went for walks much less.”(PU07, F, 77)

“I am less active because I have health problems. That’s true. But I do exercise in the morning, every morning. And I make these 1000 movements. But the sensor does not detect these movements.”(PU06, F, 68)

“In the past, there were no problems. But lately, there have been problems with the sensor. When I leave the house, I put it in the usual place in my pocket, always in the same place. Before it recorded all my steps, now hardly any steps on the whole 12-km route.”(PU07, F, 77)

“I’ve been in Pokljuka for two weeks now. And I haven’t used it at all.”(PU13, M, 64)

“I mean, it makes you think even more about the importance of being physically active. Definitely a positive influence. // I mean, it was interesting data anyway. I was measuring this activity, not that I was now increasing physical activity by I don’t know how much. I was just interested in how much I actually did.”(PU12, F, 70)

“At first I thought it might be a bit distracting, that it would be a bit of a commitment, but then after a week, or I would say 14 days, I just really liked it so I was happy to track my steps, calories, and then kilometers every day.”(PU15, F, 66)

3.2. Perceived Usefulness of ST

“It suits me. To me, it’s like just put it in your pocket, attach it somewhere on your clothing … I mean, this sensor is really, I have to say, really cool. It’s really very convenient”.(PU13, M, 64)

“It is useful because my father knows how to use such technology”.(SU09, F, daughter, 43)

“It was useful because it encouraged me to move …”(PU03, M, 71)

“It’s useful for checking steps, calories burned, and how many minutes you have been active.”(SU01, F, daughter, 48)

“All of the activity monitoring features that were included in the solution were useful, if not otherwise, for her to monitor her physical activity a little more.”(SU01, F, daughter, 48)

“I did not fall during the intervention, and I’m still in pretty good shape. So, it gives me a greater sense of safety and is a great motivator to keep moving.”(PU12, F, 70)

“I would say the most important thing is that I can actually tell someone that I am in trouble in the simplest way. At the touch of a button hanging around my neck, not crawling to the phone to look for a phone that I forgot I had, that I do not know where it is.”(PU08, M, 69)

“Even when I go for a long walk alone, I feel safe because I am connected to my daughter, who would get a message if I fell. You can move more freely because you know that if you have a problem, you are connected to someone who will help you.”(PU16, F, 62)

“For me, it was nice to measure how many steps I take to see how active I am.”(PU04, F, 62)

“You have to have your phone with you at all times, which is more difficult if you live in a house. A fall can happen if the phone is not within the reach of the device that detects the fall.”(SU12, F, partner, 69)

“I am not used to having my cell phone with me all the time. That’s what bothered me the most, that I always have to have my cell phone with me.”(PU02, F, 73)

“Inside the house I have to constantly check the connection, outdoors, while walking, sometimes it works, sometimes it shuts down under the same conditions. I cannot imagine what it would be like if I really needed it when I fall.”(PU07, F, 77)

“The solution is not useful because there are false alarms, and it does not provide a sense of safety.”(PU12, F, 70)

“False alarms that a person has fallen are too frequent, so there is a risk of not responding to the alarm because it is just another false alarm.”(SU12, M, partner, 69)

“It was useful because it encouraged me to improve. I reviewed all my physical activity results to see what I could do better.”(PU08, M, 69, no previous experiences with WAT)

“Continued use would be an unnecessary expense for me for now. I have a sports tracker for activity tracking that meets my needs. The device would be useful if either of us were bedridden.”(PU03, M, 71, experiences with WAT)

“You see, if the solution remains as it is, I will not buy it. I already have a smartwatch that tells me the exact steps that I walk. Maybe one day, I will buy the SOS phone.”(PU07, F, 77, experiences with WAT)

“Well, I think that maybe I’m a little bit too young, too active in terms of what the device can do, for it to really help me and encourage me, or for me to feel like it would really protect me.”(PU01, F, 70)

“This solution is less useful for older adults who do not own smartphones.”(SU09, F, daughter, 43)

3.3. Psychological Outcomes of ST Use

“When you walk alone, you have a phone with you, but you never know if you would be able to make a call, do you? With this solution, my safety has definitely increased.”(PU 01, F, 70)

“Even when I go for a long walk by myself, I feel safe because I am connected to my daughter, who gets a message if I fall. You can move more freely because you know that if you have a problem, you are connected to someone who will help you.”(PU14, F, 62)

“For a person walking alone on forest trails, it’s worth a lot to know where they are if they need help.”(PU13, M, 64)

“We both have a better feeling; especially if she might actually need help, she knows that someone will be informed immediately.”(SU15, F, daughter, 43)

“We both have a better sense of safety, especially when she really needs help, and she has a better sense that someone will be notified right away.”(SU13, M, son, 29)

“Even if my mom pressed the button “by mistake/for fun”, I always reacted with great interest, as if it was a serious case. Great, because I get a text message with the location.”(SU08, M, son, 43)

“For me, the clip is a device that makes me constantly afraid of losing the connection.”(PU06, F, 68)

“I am not used to having my phone with me all the time. That’s what bothered me the most that I always have to have my phone with me.”(PU02, F, 73)

“It brings me stress—I have to take care of both devices to keep them charged. It’s an extra worry for me. Also, it’s another stressor to have the phone with you or make sure it’s nearby.”(PU06, F, 68)

“I was walking around, and I was a little afraid of losing the sensor by accident … That was what I was most afraid of.”(PU13, M, 64)

“I go a few steps from one room to another, like the kitchen, and it gets disconnected. In the beginning, I had to keep turning it on, and that was nerve-wracking, I have to admit.”(PU13, F, 77)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation Noncommunicable Diseases Fact Sheet. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs355/en/ (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Uei, S.-L.; Kuo, Y.-M.; Tsai, C.-H.; Kuo, Y.-L. An Exploration of Intent to Use Telehealth at Home for Patients with Chronic Diseases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishchyk, A.; Chen, W.; Pripp, A.H.; Bergland, A. The Effect of Mixed Reality Technologies for Falls Prevention Among Older Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Aging 2021, 4, e27972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, L.D.; Robertson, M.C.; Gillespie, W.J.; Sherrington, C.; Gates, S.; Clemson, L.M.; Lamb, S.E. Interventions for Preventing Falls in Older People Living in the Community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 9, CD007146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenhagen, M.; Ekström, H.; Nordell, E.; Elmståhl, S. Falls in the General Elderly Population: A 3- and 6-Year Prospective Study of Risk Factors Using Data from the Longitudinal Population Study “Good Ageing in Skane”. BMC Geriatr. 2013, 13, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Harmer, P. Protocol for Disseminating an Evidence-Based Fall Prevention Program in Community Senior Centers: Evaluation of Translatability and Public Health Impact via a Single Group Pre-Post Study. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luk, J.K.H.; Chan, T.; Chan, D.K.Y. Falls Prevention in the Elderly: Translating Evidence into Practice. Hong Kong Med. J. 2015, 21, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.; Atique, M.M.U.; Mishra, R.; Najafi, B. Association between Fall History and Gait, Balance, Physical Activity, Depression, Fear of Falling, and Motor Capacity: A 6-Month Follow-Up Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Bao, D.; Zhou, J. Comparison between the Effects of Exergame Intervention and Traditional Physical Training on Improving Balance and Fall Prevention in Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. JNER 2021, 18, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Franssen, W.M.A.; Franssen, G.H.L.M.; Spaas, J.; Solmi, F.; Eijnde, B.O. Can Consumer Wearable Activity Tracker-Based Interventions Improve Physical Activity and Cardiometabolic Health in Patients with Chronic Diseases? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Effect of Physical Inactivity on Major Non-Communicable Diseases Worldwide: An Analysis of Burden of Disease and Life Expectancy. Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurocarers. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) for Carers; European Association Working for Carers—Eurocarers: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Gollamudi, S.S.; Steinhubl, S. Digital Technology to Enable Aging in Place. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 88, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvalič-Touzery, S.; Smole-Orehek, K.; Dolničar, V. Informal Caregivers’ Perceptions of Self-Efficacy and Subjective Well-Being When Using Telecare in the Home Environment: A Qualitative Study. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsen, C.; Ludvigsen, M.S.; Moe, C.E.; Haraldstad, K.; Thygesen, E. Experiences of the Home-Dwelling Elderly in the Use of Telecare in Home Care Services: A Qualitative Systematic Review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2017, 15, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, T.; Durick, J.; Brereton, M.; Vetere, F.; Howard, S.; Nansen, B. Knowing Our Users: Scoping Interviews in Design Research with Ageing Participants. In Proceedings of the 24th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 26–30 November 2012; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 517–520. [Google Scholar]

- Government Office for Science. Future of an Ageing Population; Government Office for Science, Foresight: London, UK, 2016.

- Hvalič Touzery, S.; Dolničar, V. Attitudes towards Smart Technologies among Older People and Their Informal Carers in Slovenia. In Zdravje Starostnikov, Health of the Elderly; Petelin, A., Ed.; University of Primorska Press: Koper, Slovenia, 2021; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Khosravi, P.; Rezvani, A.; Wiewiora, A. The Impact of Technology on Older Adults’ Social Isolation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagode, M.; Črnak Meglič, A.; Dremelj, P.; Dolničar, V.; Hvalič Touzery, S.; Istenič, A.; Kobal Tomc, B.; Lebar, L.; Majcen, B.; Natek, I.; et al. Dolgotrajna Oskrba: Izziv in Priložnost Za Boljši Jutri; Nacionalni Inštitut za Javno Zdravje: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, C.; Dorner, T.E. Review Article: Information Technologies for Active and Assisted Living—Influences to the Quality of Life of an Ageing Society. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2017, 100, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbrig, I.; Hvalič Touzery, S.; Piazolo, F.; Sturm, N.; van der Weegen, S. The I-EvAALution RCT: Rationale, Methods and First Results of the Pre-Tests. Gerontechnology 2020, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smole-Orehek, K.; Hvalič-Touzery, S.; Petrovčič, A.; Dolnicar, V.; Debevc, M.; Kozuh, I. Psychological Outcomes of ECare Technologies Use for Informal Carers: A Scoping Study. Gerontechnology 2019, 18, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, G.; Jarrahi, M.H.; Fei, Y.; Karami, A.; Gafinowitz, N.; Byun, A.; Lu, X. Wearable Activity Trackers, Accuracy, Adoption, Acceptance and Health Impact: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 93, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravata, D.M.; Smith-Spangler, C.; Sundaram, V.; Gienger, A.L.; Lin, N.; Lewis, R.; Stave, C.D.; Olkin, I.; Sirard, J.R. Using Pedometers to Increase Physical Activity and Improve Health: A Systematic Review. JAMA 2007, 298, 2296–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodkinson, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Adeniji, C.; van Marwijk, H.; McMillian, B.; Bower, P.; Panagioti, M. Interventions Using Wearable Physical Activity Trackers among Adults with Cardiometabolic Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2116382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.Y.W.; Kwan, R.Y.C.; Yin, Y.-H.; Lee, P.H.; Siu, J.Y.; Bai, X. Enhancing the Physical Activity Levels of Frail Older Adults with a Wearable Activity Tracker-Based Exercise Intervention: A Pilot Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.; Auinger, A.; Riedl, R.; Kindermann, H.; Helfert, M.; Ocenasek, H. Digitally Enhanced Recovery: Investigating the Use of Digital Self-Tracking for Monitoring Leisure Time Physical Activity of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Patients Undergoing Cardiac Rehabilitation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, T.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Blake, H.; Crozier, A.J.; Dankiw, K.; Dumuid, D.; Kasai, D.; O’Connor, E.; Virgara, R.; et al. Effectiveness of Wearable Activity Trackers to Increase Physical Activity and Improve Health: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Lancet Digit. Health 2022, 4, e615–e626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickwood, K.-J.; Williams, A.D.; Watson, G.; O’Brien, J. Older Adults’ Experiences of Using a Wearable Activity Tracker with Health Professional Feedback over a 12-Month Randomised Controlled Trial. Digit. Health 2020, 6, 2055207620921678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwek, L.; Ellis, D.A.; Andrews, S.; Joinson, A. The Rise of Consumer Health Wearables: Promises and Barriers. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.; Gross, A.; Brinkman, C.; Pope, R.; Allen, K.; Hastings, S.; Bogen, B.E.; Goode, A.P. The Impact of Wearable Motion Sensing Technology on Physical Activity in Older Adults. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 112, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, R.T.; Christensen, J.; Juhl, C.B.; Andersen, H.B.; Langberg, H. Physical Activity Monitors to Enhance Amount of Physical Activity in Older Adults—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, J.S.; Sherrington, C.; Zheng, E.R.Y.; Franco, M.R.; Tiedemann, A. Effect of Interventions Using Physical Activity Trackers on Physical Activity in People Aged 60 Years and over: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.; Chiatti, C.; Fry, G.; Hanson, E.; Magnusson, L.; Socci, M.; Stückler, A.; Széman, Z.; Barbabella, F.; Hoffmann, F.; et al. The CARICT Project-ICT-Based Solutions for Caregivers: Assessing Their Impact on the Sustainability of Long-Term Care in an Ageing Europe. Analysis and Mapping of 52 ICT-Based Initiatives for Caregivers; Deliverable 2.3; European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research: Vienna, Austria, 2011; Available online: http://lnu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A814867&dswid=5460 (accessed on 1 May 2016).

- Vargemidis, D.; Gerling, K.; Abeele, V.V.; Geurts, L.; Spiel, K. Irrelevant Gadgets or a Source of Worry: Exploring Wearable Activity Trackers with Older Adults. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 2021, 14, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Giordani, B.; Margulis, A.; Chen, W. Efficacy and Acceptability of Using Wearable Activity Trackers in Older Adults Living in Retirement Communities: A Mixed Method Study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.; Ophoff, J. Investigating Adoption Factors of Wearable Technology in Health and Fitnes. In Proceedings of the 2018 Open Innovations Conference (OI), Johannesburg, South Africa, 3–5 October 2018; pp. 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Peng, W.; Kononova, A.; Bowen, M.; Cotten, S.R. Factors Associated with Older Adults’ Long-Term Use of Wearable Activity Trackers. Telemed. E-Health 2020, 26, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kononova, A.; Li, L.; Kamp, K.; Bowen, M.; Rikard, R.V.; Cotten, S.; Peng, W. The Use of Wearable Activity Trackers Among Older Adults: Focus Group Study of Tracker Perceptions, Motivators, and Barriers in the Maintenance Stage of Behavior Change. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e9832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermsen, S.; Moons, J.; Kerkhof, P.; Wiekens, C.; Groot, M.D. Determinants for Sustained Use of an Activity Tracker: Observational Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017, 5, e7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel, K.D.S.; Lewin, G.; Burton, E.; Howat, P.; Boldy, D.; Toye, C. Personal Emergency Alarms: Do Health Outcomes Differ for Purchasers and Nonpurchasers? Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2017, 36, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsen, C.; Moe, C.E.; Haraldstad, K.; Thygesen, E. Caring by Telecare? A Hermeneutic Study of Experiences among Older Adults and Their Family Caregivers. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1300–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, T.B.; Storm, M.; Holm, A.L. Safety for Older Adults Using Telecare: Perceptions of Homecare Professionals. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvalič-Touzery, S.; Smole-Orehek, K.; Dolničar, V. Exploring Reciprocity in Perceptions on Telecare within the Informal Carer–Care Receiver Dyad. Teor. Praksa 2021, 58, 840–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavčič, M.; Petrovčič, A.; Dolničar, V. Model of Acceptance and Use of Market-Ready Home-Based e-Care Services: A Qualitative Study with Care Receivers and Informal Caregivers. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebar, L.; Hvalič-Touzery, S.; Natek, I.; Dolničar, V. Perception of the Use of Assistive Technologies. In Long-Term Care—A Challenge and an Opportunity for a Better Tomorrow. Evaluation of Pilot Projects in the Field of Long-Term Care; Nagode, M., Kobal Straus, K., Eds.; Ministry of Health of the Republic of Slovenia: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2022; pp. 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, P.A. Exploring Older Adults’ Perceptions of the Utility and Ease of Use of Personal Emergency Response Systemsof Personal Emergency Response System. Doctoral Dissertation, The City University of New York, New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chaparro, J.D.; Ruiz, J.F.-B.; Romero, M.J.S.; Peño, C.B.; Irurtia, L.U.; Perea, M.G.; Garcia, X.D.T.; Molina, F.J.V.; Grigoleit, S.; Lopez, J.C. The SHAPES Smart Mirror Approach for Independent Living, Healthy and Active Ageing. Sensors 2021, 21, 7938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, A.D.; McGregor, J.C.; Perencevich, E.N.; Furuno, J.P.; Zhu, J.; Peterson, D.E.; Finkelstein, J. The Use and Interpretation of Quasi-Experimental Studies in Medical Informatics. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2006, 13, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.E.; Grove, A.L.; Clarke, A. Pillar Integration Process: A Joint Display Technique to Integrate Data in Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2019, 13, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gociety Solutions, BV. Available online: https://www.goliveclip.eu/solutions/goliveclip/ (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Dolničar, V.; Berzelak, N.; Hvalič-Touzery, S. Dataset for: Factors Impacting Intention to Use Smart Technology Enabled Care Services among Family Carers of Older People in the Context of Long-Distance Care (J5-1785). PsychArchives 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevodnik, K.; Hvalič-Touzery, S.; Dolničar, V.; Škafar, M.; Petrovčič, A. The importance of user experience for psychosocial impacts of telemonitoring system utilization; Elektronski vir:: COBISS+. Gerontechnology 2020, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Blasio, A.; Izzicupo, P.; Di Donato, F.; Mazzocco, C. Automatic Report of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire IPAQ 2020. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/scoring-protocol (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Hurtig-Wennlöf, A.; Hagströmer, M.; Olsson, L.A. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire Modified for the Elderly: Aspects of Validity and Feasibility. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The IPAQ group. Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). 2015. Available online: http://www.ipaq.ki.se/ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Delaney, S.; Meyer, I.; Muller, S. The ECare Client Impact Survey (ECCIS)—Developing a New Tool for Assessing Client Impacts of Telehealthcare. Int. J. Integr. Care 2013, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, C.; Demers, L.; Gélinas, I.; Routhier, F.; Mortenson, W.B.; Miller, W.C. Reliability and Validity of the Telephone Administration of the Wheelchair Outcome Measure (WhOM) for Middle-Aged and Older Users of Power Mobility Devices. J. Rehabil. Med. 2010, 42, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, H.; Jutai, J. Measuring the Psychosocial Impact of Assistive Devices: The PIADS. Can. J. Rehabil. 1996, 9, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, P.; Jepson, J. The Search for a Suitable Outcome Measure for Use in Evaluating the Outcome of Provision of an Environmental Control System. J. Assist. Technol. 2012, 6, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4462-7142-1. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; SAGE: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-84787-581-5. [Google Scholar]

- Creaser, A.V.; Hall, J.; Costa, S.; Bingham, D.D.; Clemes, S.A. Exploring Families’ Acceptance of Wearable Activity Trackers: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon-Woods, M.; Shaw, R.L.; Agarwal, S.; Smith, J.A. The Problem of Appraising Qualitative Research. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2004, 13, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, L. Validity, Reliability, and Generalizability in Qualitative Research. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for Ensuring Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research Projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, J.; Hunter, A. Multimethod Research: A Synthesis of Styles; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Forero, R.; Nahidi, S.; De Costa, J.; Mohsin, M.; Fitzgerald, G.; Gibson, N.; McCarthy, S.; Aboagye-Sarfo, P. Application of Four-Dimension Criteria to Assess Rigour of Qualitative Research in Emergency Medicine. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, L.I.; Jansen, C.-P.; Depenbusch, J.; Gabrian, M.; Sieverding, M.; Wahl, H.-W. Using Wearables to Promote Physical Activity in Old Age. Z. Gerontol. Geriat. 2022, 55, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgers, N.D.; Timperio, A.; Brown, H.; Ball, K.; Macfarlane, S.; Lai, S.K.; Richards, K.; Mackintosh, K.A.; McNarry, M.A.; Foster, M.; et al. Wearable Activity Tracker Use among Australian Adolescents: Usability and Acceptability Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, K.; Giangregorio, L.; Schneider, E.; Chilana, P.; Li, M.; Grindrod, K. Acceptance of Commercially Available Wearable Activity Trackers among Adults Aged over 50 and with Chronic Illness: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016, 4, e4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Hadgraft, N.T.; Moore, M.M.; Rosenberg, D.E.; Lynch, C.; Reeves, M.M.; Lynch, B.M. A Qualitative Evaluation of Breast Cancer Survivors’ Acceptance of and Preferences for Consumer Wearable Technology Activity Trackers. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 3375–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, A.; Kim, B.; Nguyen, O.; Stolee, P.; Tung, J.; Lee, J. User Acceptance of Wrist-Worn Activity Trackers among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Mixed Method Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017, 5, e173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, A.; Frechette, L.; Miller, D.; Miller, E.; Friel, C.; Van Arsdale, A.; Lin, J.; Shankar, V.; Kuo, D.Y.S.; Nevadunsky, N.S. Acceptability and Feasibility of a Fitbit Physical Activity Monitor for Endometrial Cancer Survivors. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 149, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moy, M.L.; Martinez, C.H.; Kadri, R.; Roman, P.; Holleman, R.G.; Kim, H.M.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Cohen, M.D.; Goodrich, D.E.; Giardino, N.D.; et al. Long-Term Effects of an Internet-Mediated Pedometer-Based Walking Program for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmich, J.; Mandrusiak, A.; Russell, T.; Smith, S.; Hartley, N. Perspectives of Older Adults with Chronic Disease on the Use of Wearable Technology and Video Games for Physical Activity. Digit. Health 2021, 7, 20552076211019900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedesco, S.; Barton, J.; O’Flynn, B. A Review of Activity Trackers for Senior Citizens: Research Perspectives, Commercial Landscape and the Role of the Insurance Industry. Sensors 2017, 17, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, A.M.; Kadylak, T.; Cotten, S.R. Correlation between Socio-Demographic Factors and Adoption and Use of Wearable Activity Trackers in Online American Older Adults. Educ. Gerontol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehn, M.; Eriksson, L.C.; Åkerberg, N.; Johansson, A.-C. Activity Monitors as Support for Older Persons’ Physical Activity in Daily Life: Qualitative Study of the Users’ Experiences. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolničar, V.; Petrovčič, A.; Šetinc, M.; Košir, I.; Kavčič, M. Understanding Acceptance Factors for Using E-Care Systems and Devices: Insights from a Mixed-Method Intervention Study in Slovenia. In Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population: Applications, Services and Contexts: Third International Conference, ITAP 2017, Held as Part of HCI International 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–14 July 2017, Proceedings, Part 2, (Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNCS), 10298); Zhou, J., Salvendy, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 362–377. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, B.; Aplin, T.; de Jonge, D.; Goyne, M. Tracking down a Solution: Exploring the Acceptability and Value of Wearable GPS Devices for Older Persons, Individuals with a Disability and Their Support Persons. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2017, 12, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verloo, H.; Kampel, T.; Vidal, N.; Pereira, F. Perceptions About Technologies That Help Community-Dwelling Older Adults Remain at Home: Qualitative Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaschinski, C.; Ben Allouch, S. Listening to the Ones Who Care: Exploring the Perceptions of Informal Caregivers towards Ambient Assisted Living Applications. J. Ambient Intell. Hum. Comput. 2019, 10, 761–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvalič-Touzery, S.; Dolničar, V.; Prevodnik, K. Factors Influencing Informal Carers’ Acceptance of Assistive Telecare Systems in the Pre- and Post-Implementation Phase: A Scoping Study. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e1484–e1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCambridge, J.; Witton, J.; Elbourne, D.R. Systematic Review of the Hawthorne Effect: New Concepts Are Needed to Study Research Participation Effects. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.-C. Exploring the Acceptance of Telecare among Senior Citizens: An Application of Back-Propagation Network. Telemed. e-Health 2011, 17, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n = 22) | Completers (n = 13) | Drop-Outs (n = 9) | |

| Primary users | |||

| Age (years), M 1 (SD) 2 (min–max) | 68.95 (4.0) (62–77) | 68.08 (4.5) (62–77) | 70.22 (2.9) (67–75) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 5 (22.7%) | 4 (30.8%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| Female | 17 (77.3%) | 9 (69.2%) | 8 (88.9%) |

| Education level, n (%) | |||

| Two- or three-year vocational school | 2 (9.1%) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) |

| Four-year secondary school, high school | 7 (31.8%) | 2 (15.4%) | 5 (55.6%) |

| Higher education | 4 (18.2%) | 4 (30.8%) | 0 |

| College, university or academy or more | 9 (40.9%) | 7 (53.8%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| Health, n (%) | |||

| Very good | 1 (4.5%) | 0 | 1 (11.1%) |

| Good | 14 (63.6%) | 10 (76.9%) | 4 (44.4%) |

| Fair | 6 (27.3%) | 2 (15.4%) | 4 (44.4%) |

| Poor | 1 (4.5%) | 1 (7.7%) | 0 |

| Intensity of PA—(MET3—minutes/week) (n = 20) 4 | |||

| High, n (%), M (SD) | 12 (54.5%), 10,019.3 (5443.6) | 8 (61.5%), 10,503.7 (6348.8) | 4 (57.1%), 7597.7 (3157.0) |

| Moderate, n (%), M (SD) | 7 (31.8%), 1592.3 (727.0) | 4 (30.8%), 1081 (297.3) | 3 (42.9%), 2274 (354.9) |

| Low, n (%), M (SD) | 1 (4.5%), 558.0 (0) | 1 (7.7%), 558.0 (0) | 0 |

| The ability to use a smart phone, n (%) | |||

| Very good | 4 (18.2%) | 2 (15.4%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| Pretty good | 9 (40.9%) | 6 (46.2%) | 3 (33.3%) |

| Neither good nor bad | 9 (40.9%) | 5 (38.5%) | 4 (44.4%) |

| Type of technology adopter | |||

| Early adopters 5 | 4 (18.2%) | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| Late adopters 6 | 18 (81.8%) | 10 (76.9%) | 8 (88.9%) |

| Family relation to the secondary user, n (%) | |||

| Parent | 14 (63.6%) | 10 (76.9%) | 4 (44.4%) |

| Partner | 4 (18.2%) | 2 (15.4%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| Other | 4 (18.2%) | 1 (7.7%) | 3 (33.3%) |

| The average days in the study, M 1 (SD) 2 | 98.5 7 (41.4) | 125.9 (3.7) | 62.9 8 (6.1) |

| Total (n = 22) | Completers (n = 13) | Drop-outs (n = 9) | |

| Secondary users | |||

| Age (years), M 1 (SD) 2 | 46.83 (14.7) | 42.2 (9.5) | 58.8 (17.5) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 12 (54.5%) | 7 (53.8%) | 5 (55.6%) |

| Female | 10 (45.5%) | 6 (46.2%) | 4 (44.4%) |

| Education level, n (%) | |||

| Finished primary school | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 1 (20%) |

| Upper secondary vocational or general education | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 1 (20%) |

| Higher education | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 1 (20%) |

| College, university, academy or more | 15 (83.3%) | 13 (100%) | 2 (40%) |

| Input | Output | Purpose | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TC Features | |||

| Self-triggering alarm button | Triggering alarm by pressing the button | Sending an alert to the enlisted emergency contacts | Real-time notification in case of emergency |

| Automated fall detection | Detected falling incident | Sending an alert to the enlisted emergency contacts | Fall detection; real-time notification in case of potential falling incident |

| Fall risk measurement | Personal data (age, weight, height) and recorded data (walking asymmetry, walking speed, number of steps, distance walked) | Notification on user’s smartphone and alert sent to the enlisted emergency contacts | Assessment of fall risk on a scale from 1 to 10; historical trending analysis and informing when the risk of a falling incident goes up |

| WAT Features | |||

| Goal setting | Entering goals regarding the activity (WHO recommendation—at least 150 min of moderate physical activity per week OR daily steps goal OR daily calories burned goal) | Goals attainment (virtual medals) | Motivation to become more active or to reach certain specific goals |

| Activity tracker | Personal data (age, weight, height), integrated sensors | Number of steps, number of calories burned, total time of activity, average speed of movement, distance walked, MET (metabolic equivalent)—value of the activity | Clear overview of all collected information on user’s physical activity |

| Quantitative Data | Quantitative Categories | Pillar | Qualitative Categories (Themes Derived from the Thematic Analysis) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M2 and M4 PU questionnaire Motivation to engage in PA due to the use of the solution M2: M = 4.2 (SD = 0.7); M4: M = 4.0 (SD = 0.7) Scale: 1 = decreased a lot … 5 = increased a lot | PUs’ motivation for PA | Pillar 1. The use of ST as a motivator for PA | Interview STs as a PA motivator but not for all PU |

| Open-ended questions (M2 and M4 SU questionnaire) According to some SUs, the solution increased the motivation of their older relatives or family members for PA | |||

| Open-ended questions (M2 and M4 PU questionnaire) The solution increased the motivation for PA among some PUs. | |||

| No corresponding quantitative data | n/a | Interview Increased motivation for PA due to ST use expressed more by sexagenarians | |

| M2 and M4 PU questionnaire Enjoyment with the ST M2: M = 3.8 (SD = 0.9); M4: M = 3.5 (1.3) ST usage being pleasant M2: M = 3.7 (SD = 0.9); M4: M = 3.8 (SD = 0.9) Scale: 1 = decreased a lot … 5 = increased a lot | Intrinsic motivation brought feelings of enjoyment | Interview Prevalence of intrinsic motivation to use ST among PUs (feelings of enjoyment and accomplishment) | |

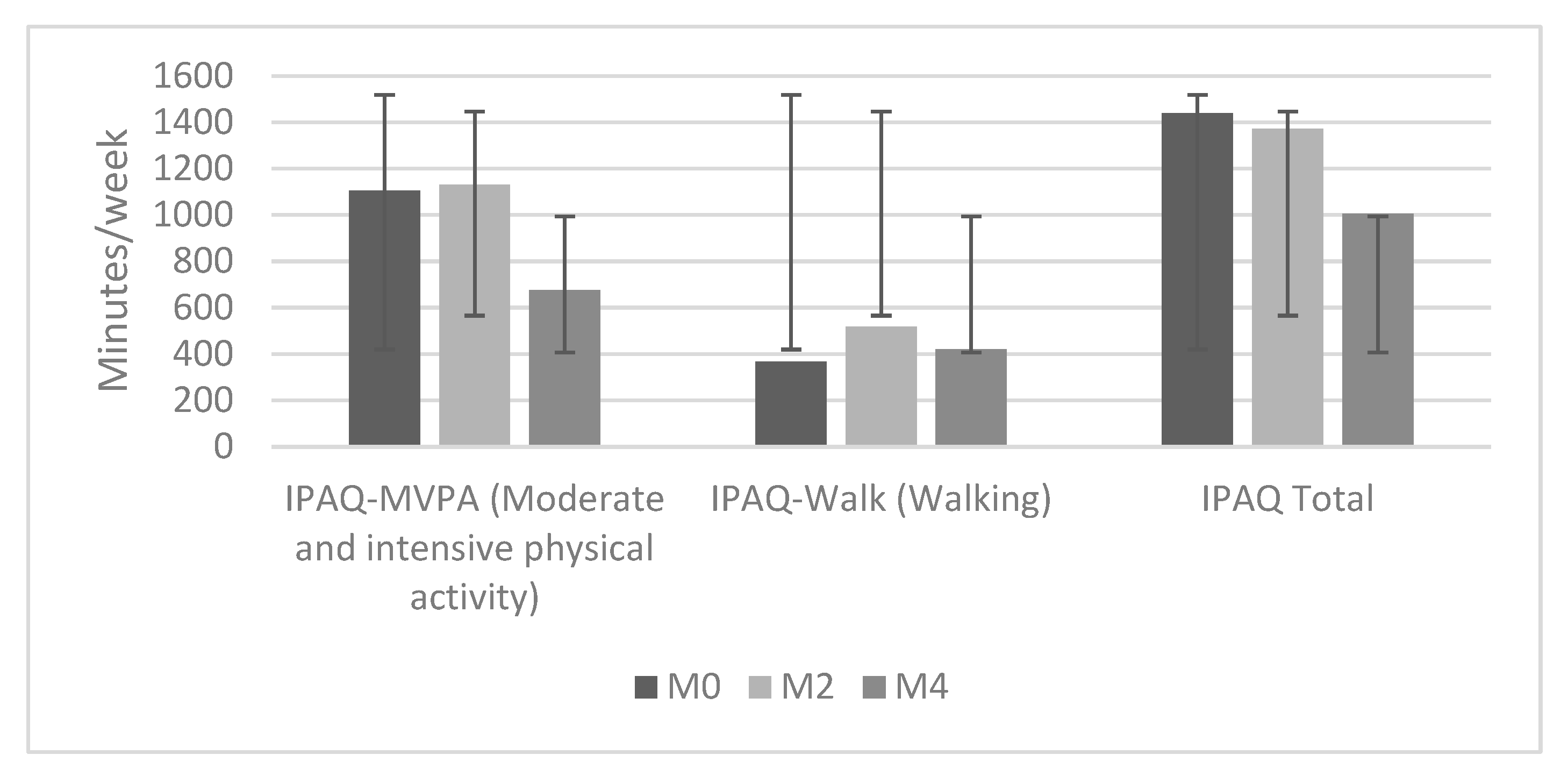

| M2 and M4 PU questionnaire IPAQ Walk: Increase in the number of steps during the first half of the intervention, followed by a decrease | PA levels among PU | Pillar 2. Factors related to ST use affecting PA levels | No corresponding qualitative data |

| Log data PUs’ average number of weekly steps increased rapidly at the beginning of the study, peaked in the sixth week of use, and then began to decline. | Interview Various factors affected temporal changes in PA levels | ||

| Log data The average weekly total number of steps increased by 2855 steps (+7.7%) in week 12. | |||

| M2 and M4 SU questionnaire PU was more physically active due to use of ST M2: M = 2.8 (SD = 1.3); M4: M = 3.1 (SD = 1.3) Scale: 1 = does not apply at all… 5 = applies completely | No corresponding qualitative data | ||

| M2 and M4 PU questionnaire Importance of monitoring own PA M2: M = 4.1 (SD = 1.0); M4: M = 4.0 (SD = 0.6) Scale: 1 = not important at all … 5 = very important | Self-awareness of PA levels | Interview Relationship between an increase in PA levels and self-awareness of PA | |

| No corresponding quantitative data | n/a | Interview Sexagenarians more than septuagenarians mentioned increased self-awareness of PA |

| Quantitative Data | Quantitative Categories | Pillar | Qualitative Categories (Themes Derived from the Thematic Analysis) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M2 and M4 PU and SU questionnaire The perceived usefulness of ST—PUs M2: M = 3.7 (SD = 0.6); M4: M = 3.9 (SD = 0.8) The perceived usefulness of ST—SUs M2: M = 3.9 (SD = 0.7); M4: M = 3.3 (SD = 1.2) Scale: 1 = not at all useful … 5 = very useful | Usefulness of ST increased over time for PUs who completed the study | Pillar 3. Increased usefulness of ST for PUs who completed the study | Interview Half of PUs who completed the intervention perceived ST as useful |

| Open-ended questions (M2 and M4 PU and SU questionnaire) Perceived usefulness expressed by some PUs and SUs during the study | |||

| No corresponding quantitative data | n/a | Interview ST was most useful for tracking PA, improving self-awareness of one’s PA, encouraging more PA, and ensuring safety | |

| No corresponding quantitative data | n/a | Interview ST of no value to PUs experiencing various technical problems that make ST unreliable | |

| M2 and M4 PU questionnaire Following on activity on (almost) daily basis: M2 and M4: 69.2% Activity monitoring was the most frequently used functionality. | Activity monitoring as most useful functionality | Pillar 4. Activity monitoring as the most useful functionality of the solution | No corresponding qualitative categories |

| M2 and M4 PU questionnaire Functionalities rated as the most useful—M2 Activity monitoring: M = 4.1 (SD = 1.0) Setting activity goals: M = 3.7 (SD = 1.3) Functionalities rated as the most useful—M4 Activity monitoring: M = 4.0 (SD = 0.6) Sending help to relatives or family members while being outdoors: M = 3.2 (SD = 1.7) Fall risk assessment: M = 3.2 (SD = 1.4) Scale: 1 = not at all useful … 5 = very useful | Interview The most useful functionality was counting steps, followed by safety features | ||

| M2 and M4 PU questionnaire Frequency of problems when using ST in the last two months a. Never: M2: 1 PU; M4: 3 PU b. Less frequently than twice a week: M2: 3 PU; M4: 7 PU c. At least three times per week: M2: 5 PU; M4:5 PU | Technical problems with ST | Pillar 5. The influence of technical problems on usefulness | Interview ST of no value to PUs experiencing various technical problems that make ST unreliable |

| M2 and M4 PU questionnaire Perceived usefulness of ST sexagenarians M2: M = 4.4 (SD = 0.7) M4: M = 4.4 (SD = 0.8) Perceived usefulness of ST—septuagenarians M2: M = 2.9 (SD = 1.2); M4: M = 3.5 (SD = 1.1) Scale: 1 = not at all useful … 5 = very useful | Perceived usefulness influenced by age and prior experiences with WAT | Pillar 6. The influence of age and previous experience with ST on usefulness | Interview Perceived usefulness of the solution higher among sexagenarians than septuagenarians |

| M4 PU questionnaire Perceived usefulness of ST based on previous experience with activity tracking No prior experience: 4.2 (SD = 1.0) Prior experience: 3.9 (SD = 1.1) Scale: 1 = not at all useful … 5 = very useful | Interview Differences in perceived usefulness evident between those with and without prior experience with activity-tracking solutions |

| PIADS | M0 2 | M2 | M4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Happiness | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.7) |

| Independence | 0.6 (1.0) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.8) |

| Self-esteem | 0.6 (1.0) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.5) |

| Productivity | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.6) |

| Quality of life | 0.9 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.9) |

| Sense of control | 0.9 (0.9) | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.4 (0.6) |

| Ability to participate | 0.8 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.8) |

| Eagerness to try new things | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.3 (1.0) | 1.3 (1.1) |

| Ability to adapt to the activities of daily living | 1.1 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.7) |

| Ability to take advantage of opportunities | 1.1 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.9) |

| Feeling safe 1 | n.d. 3 | n.d. 3 | 1.00 (0.9) |

| Total M (SD) Q1 Q3 | 0.84 (0.7) 0.40 1.0 | 0.60 (0.48) 0.25 0.85 | 0.59 (0.63) 0.05 0.85 |

| Quantitative Data | Quantitative Categories | Pillar | Qualitative Categories (Themes Derived from the Thematic Analysis) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M2 and M4 PU questionnaire No negative effects of using ST were found. Overall ratings of the effects of use ranged from 0.3 to 1.3 at M2 and M4. Scale: −3 = greatly decreased … 3 = greatly increased; 0 = no decrease or increase | Moderate psychological effects of ST use | Pillar 7. Moderate psychological effect of ST use | Interview and Open-ended questions (M2 and M4 PU questionnaire Technical issues and the demands of ST brought to some PUs negative psychological outcomes |

| M4 PU questionnaire At M4, the use of ST affected feelings of safety: M = 1.0 (SD = 0.9). The eagerness to try new things remained relatively high from the beginning to the end of the study (M4: 1.3 (SD = 1.1)). Scale: −3 = greatly decreased … 3 = greatly increased | Increased feeling of safety as a result of ST use | Interview PUs with a positive experience with ST reported an increased feeling of safety when walking around | |

| No corresponding quantitative data | n/a | Open-ended questions (M2 and M4 SU questionnaire) Safety features of the ST solution important to SUs | |

| No corresponding quantitative data | n/a | Open-ended questions (M2 and M4 PU questionnaire) Safety features important regardless of older users still being very fit and active |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hvalič-Touzery, S.; Šetinc, M.; Dolničar, V. Benefits of a Wearable Activity Tracker with Safety Features for Older Adults: An Intervention Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315723

Hvalič-Touzery S, Šetinc M, Dolničar V. Benefits of a Wearable Activity Tracker with Safety Features for Older Adults: An Intervention Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315723

Chicago/Turabian StyleHvalič-Touzery, Simona, Mojca Šetinc, and Vesna Dolničar. 2022. "Benefits of a Wearable Activity Tracker with Safety Features for Older Adults: An Intervention Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315723

APA StyleHvalič-Touzery, S., Šetinc, M., & Dolničar, V. (2022). Benefits of a Wearable Activity Tracker with Safety Features for Older Adults: An Intervention Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315723