Food Accessibility in the Suburbs of the Metropolitan City of Antwerp (Belgium): A Factor of Concern in Local Public Health and Active and Healthy Aging

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Aging and Limited Mobility

1.2. Antwerp and the 3RFD

2. Objectives

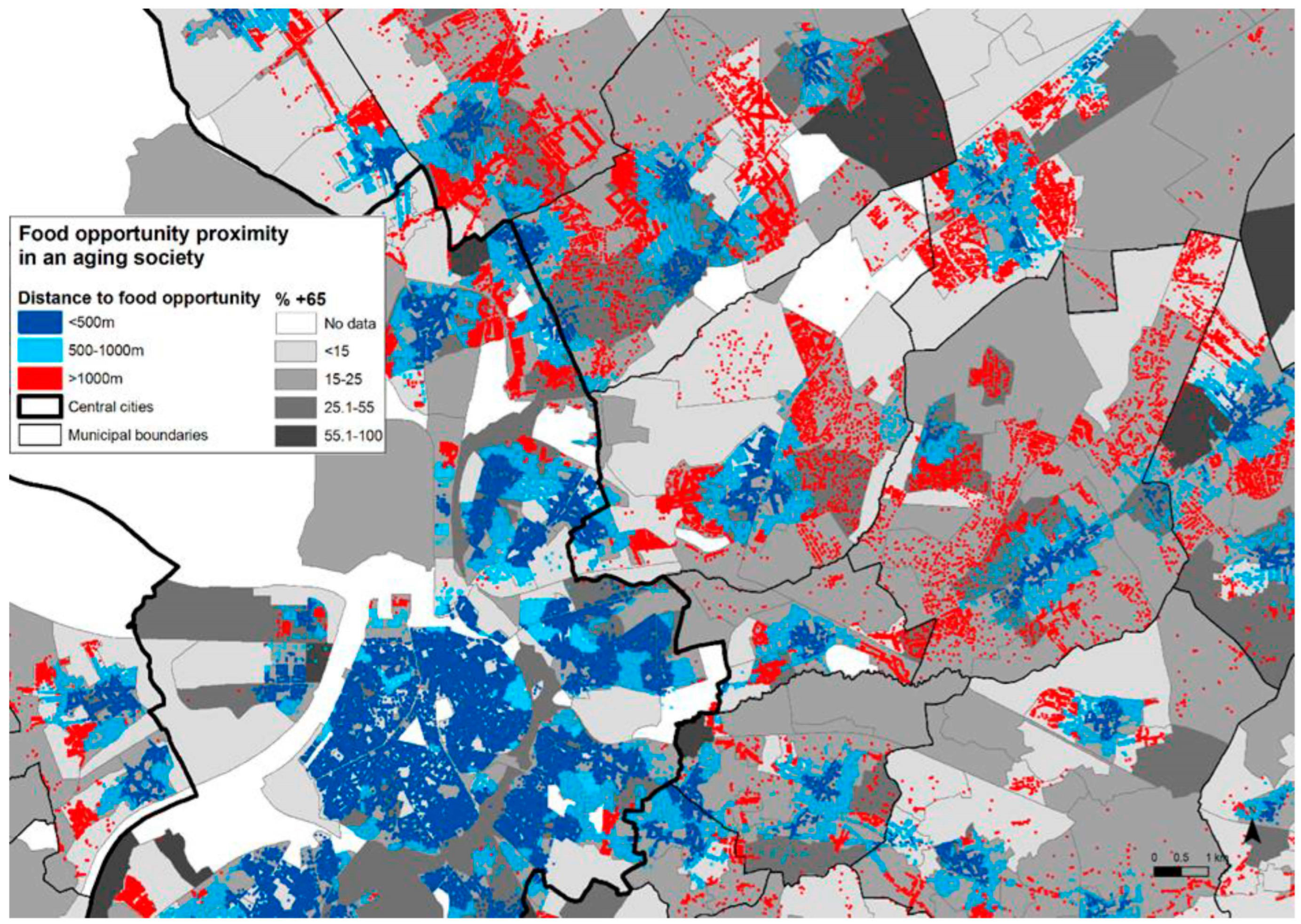

3. Physical Accessibility of Food

4. Online Accessibility of Food

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurostat. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_statistics_on_population_developments (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Beard, J.R.; Officer, A.; de Carvalho, I.A.; Sadana, R.; Pot, A.M.; Michel, J.-P.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; Epping-Jordan, J.E.; Peeters, G.M.E.E.; Mahanani, W.R.; et al. The World report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roller-Wirnsberger, R.; Liotta, G.; Lindner, S.; Iaccarino, G.; De Luca, V.; Geurden, B.; Maggio, M.; Longobucco, Y.; Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.; Cano, A.; et al. Public health and clinical approach to proactive management of frailty in multidimensional arena. Ann. Ig 2021, 33, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Barber, R.M.; Foreman, K.J.; Ozgoren, A.A.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abera, S.F.; Aboyans, V.; Abraham, J.P.; Abubakar, I.; Abu-Rmeileh, N.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990–2013: Quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet 2015, 386, 2145–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, E.J.; Visser, M.; Wagtendonk, A.J.; Noordzij, J.M.; Lakerveld, J. Associations of changes in neighbourhood walkability with changes in walking activity in older adults: A fixed effects analysis. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freiberger, E.; Sieber, C.C.; Kob, R. Mobility in Older Community-Dwelling Persons: A Narrative Review. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fávaro-Moreira, N.C.; Krausch-Hofmann, S.; Matthys, C.; Vereecken, C.; Vanhauwaert, E.; Declercq, A.; Bekkering, G.E.; Duyck, J. Risk Factors for Malnutrition in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of the Literature Based on Longitudinal Data. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pooler, J.A.; Hartline-Grafton, H.; DeBor, M.; Sudore, R.L.; Seligman, H.K. Food Insecurity: A Key Social Determinant of Health for Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengeveld, L.M.; Wijnhoven, H.A.H.; Olthof, M.R.; Brouwer, I.A.; Simonsick, E.M.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Houston, D.K.; Newman, A.B.; Visser, M. Prospective Associations of Diet Quality with Incident Frailty in Older Adults: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, S.; Collins, P.; Rattray, M. Identifying and Managing Malnutrition, Frailty and Sarcopenia in the Community: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geurden, B.; Franck, E.; Weyler, J.; Ysebaert, D. The Risk of Malnutrition in Community-Living Elderly on Admission to Hospital for Major Surgery. Acta Chir. Belg. 2015, 115, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geurden, B.; Franck, E.; Lopez Hartmann, M.; Weyler, J.; Ysebaert, D. Prevalence of ‘being at risk of malnutrition’ and associated factors in adult patients receiving nursing care at home in Belgium. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2015, 21, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.X.L.; Höchenberger, R.; Busch, N.A.; Bergmann, M.; Ohla, K. Associations between Taste and Smell Sensitivity, Preference and Quality of Life in Healthy Aging—The NutriAct Family Study Examinations (NFSE) Cohort. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzolino, D.; Passarelli, P.C.; De Angelis, P.; Piccirillo, G.B.; D’Addona, A.; Cesari, M. Poor Oral Health as a Determinant of Malnutrition and Sarcopenia. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, W.E.; Haverkort, E.B.; Algra, Y.A.; Mollema, J.; Hollaar, V.R.Y.; Naumann, E.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Jerković-Ćosić, K. The association between polypharmacy and malnutrition(risk) in older people: A systematic review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 49, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simões, P.; Amaral, A.P.; Rocha, C. Malnutrition in elderly: Relationship with depression, loneliness and quality of life. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31 (Suppl. S2), ckab120-093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.D. Did the Food Environment Cause the Obesity Epidemic? Obesity 2018, 26, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooksey-Stowers, K.; Schwartz, M.B.; Brownell, K.D. Food Swamps Predict Obesity Rates Better than Food Deserts in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulac, J.; Kristjansson, E.; Cummins, S. A Systematic Review of Food Deserts, 1966–2007. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2009, 6, A105. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, K.; Mattioli, G.; Verlinghieri, E.; Guzman, A. Transport poverty and its adverse social consequences. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Transport; Thomas Telford Ltd.: London, UK, 2016; Volume 169, pp. 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, G. Where Sustainable Transport and Social Exclusion Meet: Households without Cars and Car Dependence in Great Britain. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2014, 16, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Richardson, T.; Smyth, P.; Vella-Brodrick, D.; Hine, J.; Lucas, K.; Stanley, J.; Morris, J.; Kinnear, R.; Stanley, J. Investigating links between transport disadvantage, social exclusion and well-being in Melbourne—Preliminary results. Transp. Policy 2009, 16, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K.; Bates, J.; Moore, J.; Carrasco, J.A. Modelling the relationship between travel behaviours and social disadvantage. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 85, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, G.; Philips, I.; Anable, J.; Chatterton, T. Vulnerability to motor fuel price increases: Socio-spatial patterns in England. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 78, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osička, J.; Černoch, F. European energy politics after Ukraine: The road ahead. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 91, 102757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vrij, E.; Vanoutrive, T. ‘No-one visits me anymore’: Low Emission Zones and social exclusion via sustainable transport policy. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2022, 24, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, B.H.; Oxley, J.A.; Chen, W.S.; Yap, K.K.; Song, K.P.; Lee, S.W.H. To reduce or to cease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative studies on self-regulation of driving. J. Saf. Res. 2019, 70, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Park, K. The Predictors of Driving Cessation among Older Drivers in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, G.; Rottunda, S. Older adults’ perspectives on driving cessation. J. Aging Stud. 2006, 20, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravensbergen, L.; Newbold, K.B.; Ganann, R.; Sinding, C. ‘Mobility work’: Older adults’ experiences using public transportation. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 97, 103221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.; Newbold, K.B.; Scott, D.M.; Vrkljan, B.; Grenier, A. To drive or not to drive: Driving cessation amongst older adults in rural and small towns in Canada. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 86, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirker, W.; Katzenschlager, R. Gait disorders in adults and the elderly. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2017, 129, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, L.A.; Fleischhacker, S.; Anderson-Steeves, B.; Harper, K.; Winkler, M.; Racine, E.; Baquero, B.; Gittelsohn, J. Healthy Food Retail during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Challenges and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, H.J. Food Deserts: Towards the Development of a Classification. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2006, 88, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, V.; Cant, J.; Vandevijvere, S. The Changing Landscape of Food Deserts and Swamps over More than a Decade in Flanders, Belgium. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhetsel, A.; Beckers, J.; Cant, J. Regional retail landscapes emerging from spatial network analysis. Reg. Stud. 2022, 56, 1829–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.; Teller, J. Self-Reinforcing Processes Governing Urban Sprawl in Belgium: Evidence over Six Decades. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bervoets, W.; van de Weijer, M.; Vanneste, D.; Vanderstraeten, L.; Ryckewaert, M.; Heynen, H. Towards a sustainable transformation of the detached houses in peri-urban Flanders, Belgium. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2015, 8, 302–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhetsel, A.; Thomas, I.; Beelen, M. Commuting in Belgian metropolitan areas: The power of the Alonso-Muth model. J. Transp. Land Use 2010, 2, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillebeeckx, E.; De Decker, P.; Oosterlynck, S. Internationale Immigratie en Vergrijzing in Vlaanderen: Data en Kaarten; Steunpunt Ruimte: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Buffel, T.; Donder, L.D.; Phillipson, C.; Witte, N.D.; Dury, S.; Verté, D. Place Attachment Among Older Adults Living in Four Communities in Flanders, Belgium. Hous. Stud. 2014, 29, 800–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, N.; Smetcoren, A.-S.; De Donder, L.; Dury, S.; Buffel, T.; Kardol, T.; Verté, D. Een Huis? Een Thuis! Over Ouderen en Wonen; VIEWZ. Vanden Broele Publishers: Bruges, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meeus, B.; De Decker, P. Staying Put! A Housing Pathway Analysis of Residential Stability in Belgium. Hous. Stud. 2015, 30, 1116–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volckaert, E.; Schillebeeckx, E.; De Decker, P. Beyond nostalgia: Older people’s perspectives on informal care in rural Flanders. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 87, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhetsel, A.; Beckers, J.; De Meyere, M. Assessing Daily Urban Systems: A Heterogeneous Commuting Network Approach. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2018, 18, 633–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeDoux, T.F.; Vojnovic, I. Examining the role between the residential neighborhood food environment and diet among low-income households in Detroit, Michigan. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 55, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollberding, N.J.; Nigg, C.R.; Geller, K.S.; Horwath, C.C.; Motl, R.W.; Dishman, R.K. Food Outlet Accessibility and Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. Am. J. Health Promot. 2012, 26, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Data & Analyse Vlaamse Provincies. 2022. Provincies.in.Cijfers.be—Je Stad of Gemeente in Kaart. Available online: https://provincies.incijfers.be/databank (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Lee, J.H.; Tan, T.H. Neighborhood Walkability or Third Places? Determinants of Social Support and Loneliness among Older Adults. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Altinay, L.; Sun, N.; Wang, X.L. The influence of social interactions on senior customers’ experiences and loneliness. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2773–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, S.; Saloner, G. Economics and Electronic Commerce. J. Econ. Perspect. 2001, 15, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, R.T.; Lemon, K.N. E-Service and the Consumer. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2001, 5, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.; Cárdenas, I.; Verhetsel, A. Identifying the geography of online shopping adoption in Belgium. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 45, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G.; Thompson, C.; Birkin, M. The emerging geography of e-commerce in British retailing. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2015, 2, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, R.; Derudder, B.; Witlox, F. The geography of e-shopping in China: On the role of physical and virtual accessibility. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, E.W.; Lo, A.; Hall, M.G.; Taillie, L.S.; Ng, S.W. Prevalence and demographic correlates of online grocery shopping: Results from a nationally representative survey during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 3079–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, A.; Alexiou, A.; Savani, R. Mapping the geodemographics of digital inequality in Great Britain: An integration of machine learning into small area estimation. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2020, 82, 101486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.; Dall’Olmo Riley, F.; Riley, D.; Hand, C. Online and store patronage: A typology of grocery shoppers. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.; Alamanos, E.; Papagiannidis, S.; Bourlakis, M. Does social exclusion influence multiple channel use? The interconnections with community, happiness, and well-being. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.; Bourlakis, M.; Alamanos, E.; Papagiannidis, S.; Brakus, J.J. Value Co-Creation through Multiple Shopping Channels: The Interconnections with Social Exclusion and Well-Being. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2017, 21, 517–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, N.; Urquhart, R.; Newing, A.; Heppenstall, A. Sociodemographic and spatial disaggregation of e-commerce channel use in the grocery market in Great Britain. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby-Hawkins, E.; Birkin, M.; Clarke, G. An investigation into the geography of corporate e-commerce sales in the UK grocery market. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 1148–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.; Weekx, S.; Beutels, P.; Verhetsel, A. COVID-19 and retail: The catalyst for e-commerce in Belgium? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Ślusarczyk, B.; Hajizada, S.; Kovalyova, I.; Sakhbieva, A. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Online Consumer Purchasing Behavior. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2263–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jílková, P.; Králová, P. Digital Consumer Behaviour and eCommerce Trends during the COVID-19 Crisis. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2021, 27, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baarsma, B.; Groenewegen, J. COVID-19 and the Demand for Online Grocery Shopping: Empirical Evidence from the Netherlands. De Econ. 2021, 169, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezirgani, A.; Lachapelle, U. Online grocery shopping for the elderly in Quebec, Canada: The role of mobility impediments and past online shopping experience. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 25, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, I.D.; Dewulf, W.; Vanelslander, T.; Smet, C.; Beckers, J. The E-Commerce Parcel Delivery Market and the Implications of Home B2C Deliveries Vs Pick-Up Points. Int. J. Transp. Econ. 2017, 44, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, S.; Koppenberg, M. Power imbalances in French food retailing: Evidence from a production function approach to estimate market power. Econ. Lett. 2020, 194, 109387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlebois, S.; Juhasz, M.; Music, J. Supply Chain Responsiveness to a (Post)-Pandemic Grocery and Food Service E-Commerce Economy: An Exploratory Canadian Case Study. Businesses 2021, 1, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headrick, G.; Khandpur, N.; Perez, C.; Taillie, L.S.; Bleich, S.N.; Rimm, E.B.; Moran, A. Content Analysis of Online Grocery Retail Policies and Practices Affecting Healthy Food Access. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, Z.; Hu, Y.; Charkhgard, H.; Himmelgreen, D.; Kwon, C. Creating grocery delivery hubs for food deserts at local convenience stores via spatial and temporal consolidation. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 82, 101301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Diaz, I.; Altuntas Vural, C.; Halldórsson, Á. Assessing the inequalities in access to online delivery services and the way COVID-19 pandemic affects marginalization. Transp. Policy 2021, 109, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newing, A.; Hood, N.; Videira, F.; Lewis, J. ‘Sorry we do not deliver to your area’: Geographical inequalities in online groceries provision. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2022, 32, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquhart, R.; Newing, A.; Hood, N.; Heppenstall, A. Last-Mile Capacity Constraints in Online Grocery Fulfilment in Great Britain. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 636–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, E.; Seidel, S.; Blanquart, C.; Dablanc, L.; Lenz, B. The Impact of E-commerce on Final Deliveries: Alternative Parcel Delivery Services in France and Germany. Transp. Res. Procedia 2014, 4, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjevic, M.; Winkenbach, M.; Merchán, D. Integrating collection-and-delivery points in the strategic design of urban last-mile e-commerce distribution networks. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 131, 37–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautela, H.; Janjevic, M.; Winkenbach, M. Investigating the financial impact of collection-and-delivery points in last-mile E-commerce distribution. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 100681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.; McKinnon, A.; Cherrett, T.; McLeod, F.; Song, L. Carbon Dioxide Benefits of Using Collection–Delivery Points for Failed Home Deliveries in the United Kingdom. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2191, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Guan, W.; Cherrett, T.; Li, B. Quantifying the Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Local Collection-and-Delivery Points for Last-Mile Deliveries. Transp. Res. Rec. 2013, 2340, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossolov, A.; Rossolova, H.; Holguín-Veras, J. Online and in-store purchase behavior: Shopping channel choice in a developing economy. Transportation 2021, 48, 3143–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, A.; Kusumastuti, D.; Nicholson, A. Establishing Collection and Delivery Points to Encourage the Use of Active Transport: A Case Study in New Zealand Using a Consumer-Centric Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salirrosas, E.; Rondon-Eusebio, R. Influence of Retail e-Commerce Website Design on Perceived Risk in Online Purchases. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Business and Industrial Research (ICBIR), Bangkok, Thailand, 19–20 May 2022; pp. 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.; Verhetsel, A. The sustainability of the urban layer of e-commerce deliveries: The Belgian collection and delivery point networks. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 29, 2300–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollenburg, J.; Hübner, A.; Kuhn, H.; Trautrims, A. From bricks-and-mortar to bricks-and-clicks: Logistics networks in omni-channel grocery retailing. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geurden, B.; Cant, J.; Beckers, J. Food Accessibility in the Suburbs of the Metropolitan City of Antwerp (Belgium): A Factor of Concern in Local Public Health and Active and Healthy Aging. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315754

Geurden B, Cant J, Beckers J. Food Accessibility in the Suburbs of the Metropolitan City of Antwerp (Belgium): A Factor of Concern in Local Public Health and Active and Healthy Aging. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315754

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeurden, Bart, Jeroen Cant, and Joris Beckers. 2022. "Food Accessibility in the Suburbs of the Metropolitan City of Antwerp (Belgium): A Factor of Concern in Local Public Health and Active and Healthy Aging" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315754

APA StyleGeurden, B., Cant, J., & Beckers, J. (2022). Food Accessibility in the Suburbs of the Metropolitan City of Antwerp (Belgium): A Factor of Concern in Local Public Health and Active and Healthy Aging. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315754