Gender-Based Violence in the Asia-Pacific Region during COVID-19: A Hidden Pandemic behind Closed Doors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sampling and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Increasing GBV Incidence

3.1.1. High Prevalence of GBV before the Pandemic

“One out of three women in Mongolia experiences some kind of violence each year. So it’s very high, and … one out of two women have experienced any kind of violence in a lifetime.”(MN1F)

“So in a male-dominated society where 60% of women were already suffering from one or the other type of GBV. This is going to be much higher now.”(PK1F)

3.1.2. Increased Reports of GBV: The ‘Shadow Pandemic’

“Globally it has increased, even in Malaysia. I think there were more than 2000 cases of domestic violence reported by the women’s organization.”(MY1F)

“We know that GBV in terms of the incidence has increased significantly. And especially in the case of Mongolia, we know that compared to the same period of last year, this year by end of October incidents of GBV increased by 44%.”(MN2F)

3.1.3. GBV Affects Society: Absenteeism Due to Violence

“I talked to this CEO of this company; they are very interested in this because they are impacted by domestic violence. There’s a very high turnover of female employees because of domestic violence. They don’t sometimes show up, really impacting their business. So they want to address this concern.”(MN1F)

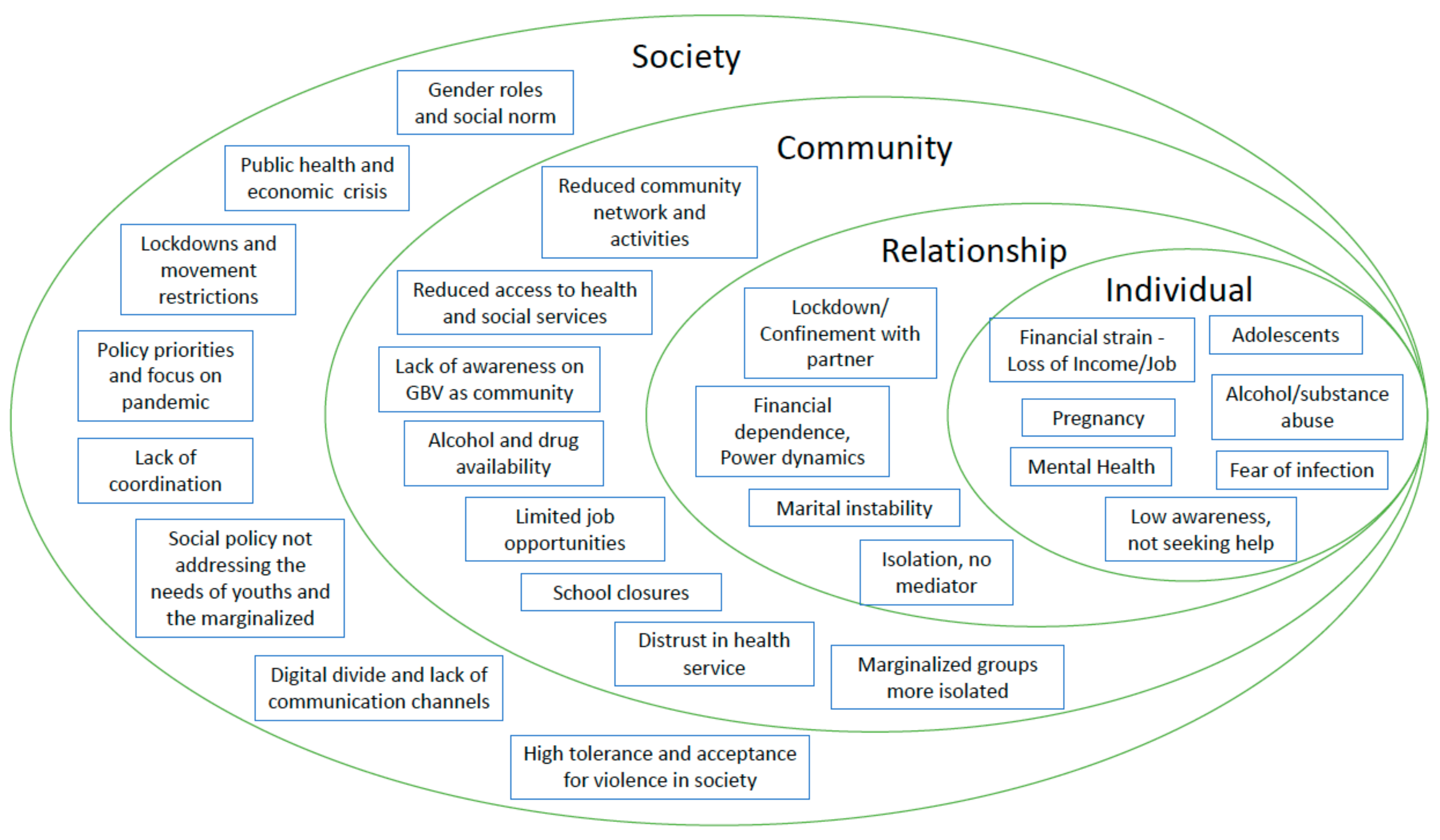

3.2. Underlying Factors for Increased GBV and Reduced Access to Quality Services

3.2.1. First Level: Individual

Anxiety from Economic Strain

“Because of the anxiety and the tension and unemployment and where to go and from where to bring the money to home and all this, the men just express their anger on the ladies at home.”(PK1F)

Increased Drug and Alcohol Use

“And there’s so much drug abuse, more than alcohol. There’s a lot of illicit drugs that are being used in Pakistan. And with the people losing jobs and depression, all that has gone up.”(PK2M)

“Even though the government banned the sale of alcohol, and alcoholism is also a big issue in Mongolia, men drink a lot […] and they lose control by drinking alcohol.”(MN1F)

Adolescents and Children

“When I go to a one-stop service centre, I see more girls than the grown-ups. They are basically the victims of sexual violence by a family member, usually like step-father or uncle or grandfather.”(MN1F)

“But the problem was through the economic impact where you see the girls dropping out and that spiking up girls and pregnancy and marriage rates.”(LA1F)

Pregnant Women at Higher Risk

“Actually, the centre for forensic medicine reported us five suicide cases of pregnant women, which they said that’s nearly unprecedented […] And we suspect that there had been another three maternal deaths this year due to violence… intimate partner violence… these cases, and so we see the increased number of incidental maternal deaths.”(MN3M)

Discrimination and Stigma of Marginalised Groups

“We have anecdotal evidence from different countries, that internally-displaced people, marginalised people, young people, unmarried people, people with different orientations and so on, […] maybe even sex-workers and others, they all have some level of stigma, and it varies, but they are the ones who need to be reached out to because the level of discrimination is pretty high.”(MY1F)

3.2.2. Second Level: Relationships

Isolation and Confinement with Perpetrators

“On GBV, as in all countries globally, because of the lockdown and the fact that women were trapped in their families and often with their abusers, there was an increase in domestic violence, a very high increase in domestic violence. At the same time, women had no access to the support system that exists in the country.”(NP1F)

Unable to Seek Help

“Most of them tried to hide it actually. When they come and complain about what makes them in pain, I casually ask them, and they eventually tell me that their husband has physically abused them. […] because most of them won’t tell us. Some of them are brought here by their husband, and they don’t dare to say anything, but we can observe and see that they are having pressure from their husband.”(KH11UF)

“And in fact, what the police records show is that in the initial period, the number of calls in the police helplines reduced. And that is clearly because women who are in lockdown do not have the privacy to make those calls in safety. So those calls reduced, and that was not so much a signal that there’s less GBV, but it was because of the context. And then when the lockdown was eased, I think they started receiving more calls.”(NP1F)

3.2.3. Third Level: Community

SRH Services Short-Staffed Due to COVID-19 Response

“COVID definitely stopped non-essential health services. […] Especially, if it is domestic violence, the people will still think this is their own problem, instead of this is the government or the country problem…”(MM2M)

‘‘When there is no supplies available, when there is no access to the supply for supplies, when there is a lockdown and then there’s an access issue there is a fear that there will be a lot of unwanted pregnancies.’’(PK2M)

Fear of Infection among Service Providers

“What we also realized is that staff working in those shelter homes—one-stop service centres, they were afraid to have a client, you know? They closed it because it was a new disease for them and then they were afraid to get COVID.”(MN2F)

Lack of Information about Helplines

“In Vietnam now we have the hotline; one hotline that people with violence can call. […] But people have to know the number…”(VN2M)

School Closures Affecting the Safety of Children and Adolescents

“During the lockdown what we had is like the boys and girls having to spend more time in households, they were more exposed to this domestic violence.”(LA3F)

Distrust in Healthcare Services

“And then also people not trusting the health facilities, not trusting the quality of health services you receive…”(TL1F)

3.2.4. Fourth Level: Societal

GBV Not Prioritised during Pandemic Response

“You don’t even see a GBV-related department in any of the government systems. […] That might not be like intentional, because the staff are not that many, and especially if the COVID come up right? […] I think they recently launched the GBV guiding manual, maybe two to three years ago. But you know, that uptake of this, the whole GBV as an essential service, is not there yet.”(MM2M)

Culture and Social Norms

“Women here that face sexual abuse, it’s not easy to solve. It’s not easy to tell, they are still shy… If there is such a case, it needs months, then they tell us, they don’t know what to do.”(KH14RF)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- García-Moreno, C.; Pallitto, C.; Devries, K.; Stöckl, H.; Watts, C.; Abrahams, N. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman, L.E.; Green, Y.T.; Marks, J.S.; Thacker, S.B. Violence against women as a public health issue: Comments from the, C.D.C. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2000, 19, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Violence Against Women; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/violence-against-women (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Krug, E.G.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Mercy, J.A.; Zwi, A.B.; Lozano, R. (Eds.) World Report on Violence and Health; WHO: Geneva, Swittzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ellsberg, M.C. Violence against women: A global public health crisis. Scand. J. Public Health 2006, 34, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Remarks on International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2018-11-19/international-day-for-elimination-of-violence-against-women-remarks (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Say, L.; Chou, D.; Gemmill, A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Moller, A.; Daniels, J.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Temmerman, M.; Alkema, L. Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e323–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Global Study on Homicide: Gender Related Killing of Women and Girls 2018; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Day, T.; McKenna, K.; Bowlus, A. The Economic Costs of Violence Against Women: An Evaluation of the Literature; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2005; p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- IASC. Guidelines for Integrating Gender-Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action, 2015; IASC: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/working-group/iasc-guidelines-integrating-gender-based-violence-interventions-humanitarian-action-2015 (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- UNFPA. Minimum Standards for Prevention and Response to Gender-Based Violence in Emergencies. 2015. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/featured-publication/gbvie-standards (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- UN Women. The Shadow Pandemic: Violence against Women during COVID-19. UN Women, 2021. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/in-focus-gender-equality-in-covid-19-response/violence-against-women-during-covid-19 (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 and Violence Against Women: What the Health Sector/System Can Do, 7 April 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331699 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Boserup, B.; McKenney, M.; Elkbuli, A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 2753–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, N.L.; DiPasquale, A.M.; Dillabough, K.; Schneider, P.S. Health care practitioners’ responsibility to address intimate partner violence related to the COVID-19 pandemic. CMAJ 2020, 192, E609–E610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahase, E. COVID-19: EU states report 60% rise in emergency calls about domestic violence. BMJ 2020, 369, 1872. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. COVID-19 and Ending Violence Against Women and Girls. 2020. Available online: https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/04/covid-19-and-ending-violence-against-women-and-girls (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Bradbury-Jones, C.; Isham, L. The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2047–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vora, M.; Malathesh, B.C.; Das, S.; Chatterjee, S.S. COVID-19 and domestic violence against women. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 53, 102227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.-C.; Henke, A. COVID-19, staying at home, and domestic violence. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2021, 19, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Intensification of Efforts to Eliminate All Forms of Violence Against Women: Report of the Secretary-General. A /75/274. 2020. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3880918?ln=en (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Mazza, M.; Marano, G.; Lai, C.; Janiria, L.; Sania, G. Danger in danger: Interpersonal violence during COVID-19 quarantine. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 113046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viero, A.; Barbara, G.; Montisci, M.; Kustermann, K.; Cattaneo, C. Violence against women in the COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the literature and a call for shared strategies to tackle health and social emergencies. Forensic Sci. Int. 2021, 319, 110650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN.ESCAP. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Violence Against Women in Asia and the Pacific. 2020. Available online: https://repository.unescap.org/handle/20.500.12870/911 (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Baig, M.A.M.; Ali, S.; Tunio, N.A. Domestic Violence Amid COVID-19 Pandemic: Pakistan’s Perspective. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2020, 32, 525–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CDC. The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Violence Prevention; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, L.L. Violence Against Women: An Integrated, Ecological Framework. Violence Women 1998, 4, 262–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Women. The Ecological Framework. 2013. Available online: https://www.endvawnow.org/en/articles/1509-the-ecological-framework.html (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- WHO. The Ecological Framework; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://www.who.int/violenceprevention/approach/ecology/en/ (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Dewitte, M.; Otten, C.; Walker, L. Making love in the time of corona—Considering relationships in lockdown. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2020, 17, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, D.N.; Pinto da Costa, M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the precipitation of intimate partner violence. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2020, 71, 101606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFPA. Update on UNFPA response to the COVID-19 pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/board-documents/main-document/FINAL_UNFPA_response_to_COVID-19_pandemic_-_vffs.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Stith, S.M.; Smith, D.B.; Penn, C.E.; Ward, D.B.; Tritt, D. Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2004, 10, 65–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Capaldi, D.M.; Knoble, N.B.; Shortt, J.W.; Kim, H.K. A Systematic Review of Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence. Partn. Abus. 2012, 3, 231–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherburn, D. Personal stress, financial stress and violence against women. Crime Justice Bull. 2011, 151, 1–12. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/agispt.20122937 (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Brand, J.E. The Far-Reaching Impact of Job Loss and Unemployment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Akel, M.; Berro, J.; Rahme, C.; Haddad, C.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. Violence Against Women During COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 0886260521997953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalotra, S.; GC Britto, D.; Pinotti, P.; Sampaio, B. Job Displacement, Unemployment Benefits and Domestic Violence; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3886839 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Matjasko, J.L.; Niolon, P.H.; Valle, L.A. The Role of Economic Factors and Economic Support in Preventing and Escaping from Intimate Partner Violence. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2013, 32, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipsey, M.W.; Wilson, D.B.; Cohen, M.A.; Derzon, J.H. Is There a Causal Relationship between Alcohol Use and Violence? A Synthesis of Evidence. In Recent Development in Alcoholism; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; Volume 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Molina, M.M.; Reingle, J.M.; Jennings, W.G. Does Alcohol Use Predict Violent Behaviors? The Relationship Between Alcohol Use and Violence in a Nationally Representative Longitudinal Sample. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2011, 9, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pollard, M.S.; Tucker, J.S.; Green, H.D. Changes in Adult Alcohol Use and Consequences During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2022942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugarman, D.E.; Greenfield, S.F. Alcohol and COVID-19: How Do We Respond to This Growing Public Health Crisis? J. Gen. Intern Med. 2021, 36, 214–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenilmez, M.I. The COVID-19 pandemic and the struggle to tackle gender-based violence. J. Adult Prot. 2020, 22, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, N.; Casey, S.E.; Carino, G.; McGovern, T. Lessons Never Learned: Crisis and gender-based violence. Dev. World Bioeth. 2020, 20, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merrill, K.A.; William, T.N.; Joyce, K.M.; Roos, L.E.; Protudjer, J.L. Potential psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on children: A scoping review of pandemics and epidemics. J. Glob. Health Rep. 2021, 4, e2020106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. COVID-19: A Threat to Progress Against Child Marriage. 2021. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/covid-19-a-threat-to-progress-against-child-marriage/ (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Ragavan, M.I.; Garcia, R.; Berger, R.P.; Miller, E. Supporting Intimate Partner Violence Survivors and Their Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20201276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. COVID-19 and Violence against Women. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/vaw-covid-19/en/ (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- NBC News. European Countries Develop New Ways to Tackle Domestic Violence During Lockdowns; NBC News: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/european-countries-develop-new-ways-tackle-domestic-violence-during-coronavirus-n1174301 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Government of UK. Pharmacies Launch Codeword Scheme to Offer ‘Lifeline’ to Domestic Abuse Victims, GOV.UK. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pharmacies-launch-codeword-scheme-to-offer-lifeline-to-domestic-abuse-victims (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Palermo, T.; Bleck, J.; Peterman, A. Tip of the Iceberg: Reporting and Gender-Based Violence in Developing Countries. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 179, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, S.; Silove, D.; Chey, T.; Ivancic, L.; Steel, Z.; Creamer, M.; Teesson, M.; Bryant, R.; McFarlane, A.C.; Mills, K.L.; et al. Lifetime prevalence of gender-based violence in women and the relationship with mental disorders and psychosocial function. JAMA 2011, 306, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Silove, D.; Baker, J.R.; Mohsin, M.; Teesson, M.; Creamer, M.; O’Donnell, M.; Forbes, D.; Carragher, N.; Slade, T.; Mills, K.; et al. The contribution of gender-based violence and network trauma to gender differences in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Evans, M.L.; Lindauer, M.; Farrell, M.E. A Pandemic within a Pandemic—Intimate Partner Violence during COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2302–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Women PL. Impact of COVID-19 on Violence Against Women and Girls and Service Provision: UN Women Rapid Assessment and Findings; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, B.J.; Tucker, J.D. Surviving in place: The coronavirus domestic violence syndemic. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 53, 102179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID | Country | Sector | Professional Role | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BG1M | Bangladesh | UN | Health System Specialist | Male |

| BG2M | Bangladesh | INGO | Country Director | Male |

| KH1M | Cambodia | UN | Programme Director | Male |

| KH2M | Cambodia | NGO | Country Director | Male |

| ID1F | Indonesia | UN | SRH Programme Specialist | Female |

| ID2F | Indonesia | UN | Adolescent SRH specialist | Female |

| LA1F | Laos | UN | Country Representative | Female |

| LA2F | Laos | UN | SRH Specialist | Female |

| LA3F | Laos | INGO | Head of Adolescence Programme | Female |

| MY1F | Malaysia | UN | Assistant Representative | Female |

| MY2M | Malaysia | INGO | Director SRH programme | Male |

| MN1F | Mongolia | UN | Head of Office | Female |

| MN2F | Mongolia | UN | Assistant Representative | Female |

| MN3M | Mongolia | UN | SRH Programme Specialist | Male |

| MM1M | Myanmar | UN | SRH Programme Specialist | Male |

| MM2M | Myanmar | UN | Programme Director | Male |

| NP1F | Nepal | UN | Representative | Female |

| NP2F | Nepal | UN | Assistant Representative | Female |

| NP3F | Nepal | MOH | Consultant | Female |

| PK1F | Pakistan | MD | Medical Director/Obstetrician | Female |

| PK2M | Pakistan | UN | Technical Specialist | Male |

| PH1F | Philippines | UN | Assistant Representative | Female |

| PH2F | Philippines | INGO | SRH Programme Specialist | Female |

| PH3F | Philippines | DOH | Programme Director | Female |

| TL1F | Timor-Leste | INGO | Country Director | Female |

| TL2M | Timor-Leste | INGO | Programme Director | Male |

| VN1F | Vietnam | NGO | Founder | Female |

| VN2M | Vietnam | UN | SRH Programme Specialist | Male |

| KH03RF | Cambodia | Provincial Health Department | MCH Senior Management | Female |

| KH04UF | Cambodia | Provincial Health Department | MCH Senior Management | Female |

| KH05RM | Cambodia | Provincial Health Department | MCH Senior Management | Male |

| KH06UM | Cambodia | Operational District | MCH Senior Management | Male |

| KH07RM | Cambodia | Operational District | MCH Senior Management | Male |

| KH08RF | Cambodia | Referral Hospital | Obstetrics Senior Management | Female |

| KH09RF | Cambodia | Referral Hospital | Obstetrics Senior Management | Female |

| KH10UF | Cambodia | Referral Hospital | Midwife | Female |

| KH11UF | Cambodia | Health Centre | Midwifery Senior Management | Female |

| KH12UF | Cambodia | Health Centre | Obstetrics | Female |

| KH13UF | Cambodia | Health Centre | Midwife | Female |

| KH14RF | Cambodia | Health Centre | STI Consultant | Female |

| KH15RF | Cambodia | Health Centre | Obstetrics Senior Management | Female |

| KH16RF | Cambodia | Health Centre | Obstetrics Senior Management | Female |

| KH17RF | Cambodia | Health Centre | Midwife | Female |

| KH18RM | Cambodia | Community | Village Health Support Group | Male |

| KH19RF | Cambodia | Community | Village Health Support Group | Female |

| KH20UF | Cambodia | Community | Village Health Support Group | Female |

| KH21UF | Cambodia | Community | Village Health Support Group | Female |

| KH22RF | Cambodia | Community | Village Health Support Group | Female |

| KH23UF | Cambodia | Community | Village Health Support Group | Female |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nagashima-Hayashi, M.; Durrance-Bagale, A.; Marzouk, M.; Ung, M.; Lam, S.T.; Neo, P.; Howard, N. Gender-Based Violence in the Asia-Pacific Region during COVID-19: A Hidden Pandemic behind Closed Doors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042239

Nagashima-Hayashi M, Durrance-Bagale A, Marzouk M, Ung M, Lam ST, Neo P, Howard N. Gender-Based Violence in the Asia-Pacific Region during COVID-19: A Hidden Pandemic behind Closed Doors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042239

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagashima-Hayashi, Michiko, Anna Durrance-Bagale, Manar Marzouk, Mengieng Ung, Sze Tung Lam, Pearlyn Neo, and Natasha Howard. 2022. "Gender-Based Violence in the Asia-Pacific Region during COVID-19: A Hidden Pandemic behind Closed Doors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042239

APA StyleNagashima-Hayashi, M., Durrance-Bagale, A., Marzouk, M., Ung, M., Lam, S. T., Neo, P., & Howard, N. (2022). Gender-Based Violence in the Asia-Pacific Region during COVID-19: A Hidden Pandemic behind Closed Doors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042239