Impacts of Emergency Remote Teaching on College Students Amid COVID-19 in the UAE

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Impact of ERT Dimensions

2.2. Impact of ERT on Mental Health

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey Design

- i.

- Psychological Distress

- ii.

- Quality of Courses

- iii.

- Academic Performance

- iv.

- Readiness for Future Work/Studies

3.2. Data Collection

Ethical Considerations

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. Measurement Validation

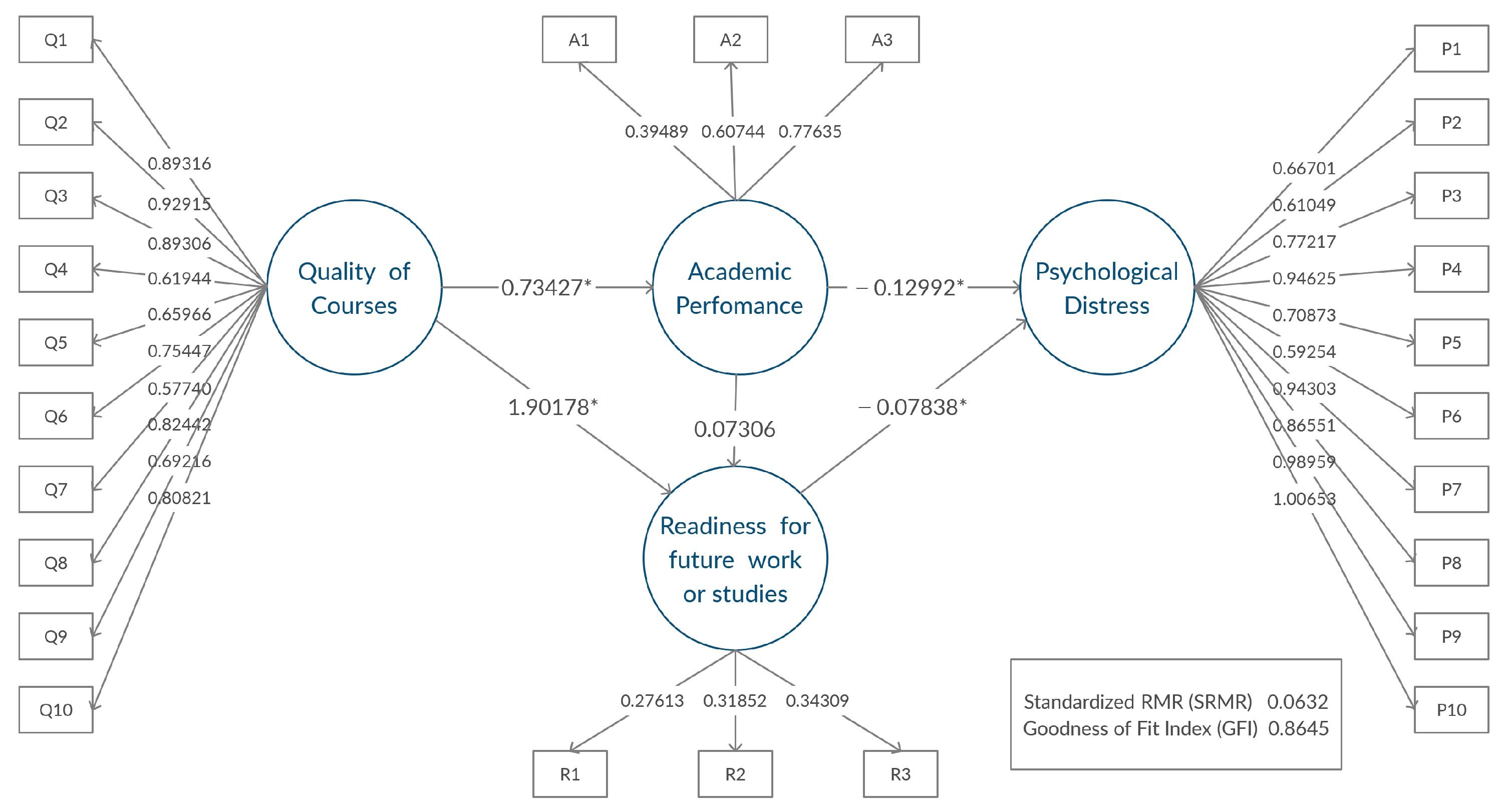

3.3.2. CFA Model

3.3.3. SEM Results

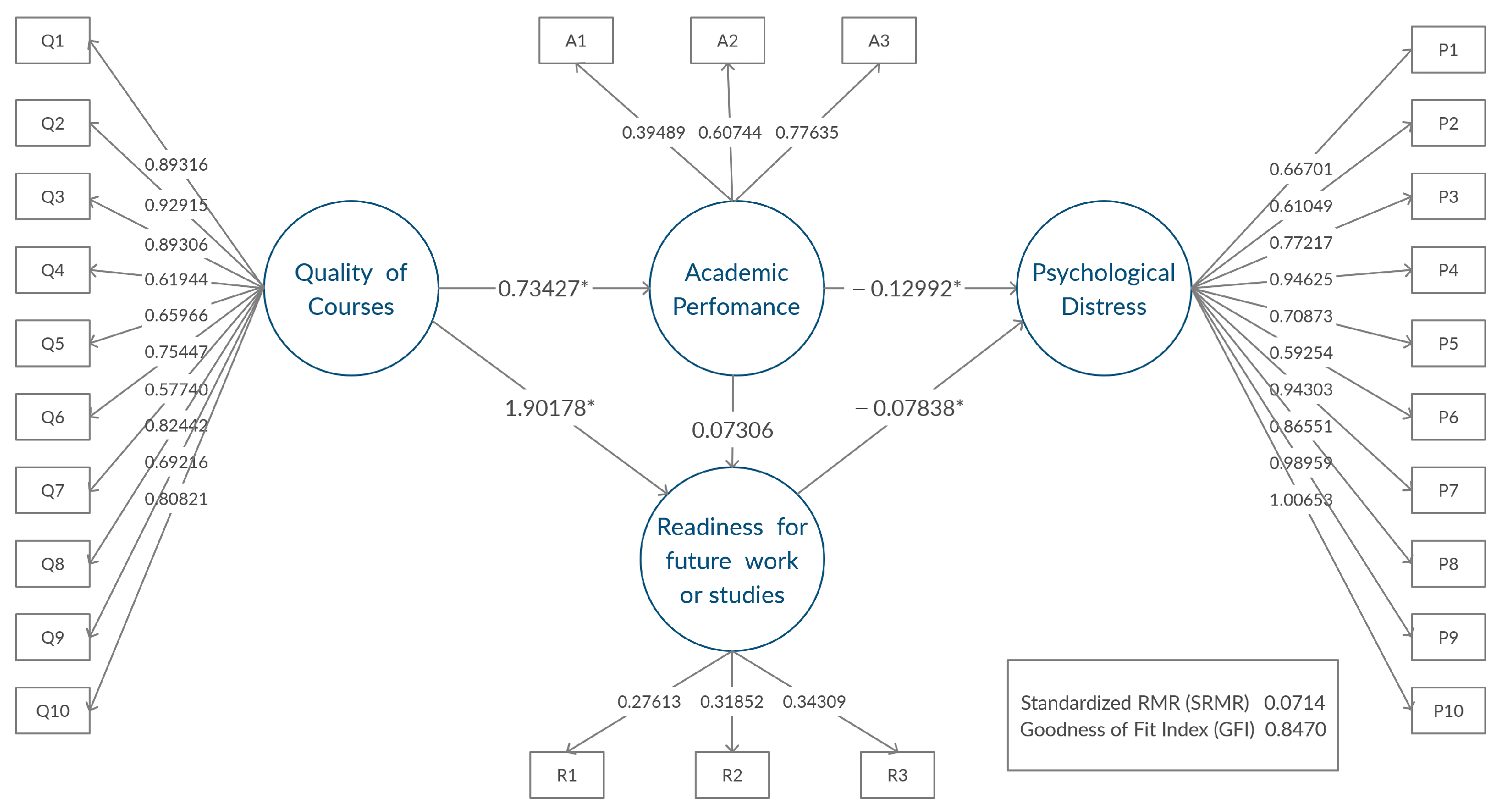

3.3.4. Multiple-Group Models

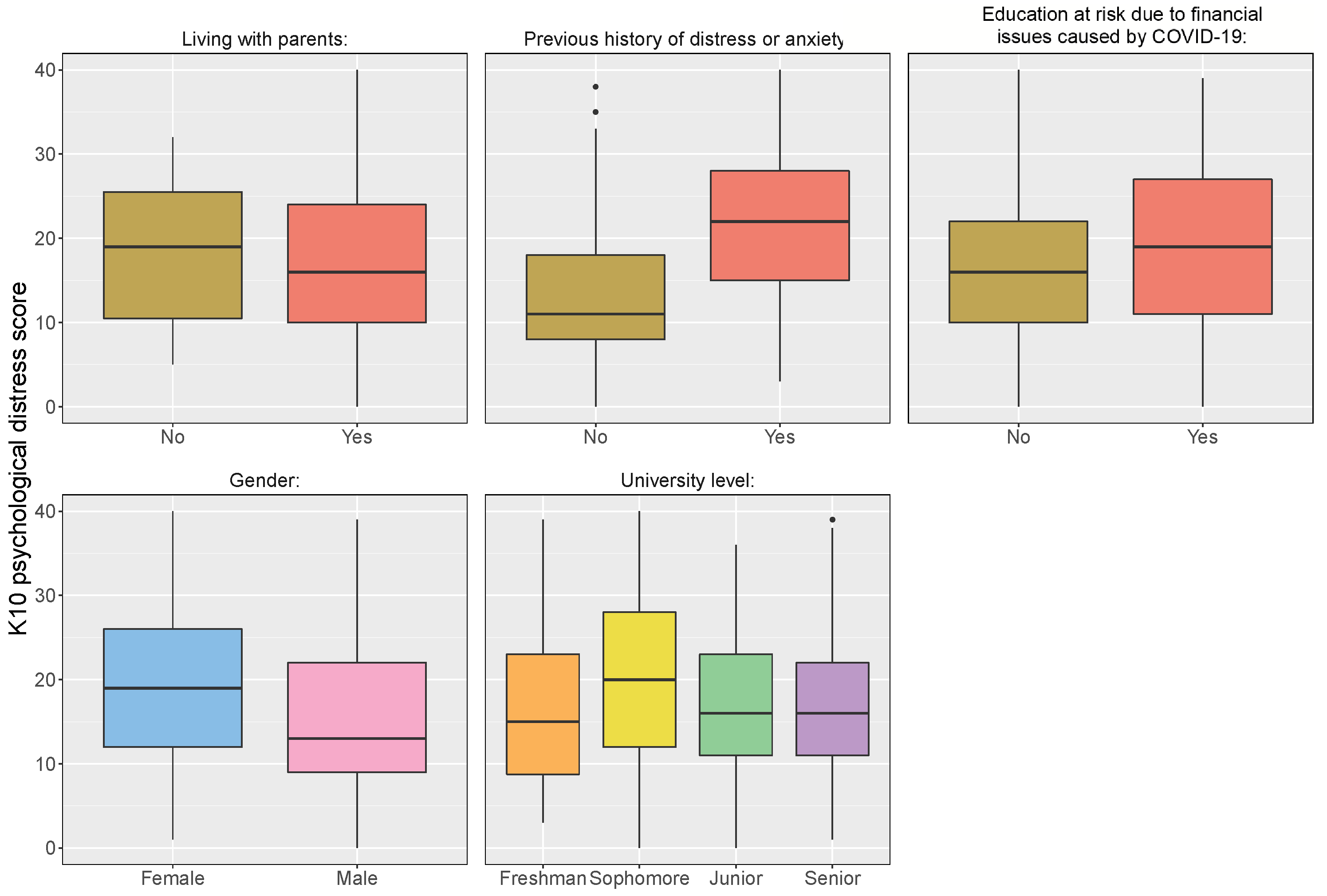

3.3.5. Univariate Statistical Tests

4. Discussion

4.1. SEM Results Discussion

4.2. Multiple-Group Models Discussion

4.3. Univariate Test Discussion

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item | Item Details |

|---|---|

| Quality of Courses | |

| Q1 | I was satisfied with the live sessions in Spring 2020. |

| Q2 | I was satisfied with the material delivery, lecture notes, and practice problems in Spring 2020. |

| Q3 | I was satisfied with the assessment components: assignments, quizzes, exams, or instructor flexibility in Spring 2020. |

| Q4 | I found the online classes to be well-organized in Spring 2020. |

| Q5 | I found the online classes to be more creative than self-study in Spring 2020. |

| Q6 | The quality of the online courses in Spring 2020 was the same as face-to-face learning. |

| Q7 | There was good interaction between me and my classmates in online classes in Spring 2020. |

| Q8 | I was satisfied with the instructors’ office hours in Spring 2020. |

| Q9 | I received feedback from the instructor regarding my work in Spring 2020. |

| Q10 | I was satisfied with the communication tools in Spring 2020: e-mails, discussion boards, Whatsapp, etc. |

| Academic Performance | |

| A1 | After Spring 2020, my GPA has (increased/decreased/remained the same). |

| A2 | I feel I have been graded fairly with respect to other students in my class in Spring 2020. |

| A3 | I feel I deserved the final grade I received in my online courses in Spring 2020. |

| Psychological Distress | |

| P1 | I often felt tired for no good reason. |

| P2 | I often felt nervous. |

| P3 | I often felt so nervous that nothing could calm me down. |

| P4 | I often felt hopeless. |

| P5 | I often felt restless or fidgety. |

| P6 | I often felt so restless that I could not sit alone. |

| P7 | I often felt depressed. |

| P8 | I often felt so sad that nothing could cheer me up. |

| P9 | I often felt worthless. |

| P10 | I often felt that everything is worthless. |

| Readiness for Future Work/Studies | |

| R1 | Online courses with labs or programming were effective in Spring 2020. |

| R2 | During Spring 2020, I learned sufficient technical knowledge to prepare me for work. |

| R3 | During Spring 2020, I learned sufficient knowledge (from pre-requisites) to prepare me for upcoming courses. |

References

- Temsah, M.H.; Al-Sohime, F.; Alamro, N.; Al-Eyadhy, A.; Al-Hasan, K.; Jamal, A.; Al-Maglouth, I.; Aljamaan, F.; Al Amri, M.; Barry, M.; et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in a MERS-CoV endemic country. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.; Peng, Z.; Guo, Y.; Rong, L.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhuang, G.; Zhang, L. Assessing the effects of metropolitan-wide quarantine on the spread of COVID-19 in public space and households. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 503–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report 82; Technical Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, I.; Mondal, A.; Antonopoulos, C.G. A SIR model assumption for the spread of COVID-19 in different communities. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 139, 110057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roma, P.; Monaro, M.; Colasanti, M.; Ricci, E.; Biondi, S.; Di Domenico, A.; Verrocchio, M.C.; Napoli, C.; Ferracuti, S.; Mazza, C. A 2-Month Follow-Up Study of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Crosta, A.; Palumbo, R.; Marchetti, D.; Ceccato, I.; La Malva, P.; Maiella, R.; Cipi, M.; Roma, P.; Mammarella, N.; Verrocchio, M.C.; et al. Individual differences, economic stability, and fear of contagion as risk factors for PTSD symptoms in the COVID-19 emergency. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, C.; Ricci, E.; Biondi, S.; Colasanti, M.; Ferracuti, S.; Napoli, C.; Roma, P. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrón, I.; Fraga, I.; Vieitez, L.; Montes, C.; Romero, E. A study on the psychological wound of COVID-19 in university students. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and Beyond (August 2020); Technical Report; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health & Prevention. UAE First Country Where Number of COVID-19 Tests Exceeded Population: Official Spokesman 2020. Available online: https://www.mohap.gov.ae/en/MediaCenter/News/Pages/2600.aspx (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- O’Keefe, L.; Rafferty, J.; Gunder, A.; Vignare, K. Delivering High-Quality Instruction Online in Response to COVID-19: Faculty Playbook; Technical Report; Online Learning Consortium: Newburyport, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: http://olc-wordpress-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2020/05/Faculty-Playbook_Final-1.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Mseleku, Z. A Literature Review of E-Learning and E-Teaching in the Era of COVID-19 Pandemic; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2020; Volume 57, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, R.M.; Abrami, P.C.; Lou, Y.; Borokhovski, E.; Wade, A.; Wozney, L.; Wallet, P.A.; Fiset, M.; Huang, B. How does distance education compare with classroom instruction? A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 379–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daniel, J. Making Sense of Flexibility as a Defining Element of Online Learning; Athabasca University: Athabasca, AB, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Amer, T. E-Learning and Education; Dar Alshehab Publication: Cairo, Egypt, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fatonia, N.A.; Nurkhayatic, E.; Nurdiawatid, E.; Fidziahe, G.P.; Adhag, S.; Irawanh, A.P.; Julyantoj, O.; Azizik, E. University Students Online Learning System During COVID-19 Pandemic: Advantages, Constraints and Solutions. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 570–576. [Google Scholar]

- Means, B.; Toyama, Y.; Murphy, R.; Bakia, M.; Jones, K. Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studies; Technical Report; Institute of Education Sciences of US Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED505824.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Shim, T.E.; Lee, S.Y. College students’ experience of emergency remote teaching due to COVID-19. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toquero, C.M. Emergency remote education experiment amid COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Res. Innov. 2020, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, T.; Knight, C.; Watermeyer, R.; Goodall, J. The impact of COVID-19 and “Emergency Remote Teaching” on the UK computer science education community. In Proceedings of the United Kingdom & Ireland Computing Education Research Conference, Glasgow, UK, 3–4 September 2020; pp. 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mohmmed, A.O.; Khidhir, B.A.; Nazeer, A.; Vijayan, V.J. Emergency remote teaching during Coronavirus pandemic: The current trend and future directive at Middle East College Oman. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2020, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.E. Global impact of COVID-19 on education systems: The emergency remote teaching at Sultan Qaboos University. J. Educ. Teach. 2020, 46, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinoni, G.; Van’t Land, H.; Jensen, T. The Impact of COVID-19 on Higher Education around the World; Technical Report; International Association of Universities: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher, A. The Impact of COVID-19 on Education: Insights from Education at a Glance 2020; Technical Report; European Union: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aucejo, E.M.; French, J.; Araya, M.P.U.; Zafar, B. The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. J. Public Econ. 2020, 191, 104271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Wang, H.Y.; Shee, D.Y. Measuring e-learning systems success in an organizational context: Scale development and validation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 1792–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navimipour, N.J.; Zareie, B. A model for assessing the impact of e-learning systems on employees’ satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 53, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nora, A.; Snyder, B.P. Technology and higher education: The impact of e-learning approaches on student academic achievement, perceptions and persistence. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. 2008, 10, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, M.; Hätönen, H.; Välimäki, M. Impact of e-learning on nurses’ and student nurses knowledge, skills, and satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanuka, H.; Kelland, J. Has e-learning delivered on its promises? Expert opinion on the impact of e-learning in higher education. Can. J. High. Educ. 2008, 38, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macgregor, G.; Turner, J. Revisiting e-learning effectiveness: Proposing a conceptual model. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2019, 6, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.H.; Shannon, D.M.; Ross, M.E. Students’ characteristics, self-regulated learning, technology self-efficacy, and course outcomes in online learning. Distance Educ. 2013, 34, 302–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.C.; Chou, C. Online learning performance and satisfaction: Do perceptions and readiness matter? Distance Educ. 2020, 41, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.; Mansour, A.E.; Fadda, W.A.; Almisnid, K.; Aldamegh, M.; Al-Nafeesah, A.; Alkhalifah, A.; Al-Wutayd, O. The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Hermida, A.P. College students’ use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2020, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhalaf, S.; Drew, S.; Alhussain, T. Assessing the impact of e-learning systems on learners: A survey study in the KSA. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 47, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsapple, C.W.; Lee-Post, A. Defining, assessing, and promoting e-learning success: An information systems perspective. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 2006, 4, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F. Measuring online learning systems success: Applying the updated DeLone and McLean model. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldholay, A.H.; Isaac, O.; Abdullah, Z.; Ramayah, T. The role of transformational leadership as a mediating variable in DeLone and McLean information system success model: The context of online learning usage in Yemen. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1421–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, E.; Murad, D.F.; Warnars, H.L.H.S.; Oktriono, K. Development Conceptual Model and Validation Instrument for E-Learning Succes Model at Universities in Indonesia: Perspectives influence of Instructor’s Activities and Motivation. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Congress on Applied Information Technology (AIT), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 4–6 November 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable. Inf. Syst. Res. 1992, 3, 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gable, G.G.; Sedera, D.; Chan, T. Re-conceptualizing information system success: The IS-impact measurement model. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2008, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, N.; Bao, Y. Impact of “e-Learning crack-up” perception on psychological distress among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: A mediating role of “fear of academic year loss”. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, F.M.; Janson, P. Can e-learning improve medical students’ knowledge and competence in paediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation? A prospective before and after study. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2010, 22, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorova, N.; Mills, A.M. Using online learning systems to improve student performance: Leveraging prior knowledge. In Learning Tools and Teaching Approaches through ICT Advancements; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Yu, C.S.; Liu, C. Learning style, learning patterns, and learning performance in a WebCT-based MIS course. Inf. Manag. 2003, 40, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parahoo, S.K.; Santally, M.I.; Rajabalee, Y.; Harvey, H.L. Designing a predictive model of student satisfaction in online learning. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2016, 26, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motiwalla, L.; Tello, S. Distance learning on the Internet: An exploratory study. Internet High. Educ. 2000, 2, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S. Assessment of learner satisfaction with asynchronous electronic learning systems. Inf. Manag. 2003, 41, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, T.; De La Rubia, M.; Hincz, K.P.; Comas-Lopez, M.; Subirats, L.; Fort, S.; Sacha, G. Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapasia, N.; Paul, P.; Roy, A.; Saha, J.; Zaveri, A.; Mallick, R.; Barman, B.; Das, P.; Chouhan, P. Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal, India. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Althunibat, A. Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 1, 5261–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aristovnik, A.; Keržič, D.; Ravšelj, D.; Tomaževič, N.; Umek, L. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala’a, B.; Akour, A.; Alfalah, L. Is it just about physical health? An Internet-based cross-sectional study exploring the psychological impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on university students in Jordan using Kessler Psychological Distress Scale. medRxiv 2020, 11, 1664-1078. [Google Scholar]

- Paechter, M.; Maier, B. Online or face-to-face? Students’ experiences and preferences in e-learning. Internet High. Educ. 2010, 13, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al Darayseh, A.S. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on modes of teaching science in UAE schools. Int. J. Med. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 11, 1844–1846. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, D.I. The Pedagogical Benefits and Pitfalls of Virtual Tools for Teaching and Learning Laboratory Practices in the Biological Sciences; Technical Report; The Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/resources/the_pedagogical_benefits_and_pitfalls_of_virtual_tools_for_teaching_and_learning_laboratory_practices_in_the_biological_sciences.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Repman, J.; Zinskie, C.; Carlson, R.D. Effective use of CMC tools in interactive online learning. Comput. Sch. 2005, 22, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Barbato, M.; Verlinden, M.; Gaspar, C.; Moussa, M.; Ghorayeb, J.; Menon, A.; Figueiras, M.J.; Arora, T.; Bentall, R.P. Psychosocial correlates of depression and anxiety in the United Arab Emirates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, C.; Mahmoud, I.; Elshami, W.; Taha, M.H. Knowledge, anxiety, fear, and psychological distress about COVID-19 among university students in the United Arab Emirates. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 582189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuraqab, N.A.S. Shall universities at the UAE continue distance learning after the COVID-19 pandemic? Revealing students’ perspective. Int. J. Adv. Res. Eng. Technol. 2020, 11, 226–233. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.L.T.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, R.B.; Sibley, S.D.; Arbaugh, J.B. A structural equation model of predictors for effective online learning. J. Manag. Educ. 2005, 29, 531–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, B.; Ordóñez, L.D.; Gilliland, S.W. Grade expectations: The effects of expectations on fairness and satisfaction perceptions. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2003, 16, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sakran, T.; Ahmed, K.; El-Sakran, A. University students’ perceptions of transfer of academic writing skills across time. J. Lang. Specif. Purp. 2017, 1, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Times Higher Education. World University Rankings. 2021. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Chan, W. Testing the difference between reliability coefficients alpha and omega. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2017, 77, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crutzen, R.; Peters, G.J.Y. Scale quality: Alpha is an inadequate estimate and factor-analytic evidence is needed first of all. Health Psychol. Rev. 2017, 11, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, O.J. Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Technometrics 1964, 6, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noteborn, G.; Dailey-Hebert, A.; Carbonell, K.B.; Gijselaers, W. Essential knowledge for academic performance: Educating in the virtual world to promote active learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2014, 37, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.F.; Werth, A.; Hoehn, J.R.; Lewandowski, H. Teaching labs during a pandemic: Lessons from Spring 2020 and an outlook for the future. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.01271. [Google Scholar]

- Perets, E.A.; Chabeda, D.; Gong, A.Z.; Huang, X.; Fung, T.S.; Ng, K.Y.; Bathgate, M.; Yan, E.C. Impact of the emergency transition to remote teaching on student engagement in a non-STEM undergraduate chemistry course in the time of COVID-19. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 2439–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartocollis, A. With Coronavirus Disrupting College, Should Every Student Pass? The New York Times: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sohail, N. Stress and academic performance among medical students. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2013, 23, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- The National. Distance Learning in UAE: Free Mobile Internet for Families without Home WiFi. Available online: https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/government/distance-learning-in-uae-free-mobile-internet-for-families-without-home-wifi-1.994440 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Vd Westhuizen, D. Guidelines for Online Assessment for Educators; Technical Report; Commonwealth of Learning: Burnaby, BC, Canada, 2016; Available online: https://engineering.utm.my/computing/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/04/Guidelines-Online-Assessment.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Rahim, A.F.A. Guidelines for online assessment in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Med. J. 2020, 12, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloxham, S.; Boyd, P. Developing Effective Assessment in Higher Education: A Practical Guide; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M.; Salamonson, Y.; Metcalfe, L. Student engagement using multiple-attempt ‘Weekly Participation Task’quizzes with undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 46, 102803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quality Matters. QM Emergency Remote Instruction Checklist. Available online: https://www.qualitymatters.org/qa-resources/resource-center/articles-resources/ERI-Checklist (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Iglesias-Pradas, S.; Hernández-García, Á.; Chaparro-Peláez, J.; Prieto, J.L. Emergency remote teaching and students’ academic performance in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelles, L.A.; Lord, S.M.; Hoople, G.D.; Chen, D.A.; Mejia, J.A. Compassionate flexibility and self-discipline: Student adaptation to emergency remote teaching in an integrated engineering energy course during COVID-19. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, B.; Gachago, D.; Belford, C. To care or not to care–reflections on the ethics of blended learning in times of disruption. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2018, 32, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Means, B.; Neisler, J. Suddenly Online: A National Survey of Undergraduates during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Technical Report; Digital Promise: San Mateo, CA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED610781.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Walsh, L.L.; Arango-Caro, S.; Wester, E.R.; Callis-Duehl, K. Training faculty as an institutional response to COVID-19 Emergency Remote Teaching supported by data. Life Sci. Educ. 2021, 20, ar34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, C.A.; Ewing, L.; Heath, N.L.; Goldstein, A.L. When social isolation is nothing new: A longitudinal study psychological distress during COVID-19 among university students with and without preexisting mental health concerns. Can. Psychol. Can. 2020, 62, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American University of Sharjah. Undergraduate Catalog 2020–2021; American University of Sharjah: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza, C.; Ricci, E.; Marchetti, D.; Fontanesi, L.; Di Giandomenico, S.; Verrocchio, M.C.; Roma, P. How personality relates to distress in parents during the COVID-19 lockdown: The mediating role of child’s emotional and behavioral difficulties and the moderating effect of living with other people. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, C.E.; Zhu, H.; Marquez Kiyama, J. Parents and families of first-generation college students experience their own college transition. J. High. Educ. 2020, 91, 540–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, A.; Gorwood, P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Galea, S.; Merchant, R.M.; Lurie, N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Dimension | Najmul and Yukun [46] | Kapasia et al. [54] | Cao et al. [55] | Almaiah et al. [56] | Aucejo et al. [27] | Aristovnik et al. [57] | Al-Tammemi et al. [58] | Aguilera-Hermida [37] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of ERT | ||||||||

| 1-Finding the course clumsy | X | X | X | |||||

| 3-Task performance and engagement | X | X | ||||||

| 4-Performance feedback | X | X | ||||||

| 5-Instructor Support | X | X | X | |||||

| 6-Online assessment | X | |||||||

| 7-Interaction with peer students | X | X | ||||||

| Learning conditions | ||||||||

| 1-Study Habits | X | X | X | |||||

| 2-Learning environment | X | X | ||||||

| 3-Motivation for study | X | X | X | |||||

| Technological ease | ||||||||

| 1-Access to the internet/technology | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 2-Availability of technical assistance | X | X | ||||||

| 2-Ease of online procedures | X | X | X | |||||

| Student fears | ||||||||

| 1-Worry about academic delays | X | X | X | |||||

| 2-Worry about career development | X | |||||||

| 3-Worry about public examinations | X | X | ||||||

| 4-Worry about academic year decision | X | |||||||

| 5-Worry about future studies | X | |||||||

| 6-Fear of losing academic year | X | |||||||

| Financial issues | ||||||||

| 1-Steady family income | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 2-E-Learning costs | X | |||||||

| Mental health | ||||||||

| 1-Previous history of mental health challenges | X | |||||||

| 2-Feelings of anxiety or depression | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 3-GAD7 (Anxiety levels) | X | |||||||

| 4-K10 (Kessler Psychological Distress) | X | X |

| Demographic Information | Response | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1. Female | 324 | 55.10% |

| 2. Male | 264 | 44.90% | |

| Year of study | 1. Freshman | 160 | 27.20% |

| 2. Sophomore | 179 | 30.40% | |

| 3. Junior | 94 | 16.00% | |

| 4. Senior | 155 | 26.40% | |

| Living with Parents | 1. No | 35 | 5.90% |

| 2. Yes | 553 | 94.0% | |

| Education at risk due to financial issues caused by COVID-19 | 1. No | 342 | 58.20% |

| 2. Yes | 246 | 41.80% | |

| Previous history of distress or anxiety | 1. No | 283 | 48.10% |

| 2. Yes | 305 | 51.90% |

| Factors | Correlation with Total | Cronbach’s Alpha | McDonald’s Omega |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Distress | 0.913 | 0.914 | |

| P1 | 0.643 | ||

| P2 | 0.601 | ||

| P3 | 0.695 | ||

| P4 | 0.751 | ||

| P5 | 0.621 | ||

| P6 | 0.542 | ||

| P7 | 0.780 | ||

| P8 | 0.737 | ||

| P9 | 0.713 | ||

| P10 | 0.738 | ||

| Academic Performance | 0.622 | 0.678 | |

| A1 | 0.317 | ||

| A2 | 0.435 | ||

| A3 | 0.557 | ||

| Quality of Courses | 0.882 | 0.883 | |

| Q1 | 0.702 | ||

| Q2 | 0.739 | ||

| Q3 | 0.684 | ||

| Q4 | 0.515 | ||

| Q5 | 0.546 | ||

| Q6 | 0.596 | ||

| Q7 | 0.493 | ||

| Q8 | 0.607 | ||

| Q9 | 0.576 | ||

| Q10 | 0.642 | ||

| Readiness for Future Work/Studies | 0.640 | 0.659 | |

| R1 | 0.420 | ||

| R2 | 0.530 | ||

| R3 | 0.410 |

| Path | Estimate | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | Standardized Estimate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P => P1 | 0.68726 | <0.0001 | 0.60996 | 0.76455 | 0.66762 |

| P => P2 | 0.63511 | <0.0001 | 0.54977 | 0.72045 | 0.57962 |

| P => P3 | 0.79095 | <0.0001 | 0.70369 | 0.87821 | 0.67789 |

| P => P4 | 0.96220 | <0.0001 | 0.87927 | 1.04512 | 0.81126 |

| P => P5 | 0.72062 | <0.0001 | 0.63300 | 0.80824 | 0.62821 |

| P => P6 | 0.60237 | <0.0001 | 0.51296 | 0.69178 | 0.5329 |

| P => P7 | 0.94348 | <0.0001 | 0.86286 | 1.02409 | 0.81755 |

| P => P8 | 0.87302 | <0.0001 | 0.79064 | 0.95540 | 0.76493 |

| P => P9 | 1.00049 | <0.0001 | 0.90509 | 1.09588 | 0.75809 |

| P => P10 | 1.01884 | <0.0001 | 0.92564 | 1.11205 | 0.78006 |

| A => A1 | 0.39055 | <0.0001 | 0.29959 | 0.48151 | 0.39705 |

| A => A2 | 0.60584 | <0.0001 | 0.52054 | 0.69113 | 0.67014 |

| A => A3 | 0.76181 | <0.0001 | 0.65890 | 0.86471 | 0.77278 |

| Q => Q1 | 0.89628 | <0.0001 | 0.80809 | 0.98446 | 0.73612 |

| Q => Q2 | 0.92582 | <0.0001 | 0.84214 | 1.00950 | 0.78004 |

| Q => Q3 | 0.89197 | <0.0001 | 0.80582 | 0.97812 | 0.74287 |

| Q => Q4 | 0.61865 | <0.0001 | 0.52779 | 0.70950 | 0.53454 |

| Q => Q5 | 0.65395 | <0.0001 | 0.56498 | 0.74291 | 0.56999 |

| Q=> Q6 | 0.74931 | <0.0001 | 0.65980 | 0.83883 | 0.63314 |

| Q => Q7 | 0.57746 | <0.0001 | 0.49155 | 0.66336 | 0.52874 |

| Q => Q8 | 0.82296 | <0.0001 | 0.72899 | 0.91692 | 0.65594 |

| Q => Q9 | 0.68880 | <0.0001 | 0.60502 | 0.77257 | 0.62425 |

| Q => Q10 | 0.80383 | <0.0001 | 0.71950 | 0.88815 | 0.69946 |

| R => R1 | 0.27442 | <0.0001 | 0.19426 | 0.35458 | 0.48133 |

| R => R2 | 0.31450 | <0.0001 | 0.22922 | 0.39978 | 0.61838 |

| R => R3 | 0.34260 | <0.0001 | 0.25051 | 0.43469 | 0.70998 |

| Effect | Path | Estimate | SE | p-Value | Std. Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | Quality of Courses =>Academic Performance | 0.7519 | 0.0756 | <0.0001 | 0.6009 |

| Quality of Courses =>Readiness for Future Work/Studies | 1.9019 | 0.2960 | <0.0001 | 0.8648 | |

| Academic Performance =>Psychological Distress | −0.1392 | 0.0570 | 0.0146 | −0.1672 | |

| Readiness for Future Work/Studies =>Psychological Distress | −0.0701 | 0.0319 | 0.0281 | −0.1480 | |

| Academic Performance =>Readiness for Future Work/Studies | 0.0737 | 0.1075 | 0.4929 | 0.0419 | |

| Indirect Effects | Quality of Courses =>Psychological Distress | −0.2418 | 0.0455 | <0.0001 | −0.2322 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El-Sakran, A.; Salman, R.; Alzaatreh, A. Impacts of Emergency Remote Teaching on College Students Amid COVID-19 in the UAE. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052979

El-Sakran A, Salman R, Alzaatreh A. Impacts of Emergency Remote Teaching on College Students Amid COVID-19 in the UAE. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052979

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl-Sakran, Alaa, Reem Salman, and Ayman Alzaatreh. 2022. "Impacts of Emergency Remote Teaching on College Students Amid COVID-19 in the UAE" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052979

APA StyleEl-Sakran, A., Salman, R., & Alzaatreh, A. (2022). Impacts of Emergency Remote Teaching on College Students Amid COVID-19 in the UAE. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052979