ARCCH Model of Resilience: A Flexible Multisystemic Resilience Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Trauma

1.2. Resilience

1.3. Attachment, Regulation, and Competence Framework

1.4. Importance of Addressing Culture in a Resilience Framework

1.4.1. Cultural Identities

1.4.2. Cultural Context

1.5. Importance of Addressing Health in a Resilience Framework

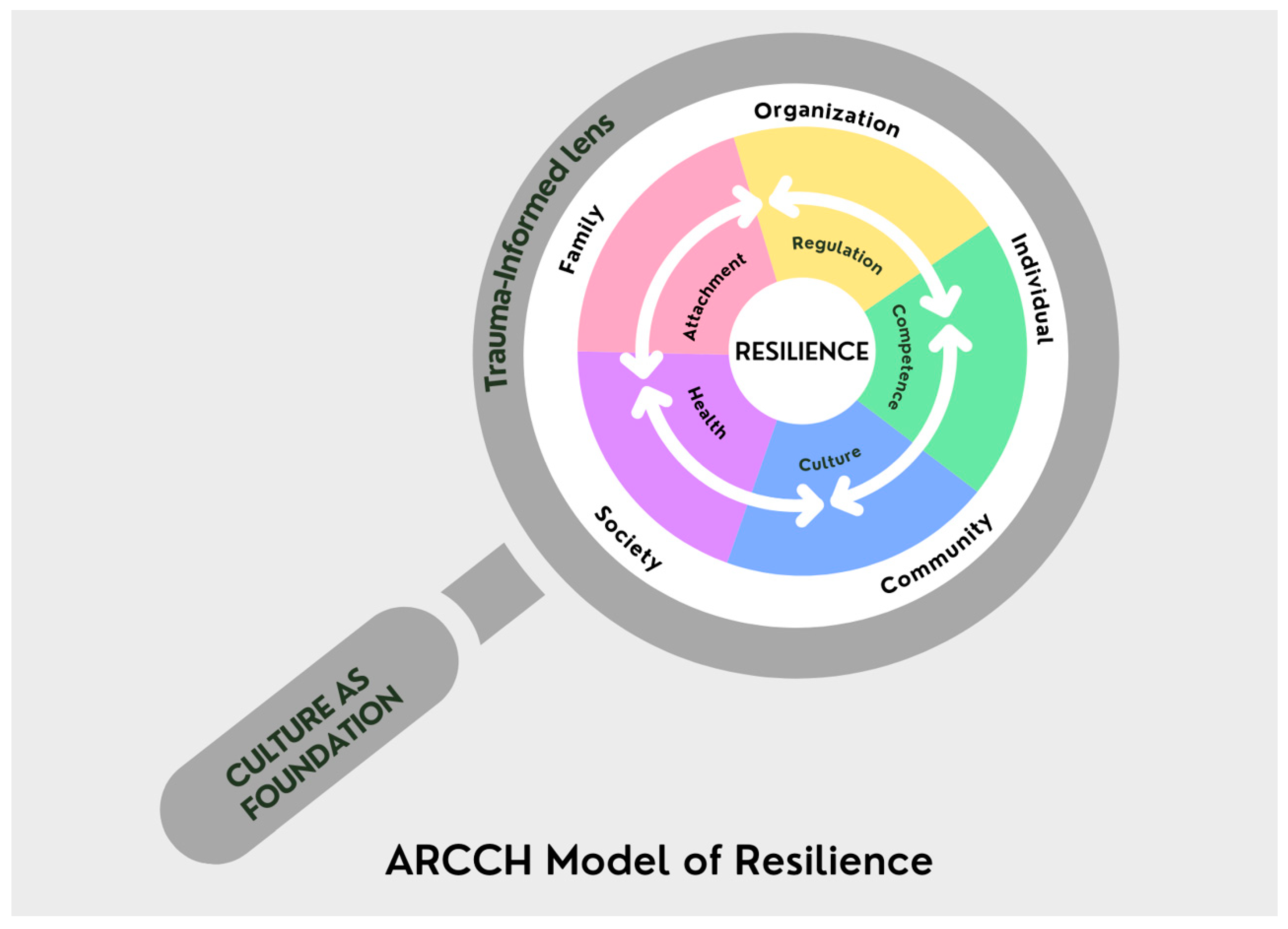

2. The ARCCH Model of Resilience: An Expanded Conceptual Framework

2.1. The ARCCH Model of Resilience—Conceptual Model

2.2. Definitions Underlying the ARCCH Model of Resilience

2.2.1. Attachment

2.2.2. Regulation

2.2.3. Competence

2.2.4. Culture

2.2.5. Health

2.2.6. System

2.3. Assumptions Underlying the ARCCH Model of Resilience

2.3.1. Interconnection between ARCCH and Systems

2.3.2. Strengths-Based Model

2.3.3. The ARCCH Model of Resilience Is a Flexible Model

2.3.4. Multisystemic View

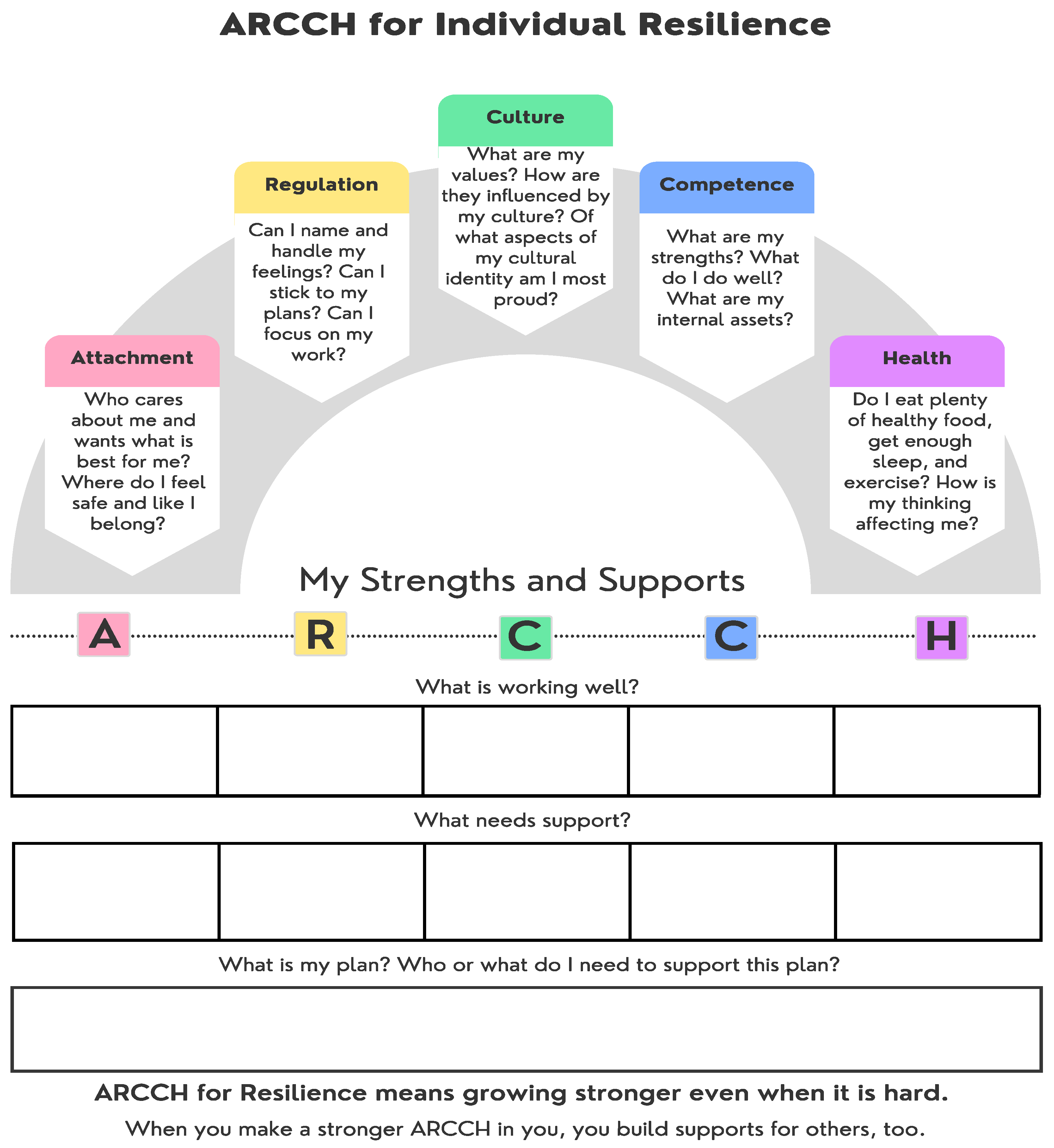

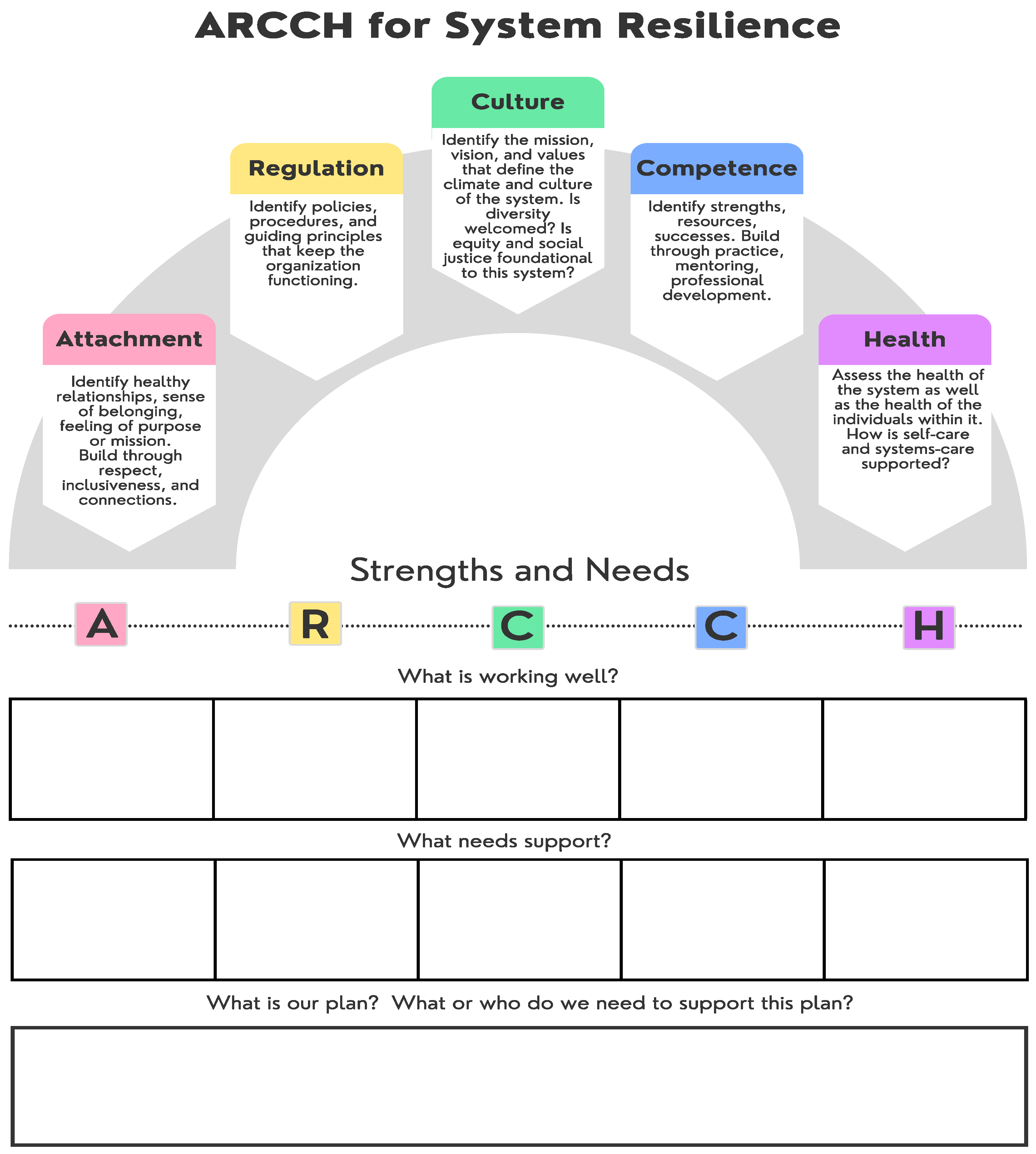

2.4. How to Use the ARCCH Model of Resilience

2.5. Fictional Vignette Showing Strengths and Need for Support Using the ARCCH Model

2.5.1. ARCCH for Individual (Zevin)

2.5.2. ARCCH for the Family

2.5.3. ARCCH for Community

2.5.4. ARCCH for the System

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. REPRINT OF: Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Author. 2014. Available online: https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hardcastle, K.A.; Sethi, D.; Butchart, A.; Mikton, C.; Jones, L.; Dunne, M.P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Danese, A.; McEwen, B.S. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 106, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cronholm, P.F.; Forke, C.M.; Wade, R.; Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Davis, M.; Harkins-Schwartz, M.; Pachter, L.M.; Fein, J.A. Adverse Childhood Expereince: Expanding the concept of adversity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, V.; Murphey, D. The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences, Nationally, by State, and by Race or Ethnicity. Center for Victim Research Repository, 2018. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11990/1142 (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Bernard, D.L.; Calhoun, C.D.; Banks, D.E.; Halliday, C.A.; Hughes-Halbert, C.; Danielson, C.K. Making the “C-ACE” for a Culturally-Informed Adverse Childhood Experiences Framework to Understand the Pervasive Mental Health Impact of Racism on Black Youth. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2021, 14, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungar, M.; Theron, L.; Murphy, K.; Jefferies, P. Researching Multisystemic Resilience: A Sample Methodology. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F.R.L.; Baker, K.L.; Burrell, J. Introducing the skills-based model of personal resilience: Drawing on content and process factors to build resilience in the workplace. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 94, 458–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurović, I.; Liebenberg, L.; Ferić, M. A review of family resilience: Understanding the concept and operationaliza-tion challenges to inform research and practice. Child Care Pract. 2020, 26, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, W.R.; Dietz, W.H. A New Framework for Addressing Adverse Childhood and Community Experiences: The Building Community Resilience Model. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, S86–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Milken Institute School of Public Health. Building Community Resilience: Coalition Building and Communications Guide. March 2017. Available online: https://publichealth.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/downloads/Redstone-Center/BCR%20Coalition%20Building%20and%20Communications%20Guide.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- Masten, A.S.; Lucke, C.M.; Nelson, K.M.; Stallworthy, I.C. Resilience in development and psychopathology: Multisystem perspectives. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 17, 521–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, H.E.; Johnson, D.J.; Allen, J.; Villarruel, F.A.; Qin, D.B. Historical and race-based trauma: Rsilience through family and community. Advers. Resil. Sci. 2021, 2, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kinniburgh, K.; Blaustein, M. Attachment, self-regulation, and competence: A comprehensive framework for intervention with complexly traumatized youth. A treatment manual. Psychiatr. Ann. 2005, 35, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kinniburgh, K.J.; Blaustein, M.; Spinazzola, J.; van der Kolk, B.A. Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency: A comprehensive intervention framework for children with complex trauma. Psychiatr. Ann. 2005, 35, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blaustein, M.; Kinniburgh, K. Treating Traumatic Stress in Children and Adolescents: How to Foster Resilience through Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competence; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.D.; Blaustein, M.E. Systemic Self-Regulation: A Framework for Trauma-Informed Services in Residential Juvenile Justice Programs. J. Fam. Violence 2013, 28, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brend, D.; Fréchette, N.; Milord-Nadon, A.; Harbinson, T.; Collin-Vezina, D. Implementing trauma-informed care through social innovation in residential care facilities serving elementary school children. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Resil. 2020, 7, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgdon, H.B.; Kinniburgh, K.; Gabowitz, D.; Blaustein, M.E.; Spinazzola, J. Development and Implementation of Trauma-Informed Programming in Youth Residential Treatment Centers Using the ARC Framework. J. Fam. Violence 2013, 28, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgdon, H.B.; Blaustein, M.; Kinniburgh, K.; Peterson, M.L.; Spinazzola, J. Application of the ARC Model with Adopted Children: Supporting Resiliency and Family Well Being. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2016, 9, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, J.S.; Martinez, M.; McArthur, L.E.; Leibovitz, T. Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS): A Whole-School, Multi-level, Prevention and Intervention Program for Creating Trauma-Informed, Safe and Supportive Schools. Sch. Ment. Health 2016, 8, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidson, J.; Kinniburgh, K.; Howard, K.; Spinazzola, J.; Strothers, H.; Evans, M.; Andres, B.; Cohen, C.; Blaustein, M.E. Treatment of Complex Trauma in Young Children: Developmental and Cultural Considerations in Application of the ARC Intervention Model. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2011, 4, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton-Anderson, J.N.; Carter, S.; Fani, N.; Gillespie, C.F.; Henry, T.L.; Holmes, E.; Lamis, D.A.; LoParo, D.; Maples-Keller, J.L.; Powers, A.; et al. Adverse childhood experiences in African Americans: Framework, practice, and policy. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, F.T.; Howard, T.C.; Langley, A.K. Understanding and addressing racial stress and trauma in schools: A pathway toward resistance and healing. Psychol. Sch. 2021, 3, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association, APA Task Force on Race and Ethnicity Guidelines in Psychology. Race and Ethnicity Guidelines in Psychology: Promoting Responsiveness and Equity. 2019. Available online: https://www.apa.org/about/policy/race-and-ethnicity-in-psychology.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Henfield, M.; Washington, A.R.; Besirevic, Z.; De La Rue, L. Introduction to Trauma-Informed Practices for Mental Health and Wellness in Urban Schools and Communities. Urban Rev. 2019, 51, 537–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scrine, E. The Limits of Resilience and the Need for Resistance: Articulating the Role of Music Therapy with Young People within a Shifting Trauma Paradigm. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 600245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Slopen, N.; Williams, D.R. Early Childhood Adversity, Toxic Stress, and the Impacts of Racism on the Foundations of Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrone, R.; Stanton, C.R. From producing to reducing trauma: A call for “trauma-informed” research (ers) to in-terrogate how schools harm students. Educ. Res. 2021, 50, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/about.html (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Johnson, S.R. Kaiser Pledges $2.75 Million to Research Childhood Trauma. Online Newsource Retrieved 4 December 2019. Available online: https://www.modernhealthcare.com/providers/kaiser-pledges-275-million-research-childhood-trauma (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Metzler, M.; Merrick, M.T.; Klevens, J.; Ports, K.A.; Ford, D.C. Adverse childhood experiences and life opportunities: Shifting the narrative. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 72, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merrick, J.S.; Narayan, A.J.; DePasquale, C.E.; Masten, A.S. Benevolent Childhood Experiences (BCEs) in homeless parents: A validation and replication study. J. Fam. Psycho. 2019, 33, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungar, M. (Ed.) Modeling multisystemic resilience: Connecting biological, psychological, social, and ecological adaptation in contexts of adversity. In Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 6–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff, J.P. Capitalizing on Advances in Science to Reduce the Health Consequences of Early Childhood Adversity. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomason, M.E.; Marusak, H.A. Toward understanding the impact of trauma on the early developing human brain. Neuroscience 2017, 342, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Banyard, V.; Hamby, S.; Grych, J. Health effects of adverse childhood events: Identifying promising protective factors at the intersection of mental and physical well-being. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 65, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Portilla, X.A.; Ballard, P.J.; Adler, N.E.; Boyce, W.T.; Obradović, J. An Integrative View of School Functioning: Transactions between Self-Regulation, School Engagement, and Teacher-Child Relationship Quality. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 1915–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berástegui, A.; Pitillas, C. What does it take for early relationships to remain secure in the face of adversity? At-tachment as a unit of resilience. In Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change; Ungar, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, M.; Fosco, G.M.; Feinberg, M.E. Examining reciprocal influences among family climate, school attachment, and academic self-regulation: Implications for school success. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.M.; Baker, C.N.; Wilcox, P. Risking connection trauma training: A pathway toward trauma-informed care in child congregate care settings. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2012, 4, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Townley, C. Inclusion, belonging and intercultural spaces: A narrative policy analysis of playgroups in Australia. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2021, 10, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalera-Reyes, J. Place Attachment, Feeling of Belonging and Collective Identity in Socio-Ecological Systems: Study Case of Pegalajar (Andalusia-Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anyon, Y.; Atteberry-Ash, B.; Yang, J.; Pauline, M.; Wiley, K.; Cash, D.; Downing, B.; Greer, E.; Pisciotta, L. It’s All about the Relationships”: Educators’ Rationales and Strategies for Building Connections with Students to Prevent Exclusionary School Discipline Outcomes. Child. Sch. 2018, 40, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theron, L. Learning about systemic resilience from studies of student resilience. In Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change; Ungar, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo, P.D.; Blair, C.B.; Willoughby, M.T. Executive Function: Implications for Education (NCER 2017–2000); National Center for Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: http://ies.ed.gov/ (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Hambrick, E.P.; Brawner, T.W.; Perry, B.D.; Brandt, K.; Hofmeister, C.; Collins, J.O. Beyond the ACE score: Examining relationships between timing of developmental adversity, relational health and developmental outcomes in children. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 33, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anda, R.F.; Fleisher, V.I.; Felitti, V.J.; Edwards, V.J.; Whitfield, C.L.; Dube, S.R.; Williamson, D.F. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and indicators of impaired adult worker performance. Perm. J. 2004, 8, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunzell, T.; Stokes, H.; Waters, L. Trauma-Informed Positive Education: Using Positive Psychology to Strengthen Vulnerable Students. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2016, 20, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blitz, L.; Yull, D.; Clauhs, M. Bringing Sanctuary to School: Assessing School Climate as a Foundation for Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Approaches for Urban Schools. Urban Educ. 2016, 55, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, S.L. Creating Sanctuary: Toward the Evolution of Sane Societies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciak, A.S.; Powers, J.; Medberry, L. Schoolwide trauma informed professional development: We Can! Building Relationships and Resilience. In Alleviating the Educational Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences: School-University-Community Collaboration; Reardon, M., Leonard, J., Eds.; Current Perspectives on School/University/Community Research; Information Age Publishing, Inc.: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2020; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Howse, R.B.; Lange, G.; Farran, D.C.; Boyles, C.D. Motivation and Self-Regulation as Predictors of Achievement in Economically Disadvantaged Young Children. J. Exp. Educ. 2003, 71, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxer, J.L.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation in teachers: The “why” and “how”. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 74, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijde, C.M. Employability and Self-Regulation in Contemporary Careers. In Psycho-Social Career Meta-Capacities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Day-Vines, N.L.; Cluxton-Keller, F.; Agorsor, C.; Gubar, A. Strategise for Broaching the subjects of race, ethnicity, and culture. J. Couns. Dev. 2021, 99, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day-Vines, N.L.; Wood, S.M.; Grothaus, T.; Craigen, L.; Holman, A.; Dotson-Blake, K.; Douglass, M.J. Broaching the Subjects of Race, Ethnicity, and Culture During the Counseling Process. J. Couns. Dev. 2007, 85, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.M.; Anderson, L.A.; Notice, M.R. Revisioning the Concept of Resilience: Its Manifestation and Impact on Black Americans. Int. J. Fam. Ther. 2022, 44, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, R.; Shea, J.A.; Rubin, D.; Wood, J.; Coker, T.R.; Moreno, C.; Shekelle, P.G.; Schuster, M.A.; Chung, P.J. Adverse Childhood Experiences of Low-Income Urban Youth. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e13–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, L. Building an organization that promotes healing, well-being, and resilience. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2021, 27, 336–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, H.; Jones, M.S.; Gibbs, B.G. Early adverse childhood experiences and exclusionary discipline in high school. Soc. Sci. Res. 2022, 101, 102621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, M. Family Therapy in Clinical Practice; Jason Aronson: Lanham, MD, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti, D. Resilience under conditions of extreme stress: A multilevel perspective. World Psychiatry 2010, 9, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schomerus, G.; Schindler, S.; Rechenberg, T.; Gfesser, T.; Grabe, H.J.; Liebergesell, M.; Sander, C.; Ulke, C.; Speerforck, S. Stigma as a barrier to addressing childhood trauma in conversation with trauma survivors: A study in the general population. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S. Resilience in developing systems: The promise of integrated approaches. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 13, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gott, J.; Lang, P. The school: The front line of mental health development. Pastor. Care Educ. 2003, 21, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothì, D.M.; Leavey, G.; Best, R. On the front-line: Teachers as active observers of pupils’ mental health. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 1217–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Steps | What to Assess/Ask Questions About | Information and/or Potential Questions/Prompts to Consider |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Identify the setting and cultural context that ARCCH will be applied | The facilitator should first do their own homework to gather whatever information they can prior to the first meeting. Is there something about the organization that is important to understand? Are there historical traumas that are present? One should not expect whomever is the focus of support to teach them the foundation. Instead, the facilitator’s job is to help to understand the nuances for each person(s) involved through the conversation. |

| Step 2 | Identify who the focus of support is: the individual, family, community, or system | Depending upon how the connection was made, this may be obvious. However, it is important to consider the interconnection of individuals, families, communities, and systems. Whomever may be the focus at the start of the conversation or support may not be the sole area of focus. The flexibility to move between all involved and to see it from a systemic perspective will be valuable. |

| Step 3 | Identify the strengths of whomever is the focus of the support | Individual Attachment: Can you tell me who you are closest to? What is it about that person that helps you feel close to them? Family Culture: I would be curious to learn from each of you what aspects of your family’s culture and background provides you with greatest sense of pride? |

| Step 4 | Identify what areas are in need of support | System Regulation: I know that within organizations there are a lot of moving parts and often a lot of expertise about ways in which things can be improved upon. Could you each tell me a little bit about areas within your policies and procedures you would like to see improved? |

| Step 5 | Once areas of strength and support are identified then you can collaboratively create small manageable steps to build support each area. Please see Appendix A and Appendix B to help facilitate conversation. | It is important to note that it may not seem feasible in the first or even after multiple conversations to feel like you have a solid plan of support for each area. Please know it is ok to focus on one area for the time it needs. Then once someone is feeling confident in that area, it could be possible to build off that into another area of the ARCCH components. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wojciak, A.S.; Powers, J.; Chan, A.C.Y.; Pleggenkuhle, A.L.; Hooper, L.M. ARCCH Model of Resilience: A Flexible Multisystemic Resilience Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3920. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073920

Wojciak AS, Powers J, Chan ACY, Pleggenkuhle AL, Hooper LM. ARCCH Model of Resilience: A Flexible Multisystemic Resilience Framework. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):3920. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073920

Chicago/Turabian StyleWojciak, Armeda Stevenson, Jan Powers, Athena Chung Yin Chan, Allison L. Pleggenkuhle, and Lisa M. Hooper. 2022. "ARCCH Model of Resilience: A Flexible Multisystemic Resilience Framework" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 3920. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073920

APA StyleWojciak, A. S., Powers, J., Chan, A. C. Y., Pleggenkuhle, A. L., & Hooper, L. M. (2022). ARCCH Model of Resilience: A Flexible Multisystemic Resilience Framework. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3920. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073920