Abstract

Digital health interventions (DHIs) are increasingly used to address the health of migrants and ethnic minorities, some of whom have reduced access to health services and worse health outcomes than majority populations. This study aims to give an overview of digital health interventions developed for ethnic or cultural minority and migrant populations, the health problems they address, their effectiveness at the individual level and the degree of participation of target populations during development. We used the methodological approach of the scoping review outlined by Tricco. We found a total of 2248 studies, of which 57 were included, mostly using mobile health technologies, followed by websites, informational videos, text messages and telehealth. Most interventions focused on illness self-management, mental health and wellbeing, followed by pregnancy and overall lifestyle habits. About half did not involve the target population in development and only a minority involved them consistently. The studies we found indicate that the increased involvement of the target population in the development of digital health tools leads to a greater acceptance of their use.

1. Introduction

Digital technologies such as mobile apps, text messaging and wearable devices represent an increasingly large field in health, promising to deliver individualized health care to a wide public. Numerous studies, however, have shown that digital health care is not equally distributed and disadvantages already vulnerable groups, thus sustaining or increasing existing health disparities [1,2,3,4,5]. Initial studies analyzing equity within digital interventions looked at whether disadvantaged groups such as minorities or migrants are less likely to use digital interventions. They found that smartphone and digital device use is also widespread among these groups [6,7] and that there is increasing openness to the use of digital health interventions and health information seeking using mobile devices [6,8]. However, studies have shown that health apps are rarely tailored to disadvantaged communities, although the degree of community-engagement in the development of health apps is key for usability and adherence [9].

In technology development, the involvement of potential users plays an important role. To implement this, there are various models, for example user-centered design (UCD) [10] and participatory design (PD) [11]. UCD starts from the needs of the users and involves them throughout the technology development process. PD starts earlier than UCD and collects user needs before product development. In addition to this, PD focuses on “human action and people’s rights to participate in the shaping of the worlds in which they act”, with participation focusing on “the fundamental transcendence of the users’ role from being merely informants to being legitimate and acknowledged participants in the design process” (pp. 4–5 [11]). End users can create content and make decisions (about features and appearance). In contrast to UCD, PD views potential users as partners and involves them in the entire technology development process. Therefore, in this scoping review we will be focusing closely on migrants and ethnic or cultural minorities and the development of Digital Health Interventions (DHI) for and with these communities. We use the term DHIs to refer to digital technology that is applied to achieve health goals [12]. Their range is broad and can reach from electronic medical records to mobile health apps used [13]. We will be looking at the level of participation or co-design, in the development of digital interventions and how it influences the outcomes, usability and adherence of the DHIs. Our hypothesis is that higher participation will lead to a more nuanced and targeted design, as well as to better health outcomes and more widespread use of the digital intervention.

In this study, we are using Lai et al.’s (p. 758 [14]) definition of migrants “as persons residing in a country who were born outside of that country and who arrived through an immigration or refugee program” [14]. Ethnic or cultural minorities are defined as persons which constitute “less than half of the population of the entire territory of a state whose members share common characteristics of culture, religion of language, or a combination of any of these.” [15]. Minority status is different from migrant or citizenship status as members of ethnic or cultural minorities can be citizens or non-citizens [14]. Furthermore, ethnic or cultural minorities include White, Black, Latino, Indigenous, Asian, Middle-Eastern and other minorities [16]. These groups are not homogenous, but face “similar challenges in terms of integration (…) related to discrimination, health status, civic engagement, and employment” (pp. 63–66 [14]). The terms “ethnic” and “cultural” minority are often used interchangeably in studies, sometimes in combination (“ethno-cultural” minorities). We will consistently be using both terms.

In this scoping review we want to analyze which digital health tools have been developed specifically for this diverse population, what health conditions or aspects of wellbeing they tackle and what the outcomes of their use are. We particularly aimed to map the degree of participation of the target groups in the identified studies and discuss its implication for the successful uptake of digital health technologies and actual impact on health outcomes.

2. Materials and Methodology

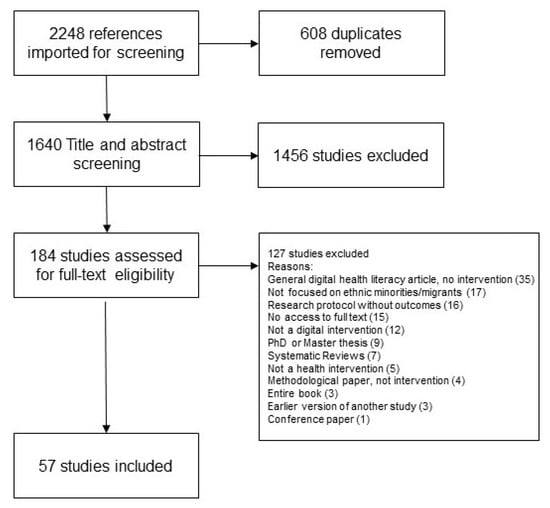

We chose the methodological approach of the scoping review because the literature in the field of digital health interventions for minority/migrant groups is very heterogenous. Scoping reviews are particularly useful to “identify main concepts, theories and knowledge gaps” (p. 467 [17]) in fields where few overview studies or systematic reviews exist. Our scoping review aims to provide a focus on the digital health interventions developed for minority and migrant groups, the health problems they address, their effectiveness at the individual level and the level of participation of the target groups in the development. We follow the methodology outlined by Tricco [17] and Arksey and O’Malley [18]. This means all steps and results of the search were documented and reported following the PRISMA Extension for Scoping reviews (PRIMSA-SCr) Checklist (see Figure 1).

2.1. Defining Relevant Terms

The initial keywords were digital tools, migration, user groups and health care. The search strategy using all identified key words can be found under the search term overview which was published at the Open Society Foundation (OSF) [19].

2.2. Searching and Identifying Relevant Studies

The studies were identified through a systematic search of Medline, PubMed, Cochrane, CINAHL and Google Scholar in January 2021. Reference lists of the chosen sources were reviewed to identify any further relevant sources. We restricted our search to articles published after 2007 as smartphones and mobile apps were rarely available before.

The initial search yielded 2248 potentially relevant citations. Five authors (I.R., M.S., M.R.S., C.S. and D.H.) reviewed titles and abstracts to determine relevance for further review of the full texts in accordance with inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria for the title and abstract screening were the following:

- 1)

- The target groups of the study are ethnic or cultural minorities or migrants,

- 2)

- Digital health tools are used or developed as an intervention,

- 3)

- The intervention targets specific or general health issues (including wellbeing and health literacy).

All three aspects needed to be present for a publication to be included. Publications that did not contain all three criteria were excluded.

2.3. Study Selection

To manage the independently reviewed title and abstract screening process, we used Covidence Software (Covidence Systematic Review Software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, VI, Australia). We imported 2248 studies into Covidence, where duplicates were automatically signaled and removed based on an exact match of the title, date and author (608 duplicates). Two reviewers independently reviewed each title and abstract and conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer.

To ensure a common understanding of the inclusion criteria, reviewers met several times and discussed “conflict” cases, where the ratings of studies did not match. After the end of the title and abstract screening, a second round of title and abstract screening was done, sending all papers back into screening, as we felt that our understanding of the research question and inclusion criteria had become clearer and more aligned. The PRISMA diagram below reflects this second round of title and abstract screening, where 1456 studies were ultimately excluded (see Figure 1).

We then included 184 studies in the full-text screening. During this stage, two reviewers read the full text versions of the papers and a third reviewer decided in case of conflict. Additionally to the already defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (see above), several exclusion criteria were added (see Figure 1). Thus, studies were excluded if they were general articles on the digital health literacy of migrant populations, which did not define or test digital interventions (35), if they were not sufficiently focused on ethnic minorities or migrants (17), if they were research protocols without outcomes where digital interventions are presented without delving into use and viability (16), if they did not include digital interventions (12) or if they were not health interventions (5). Furthermore, several papers were excluded for formal reasons: because we had no access to the full text version (15) or because they were PhD or master theses (9), reviews (systematic, scoping, narrative, etc.) (7), entire books (3), methodological (4) or conference papers (1). Lastly, we excluded papers that were earlier versions of studies we included in our scoping review (3).

Before extraction we proceeded with the reference screening of the studies. A manual search of the reference lists of all included articles (title and abstract, then full text screening by the three main authors) resulted in an additional three studies which were included in the review.

3. Results

A total of 57 publications that met all inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the final review.

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. We charted the studies according to region/country of provenance, study design, number of participants, target population, technology, area of intervention, health/wellbeing problem and degree of participation of target groups.

3.2. Region

Among the 57 studies included in our final selection, 37 (65%) were from the USA, nine were from countries of the European Union (16%), four (7%) were from Australia/Oceania, two (4%) were from Asia, two (4%) were from Canada, one (2%) was from the UK and one (2%) was from Africa. One (2%) study was a collaboration between Germany, Sweden and Egypt and another (2%) was a collaboration between Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Liechtenstein.

3.3. Study Design and Number of Participants

A total of 19 studies (33%) were randomized controlled trials (RCT), 15 studies (26%) used qualitative methods and seven (12%) used mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative methods). Two studies (4%) were non-randomized studies and four (7%) were cohort studies. Two (4%) were feasibility and acceptability studies and two (4%) were cross-sectional studies. Two (4%) were single-group pre- and post-test studies, one (2%) was a feasibility and acceptability study, one (2%) was an experimental study and one (2%) was an intervention study. The number of participants ranged from 9 [43] to 1512 [48].

3.4. Target Population

Among our studies, 46 out of 57 (81%) focused on migrants or ethnic minorities as the target population, while seven (12%) focused on refugees or displaced persons. Four studies (7%) focused on a combination of migrants, ethnic minorities and refugees, ethnic minorities and sexual minorities, as well as low-income individuals and migrants and ethnic minorities.

3.5. Digital Technology

Seven different types of digital technologies were identified that were used or developed in the studies: 20 mHealth/Apps (35%), 13 websites and/or informational videos (22%), 8 studies (14%) using text messages, 8 studies (14%) using other telehealth-technologies and 4 studies (7%) using technologies from a combination of websites, email, apps and text messages. Two studies (4%) focused on social media and a further two studies (4%) used other technologies such as interactive assessments and YouTube.

3.6. Intended Use of the Digital Tools

We found that the digital tools developed, tested or evaluated in the publications were aimed at the following eight areas of health intervention (as declared in the respective publications) in decreasing order of representation in our sample:

- -

- Providing health information to a population afflicted by a particular illness or condition (22 studies, 39%).

- -

- Self-management of illness, for instance, through the rating and tracking of symptoms and medication (14 studies, 25%).

- -

- Prevention of illness (e.g., diabetes, weight gain) (seven studies, 12%).

- -

- Facilitating consultations with health professionals either through reminders for appointments or through e-consultations (six studies, 10%).

- -

- Facilitating patient support groups or patient networking (three studies, 5%).

- -

- Hybrid forms of intervention, comprising of two or more of these dimensions (three studies, 5%).

- -

- Language translation, usually during consultations (one study, 2%).

- -

- Home monitoring system to track movement (one study, 2%).

3.7. Health Focus

The selected studies addressed various health and wellbeing topics and risks and illnesses in decreasing order: mental health/wellbeing (14 studies, 25%), pregnancy and/or postpartum (eight studies, 14%), overall health–lifestyle-habits (eight studies, 14%), HIV and/or other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) (eight studies, 14%), diabetes (five studies, 9%), infectious diseases (four studies, 7%), cancer (four studies, 7%), obesity (three studies, 5%), neurological conditions (two studies, 3%) and cardiac diseases (one study, 2%).

3.8. Degree of Participation of Target Groups in DHI Development

Our most important unit of analysis was the degree of participation of the target groups. Some studies did not ask the target groups for any feedback or involve them in any way in the development of the interventions, while others involved these stakeholders in every step of the process.

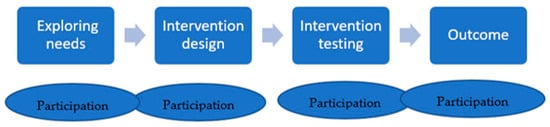

Based on the participation of the target groups during the development of the DHIs described in our studies, we outlined four phases of DHI development inductively (see Figure 1) and developed a typology of our studies according to the degree of user involvement and the timing of participation (Figure 2).

We identified four types of studies:

- Type 1: Participation at the outcome stage of intervention;

- Type 2: Participation before intervention design;

- Type 3: Participation in intervention testing;

- Type 4: Participation throughout the development process.

3.8.1. Type 1: Participation at the Outcome Stage of Intervention

Among the selected studies, 33 out of 57 (55%) can be categorized as type 1, with the least amount of participation of the target groups in any phase of development of the digital health intervention. These studies usually investigate the effectiveness of the interventions in terms of outcomes. It is at this final stage that participants are asked to provide feedback on efficacy, acceptability or usability. The acceptability, feasibility and usability of the intervention are often evaluated through a secondary data analysis (e.g., length of use of the DHIs). Sometimes acceptability is analyzed through short questionnaires (yes/no answers or open answers) about the usefulness of the intervention [36]. Rarely, more in-depth feedback is provided in qualitative interviews [43] or focus groups [48]. This feedback is not considered for an adaptation of the interventions, though it is not excluded that this might be done in the future. Most of the studies in this category are RCTs with a minority of qualitative or mixed-method studies. The most frequently used digital interventions were apps, websites, text messaging and telemedicine. Many of these studies address the health issue of mental health and well-being, as well as overall lifestyle issues.

Often these are digital interventions that have been developed for the general population, that are now being used for more ethnic and culturally diverse populations with few or no adaptations.

Some studies show a short-term improvement of illness symptoms such as depression or other mental health issues [26,42,52], diabetes [27], a better knowledge of health information [20,30,44], increased mammogram take-up [32] and an increase in positive health behaviors, such as vaccination [29,31]. Some of these DHIs show a good acceptance among the target population [23,26,35,36,39]. However, not all interventions are successful, with some studies reporting participant resistance to digital solutions and a preference for in-person care [22,40,45], a tendency to worsen the exclusion of less tech-affine individuals [37], no positive effects [46] or a drop in positive effects of the DHIs once more time has passed and adherence has dropped [25].

Lee et al. [32] showed that digital interventions can reach underserved and hard-to-recruit populations that bear disproportionate cancer burdens. The study by Borsari [23] showed a high acceptance towards the Pregnancy and Newborn Diagnostic System (PANDA) for antenatal care for a multiethnic and mobile population. Studies in which text messages are used seem to be effective and help improve health and wellbeing outcomes. For example, messages improved women’s mood, helped them feel more connected with their social environment [26], engaged patients in their health and increased the rate of influenza vaccinations [29,31]. Röhr et al. [40] were further able to show a high usability of the Sanadak digital intervention (SUS-usability score of 78.9 within a range of 0 to 100). It aimed at reducing mild-to-moderate post-traumatic stress in Syrian refugees. However, this intervention was not more effective than the control condition and not more cost-effective. Therefore, the authors found that Sanadak is not suitable as a stand-alone treatment.

3.8.2. Type 2: Participation before Design

Type 2 is characterized by exploring the needs of the target population before developing the intervention. This is done to better tailor the intervention to the specific needs of the target group. Eight studies (12%) can be classified as this type. Four of the eight studies developed a digital intervention: An SMS program of information for pregnant African American and African Caribbean immigrant women in New York City [53], a personal digital assistant program to promote fruit and vegetable intake to low-income, ethnic minority girls [57], websites, including YouTube, about HIV/STDs for ethnic, racial, sexual minority 15–24-year-old adolescents [60] and a culturally sensitive technology-based campaign focused on HIV testing [60]. One study used a Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) of the need to adapt interventions: e.g., a telehealth service for Colorado Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) was adapted for young adults from racial/ethnic minorities and low socioeconomic backgrounds with T1D [58]. Another study used text messages to provide diabetic retinopathy awareness and improve diabetic-eye-care behavior for indigenous women with or at risk of diabetes [59]. One study examined the use of a digital intervention, text messages called mMom, to improve access to maternal, newborn and child health service for ethnic minority women in Vietnam [56] and one study explored health education videos for acceptability by Somali refugee women [54].

To engage the target population and understand participants’ perceptions of the use and needs before developing the intervention, four of seven studies used a mixed method approach. Blackwell et al. [53] conducted focus groups and used key informants, interviews and observations. The resulting qualitative themes were used to develop a survey instrument. Nollen et al. [57] employed focus groups and a Health Technology Questionnaire. Raymond et al. [58] employed a patient advisory board, stakeholder focus groups and a survey. Umaefulam et al. [59] utilized Sharing Circles and a survey.

Five studies used a participatory approach to investigate the needs of the target groups: McBride et al. [56] used various participatory methods including focus groups [54], ethnography and interviews and Whitley et al. [60] used focus groups. Raymond et al. [58] involved Patient Advisory Council members in the project to discuss their experiences, preferences and priorities for telehealth care for diabetic patients and their interest in participating in group appointments. Umaefulam et al. [59] used Sharing Circles to gain an inside perspective from indigenous women involved in the intervention to increase the cultural sensitivity in the developing content for the intervention.

Nollen et al. [57] were able to show that the iterative involvement of young people in all phases of the development of the wearable computer program was successful in creating changes in participants’ health behaviors. Umaefulam et al. [59] were able to show that mHealth education increased awareness and resulted in a change in diabetic-eye-care behaviors.

3.8.3. Type 3: Participation in Intervention Testing

Type 3 is characterized by the involvement of the target group during the testing phase and an adaptation of the intervention. Nine of the fifty-seven studies (17%) can be classified as this type. In five of the ten studies, the specific needs of the target group were first identified. Then, the DHIs were adapted according to these needs.

As in type two, the involvement of the target group in type three was carried out using qualitative methods in most of the included studies. Seven of the ten studies used qualitative methods: Handley et al. [63] and Lee et al. [32] conducted focus groups, Burchert et al. [61], Liss et al. [65] and Quarells et al. [67] conducted both focus groups and interviews and Zheng and Woo [52] assembled the participants for a talking-based workshop. The other three studies used quantitative methods: Muroff et al. [66] used the collected data from an app, Tanner et al. [69] carried out a survey and Liss et al. [65] and Dorfman et al. [63] used mixed-method approaches. In terms of digital tools, three studies used telehealth technologies, four used apps, one used videos, one used text messages, one used social media and one used YouTube videos.

The studies identified several advantages of using digital technologies. Dorfman et al. [62] and Lee et al. [64] were able to show an improved accessibility of underserved patient populations when technologies were adapted. The study of Dorfman et al. [62] suggests that appropriately adapted mobile-health technologies may provide an avenue to reach underserved patients and implement behavioral interventions to improve pain management. The study of Lee et al. [64] demonstrated how culturally relevant information can be collected to develop a text message intervention to incorporate the perspective of the target population at the intervention development stage. The study findings may help in the development of future interventions targeting different types of cancer screening in other underserved racial or ethnic groups.

Muroff et al. [66] and Quarells et al. [67] were able to show that digital interventions have the potential to expand access to culturally and linguistically competent services. In addition, Quarells et al. [67] adapted their project UPLIFT, a digital health intervention for the self-management of depression to Black and Hispanic people with epilepsy, through a careful and systematic adaptation process to new populations or cultural settings. This shows that digital interventions can expand the available strategies of a health problem while needing to be carefully and systematically adapted to the new population or cultural setting.

3.8.4. Type 4: Participation throughout Development Process

Type 4 represents the kind of studies that take the tailoring of the digital intervention to the target group in question one step further. A digital intervention is thus not merely adapted to a new group of participants, but the intervention is developed from its inception according to the needs of the group and with their participation at several stages of development and/or implementation. It is the most participative type of DHI and the closest to a co-design process [70,74,75]. Only seven of our studies correspond to this type with the highest degree of participation (12%). Most studies in this category are qualitative studies, using qualitative interviews, focus groups and mixed methods. One study [72] is an RCT and one [70] combines a RCT and a focus group.

These studies report a high level of success in changing health behaviors, improving health knowledge, lowering barriers, as well as improving acceptability, usability and satisfaction. They focus on understanding the needs of the target group before developing the digital technology. To comprehend the participants’ needs, the studies used mainly qualitative methods, such as focus groups, to understand women’s views of breast cancer, attitudes toward mammography and preferred content, or meetings with community health leaders involved in cancer care and women’s health [76]. The focus groups found that a community-based, participatory social marketing approach can be used successfully to create more culturally appropriate text messages in order to lower barriers for HIV testing [73].

Wang et al. [76] concluded that integrating dermatology care through a telemedicine system can lead to improved access for underserved patients. The results show that tele-dermatology is increasing in adoption for diverse patient populations. This is evidenced by the higher number of underserved and underinsured groups that were reached with tele-dermatology compared to conventional referrals, providing a much-needed service to a more diverse patient population. In addition, fewer appointments were missed and users were able to see a dermatologist in person and receive skin cancer treatment more quickly compared to conventional referrals. Brewer et al. [70] developed a culturally relevant cardiovascular health and wellness mobile health tool using a community-based participatory approach. The result was that culturally relevant lifestyle interventions could be implemented and delivered by mobile health tools.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

This scoping review aimed to analyze which digital health tools are available for migrant and cultural or ethnic minority populations, as well as what role their participation plays in the development and successful uptake of DHIs. Since new technologies such as apps or smartphones have only been available since ca. 2007, studies focusing on DHIs developed for immigrant, ethnic and cultural minorities are also relatively new.

Our study highlights the importance of the use of participatory methods in the development of DHIs for migrant and cultural or ethnic minority populations. We identified four types of DHIs describing different degrees of target group participation in the development of digital intervention, with Type 1 representing the lowest level of participation and Type 4 the highest. We did not use existing models of digital health intervention development. Instead, we inductively analyzed the stages of development as well as the degree of participation of the target groups, as described in the studies we included in our review.

Overall, there seems to be a larger focus on developing DHIs for ethnic or cultural minorities and migrants in the USA (e.g., Latino or Black communities), where 65% of our 57 studies were from, and less on minority and migrant communities in Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia. While findings from different regions can be transferred, addressing this unequal distribution in the future is important as population diversity and heterogeneity are global phenomena. Furthermore, the studies we reviewed focused mostly on migrants and cultural or ethnic minorities and less on refugees, showing a general tendency to prioritize the development of DHIs for people with a settled legal status over those with a precarious or unclear immigration status.

In terms of methodology, we found that the most common types of studies were RCTs (34%) followed by qualitative studies (30%). This is an interesting development as qualitative or mixed-method studies especially allow the use of participatory methods, showing a growing concern for this topic. The most widely used technologies were mhealth interventions (35%), followed by websites and informational videos (23%), text messages (14%) and telehealth (14%). Indeed, many of the studies we reviewed highlighted the increasing importance of mobile phones in providing low-threshold health interventions for marginalized populations, as well as for the delivery of tailored health information in order to motivate, provide support and empower individuals.

Among the studies we reviewed, most were aimed at illness self-management, followed by consultations and prevention. The main health issues the DHIs addressed were mental health and wellbeing (23%), followed by pregnancy and postpartum (17%) and overall lifestyle habits (15%), which correspond to some of the leading health challenges that migrant and minority populations are faced with over time in host countries [77,78].

Most of the studies we found (53%, N = 28) are type 1, meaning that their digital intervention is evaluated in terms of acceptability with the target population, feasibility or effectiveness after it has been developed. There is typically no feedback loop allowing for an adaptation of the digital interventions according to the findings of the studies or feedback from the target group. Type 2 (11% of studies) includes a higher degree of participation than type 1, as the needs of the target population are identified before developing the intervention. Type 3 are studies where the target group participated during the testing phase of the digital intervention as well as in the adaptation of the intervention according to the community needs. This was the second most common type of study (23%). Type 4 (11%) represented the most inclusive studies where the target group was involved in every step of development and evaluation from analyzing their needs to the development, testing and use of the intervention.

Studies classified as type 2, 3 and 4 used more qualitative methods than studies in type 1. Our review indicates that focus groups, interviews and mixed-method approaches are particularly suited for a community health approach to DHI development.

Overall, the studies in our review show the importance of language in the development of DHIs in order to reduce barriers to the uptake and use of digital health tools [79]. Thus many of the analyzed DHIs included health information not just in the national language, but also in the native languages of target populations. Some went a step further and culturally tailored the messaging to the communities in question. This type of tailored development seems to increase the ability to reach particularly underserved groups, yet it also requires a higher degree of target population involvement and co-design. This echoes findings from other studies such as Gonzalez et al. [80], which showed that participatory design and co-design can benefit long-term engagement with mHealth tools, and Jang et al. [81], who showed how participation can improve access and enrollment in digital interventions. However, as analyzed by Evans et al. [82], in future work, the definitions of participatory design or co-design need to continue to be scrutinized in order to better understand and improve the impact of these design practices on equity in health.

4.2. Limitations

One of the limitations of our study lies in the definition of migration and ethnic or cultural minorities that we used for our search. This concept includes populations who are White as well as People of Color, migrants as well as refugees, and we found them to be some of the most widely used concepts in health research internationally. We did not, however, include similar concepts such as “other” or “othering” that are more widely used in social sciences and migrations research. This could have potentially yielded further search results. Similar to Gonzales [80], we considered the effectiveness of the digital interventions at the individual level based on the authors’ self-reports. Additionally, though we presented the impact DHIs had on health and wellbeing outcomes as well as long-term usability and adherence to treatment or lifestyle changes, our insights are limited by the time horizon of the studies. In the future, an updated scoping review or other systematic reviews should be conducted to measure the long-term impact of participatory approaches. It may also be that studies were conducted at various stages of technology development or follow-up studies were conducted but not published. Furthermore, we must be aware that negative or not suitable results are usually not published. The authors of the study have different disciplinary backgrounds, including nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and sociology. In this way, they bring in different perspectives that may have led to different ratings of the studies. As with all other interventions, it is an open question whether these effects last in the long term.

5. Conclusions

The previous literature has pointed out the importance of participatory and user-centered development of digital health interventions and the circular involvement of end users, especially to reach communities that face particularly high barriers to healthcare [80]. Migrants, refugees and cultural or ethnic minorities are among these particularly vulnerable groups. In our scoping review, we focused on the digital health interventions aimed specifically at these groups and analyzed their self-reported effectiveness, as well as the degree of participation of their target group, in the development or implementation of the intervention. We found that despite the high health needs of this population, among 2248 studies, only 57 targeted migrants, refugees or cultural or ethnic minorities in particular. Of these 57 studies, about half applied the digital health technology developed for the general population to the migrant or minority populations without making any adaptations to their specific cultural, linguistic or health needs. The other half assessed their needs, adapted the digital interventions accordingly and/or involved the target population in development and/or testing. Only a small fraction of the studies included in this review reported a high level of participation of migrant and cultural or ethnic minority populations in the design of the digital health tools. This indicates that such practices continue to be the exception rather than the norm in DHI development. Findings from these studies, however, seem to indicate that increased participation has the potential to improve health outcomes, acceptance and use of DHIs in migrant and minority populations.

Author Contributions

Project administration: I.R. and J.P.-M.; Conceptualization: I.R., M.S., M.R.S., C.S., D.H.-S. and J.P.-M.; Methodology: I.R., M.S., M.R.S., C.S., D.H.-S. and J.P.-M.; Systematic search and screening: I.R., M.S., M.R.S., C.S. and D.H.-S.; Extraction: I.R., M.S. and M.R.S.; Writing the first draft: I.R. and M.S.; Editing the first draft: I.R., M.S., M.R.S. and J.P.-M.; Further editing and finalization: I.R. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded with the support of the ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, School of Health Sciences, and the ZHAW Research Focus “Social Integration”. Open access and APC funding was provided by ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable as this study is a review and doesn’t involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Keywords used for the systematic search process in this scoping review can be found under https://osf.io/dnp2j/ (accessed on 1 July 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lupton, D. The digitally engaged patient: Self-monitoring and self-care in the digital health era. Soc. Theory Health 2013, 11, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. Beyond Techno-Utopia: Critical Approaches to Digital Health Technologies. Societies 2014, 4, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F.; Newman, L.; Biedrzycki, K. Vicious Cycles: Digital Technologies and Determinants of Health in Australia. Health Promot. Int. 2012, 29, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, J.; Koola, J.; Contreras, A.; Castillo, A.K.; Ruiz, M.; Tedone, K.G.; Yakuta, M.; Schiaffino, M.K. Consumer Health Informatics Adoption among Underserved Populations: Thinking beyond the Digital Divide. Yearb. Med. Inf. 2018, 27, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández Da Silva, Á.; Buceta, B.B.; Mahou-Lago, X.M. eHealth Policy in Spain: A Comparative Study between General Population and Groups at Risk of Social Exclusion in Spain. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221120724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson-Lewis, C.; Darville, G.; Mercado, R.E.; Howell, S.; Di Maggio, S. mHealth Technology Use and Implications in Histori-cally Underserved and Minority Populations in the United States: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, R.; Sewell, A.A.; Gilbert, K.L.; Roberts, J.D. Missed Opportunity? Leveraging Mobile Technology to Reduce Racial Health Disparities. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 2017, 42, 901–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, L.; Buresh, M.; Rios, N.; Conley, A.; Flys, T.; Page, K.R. Cell Phone Utilization among Foreign-Born Latinos: A Promising Tool for Dissemination of Health and HIV Information. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2014, 16, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, L.C.; Hayes, S.N.; Caron, A.R.; Derby, D.A.; Breutzman, N.S.; Wicks, A.; Raman, J.; Smith, C.M.; Schaepe, K.S.; Sheets, R.E.; et al. Promoting Cardiovascular Health and Wellness among African-Americans: Community Participatory Approach to Design an Innovative Mobile-Health Intervention. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisnell, D.; Rubin, J.; Spool, J. Handbook of Usability Testing: Howto Plan, Design, and Conduct Effective Tests; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-08040-5. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen, J.; Robertson, T. (Eds.) Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-415-69440-7. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Classification of Digital Health Interventions v1.0: A Shared Language to Describe the Uses of Digital Technology for Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Soobiah, C.; Cooper, M.; Kishimoto, V.; Bhatia, R.S.; Scott, T.; Maloney, S.; Larsen, D.; Wijeysundera, H.C.; Zelmer, J.; Gray, C.S.; et al. Identifying Optimal Frameworks to Implement or Evaluate Digital Health Interventions: A Scoping Review Protocol. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, D.W.L.; Li, L.; Daoust, G.D. Factors Influencing Suicide Behaviours in Immigrant and Ethno-Cultural Minority Groups: A Systematic Review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2017, 19, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OHCHR. Concept of a Minority: Mandate Definition. In Special Rapporteur on Minority Issues; OHCHR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- GOV.UK, UK Government. Writing about Ethnicity. Available online: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/style-guide/writing-about-ethnicity (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Society Foundation (OSF). Digital Health for Parents with Migration Experience—A Scoping Review. 2021. Available online: https://osf.io/dnp2j/ (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Abu-Saad, K.; Murad, H.; Barid, R.; Olmer, L.; Ziv, A.; Younis-Zeidan, N.; Kaufman-Shriqui, V.; Gillon-Keren, M.; Rigler, S.; Berchenko, Y.; et al. Development and Efficacy of an Electronic, Culturally Adapted Lifestyle Counseling Tool for Improving Diabetes-Related Dietary Knowledge: Randomized Controlled Trial Among Ethnic Minority Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, M.S.; Cooper, B.A.; Park, L.G.; Padash, S.; Arai, S. A Feasible and Efficacious Mobile-Phone Based Lifestyle Intervention for Filipino Americans with Type 2 Diabetes: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Diabetes 2017, 2, e8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, C.; Chan, K.T.; Choi, Y. Sensor-Based Passive Remote Monitoring and Discordant Values: Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Low-Income Immigrant Elders in the United States. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e11516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsari, L.; Stancanelli, G.; Guarenti, L.; Grandi, T.; Leotta, S.; Barcellini, L.; Borella, P.; Benski, A.C. An Innovative Mobile Health System to Improve and Standardize Antenatal Care Among Underserved Communities: A Feasibility Study in an Italian Hosting Center for Asylum Seekers. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, T.; Marziali, E.; Colantonio, A.; Carswell, A.; Gruneir, M.; Tang, M.; Eysenbach, G. Internet-Based Caregiver Support for Chinese Canadians Taking Care of a Family Member with Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementia. Can. J. Aging Rev. Can. Vieil. 2009, 28, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comulada, W.S.; Swendeman, D.; Koussa, M.K.; Mindry, D.; Medich, M.; Estrin, D.; Mercer, N.; Ramanathan, N. Adherence to Self-Monitoring Healthy Lifestyle Behaviours through Mobile Phone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessments and Photographic Food Records over 6 Months in Mostly Ethnic Minority Mothers. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Y.; Ferrás, C.; Rocha, Á.; Aguilera, A. Exploratory Study of Psychosocial Therapies with Text Messages to Mobile Phones in Groups of Vulnerable Immigrant Women. J. Med. Syst. 2019, 43, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Islam, N.; Trinh-Shevrin, C.; Wu, B.; Feldman, N.; Tamura, K.; Jiang, N.; Lim, S.; Wang, C.; Bubu, O.M.; et al. A Social Media-Based Diabetes Intervention for Low-Income Mandarin-Speaking Chinese Immigrants in the United States: Feasibility Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e37737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, H.; Christensen, U.; Juhl, M.; Villadsen, S.F. Implementing the MAMAACT intervention in Danish antenatal care: A qualitative study of non-Western immigrant women’s and midwives’ attitudes and experiences. Midwifery 2021, 95, 102935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharbanda, E.O. Effect of a Text Messaging Intervention on Influenza Vaccination in an Urban, Low-Income Pediatric and Adolescent Population: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2012, 307, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiropoulos, L.A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Blashki, G. Effects of a Multilingual Information Website Intervention on the Levels of Depression Literacy and Depression-Related Stigma in Greek-Born and Italian-Born Immigrants Living in Australia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011, 13, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.; Hemmige, V.; Kallen, M.A.; Street, R.L.J.; Giordano, T.P.; Arya, M. The Role of Text Messages in Patient-Physician Communication about the Influenza Vaccine. J. Mob. Technol. Med. 2018, 7, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lee, H.Y.; Lee, M.H.; Gao, Z.; Sadak, K. Development and Evaluation of Culturally and Linguistically Tailored Mobile App to Promote Breast Cancer Screening. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linke, S.E.; Dunsiger, S.I.; Gans, K.M.; Hartman, S.J.; Pekmezi, D.; Larsen, B.A.; Mendoza-Vasconez, A.S.; Marcus, B.H. Between Physical Activity Intervention Website Use and Physical Activity Levels Among Spanish-Speaking Latinas: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Yin, Z.; Lesser, J.; Li, C.; Choi, B.Y.; Parra-Medina, D.; Flores, B.; Dennis, B.; Wang, J. Community Health Worker-Led mHealth-Enabled Diabetes Self-management Education and Support Intervention in Rural Latino Adults: Single-Arm Feasibility Trial. JMIR Diabetes 2022, 7, e37534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Jiang, T.; Yu, K.; Wu, S.; Jordan-Marsh, M.; Chi, I. Care Me Too, a Mobile App for Engaging Chinese Immigrant Caregivers in Self-Care: Qualitative Usability Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2020, 4, e20325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, F.; Chandra, S.; Furaijat, G.; Kruse, S.; Waligorski, A.; Simmenroth, A.; Kleinert, E. A Digital Communication Assistance Tool (DCAT) toObtain Medical History from Foreign-LanguagePatients: Development and Pilot Testing in a PrimaryHealth Care Center for Refugees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L.A.; Mulvaney, S.A.; Gebretsadik, T.; Ho, Y.-X.; Johnson, K.B.; Osborn, C.Y. Disparities in the Use of a mHealth Medication Adherence Promotion Intervention for Low-Income Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2016, 23, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nollen, N.L.; Mayo, M.S.; Carlson, S.E.; Rapoff, M.A.; Goggin, K.J.; Ellerbeck, E.F. Mobile technology for obesity prevention: A randomized pilot study in racial- and ethnic-minority girls. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrino, T.; Estrada, Y.; Huang, S.; St. George, S.; Pantin, H.; Cano, M.Á.; Lee, T.K.; Prado, G. Predictors of Participation in an eHealth, Family-Based Preventive Intervention for Hispanic Youth. Prev. Sci. 2018, 19, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röhr, S.; Jung, F.U.; Pabst, A.; Grochtdreis, T.; Dams, J.; Nagl, M.; Renner, A.; Hoffmann, R.; König, H.-H.; Kersting, A.; et al. A Self-Help App for Syrian Refugees with Posttraumatic Stress (Sanadak): Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e24807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, T.R.; Richards, M.; Gasko, H.; Lohrey, J.; Hibbert, M.E.; Biggs, B.-A. Telehealth: Experience of the first 120 consultations delivered from a new Refugee Telehealth clinic: Telehealth: Still a long way to go. Intern. Med. J. 2014, 44, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanhel, K.; Hovestadt, E.; Lehr, D.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Baumeister, H.; Bengel, J.; Sander, L.B. Engaging Refugees with a Culturally Adapted Digital Intervention to Improve Sleep: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 832196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, A.E.; Mann-Jackson, L.; Song, E.Y.; Alonzo, J.; Schafer, K.R.; Ware, S.; Horridge, D.N.; Garcia, J.M.; Bell, J.; Hall, E.A.; et al. Supporting Health Among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women With HIV: Lessons Learned From Implementing the weCare Intervention. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 21, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.A.; Joshi, A.; Hernandez, R.G.; Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Arora, M.; Luna, R.; Ellen, J.M. Nutrition Education via a Touchscreen: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Latino Immigrant Parents of Infants and Toddlers. Acad. Pediatr. 2012, 12, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita, A.; Kandolo, K.M.; Susser, E.; Burns, J.K. Use of Short Messaging Services to Assess Depressive Symptoms among Refugees in South Africa: Implications for Social Services Providing Mental Health Care in Resource-Poor Settings. J. Telemed. Telecare 2016, 22, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlü Ince, B.; Cuijpers, P.; van ’t Hof, E.; van Ballegooijen, W.; Christensen, H.; Riper, H. Internet-Based, Culturally Sensitive, Problem-Solving Therapy for Turkish Migrants with Depression: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Veen, Y.J.J.; van Empelen, P.; de Zwart, O.; Visser, H.; Mackenbach, J.P.; Richardus, J.H. Cultural Tailoring to Promote Hepatitis B Screening in Turkish Dutch: A Randomized Control Study. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollersheim, D.; Koh, L.; Walker, R.; Liamputtong, P. Constant Connections: Piloting a Mobile Phone-Based Peer Support Program for Nuer (Southern Sudanese) Women. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2013, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Shim, R.; Lukaszewski, T.; Yun, K.; Kim, S.H.; Rust, G. Telepsychiatry services for Korean immigrants. Telemed. J. E-Health 2012, 18, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, A.; Martinson, M.A.; Baer, L.; Chen, J.; Clain, A.; Williams, A.; Chang, T.E.; Trinh, N.H.T.; Alpert, J.E.; Fava, M. The Effectiveness of Telepsychiatry-Based Culturally Sensitive Collaborative Treatment for Depressed Chinese American Immigrants: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, e996–e1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S.D.; Holloway, I.; Jaganath, D.; Rice, E.; Westmoreland, D.; Coates, T. Project HOPE: Online Social Network Changes in an HIV Prevention Randomized Controlled Trial for African American and Latino Men Who Have Sex with Men. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 1707–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Woo, B.K.P. E-Mental Health in Ethnic Minority: A Comparison of Youtube and Talk-Based Educational Workshops in Dementia. Asian J. Psychiatry 2017, 25, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, T.M.; Dill, L.J.; Hoepner, L.A.; Geer, L.A. Using Text Messaging to Improve Access to Prenatal Health Information in Urban African American and Afro-Caribbean Immigrant Pregnant Women: Mixed Methods Analysis of Text4baby Usage. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e14737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeStephano, C.C.; Flynn, P.M.; Brost, B.C. Somali Prenatal Education Video Use in a United States Obstetric Clinic: A Formative Evaluation of Acceptability. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 81, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Herrera, J.A.; Cardona, J.; Cruz, L.Y.; Munguía, L.; Vera, C.A.L.; Robles, G. Culturally Tailored Social Media Content to Reach Latinx Immigrant Sexual Minority Men for HIV Prevention: Web-Based Feasibility Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e36446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, B.; O’Neil, J.D.; Hue, T.T.; Eni, R.; Nguyen, C.V.; Nguyen, L.T. Improving Health Equity for Ethnic Minority Women in Thai Nguyen, Vietnam: Qualitative Results from an mHealth Intervention Targeting Maternal and Infant Health Service Access. J. Public Health 2018, 40, ii32–ii41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nollen, N.L.; Hutcheson, T.; Carlson, S.; Rapoff, M.; Goggin, K.; Mayfield, C.; Ellerbeck, E. Development and functionality of a handheld computer program to improve fruit and vegetable intake among low-income youth. Health Educ. Res. 2013, 28, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Raymond, J.K.; Reid, M.W.; Fox, S.; Garcia, J.F.; Miller, D.; Bisno, D.; Fogel, J.L.; Krishnan, S.; Pyatak, E.A. Adapting Home Telehealth Group Appointment Model (CoYoT1 Clinic) for a Low SES, Publicly Insured, Minority Young Adult Population with Type 1 Diabetes. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2020, 88, 105896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umaefulam, V.O. Impact of Mobile Health (Mhealth) in Diabetic Retinopathy (Dr) Awareness and Eye Care Behavior among Indigenous Women. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley, L.B.; Brown, L.K.; Curtis, V.; Ryoo, H.J.; Beausoleil, N. Publicly Available Internet Content as a HIV/STI Prevention Intervention for Urban Youth. J. Prim. Prev. 2018, 39, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchert, S.; Alkneme, M.S.; Bird, M.; Carswell, K.; Cuijpers, P.; Hansen, P.; Heim, E.; Harper Shehadeh, M.; Sijbrandij, M.; van’t Hof, E.; et al. User-Centered App Adaptation of a Low-Intensity E-Mental Health Intervention for Syrian Refugees. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfman, C.S.; Kelleher, S.A.; Winger, J.G.; Shelby, R.A.; Thorn, B.E.; Sutton, L.M.; Keefe, F.J.; Gandhi, V.; Manohar, P.; Somers, T.J. Development and Pilot Testing of an mHealth Behavioral Cancer Pain Protocol for Medically Underserved Communities. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2019, 37, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handley, M.A.; Harleman, E.; Gonzalez-Mendez, E.; Stotland, N.E.; Althavale, P.; Fisher, L.; Martinez, D.; Ko, J.; Sausjord, I.; Rios, C. Applying the COM-B Model to Creation of an IT-Enabled Health Coaching and Resource Linkage Program for Low-Income Latina Moms with Recent Gestational Diabetes: The STAR MAMA Program. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.Y.; Lee, M.H.; Sharratt, M.; Lee, S.; Blaes, A. Development of a Mobile Health Intervention to Promote Papanicolaou Tests and Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in an Underserved Immigrant Population: A Culturally Targeted and Individually Tailored Text Messaging Approach. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e13256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liss, D.T.; Brown, T.; Wakeman, J.; Dunn, S.; Cesan, A.; Guzman, A.; Desai, A.; Buchanan, D. Development of a Smartphone App for Regional Care Coordination Among High-Risk, Low-Income Patients. Telemed. E-Health 2020, 26, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muroff, J.; Robinson, W.; Chassler, D.; López, L.M.; Gaitan, E.; Lundgren, L.; Guauque, C.; Dargon-Hart, S.; Stewart, E.; Dejesus, D.; et al. Use of a Smartphone Recovery Tool for Latinos with Co-Occurring Alcohol and Other Drug Disorders and Mental Disorders. J. Dual Diagn. 2017, 13, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quarells, R.C.; Spruill, T.M.; Escoffery, C.; Shallcross, A.; Montesdeoca, J.; Diaz, L.; Payano, L.; Thompson, N.J. Depression Self-Management in People with Epilepsy: Adapting Project UPLIFT for Underserved Populations. Epilepsy Behav. 2019, 99, 106422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungur, H.; Yılmaz, N.G.; Chan, B.M.C.; van den Muijsenbergh, M.E.; van Weert, J.C.; Schouten, B.C. Development and Evaluation of a Digital Intervention for Fulfilling the Needs of Older Migrant Patients with Cancer: User-Centered Design Approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, A.E.; Song, E.Y.; Mann-Jackson, L.; Alonzo, J.; Schafer, K.; Ware, S.; Garcia, J.M.; Arellano Hall, E.; Bell, J.C.; Van Dam, C.N.; et al. Preliminary Impact of the weCare Social Media Intervention to Support Health for Young Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2018, 32, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, L.C.; Jenkins, S.; Hayes, S.N.; Kumbamu, A.; Jones, C.; Burke, L.E.; Cooper, L.A.; Patten, C.A. Community-Based, Cluster-Randomized Pilot Trial of a Cardiovascular mHealth Intervention: Rationale, Design, and Baseline Findings of the FAITH! Trial. Am. Heart J. 2022, 247, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, A.F.; Davis, A.L.; Krishnamurti, T. Adapting a Pregnancy App to Address Disparities in Healthcare Access Among an Emerging Latino Community: Qualitative Study using Implementation Science Frameworks. 2022. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-1555131/v1 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- DeCamp, L.R.; Godage, S.K.; Araujo, D.V.; Cortez, J.D.; Wu, L.; Psoter, K.J.; Quintanilla, K.; Rodríguez, T.R.; Polk, S. A Texting Intervention in Latino Families to Reduce ED Use: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e2019140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.S.; Berkman, N.; Brown, C.; Gaynes, B.; Weber, R.P. Disparities Within Serious Mental Illness; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ospina-Pinillos, L.; Davenport, T.; Mendoza Diaz, A.; Navarro-Mancilla, A.; Scott, E.M.; Hickie, I.B. Using Participatory Design Methodologies to Co-Design and Culturally Adapt the Spanish Version of the Mental Health eClinic: Qualitative Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samkange-Zeeb, F.; Ernst, S.; Klein-Ellinghaus, F.; Brand, T.; Reeske-Behrens, A.; Plumbaum, T.; Zeeb, H. Assessing the Acceptability and Usability of an Internet-Based Intelligent Health Assistant Developed for Use among Turkish Migrants: Results of a Study Conducted in Bremen, Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 15339–15351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.H.; Liang, W.; Schwartz, M.D.; Lee, M.M.; Kreling, B.; Mandelblatt, J.S. Development and Evaluation of a Culturally Tailored Educational Video: Changing Breast Cancer-Related Behaviors in Chinese Women. Health Educ. Behav. 2008, 35, 806–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maio, F.G. Immigration as Pathogenic: A Systematic Review of the Health of Immigrants to Canada. Int. J. Equity Health 2010, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constant, A.F.; García-Muñoz, T.; Neuman, S.; Neuman, T. A “Healthy Immigrant Effect” or a “Sick Immigrant Effect”? Selection and Policies Matter. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2018, 19, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, W.; Amuta, A.O.; Jeon, K.C. Health Information Seeking in the Digital Age: An Analysis of Health Information Seeking Behavior among US Adults. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2017, 3, 1302785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.; Early, J.; Gordon-Dseagu, V.; Mata, T.; Nieto, C. Promoting Culturally Tailored mHealth: A Scoping Review of Mobile Health Interventions in Latinx Communities. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2021, 23, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.; Yoon, J.; Park, N.S. Source of Health Information and Unmet Healthcare Needs in Asian Americans. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, L.; Evans, J.; Pagliari, C.; Källander, K. Exploring the Equity Impact of Current Digital Health Design Practices: Protocol for a Scoping Review. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e34013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).