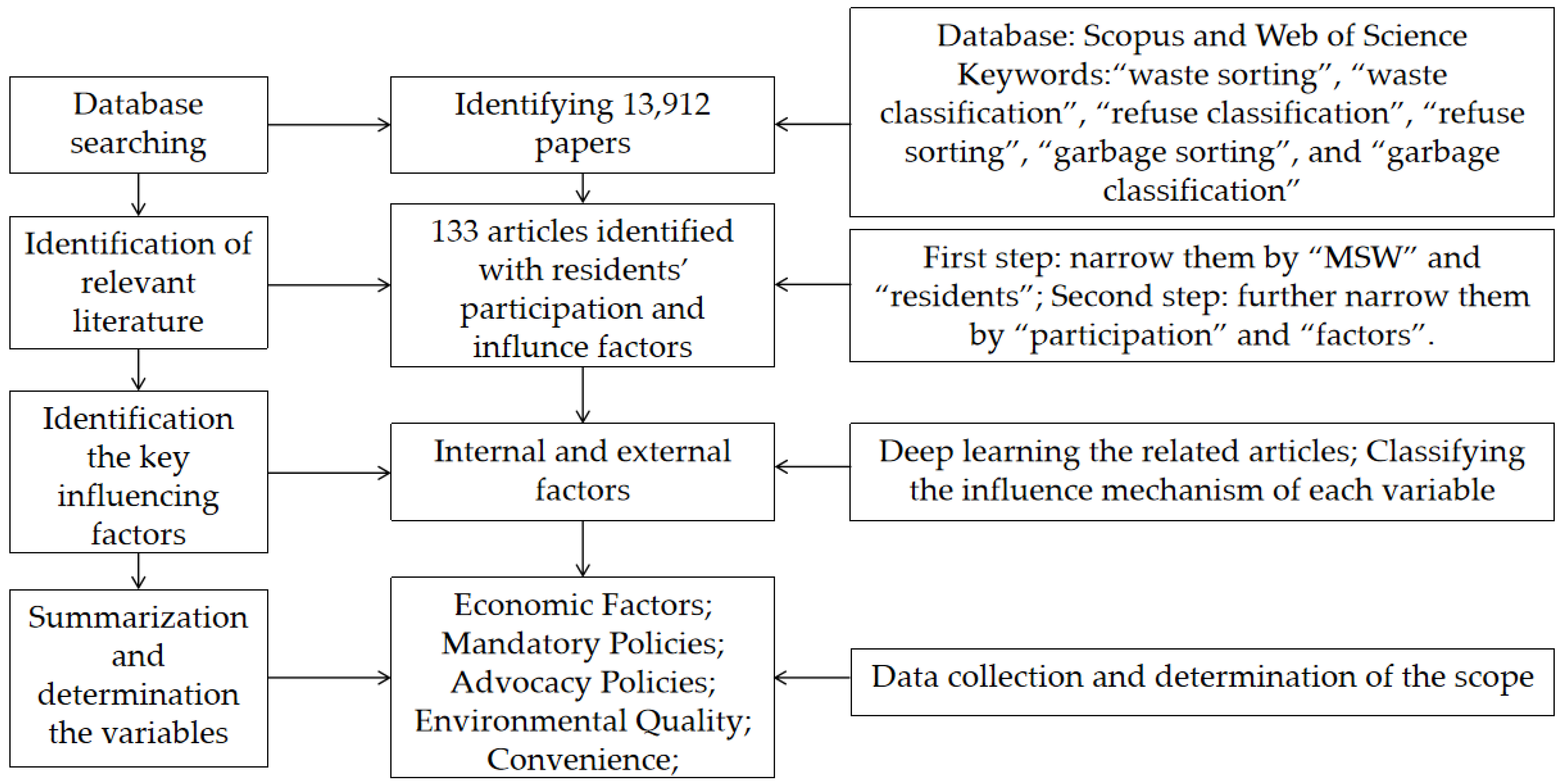

1. Introduction

Rapid industrialization and urbanization have not only led to economic growth and development, but they have also introduced many social and environmental problems, including growing amounts of municipal solid waste (MSW). In 2021, China produced approximately 248 million tons of MSW, which is 1.5 times the amount that was produced in 2004 (155 million tons); by 2030, 480 million tons of MSW are expected to be produced [

1]. During the 13th Five-Year Plan period, the annual growth rate of domestic waste in China is expected to be 6%, and two-thirds of the Chinese cities that are experiencing rapid economic development are expecting to face the problem of “waste siege” [

2]. Sorting waste from the source is considered to be an effective measure that can solve this problem; however, residents’ participation plays a significant role in this process.

MSW disposal generates significant greenhouse gas emissions (GHG); furthermore, it may be considered a waste of resources. In China, after the “Implementation Plan for Domestic Garbage Classification Systems” was introduced in 2017, MSW was divided into the following categories: wet waste (food waste), recyclable waste, hazardous waste, and remaining waste (dry waste). In accordance with the treatment strategy detailed in the plan, kitchen waste is treated using anaerobic digestion or composting methods; recyclable waste is treated using methods that will transform it into usable resources; and the remaining waste will be disposed of via incineration [

3]. To promote sustainable urban development further, waste-to-energy (WtE) treatments, such as waste-to-liquid, waste-to-solid, and waste-to-gas fuels, are needed [

4]; however, unsorted waste is slowing down the development of these treatments. Compared with other countries, China’s kitchen waste comprises a higher level of unclassified and water-rich substances [

5]. The low calorific value and high moisture content of waste restricts its successful transformation into effective resources. China, which has set a goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2060, is under a great deal of pressure to reduce emissions; ensuring that waste is classified when it is generated will be an effective measure that can help reduce GHG.

Even though developed countries have provided us with a framework that demonstrates how to sort MSW, the act of consciously sorting waste is not habitual for most residents. Ensuring that recycling occurs in developing countries still relies on the use of mandatory policies [

6]. Concerning waste management, China began to issue regulations in the 1990s. At the time, due to the enforcement of different regulations across the country, and a lack of infrastructure in certain regions, sorting waste did not gain much popularity [

7]. In June 2016, the first plan for a compulsory waste classification system was implemented. In June 2019, a new regulation was implemented, which established waste classification and treatment systems in 46 pilot cities above the prefecture-level. As a result, Shanghai, a pioneering city in terms of its response to the new directive, witnessed a rapid increase in the sorting rate [

8]. Other pilot cities have gradually introduced local regulations; however, there are still difficulties regarding residents’ participation behavior.

At present, pilot cities are focusing more on the back-end processing of MSW, rather than concentrating on reducing consumption and recycling, which ought to be the main goal of a developing circular economy. In accordance with previous research, more than 50 percent of people in China are willing to support the government’s recycling program; however, waste sorting remains inefficient due to a lack of information on waste classification [

9]. Another reason for residents’ non-participation in the recycling program may be the establishment of inflexible policies that fail to take the different levels of economic development and population development in different regions into account [

10]. In Chinese cities, 3.3–5.6 million people (0.56–0.93% of the urban population) produce waste as a result of their participation in the informal sector [

11]. The impact of the informal sector on the environment is twofold. On the one hand, the informal sector can reduce the cost of waste disposal and create more jobs. On the other hand, the non-standard methods of waste disposal used by this sector may cause the further deterioration of the environment; in turn, this may increase the likelihood of developing common health problems by 1.7 times [

12]. Therefore, in order to change the current situation and improve residents’ participation in recycling programs, it is crucial to understand the factors influencing their non-participation.

Many researchers have explored the factors influencing residents’ participation in the waste sorting process. A person’s participation in waste sorting, recycling, waste collection, and waste treatment processes is most directly affected by their intention to participate in these processes [

13]. Various studies have illustrated the internal factors that prompt people to move from intention to behavior; these include subjective norms, a person’s attitude, a person’s sense of belonging, and the perceived convenience of performing a certain action, among others [

14,

15]. Some scholars have found that the influence of external factors on a person’s intrinsic motivations further stimulate the likelihood that they will act on their intentions to implement pro-environmental behaviors [

16].

Moreover, the likelihood of a person engaging in behaviors that assist with the waste sorting process is determined by their external environment, which is created independently of the individual. The external factors exerting pressure on people’s behaviors mainly include social governance, economic incentives, social norms, infrastructure convenience, and so on. Occasionally, scholars reach different conclusions about the individual effects of these factors. Areas that have rapidly developing regional economies, for instance, tourism hubs, produce more waste, which is not conducive to the waste sorting process [

17]. Furthermore, higher taxes always means more investment in infrastructure. Infrastructure has a positive, moderating effect on the relationship between willingness and behavior [

18]. Different aspects of infrastructure, such as design preferences, physical designs, and visual prompts, also have a significant effect on public participation [

19]. Moreover, urban policies play a crucial role in whether people decide to participate in the waste sorting process; indeed, differences in the population, the unemployment rate, and geographical factors cannot be ignored [

17]. Some studies have shown that people living in areas with waste sorting policies showed higher levels of participation in waste sorting activities than people living in areas without waste sorting policies; furthermore, knowledge of the waste sorting process, and a willingness to participate, have a mediating effect on the participation levels [

10]. Policies offering financial incentives are very effective; however, regarding such policies, participation levels are influenced by the interpersonal relationships in a community. For example, in communities with a strong, volunteering ethos, financial incentives can negatively affect recycling performance [

20]. Legislation and education can also affect the participation rate by improving the values and beliefs in a population; for instance, it may impact the level of responsibility that people may feel toward their own waste production habits. Nevertheless, legislation and education can also have different spillover effects on the participation rate [

21]. To sum up, the factors influencing public participation are not always consistent.

Regarding the abovementioned influencing factors, scholars have tended to study the one-way linear effect of residents’ participation behavior; few previous studies have focused on the interactions between these factors. Indeed, Khalil et al. examined the interaction between digital precision and the manner in which information is framed and the impact it had on residents’ awareness of food waste [

22]. Chen et al. explored the interaction between information and the perceived convenience of performing a certain action and the impact it had on waste separation behavior [

23]. Most research concerning methods of adequacy and necessity tend to be focused on enterprise management and decision-making [

24]; moreover, such research is also used to help make policy decisions, among other things [

25]. In this paper, a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods are used to study the interactions between external factors affecting the residents’ participation in waste sorting; these methods include the necessary condition analysis (NCA) and the fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). There are strong reasons for choosing methods such as the NCA and fsQCA. The NCA method was applied in order to measure sustainable behavior [

26], the mediating effects on participation levels [

27], and so on. Furthermore, prior to this study, the NCA had not been applied to studies focusing on waste classification behavior. We believe that this method provides a novel theoretical and statistical basis for analysis. The FsQCA method has been widely used in business management [

28] and information management [

29]. It is suitable for both multiple attribute variable investigations and specific case details [

30]. China’s territory is vast, and the development rate of its waste management infrastructure is not the same in different regions. Combining the two methods ensures the completeness and robustness of the results. It is helpful to understand the complex relationships between the different external factors affecting residents’ behavior with regard to waste sorting.

Some achievements have been made in studies that focus on MSW and recycling behavior. However, there are still some shortcomings, which are as follows: (1) previous research has investigated the factors directly influencing waste classification and recycling behaviors; however, such investigations were one dimensional in that they failed to account for multiple external environmental factors and the effect that they have on residents’ participation in waste sorting and recycling; and (2) most studies failed to consider the interactions between external factors and their effects on residents’ waste classification and recycling behaviors. The research questions of this study are as follows: What are the external factors that affect residents’ waste classification behavior? How do these factors interact with one another? Based on these problems, a new model to assess the factors influencing residents’ waste classification and recycling behaviors was constructed in order to explore how to influence residents’ waste sorting behavior in the future.

More specifically, we focused on the issue of resident participation in sorting waste, noting whether it was sorted as it was generated. The pilot cities have different resources and conditions, and the governing bodies of each city have also chosen different policies with which to implement proper waste management; therefore, this study aims to assess the current waste classification practices of residents and whether they participate in those practices. Additionally, with a focus on the pilot cities in China that have these waste classification systems, this study identifies the interactions between the key influencing factors. Most studies examining these influencing factors have focused on the single linear effects of residents’ participation in the MSW. Few studies have studied the sufficiency and necessity of these factors, nor the interactions between them; therefore, this study provides empirical examples for governments in regions with different circumstances in order to promote further public participation in waste sorting processes. The following sections are structured as follows: section two details the manner in which our hypotheses were developed; section three introduces the methods through which we collected data and conducted analyses; section four describes the results of our data analyses, and furthermore, the results are verified; the results, future implications, and prospects for future research are discussed in section five; and finally, section six details our conclusion.

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Research Results

In this study, we assessed the impact of external factors on residents and their participation in waste sorting. In accordance with the NCA results, no single conditional variable constitutes the core factor prompting residents to participate, or not participate, in the waste sorting process; then, we used the fsQCA method to distinguish between the configuration paths. As per the results, there are two main combinations of factors that can achieve a high participation rate: high environmental quality together with few advocacy policies, and many advocacy policies together with high convenience. Moreover, we found that the main reason for the low participation rate is poor environmental quality. Other reasons include the inconvenience of MSW and policy problems. Overall, no single factor is sufficient or necessary to explain the participation rates concerning waste sorting.

The main pathway culminating in a high participation rate comprised the following combination of factors: high environmental quality and few advocacy policies. Both H1 and H2 comprise cases wherein cities exhibit a low economic performance, and less waste is produced as a result of household consumption. In these cities, the process of waste sorting is slow, and local government policies tend to be based on publicity and education. Advocacy policies concerning environmental quality influence residents’ participation in recycling processes; however, other policies could still be more effective. This result is similar to previous findings [

72]. Based on the utility perception theory, a determinant of classification behavior is the perception that one may receive personal rewards, not only in terms of harvesting certain benefits, but also in terms of achieving a certain goal [

73]. Good environmental quality will increase people’s confidence in waste sorting. Tongling is a typical example of a city following path H1. In the absence of too many mandatory policies, Tongling has a high participation rate; this is due to the fact that 1374 household waste classification centers have been built, and thus, the coverage rate concerning residential facilities reached 100%. H2 indicates that convenience may also be considered as an edge condition. Nanning and Lanzhou are the representative cities following this path. Since 2021, the allocation rate of household waste classification facilities in Nanning has reached 100%, with more than 1000 waste collection and transportation vehicles allocated for waste classification purposes, in accordance with the four categories of waste. Moreover, as per the responsibility of the sanitation station, if there is unclassified waste, the station can input the two-digit code that alerts the authorities who are tasked with fine management.

The second main pathway culminating in high participation comprises the following combination of factors: high levels of convenience and a high number of advocacy policies. This conclusion is consistent with previous findings in the literature [

74]. Incentive-based recycling policies have a ‘crowding out’ effect, and this can negatively impact other waste policies by reducing public support for other waste policies; however, the prescience of advocacy policies will disappear as other policies expire [

75]. Moreover, H3 and H4 show different results when subjected to other conditions. This suggests that a high number of compulsory policies is not necessary; this finding differs with some studies [

41]. H3 is always suitable for large cities that have a robust economy together with adequate infrastructure and a good waste management system. Cities that follow H3 include Beijing, Shanghai, and Qingdao. In 2015, Qingdao generated 2.21 million tons of municipal solid waste, which increased to 3.1 million tons in 2020, and it will increase to 6.5 million tons in 2035 [

76]. The average efficiency of waste collection in these cities, in accordance with the standards of the four categories, was 75.7% [

77]. An efficient recycling system reduces the cost of recycling. H4 illustrates that incentive-based policies, including smart device investments and returns in the form of points or cash, play a significant role in promoting participation in waste sorting. Typical cities that follow H4 include Changchun. Changchun has established a waste collection network comprising mobile trucks, which is an informal recycling model that recycles 95–96% of the waste [

78]. This mode of waste collection integrates individual and household recycling; it not only improves residents’ enthusiasm toward waste sorting, but it also provides economic benefits for these individuals. This waste collection process is conducive to forming habits and routines relating to recycling waste.

We also examined the combination of urban conditions that produce low participation rates. NH1 and NH2 represent low environmental quality, and the combination of factors that produce low participation rates are as follows: few mandatory policies and low levels of convenience. This shows that without a waste recovery system, neither a nice living environment nor strong policy guidance can prompt residents to spontaneously separate their waste. NH3 shows that poor environmental quality and back-end waste disposal leads to residents having less confidence in the waste classification result. This is in line with existing research focusing on developing countries, such as the Philippines, despite efforts by cities to implement effective measures that comply with legal regulations. Failures of waste management in this country are due to the lack of disposal facilities, including a lack of adequate soil cover and sanitary landfills for non-biodegradable materials [

79].

5.2. Future Implications

From the results, the effect of a single causal condition may be positive or negative, depending on how it is combined with other conditions. Based on the above results, this study proposes the following policy recommendations. In order to increase the participation of residents in waste sorting, the combination of measures (such as those pertaining to environmental quality, infrastructure, and economic level) needs to be differentiated and flexible to match local objective conditions; for example, in cities with rapid economic development, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Qingdao, more convenient facilities should be built to minimize the time spent depositing waste, and more sorting points should be set up to minimize the time spent and the economic costs incurred by residents. Furthermore, launching sorting points to exchange equipment and bestow economic rewards or honors on enterprises and individuals who demonstrate excellent levels of waste sorting would be an effective measure.

For cities with low levels of economic development, such as Lanzhou, improving residents’ happiness is a better way to effectively improve environmental quality. As citizens become increasingly aware of the relationship between the environment and their own health, as a bottom-up approach, public participation cultivates the residents’ sense of identity and responsibility [

80]; however, groups belonging to a lower socioeconomic bracket tend to spend less time on recycling activities because they have more pressing needs. Therefore, their sensitivity to policies is weak. On the other hand, financial incentives can be effective drivers for low-income households as they might benefit from the sale of recyclable materials. Positive fiscal incentives are easy to accept, but negative incentives (such as taxes and fees) are counterproductive. In addition, although these municipalities have implemented mandatory sorting policies and even fines, the entities that must abide by such measures are collectives and organized waste producers. In fact, individual residents are not subject to punishment. At the community level, due to the lack of effective implementation and supervision, despite any previous potential effort, waste is mixed once again, and residents lose their enthusiasm and confidence in the sorting process.

A high number of compulsory policies does not necessarily achieve a high participation rate. In accordance with our results, GDP levels are usually accompanied by compulsory government policies. Cities with high GDPs usually mean better infrastructure and more experience and leadership with regard to waste recycling; therefore, governments often adopt strong enforcement policies. However, in the long-term, it is difficult to maintain a high participation rate with only strong policies. Policies emphasizing punishment should be used with caution because of the risk of negative spillover effects [

81]. The government should devise waste sorting policies in accordance with the characteristics of different regions, delivering waste classification education in schools, and raising awareness of waste sorting in the community, among other activities.

In accordance with the results of the existing research, an important driver behind consumers’ waste classification behavior is environmental concern (such as satisfaction with environmental quality, based on the “broken window theory”), and the most important barriers are a lack of knowledge and understanding, as well as a lack of opportunity, inconvenience, and task difficulty [

75]; therefore, the government should emphasize the promotion of waste classification methods for the whole of society, and it should urge them to fulfill their social responsibilities. The government can strengthen the environmental awareness of residents through various channels, in accordance with the characteristics of the region. Waste-related activities and information must coalesce with people’s daily activities and concerns, so that households have a clear recycling plan and know what, where, when, and how to recycle. Paying more attention to improving residents’ awareness of what environmental concerns exist, and removing barriers so that residents can participate in waste sorting, may help to improve the participation rate.

5.3. Strengths and Limitations

This paper makes the following contributions. First, we adopted a hybrid method, combining NCA and fsQCA, to analyze the complex causalities between external factors and residents’ participation in waste classification; this is conducive to promoting the development of studies concerning the necessary and sufficient relationships between the factors behind the participation rate. Second, although previous studies have discussed the factors influencing residents’ participation in waste sorting, this paper is an empirical study that examines the interaction between external factors influencing the residents of pilot cities from various aspects. It explores four pathways that achieve a high participation rate, thus expanding the research concerning residents’ participation in waste sorting in developing countries. Third, this paper provides a comprehensive insight into the different developmental stages of waste sorting policies, as well as the advantages of these policies; therefore, it can provide inspiration for policy choices in this field.

There are still some limitations of this paper, which are worthy of further study. First, limited by the availability of data, we only analyzed the pathways concerning the participation rate of some urban residents who first implemented waste classification policies; hence, in future studies, we can obtain more sufficient data via questionnaires and surveys, and thus, further understand the psychological factors behind participation in the waste sorting process, as well as improve the configuration of the pathways. Further analysis of such configurations can be conducted in the future. Moreover, we only discussed planar static data; in future studies, we can further examine the temporal and spatial correlation. In addition, we will also pay attention to the effective changes in residents’ behavior brought about by the policies.

6. Conclusions

This study focuses on the problem of resident participation in waste sorting in pilot cities in China. It provides an in-depth analysis of the differences between the pathways in the literature concerning MSW. The analysis of waste classification clarifies the impact of external factors on residents’ participation in the waste sorting process, and it provides an outline of different waste management practices in areas with different resource and development patterns. As China intends to achieve carbon neutrality and establish a circular economy, analyzing participation in waste classification is of great value. Combining NCA and fsQCA methods, this study empirically studied the external factors relating to waste management in Chinese cities by configuring a combination of factors. This paper makes the following conclusions:

First, the NCA method was adopted, and it found that no single external factor constitutes a necessary condition for a high participation rate; however, improving environmental quality can make a significant contribution. This means that the complex issue of participation in waste sorting needs to be studied from an integrated perspective that takes external factors into account.

Second, fsQCA analysis also proved the asymmetry of causality. We found four pathways that demonstrate how to achieve a high participation rate. These reflect the multiple ways in which a high participation rate can be achieved in different cities. Convenience always tends to have a positive effect on the participation rate. Moreover, environmental quality and economic factors have different effects on different pathways. In terms of core factors, H1 and H2, H3, and H4 share the same core conditions; therefore, they are divided into environment-driven pathways and resource-driven pathways. An environment-driven pathway does not require advocacy policies, whereas a resource-driven pathway requires a combination of advocacy policies and convenience. In addition, whether economic factors and compulsory policies constitute marginal conditions depends on their presence or absence in H3 and H4; however, they remain consistent in their respective pathways.

Third, in the configurations NH1 and NH2, which comprise conditions that contribute to low participation rates, environmental quality appears to be a core variable, accompanied by compulsory and advocacy policies. In particular, for NH3, even if all other variables are present, the lack of convenience directly leads to low participation rates.

= core conditions exist;

= core conditions exist;  = lack of core conditions; • = edge conditions exist; and ⊗ = missing edge conditions.

= lack of core conditions; • = edge conditions exist; and ⊗ = missing edge conditions.