The Role of Health Information Sources on Cervical Cancer Literacy, Knowledge, Attitudes and Screening Practices in Sub-Saharan African Women: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Study Screening and Selection

2.4. Data Extraction Process

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

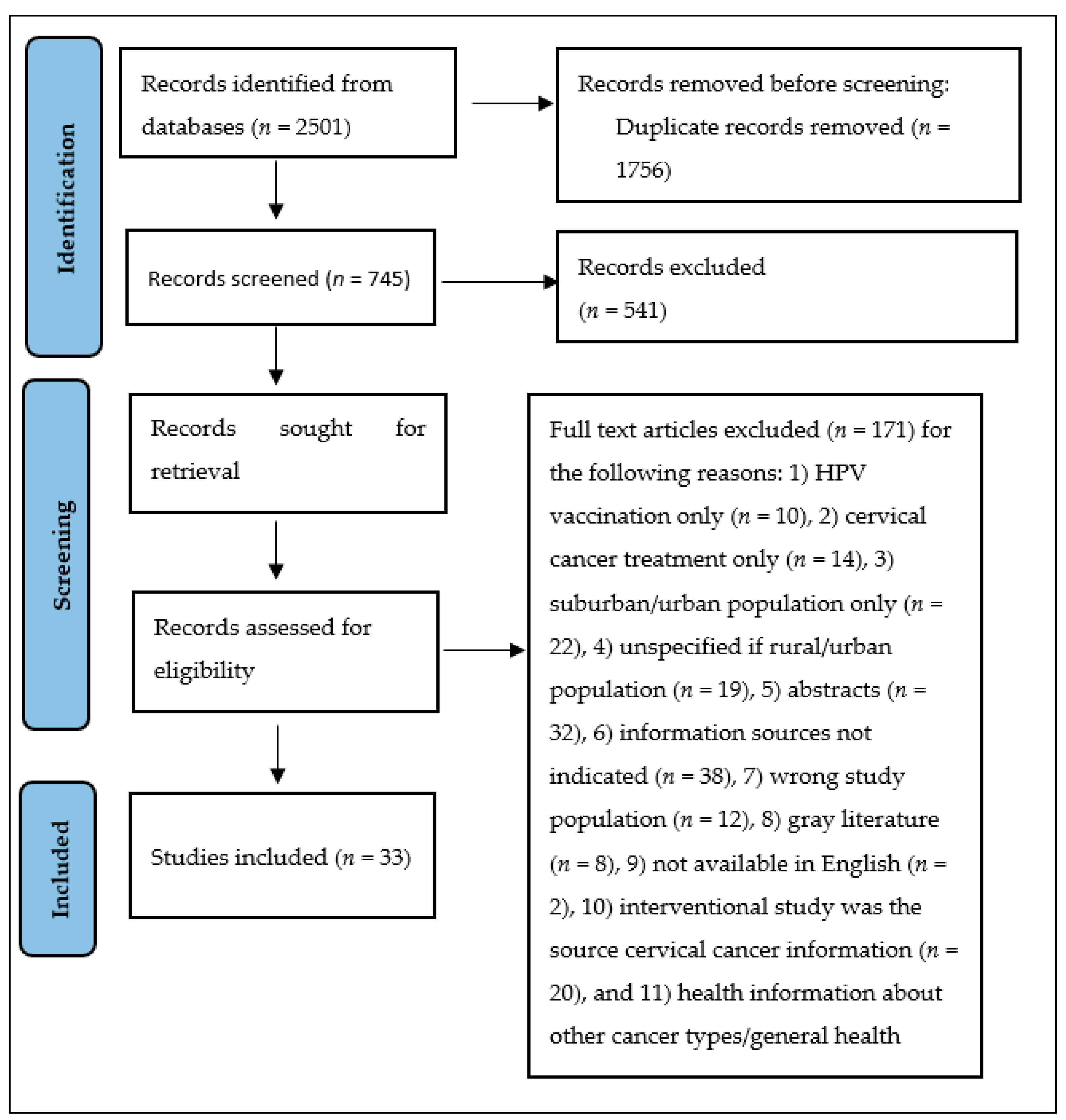

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Features of Included Studies

3.3. Quality Appraisal

3.4. Sources of Information on CC and CCS

3.5. Correlation of Information Sources with CC Knowledge, Literacy, Screening Uptake and Attitudes toward CC and CCS

3.5.1. CC Information Sources and CCS

3.5.2. CC Information Sources and CC Knowledge

3.5.3. CC Information and CC Literacy

3.5.4. Sources of CC Information and Screening Attitudes

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | ((“Uterine Cervical Neoplasms” [Mesh] OR “cervical cancer*” OR “cervical neoplasm*” OR “cervix neoplasm*” OR “cervix cancer*” OR “cancer of the cervix”) AND (“Consumer Health Information” [Mesh] OR “health information” OR “health literacy” OR “information” [tiab] OR “literacy” [tiab])) AND (“Africa South of the Sahara” [Mesh] OR “Africa South of the Sahara” [tiab] OR “Africa, Central” [tiab] OR “Cameroon” [tiab] OR “Central African Republic” [tiab] OR “Chad” [tiab] OR “Congo” [tiab] OR “Democratic Republic of the Congo” [tiab] OR “Equatorial Guinea” [tiab] OR “Gabon” [tiab] OR “Sao Tome and Principe” [tiab] OR “Africa, Eastern” [tiab] OR “Burundi” [tiab] OR “Djibouti” [tiab] OR “Eritrea” [tiab] OR “Eswatini” [tiab] OR “Ethiopia” [tiab] OR “Kenya” [tiab] OR “Rwanda” [tiab] OR “Somalia” [tiab] OR “South Sudan” [tiab] OR “Sudan” [tiab] OR “Tanzania” [tiab] OR “Uganda” [tiab] OR “Africa, Southern” [tiab] OR “Angola” [tiab] OR “Botswana” [tiab] OR “Eswatini” [tiab] OR “Lesotho” [tiab] OR “Malawi” [tiab] OR “Mozambique” [tiab] OR “Namibia” [tiab] OR “South Africa” [tiab] OR “Zambia” [tiab] OR “Zimbabwe” [tiab] OR “Africa, Western” [tiab] OR “Benin” [tiab] OR “Burkina Faso” [tiab] OR “Cabo Verde” [tiab] OR “Cote d’Ivoire” [tiab] OR “Gambia” [tiab] OR “Ghana” [tiab] OR “Guinea” [tiab] OR “Guinea-Bissau” [tiab] OR “Liberia” [tiab] OR “Mali” [tiab] OR “Mauritania” [tiab] OR “Niger” [tiab] OR “Nigeria” [tiab] OR “Senegal” [tiab] OR “Sierra Leone” [tiab] OR “Togo” [tiab] OR “Swaziland” [tiab]) |

| Embase | (‘uterine cervix cancer’/exp OR ‘cervical cancer*’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘cervical neoplasm*’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘cervix neoplasm*’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘cervix cancer*’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘cancer of the cervix’:ti,ab,kw) AND (‘medical information’/exp OR ‘health literacy’/exp OR ‘consumer health information’/exp OR information:ti,ab,kw OR literacy:ti,ab,kw) AND (‘africa south of the sahara’/exp OR ‘africa south of the sahara’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘africa, central’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘cameroon’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘central african republic’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘chad’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘congo’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘democratic republic of the congo’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘equatorial guinea’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘gabon’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘sao tome and principe’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘africa, eastern’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘burundi’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘djibouti’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘eritrea’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘ethiopia’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘kenya’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘rwanda’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘somalia’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘south sudan’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘sudan’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘tanzania’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘uganda’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘africa, southern’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘angola’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘botswana’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘eswatini’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘lesotho’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘malawi’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘mozambique’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘namibia’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘south africa’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘zambia’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘zimbabwe’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘africa, western’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘benin’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘burkina faso’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘cabo verde’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘cote d ivoire’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘gambia’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘ghana’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘guinea’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘guinea-bissau’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘liberia’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘mali’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘mauritania’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘niger’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘nigeria’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘senegal’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘sierra leone’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘togo’:ti,ab,kw) |

| Web of Science | ((ALL = (“cervical cancer*” OR “cervical neoplasm*” OR “cervix neoplasm*” OR “cervix cancer*” OR “cancer of the cervix”)) AND ALL = (information OR literacy)) AND TS = ((“Africa South of the Sahara” OR “Central Africa” OR Cameroon OR “Central African Republic” OR Chad OR Congo OR “Democratic Republic of the Congo” OR “Equatorial Guinea” OR Gabon OR “Eastern Africa” OR Burundi OR Djibouti OR Eritrea OR Ethiopia OR Kenya OR Rwanda OR Somalia OR “South Sudan” OR Sudan OR Tanzania OR Uganda OR “Southern Africa” OR Angola OR Botswana OR Lesotho OR Malawi OR Mozambique OR Namibia OR “South Africa” OR Swaziland OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe OR “Western Africa” OR Benin OR “Burkina Faso” OR “Cape Verde” OR “Cote d’Ivoire” OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guinea OR “Guinea-Bissau” OR Liberia OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Senegal OR “Sierra Leone” OR Togo OR Eswatini)) |

| CINAHL (Ebsco Host) | (MH “Cervix Neoplasms + ”) OR ( “cervical cancer*” OR “cervical neoplasm*” OR “cervix neoplasm*” OR “cervix cancer*” OR “cancer of the cervix” ) AND (MH “Health Information + ”) OR ( “information” OR “literacy” ) AND (MH “Africa South of the Sahara+”) OR ( “Africa South of the Sahara” OR “Africa, Central” OR “Cameroon” OR “Central African Republic” OR “Chad” OR “Congo” OR “Democratic Republic of the Congo” OR “Equatorial Guinea” OR “Gabon” OR “Sao Tome and Principe” OR “Africa, Eastern” OR “Burundi” OR “Djibouti” OR “Eritrea” OR “Ethiopia” OR “Kenya” OR “Rwanda” OR “Somalia” OR “South Sudan” OR “Sudan” OR “Tanzania” OR “Uganda” OR “Africa, Southern” OR “Angola” OR “Botswana” OR “Eswatini” OR “Lesotho” OR “Malawi” OR “Mozambique” OR “Namibia” OR “South Africa” OR “Zambia” OR “Zimbabwe” OR “Africa, Western” OR “Benin” OR “Burkina Faso” OR “Cape Verde” OR “Cote d’Ivoire” OR “Gambia” OR “Ghana” OR “Guinea” OR “Guinea-Bissau” OR “Liberia” OR “Mali” OR “Mauritania” OR “Niger” OR “Nigeria” OR “Senegal” OR “Sierra Leone” OR “Togo”) |

References

- Dzinamarira, T.; Moyo, E.; Dzobo, M.; Mbunge, E.; Murewanhema, G. Cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: An urgent call for improving accessibility and use of preventive services. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 33, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Boily, M.-C.; Rönn, M.M.; Obiri-Yeboah, D.; Morhason-Bello, I.; Meda, N.; Lompo, O.; Mayaud, P.; Pickles, M.; Brisson, M.; et al. Regional and country-level trends in cervical cancer screening coverage in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic analysis of population-based surveys (2000–2020). PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gafaranga, J.P.; Manirakiza, F.; Ndagijimana, E.; Urimubabo, J.C.; Karenzi, I.D.; Muhawenayo, E.; Gashugi, P.M.; Nyirasebura, D.; Rugwizangoga, B. Knowledge, Barriers and Motivators to Cervical Cancer Screening in Rwanda: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Women’s Health 2022, 14, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.; Clark, M.D.; Collins, Z.; Traore, F.; Dioukhane, E.M.; Thiam, H.; Ndiaye, Y.; De Jesus, E.L.; Danfakha, N.; Peters, K.E.; et al. Cervical cancer screening decentralized policy adaptation: An African rural-context-specific systematic literature review. Glob. Health Action 2019, 12, 1587894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayamolowo, S.J.; Akinrinde, L.F.; Oginni, M.O.; Ayamolowo, L.B. The Influence of Health Literacy on Knowledge of Cervical Cancer Prevention and Screening Practices among Female Undergraduates at a University in Southwest Nigeria. Afr. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2020, 22, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosser, J.I.; Hamisi, S.; Njoroge, B.; Huchko, M.J. Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening in Rural Kenya: Perspectives from a Provider Survey. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, T.S.; Moodley, J.; Walter, F.M. Population risk factors for late-stage presentation of cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zibako, P.; Hlongwa, M.; Tsikai, N.; Manyame, S.; Ginindza, T.G. Mapping evidence on management of cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: Scoping review protocol. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J. Cancer/health communication and breast/cervical cancer screening among Asian Americans and five Asian ethnic groups. Ethn. Health 2018, 25, 960–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudjoe, J.; Gallo, J.J.; Sharps, P.; Budhathoki, C.; Roter, D.; Han, H.-R. The Role of Sources and Types of Health Information in Shaping Health Literacy in Cervical Cancer Screening Among African Immigrant Women: A Mixed-Methods Study. HLRP Health Lit. Res. Pr. 2021, 5, e96–e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatumo, M.; Gacheri, S.; Sayed, A.-R.; Scheibe, A. Women’s knowledge and attitudes related to cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening in Isiolo and Tharaka Nithi counties, Kenya: A cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsegay, A.; Araya, T.; Amare, K.; G/Tsadik, F. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice on Cervical Cancer Screening and Associated Factors Among Women Aged 15-49 Years in Adigrat Town, Northern Ethiopia, 2019: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Women’s Health 2020, 12, 1283–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatho, A.; Bikaitwoha, M.E.; Mugisha, N.M. Socio-culturally mediated factors and lower level of education are the main influencers of functional cervical cancer literacy among women in Mayuge, Eastern Uganda. Ecancermedicalscience 2020, 14, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dozie, U.W.; Elebari, B.L.; Nwaokoro, C.J.; Iwuoha, G.N.; Emerole, C.O.; Akawi, A.J.; Chukwuocha, U.M.; Dozie, I.N.S. Knowledge, attitude and perception on cervical cancer screening among women attending ante-natal clinic in Owerri west L.G.A, South-Eastern Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2021, 28, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruddies, F.; Gizaw, M.; Teka, B.; Thies, S.; Wienke, A.; Kaufmann, A.M.; Abebe, T.; Addissie, A.; Kantelhardt, E.J. Cervical cancer screening in rural Ethiopia: A cross-sectional knowledge, attitude and practice study. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squiers, L.; Peinado, S.; Berkman, N.; Boudewyns, V.; McCormack, L. The Health Literacy Skills Framework. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innovation, V.H. Covidence Systematic Review Software. Melbourne, Australia. 2023. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Tufanaru, C.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Mu, P. Conducting systematic reviews of association (etiology). Int. J. Evid.-Based Health 2015, 13, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, K.; Oketch, S.Y.; Choi, Y.; Huchko, M.J. Female perspectives on male involvement in a human-papillomavirus-based cervical cancer-screening program in western Kenya. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyambe, N.; Hoover, S.; Pinder, L.F.; Chibwesha, C.J.; Kapambwe, S.; Parham, G.; Subramanian, S. Differences in Cervical Cancer Screening Knowledge and Practices by HIV Status and Geographic Location: Implication for Program Implementation in Zambia. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2018, 22, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Osei, E.A.; Appiah, S.; Gaogli, J.E.; Oti-Boadi, E. Knowledge on cervical cancer screening and vaccination among females at Oyibi Community. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ports, K.A.; Reddy, D.M.; Rameshbabu, A. Cervical Cancer Prevention in Malawi: A Qualitative Study of Women’s Perspectives. J. Health Commun. 2014, 20, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compaore, S.; Ouedraogo, C.M.R.; Koanda, S.; Haynatzki, G.; Chamberlain, R.M.; Soliman, A.S. Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening in Burkina Faso: Needs for Patient and Professional Education. J. Cancer Educ. 2015, 31, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, M.S.; Skrastins, E.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Jindal, P.; Oneko, O.; Yeates, K.; Booth, C.M.; Carpenter, J.; Aronson, K.J. Cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccine acceptability among rural and urban women in Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e005828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kubber, M.M.; Peters, A.A.W.; Soeters, R.P. Investigating cervical cancer awareness: Perceptions of the Female Cancer Programme in Mdantsane, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2011, 3, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endalew, D.A.; Moti, D.; Mohammed, N.; Redi, S.; Alemu, B.W. Knowledge and practice of cervical cancer screening and associated factors among reproductive age group women in districts of Gurage zone, Southern Ethiopia. A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezem, B. Awareness and uptake of cervical cancer screening in Owerri, South-Eastern Nigeria. Ann. Afr. Med. 2007, 6, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebisa, T.; Bala, E.T.; Deriba, B.S. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Toward Cervical Cancer Screening Among Women Attending Health Facilities in Central Ethiopia. Cancer Control 2022, 29, 10732748221076680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isabirye, A.; Mbonye, M.K.; Kwagala, B. Predictors of cervical cancer screening uptake in two districts of Central Uganda. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangmennaang, J.; Thogarapalli, N.; Mkandawire, P.; Luginaah, I. Investigating the disparities in cervical cancer screening among Namibian women. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 138, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasa, A.S.; Tesfaye, T.D.; Temesgen, W.A. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards cervical cancer among women in Finote Selam city administration, West Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region, North West Ethiopia, 2017. Afr. Health Sci. 2018, 18, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimondo, F.C.; Kajoka, H.D.; Mwantake, M.R.; Amour, C.; Mboya, I.B. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of cervical cancer screening among women living with HIV in the Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania. Cancer Rep. 2021, 4, e1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mruts, K.B.; Gebremariam, T.B. Knowledge and Perception Towards Cervical Cancer among Female Debre Berhan University Students. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2018, 19, 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukama, T.; Ndejjo, R.; Musabyimana, A.; Halage, A.A.; Musoke, D. Women’s knowledge and attitudes towards cervical cancer prevention: A cross sectional study in Eastern Uganda. BMC Women’s Health 2017, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwantake, M.R.; Kajoka, H.D.; Kimondo, F.C.; Amour, C.; Mboya, I.B. Factors associated with cervical cancer screening among women living with HIV in the Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania: A cross-sectional study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 30, 101985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndejjo, R.; Mukama, T.; Musabyimana, A.; Musoke, D. Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening and Associated Factors among Women in Rural Uganda: A Cross Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimande-Joel, R.; Ekenedo, G.O. Knowledge, Belief and Practice of Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention among Women of Taraba, North-East Nigeria. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 3291–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, A.; Segni, M.T.; Demissie, H.F. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) toward Cervical Cancer Screening among Adama Science and Technology University Female Students, Ethiopia. Int. J. Breast Cancer 2022, 2022, 2490327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafere, Y.; Jemere, T.; Desalegn, T.; Melak, A. Women’s knowledge and attitude towards cervical cancer preventive measures and associated factors In South Gondar Zone, Amhara Region, North Central Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Arch. Public. Health 2021, 79, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapera, O.; Kadzatsa, W.; Nyakabau, A.M.; Mavhu, W.; Dreyer, G.; Stray-Pedersen, B.; Sjh, H. Sociodemographic inequities in cervical cancer screening, treatment and care amongst women aged at least 25 years: Evidence from surveys in Harare, Zimbabwe. BMC Public. Health 2019, 19, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekle, T.; Wolka, E.; Nega, B.; Kumma, W.P.; Koyira, M.M. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Towards Cervical Cancer Screening Among Women and Associated Factors in Hospitals of Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakwoya, E.B.; Gemechu, K.S.; Dasa, T.T. Knowledge of Cervical Cancer and Associated Factors Among Women Attending Public Health Facilities in Eastern Ethiopia. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 10103–10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldu, B.F.; Lemu, L.G.; Mandaro, D.E. Comprehensive Knowledge towards Cervical Cancer and Associated Factors among Women in Durame Town, Southern Ethiopia. J. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020, 2020, 4263439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiiti, T.A.; Bogers, J.; Lebelo, R.L. Knowledge of Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer among Women Attending Gynecology Clinics in Pretoria, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perng, P.; Perng, W.; Ngoma, T.; Kahesa, C.; Mwaiselage, J.; Merajver, S.D.; Soliman, A.S. Promoters of and barriers to cervical cancer screening in a rural setting in Tanzania. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 123, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanto, S.Y.; Belachew, T.; Wordofa, M.A. Determinants of cervical cancer screening utilization among women in Southern Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gakunga, R.; Ali, Z.; Kinyanjui, A.; Jones, M.; Muinga, E.; Musyoki, D.; Igobwa, M.; Atieno, M.; Subramanian, S. Preferences for Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Among Women and Men in Kenya: Key Considerations for Designing Implementation Strategies to Increase Screening Uptake. J. Cancer Educ. 2023, 38, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.R.; Baril, N.C.; Achille, E.; Foster, S.; Johnson, N.; Taylor-Clark, K.; Gagne, J.J.; Olukoya, O.; Huisingh, C.E.; Ommerborn, M.J.; et al. Trust Yet Verify: Physicians as Trusted Sources of Health Information on HPV for Black Women in Socioeconomically Marginalized Populations. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2014, 8, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awofeso, O.; Roberts, A.A.; Salako, O.; Balogun, L.; Okediji, P. Prevalence and pattern of late-stage presentation in women with breast and cervical cancers in Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. Niger. Med. J. 2018, 59, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekalign, T.; Teshome, M. Prevalence and determinants of late-stage presentation among cervical cancer patients, a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.O.; Mullins, R.M.; Siahpush, M.; Spittal, M.J.; Wakefield, M. Mass media campaign improves cervical screening across all socio-economic groups. Health Educ. Res. 2009, 24, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Macarthur, G.J.; Wright, M.; Beer, H.; Paranjothy, S. Impact of media reporting of cervical cancer in a UK celebrity on a population-based cervical screening programme. J. Med. Screen. 2011, 18, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bien-Aimé, D.D.R. Understanding the Barriers and Facilitators to Cervical Cancer Screening Among Women in Gonaives, Haiti, An Explanatory Sequential MixedMethods Study. Master’s Thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume, D.; Amédée, L.M.; Rolland, C.; Duroseau, B.; Alexander, K. Exploring engagement in cervical cancer prevention services among Haitian women in Haiti and in the United States: A scoping review. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2022, 41, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holst, C.; Sukums, F.; Radovanovic, D.; Ngowi, B.; Noll, J.; Winkler, A.S. Sub-Saharan Africa—The new breeding ground for global digital health. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, e160–e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FurtherAfrica. African Countries with the Highest Number of Mobile Phones. 2022. Available online: https://furtherafrica.com/tag/african-countries-with-the-highest-number-of-mobile-phones/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Wyche, S.; Simiyu, N.; Othieno, M.E. Understanding women’s mobile phone use in rural Kenya: An affordance-based approach. Mob. Media Commun. 2018, 7, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudjoe, J.; Budhathoki, C.; Roter, D.; Gallo, J.J.; Sharps, P.; Han, H.-R. Exploring Health Literacy and the Correlates of Pap Testing Among African Immigrant Women: Findings from the AfroPap Study. J. Cancer Educ. 2021, 36, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducray, J.F.; Kell, C.M.; Basdav, J.; Haffejee, F. Cervical cancer knowledge and screening uptake by marginalized population of women in inner-city Durban, South Africa: Insights into the need for increased health literacy. Women’s Health 2021, 17, 17455065211047141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azolibe, C.B.; Okonkwo, J.J. Infrastructure development and industrial sector productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Econ. Dev. 2020, 22, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Citation | Country | Study Participants | Study Setting | Study Design and Sampling | Cervical Cancer (CC) Information Sources and Preferences | Screening Practices, CC Knowledge, and Attitudes toward CC and Cervical Cancer Screening (CCS) | Association of Information Source with Cervical Cancer Screening Uptake, Knowledge, Literacy, and Screening Attitudes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gafaranga et al., 2022 [3] | Rwanda | Women (N = 30) aged 30–59 years; other demographics unspecified | Rural = 16 (53.3%) and urban = 14 (46.7%) | Qualitative | Motivators for the use of screening services were personal (7), family members and friends (7), healthcare professionals (8), and government officials (SMS from telecommunication, radio, TV) (12). | Screening: Uptake not reported. Barriers to screening were pain/fear of a positive diagnosis (N = 26), high cost (N = 18), lack of information (N = 10), lack of insurance (N = 6), administrative barrier (absence of materials), and lack of accessible services (long distance to health facility (N = 3). Attitudes: Not studied Knowledge: Approx. 83% were aware of CC: 57% aware of prevention measures, and 77% had some knowledge/had heard of CCS. | Not applicable: qualitative study |

| Gatumo M et al., 2018 [11] | Kenya | Women (N = 451) ages 18–85 years selected using multi-stage cluster sampling: 14.2% were non-literate, 5.1% could read and write, though with no formal education, and 80.7% had a primary level of education or higher. | “Predominantly rural” | Descriptive cross-sectional | Approx. 79.8% (N = 360) of participants had heard about cervical cancer, and 15.1% (N = 301) had heard about HPV. Primary sources of information were family and friends (45.0%, n = 162), followed by a healthcare facility (40.3%, n = 145), radio/television (40.6%, n = 146), and less than 6.0% (n = 20) stated social media, newspaper, or a non-governmental organization. | Screening: Only 25.6% had ever undergone cervical cancer screening (N = 92). Attitudes: Approx. 89.2% of women who had heard about CC categorized it as “scary”, and 55.8% preferred a female health worker for cervical examination. About two-thirds perceived the examinations positively and believed that healthcare workers performing them were not rude to them. Knowledge: Approx. 80% were aware of CC; 44% scored above average on CC risk factors. Approx. 83.6% of women aware of CC had heard about CCS. | Not investigated |

| Jatho A et al., 2020 [13] | Uganda | Women (N = 400) aged 18–65 years: 53% (N = 212) with primary education level and 47% (N = 188) had a post-primary education level (non-literate participants not included). | Rural | Concurrent mixed methods | Radio, newspaper, mobile phones, health facilities | Screening: Only 24% (N = 96) of individuals had ever been screened for CC, but 99% of them were in the limited CC literacy category. Attitudes: Approx. 56% had intention to screen. Knowledge: Approx. 91% had had limited CC awareness. | Health facility visits during the previous 12 months (p = 0.025) and radio ownership (p = 0.024) were associated with cervical cancer literacy. Mobile phone ownership and newspaper reading frequency were not significantly associated with CC literacy. The relationship between information sources and CC screening was not investigated. CC screening was not significantly associated with CC literacy (p = 0.204). |

| Dozie et al., 2021 [14] | Nigeria | A random sample of women N (231) ages 15–40 attending antenatal clinic: 14.7% had no formal education, 26.4% had completed primary education, 43.7% had secondary education, and 15.2% had completed post-secondary education. | Rural area | Descriptive cross-sectional | The majority of participants had heard about CC screening (68.8%) from friends (52.85%), family/relatives (38.1%), health center/hospital (5.6%), the Internet (3%), and media (TV, radio, posters, newspapers) (0.4%). Few respondents had basic information on the cause of the disease (19%), prevention (13.9%), risk factors (20.8%), and treatment (23.4%). Approx. 80% of participants were aware of CCS locations. | Screening: Invasion of privacy (34.6%) and high cost of screening (29.4%) were strong reasons for avoiding screening. Attitudes: Only 37.6% were willing to screen. The majority (43%) reported they do not have money to waste on screening, would not get screened because of fear of the result (42%), and saw no need for screening (43.7%). Knowledge: Approx. 69% and 81% were aware of CCS and where to get services, respectively. The majority were not aware that CC is treatable. | Not investigated |

| Ruddies F et al., 2020 [15] | Ethiopia | Women (N = 341), mean age 35.5 years. The majority (63.5%; N = 217) had no formal education; 104—elementary school; 11—beyond 9 years of education; 9—tertiary education. | Rural = 307 (90.3%), urban = 34 (9.7%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Approx. 50% of women had no source of information; nurses (32%), radio (9%), neighbors/community (5%), family (3%), newspaper/tv/poster (1%). | Screening: Only 2.3% (8) of women had been screened before, 70% had the intention to screen, and only 31% had access to a screening facility. Attitudes: Approx. 59% had a negative attitude toward CC and CCS, 13.5% considered themselves at risk for CC, and 61% thought it is a deadly disease. Knowledge: Approx. 36% (125) were aware of CC, 4.7% (14) knew symptoms, none knew HPV is a risk factor for CC. Approx. 88% were interested in learning more about CC. | Women with any source of information on CC and CCS were 9.1 times more likely to have good knowledge (CI:4.0–20.6) compared to those without any source. Naming nurses as a source of information was not significantly associated with good knowledge of CC and CCS. Women whose source of information was nurses were 4.28 times more likely to have a positive attitude towards CC, and those who named other sources had 5.06 odds of having a positive attitude towards CC. Women whose source of information was nurses had 21.05 times higher odds of CCS (OR = 21,0, CI:10.4–42.3), and indicating another source of information was associated with 5.8 odds of CCS (OR = 5.8, CI:2.4–13.5). |

| Adewumi et al., 2019 [21] | Kenya | The study included women who participated in an outreach and education campaign (N = 120), women screened (N = 111) using HPV testing via self-collected vaginal swabs, women who received treatment (N = 283), and women who were non-adherent to treatment (N = 72) and CHVs (N = 18). | Rural | Qualitative | Community leaders and village elders were considered essential for information dissemination on CC in the community due to their understanding of the functionality of their communities and the best ways to disseminate information to them. Few women mentioned gender preferences, but generally, community leaders are men in the Kenyan context. Male partners were also seen as sources of information on HPV screening and treatment. | Screening: Most women reported that they did not need their partners’ permission to seek screening. Attitudes: Stigmatizing attitudes toward HPV was linked to its association with promiscuity, HIV, and infidelity. Knowledge: Good CC knowledge may improve access to services and chances of getting male partner support for HPV-based CCS. | Not applicable: qualitative study |

| Nyambe N et al., 2018 [22] | Zambia | Women (N = 40; 19 HIV+, 19 HIV−, 2- unknown); men (N = 19) ages 25–49; education level data not collected | Rural and urban | Qualitative | The main source of CC information in both rural men and women in the study was health facilities. Other sources cited by the rural sample were family and friends, literature and media, community outreach activities work, and school (for women only). At the urban site, a health facility was the main source of information for women, but work/school was the major source of information for men. Other sources were family, friends and family, media and workplace, and community outreach activities in the urban sample. In contrast to rural residents, urban residents cited a wider range of information sources mainly from institutionalized sources (media, schools, and workplaces), which are more likely to be more accurate. Rural respondents were more likely to get information from friends, family, and community outreach activities. | Screening: Approx. 52.5% (N = 21/40) of women had been screened. Among HIV+ women, a lack of time (linked to long travel time to clinics and long waiting times) was a major barrier to screening, and in HIV- women, being symptomatic was mentioned as a determinant of CCS. Attitudes: Not investigated Knowledge: Women were generally knowledgeable about the role of CCS in CC prevention. HIV+ women had more accurate knowledge about risk factors and other prevention strategies compared to HIV- women. Rural residents were more likely to be aware of CC risk factors related to hygiene (e.g., douching) and traditional practices (e.g., circumcision) compared to urban residents. | Not applicable: qualitative study |

| Osei EA et al., 2021 [23] | Ghana | Females ages 19–60 years: N = 15 (42.9%) had secondary education, N = 13 (37.1%) had attained tertiary education, and N = 7 (20%) had basic education (elementary); non-literate participants not included. | Rural | Qualitative exploratory | Participants who had screened cited nurses and doctors as their sources of information on CC, followed by social media (WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram), followed by reproductive health education girls club and women fellowship meetings. Social media was second on the list since the sample was mainly composed of young women between the ages of 19 and 29 years. Other participants learned about CC and CCS from relatives, schools, television, and friends | Screening: “Few” participants had been screened. Attitudes: Not investigated Knowledge: The majority of the participants had little knowledge of the CCS types, and most of those who knew about the types of CCS were health professionals (nurses, pharmacists). Few knew about CCS costs and how screening is performed. Most were knowledgeable about CCS centers. | |

| Ports KA et al., 2015 [24] | Malawi | Women (N = 30) ages 18–46 years: education levels ranged from illiterate to secondary school completion (median of 6 years). | Rural | Qualitative | Nurses and doctors were mentioned by over 50% of the women. Few women mentioned written sources (newspapers, posters). Several mentioned village meetings. Doctors, nurses, and health surveillance assistants were reported as the most credible sources of health information. In terms of CCS and HPV services, women stated that they would accept them only if health professionals recommended them. Others mentioned that they would encourage the village headman to organize a group meeting so that other women in the community could learn about CC and CCS (desire to be community health advocates). | Screening: There was an uptake in the majority of women who had been screened because they were experiencing persistent vaginal bleeding. Lack of information was a key barrier to CCS. Attitudes: More than half of women whose perceived personal risk was low had never been screened and did not use protective measures during sexual intercourse. Some women who had not screened reported that they will only seek screening if they have symptoms (which are associated with late-stage CC), rather than preventive screening. Knowledge: Women universally expressed the need and desire for more information (about CC symptoms, screening, HPV and HPV vaccination). | Not applicable: qualitative study |

| Compaore S et al., 2016 [25] | Burkina Faso (N = 346), Togo (n = 5), Chad (N = 1) | Women (N = 351) aged 18–72 years: 25.4% (89) with no formal education, 21.6% (N = 76) with primary education, 35.6% (N = 125) with high school education level, and 17.4% (N = 61) with college/university-level education. Approx. 56.4% of rural residents in the sample were unemployed. | Urban = 294 (83.8%), rural = 39 (11.1%), and semi-urban = 18 (5.1%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Health workers, relatives, friends | Screening: Approx. 54.7% of participants had never been screened. The main reason for not screening was a lack of awareness of CC and CCS, followed by not knowing where to get screened, fear of diagnosis with the disease, long distance to the hospital, and financial constraints. Urban residence (OR= 2.0; 95% CI: 1.19–3.25) and encouragement for screening by a healthcare worker (1.98; 95% CI: 1.06–3.69) were predictors of screening. Attitudes: Not reported Knowledge: Participants generally had a medium level of knowledge. There was higher knowledge among urban women (41.5%) compared to rural women (17.2%). | Women encouraged to have screening for medical reasons (advice from healthcare professionals or symptoms) were twice more likely to get screening (1.98; 95% CI: 1.06–3.69) than those with non-medical encouragement (relatives or friends’ advice). |

| Cunningham et al., 2015 [26] | Tanzania | Women (N = 575), ages 18–55 years. Education levels among rural residents: primary or less, 10.9% (33); completed secondary, 74.5% (225); college/university, 11.9% (36) and 1.7% (8). Education levels among urban residents: primary education or less, 5.5% (15); completed secondary, 56.1% (152); college/university, 32.5% (88) and 5.9% (16). | Rural =303 (52.7%) urban = 272 (47.3%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | The primary source of cervical cancer (CC) awareness was media (73%—radio; 22%—television; 13%—newspaper). Approx. 80% of rural women had heard about CC from the radio, followed by family/friend, church and healthcare providers, newspapers, and studies. Receiving information from church was more common among rural residents. The radio was also common among urban residents (64.3%), followed by television, family/friend, newspaper, studies, church, and healthcare. Only 13% of women had heard of CC from healthcare providers, and only 1% had heard from school. Churches, radio, and TV sources were significantly different between strata. | Screening: Approx. 4% rural and 9% urban had been screened. The largest barrier to screening was being unaware of the existence of preventive screening tests. Travel distance to healthcare facilities was a more frequently reported barrier in rural compared to urban women (27% versus 12%; p < 0.001). About 50% anticipated that the cost of screening or the travel costs would be prohibitive, and 25% stated that the opportunity cost of taking a leave of absence from work would be a barrier. Attitudes: Approx. 90% acceptability of screening among women who had never screened; more rural women were willing to travel more than 2 h to access screening (60% vs. 49%, p < 0.001). Rural women were more likely than urban women to believe that CC cannot be treated (63.1% versus 67.2%). Knowledge: Approx. 13% (n = 62) of the sample—17.9% (n = 40) of urban and 8.8% (n = 22) of rural—had adequate CC knowledge. | Not investigated |

| De Kubber et al., 2011 [27] | South Africa | Women (N = 532) ages 35–49 years; no other demographics provided | Rural | Descriptive cross-sectional | The main source of information was word of mouth from nurses in clinics (40%), followed by friends/relatives (44%); only 16% received information from the media (radio and television). | Screening: Uptake not studied. Attitudes: Approx. 90% were willing to screen. Among those unwilling, 23% and 25% mentioned fear of pain and test results, respectively. Knowledge: Approx. 60% and 74% of participants had heard about CC and Pap smear, respectively. Less than 50% knew the signs of CC. | Not investigated |

| Endalew DA et al., 2020 [28] | Ethiopia | Women of reproductive age (N = 268) ages 15–49 years: 18.5% were illiterate, 34 had primary education level (13%), 67 (25.8%), had secondary education, and 111 (42.7%) had college or above. | Rural and urban | Descriptive cross-sectional | Approx. 56.0% of respondents acquired information about cervical cancer screening from mass media, while 25.2% received information from family, friends, and neighbors; 11% from brochures and printed materials; and 7.8% from health workers. | Screening: Only 3.8% of respondents had ever been screened for cervical cancer. The majority of participants (N = 133 (53.2%) endorsed a lack of health education programs to promote cervical cancer screening as the main barrier to screening, and 11.6% stated long distance to screening facility. Approx. 30% thought that that screening would be too expensive, and 5.2% were afraid of a positive diagnosis for CC. Attitudes: Not studied Knowledge: Approx. 83.8% had heard about CC; 77% were unaware of its symptoms; between 0.4% and 9% knew about risk factors; and 98% did not know about CCS. | Women who had information about cervical cancer were 10 times more likely to have been screened for cervical cancer [(AOR = 10.2 (95%CI1.9–96.4)]. |

| Ezem BU, 2007 [29] | Nigeria | Women aged 20–65 years (N = 846). Approx. 630 (74.5%) had tertiary education, 124 (14.7%) had secondary education, and 24 did not indicate education level. | Rural town | Descriptive cross-sectional | Out of the 447 respondents who were aware of screening (52.8%), 140 received information from hospital sources, 138 (30.9%) got their information from friends, 94 (21%) from books or magazines, 40 from school, 13 from their husbands, 10 from television/radio, and 13 from other sources (e.g., those who had had cervical cancer). | Screening: only 7.1% (60) had ever been screened. The most common reasons for not screening were lack of awareness 390 (46.1%), did not see a need for it 106 (12.5%), fear of a bad result Approx. 98 (11.6%) did not know where screening can be performed; were not recommended by their doctor, 46 (5.4%); screening was too expensive, 46 (5.4%); and the rest endorsed other reasons or did not state 63 (7.4%). Attitudes: Not studied Knowledge: Approx. 52.8% of respondents were aware of CC. | Not investigated |

| Gebisa et al., 2022 [30] | Ethiopia | Women (N = 414) aged 18–49 years | Urban = 322 (77.8%), and rural = 92 (22.2%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Media (N = 149), health workers (N = 38), family/friends/neighbor (N = 60), religious leaders (N = 10), teachers (N = 20), written materials (N = 8) | Screening: Approx. 6.3% of women had been screened. Among those who had not been screened for cervical cancer, the most commonly reported reasons for not screening for cervical cancer were lack of information about the procedure (N = 187) and thinking they were healthy (N = 123). Attitudes: Approx. 46.1% had positive attitudes towards CCS; 26% agreed that precancerous CCS methods could be helpful in CC prevention. Knowledge: Approx. 69% had heard about CC, and 50.7% had good CC knowledge. | Not investigated |

| Isabirye A et al., 2020 [31] | Uganda | Women (N = 845) ages 25–49 years: only 57.6% had attained at least secondary education, 42.4% had attained some primary education, and 13.0% had no formal education. | Urban = 600 (71%), rural = 245 (29%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Cervical cancer screening information: radio (15%), health worker (42%), TV (16%), others (10%). Cervical cancer screening was higher among women whose main source of information about cervical cancer screening was health workers (41.5%). | Screening: Approx. 21% had been screened in their lifetime. Attitudes: Not investigated Knowledge: Approx. 58% had high CC and CCS knowledge. Women with high knowledge of CC and CCS were more likely to have screened (26.2%). | In univariate analysis, cervical cancer screening was significantly associated with the source of information (p < 0.001). |

| Kangmennaang J et al., 2015 [32] | Namibia | This analysis was focused on a sub-sample of women (N = 6542) aged 15–64 years who had heard about cervical cancer from a national sample; 357 (5.46%) had no formal education, 1198 (18.31%) had a primary education, 4301 (65.74%) had a secondary education level, and 686 10.49%) had tertiary education or higher. | Urban = 3756 (57.41%) Rural = 2786 (42.59%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Healthcare providers in health facilities, radio, television. | Screening: Only 38.92% (N = 2546) had ever been screened. Compared to urban residents, rural residents (OR = 0.68, p = 0.01) were less likely to report testing for cervical cancer. Attitudes: Not investigated Knowledge: Approx. 65.81% had heard of CC. | Having contact with health personnel in the last 12 months (OR = 1.35, p = 0.01) was also significantly associated with being screened for cervical cancer. Those who listen to the radio very often (OR =1.17, p = 0.10) and watched television frequently (OR = 1.26, p = 0.01) were more likely to report screening for cervical cancer. |

| Kasa et al., 2018 [33] | Ethiopia | Women (N = 735) ages 17–88 years: 111 (15.1%) were illiterate, and 248 (33.7%) had a diploma in their educational status | “Predominantly rural” | Descriptive cross-sectional | Sources of information about cervical cancer were family and friends (51.5%); health workers (19.8%); others (7.9%); media (16.5%) (type of media unspecified); brochures, posters, and other printed materials (4.3%). | Screening: Approx. 7.3% had been screened in their lifetime, most of whom had screened only once (83%); 68.5% of those screened endorsed self-initiation, while 31.5% were offered by health professionals. Reasons for not screening were lack of symptoms (45.4%) (N = 334), fear of the result (21.8%), not being informed (20.1%) (N = 160), and perception that that screening would be painful (5.3%). Attitudes: The majority had a negative attitude (63%) towards CCS; 48% were willing to screen; 36% thought that screening was not expensive; and 41% and 70% agreed that screening causes no harm, and any adult woman can acquire CC. Knowledge: Approx. 69.3% (N = 509) of participants had heard about cervical cancer; 142 (19.3%) had heard about CC screening. | Not investigated |

| Kimondo FC et al., 2021 [34] | Tanzania | Women (N = 297) ages 18–55: 4% (N = 12) had no formal education, 73.1% primary level education (N = 217), and 22.9% (N = 68) had secondary level education or more. Approx. 10.8% had health insurance. | Rural and urban regions | Descriptive cross-sectional | The major source of cervical cancer screening information was healthcare providers (80.1%), radio (42.8%), TV (23.2%), awareness campaigns (17.2%), relative/friends (9.1%), and print media (8.1%). Approx. 94.3% (n = 280) endorsed ownership of information technology devices (devices not specified in the study). | Screening: Approx. 50.2% (N = 149) had been screened for CC, and 64.4% (N = 96) of them were screened in the previous 12 months. Reasons for screening in the previous 12 months were mainly due to provider advice 88.6% (N = 132), followed by HIV status (22.8%), screening campaigns (18.8%), age (1.3%), and support from partners (0.7%). Among those unscreened, reasons for not screening were no symptoms (53.4%), uninformed about screening location (25%), unaware/busy (22.3%), delays in obtaining service (14.9%), fear of pain (11.5%), fear of results (8.8%), and expense (8.1%). Attitudes: The majority regarded screening as necessary (89%) and were willing to screen (79%). Overall, 67% had a positive attitude toward screening, and 71.4% were comfortable with screening by a healthcare provider of any gender. Knowledge: The majority had heard about CCS (90%) but only 21% knew the timing of CCS for women living with HIV. The majority were aware of CC signs and symptoms (71%) and ways to prevent it (53%). | Not investigated |

| Mruts KB & Gebremariam TB, 2018 [35] | Ethiopia | Female undergraduate students (N = 571) ages 17–38 years; illiterate participants not included. | Rural = 357; (62.5%) and urban = 214 (37.5%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Approx. 232 participants (40.5%) had heard about cervical cancer. The main sources of information were mass media (TV, radio), 134 (58%) and health institutions, 44 (19.0%). | Screening: Only 5 (0.9%) had ever been screened. The main reasons for not screening were lack of information, 276 (55.6%) and fear of being infected in 96 (19.4%) of participants. Attitudes: Approx. 33% considered themselves at risk for CC, 85% considered CC a severe disease, 65% and 75% believed its curable and preventable through screening, respectively. Knowledge: Approx. 41% had heard about CC, and 36% generally had good knowledge. | Using radio and TV as sources of information [AOR = 1.918 (95% CI: 1.223, 3.010)] and having information about STIs [AOR = 3.030 (95% CI: 1.665, 5.514) were independent predictors of good knowledge of CC. |

| Mukama T et al., 2017 [36] | Uganda | Women (N = 900) aged 25–49 years: 142 (15.8%) had no formal education, 530 (58.9%) completed primary, and 228 (25.3%) completed secondary education. | Rural = 610 (67.8%), semi-urban = 195 (21.7%), urban = 195 (10.5%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Radio was the main source of information about cervical cancer (N = 557; 70.2%), followed by health centers (N = 129; 15.1%), and friends/family members (N = 104; 13.1%). | Screening: Practices not reported Attitudes: The majority considered CC a severe disease (95%), curable if diagnosed early (78%), and symptomatic (83%). Most considered themselves at high risk for CC (76%) and believed that screening was important (94.4%). Knowledge: Approx. 99.8% (N = 898) of women had heard about CC, and 88.2% (N = 794) had heard about CC screening; 55% had high knowledge of CC and its risk factors. | Not investigated |

| Mwantake et al., 2022 [37] | Tanzania | Women living with HIV (WLHIV) (N = 297) aged 18–55 years: 229 (77.1%) had primary education or less, 68 (22.9%) had secondary education or above. Approx. 10.8% had health insurance. Illiterate individuals not included. | Rural districts and urban region | Descriptive cross-sectional | Healthcare providers (HCPs) (N = 238; 80.1%) and mass media (N = 145; 48.8%). Approx. 94.3% (N = 280) owned any form of technology. | Screening: Approx. 50.2% of the WLHIV had been screened for CC. Attitudes: Approx. 66.7% had a positive attitude towards CCS, and those who had a positive attitude towards screening (59%) had higher odds of CCS uptake compared to those with a negative attitude. Knowledge: About 72% had inadequate knowledge of CC signs and symptoms. | Women whose source of cervical cancer screening information was HCPs were 17.3 times more likely to have screened for CC compared to those who received information from other sources. |

| Ndejjo R et al., 2016 [38] | Uganda | Females (N = 900) aged 25–49 years: 672 (74.7%) had no/primary education, and 228 (25.3%) had post-primary education | Rural = 610 (67.8%) and semi-urban = 290 (32.2%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Health workers (48.8%); other sources not investigated | Screening: Only 43 (4.8%) (N = 20 rural residents and N = 23 urban/semi-urban residents) had ever been screened; 21 were screened because a health worker had requested, 16 self-initiated to know their status, and 17 did so after experiencing signs and symptoms associated with cervical cancer. Among participants who had not been screened, 416 (48.5%) stated that they were not aware, and 142 indicated health facility-related challenges (distance, costs, waiting times) and personal reasons (lack of time, fear of test outcomes, not being at risk, lack of time). Attitudes: Not investigated Knowledge: Knowing at least one method of CCS and someone who had ever been screened or diagnosed were positively associated with CCS uptake. | Recommendation for CC screening and knowing where CC screening was provided were independent predictors of CC screening ((p = 0.01) and (p = 0.04), respectively). Women who had been recommended for CC screening were 87 times more likely to have been screened. |

| Rimande-Joel R and Ekenedo GO, 2019 [39] | Nigeria | Women (N = 978) of childbearing age (15–49 years); no formal education (15.3%; N = 150), primary (N = 184), secondary (N = 369), tertiary (N = 275) | Urban = 440 (45%), rural = 254 (26%), semi-urban = 284 (29%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Nurses—during antenatal health education in government hospitals, health talks by political leaders (on diseases that affect women) | Screening: Approx. 45.2%, 25.6%, and 28.3% of women regularly, occasionally, or had never engaged in screening/prevention practices, respectively. Rural women had the poorest CCS and prevention practices. Attitudes: Albeit possessing appropriate knowledge, women generally had negative attitudes toward CC and its preventive measures (e.g., thought they were too young to contract CC, risk stigmatization if screened, believed screening is painful and showed a lack of faith in God). Knowledge: Rural residents had the least knowledge about CC. | Not investigated |

| Tadesse A et al., 2022 [40] | Ethiopia | Graduate female students who were registered for the academic year 2013/2014; 15–20 years (N = 568), >20 years (N = 99); year 1 (38.7%), year 2 (32.1%), year 4 (18.7%), and year 4 and above (10.5%); non-literate participants not included | Rural = 170 (25.5%) and urban = 497 (74.5%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Among women who heard about CC (60.6%), the most common source of information was news media (57.4%), and the least was religious leaders (1.7%). The second source was health workers (32.9%), followed by family/neighbor/friend (19.3%), teacher (17.1%), and brochure/other (16.6%). The majority of participants had poor knowledge scores (85.2%). | Screening: Only 2.2% had screened for CC in their lifetime. Lack of information was the most reported reason for not screening (42% (283), followed by lack of symptoms (28%), not yet decided (15%), feeling shy (5.5%), and high cost of screening (2.5%). Attitudes: Approx. 72% agreed that CC is fatal, 66% perceived that any woman can acquire CC, and 73% agreed that CCS helps in prevention. Knowledge: Approx. 61% had heard about CC, but only 15% had good CC knowledge. Those born in urban areas were twice more knowledgeable than those born in rural areas. | Not investigated |

| Tafere Y et al., 2021 [41] | Ethiopia | Women (N = 844) ≥18: 59.1% with formal education and 40.9% with no formal education | Rural = 514 (60.1%) and urban = 330 (39.1%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Approx. 66% of respondents had heard about CC mainly from health professionals (75.4%), and 10.6% used the media (radio, TV), and other sources not mentioned. | Screening: Uptake not reported. Lack of awareness and unfavorable attitudes towards screening impede CC prevention. Attitudes: Approx. 64% of respondents had a favorable attitude towards CC prevention measures, and 91% would agree to be screened if the test is free and creates no harm. Approx. 50% believed to be at risk, 48% agreed that CC is prevalent in Ethiopia, 62% agreed that it is non-communicable, 71% agreed that screening helps prevent CC, 65% perceived screening causes no harm, and 60% thought screening for CC is expensive. Knowledge: Approx. 75% had poor knowledge. Being a rural resident was negatively associated with knowledge of CC prevention measures (AOR = 0.21, 95%CI; 0.18, 0.34). | Not investigated |

| Tapera et al. 2019 [42] | Zimbabwe | Women (N = 277; N = 143 community sample and N = 134 hospital sample), aged ≥25: 71% had completed secondary education, 17% higher education, 13% primary; there were no illiterate participants in the sample. | Rural = 110 (39.7%) and urban = 167 (60.3%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | In the community sample (143), among those who had ever screened (N = 42), sources of CC information were radio (n = 30; 73%), TV (N = 8; 20%), health workers (0), and other (e.g., churches) (N = 3; 7%) | Screening: Approx. 29% (42) of healthy women had been screened; 86% of these were from urban areas, and 14% were from rural areas. The majority of those who had never been screened were <45 years old. More than half (52%) of women who had ever been screened were affiliated with Protestant and Pentecostal churches. Healthy women who had never visited doctors/health facilities in the last 6 months were less likely to screen. Attitudes: Not investigated Knowledge: The majority (74%) knew that CC is treatable. | Source of information was not associated with CC screening services after controlling for confounders (radio: OR = 1.18 (CI:0.02–58.95)); TV: OR = 5.48, CI (0.08–396). |

| Tekle T et al., 2020 [43] | Ethiopia | Women (N = 516) aged 30–49 years: 21.3% (n = 110) had no formal education, 20% (N = 103) had some primary school education, 24.4% (n = 126) had attended secondary school, and 34.3% (N = 177) had a diploma/degree. | Rural = 171 (33.1%) and urban = 345 (66.9%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Healthcare workers (52.5%), community, friends, mass media | Screening: Approx. 77.1% (398) had never screened for CC. Of those screened, 22.9% (118) had been screened only once; 52.5% were screened at the initiation of a health professional; (43.2%) were self-initiated; and the rest were initiated by community, mass media, or friends. Lack of information was the main reason for not screening and was mentioned by 83.7% of respondents. Other reasons were lack of a screening service (69.8%), long wait time (51.4%), lack of respect by health professionals (26%), expensive service cost (11.8%), and negative perception of procedure (10.5%). Only 15.2% (N = 26) of rural residents (N = 171) had screened, compared to 26.7% (n = 92) of urban residents (N = 345). Urban residents were 2 times more likely to have screened compared to rural residents 2.03 (1.25, 3.28). Attitudes: Approx. 46% had a favorable attitude toward CC and CCS. Knowledge: Approx. 43% had good CC and CCS knowledge. | Having sourced information about CC from a health professional was associated with good knowledge of CCS (AOR = 2.3, 95% CI: 1.27–4.17)); knowing someone who had CC was associated with screening for CC at least once (AOR = 2.47, 95% (1.37–4.44)). |

| Wakwoya EB et al., 2020 [44] | Ethiopia | Women aged 25–49 years (N = 1181): 33.7% were illiterate, 32.3% had primary education, 19.8% had completed some level of secondary education, and 14.1% had completed high school or more. | Urban = 821 (69.5%) and rural N = 360 (30.5%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Mass media was the main source of information, followed by health professionals and friends/neighbors in both categories of participants who had inadequate knowledge and those with adequate knowledge. | Screening: Uptake not reported Attitudes: Not investigated Knowledge: Approx. 49% had heard about CC, and 56% had adequate knowledge. | Having adequate cervical cancer knowledge was significantly associated with receiving information from healthcare providers (AOR: 2.72, 95% CI 1.69–4.37) compared to having mass media as the source of information. |

| Woldu BF et al., 2020 [45] | Ethiopia | Women (N = 237) ages 21–40 years: 32.1% with no formal education, 16.5% with primary education, 24.1% with secondary education, and 27.4% with a diploma or above | Rural = 105 (44.3%), urban, = 132 (55.7%) | Descriptive cross-sectional | Health professionals were the predominant sources of information (66.1%). Mass media 38.6% (n = 51) Printed materials 3.8% (N = 5) Health professionals 64.4% (N = 85) Family/friends 4.8% (N = 6) | Screening: Practice not investigated Attitude: Not investigated Knowledge: Only 56% had heard about CC; 52% had good knowledge of CC and CCS. Approx. 84.6% of women knew where screening services were offered. Urban residence compared to rural residence was associated with good knowledge. | Having a functional TV/radio was associated with adequate knowledge of cervical cancer in a bivariate analysis (p < 0.2) but not in a multivariate analysis. |

| Tiiti et al., 2022 [46] | South Africa | Women (n = 526) ≥18 years (mean age was 36.8 years); educational level not included | Rural = 12 (2.3%), semi-urban = 447 (85%), urban N = 63 (12%) | Analytic cross-sectional study | Approx. 7% (N = 37) of those who had screened (47.1%) reported that the screening had been recommended by a health worker. | Screening: Approx. 47.1% of the participants had been previously screened for CC using Papanicolaou (Pap) test. Attitudes: Not investigated Knowledge: Approx. 40%, 32%, 21%, and 6.3% had no knowledge, fair, good, and very good knowledge of HPV, respectively. Those previously screened had a higher likelihood of very good knowledge of HPV (60.6%). Only 19% currently mentioned causes/risk factors for CC. | Not investigated |

| Perng P et al., 2013 [47] | Tanzania | Women (N = 300) aged 25–49 years. Approx. 202 women were recruited from home, and 98 women were recruited during a 2-day free screening intervention. Approx. 4% had no formal education, 5% had some primary education, 74% completed primary or higher, and 22% were missing data. | Rural | Analytic cross-sectional | Radio; over 75% of the sample owned a radio. | Screened: Approx. 35% were screened during the study period. Attitudes: Those who were least averse to screening (23%) compared to the most averse (4.3%) were more likely to attend a screening service. Knowledge: CC risk factors (34%) and screening knowledge (18%) were positively associated with attending CCS. | Women who attended screening listened to the radio regularly (OR 24.76; 95% CI, 11.49–53.33, listened to the radio 1–3 times per week versus not at all) and were older (OR 4.29; 95% CI, 1.61–11.48, age 40–49 years versus 20–29 years) compared to women who did not. |

| Ayanto et al., 2022 [48] | Ethiopia | Women (N = 410 ages 30–49 years). Women who were eligible for screening and had been screened within the last 5 years and 28 of the control group (eligible for screening but not yet screened in the last 5 years) (case vs. control). No formal education N = 23 (11.2%), N = 27 (13.2%); primary education (1–8) N = 97 (47.1%), N = 112 (54.9%), secondary education (9–12) N = 47 (22.8%), N = 44 (21.6%), tertiary education (12+) N = 39 (18.9%), N = 21 (10.3%) | Rural = 287 (45.6%), urban =223 (54.4%) | Unmatched case-control | Among women who were informed about cervical cancer and CCS (N = 67.8%), sources of information were (case vs. control) health workers, 149 (73%) and 28 (13.6%); mass media, 43 (21.1%) and 39 (18.9%); social network, 8 (3.9) and 5 (2.4%); and Women’s Development Army, 3 (1.5%). | Screening: Urban residence was a significant predictor of screening utilization [AOR: 2.7, 95% CI: (1.56, 4.56)]. Attitudes: Approx. 48.5% of women who received CCS during the study period and within 5 years (cases) had favorable attitude towards CC and CCS compared to 47% (n = 96) of controls. Knowledge: Approx. 62% of the cases and 97% of controls had good CC knowledge. | Not investigated |

| First Author and Year | Study Design | Methodological Quality Criteria | Appraisal (Based on Reviewer 1 and 2 Consensus) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, No, Cannot Tell | Comments | |||

| Gafaranga et al., 2022 [3] | Qualitative study | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? 1.4. Is the interpretation of the results sufficiently substantiated by the data? 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | 1.1. Yes 1.2. Yes 1.3. Yes 1.4. Yes 1.5. Yes | N/A |

| Gatumo M et al., 2018 [11] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Jatho A et al., 2020 [13] | Concurrent mixed-methods design | 5.1. Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed-methods design to address the research question? 5.2. Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? 5.3. Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? 5.4. Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? 5.5. Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? | 5.1: Yes 5.2: Yes 5.3 Yes 5.4 No 5.5 Yes | Divergence and inconsistencies between qualitative and quantitative results were not reported. |

| Dozie et al., 2021 [14] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1: Yes 4.2. Yes 4.3. Yes 4.4. Yes 4.5. Yes | N/A |

| Ruddies F et al., 2020 [15] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Adewumi et al., 2019 [21] | Qualitative study | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? | 1.1. Yes 1.2. Yes 1.3 Yes 1.4 Yes 1.5 Yes | N/A |

| Nyambe N et al., 2018 [22] | Qualitative study | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by the data? 1.5. Is there coherence between the qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? | 1.1. Yes 1.2. Yes 1.3. Yes 1.4. Yes 1.5. Yes | N/A |

| Osei EA et al., 2021 [23] | Qualitative exploratory design | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by the data? 1.5. Is there coherence between the qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? | 1.1 Yes 1.2 Yes 1.3 Yes 1.4 Yes 1.5 Yes | N/A |

| Ports KA et al., 2015 [24] | Qualitative study | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? 1.4. Is the interpretation of the results sufficiently substantiated by the data? 1.5. Is there coherence between the qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? | 1.1 Yes 1.2 Yes 1.3 Yes 1.4 Yes 1.5 Yes | N/A |

| Compaore 2016 [25] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1: Yes 4.2: Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Cunningham et al., 2015 [26] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3.Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1: Yes 4.2: Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| De Kubber et al., 2011 [27] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Cannot tell 4.2 Cannot 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | The sampling strategy was unspecified; exclusion and inclusion criteria were unclear. |

| Endalew DA et al., 2020 [28] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Ezem BU, 2007 [29] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Cannot tell 4.5 Yes | 4.4 Cannot tell if nonresponse bias is low since the number of surveys distributed was not reported. |

| Gebisa et al., 2022 [30] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1: Yes 4.2: Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Isabirye A et al., 2020 [31] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Kangmennaang J et al., 2015 [32] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Kasa et al. 2018 [33] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Kimondo FC et al., 2021 [34] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1: Yes 4.2: Yes 4.3 No 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | The questionnaire was not pretested, and there was no mention of its validation processes and reliability tests. |

| Mruts KB and Ge-bremariam TB, 2018 [35] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Mukama T et al., 2017 [36] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1: Yes 4.2: Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Mwantake et al., 2022 [37] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Ndejjo R et al., 2016 [38] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1: Yes 4.2: Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Rimande-Joel R and Ekenedo GO, 2019 [39] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Tadesse A et al., 2022 [40] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Tafere Y et al., 2021 [41] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Tapera et al. 2019 [42] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Tekle T et al., 2020 [43] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 No 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | 4.3 The survey was adapted from a previous study but not pretested; no reports are available on its reliability in this study and the study that originally used the survey. |

| Wakwoya EB et al., 2020 [44] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Woldu BF et al., 2020 [45] | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | 4.1 Yes 4.2 Yes 4.3 Yes 4.4 Yes 4.5 Yes | N/A |

| Tiiti et al., 2022 [46] | Analytic cross-sectional study | 3.1. Are the participants representative of the target population? 3.2. Are the measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? 3.3. Are there complete outcome data? 3.4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? 3.5. During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? | 3.1 Yes 3.2 Yes 3.3 Yes 3.4 Yes 3.5 Yes | N/A |

| Perng P et al., 2013 [47] | Analytic cross-sectional study | 3.1. Are the participants representative of the target population? 3.2. Are the measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? 3.3. Are there complete outcome data? 3.4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? 3.5. During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? | 3.1 Yes 3.2 Yes 3.3 Yes 3.4 Yes 3.5 Yes | N/A |

| Ayanto et al., 2022 [48] | Unmatched case-control | 3.1. Are the participants representative of the target population? 3.2. Are the measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? 3.3. Are there complete outcomes of the data? 3.4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? 3.5. During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? | 3.1 Yes 3.2 Yes 3.3 Yes 3.4 Yes 3.5 Yes | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chepkorir, J.; Guillaume, D.; Lee, J.; Duroseau, B.; Xia, Z.; Wyche, S.; Anderson, J.; Han, H.-R. The Role of Health Information Sources on Cervical Cancer Literacy, Knowledge, Attitudes and Screening Practices in Sub-Saharan African Women: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070872

Chepkorir J, Guillaume D, Lee J, Duroseau B, Xia Z, Wyche S, Anderson J, Han H-R. The Role of Health Information Sources on Cervical Cancer Literacy, Knowledge, Attitudes and Screening Practices in Sub-Saharan African Women: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(7):872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070872

Chicago/Turabian StyleChepkorir, Joyline, Dominique Guillaume, Jennifer Lee, Brenice Duroseau, Zhixin Xia, Susan Wyche, Jean Anderson, and Hae-Ra Han. 2024. "The Role of Health Information Sources on Cervical Cancer Literacy, Knowledge, Attitudes and Screening Practices in Sub-Saharan African Women: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 7: 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070872

APA StyleChepkorir, J., Guillaume, D., Lee, J., Duroseau, B., Xia, Z., Wyche, S., Anderson, J., & Han, H.-R. (2024). The Role of Health Information Sources on Cervical Cancer Literacy, Knowledge, Attitudes and Screening Practices in Sub-Saharan African Women: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(7), 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070872