Social–Emotional Profiles of Preschool Children: An Investigation of Demographic Disparities and Intersectionality

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Young Children’s Social–Emotional Skills and Future Success

1.2. A Nuanced Approach to Examining Young Children’s Social–Emotional Skills

1.3. Intersectionality of Young Children’s Identity and Learning Experiences

1.4. The Current Study

- How can the social–emotional profiles of young children participating in HS programs be characterized?

- What is the predictive relationship between children’s demographic characteristics and their social–emotional profiles?

- How do children’s different demographic factors intersect in relation to their social–emotional development?

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source, Research Design, and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Social–Emotional Competence

2.2.2. Approaches to Learning

2.2.3. Social Cooperation

2.2.4. Problem Behaviors

2.2.5. Child Demographics

2.3. Analytical Plan

3. Results

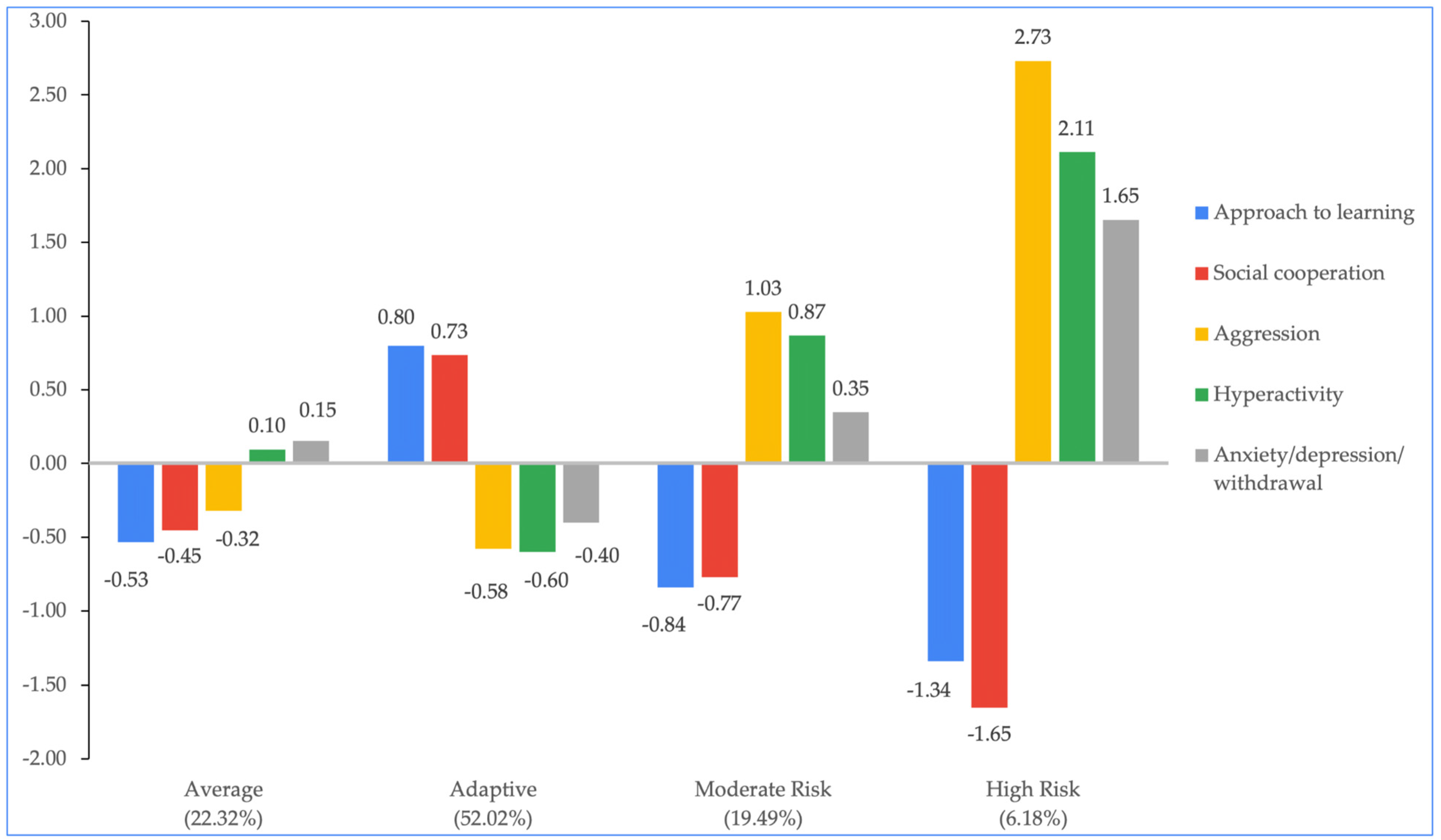

3.1. Heterogeneity of Social–Emotional Profiles

3.2. Demographic Disparities

3.3. Intersectionality

4. Discussion

4.1. Heterogeneity of Social–Emotional Profiles

4.2. Children’s Socio-Emotional Profiles are Varied by Demographics

4.3. Intersectionality of Race/Ethnicity and Other Demographics on Children’s Social–Emotional Profiles

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Administration for Children and Families. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. Head Start Family and Child Experiences Survey (FACES), United States, 2014–2017; Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [Distributor]: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.d.G.; Beja, M.J.; Candeias, A.; Santos, N. Emotion understanding, social competence and school achievement in children from primary school in Portugal. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela-Pino, I.; Alvariñas-Villaverde, M.; Pino-Juste, M. Socio-Emotional Skills as Predictors of Performance of Students: Differences by Gender. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.A.; Happold, C.A. The roots of school readiness in social and emotional development. In Set for Success: Building a Strong Foundation for School Readiness Based; The Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2002; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, K.C.; Richardson, C.G.; Gadermann, A.M.; Emerson, S.D.; Shoveller, J.; Guhn, M. Association of childhood social-emotional functioning profiles at school entry with early-onset mental health conditions. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e186694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.E.; Nicholson, J.M.; Walker, S.; Berthelsen, D. Early childhood profiles of sleep problems and self-regulation predict later school adjustment. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 86, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paschall, K.; Anderson Moore, K.; Pina, G.; Anderson, S. Comparing the national outcome measure of healthy and ready to learn with other well-being and school readiness measures. Child Trends 2020, 1, 1–19. Available online: https://cms.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/NOMMeasurement_ChildTrends_April2020.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Fuller, M.; Georgeson, J.; Healey, M.; Hurst, A.; Kelly, K.; Riddell, S.; Roberts, H.; Weedon, E. Improving Disabled Students’ Learning; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.A. Developing an indicator system to measure child well-being: Lessons learned over time. Child Indic. Res. 2020, 13, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; von Stauffenberg, C. Child characteristics and family processes that predict behavioral readiness for school. In Disparities in School Readiness: How Families Contribute to Transitions in School; Booth, A., Crouter, A.C., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 225–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam, S.G.; Parke, R.D. (Eds.) Exploring Family Relationships with Other Social Contexts; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brouzos, A.; Misailidi, P.; Hadjimattheou, A. Associations between emotional intelligence, socio-emotional adjustment, and academic achievement in childhood: The influence of age. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2014, 29, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamerslag, R.; Oostdam, R.; Tavecchio, L. Inside school readiness: The role of socioemotional and behavioral factors in relation to school, teachers, peers and academic outcome in kindergarten and first grade. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 26, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, M.M.; Acock, A.C.; Morrison, F.J. The impact of kindergarten learning-related skills on academic trajectories at the end of elementary school. Early Child. Res. Q. 2006, 21, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, C.; Manfra, L.; Hartman, S.; Bleiker, C.; Dineheart, L.; Winsler, A. School readiness skills at age four predict academic achievement through 5th grade. Early Child. Res. Q. 2021, 57, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimm-Kaufman, S.E.; Pianta, R.C.; Cox, M.J. Teachers’ judgments of problems in the transition to kindergarten. Early Child. Res. Q. 2000, 15, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, S. Changes in school readiness of America’s entering kindergarteners (1998–2010). In Kindergarten Transition and Readiness: Promoting Cognitive, Social-Emotional, and Self-Regulatory Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 111–138. [Google Scholar]

- Riemersma, I.; Van Santvoort, F.; Van Doesum, K.T.M.; Hosman, C.M.H.; Janssens, J.M.A.M.; Weeland, M.; Otten, R. Social-emotional problems of children with mild intellectual disabilities having parents with mental health concerns: A quantitative comparison study. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2022, 26, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.M.; Walker, S.P.; Fernald, L.C.; Andersen, C.T.; DiGirolamo, A.M.; Lu, C.; McCoy, D.C.; Fink, G.; Shawar, Y.R.; Shiffman, J.; et al. Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course. Lancet 2017, 389, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reardon, S.F. School segregation and racial academic achievement gaps. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saigal, S.; Doyle, L.W. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet 2008, 371, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grier, L.K. Character, social-emotional, and academic outcomes among underachieving elementary school students. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk (JESPAR) 2012, 17, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirk, M.; Grimm, R.; Furlong, M.J.; Nylund-Gibson, K.; Swami, S. The association of Latino children’s kindergarten school readiness profiles with Grade 2–5 literacy achievement trajectories. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 108, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonfeld, D.J.; Adams, R.E.; Fredstrom, B.K.; Weissberg, R.P.; Gilman, R.; Voyce, C.; Tomlin, R.; Speese-Linehan, D. Cluster-randomized trial demonstrating impact on academic achievement of elementary social-emotional learning. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2015, 30, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel-Walcutt, J.J.; Schatschneider, C.; Bowers, C. Social-emotional functioning of elementary-age deaf children: A profile analysis. Am. Ann. Deaf. 2011, 156, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogan, V.M.; Leung, R.C.; Safar, K.; Martinussen, R.; Smith, M.L.; Taylor, M.J. Longitudinal examination of everyday executive functioning in children with ASD: Relations with social, emotional, and behavioral functioning over time. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, S.A.; Bassett, H.; Mincic, M.; Kalb, S.; Way, E.; Wyatt, T.; Segal, Y. Social-emotional learning profiles of preschoolers’ early school success: A person-centered approach. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2012, 22, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McWayne, C.M.; Hahs-Vaughn, D.L.; Cheung, K.; Wright, L.E.G. National profiles of school readiness skills for Head Start children: An investigation of stability and change. Early Child. Res. Q. 2012, 27, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, H.; Justice, L.M.; Lin, T.J.; Purtell, K.M. One size doesn’t fit all: Profiles of isolated children in early childhood. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 80, 101397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskett, M.E.; Neal, S.C.; Norwalk, K.E. Exploring Variability in Social and Behavioral Adjustment Among Children in Head Start Experiencing Homelessness. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk (JESPAR) 2021, 26, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Kwon, K.A.; Guss, S.; Horm, D. Profiles of family engagement in home-and center-based Early Head Start programs: Associations with child outcomes and parenting skills. Early Child. Res. Q. 2020, 53, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentimonti, J.M.; Justice, L.M.; Kaderavek, J.N. School-readiness profiles of children with language impairment: Linkages to home and classroom experiences. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2014, 49, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassolie, T.; Bleiker, C.; Manfra, L.; Hartman, S.C.; Dinehart, L.H.; Winsler, A. How profiles of school readiness relate to grade 3 performance among low-income ethnically- and linguistically-diverse children. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2022, 26, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, A.J.; Ruderman, M.; Waterman, J.M.; Langley, A.K. Long-term effects of pre-adoptive risk on emotional and behavioral functioning in children adopted from foster care. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 130, 105031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Okada, K.; Hoshino, T.; Anme, T. Developmental trajectories of social skills during early childhood and links to parenting practices in a Japanese sample. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsler, A.; Tran, H.; Hartman, S.C.; Madigan, A.L.; Manfra, L.; Bleiker, C. School readiness gains made by ethnically diverse children in poverty attending center-based childcare and public school pre-kindergarten programs. Early Child. Res. Q. 2008, 23, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Iosif, A.M.; Young, G.S.; Bell, L.J.; Schwichtenberg, A.J.; Hutman, T.; Ozonoff, S. The dysregulation profile in preschoolers with and without a family history of autism spectrum disorder. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tourangeau, K.; Nord, C.; Lê, T.; Sorongon, A.G.; Hagedorn, M.C.; Daly, P.; Najarian, M. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 2010–11 (ECLS-K:2011), User’s Manual for the ECLS-K:2011 Kindergarten Data File and Electronic Codebook, Public Version (NCES 2015-074); U.S. Department of Education; National Center for Education Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Entwisle, D.R.; Alexander, K.L.; Pallas, A.M.; Cadigan, D. The emergent academic self-image of first graders: Its response to social structure. Child Dev. 1987, 58, 1190–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S.N.; Gresham, F.M.; Freeman, T.; McCloskey, G. Teacher and observer ratings of children’s social skills: Validation of the Social Skills Rating Scales. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 1988, 6, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.L.; Zill, N. Marital disruption, parent-child relationships, and behavior problems in children. J. Marriage Fam. 1986, 48, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.J. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, A.N.; Enders, C.K. An introduction to modern missing data analyses. J. Sch. Psychol. 2010, 48, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund, K.L.; Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B.O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.; Mendell, N.R.; Rubin, D.B. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika 2001, 88, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using M plus. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2014, 21, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyn, K.E. Latent Class Analysis and Finite Mixture Modeling; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rudasill, K.M. Child temperament, teacher-child interactions, and teacher-child relationships: A longitudinal investigation from first to third grade. Early Child. Res. Q. 2011, 26, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudasill, K.M.; Rimm-Kaufman, S.E.; Justice, L.M.; Pence, K. Temperament and language skills as predictors of teacher-child relationship quality in preschool. Early Educ. Dev. 2006, 17, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudasill, K.M.; Cheng, S.-L.; Xu, Y.; Xie, L.; Sealy, M.; Chen, C.-C. White Privilege in the Early Elementary Classroom: Implications for Students’ Achievement. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2024; submitted. [Google Scholar]

| Classes | Log Likelihood | AIC | BIC | SABIC | LMR | LMRR | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-class | −13,084.03 | 26,188.05 | 26,243.27 | 26,211.50 | x | x | x |

| 2-class | −11,210.47 | 22,452.94 | 22,541.29 | 22,490.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| 3-class | −10,514.44 | 21,072.87 | 21,194.35 | 21,124.46 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.90 |

| 4-class | −10,228.14 | 20,512.28 | 20,666.90 | 20,577.94 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.88 |

| 5-class | −10,099.56 | 20,267.11 | 20,454.86 | 20,346.84 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.87 |

| 6-class | No convergence | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Average vs. Adaptive | Moderate Risk vs. Adaptive | High Risk vs. Adaptive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Exp (β) | (95% Confidence Interval) | β | Exp (β) | (95% Confidence Interval) | β | Exp (β) | (95% Confidence Interval) | |

| Male | 0.61 | 1.84 ** | (1.40–2.41) | 1.19 | 3.29 ** | (2.41–4.51) | 1.53 | 4.62 ** | (2.88–7.42) |

| Black | 0.72 | 2.06 ** | (1.35–3.16) | 0.54 | 1.72 * | (1.06–2.80) | 0.99 | 2.69 * | (1.19–6.09) |

| Hispanic | −0.07 | 0.93 | (0.63–1.39) | −0.68 | 0.51 * | (0.30–0.87) | −0.61 | 0.54 | (0.24–1.23) |

| Other | 0.05 | 1.05 | (0.64–1.74) | −0.72 | 0.49 + | (0.22–1.05) | 0.36 | 1.44 | (0.77–2.67) |

| Age | −0.06 | 0.94 ** | (0.92–0.97) | −0.06 | 0.94 ** | (0.92–0.97) | −0.06 | 0.94 ** | (0.90–0.98) |

| Disabilities | 0.32 | 1.37 | (0.82–2.29) | 0.51 | 1.66 * | (1.04–2.63) | 1.51 | 4.55 ** | (2.05–10.09) |

| Poverty | 0.11 | 1.12 | (0.77–1.63) | 0.15 | 1.16 | (0.86–1.56) | 0.34 | 1.41 | (0.72–2.75) |

| Average vs. Adaptive | Moderate Risk vs. Adaptive | High Risk vs. Adaptive | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 β | Model 2 β | Model 3 β | Model 4 β | Model 1 β | Model 2 β | Model 3 β | Model 4 β | Model 1 β | Model 2 β | Model 3 β | Model 4 β | |

| Male | 0.48 | 0.61 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.99 ** | 1.21 ** | 1.19 ** | 1.19 ** | 1.69 ** | 1.54 ** | 1.52 ** | 1.53 ** |

| Black | 0.54 + | 0.52 | 0.77 ** | 0.70 | 0.36 | −2.21 | 0.43 + | 0.69 | 1.28 * | −0.64 | 0.72 | 0.89 |

| Hispanic | −0.08 | 0.61 | −0.07 | 0.16 | −0.91 + | −1.99 * | −0.92 ** | −0.77 ** | −0.98 | −2.07 | −0.74 | −0.20 |

| Other | −0.01 | −0.47 | 0.12 | 0.28 | −0.68 | −6.80 ** | −0.96 * | −0.76 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.16 | 0.62 |

| Age | −0.06 ** | −0.05 + | −0.06 ** | −0.06 ** | −0.06 ** | −0.09 * | −0.06 ** | −0.06 ** | −0.06 ** | −0.08 * | −0.06 ** | −0.06 ** |

| Disabilities | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.51 * | 0.52 | −0.16 | 0.52 * | 1.52 ** | 1.53 ** | 0.98 | 1.51 ** |

| Poverty | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.53 |

| Bla*Male | 0.39 | 0.36 | −0.30 | |||||||||

| His*Male | 0.06 | 0.38 | 0.48 | |||||||||

| Oth*Male | 0.13 | −0.06 | −0.87 | |||||||||

| Bla*Age | 0.00 | 0.06* | 0.03 | |||||||||

| His*Age | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |||||||||

| Oth*Age | 0.01 | 0.12* | −0.02 | |||||||||

| Bla*Disab | −0.47 | 0.49 | 0.81 | |||||||||

| His*Disab | 0.21 | 1.45 + | 0.65 | |||||||||

| Oth*Disab | −0.46 | 1.21 | 0.65 | |||||||||

| Bla*Pov | 0.01 | −0.22 | 0.08 | |||||||||

| His* Pov | −0.34 | 0.11 | −0.59 | |||||||||

| Oth*Pov | −0.37 | 0.07 | −0.42 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, C.-C.; Xu, Y.; LoCasale-Crouch, J.; Xia, Y.; Rudasill, K.; Xie, L.; Johansen, K.; Joy, J.; Askue-Collins, J. Social–Emotional Profiles of Preschool Children: An Investigation of Demographic Disparities and Intersectionality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081100

Chen C-C, Xu Y, LoCasale-Crouch J, Xia Y, Rudasill K, Xie L, Johansen K, Joy J, Askue-Collins J. Social–Emotional Profiles of Preschool Children: An Investigation of Demographic Disparities and Intersectionality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(8):1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081100

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Chin-Chih, Yaoying Xu, Jennifer LoCasale-Crouch, Yuyan Xia, Kathleen Rudasill, Lindai Xie, Karli Johansen, Jeen Joy, and Jennifer Askue-Collins. 2024. "Social–Emotional Profiles of Preschool Children: An Investigation of Demographic Disparities and Intersectionality" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 8: 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081100

APA StyleChen, C.-C., Xu, Y., LoCasale-Crouch, J., Xia, Y., Rudasill, K., Xie, L., Johansen, K., Joy, J., & Askue-Collins, J. (2024). Social–Emotional Profiles of Preschool Children: An Investigation of Demographic Disparities and Intersectionality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(8), 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081100