Abstract

This review aims to analyze the evidence related to violence perpetrated against transgender individuals in health services based on their narratives. This is a systematic literature review of qualitative studies. A search was carried out in the Scopus, Web of Science, Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences (LILACS), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), EMBASE, and MEDLINE databases using the descriptors “transgender people”, “violence”, and “health services”. The eligibility criteria included original qualitative articles addressing the research question, with fully available text, reporting violence specifically by health workers, involving trans individuals aged 18 and above, and published in Portuguese, English, or Spanish. In addition, studies were included that reported experiences of violence suffered by the trans population, through their narratives, in health services. A total of 3477 studies were found, of which 25 were included for analysis. The results highlighted situations such as refusal of service; resistance to the use of social names and pronouns; barriers to accessing health services; discrimination and stigma; insensitivity of health workers; lack of specialized care and professional preparedness; and a system focused on binarism. The analysis of the studies listed in this review highlights the multiple facets of institutional violence faced by the transgender population in health services. It is evident that the forms of violence often interlink and reinforce each other, creating a hostile environment for the transgender population in health services. Thus, there is an urgent need to create strategies that ensure access to dignified and respectful care for all individuals, regardless of their gender identity.

1. Introduction

Transgender (trans) is an umbrella term used to refer to transsexuals, transvestites, non-binary, and other possibilities, who do not identify with the binary gender classification (male or female) and heterocisnormativity (which regards identities, genders, and bodies as products regulated by a given society), both associated with the biological anatomical sex at birth (male, female, or intersex) [1,2,3].

Due to their “deviant” behavior and unique characteristics of gender expression, which break away from behaviors marked as “standard”, the trans population is highly marginalized in various spaces [2,3,4], resulting in their exclusion and social erasure. Consequently, they are exposed to stressors, mainly involving family and community violence, which increases stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, post-traumatic disorders, substance abuse, and suicide cases [4,5,6].

It is known that trans people are frequently exposed to verbal, psychological, and physical violence, and this situation is considered natural in the collective imagination. For these reasons, institutional violence can be observed in various spaces, including health services [7].

Institutional violence can be seen as a set of deleterious situations practiced in service-providing institutions by agents who should meet the demands and protect users but fail to do so, either by omission or commission [8]. It is, therefore, a set of systematic abuses or violations committed by institutions against people or groups, based on power relations and motivated by inequalities involving socioeconomic conditions, ethnicity, age, religion, and gender, among others [9].

The literature considers that institutional violence arises individually, therewith, from the person who practices it. The consistency and high distribution of episodes characterize it as institutional [10].

In health services, the trans population tends to face hostility involving denial of care [11,12,13], verbal harassment, stigma, discrimination [14,15,16,17,18], denial of equal treatment [16,18,19,20], and non-acceptance of the use of social names and appropriate pronouns by staff members [16,17,21,22,23,24].

Despite the significant advances through demands and constant struggles (strikes, marches, lawsuits, court decisions/rulings) achieved by the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, Queer/Questioning, Asexual/Aromantic, Pansexual, Non-binary, and others (LGBTQIAPN+) population worldwide, the transgender population still faces alarming peculiarities. The extremely reduced life expectancy (about 35 years) and episodes of murders motivated by transphobia represent a serious global public health issue [25,26].

Thus, it is assumed that disparities in access to health services directly impact the health conditions of the trans population. This situation can influence the quality (in this case, the lack thereof) and life expectancy of the trans population [17], being considered a grave form of violence against this population. This study aims to analyze the evidence related to institutional violence perpetrated against transgender individuals in health services based on their narratives.

2. Materials and Methods

The data collection started after the construction, registration, and publication of the protocol in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). The registration number is CRD42024524059.

This is a systematic review of qualitative studies based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [27] manual for evidence synthesis of systematic reviews of qualitative research and aligned with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [28].

Qualitative research is understood from a complex and interconnected family of terms, concepts, and hypotheses [29]. This type of study aims to explore a phenomenon of investigation (in this case, institutional violence suffered by the trans population in health services) without focusing on statistical quantification and generalization [30]. Moreover, it allows for a more refined understanding of a phenomenon based on the perceptions of subjects, considering their most subjective aspects.

The following steps were defined for this study: identifying the theme and guiding question, establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria, defining the information to be extracted from the selected studies, evaluating the studies included in the systematic review, interpreting results, and synthesizing knowledge.

The research question was defined based on the PICo strategy, where P is the population (transgender persons); I is the phenomenon of interest (violence); and Co is the context (health service). The following question was formulated: What is the scientific evidence related to institutional violence perpetrated against transgender individuals in health services?

The eligibility criteria included original qualitative articles addressing the research question, with full-text availability, reporting violence specifically by health workers, involving trans individuals aged 18 and above, and published in Portuguese, English, or Spanish. In addition, studies were included that reported experiences of violence suffered by the trans population, through their narratives, in health services. Duplicated studies, gray literature texts, and those involving populations and settings divergent from the established eligibility criteria were excluded. Studies that discussed violence against the broader LGBTQIAPN+ population without specific details on the violence suffered by the trans population and their particularities were also excluded.

The term “health workers” was used to encompass individuals holding various positions, including health professionals and other staff, regardless of hierarchical and educational levels [31].

The search for articles was conducted in March 2024 using the DeCS/MeSH descriptors “transgender persons”, “violence”, and “health services” in their respective word banks. Additionally, these descriptors were submitted to PubMed and Web of Science databases to expand the number of synonyms. Based on the synonyms, titles, abstracts, and descriptors of the found articles, the terms for this study were defined (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptors found from automatic and manual searches.

Based on these defined descriptors, a new search was conducted in the Scopus, Web of Science, Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences (LILACS), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), EMBASE, and MEDLINE databases using the Boolean operators AND and OR, adapted to each database according to their specificities (Table 2). The search strategy was created to be as broad as possible, reducing the possibility of missing relevant articles for this review. It should be noted that all the searches were carried out on 20 March 2024.

Table 2.

Search strategy adapted for database searches.

The data, after being gathered, were exported to the Rayyan QCRI platform. This platform assists in the process of excluding duplicate studies, as well as in the subsequent reading of titles and abstracts. This first reading was carried out by two independent researchers. A third evaluator was invited to help make decisions (inclusion or exclusion) in cases of disagreement or doubt between the first two. Thus, the studies selected at this stage were subjected to full-text reading, allowing for an analysis of their relevance concerning their inclusion in the review.

Data extraction was carried out using an adapted version of the Lockwood et al. form [32], which included the following variables: author; year and journal of publication; phenomenon of interest (objective); method (study location, participants, data analysis); and main results. The critical reading process was carried out using JBI’s [27] critical evaluation tools. The methodological quality assessment of the studies included in this review was carried out using a checklist for qualitative research evaluation proposed by JBI [27].

3. Results

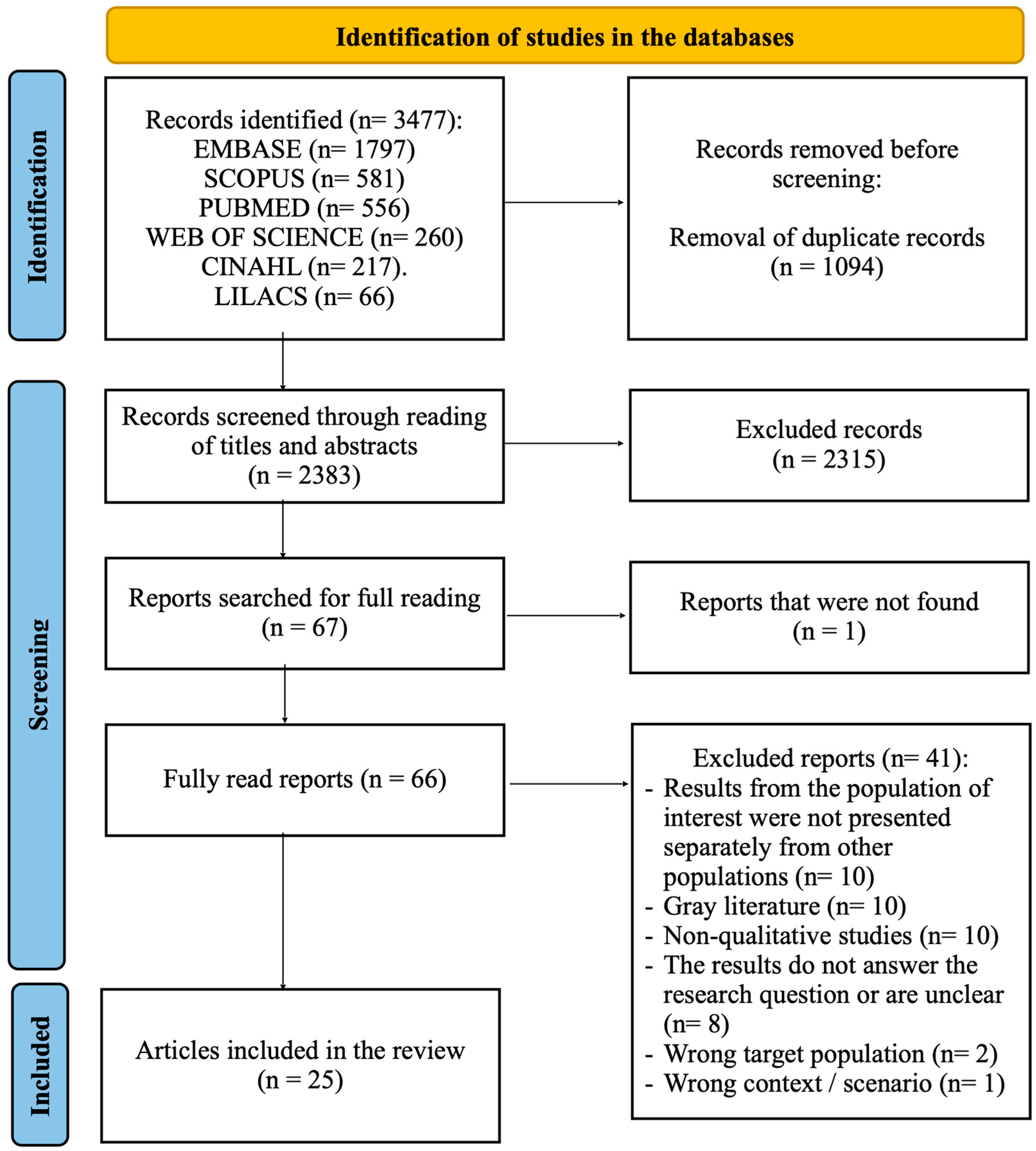

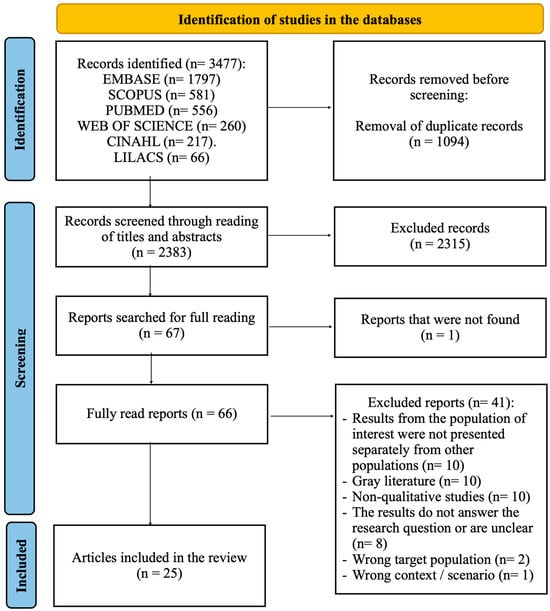

The detailed selection of studies can be viewed in the flowchart (Figure 1). A total of 3477 studies were found in the databases. Initially, 1094 were excluded for being duplicate texts. Of the remaining 2383, 2315 were excluded after reading the title and abstract. Then, the remaining texts were read in full (67 studies, as one was not available). Finally, 42 were rejected after a thorough analysis based on the other eligibility criteria. Thus, 25 [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] studies were used to compose this review (Table 3).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart. Source: created from the model by Page et al. [28].

Table 3.

Information and synthesis of the main results of studies selected for systematic review.

The publication of these 25 articles occurred between 2013 and 2024, with two in 2013 [33,34], two in 2015 [35,36], one in 2016 [37], two in 2018 [38,39], four in 2019 [40,41,42,43], three in 2020 [44,45,46], one in 2021 [47], five in 2022 [48,49,50,51,52], four in 2023 [53,54,55,56], and one in 2024 [57].

Regarding the place of publication, the articles come from 10 countries: Brazil (6 studies) [36,40,45,48,53,54], United States of America (5 studies) [33,34,39,42,52] Canada (4 studies) [35,37,46,56], Uganda (3 studies) [41,51,55], Colombia (2 studies) [38,44], Peru (1 study) [47], Spain (1 study) [49], Nigeria (1 study) [50], India (1 study) [43], and Turkey (1 study) [57].

Concerning the methodological quality of the studies (Table 4), all showed congruence between the research methodology and the research question or objective [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57], between the research methodology and the methods used to collect the data [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57], between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of the data [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57], as well as between the research methodology and the interpretation of the results [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. Similarly, all studies adequately represented the participants and their voices [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] and brought conclusions aligned with the data collection and analysis [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57].

Table 4.

Methodological quality of articles included in the systematic review.

The ethical aspects were clear, evident, and appropriate in 24 studies [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. Thus, only one study did not clarify whether it was submitted to a Research Ethics Committee or a similar body in the location where it was conducted [57]. Regarding the statement that locates the researcher culturally or theoretically in the study, 16 articles evidenced that there was this location [33,35,38,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,49,50,52,53,56,57], 8 did not make this aspect clear [34,36,39,47,48,51,54,55], and 1 did not show it [37]. The influence of the researcher was perceived in 8 texts [35,42,43,44,45,46,56,57]. In the others 17 texts [33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55], it was not clear whether there was this type of influence or not.

4. Discussion

The violence suffered by the trans population proved to be substantially diversified. Thus, discussion blocks were created based on the participants’ experiences and the authors’ analysis of the studies. This way, it was possible to identify seven blocks, namely: 1. refusal of care; 2. resistance to the use of social name and pronoun; 3. barriers to accessing health services; 4. discrimination and stigma; 5. insensitivity of health workers; 6. lack of specialized care and professional unpreparedness; and 7. technological limitations relating to the binary-focused system. It is worth noting that although the blocks are presented separately, the forms of violence coexist and are interconnected.

Although all the factors represent a potential barrier to accessing health services, we chose to create blocks based on the information that emerged from the studies included in this review. We know that various situations of violence can result in a barrier to access. However, unfortunately, many trans people have to ignore the way they are treated in order to receive the minimum health care.

4.1. Refusal of Care

Refusal of care was an evident phenomenon in five studies [34,41,47,51,55]. According to the target population’s reports, the motivations for this refusal were strongly related to their gender identity [47,51] and their way of dressing [41]. In the latter case, a trans woman noted that the professional did not provide quality care if she was wearing a dress. The omission of health workers in providing care was also observed in three studies [34,42,55].

In the study by Kosenko et al. [34], a trans person reported being asked to leave the health facility by the professional who was providing care after expressing a desire to undergo the gender affirmation process (commonly referred to as “transition” surgery), clearly indicating a behavior change associated with gender issues.

According to Mello et al. [58], trans people are the individuals who face the most difficulty when seeking health services. These recurring episodes of violence and refusal are motivated by both transphobia and discrimination associated with various social and cultural factors.

4.2. Resistance to the Use of Social Names and Pronouns

Resistance to the use of social names and pronouns was one of the most frequently emerging themes in the studies. Of the 25 studies included in this review, 14 addressed this issue [34,36,38,39,40,42,44,45,46,48,49,50,54,56].

In one study, a participant claimed that health workers only called him by his registered name, and that things only progressed, in small steps, after he changed his identity documents [48].

Other studies [45,49] show that even after requesting the use of the social name and appropriate pronoun, health workers insisted on using the registered name, disrespecting the individual’s identity [36,44].

According to Teixeira [59], assigning a new name is part of the identity construction process for trans people, which tends to be accompanied by physical and behavioral changes (although these changes are not a rule). Furthermore, the author states that this name carries multiple meanings and significances. Thus, not using the social name is a serious disrespect to the person [42,54,56] and is recurrently seen by the trans population as an unjustifiable lack of sensitivity [39,50].

4.3. Barriers to Accessing Health Services

Barriers to accessing health services are also a substantially relevant theme. In seven studies [33,37,38,41,44,50,56], the difficulties faced by the trans population in seeking health care were perceived.

In the trans population’s view, there is a lack of specialized places for their care [56]. Furthermore, many barriers stem from gender-based violence [37]. Similarly, users’ reports of not feeling comfortable discussing their gender [33,50] are common and represent a significant challenge.

When asked about the barriers, some users reported that the obstacles are created by the workers’ attitudes [41]. This allegation aligns with Rosa et al. [60], who state that a considerable portion of workers has adopted a negative stance toward trans people, creating a hostile environment and providing discriminatory and prejudiced care.

Barriers to accessing sexual and reproductive health services are also addressed in one of the studies [44]. Winter et al. [4] state that neglecting the needs of transgender women, for example, can contribute to the disproportionate risk of HIV in this group.

Lack of health insurance [33] and financial conditions [52] were also associated with difficulty accessing services, resulting in self-care and self-medication in many cases [33]. It is known that the trans population constantly deals with difficulties associated with the job market (lack of employment), which also results in low availability of resources to pay for their health [1].

It is noteworthy that only one study [40] found that the difficulty in access was associated with various factors not necessarily related to discrimination and transphobia, as they were characterized as “commonly faced” problems by users. However, the same study showed that discrimination prevents or hinders trans/transvestite people from accessing health services. This corroborates other investigations [36,49,51], as they indicate that how users are treated influences their return to consultations and the continuity of treatments. Trans people often avoid services, even in more severe health cases.

4.4. Discrimination and Stigma

Discrimination and stigma were also some of the most frequently mentioned themes in the studies. Out of the total analyzed, 14 addressed this type of violence [36,38,39,41,47,48,49,50,51,52,54,55,56,57].

Anticipated discrimination [56] and stigmatizing care [49] were strongly present in the studies, showing that healthcare workers often prejudge the health situations of transgender people, assuming they necessarily have sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [36,38,48,57] or that they are drug users and/or users of other illicit substances [54]. As a result, STI tests are conducted with judgmental attitudes [50], corroborating the findings of the study by Shihadeh, Pessoa, and Silva [15].

Discriminatory positions and questioning by team members [39,41,47,51,52,55] and workers from other areas [38] (such as security guards of the institutions), as well as verbal abuse and discriminatory language [38], also emerged in the analyzed articles.

Seven studies [34,38,42,49,53,56,57] documented extreme negligence and violations against transgender individuals. These situations are motivated by cultural and especially religious beliefs, revealing prejudice and religious discourses. For instance, there are reports of workers using religious books to confront the patient’s gender identity [55] and/or to reaffirm the biological factor as predominant [42]. It is known that religious discourses constitute a significant challenge, as they consider transgender people as potentially sinful [16]. These experiences, combined with other factors, lead the population to avoid returning to healthcare services [53].

Some studies also highlighted the disdain some healthcare workers have for transgender individuals. Statements like “if I had known you were trans, I wouldn’t have touched you” emerged during health appointments [57]. The excessive use of protective gear for simple procedures in these situations reveals, from the user’s perspective, considerable repulsion by the worker [49].

The absence of care or substandard care was also noted. Procedures such as suturing a wound without anesthesia [34] and focusing a medical history on gender rather than health condition [42] are present in the reports.

Due to fear of discrimination and especially of being ridiculed, many transgender people provide incomplete and/or incorrect health information to healthcare workers [55]. Moreover, due to fear of discrimination in healthcare services, transgender people have abandoned important follow-ups and treatments, worsening the phenomenon of exclusion from healthcare access [61].

It is known that transgender people prefer to seek alternative or parallel care methods [4,39]. Rocon et al. [16] report that transgender women, for example, choose to frequent “houses of worship”, where they find respect and dignity.

The way marginalized individuals are treated shapes their self-perception and how they interpret their contexts [38]. It is thus clear that discrimination is still underestimated, even though it is considered a key point for exclusion and denial of access to healthcare services [16].

4.5. Insensitivity of Healthcare Workers

The target population, through their statements and the authors’ analyses of the articles included in this review, mentioned episodes of insensitivity by healthcare workers, which were evident in nine publications [33,34,41,43,46,49,50,54,55].

Differentiated and discriminatory treatments, such as the absence of physical touch, lack or delay in care time [55], and changes in behavior upon learning of the patient’s transgender identity [33,34,41,43,46], were observed. Two studies [34,38] discussed the imposition of forced treatments due to hormone administration against the will of the transgender person (but with the “consent” of the family) and involuntary psychiatric care, highlighting the erasure of the individual’s desires by healthcare workers and other individuals.

For the transgender population, lack of sensitivity [33,50,54], strange looks, and disrespectful comments [48] are recurrent situations. These findings align with Winter et al.’s study [4], showing that healthcare workers are often seen as unsympathetic or hostile to the health needs of transgender people, providing inadequate care.

Almeida and Murta [62] emphasize the need to invest in the sensitization of healthcare workers, including other users of healthcare units. The authors, based on the Brazilian Ministry of Health’s Ordinance 457/2008, which regulates the transsexualizing process within the Unified Health System (the national health system), highlight the need for discrimination-free care, focusing on respect for differences and human dignity.

4.6. Lack of Confidence in Healthcare Services

Lack of specialized care and professional unpreparedness emerged in 11 studies [35,36,38,39,42,45,47,48,51,52,54].

The selected studies show that such situations result from healthcare workers’ lack of knowledge regarding transgender care [35,36,39,42], lack of information [38,47,48], and the absence of trans-specific and gender-affirming services [47,51,54].

Lobo et al.’s [53] study reveals that the absence of services considering the unique needs of the transgender population reduced the confidence level of the investigated transgender men and transmasculine individuals.

In one of the selected studies [49], a transgender person mentioned that they believed healthcare professionals do not have contact with trans issues during their training. This confirms studies [24,63] showing that professionals are generally unprepared to care for transgender people because they have not acquired or improved the necessary competencies to deal with this population during their training. Thus, constant training and capacity building of the entire healthcare team are necessary [39].

It is worth noting that two studies [39,56] showed that some healthcare workers’ attitudes made the transgender population feel more welcomed. These situations occurred when workers displayed, for example, flags and stickers related to the transgender population in a counseling office.

Lo and Horton [64] state that the lack of information about transgender healthcare is due to insufficient awareness and lack of acceptance of these individuals by healthcare workers. Trindade9 adds that institutional violence against transgender people is expressed, among other ways, by not hiring qualified and interested personnel to welcome the transgender population.

4.7. Technological Limitations Relating to the Binary-Focused System

Although less frequent, this section is also significantly relevant. Three studies [44,52,56] showed the challenges associated with transgender care. In this case, they report workers focused on a binary classification of sex and gender, as well as equally exclusive management systems.

Two studies reported transgender users’ complaints about limitations in health service documents and forms. According to these users, there is often no space to fill in gender identity in institutional documents [52,56].

Similarly, one study [44] shows that, in transgender users’ view, healthcare workers do not know how to deal with them because they have a limited view of the universe of sexual and gender expression possibilities. For these users, it is as if healthcare workers only see being male or being female.

It is known that discriminatory practices are based on gender and stereotypes driven by heteronormativity, besides focusing on the biomedical model [16]. Therefore, it is necessary to legitimize care based on a humanistic model centered on the patient from a holistic and comprehensive perspective [49].

Based on the results of this study, it is recommended to develop primary investigative studies, constantly train and capacitate healthcare workers, and create and/or improve clinical programs based on harm reduction, given the specificities of this population and the associated social determinants of health.

The authors of this study understand that the countries cited in the studies included in the review (Canada, Brazil, Uganda, Colombia, Turkey, USA, Spain, Nigeria, India, and Peru) have different health system organizations, and that this tends to imply different access to health services. However, no complementary analyses have been carried out to show these differences. We therefore recommend that future studies analyze and evaluate these variables.

This study included the transgender population as a whole, without considering whether they are transgender men, transgender women, or non-binary transgender people. Moreover, the specific contexts of each population, influenced by the culture and socioeconomic issues of each country and region, were not studied. The search was broad in the selected databases, allowing for a significant number of studies. For these reasons, manual searches were not conducted, nor were documents from gray literature included. Thus, future research is suggested to investigate the mentioned variables (intrinsic and extrinsic factors), broaden the scope of review, as well as conduct multicenter and field studies.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the studies included in this review highlights the multiple facets of institutional violence faced by the transgender population in healthcare services. Furthermore, it is evident that forms of violence often interconnect and reinforce each other, creating a hostile environment for the transgender population in healthcare services. Therefore, the urgency of creating strategies that ensure access to dignified and respectful care for all people, regardless of their gender identity, is highlighted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.d.C.L. and P.F.P.; methodology, G.d.C.L. and P.F.P.; formal analysis, G.d.C.L., P.F.P., J.N.d.B.S.J., Q.R.F. and J.G.d.A.B.; investigation, G.d.C.L., J.N.d.B.S.J. and Q.R.F.; data curation, G.d.C.L., J.N.d.B.S.J. and Q.R.F.; writing—original draft preparation, G.d.C.L., P.F.P., J.N.d.B.S.J., Q.R.F. and J.G.d.A.B.; writing—review and editing, G.d.C.L., P.F.P., J.N.d.B.S.J., Q.R.F. and J.G.d.A.B.; visualization, G.d.C.L., P.F.P., J.N.d.B.S.J., Q.R.F. and J.G.d.A.B.; supervision, P.F.P.; project administration, G.d.C.L. and P.F.P.; funding acquisition, P.F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001 (PROGRAMA PROEX—Auxílio no. 1603/2024—Process number: 88881.973889/2024-01) and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico and Tecnológico—Brazil (CNPq) (Research productivity scholarship—Process number: 308996/2020-8).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hernandez-Valles, J.; Arredondo-Lopez, A. Barreras de acceso a los servicios de salud en la comunidad transgénero y transexual. Horiz. Sanit. 2020, 19, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.L.; Lopes, R.O.P.; Bitencourt, G.R.; Bossato, H.R.; Brandão, M.A.G.; Ferreira, M.A. Identidade social da pessoa transgěnero: Análise do conceito e proposição do diagnόstico de enfermagem. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20200070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.K.M.; Silva, A.L.M.A.; Coelho, A.A.; Martiniano, C.S. Uso do nome social no Sistema Único de Saúde: Elementos para o debate sobre a assistência prestada a travestis e transexuais. Physis 2017, 27, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.; Diamond, M.; Green, J.; Karmic, D.; Reed, T.; Whittle, S.; Wylie, K. Transgender people: Health at the margins of society. Lancet 2016, 388, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.W.S.; Meira, C.K.; Azevedo, D.M.; Sena, R.C.F.; Lins, S.L.F.; Dantas, E.S.O.; Miranda, F.A.N. Fatores associados à ideação suicida em travestis e transexuais assistidas por organizações não governamentais. Cien Saude Colet. 2021, 26, 4955–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.A.; Reisner, S.L.; Onorato, S.E. Beyond Bathrooms--Meeting the Health Needs of Transgender People. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.W.S.; Souza, E.F.L.; Sena, R.C.F.; Moura, I.B.L.; Sobreira, M.V.S.; Miranda, F.A.N. Situações de violência contra travestis e transexuais em um município do nordeste brasileiro. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2016, 37, e56407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moreira, G.A.R. Manifestações de violência institucional no contexto da atenção em saúde às mulheres em situação de violência sexual. Saúde Soc. 2020, 29, e80895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, M. Violência Institucional e Transexualidade: Desafios para o Serviço Social. Rev. Praia Vermelha 2015, 25, 209–233. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, Y.N.; Schraiber, L.B. Violência institucional e humanização em saúde: Apontamentos para o debate. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2017, 22, 3013–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, S.P.; Maharaj, P. Structural violence on the margins of society: LGBT student access to health services. Agenda 2020, 34, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulavu, M.; Menon, J.A.; Mulubwa, C.; Matenga, T.F.L.; Nguyen, H.; MacDonell, K.; Wang, B.; Mweemba, O. Psychosocial challenges and coping strategies among people with minority gender and sexual identities in Zambia: Health promotion and human rights implications. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 2173201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenagy, G.P. Transgender health: Findings from two needs assessment studies in Philadelphia. Health Social. Work. 2005, 30, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miskolci, R.; Signorelli, M.C.; Canavese, D.; Teixeira, F.B.; Polidoro, M.; Moretti-Pires, R.O.; Souza, M.H.T.; Pereira, P.P.G. Health challenges in the LGBTI+ population in Brazil: A scenario analysis through the triangulation of methods. Cien Saude Colet. 2022, 27, 3815–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihadeh, N.A.; Pessoa, E.M.; Silva, F.F. A (in)visibilidade do acolhimento no âmbito da saúde: Em pauta as experiências de integrantes da comunidade LGBTQIA+. Barbarói 2021, 58, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocon, P.C.; Wandekoken, K.D.; Barros, M.E.B.; Duarte, M.J.O.; Sodré, F. Acesso à saúde pela população trans no Brasil: Nas entrelinhas da revisão integrativa. Trab. Educ. Saúde 2020, 18, e0023469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristowe, K.; Hodson, M.; Wee, B.; Almack, K.; Johnson, K.; Daveson, B.A.; Koffman, J.; McEnhill, L.; Harding, R. Recommendations to reduce inequalities for LGBT people facing advanced illness: ACCESSCare national qualitative interview study. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, T.S.H.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Suresh, M.; Isac, S.; Ramesh, B.M.; Moses, S. Personal, interpersonal and structural challenges to accessing HIV testing, treatment and care services among female sex workers, men who have sex with men and transgenders in Karnataka state, South India. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2012, 66, ii42–ii48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Patel, T. Inaccessible and stigmatizing: LGBTQ+ youth perspectives of services and sexual violence. LGBT Youth 2022, 20, 632–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evens, E.; Lanham, M.; Santi, K.; Cooke, J.; Ridgeway, K.; Morales, G.; Parker, C.; Brennan, C.; Bruin, M.; Desrosiers, P.C.; et al. Experiences of gender-based violence among female sex workers, men who have sex with men, and transgender women in Latin America and the Caribbean: A qualitative study to inform HIV programming. BMC Int. 2019, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azucar, D.; Slay, L.; Valerio, D.G.; Kipke, M.D. Barriers to COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake in the LGBTQIA Community. Am. J. Public. Health 2022, 112, 405–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, R.; Murta, D.; Facchini, R.; Meneghel, S.N. Gênero, direitos sexuais e suas implicações na saúde. Saúde Colet. 2018, 23, 1997–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shires, D.A.; Jaffee, K. Factors associated with health care discrimination experiences among a national sample of female-to-male transgender individuals. Health Soc. Work 2015, 40, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logie, C.; James, L.; Tharao, W.; Loutfy, M.R. “We don’t exist”: A qualitative study of marginalization experienced by HIV-positive lesbian, bisexual, queer and transgender women in Toronto, Canada. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2012, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, P.; Johnston, L. Rethinking Transgender Identities: Reflections from Around the Globe; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, J.G. Transfobia e crimes de ódio: Assassinatos de pessoas transgênero como genocídio. (In)visibilidade Trans 2. História Agora 2013, 16, 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI Manuals. Available online: https://jbi.global/ebp#jbi-manuals (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.L.M.; Fracolli, L.A. Revisão sistemática de literatura e metassíntese qualitativa: Considerações sobre sua aplicação na pesquisa em enfermagem. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2008, 17, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslandes, S.F.; Gomes, R.; Minayo, M.C.S. Pesquisa Social: Teoria, Método e Criatividade, 29th ed.; Vozes: Petrópolis, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia, R.M.G. Perfil dos trabalhadores da atenção básica em saúde no município de São Paulo: Região norte e central da cidade. Saúde Soc. 2011, 20, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2024. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Xavier, J.; Bradford, J.; Hendricks, M.; Safford, L.; McKee, R.; Martin, E.; Honnold, J.A. Transgender health care access in Virginia: A qualitative study. Int. J. Transgenderism 2013, 14, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosenko, K.; Rintamaki, L.; Raneym, S.; Maness, K. Transgender Patient Perceptions of Stigma in Health Care Contexts. Med. Care 2013, 51, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, T.; Shannon, K.; Pierre, L.; Small, W.; Krüsi, A.; Kerr, T. A qualitative study of transgender individuals’ experiences in residential addiction treatment settings: Stigma and inclusivity. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2015, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.H.T.; Malvasi, P.; Signorelli, M.C.; Pereira, P.P.G. Violência e sofrimento social no itinerário de travestis de Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2015, 31, 676–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, T.; Krusi, A.; Pierre, L.; Smith, A.; Small, W.; Shannon, K. Experiences of Trans Women and Two-Spirit Persons Accessing Women-Specific Health and Housing Services in a Downtown Neighborhood of Vancouver, Canada. LGBT Health 2016, 3, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritterbusch, A.E.; Salazar, C.C.; Correa, A. Stigma-related access barriers and violence against trans women in the Colombian healthcare system. Glob. Public Health 2018, 13, 1831–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, E.A.; Tape, C.; Garber, N.; Bowman, S.; Choo, E.K. “Sometimes You Feel Like the Freak Show”: A qualitative assessment of emergency care experiences among transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2018, 71, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, S.; Brigeiro, M. Experiences of transgender women/transvestites with access to health services: Progress, limits, and tensions. Cad. Saúde Pública 2019, 35, e00111318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Nanteza, J.; Sebyala, Z.; Bbaale, J.; Sande, E.; Poteat, T.; Kiyingi, H.; Hladik, W. HIV and transgender women in Kampala, Uganda—Double Jeopardy. Double Jeopardy Cult. Health Sex. 2019, 21, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, A.E.; Kuvalanka, K.A.; Budge, S.L.; Benz, M.B.; Smith, J.Z. Health Care Experiences of Transgender Binary and Nonbinary University Students. Couns. Psychol. 2019, 47, 59–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Khan, S.; Lorway, R. Following the divine: An ethnographic study of structural violence among transgender in South India. Cult. Health Sex. 2019, 21, 1240–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Jaramillo, M.; Mendoza, Á.; Acevedo, N.; Forero-Martínez, L.J.; Sánchez, S.M.; Rivillas-García, J.C. How to adapt sexual and reproductive health services to the needs and circumstances of trans people— a qualitative study in Colombia. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.G.; Abreu, P.D.; Araújo, E.C.; Santana, A.D.S.; Sousa, J.C.; Lyra, J.; Santos, C.B. Vulnerability in the health of young transgender women living with HIV/AIDS. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20190046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe-Duncan, A.; Olawale, R. Context, Types, and Consequences of Violence Across the Life Course: A Qualitative Study of the Lived Experiences of Transgender Women Living with HIV. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 37, 2242–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, S.L.; Silva-Santisteban, A.; Salazar, X.; Vilela, J.; D’Amico, L.; Perez-Brumer, A. “Existimos”: Health and social needs of transgender men in Lima, Peru. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.S.; Salimena, A.M.O.; Penna, L.H.G.; Paraíso, A.F.; Ramos, C.M.; Alves, M.S.; Pacheco, Z.M.L. O vivido de mulheres trans ou travestis no acesso aos serviços públicos de saúde. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2022, 75, e20210713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santander-Morillas, K.; Leyva-Moral, J.M.; Villar-Salgueiro, M.; Aguayo-González, M.; Téllez-Velasco, D.; Granel-Giménez, N.; Gómez-Ibáñez, R. TRANSALUD: A qualitative study of the healthcare experiences of transgender people in Barcelona (Spain). PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, W.; Pulerwitz, J.; Shoyemi, E.; Fernandez, A.; Adeniran, A.; Ejiogu, F.; Sangowawa, O.; Granger, K.; Dirisu, O.; Adedimeji, A.A. A qualitative study of how stigma influences HIV services for transgender men and women in Nigeria. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2022, 25, e25933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ssekamatte, T.; Nalugya, A.; Isunju, J.B.; Naume, M.; Oputan, P.; Kiguli, J.; Wafula, S.T.; Kibira, S.P.S.; Ssekamatte, D.; Orza, L.; et al. Help-seeking and challenges faced by transwomen following exposure to gender-based violence; a qualitative study in the Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area, Uganda. Int. J. Equity Health 2022, 21, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, A.D.F.; Bhaltazar, M.S.; Daniel, G.; Johnson, K.B.; Klepper, M.; Clark, K.D.; Baguso, G.N.; Cicero, E.; Allure, K.; Wharton, W.; et al. Barriers to accessing and engaging in healthcare as potential modifiers in the association between polyvictimization and mental health among Black transgender women. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, B.H.S.C.; Santos, G.S.; Porcino, C.; Mota, T.N.; Machuca-Contreras, F.A.; Oliveira, J.F.; Carvalho, E.S.S.; Sousa, A.R. Transphobia as a social disease: Discourses of vulnerabilities in trans men and transmasculine people. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2023, 76, e20220183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, M.K.M.R.; Moré, I.A.A.; Querino, R.A.; Oliveira, V.H. Transgender women’s experiences in the healthcare system: Visibility towards equity. Interface 2023, 27, e220369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyanga, N.; Isunju, J.B.; Ssekamatte, T.; Nalugya, A.; Oputan, P.; Kiguli, J.; Kibira, S.P.S.; Wafula, S.T.; Ssekamatte, D.; Mugambe, R.K.; et al. Understanding the effect of gender-based violence on uptake and utilisation of HIV prevention, treatment, and care services among transgender women: A qualitative study in the greater Kampala metropolitan area, Uganda. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, D.; Coleman, T.; Travers, R.; Aversa, I.; Schmid, E.; Coulombe, S.; Wilson, C.; Woodford, M.R.; Davis, C. ‘I don’t want to have to teach every medical provider’: Barriers to care among non-binary people in the Canadian healthcare system. Cult. Health Sex. 2023, 26, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atuk, T. “If I knew you were a travesti, I wouldn’t have touched you”: Iatrogenic violence and trans necropolitics in Turkey. Social. Sci. Med. 2024, 345, 116693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, L.; Perilo, M.; Braz, C.A.; Pedrosa, C. Políticas de saúde para lésbicas, gays, bissexuais, travestis e transexuais no Brasil: Em busca de universalidade, integralidade e equidade. Sex. Salud Soc. 2011, 9, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, F.B. Histórias que não têm era uma vez: As (in)certezas da transexualidade. Estud. Fem. 2014, 20, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, D.F.; Carvalho, M.V.F.; Pereira, N.R.; Rocha, N.T.; Neves, V.R.; Rosa, A.S. Nursing Care for the transgender population: Genders from the perspective of professional practice. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2019, 72, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocon, P.C.; Sodré, F.; Zamboni, J.; Rodrigues, A.; Roseiro, M.C.F. What trans people expect of the Brazilian National Health System? Interface 2018, 22, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, G.; Murta, D. Reflexões sobre a possibilidade da despatologização da transexualidade e a necessidade da assistência integral à saúde de transexuais no Brasil. Sex. Salud Soc. 2013, 14, 380–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.B.U.; Rashid, F.; Atif, I.; Hydrie, M.Z.; Fawad, M.W.B.; Muzaffar, H.Z.; Rehman, A.; Anjum, S.; Mehroz, M.B.; Haider, A.; et al. Challenges faced by marginalized communities such as transgenders in Pakistan. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2018, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.; Horton, R. Transgender health: An opportunity for global health equity. Lancet 2016, 388, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).