Evaluating Fatalism Among Breast Cancer Survivors in a Heterogeneous Hispanic Population: A Cross-Sectional Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Fatalism

2.2.2. Hispanic Origin

2.2.3. Acculturation

2.2.4. Fear of Recurrence

2.2.5. Other Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants

3.2. Fatalism Scores by Participant Characteristics

3.3. Characteristics of Fatalism

3.4. Factors Associated with Fatalism

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QOL | Quality of life |

| US | United States |

| FCDS | Florida Cancer Data System |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| MFM | Multidimensional Fatalism Measure |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts Figures for Hispanic/Latino Population 2024–2026; American Cancer Society, Inc.: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Newman, L.A.; Freedman, R.A.; Smith, R.A.; Star, J.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast cancer statistics 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts Figures 2024–2025; American Cancer Society, Inc.: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa, K.T.; Padilla, G.V.; Bohórquez, D.E.; Tejero, J.S.; Garcia, M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Latina women. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2006, 24, 19–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder, V.S.; Patil, S.; Thind, A.; Diamant, A.; Hudis, C.A.; Basch, E.; Maly, R.C. Return to work in low-income Latina and non-Latina white breast cancer survivors: A 3-year longitudinal study. Cancer 2012, 118, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eversley, R.; Estrin, D.; Dibble, S.; Wardlaw, L.; Pedrosa, M.; Favila-Penney, W. Post-treatment symptoms among ethnic minority breast cancer survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2005, 32, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almatkyzy, G.; Mojica, C.M.; Stroup, A.M.; Llanos, A.A.; O’Malley, D.; Xu, B.; Tsui, J. Predictors of health-related quality of life among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White breast cancer survivors in New Jersey. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2021, 39, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoles-Springer, A.M.; Ortiz, C.; O’Brien, H.; Diaz-Mendez, M.; Perez-Stable, E.J. Use of cancer support groups among Latina breast cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2007, 1, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanez, B.; Thompson, E.H.; Stanton, A.L. Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: A systematic review of the literature. J. Cancer Surviv. 2011, 5, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Smith, R.G.; Petronis, V.M.; Antoni, M.H. Quality of life among long-term survivors of breast cancer: Different types of antecedents predict different classes of outcomes. Psychooncology 2006, 15, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanez, B.; Stanton, A.L.; Maly, R.C. Breast cancer treatment decision making among Latinas and non-Latina Whites: A communication model predicting decisional outcomes and quality of life. Health Psychol. 2012, 31, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powe, B.D.R.; Finnie, R. Cancer Fatalism: The State of Science. Cancer Nurs. 2003, 26, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Class, M.; Perret-Gentil, M.; Kreling, B.; Caicedo, L.; Mandelblatt, J.; Graves, K.D. Quality of life among immigrant Latina breast cancer survivors: Realities of culture and enhancing cancer care. J. Cancer Educ. 2011, 26, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, K.D.; Jensen, R.E.; Canar, J.; Perret-Gentil, M.; Leventhal, K.G.; Gonzalez, F.; Caicedo, L.; Jandorf, L.; Kelly, S.; Mandelblatt, J. Through the lens of culture: Quality of life among Latina breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 136, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster, s.v. “Fatalism (n)”. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fatalism (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Abraído-Lanza, A.F.; Martins, M.C.; Shelton, R.C.; Flórez, K.R. Breast Cancer Screening Among Dominican Latinas: A Closer Look at Fatalism and Other Social and Cultural Factors. Health Educ. Behav. 2015, 42, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powe, B.D.; Hamilton, J.; Brooks, P. Perceptions of Cancer Fatalism and Cancer Knowledge. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2006, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remennick, L. The Challenge of Early Breast Cancer Detection among Immigrant and Minority Women in Multicultural Societies. Breast J. 2006, 12, S103–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, F.; Beshai, S.; Del Rosario, N. Fatalism and Depressive Symptoms: Active and Passive Forms of Fatalism Differentially Predict Depression. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 3211–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrinten, C.; Wardle, J.; Marlow, L.A. Cancer fear and fatalism among ethnic minority women in the United Kingdom. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 114, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustillo, N.E.; McGinty, H.L.; Dahn, J.R.; Yanez, B.; Antoni, M.H.; Kava, B.R.; Penedo, F.J. Fatalism, medical mistrust, and pretreatment health-related quality of life in ethnically diverse prostate cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.; Wang, J.H.-Y. Fatalism and Psychological Distress Among Chinese American Breast Cancer Survivors: Mediating Role of Perceived Self-control and Fear of Cancer Recurrence. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2023, 30, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Epel, O.; Friedman, N.; Lernau, O. Fatalism and Mammography in a Multicultural Population. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2009, 36, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, I.; Kaviani, A.; Fakhrejahani, E.; Mehrdad, N.; Hazar, N.; Karbakhsh, M. Religious, Cultural, and Social Beliefs of Iranian Rural Women about Breast Cancer: A Qualitative Study. Arch. Breast Cancer 2014, 1, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullatte, M.M.; Brawley, O.; Kinney, A.; Powe, B.; Mooney, K. Religiosity, Spirituality, and Cancer Fatalism Beliefs on Delay in Breast Cancer Diagnosis in African American Women. J. Relig. Health 2010, 49, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida Department of Health. Procedure Guide for Studies That Utilize Patient Identifiable Data from the Florida Cancer Data System. Available online: https://fcds.med.miami.edu/downloads/datarequest/ProcedureGuide_Revised_March2016.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Lee, E.; Sukhu, B.D.; de Azevedo Daruge, M.E.; Chung, J.; Hines, R.B.; Loerzel, V. Recruitment Feasibility of Hispanic Women in Breast Cancer Survivorship Research Using State Cancer Registry Procedures. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esparza, O.A.; Wiebe, J.S.; Quiñones, J. Simultaneous Development of a Multidimensional Fatalism Measure in English and Spanish. Curr. Psychol. 2015, 34, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenti, G.D.; Faraci, P. Instruments measuring fatalism: A systematic review. Psychol. Assess. 2022, 34, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2005, 29, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.J.; Bennett, K.K.; Clark, J.R.; Harry, K.M.; Tiznado, D.; Eways, K.R.; Ramirez, A.; Marte, R.M. The Interaction between Fatalism and Religious Attendance is Negatively Associated with Mental Health-Related Quality of Life in Hispanic/Latino Americans Low in Acculturation. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2020, 22, 521. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/index.htm (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Kandula, N.R.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Chan, C.; Daviglus, M.L.; Jackson, S.A.; Ni, H.; Schreiner, P.J. Association of Acculturation Levels and Prevalence of Diabetes in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, C.; Trock, B.; Rimer, B.K.; Jepson, C.; Brody, D.; Boyce, A. Psychological side effects of breast cancer screening. Health Psychol. 1991, 10, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettschneider, C.; Leicht, H.; Bickel, H.; Dahlhaus, A.; Fuchs, A.; Gensichen, J.; Maier, W.; Riedel-Heller, S.; Schafer, I.; Schon, G.; et al. Relative impact of multimorbid chronic conditions on health-related quality of life--results from the MultiCare Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, J.P.L. Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Multiple Imputation Strategies for the Statistical Analysis of Incomplete Data Sets; Erasmus University: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, A.G.; Suarez, L.; Laufman, L.; Barroso, C.; Chalela, P. Hispanic women’s breast and cervical cancer knowledge, attitudes, and screening behaviors. Am. J. Health Promot. 2000, 14, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, D.; Blanco, A.; Bajo, M.; Stavraki, M. Fatalism and Well-Being Across Hispanic Cultures: The Social Fatalism Scales (SFS). Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 124, 929–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, R.M.; Ureda, J.R.; Parker, V.G. Importance of Fatalism in Understanding Mammography Screening in Rural Elderly Women. J. Women Aging 2001, 13, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukkarieh-Haraty, O.; Egede, L.E.; Kharma, J.A.; Bassil, M. Predictors of Diabetes Fatalism Among Arabs: A Cross-Sectional Study of Lebanese Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Relig. Health 2018, 57, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, D.V.; Brown, A.; Lopez, M.H. Black and Hispanic Americans See Their Origins as Central to Who They Are, Less So for White Adults; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Otero-Sabogal, R.; Stewart, S.; Sabogal, F.; Brown, B.A.; Pérez-Stable, E.J. Access and Attitudinal Factors Related to Breast and Cervical Cancer Rescreening: Why are Latinas Still Underscreened? Health Educ. Behav. 2003, 30, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, D.M.; Harding, J.F.; Paulsell, D.; English, B.; Hijjawi, G.R.; Ng’andu, J. Economic Well-Being And Health: The Role Of Income Support Programs In Promoting Health And Advancing Health Equity. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 1700–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, M.P.; Castro, F.G.; Coe, K. Acculturation and cervical cancer: Knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors of Hispanic women. Women Health 1996, 24, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Unger, J.B.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Szapocznik, J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. Am. Psychol. 2010, 65, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, H.; Çapik, C. Are Health Fatalism and Styles of Coping with Stress Affected by Poverty? A Field Study. Iran. J. Public Health 2023, 52, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics/Categories | Total | Colombian | Cuban | Dominican | Mexican | Puerto Rican | Venezuelan | Other Hispanic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants | 390 (100.0%) | 34 (8.7%) | 25 (6.4%) | 29 (7.4%) | 22 (5.6%) | 210 (53.8%) | 24 (6.2%) | 46 (11.8%) | |

| Mean (SD) | p-value | ||||||||

| Age at diagnosis | 55.0 (11.9) | 56.4 (9.8) | 57.1 (12.0) | 55.7 (13.3) | 50.0 (12.2) | 55.7 (11.9) | 53.5 (12.3) | 52.3 (11.1) | 0.177 |

| Current age | 59.5 (11.8) | 60.4 (9.6) | 61.6 (12.3) | 60.0 (13.0) | 55.0 (11.7) | 60.2 (11.8) | 57.9 (12.2) | 57.6 (11.6) | 0.375 |

| Years since diagnosis | 4.8 (2.0) | 4.8 (2.1) | 4.6 (1.9) | 4.4 (1.9) | 5.1 (2.1) | 4.6 (1.9) | 4.6 (1.8) | 5.6 (2.9) | 0.089 |

| Years lived in US | 32.9 (19.4) | 33.6 (18.2) | 45.4 (17.9) | 40.9 (16.7) | 37.7 (16.5) | 31.3 (19.9) | 13.5 (11.1) | 35.6 (16.1) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index | 28.7 (5.7) | 26.7 (4.8) | 29.3 (5.6) | 28.1 (5.4) | 29.5 (6.5) | 29.2 (5.9) | 27.8 (6.2) | 27.9 (4.4) | 0.194 |

| N (%) | p-value | ||||||||

| Race | 0.029 | ||||||||

| White | 183 (46.9) | 15 (44.1) | 5 (20.0) | 20 (69.0) | 12 (54.5) | 98 (46.7) | 9 (37.5) | 24 (52.2) | |

| Nonwhite | 207 (53.1) | 19 (55.9) | 20 (80.0) | 9 (31.0) | 10 (45.5) | 112 (53.3) | 15 (62.5) | 22 (47.8) | |

| Current smoking | 0.729 | ||||||||

| No | 372 (95.4) | 32 (94.1) | 23 (92.0) | 29 (100.0) | 22 (100.0) | 200 (95.2) | 23 (95.8) | 43 (93.5) | |

| Yes | 15 (3.8) | 2 (5.9) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (3.8) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (4.3) | |

| Marital status | 0.074 | ||||||||

| Married | 234 (60.0) | 20 (58.8) | 20 (80.0) | 14 (48.3) | 15 (68.2) | 117 (55.7) | 16 (66.7) | 32 (69.6) | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 151 (38.7) | 14 (41.2) | 4 (16.0) | 15 (51.7) | 6 (27.3) | 90 (42.9) | 8 (33.3) | 14 (30.4) | |

| Household income | 0.090 | ||||||||

| <USD 20,000 | 67 (17.2) | 10 (29.4) | 3 (12.0) | 6 (20.7) | 2 (9.1) | 37 (17.6) | 3 (12.5) | 6 (13.0) | |

| USD 20,000–<USD 75,000 | 176 (45.1) | 14 (41.2) | 5 (20.0) | 11 (37.9) | 13 (59.1) | 100 (47.6) | 13 (54.2) | 20 (43.5) | |

| ≥USD 75,000 | 92 (23.6) | 7 (20.6) | 11 (44.0) | 6 (20.7) | 3 (13.6) | 48 (22.9) | 3 (12.5) | 14 (30.4) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 55 (14.1) | 3 (8.8) | 6 (24.0) | 6 (20.7) | 4 (18.2) | 25 (11.9) | 5 (20.8) | 6 (13.0) | |

| Education level | 0.025 | ||||||||

| ≤High school | 122 (31.3) | 13 (38.2) | 9 (36.0) | 11 (37.9) | 13 (59.1) | 60 (28.6) | 4 (16.7) | 12 (26.1) | |

| Some college+ | 267 (68.5) | 21 (61.8) | 16 (64.0) | 18 (62.1) | 8 (36.4) | 150 (71.4) | 20 (83.3) | 34 (73.9) | |

| Multimorbidity | 0.309 | ||||||||

| No | 157 (40.3) | 16 (47.1) | 10 (40.0) | 11 (37.9) | 12 (54.5) | 75 (35.7) | 12 (50.0) | 21 (45.7) | |

| Yes | 218 (55.9) | 18 (52.9) | 14 (56.0) | 17 (58.6) | 9 (40.9) | 129 (61.4) | 11 (45.8) | 20 (43.5) | |

| Language used at home | <0.001 | ||||||||

| More Spanish | 203 (52.1) | 22 (64.7) | 9 (36.00 | 13 (44.8) | 10 (45.5) | 112 (53.3) | 22 (91.7) | 15 (32.6) | |

| Both equally | 86 (22.1) | 5 (14.7) | 4 (16.0) | 7 (24.1) | 1 (4.5) | 57 (27.1) | 1 (4.2) | 11 (23.9) | |

| More English | 99 (25.4) | 7 (20.6) | 12 (48.0) | 9 (31.0) | 10 (45.5) | 41 (19.5) | 1 (4.2) | 19 (41.3) | |

| Birthplace | 0.167 | ||||||||

| US | 308 (79.0) | 31 (91.2) | 18 (72.0) | 23 (79.3) | 18 (81.8) | 159 (75.7) | 23 (95.8) | 36 (78.3) | |

| Non-US | 81 (20.8) | 3 (8.8) | 7 (28.0) | 6 (20.7) | 4 (18.2) | 50 (23.8) | 1 (4.2) | 10 (21.7) | |

| Stage | 0.441 | ||||||||

| In situ | 65 (16.7) | 7 (20.6) | 3 (12.0) | 7 (24.1) | 4 (18.2) | 35 (16.7) | 1 (4.2) | 8 (17.4) | |

| Localized | 158 (40.5) | 12 (35.3) | 12 (48.0) | 11 (37.9) | 7 (31.8) | 87 (41.4) | 17 (70.8) | 12 (26.1) | |

| Regional/distant | 66 (16.9) | 4 (11.8) | 4 (16.0) | 5 (17.2) | 3 (13.6) | 41 (19.5) | 2 (8.3) | 7 (15.2) | |

| Surgery | 0.467 | ||||||||

| No | 15 (3.8) | 3 (8.8) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (3.3) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (4.3) | |

| Breast-conserving surgery | 199 (51.0) | 20 (58.8) | 18 (72.0) | 16 (55.2) | 12 (54.5) | 102 (48.6) | 10 (41.7) | 21 (45.7) | |

| Mastectomy | 176 (45.1) | 11 (32.4) | 6 (24.0) | 12 (41.4) | 10 (45.5) | 101 (48.1) | 13 (54.2) | 23 (50.0) | |

| Radiation therapy | 0.160 | ||||||||

| No | 209 (53.6) | 16 (47.1) | 8 (32.0) | 15 (51.7) | 11 (50.0) | 115 (54.8) | 13 (54.2) | 31 (67.4) | |

| Yes | 170 (43.6) | 18 (52.9) | 15 (60.0) | 14 (48.3) | 10 (45.5) | 89 (42.4) | 11 (45.8) | 13 (28.3) | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.008 | ||||||||

| No | 217 (55.6) | 21 (61.8) | 18 (72.0) | 15 (51.7) | 9 (40.9) | 117 (55.7) | 6 (25.0) | 31 (67.4) | |

| Yes | 172 (44.1) | 12 (35.3) | 7 (28.0) | 14 (48.3) | 13 (59.1) | 93 (44.3) | 18 (75.0) | 15 (32.6) | |

| ER status | 0.347 | ||||||||

| Negative | 54 (13.8) | 5 (14.7) | 3 (12.0) | 4 (13.8) | 6 (27.3) | 24 (11.4) | 6 (25.0) | 6 (13.0) | |

| Positive | 319 (81.8) | 27 (79.4) | 22 (88.0) | 22 (75.9) | 15 (68.2) | 176 (83.8) | 18 (75.0) | 39 (84.8) | |

| PR status | 0.673 | ||||||||

| Negative | 98 (25.1) | 8 (23.5) | 6 (24.0) | 6 (20.7) | 9 (40.9) | 51 (24.3) | 8 (33.3) | 10 (21.7) | |

| Positive | 270 (69.2) | 22 (64.7) | 18 (72.0) | 20 (69.0) | 12 (54.5) | 148 (70.5) | 16 (66.7) | 34 (73.9) | |

| HER2 status | 0.082 | ||||||||

| Negative | 253 (64.9) | 21 (61.8) | 17 (68.0) | 20 (69.0) | 13 (59.1) | 139 (66.2) | 14 (58.3) | 29 (63.0) | |

| Positive | 60 (15.4) | 2 (5.9) | 4 (16.0) | 1 (3.4) | 5 (22.7) | 31 (14.8) | 9 (37.5) | 8 (17.4) | |

| Fear of recurrence | 0.470 | ||||||||

| Low | 132 (33.8) | 13 (38.2) | 12 (48.0) | 8 (27.6) | 10 (45.5) | 63 (30.0) | 10 (41.7) | 16 (34.8) | |

| Moderate | 201 (51.5) | 19 (55.9) | 11 (44.0) | 15 (51.7) | 11 (50.0) | 109 (51.9) | 13 (54.2) | 23 (50.0) | |

| High | 50 (12.8) | 2 (5.9) | 2 (8.0) | 6 (20.7) | 1 (4.5) | 33 (15.7) | 1 (4.2) | 5 (10.9) | |

| Variable | Category | N | Estimated Mean (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 390 | 16.4 (15.8–17.0) | ||

| Hispanic origin | Colombian | 34 | 13.3 (11.2–15.4) | 0.060 |

| Cuban | 25 | 15.6 (13.1–18.1) | ||

| Dominican | 29 | 17.4 (15.1–19.7) | ||

| Mexican | 22 | 17.8 (15.2–20.5) | ||

| Puerto Rican | 210 | 16.7 (15.9–17.6) | ||

| Venezuelan | 24 | 17.4 (14.9–132.8) | ||

| Other Hispanic | 46 | 15.8 (14.1–17.7) | ||

| Current age (years) | 20–<40 | 15 | 18.7 (15.5–21.8) | 0.377 |

| 40–<55 | 131 | 16.6 (15.5–17.7) | ||

| 55–70 | 159 | 15.9 (14.9–16.9) | ||

| ≥70 | 85 | 16.7 (15.3–18.0) | ||

| Race | White | 207 | 15.9 (15.1–16.8) | 0.111 |

| Non-white | 183 | 17.0 (16.0–17.9) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | <25 | 109 | 16.2 (15.1–17.4) | 0.709 |

| 25–<30 | 141 | 16.3 (15.2–17.3) | ||

| ≥30 | 135 | 16.8 (15.7–17.9) | ||

| Current smoking | No | 372 | 16.3 (15.7–17.0) | 0.304 |

| Yes | 15 | 18.1 (14.8–21.3) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 234 | 16.6 (15.7–17.4) | 0.770 |

| Unmarried | 151 | 16.4 (15.3–17.4) | ||

| Household income | <USD 20,000 | 67 | 18.5 (17.0–20.0) | 0.004 |

| USD 20,000–<USD 75,000 | 176 | 16.1 (15.2–17.0) | ||

| ≥USD 75,000 | 92 | 15.1 (13.8–16.3) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 55 | 17.1 (15.5–18.8) | ||

| Education level | ≤High school | 122 | 18.2 (17.1–19.3) | <0.001 |

| Some college or more | 267 | 15.6 (14.8–16.4) | ||

| Language use at home | More Spanish | 203 | 17.1 (16.2–17.9) | 0.007 |

| Both equally | 86 | 17.0 (15.6–18.3) | ||

| More English | 99 | 14.7 (13.5–16.0) | ||

| Birthplace | United States | 81 | 15.8 (14.4–17.2) | 0.314 |

| Outside United States | 308 | 16.6 (15.9–17.3) | ||

| Multimorbidity | No | 157 | 16.7 (15.7–17.7) | 0.513 |

| Yes | 218 | 16.2 (15.4–17.1) | ||

| Cancer stage | In Situ | 65 | 16.2 (14.6–17.7) | 0.574 |

| Localized | 158 | 16.1 (15.1–17.1) | ||

| Regional/distant | 66 | 17.0 (15.5–18.6) | ||

| Surgery | No | 15 | 13.8 (10.6–17.0) | 0.259 |

| Breast-conserving surgery | 199 | 16.6 (15.7–17.5) | ||

| Mastectomy | 176 | 16.5 (15.5–17.4) | ||

| Radiotherapy | No | 209 | 16.4 (15.6–17.3) | 0.895 |

| Yes | 170 | 16.4 (15.4–17.3) | ||

| Chemotherapy | No | 217 | 16.3 (15.4–17.1) | 0.527 |

| Yes | 172 | 16.7 (15.7–17.6) | ||

| Estrogen receptor | Negative | 54 | 16.3 (14.6–18.0) | 0.881 |

| Positive | 319 | 16.4 (15.7–17.1) | ||

| Years since diagnosis (years) | <2 | 42 | 14.1 (12.2–16.1) | 0.043 |

| 2–<5 | 216 | 16.8 (16.0–17.7) | ||

| 5–<10 | 132 | 16.5 (15.4–17.6) | ||

| Years lived in US | <10 | 64 | 16.1 (14.5–17.6) | 0.718 |

| 10–<30 | 119 | 16.8 (15.6–17.9) | ||

| ≥30 | 206 | 16.3 (15.4–17.2) | ||

| Fear of recurrence | Low | 132 | 15.6 (14.5–16.7) | 0.039 |

| Moderate | 201 | 16.6 (15.7–17.4) | ||

| High | 50 | 18.2 (16.5–20.0) |

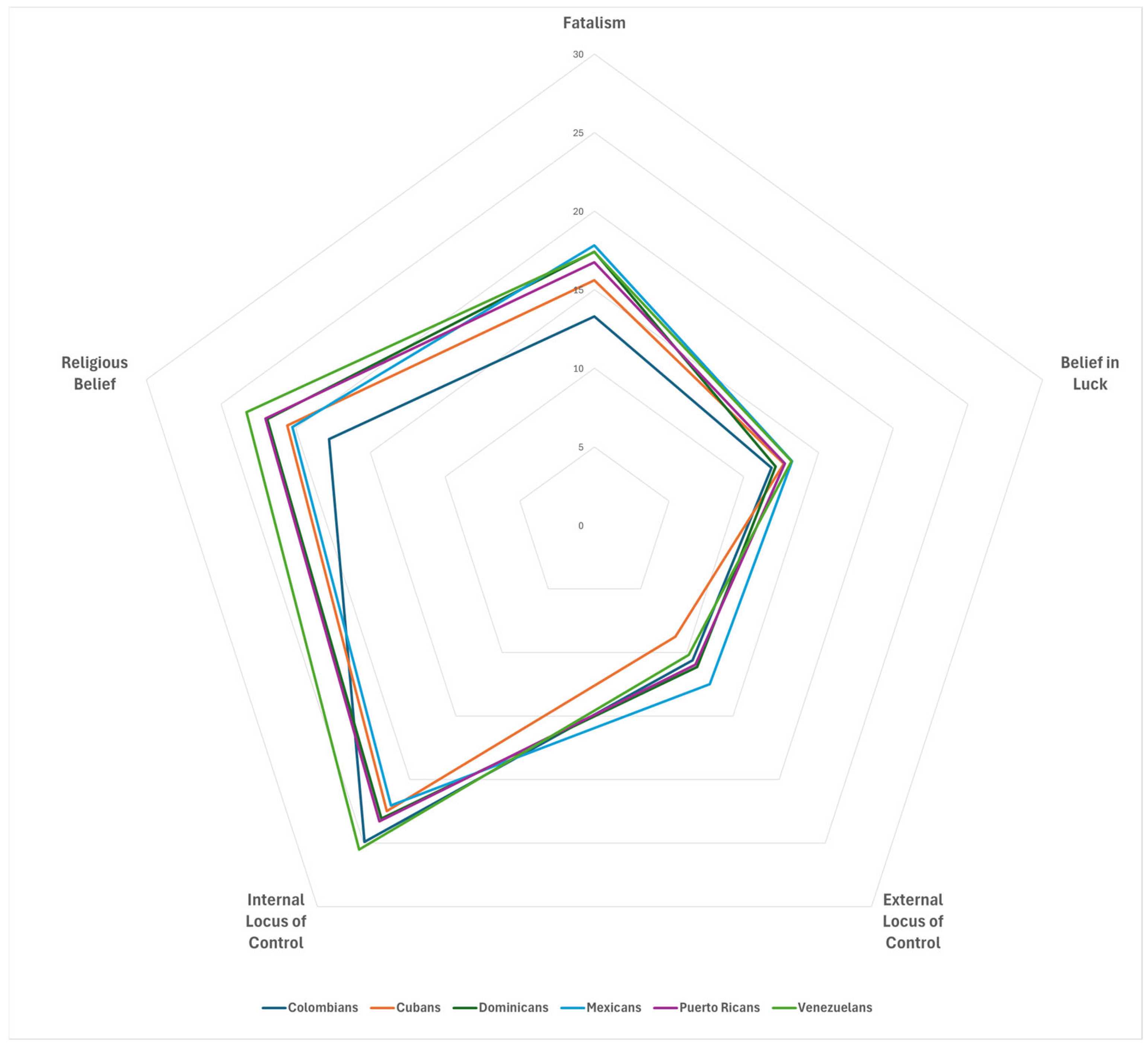

| Variable | Fatalism | Religious Belief | External Locus of Control | Internal Locus of Control | Belief in Luck |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 16.4 (6.3) | 21.3 (7.5) | 10.9 (5.3) | 23.4 (5.0) | 12.6 (4.7) |

| Correlation Matrix: Correlation Coefficient (p-value) | |||||

| Religious belief | 0.394 (p < 0.001) | ||||

| External locus of control | 0.400 (p < 0.001) | 0.125 (p = 0.014) | |||

| Internal locus of control | 0.150 (p = 0.003) | −0.003 (p = 0.949) | −0.045 (p = 0.677) | ||

| Belief in luck | 0.273 (p < 0.001) | 0.156 (p = 0.002) | 0.384 (p < 0.001) | 0.060 (p = 0.234) | |

| Characteristics | Parameter | b | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 19.2 | 2.4 | <0.0001 | |

| Hispanic origin (Ref: Puerto Rican) | Colombian | −3.7 | 1.1 | 0.001 |

| Cuban | −0.9 | 1.3 | 0.509 | |

| Dominican | −0.1 | 1.2 | 0.920 | |

| Mexican | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.622 | |

| Venezuelan | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.314 | |

| Other Hispanic | −0.7 | 1.0 | 0.480 | |

| Current age (Ref: 20–<40) | 40–<55 | −1.9 | 1.7 | 0.264 |

| 55–<70 | −3.0 | 1.7 | 0.082 | |

| 70+ | −3.3 | 1.8 | 0.069 | |

| Race (Ref: white) | Non-white | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.289 |

| Household income (Ref: <USD 20,000) | USD 20,000–<USD 75,000 | −2.4 | 0.9 | 0.007 |

| ≥USD 75,000 | −2.4 | 1.1 | 0.029 | |

| Prefer not to answer | −1.2 | 1.1 | 0.273 | |

| Education (Ref: ≤ high school) | Some college+ | −2.0 | 0.7 | 0.008 |

| Language use at home (Ref: more Spanish) | Both equally | −0.2 | 0.9 | 0.804 |

| More English | −1.9 | 0.9 | 0.043 | |

| Years lived in US (Ref: <10) | 10–<30 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.380 |

| 30+ | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.110 | |

| Years since diagnosis (Ref: <2) | 2–<5 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.061 |

| ≥5 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 0.052 | |

| Fear of recurrence (Ref: low) | Moderate | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.225 |

| High | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.103 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopez Torralba, L.; Sukhu, B.; de Azevedo Daruge, M.E.; Chung, J.; Loerzel, V.; Lee, E. Evaluating Fatalism Among Breast Cancer Survivors in a Heterogeneous Hispanic Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080461

Lopez Torralba L, Sukhu B, de Azevedo Daruge ME, Chung J, Loerzel V, Lee E. Evaluating Fatalism Among Breast Cancer Survivors in a Heterogeneous Hispanic Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(8):461. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080461

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopez Torralba, Liara, Brian Sukhu, Maria Eduarda de Azevedo Daruge, Jongik Chung, Victoria Loerzel, and Eunkyung Lee. 2025. "Evaluating Fatalism Among Breast Cancer Survivors in a Heterogeneous Hispanic Population: A Cross-Sectional Study" Current Oncology 32, no. 8: 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080461

APA StyleLopez Torralba, L., Sukhu, B., de Azevedo Daruge, M. E., Chung, J., Loerzel, V., & Lee, E. (2025). Evaluating Fatalism Among Breast Cancer Survivors in a Heterogeneous Hispanic Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Current Oncology, 32(8), 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080461