Using Unconventional Wisdom to Re-Assess and Rebuild the BRICS

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- 2000: The MSCI (Emerging Markets) index doubles within two years to reach 500 for the time. The shift from developed to emerging markets is starting. After two drops to 230 and 250 in 2001 and 2002, respectively, this closely-watched index will climb above 1300 in October 2007 without suffering any major setbacks.9

- 2000: Tata Tea buys Tetley Tea (UK).10

- 2000: John (Jack) C. Bogle, legendary investor and founder of the Vanguard Group ($5 trillion of assets under management, as of 2018), warns investors about the dangers of a “sound premise” and provides timeless advice against conventional wisdom (Bogle 2000).

- 2001: Jim O’Neill coins the term BRIC.

- 2001: China joins the WTO.

- 2002: UN Secretary General, K. Annan, introduces the idea of inclusive globalization in a speech at Yale University (Gemmill et al. 2002).

- 2005: Lenovo buys IBM’s PC division.

- 2007: against conventional wisdom on subprime loans and housing prices, John Paulson, hedge fund manager, places his bet and executes the best trade ever, being rewarded with billions of dollars and fame (Zuckerman 2010).

- 2008: The GFC starts with the collapse of Lehman Brothers (Mensi et al. 2016). The largest bankruptcy in US history; i.e., more than $600 bn, went against the conventional wisdom that Lehman was too big to fail and was going to be rescued by the US government like other financial institutions. It wasn’t and its collapse had many consequences in the financial markets, across industries and countries. It bankrupted two out of three of the American BIG THREE. It left Ford moribund with record losses of $14.6 billion and fueled the growth of EMNCs, such as Tata Motors and Geely. Except for Russia, which goes into isolation, the BRICS’ financial markets recouple with that of the US with increased linkages (Mensi et al. 2016) and later demonstrate the importance of stocks from developed countries in optimal portfolios (Mensi et al. 2017). High risks typically call for high rewards that will be delivered by the US stock market in a subsequent long-term bull market.

- 2008: Tata Motors buys Jaguar-Land Rover from Ford for $2.3 bn in cash.11

- 2008: China becomes a vital market for Ford since it passed the US as the largest market in the world for all automakers in 2010 and became their largest foreign market.

- 2008: According to McKinsey, the number of connected devices equals the world’s population.12

- 2008: Lenovo becomes the sponsor of the Beijing Olympics.

- 2009: Bernie Madoff is convicted and sentenced to 150 years in prison for the largest Ponzi scheme in history.

- 2009: GM files for bankruptcy after more than 100 years in business.

- 2009: from an all-time high of 1337 in 2007, the MSCI (Emerging Markets) index plummets to 499 in February 2009.13

- 2010: Geely acquires Volvo cars from Ford and could have been seen as a partner. However, additional moves by the EMNC indicate that it is becoming a competitor to reckon with, both in China and at home, not to mention in Europe.

- 2010: Grupo Bimbo (Mexico) acquires the North American fresh bakery business of Sara Lee.

- 2011: MSCI (Emerging Markets) index recovers from the 2009 crash and reaches 1204 (see footnote 13).

- 2012: the MOOC revolution starts: greater access to business education at a fraction of the cost. MOOC courses are offered to millions by Wharton, Harvard, MIT, etc.

- 2012: The end of globalization? (Rugman 2012). The conventional wisdom about the benefits of globalization starts to change. Globalization becomes the enemy of many. Populism (Mudambi 2018) and protectionism grow in the UK, US, Spain, Italy, Russia, China, and Brazil.

- 2012: Dalian Wanda Group (China) acquires AMC Theaters for $2.6 bn.

- 2013: Jim O’Neill retires from Goldman Sachs as Chairman of the Asset Management Division.

- 2015: Goldman Sachs closes its BRIC fund after years of losses and assets under management free-falling from $800 to $100 million.

- 2015: LinkedIn reaches 500 million users and is increasingly used by scholars to socialize their research.

- 2016: Brexit vote takes place. It catches financial markets and political science experts by surprise. Unaware of the consequences of leaving Europe, millions of British turn to google to better understand the EU that they just rejected in a historic vote.

- 2016: Haier buys GE’s appliances division for $5.4 billion.

- 2016: Donald Trump is elected President of the US.

- 2016: the MSCI (Emerging Markets) index plummets again to 742 (see footnote 13).

- 2017: President Trump announces his America First policy and exits the Transpacific Partnership Agreement which was going to reduce tariffs, create jobs, and boost trade.

- 2017: ChemChina completes the largest foreign takeover by a Chinese firm by acquiring Syngenta for $43 billion.14

- 2017: Geely buys Lotus (UK).

- 2018: the MSCI (Emerging Markets) index climbs to 1254 in January and loses 23.84% of its value by 2 January 2019, trading at the level of 955 (see footnote 13).

- 2018: amidst a trade war between the US and China ((Trump administration decision to impose 25 per cent tariffs on steel and 10 per cent aluminum imported from China, retaliation from China, and escalation with other tariffs between the two countries), the conventional wisdom on the permanence of free trade agreements and free-trade policies started after WWII is rocked to its core. Major financial markets enter correction territory.

- 2018: Geely buys a stake in the truckmaker AB Volvo and took a 10% stake in Daimler (parent company of Mercedes-Benz). All of these brands are sold in the US.

- Late August 2018: Geely announces the building of a new plant to produce bigger vehicles (trucks, SUVs, and cross-overs) and expected 90% of its cars to be electric by 2020. This confirms the growth of Geely both as an automaker but also as a threatening competitor to Ford.

3. Results

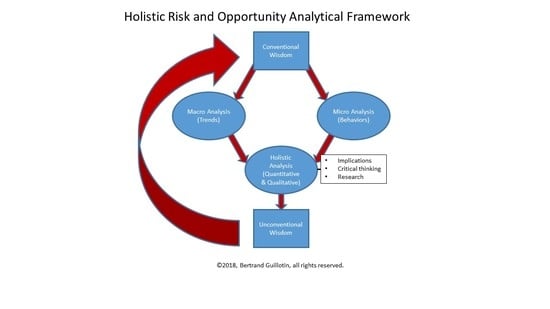

Finding Some Unconventional Wisdom to Derive Strategic Insights

“Policies that make an economy open to trade and investment with the rest of the world are needed for sustained economic growth. The evidence on this is clear. No country in recent decades has achieved economic success, in terms of substantial increases in living standards for its people, without being open to the rest of the world.”15

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahlstrom, David. 2010. Innovation and growth: How business contributes to society. Academy of Management Perspectives 24: 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Altbach, Philip G. 1998. Comparative Higher Education: Knowledge, the University, and Development. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Dudley, Caryn L. 2018. The Future of Work, Business Education, and the Role of AACSB: Keynote Address to the Academy of Legal Studies in Business, Annual Meeting, Savannah, Georgia, September 8, 2017. Journal of Legal Studies Education 35: 165–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beechler, Schon, and Mansour Javidan. 2007. Leading with a global mindset. In The Global Mindset. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 131–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bermiss, Y. Sekou, Edward J. Zajac, and Brayden G. King. 2013. Under construction: How commensuration and management fashion affect corporate reputation rankings. Organization Science 25: 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, Alexander. 2016. Why Brexit happened–and what to do next. Ted Talk, June. [Google Scholar]

- Bogle, John C. 2000. Common Sense on Mutual Funds: New Imperatives for the Intelligent Investor. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Ha-Joon. 2002. Kicking away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective. London: Anthem Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crafts, Nicholas, and Peter Fearon. 2010. Lessons from the 1930s Great Depression. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 26: 285–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Currie, Graeme, David Knights, and Ken Starkey. 2010. Introduction: A post-crisis critical reflection on business schools. British Journal of Management 21: s1–s5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardo, Mauro. 2004. Nobel Laureates and Twentieth-Century Physics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, Peter F. 2017. The New Society: The Anatomy of Industrial Order. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, Jean. 2018. US tariffs on steel and aluminum imports go into effect, leading to trade disputes. American Journal of International Law 112: 499–504. [Google Scholar]

- Gemmill, Barbara, Maria Ivanova, and Chee Yoke Ling. 2002. Designing a new architecture for global environmental governance. In World Summit for Sustainable Development Briefing Papers. Johannesburg: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Ghemawat, Pankaj. 2018. The New Global Road Map: Enduring Strategies for Turbulent Times. Brighton: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giacalone, Robert A., and Donald T. Wargo. 2009. The roots of the global financial crisis are in our business schools. Journal of Business Ethics Education 6: 147–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Robert Aaron, and James Edwin Howell. 1959. Higher education for business. The Journal of Business Education 35: 115–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, Mauro F., and Esteban García-Canal. 2009. The American model of the multinational firm and the new multinationals from emerging economies. Academy of Management Perspectives 23: 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtbrügge, Dirk, and Heidi Kreppel. 2012. Determinants of outward foreign direct investment from BRIC countries: an explorative study. International Journal of Emerging Markets 7: 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Thomas, and Eric Cornuel. 2012. Business schools in transition? Issues of impact, legitimacy, capabilities and re-invention. The Journal of Management Development 31: 329–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidan, Mansour, and Mary B. Teagarden. 2011. Conceptualizing and measuring global mindset. In Advances in Global Leadership. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, David Chan-oong. 2007. China Rising: Peace, Power, and Order in East Asia. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, David M. 2003. The American People in the Great Depression: Freedom from Fear, Part One. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, Tarun, and Krishna Palepu. 2000. The future of business groups in emerging markets: Long-run evidence from Chile. Academy of Management Journal 43: 268–85. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, Tarun, and Krishna G. Palepu. 2005. Spotting Institutional Voids in Emerging Markets. Boston: Harvard Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, Tarun, and Krishna G. Palepu. 2010. Winning in Emerging Markets: A Road Map for Strategy and Execution. Brighton: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, Tarun, and Jan W. Rivkin. 2001. Estimating the performance effects of business groups in emerging markets. Strategic Management Journal 22: 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Henry W., Martha Maznevski, Joerg Deetz, and Joseph DiStefano. 2009. International Management Behavior: Leading with a Global Mindset. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- London, Ted, and Stuart L. Hart. 2004. Reinventing strategies for emerging markets: Beyond the transnational model. Journal of International Business Studies 35: 350–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, Angus. 2007. The World Economy Volume 1: A Millennial Perspective Volume 2: Historical Statistics. New Delhi: Academic Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Mensi, Walid, Shawkat Hammoudeh, Duc Khuong Nguyen, and Sang Hoon Kang. 2016. Global financial crisis and spillover effects among the US and BRICS stock markets. International Review of Economics & Finance 42: 257–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mensi, Walid, Shawkat Hammoudeh, and Sang Hoon Kang. 2017. Dynamic linkages between developed and BRICS stock markets: Portfolio risk analysis. Finance Research Letters 21: 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudambi, Ram. 2018. Knowledge-intensive intangibles, spatial transaction costs, and the rise of populism. Journal of International Business Policy 1: 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Neill, Jim. 2001. Building Better Global Economic BRICs. New York: Goldman Sachs. [Google Scholar]

- Pandit, Vishwanath. 2018. Global Economic Crisis 2008: A Contemporary Reappraisal with an Ethical Perspective. New York: Goldman Sachs. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, Jeffrey, and Christina T. Fong. 2002. The End of Business Schools? Less Success Than Meets the Eye. Academy of Management Learning & Education 1: 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, Frank C. 1959. The education of American businessmen. The Journal of Business Education 35: 114–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Michael E., and Mark R. Kramer. 2011. The Big Idea: Creating Shared Value. Boston: Harvard Business Review. [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurti, Ravi. 2012. What is really different about emerging market multinationals? Global Strategy Journal 2: 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugman, Alan. 2012. The End of Globalization. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegelmilch, Bodo B., and Thomas Howard. 2011. The MBA in 2020: Will there still be one? The Journal of Management Development 30: 474–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Simon. 2017. Fermat’s Enigma: The Epic Quest to Solve the World’s Greatest Mathematical Problem. New York: Anchor. [Google Scholar]

- Skapinker, Michael. 2008. Why business ignores the business schools. Financial Times, June 8. [Google Scholar]

- Skapinker, Michael. 2011. Why business still ignores business schools. Financial Times, January 24. [Google Scholar]

- White, Lawrence J. 2002. Trends in aggregate concentration in the United States. Journal of Economic Perspectives 16: 137–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Dominic, and Roopa Purushothaman. 2003. Dreaming with BRICs: The path to 2050. Global Economics Paper, October 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Mike, Igor Filatotchev, Robert E. Hoskisson, and Mike W. Peng. 2005. Strategy research in emerging economies: Challenging the conventional wisdom. Journal of Management Studies 42: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, Gregory. 2010. The Greatest Trade Ever: The Behind-the-Scenes Story of How John Paulson Defied Wall Street and Made Financial History. New York: Crown Pub. [Google Scholar]

| 1. | |

| 2. | |

| 3. | Definition: “a business group is a set of firms which, though legally independent, are bound together by a constellation of formal and informal ties and are accustomed to taking coordinated action” (Khanna and Rivkin 2001, pp. 47–48). |

| 4. | (1) Firms from developed economies entering emerging economies, (2) domestic firms competing within emerging economies, (3) firms from emerging economies entering other emerging economies, (4) firms from emerging economies entering developed economies” (Wright et al. 2005, p. 1). |

| 5. | Institutional theory, transaction cost theory, resource-based theory, and agency theory (Wright et al. 2005, p. 1). |

| 6. | The author obtained his NASD Commodity Futures (Series 3) trading license in 2003. He is trilingual and well-traveled. He has visited the BRICS at least once, except for Brazil and has lived and worked in four different developed countries. He has been teaching economics and business courses to undergraduate and graduate students since 2002 (e.g., principles of macro- and micro economics, strategic management, international marketing, global strategy) in the US and in Europe. He has published his expertise in several academic journals, as well as in the specialized press (e.g., Les Echos and the Financial Times). He is the recipient of several corporate, teaching, and service awards. Whereas his international business background is quite extensive, it must be noted that the researcher has natural biases. |

| 7. | |

| 8. | |

| 9. | |

| 10. | |

| 11. | |

| 12. | |

| 13. | |

| 14. | |

| 15. | |

| 16. | |

| 17. | |

| 18. | |

| 19. | |

| 20. | |

| 21. | |

| 22. | |

| 23. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guillotin, B. Using Unconventional Wisdom to Re-Assess and Rebuild the BRICS. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2019, 12, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12010008

Guillotin B. Using Unconventional Wisdom to Re-Assess and Rebuild the BRICS. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2019; 12(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuillotin, Bertrand. 2019. "Using Unconventional Wisdom to Re-Assess and Rebuild the BRICS" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12010008

APA StyleGuillotin, B. (2019). Using Unconventional Wisdom to Re-Assess and Rebuild the BRICS. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12010008