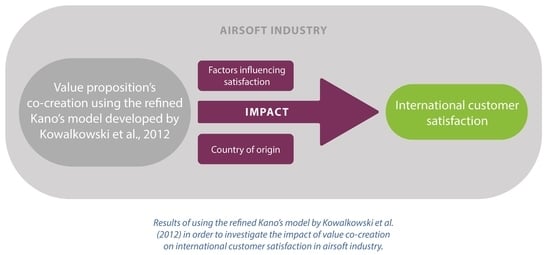

Impact of Value Co-Creation on International Customer Satisfaction in the Airsoft Industry: Does Country of Origin Matter?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Essence of Value and Value Propositions

2.2. Delivered Value and Customer Satisfaction

2.3. Value Proposition Creation and Co-Creation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Background

3.2. Sample and Sources of Data

3.3. Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- 1.

- Country.

- 2.

- Age.

- (a)

- <18.

- (b)

- 19–25.

- (c)

- 26–30.

- (d)

- 31–40.

- (e)

- 41<.

- 3.

- Gender.

- (a)

- Male.

- (b)

- Female.

- 4.

- Education.

- (a)

- Secondary.

- (b)

- Higher (post-secondary).

- (c)

- Doctoral.

- 5.

- Salary (monthly in USD).

- (a)

- <$500.

- (b)

- $501–$1000.

- (c)

- $1001–$2500.

- (d)

- $2501–$3999.

- (e)

- $4000–$5999.

- (f)

- $6000<.

- 6.

- How much do you spend on airsoft hobby (yearly in USD):

- (a)

- <$500.

- (b)

- $501–$1500.

- (c)

- $1501–$3000.

- (d)

- $3001–$5000.

- (e)

- $5000<.

- 7.

- How often do you play airsoft:

- (a)

- Less than once a month.

- (b)

- 1–2 times per month.

- (c)

- 3–5 times per month.

- (d)

- 6–8 times per month.

- (e)

- More than 9 times per month.

- 8.

- Which of the GATE products do you have experience with?

- (a)

- TITAN.

- (b)

- WARFET.

- (c)

- NanoHARD.

- (d)

- PicoAAB.

- (e)

- NanoAAB.

- (f)

- NanoASR.

- (g)

- MERF 3.2.

- (h)

- NanoSSR.

- (i)

- PicoSSR 3.

- (j)

- None.

- 9.

- Rate the product attributes (1—unnecessary, 2—not so important, 3—important, 4—necessary, 5—extremely necessary).

- Trigger sensitivity adjustment.

- Configurable fire selector.

- Non-adjustable pre-cocking.

- Adjustable pre-cocking.

- 3-rd burst.

- Configurable burst (two to 10 rounds).

- Rate of fire reduction.

- Decreasing wear and tear of Airsoft Electric Gun (AEG) internal parts.

- Setting delay between each semishots to simulate the delay from reload or recoil.

- Two stage trigger [AUG (germ. Armee Universal Gewehr-”universal army rifle”) Mode].

- ‘MOSFET’ reliability (internal protections).

- Low battery warning.

- Prolonging the lifespan of the motor.

- Diagnostic trouble codes.

- Resistance to atmospheric conditions.

- Resistance to water immersion.

- Built-in deans-t connectors.

- Included Mini-tamiya adapter.

- Compatibility with 14.8V lithium polymer (LI-PO) batteries.

- Complete wiring with trigger contacts.

- Functions adjustment via button and LED display.

- Functions adjustment via USB-Link and computer app.

- Functions adjustment via programmer (programming card).

- 10.

- Rate each of the following MOSFET improvements according to your needs (1- unnecessary, 2- not so important, 3-important, 4-necessary, 5-extremely necessary).

- In case of incorrectly connecting positive and negative battery terminals (reverse polarity), the MOSFET, motor and installation will be protected against damage.

- Functions adjustment via Bluetooth and smartphone app.

- Bolt-catch function (if there is no airsoft pellets (BBs) in your magazine, your AEG cannot fire a shot).

- The BBs counter (you exactly know how many BBs are currently in your magazine).

- 11.

- Do you think the GATE TITAN manual is detailed enough? Please skip the question if you did not see the TITAN manual.

- 12.

- Rate the types of manuals according to your preferences.

- Written manuals (1—I dislike written manuals; 5—I like written manuals).

- Tutorial videos (1—I never watch tutorial videos; 5—I always watch tutorial videos).

- Printed quickstart in product kit is. (1—unnecessary; 5—extremely necessary).

- 13.

- Taking into consideration the product quality, functions, features and reliability, is the price of TITAN Complete Set adequate to the product value?

- (a)

- YES, the price is adequate.

- (b)

- NO, the price is too high.

- (c)

- I am happy I can pay less, but I think that so advanced product would cost more.

- (d)

- I do not know the TITAN product.

- 14.

- What do you think would be the most fair price for TITAN Complete Set? (Please skip this question if you do not know the TITAN product).

- 15.

- How big a factor is price in your decision-making process? (1—price is not important for me; 5—price is extremely important for me).

- 16.

- Finish the sentence: I would like to.

- (a)

- pay higher price and have more advanced drop-in MOSFET with many functions.

- (b)

- pay less and have a simple version of drop-in MOSFET.

- 17.

- How does GATE rate in terms of price? (1—cheap taking into consideration quality, 5—very expensive).

- 18.

- Do you trust in GATE brand and GATE company? (1—I do not trust GATE, 5—I totally trust GATE).

- 19.

- Rate the risks that you may perceive when choosing GATE company (1—no risk, 2—low risk, 3—moderate risk, 4—high risk, 5—very high risk).

- Installation concerns.

- Product failure.

- Difficult product usage.

- Lack of technical support.

- 20.

- What do you consider a substitute for GATE product?

- 21.

- Airsoft.

- 22.

- What trends do you see coming in airsoft?

- 23.

- What irritates you as an airsofter?

- 24.

- Rate the factors influencing how much fun you have playing airsoft (1—not important, 5—extremely important).

- Realism.

- Airsoft field.

- Friends.

- Weather.

- Airsoft gun.

- Equipment.

- Fairness.

- 25.

- Rate the attributes of airsoft gun (1—not important, 5—extremely important).

- Range (Feet per second—FPS).

- Rate of fire.

- Trigger response.

- Option to adjust AEG with advanced MOSFET.

- 26.

- Why do you play airsoft? Rate reasons according to the level of impact on your decision to play airsoft. (—low impact, 5—high impact).

- To get entertained.

- For training.

- To show off.

- Because airsoft is a better alternative to FPS games.

- To check myself.

- To compete.

- 27.

- Had you liked FPS games before you started playing airsoft? (1—I hadn’t liked FPS games before started playing airsoft, 5—I had loved playing FPS before started playing airsoft).

- 28.

- Rate each of the elements according to the importance (1—not important, 5—extremely important).

- Brand name.

- Product functionality.

- Quality level.

- Packaging.

- Design (how the product looks like).

- Warranty period.

- After-sales service.

- Manuals (user-friendly and multilingual).

- Company website.

- Tutorial videos.

- Ease of installation.

- Promotions and advertising (e.g., discounts at online store).

References

- Acocella, Angela, and Feng Zhu. 2017. X Fire Paintball & Airsoft: Is Amazon a Friend or Foe (A)? Harvard Business School Cases 617: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, Amit Kumar, and Zillur Rahman. 2015. Roles and resource contributions of customers in value co-creation. International Strategic Management Review 3: 144–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aitken, Alan, and Robert Paton. 2016. Professional buyers and the value proposition. European Management Journal 34: 223–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akaka, Melissa Archpru, and Stephen L. Vargo. 2014. Technology as an operant resource in service (eco) systems. Information Systems and e-Business Management 12: 367–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, Maryam, and Dorothy E. Leidner. 2001. Review: Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Quarterly 25: 107–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, Cristina Elena. 2013. Stereotypical Factors in Tourism. Cross-Cultural Management Journal 15: 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Alshanty, Abdallah Mohammad Alshanty, and Okechukwu Lawrence Emeagwali. 2019. Market-sensing capability, knowledge creation and innovation: The moderating role of entrepreneurial-orientation. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 4: 171–78. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, James C., Dipak C. Jam, and Pradeep K. Chintagunta. 1993. Customer value assessment in business markets: A state-of-practice study. Journal of Business to Business Marketing 1: 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyte, Jurate, and Aiste Dovaliene. 2014. Relations between customer engagement into value creation and customer loyalty. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 156: 484–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barnes, Cindy, Helen Blake, and David Pinder. 2009. Creating and delivering your value proposition: Managing customer experience for profit. In Creating and Delivering Your Value Proposition: Managing Customer Experience for Profit. Edited by Cindy Barnes, Helen Blake and David Pinder. Philadelphia: Kogan Page Ltd., pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Berawi, Mohammed Ali, and Roy Woodhead. 2020. Value Creation and the Pursuit of Multi Factor Productivity Improvement. International Journal of Technology 11: 111–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bower, Marvin, and Robert A. Garda. 1985. The role of marketing in management. The McKinsey Quarterly 3: 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, Cliff, and Veronique Ambrosini. 2000. Value creation versus value capture: Towards a coherent definition of value in strategy. British Journal of Management 11: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, Byrl. 1975. Real Estate Appraisal Terminology. In Real Estate Appraisal Terminology. Edited by Byrl Boyce. Chicago: American Institute of Real Estate Appraisers and the Society of Real Estate Appraisers, p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Breidbach, Christoph F., and Paul P. Maglio. 2016. Technology-enabled value co-creation: An empirical analysis of actors, resources, and practices. Industrial Marketing Management 56: 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Jo, Amanda Broderick, and Nick Lee. 2007. Word of mouth communication within online communities: Conceptualizing the online social network. Journal of Interactive Marketing 21: 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camlek, Victor. 2010. How to spot a real value proposition. Information Services & Use 30: 119–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chatain, Olivier. 2011. Value creation, competition, and performance in buyer—supplier relationships. Strategic Management Journal 32: 76–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, David, Christopher Gan, Hua Hwa Au Yong, and Esther Choong. 2006. Customer satisfaction: A study of bank customer retention in New Zealand. Discussion Paper: Lincoln University Catenbury 109: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cossío-Silva, Francisco José, María Ángeles Revilla-Camacho, Manuela Vega-Vázquez, and Beatriz Palacios-Florencio. 2016. Value co-creation and customer loyalty. Journal of Business Research 69: 1621–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, Jeffrey G., Robert P. Garrett, Donald F. Kuratko, and Dean A. Shepherd. 2015. Value proposition evolution and the performance of internal corporate ventures. Journal of Business Venturing 30: 749–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, James A., Matthias Menter, and Conor O’Kane. 2018. Value creation in the quadruple helix: A micro level conceptual model of principal investigators as value creators. R&D Management 48: 136–47. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, Thomas H., and Laurence Prusak. 1998. Working knowledge: How organizations manage what they know. In Working knowledge: How Organizations Manage what they Know. Edited by Thomas H. Davenport and Laurence Prusak. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davila, Tony. 2000. An empirical study on the drivers of management control systems design in new product development. Accounting, Organizations and Society 25: 383–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Qi. 2019. Blockchain Economical Models, Delegated Proof of Economic Value and Delegated Adaptive Byzantine Fault Tolerance and their implementation in Artificial Intelligence BlockCloud. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12: 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Do Duc, Linh, Vladimir Horák, Tomas Lukáč, Roman Vítek, and Quang Huy Mai. 2016. Dynamics of knock-open valve for gas guns powered by carbon dioxide. Proceedings of the Scientific Conference AFASES 1: 323–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dyduch, Wojciech. 2019. Entrepreneurial Strategy Stimulating Value Creation: Conceptual Findings and Some Empirical Tests. Entrepreneurial Business & Economics Review 7: 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Etgar, Michael. 2008. A descriptive model of the consumer co-production process. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 36: 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, Claes. 1992. A national customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. Journal of Marketing 56: 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Frow, Pennie, and Adrian Payne. 2011. A stakeholder perspective of the value proposition concept. European Journal of Marketing 45: 223–40. [Google Scholar]

- Frow, Pennie, and Adrian Payne. 2014. Developing superior value propositions: A strategic marketing imperative. Journal of Service Management 25: 213–27. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, Craig S., Sanford Ehrlich, and Alex DeNoble. 2006. Predicting technology success: Identifying Key predictors and assessing expert evaluation for advanced technologies. The Journal of Technology Transfer 31: 673–84. [Google Scholar]

- Galvagno, Marco, and Daniele Dalli. 2014. Theory of value co-creation: A systematic literature review. Managing Service Quality 24: 643–83. [Google Scholar]

- Giese, Joan L., and Joseph A. Cote. 2000. Defining consumer satisfaction. Academy of Marketing Science Review 1: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Goedhart, Marc, Tim Koller, and David Wessels. 2015. Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies. In Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies. Edited by Marc Goedhart, Tim Koller and David Wessels. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Rob. 2006. Social, environmental and sustainability reporting and organisational value creation? Whose value? Whose creation? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 19: 793–819. [Google Scholar]

- Groen, Aard, Gary Cook, and Peter Van der Sijde. 2015. New technology-based firms in the new millennium. In New Technology-Based Firms in the New Millennium. Edited by Aard Groen, Gary Cook and Peter Van der Sijde. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gronroos, Christian, and Paivi Voima. 2013. Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and Co-creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 41: 133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guesalaga, Rodrigo, Daiane Scaraboto, and Meghan Pierce. 2016. Cultural influences on expectations and evaluations of service quality in emerging markets. International Marketing Review 33: 88–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Sunil, and Donald Lehman. 2005. Managing Customers as Investments. Chennai: Pearson Education India, vol. 28, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Haavisto, Anna-Kaisa, Ahmad Sahraravand, Paivi Puska, and Tiina Leivo. 2019. Toy gun eye injuries—Eye protection needed Helsinki ocular trauma study. Acta Ophthalmologica 97: 430–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hareli, Shlomo, and Ursula Hess. 2012. The social signal value of emotions. Cognition & Emotion 26: 385–89. [Google Scholar]

- He, Ying, and Dawei Zhang. 2019. Manager’s Characteristics, Debt Financing and Firm Value. China Economist 14: 96–110. [Google Scholar]

- Horák, Vladimir, Linh Duc, Roman Vítek, S. Beer, and Quang Huy Mai. 2014. Prediction of the air gun performance. Advances in Military Technology 9: 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Nicholas. 2011. Marx’s theory of price and its modern rivals. In Marx’s Theory of Price and Its Modern Rivals. Edited by Nicholas Howard. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Jung Kuei, and Yi Ching Hsieh. 2015. Dialogic co-creation and service innovation performance in high-tech companies. Journal of Business Research 68: 2266–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaki, Andrzej, and Barbara Siuta-Tokarska. 2019. New imperative of corporate value creation in face of the challenges of sustainable development. Entrepreneurial Business & Economics Review 7: 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jean, Ruey-Jer (Bryan), Rudolf R. Sinkovics, and S. Tamer Cavusgil. 2010. Enhancing International Customer-Supplier Relationships through IT Resources: A Study of Taiwanese Electronics Suppliers. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 1218–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Adekannbi, and Aje Mo. 2018. Factors influencing customer satisfaction and loyalty to internet banking services among undergraduates of a Nigerian University. The Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce 23: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kambil, Ajit, Ari Ginsberg, and Michael Bloch. 1996. Re-Inventing Value Propositions. Working Paper no. 2451/14205. New York: New York University. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. 2004. Strategy maps: Converting intangible assets into tangible outcomes. In Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes. Edited by Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton. Boston: Harvard Business Press, p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kelty, Logan. 2013. Let’s Make a Deal: The Exchange Value of Advertising. International Journal of Integrated Marketing Communications 5: 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, Eric, Paul Bierly, and Shanthi Gopalakrishnan. 2001. Vasa syndrome: Insights from a 17th-century new-product disaster. Academy of Management Executive 15: 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Muhammad Asad. 2019. The Perception of the Customers toward Social Media Marketing: Evidence from Local and International Media Users. Journal of Managerial Sciences 13: 117–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalkowski, Christian, Oscar P. Ridell, Jimmie G. Röndell, and David Sörhammar. 2012. The co-creative practice of forming a value proposition. Journal of Marketing Management 28: 1553–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanning, Michaels, and Edward Michaels. 1988. A business is a value delivery system. McKinsey Staff Paper 41: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lanning, Michael. 1998. Delivering Profitable Value. In Delivering Profitable Value. Edited by Michael Lanning. Cambridge: Perseus Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lepak, David P., Ken G. Smith, and M. Susan Taylor. 2007. Value creation and value capture: A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Review 32: 180–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lerro, Antonio. 2011. A stakeholder-based perspective in the value impact assessment of the project valuing intangible assets in Scottish renewable SMEs. Measuring Business Excellence 15: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, Michael G., K. Scott Swan, and Marielle E. H. Creusen. 2016. Perspective: A review of marketing research on product design with directions for future research. Journal of Product Innovation Management 33: 320–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, Ashley. 2017. Advancing airguns & airsoft sales. Shooting Industry 50: 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Menguc, Bulent, Seigyoung Auh, and Peter Yannopoulos. 2014. Customer and supplier involvement in design: The moderating role of incremental and radical innovation capability. Journal of Product Innovation Management 31: 313–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, Gabriela Maria, Mateus Jonny Rodrigues, Janaina de Moura Engracia Giraldi, and Marcos Fava Neves. 2018. Country of origin effect: A study with Brazilian consumers in the luxury market. Brazilian Business Review (English Edition) 15: 348–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Michael, Minet Schindehutte, and Jeffrey Allen. 2005. The entrepreneur’s business model: Toward a unified perspective. Journal of Business Research 58: 726–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi-Tavani, Zhaleh, Sahar Mousavi, Ghasen Zaefarian, and Peter Naudé. 2020. Relationship learning and international customer involvement in new product design: The moderating roles of customer dependence and cultural distance. Journal of Business Research 120: 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, Jackson, Brian S. Silverman, and Todd R. Zenger. 2007. The problem of creating and capturing value. Strategic Organisation 5: 211–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, Ikujiro, and Hirotaka Takeuchi. 1995. The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. In The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. Edited by Ikujiro Nonaka and Hirotaka Takeuchi. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier, Richard L. 1980. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research 17: 460–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, Alex, Yves Pigneur, Greg Bernarda, and Alan Smith. 2014. Value Proposition Design. In Value Proposition Design. Edited by Alex Osterwalder, Yves Pigneur, Greg Bernarda and Alan Smith. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Pattarakitham, Amornrat. 2015. The Factors Influence Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty: A Study of Tea Beverage in Bangkok. Paper presented at the XIV International Business and Economy Conference (IBEC), Bangkok, Thailand, January 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Adrian, and Sue Holt. 2001. Diagnosing customer value: Integrating the value process and relationship marketing. British Journal of Management 12: 159–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta-Olearnik, Mirosława. 2016. Marketing Communication in the Process of University Internationalisation. Handel Wewnętrzny 3: 266–75. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, Coimbatore Krishnarao, and Venkatram Ramaswamy. 2000. Co-opting customer competence. Harvard Business Review 78: 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, Coimbatore Krishnarao, and Venkatram Ramaswamy. 2004. Co-creating unique value with customers. Strategy & Leadership 32: 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, Coimbatore Krishnarao, and Venkatram Ramaswamy. 2013. The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers. In The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers. Edited by Coimbatore Krishnarao Prahalad and Venkatram Ramaswamy. Boston: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Priem, Richard L. 2007. A consumer perspective on value creation. Academy of Management Review 32: 219–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riihimäki, Tapio, Valtteri Kaartemo, and Peter Zettinig. 2016. Co-evolution of dynamic capabilities and value propositions from a process perspective. Advances in Business-Related Scientific Research Journal 7: 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Roşu, Daniel. 2015. Participants Profile in Airsoft Sport. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 180: 1316–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rozian Sanib, Noor Izza, Yuhaniz Abdul Aziz, Zaiton Samdin, and Khalid Ab Rahim. 2013. Comparison of Marketing Mix Dimensions between Local and International Hotel Customers in Malaysia. International Journal of Economics & Management 7: 297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, Victor, Venkatesh Mani, and Praveen Goyal. 2020. Emerging trends in the literature of value co-creation: A bibliometric analysis. Benchmarking: An International Journal 27: 981–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, Raquel, and M. Ángeles Iniesta-Bonillo. 2007. The concept of perceived value: A systematic review of the research. Marketing Theory 7: 427–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunte, Jon Peiter, and Mads Egil Saunte. 2006. 33 cases of airsoft gun pellet ocular injuries in Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998–2002. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica 84: 755–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunte, Jon Peiter, and Mads Egil Saunte. 2008. Childhood ocular trauma in the Copenhagen area from 1998 to 2003: Eye injuries caused by airsoft guns are twice as common as firework-related injuries. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica 86: 345–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scridon, Mircea Andrei, Sorin Adrian Achim, Mirela-Oana Pintea, and Marius Dan Gavriletea. 2019. Risk and perceived value: Antecedents of customer satisfaction and loyalty in a sustainable business model. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 32: 909–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seger-Guttmann, Tali, Iris Vilnai-Yavetz, and Mark S. Rosenbaum. 2017. Disparate satisfaction scores? Consider your customer’s country-of-origin: A case study. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 27: 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servera-Francés, David, and Lidia Piqueras-Tomás. 2019. The effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer loyalty through consumer perceived value. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 32: 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sevanandee, Brenda, and Adjnu Damar-Lakadoo. 2018. Country-of-Origin Effects on Consumer Buying Behaviours. A Case of Mobile Phones. Studies in Business & Economics 13: 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Sideri, Katerina, and Andreas Panagopoulos. 2018. Setting up a Technology Commercialization Office at a Non-entrepreneurial University: An Insider’s Look at Practices and Culture. Journal of Technology Transfer 43: 953–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamidass, Paul M. 2012. University startups as a commercialization alternative: Lessons from three contrasting case studies. The Journal of Technology Transfer 38: 788–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szarucki, Marek, and Gabriela Menet. 2018. Service marketing, value co-creation and customer satisfaction in the airsoft industry: Case of a technology-based firm. Business, Management and Education 16: 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, Carmen, Antonie van Rensburg, and Cornelius Stephanus L. Schutte. 2015. An engineering approach to an integrated value proposition design framework. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering 26: 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vargo, Stephen L., and Robert F. Lusch. 2004. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing 68: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Chen-Ya, Li Miao, and Anna S. Mattila. 2015. Customer responses to intercultural communication accommodation strategies in hospitality service encounters. International Journal of Hospitality Management 51: 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiaobei, Goran Persson, and Lars Huemer. 2016. Logistics service providers and value creation through collaboration: A case study. Long Range Planning 49: 117–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, Robert. 1997. Customer Value The Next Source of Competitive Advantage. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 25: 139–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, Marc, and Markus A. Kirchberger. 2015. Customer value propositions as inter-organizational management accounting to support customer collaboration. Industrial Marketing Management 46: 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Ching-Chow, and Dylan Sung. 2011. An integrated model of value creation based on the refined Kano’s model and the Blue Ocean strategy. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 22: 925–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Ching-Chow, Ping-Shun Chen, and Yu-Hui Chien. 2014. Customer expertise, affective commitment, customer participation, and loyalty in B&B services. International Journal of Organizational Innovation 6: 174–83. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Ching-Chow. 2005. The Refined Kano’s Model and its Application. Total Quality Management 16: 1127–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

| Measures | Arithmetic Average | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Lower Quartile | Median | Upper Quartile | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | ||||||||

| Brand name | 3.17 | 1.20 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Product functionality | 4.76 | 0.46 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Quality level | 4.83 | 0.40 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Packaging | 2.93 | 1.27 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Design | 3.69 | 1.06 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Warranty period | 4.03 | 1.11 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| After-sales service | 4.29 | 0.85 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Manuals | 4.04 | 0.92 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Company website | 4.02 | 0.97 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Tutorial videos | 4.06 | 1.01 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Ease of installation | 4.21 | 0.92 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Price | 3.70 | 0.96 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Promotions and advertising | 3.99 | 1.12 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Arithmetic Average | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Lower Quartile | Median | Upper Quartile | Maximum | Kruskal–Wallis’s Test | POST-HOC (Dunn–Bonferroni) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | EU | N. America | Other | ||||||||||

| Brand name | Asia | 3.33 | 1.18 | 1 | 3.00 | 3 | 4.00 | 5 | H = 0.74 p = 0.86 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EU | 3.12 | 1.19 | 1 | 2.00 | 3 | 4.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| N. America | 3.24 | 1.20 | 1 | 2.25 | 3 | 4.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Other | 3.25 | 1.58 | 1 | 2.50 | 3.5 | 4.25 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Product functionality | Asia | 4.73 | 0.46 | 4 | 4.50 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | H = 4.46 p = 0.22 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EU | 4.74 | 0.50 | 3 | 5.00 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 0.46 | 1 | |||

| N. America | 4.89 | 0.31 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 0.46 | 0.61 | |||

| Other | 4.63 | 0.52 | 4 | 4.00 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.61 | |||

| Quality level | Asia | 4.93 | 0.26 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | H = 2.67 p = 0.45 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EU | 4.79 | 0.45 | 3 | 5.00 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| N. America | 4.89 | 0.31 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Other | 4.88 | 0.35 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Packaging | Asia | 3.27 | 1.03 | 1 | 3.00 | 3 | 4.00 | 5 | H = 4.38 p = 0.22 | 1 | 1 | 0.23 | |

| EU | 2.93 | 1.30 | 1 | 2.00 | 3 | 4.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.52 | |||

| N. America | 2.97 | 1.26 | 1 | 2.00 | 3 | 4.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.56 | |||

| Other | 2.13 | 1.25 | 1 | 1.00 | 2 | 2.50 | 4 | 0.23 | 0.52 | 0.56 | |||

| Design (how the product looks like) | Asia | 4.07 | 0.96 | 2 | 3.50 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | H= 2.68 p = 0.44 | 0.81 | 1 | 1 | |

| EU | 3.63 | 1.07 | 1 | 3.00 | 4 | 4.00 | 5 | 0.81 | 1 | 1 | |||

| N. America | 3.76 | 1.02 | 1 | 3.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Other | 3.38 | 1.30 | 1 | 2.75 | 4 | 4.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Warranty period | Asia | 4.33 | 0.98 | 2 | 4.00 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | H = 2.75 p = 0.43 | 1 | 1 | 0.94 | |

| EU | 4.08 | 1.07 | 1 | 3.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| N. America | 3.84 | 1.28 | 1 | 3.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Other | 3.75 | 1.04 | 2 | 3.00 | 4 | 4.25 | 5 | 0.94 | 1 | 1 | |||

| After-sales service | Asia | 4.47 | 0.74 | 3 | 4.00 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | H = 0.85 p = 0.84 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EU | 4.29 | 0.84 | 1 | 4.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| N. America | 4.24 | 0.94 | 1 | 4.00 | 4.5 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Other | 4.25 | 0.71 | 3 | 4.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Manuals (user-friendly and multilingual) | Asia | 4.53 | 0.74 | 3 | 4.00 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | H = 5.90 p = 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.45 | |

| EU | 4.06 | 0.83 | 2 | 4.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 0.22 | 1 | 1 | |||

| N. America | 3.84 | 1.15 | 1 | 3.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 0.13 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Other | 3.88 | 0.99 | 3 | 3.00 | 3.5 | 5.00 | 5 | 0.45 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Company website | Asia | 4.20 | 0.77 | 3 | 4.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | H = 1.06 p = 0.79 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EU | 3.97 | 1.00 | 1 | 3.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| N. America | 4.11 | 0.98 | 2 | 3.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Other | 3.88 | 0.99 | 2 | 3.75 | 4 | 4.25 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Tutorial videos | Asia | 4.40 | 0.83 | 3 | 4.00 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | H = 5.93 p = 0.12 | 1 | 1 | 0.11 | |

| EU | 4.08 | 1.04 | 1 | 3.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.26 | |||

| N. America | 4.00 | 0.99 | 2 | 3.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.61 | |||

| Other | 3.38 | 0.92 | 2 | 3.00 | 3 | 4.00 | 5 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.61 | |||

| Ease of installation | Asia | 4.73 | 0.46 | 4 | 4.50 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | H = 6.85 p = 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.41 | |

| EU | 4.23 | 0.86 | 2 | 4.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 0.21 | 1 | 1 | |||

| N. America | 3.97 | 1.13 | 1 | 3.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 0.07 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Other | 4.00 | 1.07 | 2 | 3.75 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 0.41 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Price | Asia | 3.47 | 1.13 | 1 | 3.00 | 3 | 4.00 | 5 | H = 3.62 p = 0.31 | 1 | 0.73 | 1 | |

| EU | 3.65 | 0.96 | 1 | 3.00 | 4 | 4.00 | 5 | 1 | 0.54 | 1 | |||

| N. America | 3.95 | 0.93 | 2 | 3.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 0.73 | 0.54 | 1 | |||

| Other | 3.75 | 0.71 | 3 | 3.00 | 4 | 4.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Promotions and advertising | Asia | 4.20 | 1.01 | 2 | 3.50 | 5 | 5.00 | 5 | H = 1.54 p = 0.67 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EU | 4.03 | 1.07 | 1 | 3.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| N. America | 3.89 | 1.23 | 1 | 3.00 | 4 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Other | 3.50 | 1.51 | 1 | 2.75 | 3.5 | 5.00 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Menet, G.; Szarucki, M. Impact of Value Co-Creation on International Customer Satisfaction in the Airsoft Industry: Does Country of Origin Matter? J. Risk Financial Manag. 2020, 13, 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13100223

Menet G, Szarucki M. Impact of Value Co-Creation on International Customer Satisfaction in the Airsoft Industry: Does Country of Origin Matter? Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2020; 13(10):223. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13100223

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenet, Gabriela, and Marek Szarucki. 2020. "Impact of Value Co-Creation on International Customer Satisfaction in the Airsoft Industry: Does Country of Origin Matter?" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13, no. 10: 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13100223

APA StyleMenet, G., & Szarucki, M. (2020). Impact of Value Co-Creation on International Customer Satisfaction in the Airsoft Industry: Does Country of Origin Matter? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(10), 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13100223