1. Introduction

Crowdfunding is a digital innovation that has been hailed for its potential to address financing challenges (

World Bank Group and People’s Bank of China 2018;

European Commission 2018). In 2016, global crowdfunding volumes more than doubled compared to 2015, reaching more than

$290 billion USD. At the same time, crowdfunding volume continues to vary significantly between countries, with China, the U.S., and the UK exhibiting volumes per capita which are more than 15 times higher than the global average

1. Such heterogeneity in volumes explains why crowdfunding is not yet able to compete with traditional sources of financing in economic terms. It was 0.29% of the global stock of domestic credit at the end of 2016 and 0.43% of the global market value of publicly traded shares at the end of 2015

2. Still, there are examples of crowdfunding taking up a prominent role in financing. One such example can be found in the UK, where crowdfunding contributed nearly a third of all new loans to businesses with an annual turnover of less than £2 million GBP in 2017 (

Zhang et al. 2018). The fact that crowdfunding has become important only in certain markets raises the question, why has the adoption of crowdfunding been so uneven across countries?

With crowdfunding being both a digital innovation and an added layer of financing, previous research related to these fields may help to address this question. Within the field of digital innovations,

Hinings et al. (

2018) provide a formidable explanation on why institutional theory should be considered a linchpin for studying the development and spread of digital innovations. They argue that existing institutional arrangements are fundamental to laying the path for new ideas to emerge and disseminate, since these new ideas must first gain legitimacy from critical crowds to become socially accepted. According to institutional theory, institutions provide such legitimacy to social objects and act as vehicles for allocating society’s resources (

Ostrom 2008;

Parsons 1953;

Suchman 1995). The relevance of institutions in determining which objects become more socially acceptable and, therefore, more prominent, also features extensively in literature related to financing activities. The role of institutional factors (e.g., the market for corporate control, bankruptcy code and the tax code, type of financial system), has been also investigated in literature that focuses on the differences in financing patterns of firms across countries e.g., (

Rajan and Zingales 1995;

Demirgüç-Kunt and Maksimovic 1999;

Moritz et al. 2016). Several papers, such as

Demirgüç-Kunt and Levine (

2001),

Ergungor (

2004),

Aggarwal and Goodell (

2009) find empirical evidence that institutional factors may help explain differences in country-level preferences towards either market-based or bank-based financial intermediation models.

However, we cannot directly link the determinants of crowdfunding volumes to those found in previous literature. First,

La Porta et al. (

1998) argue that there is no use in distinguishing countries based on firm financing patterns, since market-based and bank-based systems can be complementary ways of financing, and effective institutions, such as a well-functioning legal system, should support both, allowing each to develop independently of the other. Similarly, literature related to crowdfunding highlights this phenomenon as a new and complementary form of financing (

Short et al. 2017;

Hervé and Schwienbacher 2018), which therefore should follow its own path of development. Second, as argued by

Ang and Kumar (

2014), the spread of financial innovation is not necessarily tied to any previous developments in a country’s financial system, but instead to the underlying institutional framework. They find that countries that are genetically more distant from frontier countries of innovation tend to be less capable of incorporating innovative ideas within their financial systems. As such, there seems to be little reason to limit ourselves to only those determinants that are associated with the spread of previous, unconnected financial developments.

Still, in connection with the previous literature, we argue that institutional theory as a whole also provides a rich framework for understanding the adoption of crowdfunding. First, as in the related literature on digital (financial) innovations and financial intermediation models e.g., (

Ang and Kumar 2014;

Hinings et al. 2018), we expect institutions to act as vehicles of legitimacy for this novel financial development. Therefore, institutional determinants should have significant power in explaining the heterogeneity in crowdfunding volumes between countries. Second, the role of institutions has been shown to lessen over time as innovations move towards general validation e.g., (

Johnson et al. 2006). Thus, the current development stage of crowdfunding provides suitable conditions to test why only some countries have become early adopters of crowdfunding, while others have shown only minute interest. Third, crowdfunding is associated with severe market imperfections, such as information asymmetry (

Belleflamme et al. 2014;

Kleinert et al. 2020;

Miglo 2020) and moral hazard (

Strausz 2017;

Chemla and Tinn 2020). Institutions may mitigate the risk associated with these imperfections by broadly inserting trust within the system (

Bergh et al. 2019). Finally,

Scott (

2014) emphasizes that while each institutional pillar—regulative, normative and cultural-cognitive—may act towards achieving the same goal, each employ their own mechanisms and may, at times, counteract each other. As such, it is possible for a country to have large crowdfunding volumes even if only one of the three pillars is supportive in providing legitimacy to crowdfunding. Because of this, it is important to consider the role of institutions from all three pillars.

Although

Kshetri (

2015,

2018) proposes a theoretical framework, based on institutional theory, to explain crowdfunding success, empirical research on crowdfunding has been inhibited by the highly fragmented nature of the crowdfunding industry and lack of common aggregate statistics. Accordingly, the majority of previous research has focused on data from one specific crowdfunding platform (for a review, see (

Gleasure and Feller 2016)). As an example,

Cumming et al. (

2017) view cleantech crowdfunding across 81 countries, with one of their hypotheses proposing that the prominence of cleantech crowdfunding campaigns is associated with certain cultural characteristics. While they do find that cleantech crowdfunding campaigns more frequently originate from countries with low levels of individualism, their data is limited to only those campaigns hosted on the platform Indiegogo, which is based in the U.S. As a result, more than 80 per cent of the campaigns examined originate from the U.S. and Canada, and all of the campaigns are strictly reward-based, due to the nature of the platform used. Alternatively,

Cumming et al. (

2019) use data from 93 different platforms and find that a regulative update carried out by Canadian provinces in early 2016 led to a better application of due diligence by platforms, which in turn was positively related to campaigns success and higher crowdfunding volumes. However, all of the platforms under consideration originated from Canada, thus significantly limiting the variation of the wider surrounding institutional framework that may affect crowdfunding volumes. Moving more towards a global approach,

Rossi et al. (

2018) use a survey to collect campaign data from 185 investment-based platforms spread across nine countries. As their aim is to focus on how certain platform-specific characteristics affect crowdfunding outcomes, they only include some institutional factors as country-level control variables, and do not record any statistically significant association for these variables when tested against money raised. Moreover, even though they consider platforms from multiple countries, they do not specifically aim to capture a representative sample of all crowdfunding volumes in each country. While this type of research helps understand crowdfunding as a phenomenon in specific settings, it does not provide a thorough explanation on how institutional factors affect crowdfunding on a global scale and for different types of crowdfunding.

To the best of our knowledge, there exist only two relevant papers focusing on the country-specific determinants of all types of crowdfunding on a global scale. First,

Dushnitsky et al. (

2016) investigate the determinants of crowdfunding platform creation. As they focus on the number of platforms, their study does not cover the actual crowdfunding volumes. Moreover, their coverage of institutional aspects is limited to only the regulative pillar, where they consider legal rights and crowdfunding-specific regulations to be important indicators, but find no significant association for the latter. In contrast to this result, the working paper by

Rau (

2018), which also focuses on how the legal framework of a country affects its crowdfunding volumes, finds that the introduction of explicit crowdfunding regulations does indeed provide a very robust link to crowdfunding volumes. As

Rau (

2018) considers the legal system to be especially important and does not rely on any firm theoretical foundation for the inclusion of other explanatory variables, he otherwise fails to take a broad range of potentially important institutional indicators into account. Consequently, the models employing crowdfunding volume as a dependent variable only control for, in select specifications, the generalized level of trust within a country as an additional institutional factor beside the introduction of explicit crowdfunding regulations. Compared to

Rau (

2018), we view the regulative aspects in much more detail, distinguishing between whether the crowdfunding-specific regulation targets only debt-based or equity based types of crowdfunding, and testing how these targeted regulations affect both the total crowdfunding volumes within a country, as well as the volumes of different types of crowdfunding. Furthermore, in contrast to both previous papers, we compare country-level crowdfunding volumes to a broad set of institutional factors, including a total of 12 institutional variables consistent with the theoretical framework of

Kshetri (

2015,

2018). Hence, our paper provides a comprehensive answer to each of

Kshetri’s (

2015,

2018) institutional theory based propositions, which have thus far been ignored in empirical research. While we use the same underlying data as

Rau (

2018), we collapse the annual data into average values instead of using a panel setup, since the institutional explanatory variables are unlikely to exhibit significant variation over the two year period observed.

The objective of this paper is to investigate how a wide range of institutional factors that may rely on different operating mechanisms contribute to the adoption of crowdfunding in different countries. We build on the theoretical framework proposed by

Kshetri (

2015,

2018) to formulate eight hypotheses. For testing the hypotheses, we use data on crowdfunding volumes gathered by the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF) for years 2015–2016. The sample covers 122 countries. Determinants of crowdfunding volumes are investigated using cross-sectional regression models.

We confirm that institutions highly targeted at crowdfunding, such as explicit regulation, seem to matter, but also show that a broad range of other regulative and cultural-cognitive institutions are important determinants of crowdfunding volumes. The results concerning the role of normative institutions remain rather inconclusive. We find that countries having crowdfunding-specific regulations, stronger legal rights, greater financial freedom, higher democracy levels, and stronger e-service culture have also tended to experience greater total crowdfunding volumes per capita. The most robust associations across different types of crowdfunding are observed for the presence of crowdfunding-specific regulations, with the economic association becoming stronger when the regulation is explicitly targeted at the corresponding type of crowdfunding, and e-service culture. Some of these institutions, such as crowdfunding-specific regulations, can be developed easily by policymakers. Others, such as e-service culture, are more difficult to influence, but are still important factors to consider. Over time, however, continuous use of crowdfunding in localized settings is likely to increase its acceptance and utilization on a global scale.

This paper contributes to two streams of literature. First, we add to the discussion of the role of institutions in providing legitimacy for the adoption of (digital) financial innovations (

Aggarwal and Goodell 2009;

Ang and Kumar 2014). Secondly, we provide much needed empirical evidence on the interlinkages between institutional structures in place and crowdfunding volumes hypothesized in

Kshetri (

2015,

2018). As such, the empirical results of this paper are important for policymakers, as they provide a pathway to developing institutions that could foster the growth of crowdfunding.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides a brief overview of institutional theory and discusses its implications on crowdfunding, following which we develop a set of hypotheses on how differing institutional structures in countries may affect crowdfunding volumes.

Section 3 discusses the data and methodology.

Section 4 presents the results of the empirical models and discusses the findings. Finally,

Section 5 concludes and discusses the contribution and limitations of this paper as well as the implications for policy considerations.

2. Hypothesis Development

A number of leading scholars in the field of new institutional economics e.g., (

North 1990;

Ostrom 2008;

Williamson 1991), have embraced the term “rules of the game” to describe the role of institutions in macroeconomic analysis.

North (

2008) defines institutions as a set of formal rules and informal norms, along with the manners in which either are enforced. Organizations, as economic agents, use their skills and strategies to act within the set of rules in order to win the game (

North 1990). Therefore, the success of organizations depends upon a combination of both the “rules of the game” and the set of attributes of each economic agent. As the institutional framework of the economy dictates the skillset that will lead to the greatest possible pay-off, the types of organizations that come into existence in a given economy ultimately reflect the payoff structure of the society (

North 2008).

The ability of the institutional framework to dictate which organizations thrive and which suffer can be traced back to a key concept of institutional theory: the need for legitimacy.

Suchman (

1995, p. 574) describes legitimacy as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions”. According to

Scott (

2014), the “socially constructed system” Suchman is referring to are the institutions. Although institutional factors alone cannot determine the outcomes, institutions act as structures that individuals use to allocate resources (

Ostrom 2008).

If the institutional theory were to hold for the development of crowdfunding, these concepts could potentially explain the vast heterogeneity of crowdfunding volumes between countries. When applying institutional theory on crowdfunding, we can view crowdfunding platforms as organizations with rather homogenous skillsets and targeted levels of performance. Platforms are then subjected to different “rules of the game” in various countries, thus resulting in differing levels of perceived legitimacy. In addition to institutional effects, platforms are also subject to different levels of resources, for instance, the level of traditional financial sector development, availability of funds, and general wealth of the population. The combination of these effects is expected to lead to heterogeneous crowdfunding volumes, even when platforms themselves operate in a similar fashion.

Institutions should also be more relevant for newly formed innovations, such as crowdfunding. According to

Johnson et al. (

2006) only those innovations that are in accordance with a local society’s widely accepted norms, values, and beliefs will find legitimacy and will, thereby, enter use. Once an innovation is locally validated in one society, it will also be more readily adopted elsewhere. Still, its adoption in other locations during the early stages of global diffusion will somewhat depend on how well the innovation conforms to each specific location’s widely accepted values. Eventually, the innovation will become widely accepted as part of the global status quo, framing the future actions of all societies. This implies that if crowdfunding were to become a prominent component of the financial system in at least some countries, further expansion into others would become less reliant on the local values and beliefs of those societies. The latter would hinder the ability of institutions to explain the success of crowdfunding.

Thus far, we have mostly used the term “institutions” to describe a set of rules that either inhibit negative or endorse positive behavior, as defined by society’s widely accepted values. However, there is no agreement amongst institutional theorists on the types of institutions that matter the most.

Scott (

2014) divides institutions into three pillars: regulative, cultural-cognitive, and normative. The regulative pillar is based on setting formal or informal rules, monitoring compliance, and sanctioning disobedience. The cultural-cognitive pillar refers to a collective, taken for granted, understanding of how objects should be interpreted within a society, shaped by deep-rooted cultural values. The normative pillar assumes that individuals comply because they feel it would be socially appropriate to do so, not because of the threat of sanctions.

Scott (

2014) argues that although the underlying elements for each of these pillars form a continuum, they are divergent concepts and need to be analyzed separately. This approach enables us to refrain from ruling out the effects of specific types of institutions prematurely but does mean that we must classify each hypothesis only under one specific pillar.

Kshetri (

2015,

2018) relied on

Scott’s (

2014) three-pillar handling of institutions to develop a theoretical framework on how institutional factors may affect to crowdfunding success. We build on his propositions to formulate eight testable hypotheses linking crowdfunding success with various indicators describing institutional structures in place within countries. In order to fully test all of the propositions, we formulate a hypothesis accounting for each of the institutional factors outlined by

Kshetri (

2015,

2018) in his framework. It is important to note that while formulating our hypotheses, we will use a different dependent variable, crowdfunding volume, instead of fundraising success proposed in

Kshetri (

2015). Following the logic of

Ahmad and Hoffmann (

2008), volumes can be considered a suitable measure of crowdfunding performance. When formulating the hypotheses, we expand

Kshetri’s (

2015,

2018) propositions to include a broader view of crowdfunding. We argue that the legitimacy of all types of crowdfunding (debt-based, equity-based, reward-based, donation-based) is affected by all institutions, albeit to a different extent depending on the type of crowdfunding in question. We also substitute some of the institutional variables proposed by

Kshetri (

2015,

2018) with variables that we expect to provide a more direct linkage to crowdfunding volumes. The following sections cover the hypotheses related to the three pillars, regulative, cultural-cognitive, and normative institutions, in turn.

2.1. Regulative Institutions and Crowdfunding

La Porta et al. (

1998) suggest that much of the differences in financial development between countries are a result of the prevailing legal system and how efficiently laws are enforced.

Kshetri (

2015) considers crowdfunding regulations to be especially important for equity-based crowdfunding. Still, having formal laws that define the rights and responsibilities of each party is likely to increase the legitimacy of all crowdfunding platforms. Rules and referees should be considered particularly important for situations based on competitive interests, such as markets (

Scott 2014). Thus, platforms offering pecuniary rewards should be affected most, as each party is expected to prioritize his/her (financial) interest. Platforms offering non-pecuniary rewards are less likely to be affected by regulations and more likely to be affected by the normative and cultural-cognitive factors. Yet, it is conceivable that the existence of crowdfunding regulations will improve the legitimacy of crowdfunding as a whole, regardless of the type of crowdfunding. Indeed,

Miglo and Miglo (

2019) note that firms may exhibit an overall preference towards crowdfunding as opposed to traditional bank financing if bankruptcy costs are high. As such, countries with very strict bankruptcy laws may exhibit relatively higher crowdfunding volumes for all types of crowdfunding.

While institutional theory states that regulations legitimize and thus empower social objects, it may still be possible that regulations are put in place as a result of higher crowdfunding volumes. When investigating the timing of crowdfunding regulations’ implementation and the development of crowdfunding volumes, we see that both scenarios have been realized in countries where formal rules have been set in place. For example, Belgium, France, Spain, Great Britain, Portugal, and Slovenia have experienced a significant increase in the growth rate of crowdfunding volumes per year following the introduction of regulations compared to the year prior to the introduction of regulations. However, in Austria and Germany, the growth rate of crowdfunding volumes has decreased (but remains positive) following the introduction of regulations.

3 This indicates that the presence of crowdfunding regulations may indeed increase the legitimacy of crowdfunding and may not be just a mere reflection of the increased popularity of this activity. Legitimacy is also increased if the rules are enforced (

North 2008). As greater enforcement of crowdfunding regulations is likely if rules are formally written down, we propose that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Crowdfunding volumes are greater in countries with regulatory framework supporting crowdfunding activities.

Due to the relative novelty of crowdfunding, most countries have not yet established crowdfunding-specific regulations. Moreover, the European Commission is of the opinion that member states should take only proportional action in regulating crowdfunding (

European Commission 2018). A review of crowdfunding regulation by the European Crowdfunding

Network (

2017) shows that only 11 out of 32 countries analyzed have regulations in place that specifically target crowdfunding. In light of this,

Kshetri (

2015) emphasizes the importance of a country’s overall regulatory framework in supporting entrepreneurship as a key factor determining the success of equity-based crowdfunding. We argue that crowdfunding is less likely to be influenced by regulations aimed at the general entrepreneurial climate and more likely to be affected by regulations targeted specifically at financial services. Both debt-based and equity-based crowdfunding are likely to be more directly affected by financial services regulations because of their similarities to financial markets. However, spillover effects on the legitimacy of reward- and donation-based crowdfunding could also occur. Therefore, we frame the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Crowdfunding volumes are greater in countries with more favorable regulatory climate for the provision of financial services.

Crowdfunding is (by nature) a highly democratic process, which may be incompatible with authoritarian regimes (

Kshetri 2015). In authoritarian regimes, regulatory systems take on extreme values (

Scott 2014) and the enforcement of rules is undertaken by non-neutral agents (

North 1990). As a result, strong regulations do not always support the legitimacy claims of social objects, because authoritarian regimes may use regulations to further their own interest. The latter may not necessarily combine well with advancements that are democratic by nature. Crowdfunding is highly reliant on the development of information technology which, according to

Pitroda (

1993), can be considered one of the greatest democratizing tools ever created. As we have seen, some authoritarian regimes (e.g., Russia) have used regulations to control the use of such technology.

Kshetri (

2015) points out that because crowdfunding calls for the democratic participation of a large group of investors, this is likely to conflict with the measures of top-down control imposed on information and communications technology by authoritarian regimes. We, therefore, propose that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Crowdfunding volumes are greater in more democratic countries.

2.2. Cultural-Cognitive Institutions and Crowdfunding

Cultural-cognitive institutions cover the potential effects of attitudes that societies “take for granted” (

Scott 2014). These should be viewed separately from regulative institutions because they tend to also incorporate perceptions that have been learned from past institutions (

Tabellini 2010). Cultural-cognitive institutions are not formed instantaneously and may, therefore, incorporate a rich history of the development of widely accepted perceptions.

Following this logic, we must also consider the implications of cultural beliefs on the use of e-services (services provided through the Internet). The use of e-services requires certain skills and an attitude favoring their use. Cultural factors determine what people deem sensible (

Ostrom 2008). Therefore, if the use of e-services is considered sensible because of trust in machines, speed, etc., then it is likely to also be reflected in their active use. As crowdfunding is based on transactions carried out using the Internet, the countries with more favorable e-services culture are also expected to exhibit greater crowdfunding volumes. Therefore, the hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Crowdfunding volumes are greater in countries with more favorable e-service culture.

Crowdfunding may also be influenced by the level of trust within a society because it empowers the claims of legitimacy of crowdfunding platforms (

Kshetri 2015). Contributing or investing on crowdfunding platforms usually involves supporting a cause initiated by a stranger, requiring a certain amount of trust in his/her good intentions. Furthermore, crowdfunding is typically characterized by high levels of information asymmetry (

Belleflamme et al. 2014;

Kleinert et al. 2020;

Miglo 2020).

Sriram (

2005) notes similar issues in his study of the emerging field of microfinance in India, and finds that social trust becomes a highly effective tool to overcome issues arising from imperfect information and enable microfinance to develop. Trust is particularly important in countries with a weak record of enforcing contracts (

Wu et al. 2014), effectively becoming a substitute for a strong regulatory environment (

Karlan 2005). Accordingly, the trust within a society should be considered especially important in countries without crowdfunding-specific regulations in place. In such countries, lending funds on a crowdfunding platform would leave the lender with little action to take if the borrower defaults (

Rau 2018). Therefore, a high degree of thin trust between strangers should support crowdfunding success. We phrase our hypothesis accordingly:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Crowdfunding volumes are greater in countries characterized by greater trust between strangers.

Social stigmatization has been associated with a number of economic consequences, such as low institutional ownership, weak analyst coverage, and discounted equity values for companies that are in conflict with social norms (

Novak and Bilinski 2018). Similarly,

Kshetri (

2018) argues that a high degree of stigmatization of entrepreneurial failure would lead to lower crowdfunding success. While

Landier (

2005) points out that all entrepreneurial activities are negatively affected by the stigma of failure,

Kshetri (

2018) argues that this is even more so for funding campaigns conducted on crowdfunding platforms. The reasoning behind this lies in the sheer number of contributors that crowdfunding campaigns normally mobilize. When an entrepreneur fails in a venture financed by more traditional methods, only a small group of experienced investors will know about it and the feeling of shame will be less pronounced. However, as crowdfunding campaigns are open to the wider public, failure will also become public knowledge and the humiliation will, therefore, be greater. It should also be considered that failure is perceived differently in different cultures. For example, the EY Global Entrepreneurship Barometer 2013 points out that attitudes towards business failure are particularly positive in the U.S. where 43% of respondents viewed failure as an opportunity to learn, while the G20 average was 23%. Moreover, risk-taking by individuals tends to vary, depending on whether the country is more collectivistic or individualistic (for a review, see

Illiashenko and Laidroo 2020).

Kshetri’s (

2018) proposition regarding this matter is framed through the normative indicator of stigmatization in society, while we believe it is more realistic to measure the cultural-cognitive trait of fear of entrepreneurial failure, which is why we have phrased our hypothesis accordingly:

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Crowdfunding volumes are greater in countries characterized by lower fear of entrepreneurial failure.

2.3. Normative Institutions and Crowdfunding

Following

Scott (

2014), normative institutions must incorporate the norms and values of the society that are put in place by social obligation. This means that participants on a crowdfunding platform ask themselves whether participating in a campaign would be considered socially appropriate. A key ingredient in normative institutions affecting crowdfunding is the degree of philanthropic involvement present in society (

Kshetri 2015). As philanthropy describes involvement in projects that are brought into life in order to forward some mutual values (

Ostrander 2007), it is a straightforward example of what

Scott (

2014) describes as normative institutions.

Kshetri (

2015) argues that philanthropic involvement is especially important for donation-based crowdfunding but may also affect reward-based crowdfunding. However, because of the uncertainty of returns in crowdfunding in general, we do not cast aside the possibility that the degree of philanthropic involvement in society could also have some positive influence on the volumes of debt-based and equity-based platforms. We, therefore, propose:

Hypothesis 7 (H7). Crowdfunding volumes are greater in countries characterized by greater levels of philanthropic involvement.

Kshetri (

2015) also emphasizes the power of trade associations for providing legitimacy. Trade associations are normative institutions in that they are unable to sanction noncompliant non-members for actions deemed unacceptable, but rather enforce a social obligation to become a member and abide by the common set of rules. There are some signs of the emergence of country-based crowdfunding-specific associations. For example, in the UK, twelve leading crowdfunding platforms established a self-regulatory body that required all members to operate to a defined minimum standard (

Crowdcube 2013). However, the online presence of platforms seems to have led to the emergence of mainly continent-wide associations such as the European Crowdfunding Network and the African Crowdfunding Association. The existence of such associations makes it difficult to assess their impact on country-specific crowdfunding volumes. Instead, we focus on the financial services cluster as a whole. If the cluster is well-developed, there are likely to be specific and strong cluster organizations that also provide legitimacy to crowdfunding. We, therefore, phrase our final hypothesis as:

Hypothesis 8 (H8). Crowdfunding volumes are greater in countries with more developed financial services cluster.

3. Data and Methodology

We obtained data on crowdfunding volumes from CCAF. This data is gathered through surveys, wherein platforms self-report their annual volumes and answer numerous questions regarding their businesses. To date, it is the best data source for country-level crowdfunding volumes because alternative sources (e.g., Massolution, TAB Dashboard) have been shown to significantly underestimate crowdfunding volumes, especially outside of the U.S. It is important to note that CCAF may also somewhat underestimate the volumes, as some platforms fail to respond to the survey. CCAF does specify that the data covers nearly 90% of volumes in Europe and about two-thirds of volumes in the Asia-Pacific region.

Crowdfunding in CCAF’s survey is distributed into 19 different categories, which we reclassify into the following five types: debt-based, equity-based, reward-based, donation-based, and other crowdfunding. Debt-based crowdfunding covers all platforms that include the term “lending” or “debt” in CCAF’s classification, as well as invoice trading, which is also considered a type of debt financing. Equity-based crowdfunding encompasses all platforms, wherein the definition provided by CCAF refers to the use of equity or revenue/profit sharing models. We also consider mini-bonds as equity-based transactions, because of their short duration and unsecured nature. Reward-based crowdfunding includes only the platforms labeled reward-based by CCAF, while donation-based crowdfunding includes platforms labeled donation-based. Other crowdfunding covers the data from platforms that were not distributed into the previously mentioned types, such as community shares and pension-led funding.

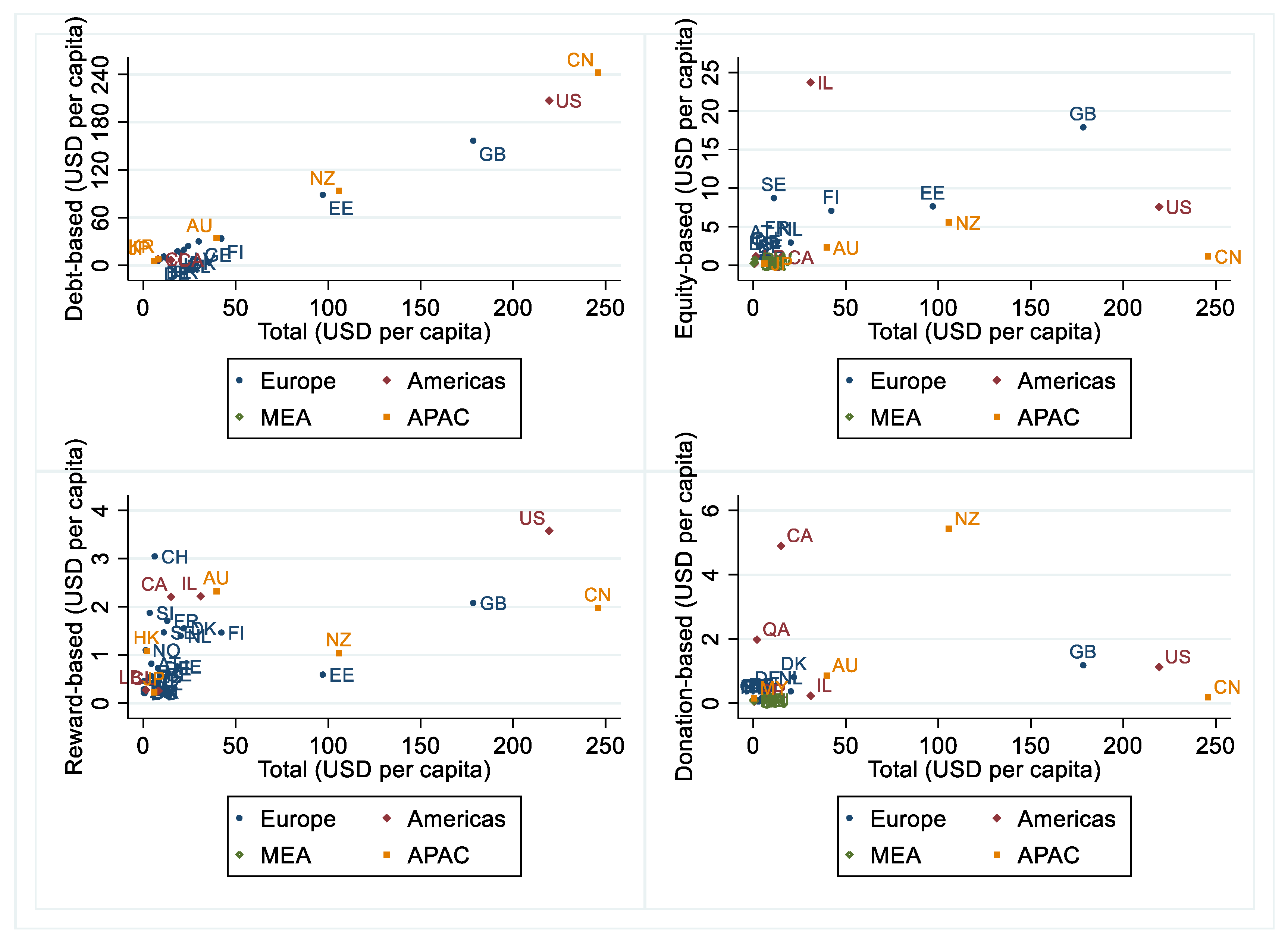

The dataset initially includes crowdfunding data for 160 countries across the world during 2015–2016. In estimations, the number of countries decreases to 122 and below due to missing data for some of the control variables. This means that compared to the original CCAF dataset we lose data for at least 38 countries accounting for 0.065% of total global crowdfunding volume, with Middle Eastern and African countries accounting for nearly half of the number of countries lost. In robustness tests, we also use the data for 2013 and 2014 which for most countries has been backfilled during the 2015 survey and covers only 121 countries.

There exists a significant variation in crowdfunding volumes across countries of different sizes. Therefore, the use of raw volumes can provide misleading indications. In order to control for the size of the country, we use a relative measure of crowdfunding volumes (

cf_total) calculated as country-specific total crowdfunding volume in USD over the entire estimation period divided by the average population of a country over the same period. The population is preferred as the scale variable due to its lower volatility compared to GDP. A similar approach has been used in several recent studies focusing on crowdfunding and FinTech credit e.g., (

Claessens et al. 2018;

Rau 2018). This ratio exhibits significantly greater values for five countries—China, the U.S., Great Britain, Estonia, and New Zealand. In

Table A5 in

Appendix A under robustness test 2, we provide some results for regression models excluding these extreme observations. As the results were not significantly affected, we decided to keep these somewhat extreme observations and there through also maintain the sample size. Instead, in regression models, we use a log transform of

cf_total to cope with its extreme values and the skewness of its distribution. In addition to the indicator for total crowdfunding volume, we employ similar country-specific volume measures for the specific types of crowdfunding defined above.

Institutional variables are selected based on the empirical proxies which could be obtained for the maximum number of countries. In case several alternatives were identified, preference was given to those variables which could be more directly linked to crowdfunding activity. We were also forced to make some compromises when determining the measurement unit of variables. For example, as the trust between strangers has been measured using different scoring systems in two different surveys covering somewhat different sets of countries, the number of observations could be maintained only through the use of a dummy variable.

Table 1 presents the variables used for each of the pillars with their description and descriptive statistics. The first letter of each institutional indicator refers to either regulative (

r), cultural-cognitive (

c), or normative (

n) pillar, as explained in

Section 2.

We also control for several non-institutional country-specific indicators covering economic development, the size of the non-traditional financial sector and characteristics of the traditional financial sector. Economic development is proxied with a log transform of GDP per capita (

mgdpp). The size of the non-traditional financial sector is proxied by the personal remittances received as a % of GDP (

mremit) because remittances have been shown to act as substitutes for the traditional financial sector in countries with less developed financial systems (

Giuliano and Ruiz-Arranz 2009). Characteristics of the traditional financial sector are proxied by the top 5 bank concentration ratio (

mtop5) and the financial development index (

mfdi).

All of the regression estimations in this paper will be based on a cross-sectional dataset due to the following reasons. First, reliable estimates for crowdfunding volumes are present only for two years (2015–2016). Therefore, a panel design would add little value in light of many of the explanatory variables having very low variation across such a short time period. Second, even if institutional variables change over time, their impact may be more clearly visible several years after the change. A potential caveat of the cross-sectional design is the omitted variable bias and the low number of observations. We try to address these concerns by considering different model specifications and reducing the number of control variables.

4 The estimations remain vulnerable to endogeneity concerns. In order to respond to the endogeneity concerns, we did estimate some equations with explanatory variables taken from 2014 (see

Table A4 and

Table A5 in

Appendix A); however, it did not significantly change the results reported hereafter. As the explanatory variables do not also vary significantly over time, we decided to use the average of 2015–2016 in baseline estimations. We also have to consider multicollinearity. This was done by checking variance inflating factors (VIFs) and pair-wise correlations. The mean of VIFs for all estimations are presented at the bottom, of each table containing the results. The pair-wise correlations of explanatory variables are presented in

Table A1 in

Appendix A. As country-based controls

mgdpp and

mfdi are strongly correlated, the baseline combination will include only the former indicator.

We estimate each cross-sectional regression model using simple ordinary least squares with robust standard errors. All explanatory variables in these models represent an average over 2015–2016. In those robustness tests where we use crowdfunding volume data covering the period of 2013–2016, the explanatory variables are calculated as averages over 2013–2016. In order to see the explanatory power of different types of institutional variables and to maintain the maximum number of observations per model, the first set of regression models is estimated so that each hypothesis is tested in a separate model:

The dependent variable (CFi) refers to the log transform of the crowdfunding volume per capita (cf_total) in country i. The institutional variable sets (Inst) include one institutional variable at a time with the exception of H1 which includes two regulatory variables at once. Country-specific non-institutional variables will be the same in every model.

In order to control for the simultaneous impact of several institutional variables, the following set of regression models will include all institutional variables with the exception of trust and entrepreneurial failure (H5 and H6). The latter variables are excluded due to their significantly lower number of observations. The models take the form:

Equations (2) and (3) differ in terms of the first two variables used to capture regulatory framework (H1) and variables cacc and cpay used to capture e-service culture (H4). In Equation (4), compared to Equation (2), the GDP per capita (mgdpp) indicator is replaced with the financial development index (mfdi). As the simultaneous consideration of hypotheses increases the number of control variables, the estimations are followed by a backward elimination procedure until the model includes only those explanatory variables which are statistically significant at p < 10% level. All three equations will be estimated with total crowdfunding volumes and Equation (2) for all types of crowdfunding excluding equity-based crowdfunding. Equation (3) will be employed to estimate the determinants of equity-based crowdfunding.

Several robustness tests will also be carried out. First, Equations (2)–(4) (together with backward eliminations) will be run including also variables for trust (ctrust) and fear of entrepreneurial failure (cfear). This reduces the number of observations, but enables to see the results of the simultaneous consideration of all institutional variables. Second, Equation (2) (together with backward eliminations) will be estimated for the time period 2013–2016 for total crowdfunding volumes and its types (with the exception of Equation (3) estimated for equity-based crowdfunding). This reduces the number of countries and increases the vulnerability of the estimations to the potential misstatements. However, it does enable to capture the robustness of reported associations over a longer time period. Third, in order to address the endogeneity concerns, we estimate the Equations (1) and (2) using explanatory variables from 2014. Fourth, to address the concerns over the potential impact of outliers, we estimate Equation (2) excluding the observations of the five countries with the greatest volume per capita.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the results of our paper show that many of the institutional aspects proposed in the theoretical literature as relevant crowdfunding determinants do indeed survive the empirical tests. Institutions seem to be important vehicles in the spreading acceptance of crowdfunding, as they provide legitimacy to this novel way of financing and mitigate woes such as imperfect information, moral hazard, and diverging incentives. Regulative and cultural cognitive institutions are especially important determinants of crowdfunding volumes, while normative institutions provide rather inconclusive results. The results of this paper should be considered especially important for policymakers, as governments have numerous levers to influence a country’s institutional structures. For instance, if policymakers are interested in promoting crowdfunding to improve access to financing, implementing, and enforcing clear crowdfunding-specific regulations could help legitimize crowdfunding in the eyes of both investors and those seeking funds. Shaping cultural beliefs with initiatives promoting the use of e-services as a reliable way of transacting could also contribute to the increase of crowdfunding volumes. In addition to policymakers, managers of crowdfunding platforms could campaign for stronger industry regulations and promote their platforms as a credible way of obtaining financing or investing money for the wider public, in an attempt to increase the legitimacy of their businesses and, with that, the volume of transactions mediated through their platforms.

It is noteworthy that institutional variables provide a more significant and robust association with crowdfunding volumes compared to country-specific non-institutional variables. This implies that even if crowdfunding could be an economically rational choice for projects looking for financing in some countries, we may still see only minuscule crowdfunding volumes in such countries if local institutions are unwelcoming towards crowdfunding. These results also provide significant insight for future research by indicating a need to incorporate institutional variables as controls in future models focusing on crowdfunding volumes. However, there are some important caveats to consider when interpreting these results. First and foremost, we were not able to explicitly test for causality due to data restrictions, which leaves a possibility that some variables (i.e., crowdfunding-specific regulations) may exhibit correlation with crowdfunding volumes because they themselves are responding to the change in crowdfunding volumes. Another factor to keep in mind is that the role of institutions may become less pronounced over time, as crowdfunding becomes more widely accepted as a widely approved method of raising funds.

In conclusion, this paper provides a much-needed understanding of at least one set of factors that help to explain the adoption rate of crowdfunding globally. It, therefore, breaks away from the academic literature on crowdfunding that has so far mostly focused on single platforms or regions and gives a more generalized view of this phenomenon. The paper also contributes to a growing area of empirical research that highlights how institutions interact with digital innovations and what role they have in determining whether these innovations are legitimate and, therefore, accepted for wider use. Keeping in mind the fast growth of crowdfunding and the more proactive stance some countries have taken in regulating this phenomenon in recent years, it would be interesting to repeat this study in the future to examine how the effects of institutions evolve over time.