Capital Structure as a Mediating Factor in the Relationship between Uncertainty, CSR, Stakeholder Interest and Financial Performance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

3. Research Methodology

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| SR # | Coding | Variables | Rating | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN | SUI | N | SI | I | |||

| I | Uncertainty | ||||||

| 1. | UN1 | Market uncertainties | |||||

| 2. | UN2 | Labor uncertainties | |||||

| 3. | UN3 | Liability uncertainties | |||||

| 4. | UN4 | Inflation uncertainties | |||||

| 5. | UN5 | Interest rate uncertainties | |||||

| 6. | UN6 | Exchange rate uncertainties | |||||

| 7. | UN7 | Society related uncertainties | |||||

| 8. | UN8 | Policy related uncertainties | |||||

| 9. | UN9 | Competitive uncertainties | |||||

| 10. | UN10 | Economic environment uncertainties | |||||

| 11. | UN11 | Technological environment uncertainties | |||||

| 12. | UN12 | Raw material uncertainties | |||||

| 13. | UN13 | Regulatory uncertainties | |||||

| II | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | ||||||

| (i). | CSR—Risk and Market Opportunities | SD | D | N | A | SA | |

| 1. | CSRR1 | The financial risk profile of a firm has no influence on CSR activities | |||||

| 2. | CSRR2 | It is rational to engage in CSR activities without any concerns about the availability of free cash flow to fund these activities | |||||

| 3. | CSRR3 | Entrance of new competitors or substitute products is most likely to occur in sectors where CSR firms operate | |||||

| 4. | CSRR4 | If there are two identical firms, where one is socially responsible and the other is not, the former would have less downside risk and encounters fewer events detrimental to its bottom line | |||||

| 5. | CSRR5 | Firms in a highly competitive environment engage in CSR projects to gain competitive advantages | |||||

| 6. | CSRR6 | Attracting new partners for refinancing capital requirement becomes easy for socially responsible firms. | |||||

| 7. | CSRR7 | Being socially responsible, it is easier to identify new business opportunities and manage all market risks. | |||||

| 8. | CSRR8 | Firms with good social performance have more opportunities for increased sales and new markets. | |||||

| (ii). | CSR—Financial Growth | SD | D | N | A | SA | |

| 9. | CSRFG1 | Introducing CSR in financial practices does not facilitate easy availability of trade credits or credit from other sources, like financial institutions, for short-term financing. | |||||

| 10. | CSRFG2 | CSR firms remain at par with conventional firms, while raising capital for financing growth opportunities. | |||||

| 11. | CSRFG3 | In CSR firms, financial leverage is higher due to lower cost of debt. | |||||

| 12. | CSRFG4 | CSR firms may lessen average cost of capital due to ease of availability of sources of funds | |||||

| 13. | CSRFG5 | Investing in CSR activities is a kind of re-investment where firm’s retained earnings can be utilized. | |||||

| 14. | CSRFG6 | Firms practice ethical values due to competitive pressures and their focus on short-term profits. | |||||

| 15. | CSRFG7 | Firms should not forgo short-run gains, even if it can expect better returns in the long-run | |||||

| 16. | CSRFG8 | The net result of CSR expenditure translates into profitability as this expenditure is an investment and not an expenditure. | |||||

| 17. | CSRFG9 | Ethical practices, even at a financial cost, will enhance financial performance and growth of businesses. | |||||

| 18. | CSRFG10 | CSR expenditure is a strategic decision of firms which entitles them to tax relief. | |||||

| 19. | CSRFG11 | Firms should not reserve any amount of profit for socially responsible activities | |||||

| 20. | CSRFG12 | Liberal participation in CSR activities could impact the financial performance and competitiveness of the business | |||||

| III | Stakeholder Interest | UN | SUI | N | SI | I | |

| 1. | SI1 | Financial decisions are influenced by the major shareholders (>5% of shares outstanding) of the firm | |||||

| 2. | SI2 | Financial decisions are influenced by the minority shareholders (<5% of shares outstanding) of the firm | |||||

| 3. | SI3 | Financial decisions are influenced by the long-term creditors of the firm | |||||

| 4. | SI4 | Financial decisions are influenced by relevant government agencies | |||||

| 5. | SI5 | Financial decisions are influenced by the employees of the firm. | |||||

| 6. | SI6 | Financial decisions are influenced by the customers of the firm | |||||

| 7. | SI7 | Financial decisions are influenced by the suppliers of the firm | |||||

| 8. | SI8 | Financial decisions are influenced by the media | |||||

| 9. | SI9 | Financial decisions are influenced by special interest groups, e.g., environmentalists | |||||

| 10. | SI10 | Financial decisions are influenced by the competitors of the firm | |||||

| IV | Financial Performance | UN | SUI | N | SI | I | |

| 1. | FP1 | Long-run firm profitability | |||||

| 2. | FP2 | Growth rate of sales and revenues | |||||

| 3. | FP3 | Return on assets (ROA) | |||||

| 4. | FP4 | Growth rate of return on assets (ROA) | |||||

| 5. | FP5 | Market share | |||||

| 6. | FP6 | Operational and cost efficiency | |||||

| 7. | FP7 | Productivity | |||||

| 8. | FP8 | Level of return on sales | |||||

| 9. | FP9 | Growth rate of return on sales | |||||

| V | Capital Structure Decision | SD | D | N | A | SA | |

| 1. | CS1 | The balance between long-term debt and equity has a significant impact on firm value | |||||

| 2. | CS2 | Firms should pursue a target debt to equity ratio | |||||

| 3. | CS3 | Firms should leave some of its debt financing capacity unused to provide financial slack | |||||

| 4. | CS4 | Firms that experience financial distress have a capital structure that has an over-reliance on the use of long-term debt capital | |||||

| Use of Alternative Sources of Financing | UN | SUI | N | SI | I | ||

| 5. | CSASF1 | Short-term bank loans | |||||

| 6. | CSASF2 | Long-term debt | |||||

| 7. | CSASF3 | Equity rights issue | |||||

| 8. | CSASF4 | New equity issues | |||||

| 9. | CSASF5 | Retained earnings | |||||

References

- Aguilera, Ruth V., Deborah E. Rupp, Cynthia A. Williams, and Jyoti Ganapathi. 2007. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review 32: 836–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, Zuraidah, Norhasniza Mohd Hasan Abdullah, and Shashazrina Roslan. 2012. Capital structure effect on firm performance: Focusing on consumers and industrials sectors on Malaysian firms. International Review of Business Research Papers 8: 137–55. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, Alka, and Pervaiz Alam. 2005. CEO compensation and stakeholder claims. Contemporary Accounting Research 22: 519–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Kee-Hong, Jun-Koo Kang, and Jin Wang. 2011. Employee treatment and firm leverage: A test of the stakeholder theory of capital structure. Journal of Financial Economics 100: 130–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Kee-Hong, Sadok El Ghoul, Omrane Guedhami, Chuck CY Kwok, and Ying Zheng. 2019. Does corporate social responsibility reduce the costs of high leverage? Evidence from capital structure and product market interactions. Journal of Banking & Finance 100: 135–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Shantanu, Sudipto Dasgupta, and Yungsan Kim. 2008. Buyer–supplier relationships and the stakeholder theory of capital structure. Journal of Finance 63: 2507–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, Chester Irving. 1938. The Functions of the Executive. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, p. 376. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, Sidney L., Ned C. Hill, and Srinivasan Sundaram. 1989. An empirical test of stakeholder theory predictions of capital structure. Financial Management 18: 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, Christopher F., Andreas Stephan, and Oleksandr Talavera. 2009. The effects of uncertainty on the leverage of nonfinancial firms. Economic Inquiry 47: 216–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boubaker, Sabri, and Duc Khuong Nguyen. 2014. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility: Emerging Markets Focus. Singapore: World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, Glenn W., and Graeme A. Guthrie. 2003. Investment, uncertainty, and liquidity. Journal of Finance 58: 2143–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradley, Michael, Gregg A. Jarrell, and E. Han Kim. 1984. On the existence of an optimal capital structure: Theory and evidence. Journal of Finance 39: 857–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglayan, Mustafa, and Abdul Rashid. 2014. The response of firms’ leverage to risk: Evidence from UK public versus nonpublic manufacturing firms. Economic Inquiry 52: 341–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capon, Noel, John U. Farley, and Scott Hoenig. 1990. Determinants of financial performance: A meta-analysis. Management Science 36: 1143–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatterjee, Sayan, Robert M. Wiseman, Avi Fiegenbaum, and Cynthia E. Devers. 2003. Integrating behavioural and economic concepts of risk into strategic management: The twain shall meet. Long Range Planning 36: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chay, Jong-Bom, and Jungwon Suh. 2009. Payout policy and cash-flow uncertainty. Journal of Financial Economics 93: 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, Yee Peng, Junaina Muhammad, A. N. Bany-Ariffin, and Fan Fah Cheng. 2018. Macroeconomic uncertainty, corporate governance and corporate capital structure. International Journal of Managerial Finance 14: 301–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cua, Kristy O., Kathleen E. McKone, and Roger G. Schroeder. 2001. Relationships between implementation of TQM, JIT, and TPM and manufacturing performance. Journal of Operations Management 19: 675–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Thomas, and Lee E. Preston. 1995. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review 20: 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du, Shuili, Chitra Bhanu Bhattacharya, and Sankar Sen. 2011. Corporate social responsibility and competitive advantage: Overcoming the trust barrier. Management Science 57: 1528–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eisdorfer, Assaf. 2008. Empirical evidence of risk shifting in financially distressed firms. Journal of Finance 63: 609–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, Sadok, Omrane Guedhami, Chuck CY Kwok, and Dev R. Mishra. 2011. Does corporate social responsibility affect the cost of capital? Journal of Banking & Finance 35: 2388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elijido-Ten, Evangeline. 2006. Extending the Application of Stakeholder Theory to Malaysian Corporate Environmental Disclosures. Kuching: Faculty of Business and Enterprise, Swinburne University of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Edward. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R. Edward. 1999. Divergent stakeholder theory. Academy of Management Review 24: 233–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Edward, Andrew C. Wicks, and Bidhan Parmar. 2004. Stakeholder theory and “the corporate objective revisited”. Organization Science 15: 364–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedman, Milton. 1970. A Friedman doctrine: The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine 13: 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Galai, Dan, and Ronald W. Masulis. 1976. The option pricing model and the risk factor of stock. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girerd-Potin, Isabelle, Sonia Jimenez-Garces, and Pascal Louvet. 2011. The link between social rating and financial capital structure. Finance 32: 9–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givoly, Dan, Carla Hayn, Aharon R. Ofer, and Oded Sarig. 1992. Taxes and capital structure: Evidence from firms’ response to the Tax Reform Act of 1986. Review of Financial Studies 5: 331–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, Samuel B., and Sandra A. Waddock. 2000. Beyond Built to Last. Stakeholder Relations in “Built-to-Last” Companies. Business and Society Review 105: 393–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackbarth, Dirk, Christopher A. Hennessy, and Hayne E. Leland. 2007. Can the trade-off theory explain debt structure? Review of Financial Studies 20: 1389–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, Rolph E. Anderson, and Ronald L. Tatham. 1998. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice hall. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Milton, and Artur Raviv. 1991. The theory of capital structure. Journal of Finance 46: 297–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, Rick H., and Gregory T. Smith. 1994. Formulating clinical research hypotheses as structural equation models: A conceptual overview. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62: 429–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ittner, Christopher D., and David F. Larcker. 2001. Assessing empirical research in managerial accounting: A value-based management perspective. Journal of Accounting and Economics 32: 349–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jamali, Dima, and Charlotte Karam. 2018. Corporate social responsibility in developing countries as an emerging field of study. The International Journal of Management Reviews 20: 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, Jayant R., and Husayn Shahrur. 2007. Corporate capital structure and the characteristics of suppliers and customers. Journal of Financial Economics 83: 321–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramati, Abbas, Hamed Mehrabi, and Navid Mojir. 2010. A process-oriented perspective on customer relationship management and organizational performance: An empirical investigation. Industrial Marketing Management 39: 1170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandwalla, Pradip N. 1976. The techno-economic ecology of corporate strategy. Journal of Management Studies 13: 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, Naresh, and Brian D’Netto. 1997. Perceived uncertainty and performance: The causal direction. Journal of Applied Management Studies 6: 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, Rex B. 2005. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, Paul R., and Jay W. Lorsch. 1967. Organization and Environment. Boston: Harvard Business School, Division of Research. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Amnon, and Christopher Hennessy. 2007. Why does capital structure choice vary with macroeconomic conditions? Journal of Monetary Economics 54: 1545–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorca, Pedro, and Julita García-Diez. 2004. The relation between firm survival and the achievement of balance among its stakeholders: An analysis. International Journal of Management 21: 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- MacKie-Mason, Jeffrey K. 1990. Do taxes affect corporate financing decisions? Journal of Finance 45: 1471–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaritis, Dimitris, and Maria Psillaki. 2010. Capital structure, equity ownership and firm performance. Journal of Banking & Finance 34: 621–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffery, Kate, Robert Hutchinson, and Robert Jackson. 1997. Aspects of the finance function: A review and survey into the UK retailing sector. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 7: 125–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Ronald K., Bradley R. Agle, and Donna J. Wood. 1997. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review 22: 853–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, Franco, and Merton H. Miller. 1958. The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. The American Economic Review 48: 261–97. [Google Scholar]

- Modigliani, Franco, and Merton H. Miller. 1963. Corporate income taxes and the cost of capital: A correction. The American Economic Review 53: 433–43. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, Stewart C. 1984. The capital structure puzzle. The Journal of Finance 39: 574–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntim, Collins G., and Teerooven Soobaroyen. 2013. Corporate governance and performance in socially responsible corporations: New empirical insights from a Neo-Institutional framework. Corporate Governance: An International Review 21: 468–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, James E., Lee E. Preston, and Sybille Sauter-Sachs. 2002. Redefining the Corporation: Stakeholder Management and Organizational Wealth. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Lee E., and Douglas P. O’Bannon. 1997. The corporate social-financial performance relationship: A typology and analysis. Business and Society 36: 419–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, Kartik, and Husayn Shahrur. 2008. Relationship-specific investments and earnings management: Evidence on corporate suppliers and customers. Accounting Review 83: 1041–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, Abdul. 2013. Risks and financing decisions in the energy sector: An empirical investigation using firm-level data. Energy Policy 59: 792–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, Axel K. D., Anne Wu, and Chee W. Chow. 2010. Environmental uncertainty, comprehensive performance measurement systems, performance-based compensation, and organizational performance. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics 17: 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, Sankar, Chitra Bhanu Bhattacharya, and Daniel Korschun. 2006. The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34: 158–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfman, Mark P., and Chitru S. Fernando. 2008. Environmental risk management and the cost of capital. Strategic Management Journal 29: 569–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, Jan-Benedict E. M., and Hans Baumgartner. 2000. On the use of structural equation models for marketing modeling. International Journal of Research in Marketing 17: 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, Mark C. 1995. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review 20: 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swamidass, Paul M., and William T. Newell. 1987. Manufacturing strategy, environmental uncertainty and performance: A path analytic model. Management Science 33: 509–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titman, Sheridan. 1984. The effect of capital structure on a firm’s liquidation decision. Journal of Financial Economics 13: 137–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titman, Sheridan, and Roberto Wessels. 1988. The determinants of capital structure choice. Journal of Finance 43: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, Rupal. 2012. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Financial Performance and Competitiveness of Business: A Study of Indian Firms. Ph.D. dissertation, Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee, India. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeeten, Frank H. M. 2006. Do organizations adopt sophisticated capital budgeting practices to deal with uncertainty in the investment decision? A research note. Management Accounting Research 17: 106–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwijmeren, Patrick, and Jeroen Derwall. 2010. Employee well-being, firm leverage, and bankruptcy risk. Journal of Banking & Finance 34: 956–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, Ivo. 2004. Capital structure and stock returns. Journal of Political Economy 112: 106–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| (SR.) Variables | Factors | Values | Factors | Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (I.) Uncertainty | Chi-square/df | 3.278 | RMSEA | 0.054 |

| AGFI | 0.838 | GFI | 0.918 | |

| TLI | 0.896 | CFI | 0.932 | |

| (II.) CSR | Chi-square/df | 3.911 | RMSEA | 0.052 |

| AGFI | 0.817 | GFI | 0.911 | |

| TLI | 0.891 | CFI | 0.813 | |

| (III.) Stakeholder Interest | Chi-square/df | 3.060 | RMSEA | 0.043 |

| AGFI | 0.853 | GFI | 0.939 | |

| TLI | 0.904 | CFI | 0.916 | |

| (IV.) Financial Performance | Chi-square/df | 4.199 | RMSEA | 0.059 |

| AGFI | 0.744 | GFI | 0.907 | |

| TLI | 0.887 | CFI | 0.897 | |

| (V.) Capital Structure | Chi-square/df | 3.062 | RMSEA | 0.057 |

| AGFI | 0.851 | GFI | 0.945 | |

| TLI | 0.910 | CFI | 0.916 |

| Variables | Mean | St. Dev. | UNC | CSR | STI | FP | CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNC | 3.849 | 0.712 | 1.00 | ||||

| CSR | 4.179 | 0.516 | −0.241 * | 1.00 | |||

| STI | 3.901 | 0.491 | −0.224 * | 0.221 | 1.00 | ||

| FP | 3.956 | 0.805 | −0.536 ** | 0.336 ** | 0.253 * | 1.00 | |

| CS | 3.608 | 0.782 | −0.453 ** | 0.314 ** | 0.225 * | 0.542 ** | 1.00 |

| Variables | Firm Age | N | Mean | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty | <10 | 7 | 3.3429 | 4.688 | 0.008 |

| 10–20 | 24 | 3.6472 | |||

| 21–30 | 21 | 3.6222 | |||

| >30 | 9 | 3.7741 | |||

| Total | 61 | 3.9486 | |||

| CSR | <10 | 7 | 2.8776 | 2.736 | 0.052 |

| 10–20 | 24 | 2.8861 | |||

| 21–30 | 21 | 3.4388 | |||

| >30 | 9 | 3.6429 | |||

| Total | 61 | 3.8792 | |||

| Stakeholder Interest | <10 | 7 | 4.3129 | 4.201 | 0.009 |

| 10–20 | 24 | 3.9121 | |||

| 21–30 | 21 | 3.6705 | |||

| >30 | 9 | 3.0878 | |||

| Total | 61 | 3.9008 | |||

| Financial Performance | <10 | 7 | 3.4762 | 3.906 | 0.013 |

| 10–20 | 24 | 2.7569 | |||

| 21–30 | 21 | 2.7143 | |||

| >30 | 9 | 3.6481 | |||

| Total | 61 | 3.9563 | |||

| Capital Structure | <10 | 7 | 3.3016 | 4.863 | 0.004 |

| 10–20 | 24 | 2.3683 | |||

| 21–30 | 21 | 2.3976 | |||

| >30 | 9 | 3.4938 | |||

| Total | 61 | 3.6515 |

| Indexes of Fit of the Direct Model | Indexes of Fit of Indirect Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Values | Factors | Values |

| Chi-square/df | 3.751 | Chi-square/df | 3.982 |

| NFI | 0.908 | NFI | 0.901 |

| GFI | 0.929 | GFI | 0.911 |

| AGFI | 0.873 | AGFI | 0.841 |

| TLI | 0.858 | TLI | 0.873 |

| CFI | 0.904 | CFI | 0.907 |

| RMSEA | 0.052 | RMSEA | 0.059 |

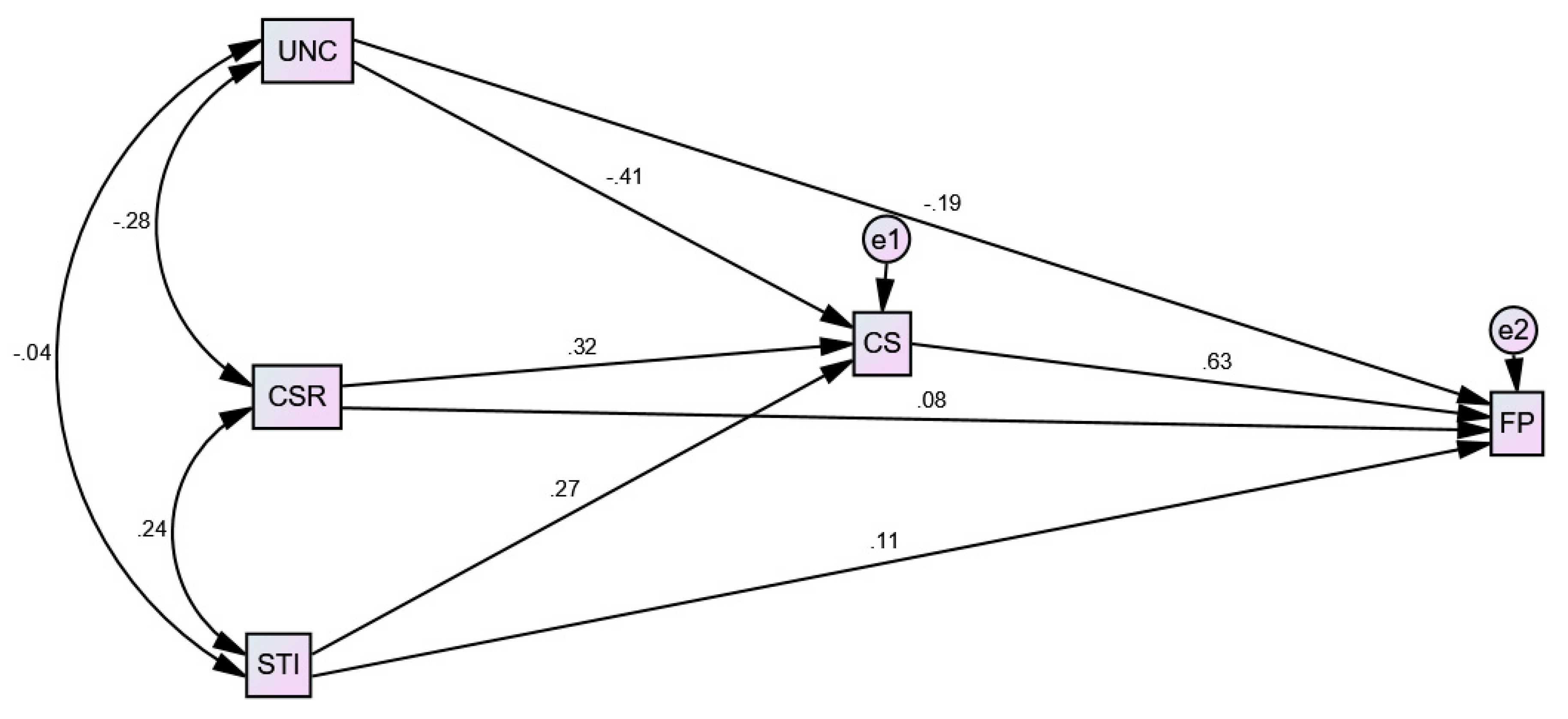

| Variables | Estimate | p-Value | Hypotheses Support | VIF | Tol. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Performance | <--- | Uncertainty | −0.454 | 0.000 | H1-supported | 1.137 | 0.880 |

| Financial Performance | <--- | CSR | 0.322 | 0.008 | H2-supported | 1.252 | 0.799 |

| Financial Performance | <--- | Stakeholder Interest | 0.293 | 0.014 | H3-supported | 1.114 | 0.898 |

| Variables | Estimate | p-Value | Hypotheses Support | VIF | Tol. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Performance | <--- | Capital Structure | 0.632 | (0.000) | H4-supported | 1.513 | 0.661 |

| Capital Structure | <--- | Uncertainty | −0.413 | (0.000) | H5-supported | 1.336 | 0.749 |

| Capital Structure | <--- | CSR | 0.320 | (0.014) | H7-supported | 1.252 | 0.799 |

| Capital Structure | <--- | Stakeholder Interest | 0.274 | (0.030) | H9-supported | 1.144 | 0.874 |

| Variables | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Hypotheses Support | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | p-Value | Estimate | p-Value | ||||

| Financial Performance | <--- | Uncertainty | −0.454 | 0.000 | −0.193 | (0.020) | H6-supported |

| Financial Performance | <--- | CSR | 0.322 | 0.008 | 0.081 | (0.353) | H8-supported |

| Financial Performance | <--- | Stakeholder Interest | 0.293 | 0.014 | 0.108 | (0.317) | H10-supported |

| (SR.) Variables | Standard Estimate (≥ 0.50) | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|

| (I.) Uncertainty | I.1-11: 0.73, 0.67, 0.71, 0.66, 0.78, 0.88, 0.83, 0.79, 0.16, 0.75, 0.84, 0.37, 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.94 |

| (II.) CSR—Risk and Market Opportunities | II.1-3: 0.31, 0.23, 0.38, 0.42, 0.25, 0.69, 0.83, 0.87 | 0.64 | 0.84 |

| CSR—Financial Growth | II.4-12: 0.26, 0.56, 0.74, 0.76, 0.79, 0.83, 0.28, 0.86, 0.81, 0.72, 0.68, 0.19 | 0.57 | 0.92 |

| (III.) Stakeholder Interests | III.1-9: 0.65, 0.95, 0.36, 0.74, 0.77, 0.71, 0.89, 0.87, 0.85, 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.94 |

| (IV.) Financial Performance | IV.1-4: 0.71, 0.89, 0.81, 0.62, 0.32, 0.15, 0.29, 0.46, 0.41 | 0.58 | 0.85 |

| (V.) Capital Structure Decision | V.1-3: 0.93, 0.82, 0.88 | 0.58 | 0.91 |

| Use of Alternative Sources of Financing | V.4-6: 0.90, 0.76, 0.65, 0.61, 0.82 | 0.57 | 0.87 |

| Discriminant Validity | Nomological Validity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | AVE | Correlated Variables | IC | SIC | p-Value | Decision | ||

| CSR Uncertainty | 0.64, 0.57 0.58 | CSR | <--> | UNC | −0.131 | 0.017 | 0.008 | Supported |

| Uncertainty Stakeholder Interest | 0.58 0.62 | UNC | <--> | STI | −0.302 | 0.091 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Uncertainty Financial Performance | 0.58 0.58 | UNC | <--> | FP | −0.270 | 0.073 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Uncertainty Capital Structure | 0.58 0.58, 0.57 | UNC | <--> | CS | −0.264 | 0.070 | 0.000 | Supported |

| CSR Stakeholder Interest | 0.64, 0.57 0.62 | CSR | <--> | STI | 0.080 | 0.006 | 0.013 | Supported |

| CSR Financial Performance | 0.64, 0.57 0.58 | CSR | <--> | FP | 0.322 | 0.104 | 0.000 | Supported |

| CSR Capital Structure | 0.64, 0.57 0.58, 0.57 | CSR | <--> | CS | 0.360 | 0.130 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Stakeholder Interest Financial Performance | 0.62 0.58 | STI | <--> | FP | 0.081 | 0.007 | 0.013 | Supported |

| Stakeholder Interest Capital Structure | 0.62 0.58, 0.57 | STI | <--> | CS | 0.074 | 0.005 | 0.016 | Supported |

| Financial Performance Capital Structure | 0.58 0.58, 0.57 | FP | <--> | CS | 0.782 | 0.612 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Sr. No. | Variables | Source | Items | Valid Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Uncertainty | Verbeeten (2006) | 13 | 11 | 0.864 |

| 2. | CSR | Tyagi (2012) | 20 | 12 | 0.792 |

| 3. | Stakeholder Interest | Elijido-Ten (2006) | 10 | 09 | 0.837 |

| 4 | Financial Performance | Schulz et al. (2010) | 09 | 04 | 0.851 |

| 5. | Capital Structure | McCaffery et al. (1997) | 09 | 08 | 0.916 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hunjra, A.I.; Verhoeven, P.; Zureigat, Q. Capital Structure as a Mediating Factor in the Relationship between Uncertainty, CSR, Stakeholder Interest and Financial Performance. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2020, 13, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13060117

Hunjra AI, Verhoeven P, Zureigat Q. Capital Structure as a Mediating Factor in the Relationship between Uncertainty, CSR, Stakeholder Interest and Financial Performance. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2020; 13(6):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13060117

Chicago/Turabian StyleHunjra, Ahmed Imran, Peter Verhoeven, and Qasim Zureigat. 2020. "Capital Structure as a Mediating Factor in the Relationship between Uncertainty, CSR, Stakeholder Interest and Financial Performance" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13, no. 6: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13060117

APA StyleHunjra, A. I., Verhoeven, P., & Zureigat, Q. (2020). Capital Structure as a Mediating Factor in the Relationship between Uncertainty, CSR, Stakeholder Interest and Financial Performance. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(6), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13060117