Crisis and the Role of Money in the Real and Financial Economies—An Innovative Approach to Monetary Stimulus

Abstract

1. Introduction

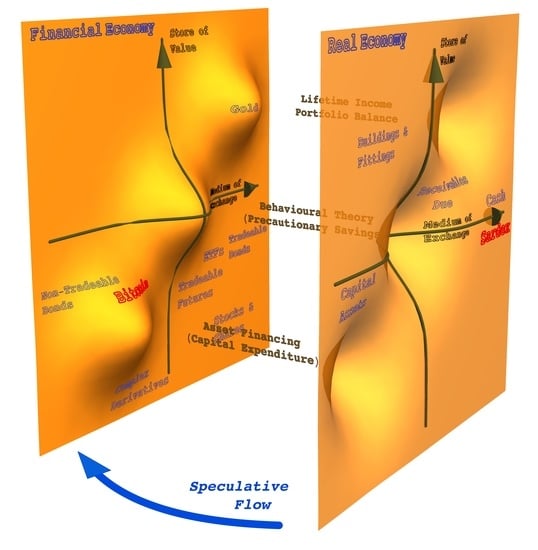

2. Results

2.1. The Roots of Divergence

2.2. The Liquidity Continuum

2.3. The Role of Expectations

3. Discussion

3.1. The Overall Economy

3.1.1. Money, Transactions and GDP

- If x is total transaction volume (e.g., expressed in US$ transacted per year) we are dealing with the original Equation (4) and the variables are defined as above, but including also all asset purchases and sales in the financial economy. Specifically, Broad Money.

- If x is GDP, then the relevant monetary mass is defined as a subset of M, namely , that corresponds to the product and service transactions that actually made use of it; V and P are unchanged in concept although clearly they can change in value; and T refers only to those product and service transactions recorded within GDP. In this case we set . We note also that in this case V is dubbed the ‘income velocity of circulation’.

- If x is set as traded GVA, or J, then our output measure no longer equates to GDP, the difference being due to non-traded GVA such as . For traded GVA we should be using in place of P, i.e., the average difference in price between two steps in the same supply chain, which measures the value added. Adopting this input/output approach allows our value-added measure to be evaluated independently of a specific stage of production, obtainingwhere the subscript R makes the emphasis on the real economy explicit and is a factor that expresses the fraction of the monetary mass that participates in the traded gross value-adding.

- Finally, x could also be , non-traded GVA, whose monetary mass we call .

3.1.2. The Role of Value Added

3.2. The Two Economies

3.2.1. Different Kinds of Circulations in the Two Economies

3.2.2. Linkages Between the Real and Financial Economies

3.3. Monetary Mass

3.3.1. Real Economy Endogenous Money Demand

3.3.2. Financial Economy Endogenous Money Demand

- (i)

- Traded derivatives, options and futures

- (ii)

- Equity

- (iii)

- Government bonds (T-Bills/Gilts etc)

- (iv)

- Commercial investment-grade bonds

- (v)

- Non-investment-grade bonds

- (vi)

- Residential real estate

- (vii)

- Commercial real estate

- (viii)

- Cash

3.3.3. Exogenous Money

3.4. The Velocity of Circulation in the Financial Economy

3.5. Crisis Onset and the Minsky Moment

3.6. Healing the Real Economy

- a shortage of liquidity (working capital) on the supply side; here targeted intervention during the same circulation should lead to a rapid upward adjustment of J, since freeing the working capital constraint should lead to a significantly larger number of supply-chain transactions;

- a shortage of demand due to a lack of purchasing capability: this is an area that traditional helicopter money has targeted;

- a shortage of capacity or lack of productivity on the supply side due to financing constraints on new capital investment. Investment is needed to raise both productivity and capacity of the supply side. There will be some increase in J during the same circulation due to expansion activities (building, new machinery, etc), but the increase in J will keep going in subsequent years due to the greater output that the larger capacity affords. This third intervention increases the value of our coefficient .

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Economic Analysis

- Circulation. The term circulation is used by both Keynes (1930) and Schumpeter (1934). In Keynes’s case he uses it to split the real from the speculative economy and as a tool to understand monetary flows and income distribution. Schumpeter uses it to express a trading flow through a series of Walrasian-type self-clearing markets.

- Quantity Equation. We make extensive use of the Fisher (1911) Quantity Equation. This identity offers many insights when it is combined with understanding the definitional challenges relating to which transactions are implicated in a monetary circulation. Specifically, we believe that transactions associated with GDP only tell part of the story, which is why there is a need to incorporate the financial economy explicitly in the analysis.

- Money Creation. We embrace concepts of both endogenous (Hahn 1924) and central bank exogenous (QE) (Joyce et al. 2011) money creation as being appropriate in specific settings. We do not seek or attempt to add to the very extensive literature on money demand equations.

4.2. Data Sources

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Definitions of Key Terms

- Collateral is pledged assets available to be sold to repay a debt.

- Financial Economy is the set of markets where buyers and sellers trade assets for both yield and capital gain.

- Leverage is the financial multiplier that is applied to a ‘margin’ deposit in a trading account and is underpinned by collateral security held against the permitted leverage.

- Lifetime Income, sometimes referred to as the Permanent Income Hypothesis, refers to the process economic actors use to plan savings, withdrawals and returns on assets held to allow them to optimize their income over their whole expected life.

- Liquidity describes the free cash available to meet liabilities.

- Liquidity Preference refers to economic actors’ preference to hold cash even if it means they miss out on financial returns that could be available from holding other assets.

- M1 is cash and money held in ‘on-demand’ bank accounts.

- M2 is M1 plus savings deposits, small (under US$100k) time deposits, and retail money market funds.

- Margin is the deposit that is made into a trading account that allows the trader to trade a nominal value of specified assets that is up to some preset multiple of the deposited margin. The margin is held as immediately liquidatable security by the market maker (operator of the trading platform) against potential trading losses. Should losses exceed the required ‘margin’ amount the trader is subject to ‘margin calls’.

- Margin Call is a demand for an additional deposit into the trading account to cover existing or anticipated trading losses.

- Minsky Moment is when asset markets reset themselves to bring Ponzi asset financial economy valuations into line with real economy cashflows (Minsky 1989).

- MZM is M2 less small-denomination time deposits plus institutional money funds US Federal Reserve System (2020a).

- Natural Rate of Interest is the risk-adjusted interest rate that matches the Marginal Efficiency of Capital (Keynes 1936) meaning that the cost of finance equals the marginal return on capital (Wicksell 1898).

- Neutral Rate of Interest is the rate of interest needed to keep financial markets in balance with inflation as per the central bank target inflation rate (Lavoie 2003).

- Non-Traded Gross Value Added is the value added in the non-traded goods sector (principally government-provided services) and is represented by the symbol for ‘non-traded services’.

- Portfolio Balance refers to the process economic actors use to mix their asset holdings so as to optimize their yield, risk and access to cash.

- Real Economy is the set of markets in which consumers, firms, and government economic actors buy and sell products and services from each other.

- ‘Repo’ is a short-term (often under 24 hours) agreement to sell to and (via a reverse repo) repurchase the previous repo’d security at a pre-agreed price.

- ‘Reverse Repo’ is the original repo seller’s commitment to repurchase the security after the specified time-period.

- Saving means national income Y minus consumption C, where consumption includes consumption by individuals, firms and households. In formal models the definition requires adjustment for capital flows.

- Securities Settlement is the period of time specified by a trading platform between when a transaction is made and when it is netted against any others to establish an amount to be paid to or received from the agent trading.

- Shadow Banking denotes a group of financial institutions that mediate credit to borrowers but who are not subject to banking regulations.

- Solvency refers to the assets of an economic actor being sufficient to cover their liabilities.

- Traded Gross Value Added represents the value added between inputs and outputs in traded goods and services and corresponds to J.

- Velocity of Circulation is how many times the monetary mass circulates in a given period (or, more precisely, how many times each unit of account circulates, on average, in a given period). Normally ‘Income velocity of circulation’ and is calculated as GDP/Monetary mass, whereas in other situations V could be defined as Transaction volume/Monetary mass.

- Wealth Effect is the indirect impact on the real economy of changes in the asset wealth of an economic actor in the financial economy.

References

- Adrian, Tobias, and Hyun Shin Shin. 2010. Liquidity and leverage. Journal of Financial Intermediation 19: 418–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Richard G., Michael Bordo, and John V. Duca. 2015. Money and Velocity during Financial Crises: From the Great Depression to the Great Recession. Available online: https://www.dallasfed.org/~/media/documents/research/papers/2015/wp1503.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Arrow, Kenneth J., and Gérard Debreu. 1954. Existence of an Equilibrium for a Competitive Economy. Econometrica 22: 265–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarudin, Z. E., Mohamed Ariff, and A. M. Khalid. 2013. Post-Keynesian money endogeneity evidence in G-7 economies. Journal of International Money and Finance 33: 146–62. [Google Scholar]

- BEA. 2020a. NIPA Handbook: Concepts and Methods of the U.S. National Income and Product Accounts. Available online: https://www.bea.gov/resources/methodologies/nipa-handbook (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- BEA. 2020b. Technical Note—Gross Domestic Product, Third Quarter of 2020 (Advance Estimate). Available online: https://www.bea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/gdp2q20_adv.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Bech, Morten L., Jenny Hancock, Rice Tara, and Amber Wadsworth. 2020. On the Future of Securities Settlement. Technical Report, Bank of International Settlements. BIS Quarterly Review. March. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3561195 (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Bernanke, Ben S. 2006. Monetary aggregates and monetary policy at the Federal Reserve: A historical perspective. Paper presented at Fourth ECB Central Banking Conference, Frankfurt, Germany, November 9–10, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- BOE. 1982. Supplementary Special Deposits Scheme. Available online: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/1982/the-supplementary-special-deposits-scheme.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- BOE. 2014. Money Creation in the Modern Economy. Available online: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/quarterly-bulletin/2014/q1/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy (accessed on 4 July 2020).

- Bordo, Michael D., Lars Jonung, and Pierre L Siklos. 1997. Institutional Change and the Velocity of Money: A Century of Evidence. Economic Inquiry 35: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borio, Claudio, and Piti Disyatat. 2010. TGlobal imbalances and the financial crisis: Reassessing the role of international finance. Asian Economic Policy Review 5: 198–216. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, Stephen. 2011. Measuring financial sector output and its contribution to UK GDP. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2011: 234–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cagan, Phillip. 1956. The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation. In Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money. Edited by Milton Friedman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cartas, Jose, and Artak Harutyunyan. 2017. Compilation, Source Data, and Dissemination of Monetary Statistics. In Monetary and Financial Statistics Manual and Compilation Guide. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Kaiji, Jue Ren, and Tao Zha. 2018. The nexus of monetary policy and shadow banking in China. American Economic Review 108: 3891–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophers, Brett. 2012. Anaemic geographies of financialisation. New Political Economy 17: 271–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, Corrine. 2011. The repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act and the current financial crisis. Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER) 9: 127–34. [Google Scholar]

- Culkin, Nigel, and Richard Simmons. 2018. Mastering Brexits Through the Ages: Entrepreneurial Innovators and Small Firms—The Catalysts for Success. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Culkin, Nigel, and Richard Simmons. 2019. Shock Therapy and Entrepreneurial Flare #Brexit. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 25: 338–52. [Google Scholar]

- Day, Richard H. 1994. Complex Economic Dynamics. Cambridge: MIT Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Debreu, Gérard. 1970. Economies with a Finite Set of Equilibria. Econometrica 38: 387–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleidi, Matteo, and Enrico S. Levrero. 2019. The Money Creation Process: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis for the United States. Metroeconomica 70: 552–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, Paolo, and Alexandros Kioupkiolis. 2019. The alter-politics of complementary currencies: The case of Sardex. Cogent Social Sciences 5. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23311886.2019.1646625 (accessed on 18 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Duca, John V. 2016. How capital regulation and other factors drive the role of shadow banking in funding short-term business credit. Journal of Banking & Finance 69: S10–S24. [Google Scholar]

- Economist. 2021a. China Leads in Precision-Guided Central Banking. Does It work? Free Exchange, February 13. [Google Scholar]

- Economist. 2021b. Transfer of power. Finance and Economics, February 6. [Google Scholar]

- FED. 2020. Money Stock Measures. H.6 Release Table 1 Footnotes. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h6/current/default.htm (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Feldstein, Martin. 1991. Reducing the Risk of Economic Crisis. Technical Report. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein, Martin S., and Charles Y. Horioka. 1980. Domestic saving and international capital flows. Economic Journal 90: 314–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FinancialStabilityBoard. 2020. Holistic Review of the March Market Turmoil. Available online: https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P171120-2.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Fisher, Irving. 1911. The Purchasing Power of Money: Its Determination and Relation to Credit, Interest and Crises. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- French, Kenneth R. 1988. Crash-testing the efficient market hypothesis. NBER Macroeconomics Annual 3: 277–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Milton. 1960. A Program for Monetary Stability. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Milton. 1962. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Milton. 1969. The Optimum Quantity of Money. In The Optimum Quantity of Money and Other Essays. Chicago: Adline Publishing Company, pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Milton, and Anna J. Schwartz. 1982. Monetary Trends in the United States and the United Kingdom: Their Relation to Income, Prices, and Interest Rates, 1867–1975. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (for Nat. Bur. Econ. Res.). [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, John Kenneth. 1961. The Great Crash, 1929: With a New Introduction by the Author. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Itay, Jonathan Witmer, and Jing Yang. 2018. Following the Money: Evidence for the Portfolio Balance Channel of Quantitative Easing. Technical Report, Paper No. 2018-33. Montreal: Bank of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, Frank. 1978. Exercises in Conjectural Equilibria. In Topics in Disequilibrium Economics. Edited by Steinar Strom and Lars Werin. Hoboken: Blackwell, pp. 64–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, L. Albert. 1924. Geld und Kredit: Gesammelte Aufsätze. Tübingen: J C B Mohr. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, James D. 1989. The long-run behavior of the velocity of circulation: A review essay. Journal of Monetary Economics 23: 335–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, Friedrich A. 1960. The Constitution of Liberty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Available online: https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.553409/page/n3 (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Heimer, Rawley, and Alp Simsek. 2019. Should retail investors’ leverage be limited? Journal of Financial Economics 132: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, John R. 1937. Mr Keynes and the Classics: A suggested interpretation. Econometrica 5: 147–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICMA. 2020. What Is Special in the Repo Market. Available online: https://www.icmagroup.org/Regulatory-Policy-and-Market-Practice/repo-and-collateral-markets/icma-ercc-publications/frequently-asked-questions-on-repo/9-what-is-a-special-in-the-repo-market/ (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- IMF. 2016. Monetary and Financial Statistics Manual and Compliation Guide. Available online: https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Data/Guides/mfsmcg_merged-web-pdf.ashx (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- IMF. 2017. Quarterly National Accounts Manual. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/qna/pdf/2017/QNAManual2017text.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- IMF. 2021. Gross Domestic Product: An Economy’s All. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/gdp.htm (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Joyce, Michael, Ana Lasaosa, Ibrahim Stevens, and Matthew Tong. 2011. The Financial Market Impact of Quantitative Easing in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Central Banking 7: 113–61. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, Michael, Matthew Tong, and Robert Woods. 2011. The United Kingdom’s Quantitative Easing Policy: Design, Operation and Impact. Technical Report, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin. London: Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- Juniper, James, Timothy P. Sharpe, and Martin J. Watts. 2014. Modern monetary theory: Contributions and critics. Journal of Post-Keynesian Economics 37: 281–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kahraman, Bige, and Heather Tookes. 2020. Margin trading and comovement during crises. Review of Finance 24: 813–46. [Google Scholar]

- Karpoff, Jonathan M. 1987. The Relation between Price Changes and Trading Volume: A Survey. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 22: 109–26. [Google Scholar]

- Keynes, John M. 1930. A Treatise On Money Vols I and II. New York: Harcourt Brace. [Google Scholar]

- Keynes, John M. 1936. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Saleheen. 2017. The savings and investment relationship: The Feldstein–Horioka puzzle revisited. Journal of Policy Modeling 39: 324–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Frank Hyneman. 1921. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, vol. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Krippner, Greta R. 2005. The financialization of the American economy. Socio-Economic Review 3: 173–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidler, David. 2006. Woodford and Wicksell on Interest and Prices: The place of the pure credit economy in the theory of monetary policy. Journal of the History of Economic Thought 28: 151–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidler, David, and George W. Stadler. 1998. Monetary Explanations of the Weimar Republic’s Hyperinflation: Some Neglected Contributions in Contemporary German Literature. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 30: 816–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, Marc. 2003. Measuring the natural rate of interest. Review of Economics and Statistics 85: 1063–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, Abba P. 1938. Saving equals investment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 52: 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littera, Giuseppe, Laura Sartori, Paolo Dini, and Panayotis Antoniadis. 2017. From an Idea to a Scalable Working Model: Merging Economic Benefits with Social Value in Sardex. International Journal of Community Currency Research 21: 6–21. Available online: https://ijccr.files.wordpress.com/2017/02/littera-et-al.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Lucas, Robert E., Jr. 1976. Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique. In The Phillips Curve and Labor Markets. Edited by Karl Brunner and Alan Meltzer. Carnegie Rochester Conference Series; New York: North Holland, pp. 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz, Harry M. 1952. Portfolio selection. Journal of Finance 7: 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Colell, Andreu. 1985. The Theory of General Economic Equilibrium: A Differentiable Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Minsky, Hyman P. 1982. Can “It” Happen Again?: Essays on Instability and Finance. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe. [Google Scholar]

- Minsky, Hyman P. 1989. The Financial Instability Hypothesis: A Clarification. Ph.D. Thesis, Bard College, Annandale-On-Hudson, NY, USA. Available online: http://digitalcommons.bard.edu/hm_archive/145 (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Muth, John F. 1961. Rational Expectations and the Theory of Price Movements. Econometrica 29: 315–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASDQ. 2020. SPX Historical Data. Available online: https://www.nasdaq.com/market-activity/index/spx/historical (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Obstfeld, Maurice, and Alan M. Taylor. 2005. Global Capital Markets: Integration, Crisis, and Growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson, Paul A. 1948. Economics, an Introductory Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, Joseph. 1934. The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Dhruv, Jean-Phillipe Bouchaud, Stanislao Gualdi, Marco Tarzia, and Francesco Zamponi. 2020. “V-, U-, L-or W-shaped recovery after COVID?” Insights from an Agent-Based Model June 2020 SSRN 3627505. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2006.08469.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2020).

- Sifma. 2020. US Repo Market Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.sifma.org/resources/research/us-repo-market-fact-sheet/ (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Simmons, Richard, Giuseppe Littera, Nigel Culkin, Paolo Dini, Luca Fantacci, and Massimo Amato. 2020. Helicopter, Bazooka or Drone? Economic Policy for the Coronavirus Crisis. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/helicopter-bazooka-drone-economic-policy-coronavirus-crisis-money// (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Stamp, Josiah C. 1931. The report of the Macmillan Committee. The Economic Journal 41: 424–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodder, James, and Bernard Lietaer. 2016. The Macro-Stability of Swiss WIR-Bank Credits: Balance, Velocity, and Leverage. Comparative Economic Studies 58: 570–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, Tobias. 1998. IWIR and the Swiss National Economy. Basel: WIR Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Summers, Lawrence H. 2015. Demand side secular stagnation. American Economic Review 105: 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarassow, Artur. 2019. Forecasting US money growth using economic uncertainty measures and regularisation techniques. International Journal of Forecasting 35: 443–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, John B. 1993. Discretion versus policy rules in practice. In Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy. North-Holland: Elsevier, vol. 39, pp. 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Tesar, Linda L. 1991. Savings, investment and international capital flows. Journal of International Economics 31: 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, Daniel L. 2014. QE: Is There a Portfolio Balance Effect? Technical Report, Review 96, No. 1. St. Louis: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- US Federal Reserve System. 2020a. Institutional Money Funds [WIMFNS], M2 Money Stock [WM2NS], Total Cash Balance [GDTCBW], General Account Balance at Federal Reserve [GDBFRW], Time and Savings Deposits at Commercial Banks [GDTSDCBM] & Demand Deposits at Commercial Banks [GDDDCBW] Money Zero Maturity [MZM]. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NBCB (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- US Federal Reserve System. 2020b. Quarter 2, 2020, Z.1 Financial Accounts of the United States (Sept 21, 2020). Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/apps/fof/FOFTables.aspx (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Werner, Richard. 1997. Towards a New Monetary Paradigm: A Quantity Theorem of Disaggregated Credit, with Evidence from Japan. Kredit und Kapital 2: 276–309. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, Richard. 2012. Towards a New Research Programme on ‘Banking and the Economy’—Implications of the Quantity Theory of Credit for the Prevention and Resolution of Banking and Debt Crises. International Review of Financial Analysis 25: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, Richard. 2014. How do banks create money, and why can other firms not do the same?An explanation for the coexistence of lending and deposit-taking. International Review of Financial Analysis 36: 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicksell, Knut. 1898. Interest and Prices. Translated by Richard Kahn. London: Macmillan for the Royal Economic Society. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Liu, Sweder van Wijnbergen, Xiaotong Qi, and Yuhuan Yi. 2019. Chinese shadow banking, financial regulation and effectiveness of monetary policy. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 57: 101169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | They argue that this unlimited capability is due to the supremacy of state-issued money, meaning that government debt should be seen as a financial asset for the private sector, not as a liability. |

| 2. | This article draws on many of the same concepts and is complementary but not intended as a specific follow-on to Werner’s work. |

| 3. | Please see Appendix A for definitions of technical terms. |

| 4. | For conceptual clarity, we assume that M is constant during the time-period used to calculate these variables. |

| 5. | Although we do not treat it in this article, as already mentioned the duration of a circulation can differ between the real and financial economies. |

| 6. | This savings/investment divergence is not associated with trade balance changes (Obstfeld and Taylor 2005). |

| 7. | As already stated, the implication is that the time duration of different circulations may be different, but this does not present a problem in the present analysis. |

| 8. | This is a major modelling step as it represents a strict additional constraint whose validity will need to be verified ex post by future empirical and mathematical research. This paper presents only the first tentative steps towards a possible model, modulated by the interactions shown in Figure 12 and Table 4, which could be expressed as additional equations. |

| 9. | In mathematics or physics this is called the ‘coupling’. |

| 10. | We note that changes in post-Pandemic saving behaviour are not yet clear. |

| 11. | In the macroeconomic identity for saving this diversion of funds to investment is seen as saving deployed as investment. |

| 12. | In a dynamic setting, to these must be added the import propensity to consume (how much of each $ of national income is spent on imports vs. home production) and the propensity to save (how much of each additional $ of income is saved). |

| 13. | Capital flows have special importance with respect to exchange rate constraints on central bank policy. |

| 14. | Open loan balances mean the amount of credit still available to be drawn down by the economic actor. |

| 15. | Since the 1970s, money has been created endogenously in both the real and financial economies unless there are ‘emergency’ administrative constraints (Badarudin et al. 2013), such as the UK 1973 Supplementary Special Deposits Scheme (BOE 1982) where credit creation levels were specified by the central bank. |

| 16. | L Albert Hahn had considerable influence on Josef Schumpeter. |

| 17. | Banks and central banks are the only institutions able to create official national currency. |

| 18. | The exception to this is when trading platforms (which may or may not be part of banks) create trading liquidity through margin trading prior to platform netting and settlement of any outstanding liabilities. |

| 19. | Professional traders in the USA are limited to a 1:50 leverage by the Dodd Frank Act of 2010, whilst commodity traders have a leverage limit of 1:20. |

| 20. | Surpluses can be reinvested into financial assets in anticipation of further price rises. |

| 21. | Short-term changes can be later reflected into M2 changes (Tarassow 2019). |

| 22. | Onset of the Euro-Dollar market in the 1960s, the dollar standard from 1971, the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980, and the 1999 repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act. |

| 23. | Each asset carries a future price change expectation, either “inheriting” this from the asset class or having its own expectation. For example, in late January 2021 GameStop had a different and more extreme price expectation than that of its asset class. |

| 24. | Say 50 or 100 basis points over the costs of the funds. |

| US$b | |

|---|---|

| M1 | 1446 |

| M2 | 2399 |

| MZM | 3130 |

| Broad Money | 8068 |

| Broad Money leveraged to: | |

| Futures | 22,709 |

| Options | 45,417 |

| CDS | 3000 |

| Commodities | 1000 |

| Equities | 1771 |

| Total | 73,897 |

| Leverage Factor | 916% |

| Contribution to ... | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Productive Value Added | Non-Traded Services | GDP Calculation | Wealth Calculation | |

| Sector | J | G | GDP () | H |

| Agriculture and Forestry | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Fishing | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Mining and Quarrying | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Manufacturing | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Electricity, Gas, Steam & Air Conditioning | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Water Supply | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Construction | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Wholesale and Retail | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Transportation and Storage | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Accommodation | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Food Services | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Information and Communication | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Financial and Auxiliary Services | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Insurance and Pensions | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Real Estate Services | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Professional, Scientific and Technical Serv. | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Administration and Support Services | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Public Admin., Defence, Social Security | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Education | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Human Health and Social Work (Gov.) | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Human Health and Social Work (Private) | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Arts, Entertainment and Recreation | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Asset Value Changes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Account | Account Variable | Mass Variable | Relation to Other Mass Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole economy | Tot. Transac. Vol. | M | = Broad Money |

| GDP | Y | ||

| Traded GVA | J | ||

| Non-traded Govt. GVA | |||

| Change in gross wealth | H |

| Real Economy | Financial Economy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact | Impact | |||||

| Flow | GDP | Asset Valuation | Impact Type | Assumptions | ||

| Savings | - | – | + | + | Direct | All new savings deployed into financial assets |

| Savings withdrawal | - | + | – | – | Direct | All savings withdrawals taken from assets |

| Equity investment | + (indirect) | + | + | – | Direct | Funded by existing, not new money |

| Bond issue | - | + | + | – | Direct | Funded by existing, not new money |

| Profit and loan interest | - | – | + | + | Direct | Assumes reinvestment of proceeds received |

| Management charges | + | + | – | – | Direct | Assumes funded by reduced reinvestment of profits |

| Savings returns | + | + | – | – | Direct | Assumes funded by reduced reinvestment of profits |

| Inbound capital flow | - | - | + | + | Direct | All deployed into financial assets |

| Outbound capital flow | - | - | – | – | Direct | All withdrawn from assets |

| Wealth effect | If it can increase consumption and vice versa | Indirect | ||||

| Name | Description | Real Economy | Financial Economy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | Physical notes and coins, and money in current accounts at banks | Yes | Yes | FED (2020) |

| M2 | M1 + savings, small time deposits, and retail money market funds | Yes | Yes | FED (2020) |

| Broad Money | M2 + eligible debt securities (paper that can be repo’d). In the USA this includes MZM. | Partial | Yes | Table 61, p. 182 in IMF (2016) |

| Net Broad Money | Broad Money − M2 | No | Yes | |

| MZM | (M2 − small term-deposits) + institutional money market funds | No | Yes | US Federal Reserve System (2020a) |

| Trading Leverage | Creation of trading credits against margin deposits | No | Yes |

| Impact on: | Real Economy | Monetary Mass | Leakages | Other | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Method | C | Traded GVA | non- TGVA | M | Real Econ. | Fin. Econ. | Saving | (Prod- uctivity) | Capital Gain | |

| Additional working capital | Mutual credit | + | |||||||||

| VC Conv. Debt | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Friedman helicopter drop | Cash to consumers | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | ||

| Smart helicopter working capital | Convertible tokens | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | |||

| Smart helicopter tokens | Tokens for domestic spend | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | |||

| Smart helicopter investment cash | VC equity & debt | + | + | + | ? | + | ? | ||||

| Conventional QE | Asset purchases | + | + | + | |||||||

| Rise in G | MMT | ? | + | + | ? | ||||||

| Structural monetary policy | Asian development model | + | + | + | + | ? | ? | ? | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simmons, R.; Dini, P.; Culkin, N.; Littera, G. Crisis and the Role of Money in the Real and Financial Economies—An Innovative Approach to Monetary Stimulus. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14030129

Simmons R, Dini P, Culkin N, Littera G. Crisis and the Role of Money in the Real and Financial Economies—An Innovative Approach to Monetary Stimulus. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2021; 14(3):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14030129

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimmons, Richard, Paolo Dini, Nigel Culkin, and Giuseppe Littera. 2021. "Crisis and the Role of Money in the Real and Financial Economies—An Innovative Approach to Monetary Stimulus" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 3: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14030129

APA StyleSimmons, R., Dini, P., Culkin, N., & Littera, G. (2021). Crisis and the Role of Money in the Real and Financial Economies—An Innovative Approach to Monetary Stimulus. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(3), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14030129