Below we report the results of the main statistical tests along with part of the robustness tests. We break down this section by first reporting the results of an OLS difference-in-difference test, then describing the results for each of the main dependent variables. Additional tests that test the robustness of the main results but are limited to being auxiliary have been moved to the internet appendix.

6.1. Summary Statistics

Panel A of

Table 1 shows a summary of the final sample. The application of the data filters yields a sample of 66,905 deals, of which 53,153 are domestic and 13,752 are cross-border, across 50 countries. As expected, a large proportion of deals in the sample (approximately 38%) occur in the U.S. Moreover, deals in the developed countries appear to make up the majority of the remaining observations.

Panel B of

Table 1 shows that developed markets appear to be net cross-border acquirers, illustrating their appetite to engage in deals with less-developed economies. The majority of deals involve private targets and acquirers, for which there is little to no firm-level information. However, including these deals increases the size of the dataset considerably and allows for more powerful testing. Therefore, the variables in the full sample tests are kept at the deal and country level.

Panel C of

Table 1 shows the top five industries, by volume, in which M&A deals took place throughout the full sample period. The figures shown are the mean number of deals per year for each industry before and after the mean year that social media becomes popular. There is a marked increase in deal volumes for all of the top five industries except for Depository Institutions. Although there was consolidation in this industry following the 2007–2008 global financial crisis, deal activity seems to have cooled as managers became reluctant to deploy capital for business combinations due to a tight regulatory environment. We expect social media to have a pervasive effect across the M&A market. However, industries with a greater public presence could be more prone to the information effects of social media (see

Table A1 in

Appendix A). In the same vein as the emerging markets hypothesis, lesser-known industries may benefit more from social media popularity in terms of M&A deal activity.

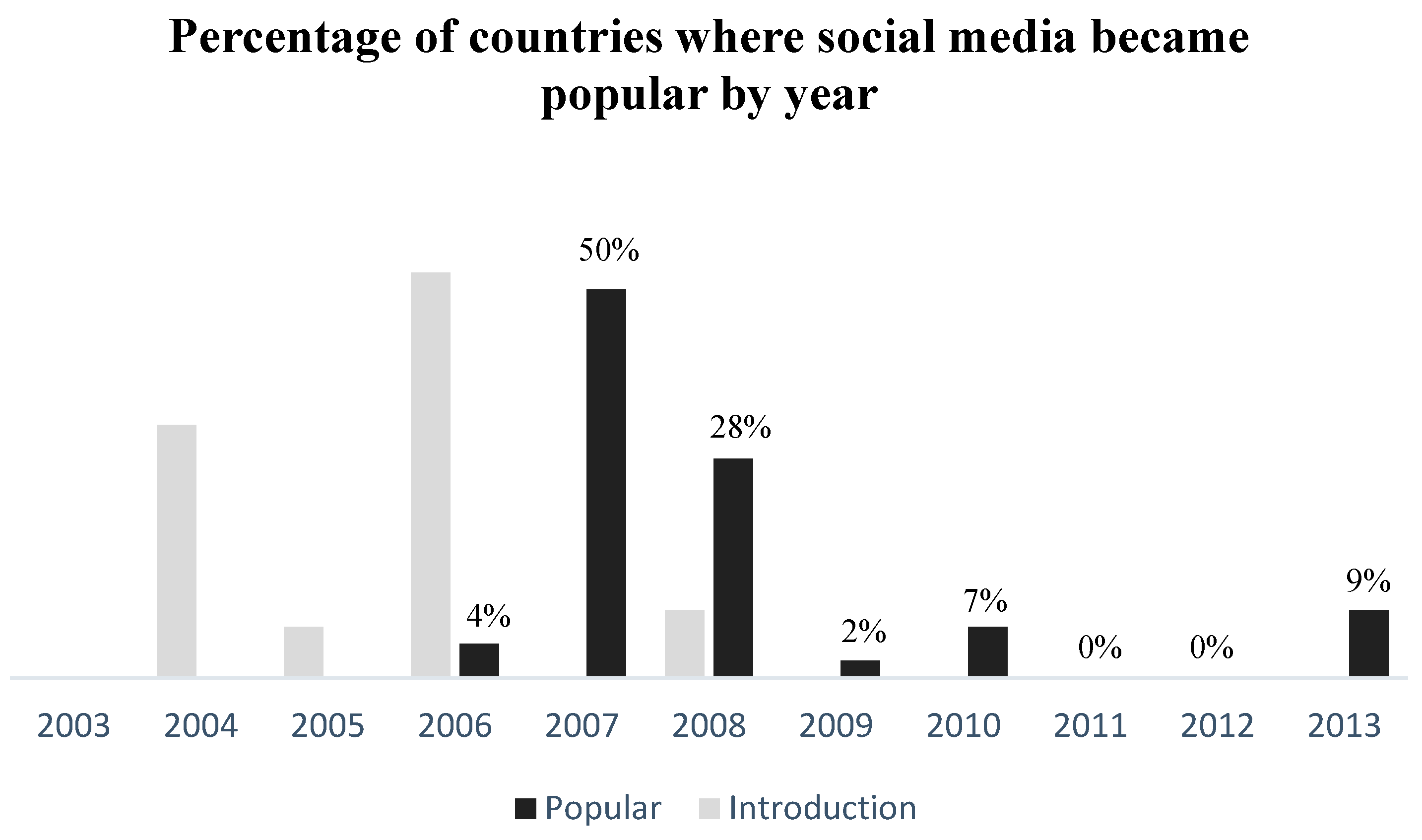

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of when social media was introduced and subsequently became popular across countries in the sample. A social media platform is deemed to be popular in a country when it reaches more than 50% users as a percentage of internet users in the country for that particular year. Therefore, in this setting, social media becomes popular in the year that the first platform reaches this particular threshold. Within the sample, it appears that the introduction of social media began in 2004 with the onset of popularity ranging from 2006 to 2013. The leading platforms such as Facebook and Twitter came into existence between 2004 and 2006, reaching widespread adoption by 2008 for over 80% of the countries. On average, it took 2.6 years since introduction to reach popularity within that country.

This study focuses on “social networking” applications that are used for connecting people, communities, and companies to enable interaction over the internet through messaging apps, news feeds and mass information dissemination. We distinguish this type of application from other types of social media such as photography (e.g., Instagram or Flickr) or communication platforms (e.g., Skype or Viber). By narrowing the criteria in this way, Facebook and Twitter becomes the two dominant platforms that determine social media popularity across countries. Therefore, in order to establish when social media became popular in a country, it is simply a matter of determining which one of those platforms became popular in that country first, regardless of which platform was introduced before the other.

Table 2 shows the split between Facebook and Twitter popularity in the sample. Columns 1 and 2 show the number and percentage of countries where that social media platform was the first to become popular, respectively. Column 3 shows the mean year in which that platform became popular across countries. This data was hand-collected from Google search trends, Statista, World Bank and various news articles in Factiva.

The above descriptive statistics warrant further discussion, as the experimental setup relies heavily on the given social media data. The data clearly exhibit a cluster around the years 2007 and 2008. This limits the cross-sectional variation of when social media became popular across countries and the explanatory power of the tests are expected to suffer due to this.

By including year and country fixed effects, double-clustered standard errors, and difference-in-difference methodologies, we attempt to control for the social media year-clustering issues. Further robustness tests are done with ‘internet introduction’ as the main independent variable. This measure is used as an alternative to social media popularity and takes out any scaling issues that are present in the latter measure, i.e., introduction of the internet does not rely on a user quantity criterion in each country.

The full list of platforms examined to determine social media introduction and popularity are provided in

Table A3 in the

Appendix A.

Figure 2 shows the well-documented phenomenon of ‘merger waves’ with peaks occurring just before the bursting of the dot-com bubble and onset of the 2007–2008 global financial crisis. Time fixed effects in all subsequent tests are included to control for variations due to these specific periods. Mean deal values closely track deal volumes, as expected, but are skewed due to a number of large deals as can be seen by the disparity between the mean and median values in

Figure 2.

The vertical line indicating the mean year in which social media became popular across countries is also shown in

Figure 2. There does not appear to be an obvious trend in volume or mean value following this date.

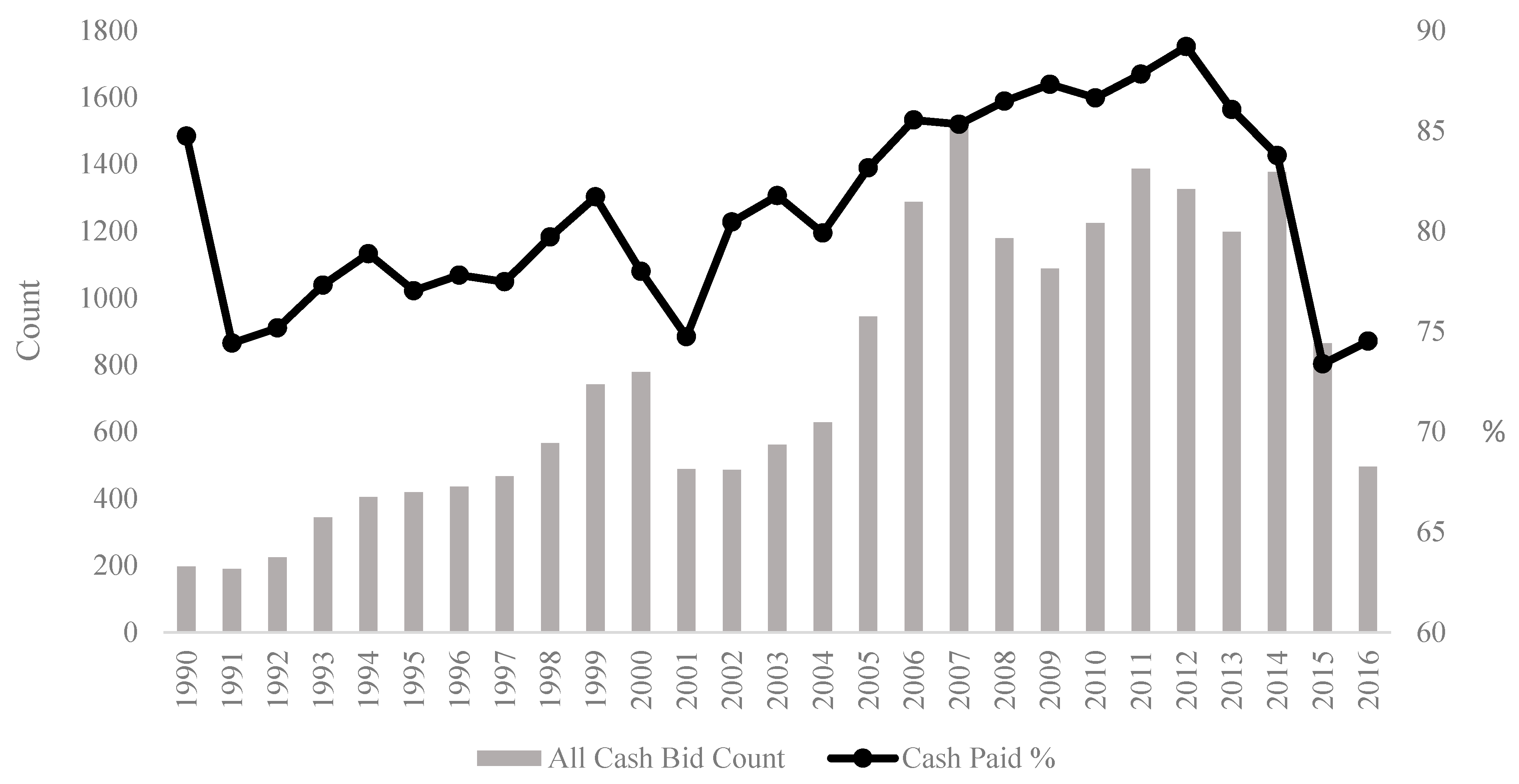

Figure 3 shows the trend in cash as a medium of exchange in M&A deals globally. All-cash bids decrease substantially at the onset of the 2007–2008 global financial crisis and level out before dipping again to an eighteen-year low in 2016. The percentage of cash consideration stays high even during the financial crisis but follows the downward trend of all-cash bids after 2012.

It is evident from both

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 that M&A transactions were influenced by the 2007–2008 global financial crisis, which occurred contemporaneously with the rise of social media popularity. Caution must be taken to consider not only the short-term but also long-term or permanent shifts in deal-making strategies due to the crisis.

The effects of the financial crisis on the M&A variables examined are expected to have the opposite effects to that which social media is hypothesised. Specifically, due to a squeeze in financing throughout most economies during and following the crisis, the ability to pay for M&A transactions was limited. Borrowing for the purposes of LBOs, M&A’s and share repurchases decreased significantly in 2008 due to illiquidity in the banking sector (

Ivashina and Scharfstein 2010). This decrease in takeover appetite (seen in

Figure 2) should also have a negative influence on the incidence of competitive bids. It may be argued that depressed asset prices may encourage bargain purchases in the corporate takeover market. However, the downturn in the real global economy, in addition to tight credit conditions should in fact be a catalyst for managers to focus on strategically defensive measures, such as deleveraging the balance sheet and implementing disciplinary measures to increase operational efficiencies (

Campello et al. 2010). Instead of pursuing an acquisition strategy to survive the crisis, which would be costly in terms of both time and money, firms would be engaging in internal operational restructurings, thus putting downward pressure on the participation and competitiveness of the M&A market.

Even in the case when deals were being struck during the crisis, the tight credit markets would also point to larger proportions of cash to finance the deals. With depressed equity valuations, cash will be a more attractive way to pay for acquisitions. Cheap credit following the crisis—as global interest rates were cut to new lows—would also have been utilised to finance those acquisitions that did occur.

These effects are ones that we expect purely due to the dynamics caused by the financial crisis, ceteris paribus. In isolation, these effects seem to support an opposite relationship with the M&A variables we examine. Therefore, it is important to take note of the significant events that occurred when social media was becoming popular.

Table 3 reports the summary statistics of the main variables used in this study as well as the control variables. These variables are described in more detail in the following section. We split the summary statistics into two separate periods: the full period from 1990 to 2016, and a shortened period with observations 3 years before and after social media becomes popular for each country. The latter period shows the more granular changes in mean values of each of the variables.

Panel A shows that competing bids actually decreased following SocialMedia, contrary to H2. It also appears that cash payments, both CashPaid and AllCash increased following SocialMedia popularity; again, a counterfactual to our hypothesis. Other notable changes in deal characteristics are the increase in deals backed by financial sponsors (15.5% of all deals announced involve a financial sponsor following SocialMedia, compared to only 8.9% before), an increase in cross-border deal volume, and an increase in overall deal values. There is a large decrease in private deals following SocialMedia which may be a result of the financial crisis hampering private company deal appetite. This is also contrary to expectations as social media should improve the visibility of private firms, resulting in more deal activity involving them.

Panel B tells a different story with respect to the incidence of competing bids; a 30% increase in the proportion of competing bids following social media popularity in a country, which is consistent with our hypothesis. The amount of cash paid—using both measures—remains contrary to the initial prediction. However, the increase is less than what is observed in Panel A.

Panel C shows further descriptive statistics where deals in countries of early adopters of social media are compared to deals in countries of late adopters. The ‘Difference’ column shows the percentage difference before and after social media popularity.

Early adopters are defined as countries where social media became popular in 2006 or 2007, and late adopters are defined as countries where social media became popular in any year after 2007 (i.e., from 2008 to 2013). The split between early and late adopters is 25 and 21 countries, respectively. The incidence of competing bids has increased by approximately 40% for early adopters compared to late adopters after social media becomes popular in a country. However, the p-value in the final column suggests this is not statistically different from 0. Cash paid had a muted and statistically significant increase for early adopters. This is in contrast to the 0.6% decrease in all cash bids. Another notable statistic here is the 3.5% decrease in the incidence of deals involving a private company. This is an unexpected result given that social media is expected to improve the presence of private companies in the M&A market.

Due to the clustering of social media popularity around the years 2007 and 2008 it is possible that the dichotomy between late and early adopters may not be clean enough to identify an effect. We provide descriptive statistics where late adopters are classified as those countries where social media became popular in either 2010 or 2013 (i.e., excluding 2008 and 2009). This provides an adequate time lapse between early and late adopters to further isolate the effect of social media. Panel D of

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics of this alternative sample. There is a statistically significant difference of positive 47% in the mean incidence of competing bids following social media popularity.

CashPaid also decreases slightly but the difference is not statistically significant. In addition to this difference-in-means analysis, we conduct a difference-in-difference test on each of the main dependent variables in the following section.

6.3. Probit Regression Results

A competing bid can be submitted after a deal has been publicly announced and will usually result in higher bid premiums or more optimal suitors to the target. A decrease in information asymmetries is expected to allow potential competing bidders to respond with better due diligence and abilities to assess sentiment around the deal.

Table 7 reports the results from the probit regressions. All marginal effects described in this section can be found in

Table A2 in the

Appendix A. We find that

SocialMedia is positive and statistically significant at 10% for all model specifications. For model 2, where both fixed effects and double-clustered standard errors are included, the marginal effect when

SocialMedia equals 1 is a 7.7% increase in the probability of a competing bid at 10% significance. The coefficients on

PSM and

DVS are statistically significant, suggesting competition for deals involving private firms and smaller deals have been affected more by social media.

The coefficients on most control variables appear to be consistent with findings in past literature. Coefficients on

Hostile, DealValue, Tender, Termination, Litigation and LBO are all positive and statistically significant in regression 2. Inconsistent with

Chemmanur et al. (

2009),

Cash is also positive—implying that competing bids are more likely with cash offers.

Chemmanur et al. (

2009) test only publicly traded firms in the U.S., which could present a bias in their tests, resulting in the inconsistency with figures in this study. Furthermore, statistical significance of their result is weak (barely at the 10% level) and they also find a positive (but statistically insignificant) coefficient when a slightly altered regression model is used. The positive and significant coefficient on

Termination is also surprising, when compared to prior literature.

Bates and Lemmon (

2003) find that termination fee clauses deter competing bids

prior to deal announcement. There appears to be lesser competing bids when the deal involves a cross-border transaction. As expected, better governance standards within the target’s country appears to support more competing bids, as seen by the positive and statistically significant coefficient on

WGI (in regressions 1 and 3).

We focus the next test on the emerging M&A markets in the world to isolate the effect of peripheral countries, where informational advantages are expected to increase the most due to social media. The qualifying criteria for this subsample are whether the target or acquirer were located outside any of the top ten M&A markets by volume across the full sample period. The top ten most active markets are: United States, United Kingdom, China, Japan, Canada, France, Hong Kong, Italy, Australia, and South Korea. The countries in the emerging market subsample are: Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, Finland, Germany, Greece, India, Indonesia, Israel, Jordan, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, Nigeria, Norway, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, and Turkey.

The top ten most active markets are assumed to be at the forefront of utilising technology to gain an informational edge in M&A transactions. Therefore, the incremental effect of social media on information acquisition may have been diluted. On the other hand,

Bekaert and Harvey (

2003) contend that emerging markets are not as informationally efficient as developed economies and that to achieve financial “liberalisation”, informational barriers must be broken down. This consequently increases stock market volatility and liquidity.

Lang et al. (

2003) find that improvements in an emerging market firm’s information environment (measured by analyst coverage and forecast accuracy) are positively related to firm valuations. With public information and networking capabilities now available in a form that is cheaper and more accessible than before, we expect the informational advantages to flow into the M&A market with a higher penetration than in the active markets. M&A professionals in the emerging markets would be able to harness the information advantages provided by social media, as it is radically improved from the existing public informational paradigm. The number of deals in the subsample is 8743 and the distribution of when social media rose to popularity across these countries ranges between 2006 and 2013, with significant clustering in 2007.

Table 8 shows the result of the probit regression. SocialMedia is negative and statistically significant for models 1 and 3. The marginal effect of SocialMedia is −23.5% on the probability of a competing bid given that a deal is announced in an active market. The effect is statistically significant at 10% when fixed effects are included in the model (see model 2). Without fixed effects but including all control variables (model 3), the marginal effect of social media on the probability of a competing is −20.8%, which is significant at the 5% level. This decrease in competing bids is contrary to the hypothesis and shows that informational effects due to social media have not contributed to greater M&A activity. These findings do not agree with

Larkin and Lyandres (

2017) who find that decreased search frictions, make it easier for target discovery and bid submission, leading to increased competition. Complementarity gains are positively related to competitive bidding and probability of target discovery, leading to more efficient allocation of resources. It is puzzling to see that social media suddenly exhibits an effect when the countries which should have been impacted the most are examined in isolation.

Next, we examine cross-border mergers in a separate subsample to test whether social media being popular in the acquiring or target country matters.

Both is a dummy variable that equals 1 if social media is popular in both the countries where the acquirer and target are domiciled. Due to geographic and cultural distances (such as language barriers and business etiquette), cross-border transactions in general experience a heightened level of information asymmetries (

Ahern et al. 2015). Social media should somewhat alleviate these barriers to accommodate free flowing information between the two markets. We use

Both as the main independent variable here because unless social media is popular in both countries there would not be an established bilateral social media link which the firms in either country could exploit to decrease search frictions and improve communication channels.

Table 9 reports the results of the probit regression on the full sample of cross-border deals with

Compete as the dependent variable and

Both as the main independent variable of interest.

Both is positive for all specifications and statistically different from zero for all models.

Table A4 in the

Appendix A reports the results of probit regressions run on a sample of cross-border deals where the target and acquirer countries are from the same geographic region. Again, the coefficient on

Both for this test is statistically significant at 10%.

6.4. Panel Fixed Effects Results

We now examine how the amount of cash paid has changed given the increase in popularity of social media across countries. We follow the same format as the analysis on bidding competition in the presentation of the results for consistency. We test what proportion of a transaction’s consideration is paid with cash before and after social media becomes popular and report our results in

Table 10. We find results from this regression with the

SocialMedia coefficient significant at 10%. Model 3 shows that once social media becomes popular in a country, the percentage of cash consideration decreases by 5.04%. Model 4 shows that deals involving private companies have higher cash components, suggesting higher information asymmetries in these deals.

As seen in the previous tables, competing bids have a positive relationship with the amount of cash paid in a deal. The coefficient on Index is negative and statistically significant, consistent with the idea that as stock markets experience downward pressure, firms will want to pay with cash (rather than their devalued stock).

Larger deal values exhibit lower cash proportions for payment and LBOs have a positive relationship with CashPaid where the transaction is typically financed with large amount of debt, i.e., cash. Cross-border transactions appear to consist of more cash as consideration, consistent with the theory of information asymmetry if we assume that cross-border deals do, in fact, exhibit more information barriers between targets and acquirers.

Table 11 reports the results of tests run on the subsample of ‘emerging market’ deals.

CashPaid is positive and highly statistically significant in models 3 and 4. That is, as social media becomes popular in a country, the percentage of the consideration paid in cash increases by 3.8% (in model 3). Again, contrary to the emerging market hypothesis, the results show that when excluding the most active M&A markets, informational advantages due to social media popularity has not lowered proportions of cash paid in transactions and the relationship between lower information acquisition costs and signalling of private valuations cannot be established.

Table 12 reports the results of the cross-border deals sample. Again, the main independent variable here is “

Both”. Panel A shows that

CashPaid is statistically significant in all model specifications at 10%. That is, the proportion of cash as consideration for a cross-border merger deal is marginally affected by whether or not social media is popular in both the acquiring and target firms’ respective countries for the full sample.

Table A5 in the

Appendix A shows the results of tests run on a cross-border subsample where deals are between firms in the same region. The coefficients on

Both are statistically significant at 10%, except for in model 1 where it is positive and highly statistically significant, contrary to H3.