STO vs. ICO: A Theory of Token Issues under Moral Hazard and Demand Uncertainty

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. The Model Description and Some Preliminaries

3.1. Utility Tokens

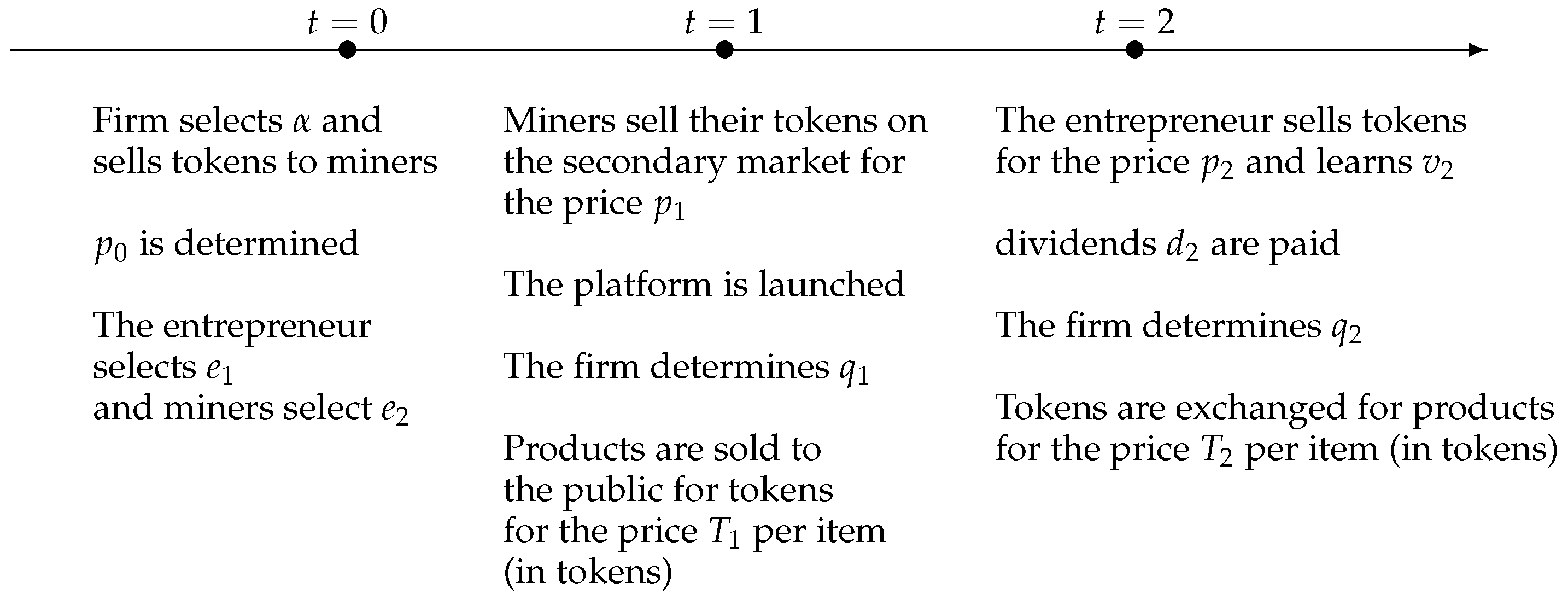

3.2. Security Tokens

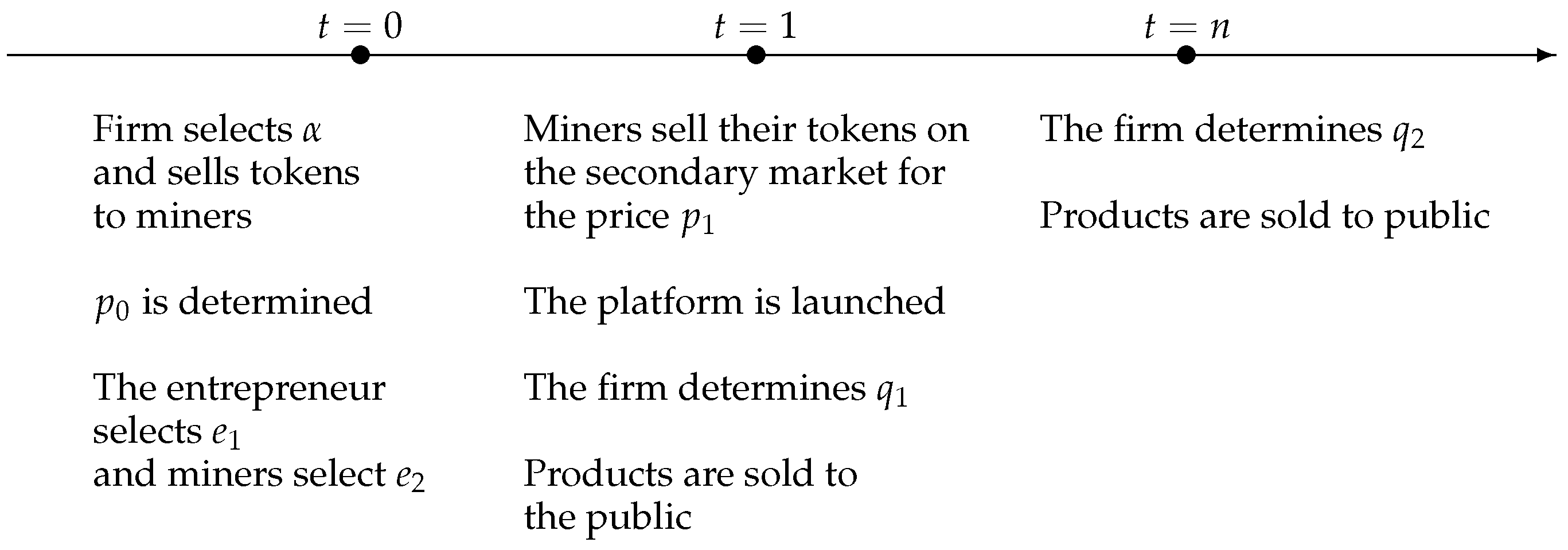

4. Product Development, Market Uncertainty and Incentives

4.1. Moral Hazard

4.2. Demand Uncertainty

4.3. Moral Hazard and Demand Uncertainty

5. Utility Tokens with Profit Rights

6. Implications

7. Model Extensions and Robustness

7.1. Cost of Fundraising and Platform Fees

7.2. Fund Limits

7.3. Multi-Period Model

7.4. Different Financing Strategies

7.5. Legal and Regulatory Issues

7.6. Cost of Production

7.7. Voting Rights

7.8. Asymmetric Information

7.9. Alternative Ways of Modelling Crowd Behaviour

7.10. Empirical Testing Strategies and Limitations

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

Appendix A.3

Appendix A.4

Appendix A.5

Appendix A.6

| 1 | In contrast to utility tokens, security tokens are regulated. The legal structures continue to evolve. In the US, for example, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) applies the Howey test to determine whether an asset qualifies as a security. Essentially, investments are considered securities if money is invested, the investment is expected to yield a profit, the money is invested in a common enterprise and any profit comes from the efforts of a promoter or third party SEC vs. Howey (1946). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | The empirical literature includes, among others, Boreiko and Risteski (2020); Masiak et al. (2020); Momtaz (2020) and Huang et al. (2020) See, for example, Kher et al. (2020) for a review. |

| 5 | We use the terms utility tokens with profit rights and hybrid tokens throughout the paper interchangeably. Note that the term hybrid tokens is quite popular in media articles and reports (see e.g., https://www.lawandblockchain.eu/the-case-for-hybrid-tokens/, accessed on 19 April 2021; https://medium.com/@calevanscrypto/the-hybrid-token-offering-95615239d639, accessed on 19 May 2021). |

| 6 | See, for example, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190711005651/en/, accessed on 19 April 2021. |

| 7 | See, for example, OECD (2019). For related research regarding security issues with smart tokens see, for example, Hancke et al. (2009). |

| 8 | |

| 9 | For a good discussion of economics of tokens including different examples of connections between the effort of independent miners and the success of the firm see, for example, Holden and Malani (2019) and Chod et al. (2019). They also discuss different reasons for why tokens are often used for compensating miners’ efforts and different types of relationship between the platform and miners (including e.g., PoW-“proof of work” and PoS-“proof of stakes”) and so forth. In particular they explain the advantages of PoS used by many firms such as Filecoin and so forth. Under PoS a platform requires miners to use tokens and so forth. Miners must stake some tokens and if they are not successful they cannot use these tokens, so miners have an incentive to work efficiently. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | See, for example, Oxera (2015) and Nadaulda et al. (2019). Regarding feedback feature of crowdsourcing see a review by Zhang et al. (2019). See Turulja and Bajgorić (2018) on the links between knowledge acquisition and innovation. See also Ballestar (2021). |

| 13 | Kukoin (2019), see also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pKlPiw943yI&t=34s, accessed on 19 April 2021. |

| 14 | See also Mella-Barral and Sabourian (2018). |

| 15 | In Section 7, we discuss the model’s assumptions including the ways of modelling moral hazard, demand for the product and so forth. |

| 16 | In Section 7, we discuss more possible strategies of financing. |

| 17 | They can be paid for with fiat money and a cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, Ether and so forth. |

| 18 | We do not consider the case where the firm issues tokens and runs out of business with cash. This type of managerial operational moral hazard is considered in for example, some papers on crowdfunding (see e.g., Strausz 2017) that is similar to the spirit of ICOs to some extent. In our case it would not be an optimal strategy for the firm since it will not get any cash from selling tokens in future periods (the market participants would not buy tokens from the firm that “cheated” on them previously). An interpretation would be a tit-for-tat repeated game equilibrium failure (see e.g., Hargreaves-Heap and Varoufakis 2004). This is clearly not optimal. Any production decision that does not maximize the number of tokens received from selling goods (and respectively the value of tokens received) is not optimal either. One can show that any q that is different from leads to a smaller value of tokens sold in long-term equilibrium using Equations (2)–(6). |

| 19 | Similar ideas have been discussed in the literature on reward-based crowdfunding where the participants should be incentivized to participate in pre-sales, for example, the pre-sale price should not exceed future spot price. For a discussion see, for example, Belleflamme et al. (2014); Miglo (2019) or Miglo (2020b). |

| 20 | Recall that the token velocity is equal to one period. This is chosen for simplicity. Qualitatively, the results will not change if a different velocity is chosen. For the effect of velocity on ICOs, see, for example, Holden and Malani (2019). |

| 21 | Note that in monetary economics, for example, it is common to use the expected velocity of money (see e.g., Lucas 1988; Ireland 1996; Alvarez et al. 2001; Cochrane 2005). As was mentioned previously the velocity of tokens was studied in Holden and Malani (2019). |

| 22 | In particular we discuss a model variation that does not have a global demand and does not have an expected velocity of tokens and where instead the redemption of value of tokens is introduced and where each tokenholder has two strategies in each period (redeem tokens or continue to hold them). |

| 23 | Since in a digital economy the firm inflows includes both tokens and cash and since the regulation is not yet perfectly developed there exists a variety of different interpretations of a firm’s profit (see e.g., Boyanov 2019). One we consider here is consistent with the spirit of financing literature although different ways of modelling are possible, for example, tokenholders’ profit can be calculated as a fraction of money received from reselling tokens (this is not exactly in the spirit of traditional literature since money received from selling shares during IPO for example are not considered the firm profit although it is a form of firm capital). Note also that the firm can transfer cash between periods with no costs (e.g., invests in bonds or borrow funds etc.). So this mitigates the problem of potential accounting differences between firm cash and firm profit in each period. Note that none of these assumptions are crucial. The results hold under different ways of modelling. |

| 24 | Most charge lump sum, see, for example, https://medium.com/@jaronlukas/the-leading-security-token-issuance-platforms-a-summary-comparison-ac8d42290f98, accessed on 19 April 2021, https://www.investopedia.com/news/how-much-does-it-cost-list-ico-token/, accessed on 19 May 2021, http://chainplus.one/blog/step-by-step-how-to-launch-an-sto/#:~:text=Simply%20,speaking%2C%20the%20cost%20for,to%20costs%20being%20significantly%%20higher, accessed on 19 April 2021. |

| 25 | See, for example, https://www.pwc.ch/en/publications/2019/ch-PwC-Strategy&-ICO-Report-Summer-2019.pdf, accessed on 19 April 2021. https://www.quora.com/Does-the-setup-for-an-STO-cost-higher-than-an-ICO-If-so-why-are-people-gravitating-to-security-token-offerings, accessed on 19 May 2021. |

| 26 | See, for example, https://dailyfintech.com/2019/08/27/hybrid-security-tokens-what-are-they-and-what-are-they-not/, accessed on 19 April 2021. |

| 27 | In a model with infinite number of periods that we discuss later, the firm value is about where is the discount rate. So determines the difference between firm total earnings and its earnings in the first period. has a similar interpetation in our basic model (see e.g., Lemma 1). So, if we take the range of values for between 0.25% and 100%, it gives us approximately the range of values for s used in Table 1. |

| 28 | For example, an ICO cost is estimated as about $500,000 (see e.g., https://www.bitcoinmarketjournal.com/launching-an-ico/, accessed on 19 April 2021) and an STO cost (in general it is similar to ICO but includes the registration fees and cost) is estimated as about $1,000,000 (see e.g., https://www.finyear.com/Cost-Benefits-of-STO-vs-Private-Placement_a40021.html, accessed on 19 April 2021. The difference equals $500,000 which is about 1.2% of the STO value. |

| 29 | See e.g., https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/biz/archives/2019/06/28/2003717700, accessed on 19 April 2021. |

| 30 | See, for example, PwC/Strategy& (2020). |

| 31 | See e.g., https://otonomos.com/2020/01/security-token-regulations-demystified/, accessed on 19 April 2021. |

| 32 | |

| 33 | For a review of capital structure literature see, among others, Harris and Raviv (1991) or Miglo (2011). For a traditional analysis of the capital structure of internet companies see, for example, Miglo et al. (2014). |

| 34 | For an alternative model of mixed token finance see Gan et al. (2021). |

| 35 | See https://blog.polymath.network/minthealth-and-polymath-bring-the-first-healthcare-security-token-to-revolutionize-healthcare-a36884f17e4e, accessed on 19 April 2021; https://hackernoon.com/how-to-do-an-sto-an-exclusive-interview-with-the-founder-of-minthealth-ba24be0c6025, accessed on 19 May 2021. |

| 36 | See https://www.coindesk.com/nba-players-contract-tokenization-plan-can-move-forward-reports, accessed on 19 May 2021. |

| 37 | For similar ideas see e.g., https://multicoin.capital/2019/05/24/the-unbundling-of-ethereum/, accessed on 19 May 2021, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/unbundling-rebundling-payments-aaron-mcpherson, accessed on 19 May 2021. |

| 38 | IEO (initial exchange offering) is a new form of fundraising where tokens are offered through exchanges. For more details see, for example, Miglo (2020a). See also https://hackernoon.com/can-the-combination-of-sto-ieo-become-the-new-step-in-crowdfunding-evolution-y943m42rj accessed on 19 April 2021. |

| 39 | Kik-messenger, https://www.coindesk.com/the-8-biggest-bombshells-from-the-secs-kik-ico-lawsuit, accessed on 19 May 2021. |

| 40 | See e.g., https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/kik-in-the-butt-court-decision-against-52403/, accessed on 19 May 2021. |

| 41 | |

| 42 | Holden and Malani (2019) analyze the role of the velocity of tokens. |

| 43 | Recall that the token velocity is one year. In Section 6 we dsicuss different extensions related to this assumtpion. |

References

- Adhami, Saman, Giancarlo Giudici, and Stefano Martinazzi. 2018. Why do businesses go crypto? An empirical analysis of Initial Coin Offerings. Journal of Economics and Business 100: 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchian, Armen, and Harold Demsetz. 1972. Production, Information Costs, and Economic Organization. American Economic Review 62: 777–95. [Google Scholar]

- Altaleb, Abdullah, and Andrew Gravell. 2019. An Empirical Investigation of Effort Estimation in Mobile Apps Using Agile Development Process. Journal of Software 14: 356–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, Fernando, Robert E. Lucas, and Warren E. Weber. 2001. Interest Rates and Inflation. American Economic Review 91: 219–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amano, Tomomichi, Andrew Rhodes, and Stephan Seiler. 2019. Large-Scale Demand Estimation with Search Data. Working Paper. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3214812 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Amsden, Ryan, and Denis Schweizer. 2018. Are Blockchain Crowdsales the New “Gold Rush”? Success Determinants of Initial Coin Offerings. Working Paper. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3163849 (accessed on 12 December 2018).

- Ang, James S., Rebel Cole, and James Wuh Lin. 2000. Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. The Journal of Finance 55: 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ante, Lennart, and Ingo Fiedler. 2019. Cheap Signals in Security Token Offerings (STOs). BRL Working Paper Series No. 1. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3356303 (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Ante, Lennart, Philipp Sandner, and Ingo Fiedler. 2018. Blockchain-based ICOs: Pure Hype or the Dawn of a New Era of Startup Financing? Journal of Risk and Financial Management 11: 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakos, Yannis, and Hanna Halaburda. 2018. The Role of Cryptographic Tokens and ICOs in Fostering Platform Adoption. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3207777 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Ballestar, María T. 2021. Segmenting the Future of E-Commerce, One Step at a Time. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 16: i–iii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, Saleem, and Ponnurangam Dhavachelvan. 2010. Analysis of Empirical Software Effort Estimation Models. International Journal of Computer Science and Information Security 7: 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bellavitis, Cristiano, Christian Fisch, and Johan Wiklund. 2020. A comprehensive review of the global development of initial coin offerings (ICOs) and their regulation. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 15: e00213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleflamme, Paul, Thomas Lambertz, and Armin Schwienbacher. 2014. Crowdfunding: Tapping the Right Crowd. Journal of Business Venturing: Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurial Finance, Innovation and Regional Development 29: 585–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bitler, Marianne, Tobias J. Moskowitz, and Annette Vissing-Jørgensen. 2005. Testing Agency Theory with Entrepreneur Effort and Wealth. The Journal of Finance 60: 539–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blockstate Global STO Study. 2019. Available online: https://blockstate.com/global-sto-study-en/ (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Bolton, Patrick, and David Scharfstein. 1990. A Theory of Predation Based on Agency Problems in Financial Contracting. American Economic Review 80: 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Boreiko, Dmitri, and Dimche Risteski. 2020. Serial and large investors in initial coin offerings. Small Business Economics. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boyanov, Borislav. 2019. Approaches for Accounting and Financial Reporting of Initial Coin Offering (ICO). Paper presented at 15th International Conference of ASECU, Sofia, Bulgaria, September 26–27; pp. 74–83. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340933834_Approaches_for_Accounting_and_Financial_Reporting_of_Initial_Coin_Offering_ICO (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Brander, James, and Tracy R. Lewis. 1986. Oligopoly and Financial Structure: The Limited Liability Effect. American Economic Review 76: 956–70. [Google Scholar]

- Canidio, Andrea. 2018. Financial Incentives for Open Source Development: The Case of Blockchain. MPRA Working Paper. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/103804/1/MPRA_paper_103804.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Catalini, Christian, and Joshua S. Gans. 2018. Initial Coin Offerings and the Value of Crypto Tokens. NBER Working Paper 24418. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w24418 (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Chemla, Gilles, and Katrin Tinn. 2019. Learning Through Crowdfunding. Management Science 66: 1783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Long, Lin William Cong, and Yizhou Xiao. 2021. A Brief Introduction to Blockchain Economics. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company, chp. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chod, Jiri, and Evgeny Lyandres. 2019. A Theory of ICOs: Diversification, Agency, and Information Asymmetry. Working Paper. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3159528 (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Chod, Jiri, Nikolaos Trichakis, and Alex Yang. 2019. Platform Tokenization: Financing, Governance, and Moral Hazard. Working Paper. Available online: http://www.econ.ntu.edu.tw/uploads/asset/data/607fc66648b8a10278021ae7/HKBU_1100429.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Cochrane, John H. 2005. Money as Stock. Journal of Monetary Economics 52: 501–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coinschedule. 2018. Cryptocurrency ICO Stats. Available online: https://www.coinschedule.com/stats.html (accessed on 9 December 2018).

- Cong, Lin William, Ye Li, and Neng Wang. 2018. Tokenomics: Dynamic Adoption and Valuation. Working Paper. Available online: https://bfi.uchicago.edu/working-paper/tokenomics-dynamic-adoption-and-valuation/ (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Coppejans, Mark, Donna Gilleskie, Holger Sieg, and Koleman Strumpf. 2007. Consumer Demand Under Price Uncertainty: Empirical Evidence from the Market for Cigarettes. The Review of Economics and Statistics 89: 510–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Sanjiv R. 2019. The Future of FinTech. Financial Management 48: 981–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demichelis, Stefano, and Ornella Tarola. 2006. Capacity expansion and dynamic monopoly pricing. Research in Economics 60: 169–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellman, Matthew, and Sjaak Hurkens. 2017. A Theory of Crowdfunding a Mechanism Design Approach with Demand Uncertainty and Moral Hazard: Comment. Available online: http://www.iae.csic.es/investigatorsMaterial/a1812160140sp40258.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Gan, Rowena, Gerry Tsoukalas, and Serguei Netessine. 2020. Initial Coin Offerings, Speculation, and Asset Tokenization. Management Science 67: 914–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Rowena, Gerry Tsoukalas, and Serguei Netessine. 2021. To Infinity and Beyond: Financing Platforms with Uncapped Crypto Tokens. SMU Cox School of Business Research Paper No. 21-03. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3776411 (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Garicano, Luis, Adam Meirowitz, and Luis Rayo. 2017. Information Sharing and Moral Hazard in Teams. Working Paper. Available online: https://d30i16bbj53pdg.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/14_Rayo_Information-Sharing-and-Moral-Hazard-in-Teams.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Garratt, Rodney, and Maarten R. C. van Oordt. 2019. Entrepreneurial Incentives and the Role of Initial Coin Offerings. Staff Working Paper. Ottawa: Bank of Canada. Available online: https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2019/05/staff-working-paper-2019-18/ (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Graham, John R., and Campbell Harvey. 2001. The theory and practice of corporate finance: Evidence from the field. Journal of Financial Economics 60: 187–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryglewicz, Sebastian, Simon Mayer, and Erwan Morellec. 2020. Optimal Financing with Tokens. Working Paper. Available online: https://personal.eur.nl/gryglewicz/files/tokens.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Hall, Bronwyn H. 2009. The Financing of Innovative Firms. EIB Papers 14: 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancke, Gerhard, Keith E. Mayes, and Konstantinos Markantonakis. 2009. Confidence in smart token proximity: Relay attacks revisited. Computers & Security 28: 615–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves-Heap, Shaun P., and Yanis Varoufakis. 2004. Game Theory: A Critical Text. London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-25094-8. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Milton, and Artur Raviv. 1991. The Theory of Capital Structure. Journal of Finance 46: 297–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, Richard, and A. Malani. 2019. The ICO Paradox, Transaction Costs, Token Velocity, and Token Value. NBER Working Papers 26265. Cambridge: NEBR. [Google Scholar]

- Holmström, Bengt. 1982. Moral Hazard in Teams. Bell Journal of Economics 13: 324–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, Sabrina T., Marina Niessner, and David Yermack. 2018. Initial Coin Offerings: Financing Growth with Cryptocurrency Token Sales. NBER Working Papers 24774. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Winifred, Michele Meoli, and Silvio Vismara. 2020. The geography of initial coin offerings. Small Business Economics 55: 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, Peter N. 1996. The Role of Countercyclical Monetary Policy. Journal of Political Economy 104: 704–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, Jarosław, Przemysław Kazienkoa, Jarosław Watróbski, Anna Lewandowska, Paweł Ziemba, and Magdalena Zioło. 2016. Fuzzy multi-objective modeling of effectiveness and user experience in online advertising. Expert Systems with Applications 65: 315–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kher, Romi, Siri Terjesen, and Chen Liu. 2020. Blockchain, Bitcoin, and ICOs: A review and research agenda. Small Business Economics. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukoin. 2019. Michael AMA @ TRON Community: Exchanges Are Naturally for Staking Services. Available online: https://www.kucoin.com/news/en-michael-ama-tron-community-exchanges-are-naturally-for-staking-services (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Lambert, Thomas, Daniel Liebau, and Peter Roosenboom. 2020. Security Token Offerings. Working Paper. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342419787_Security_Token_Offerings (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Lee, Jeongmin, and Christine A. Parlour. 2020. Consumers as Financiers: Crowdfunding, Initial Coin Offerings and Consumer Surplus. Working Paper. Available online: https://www.chapman.edu/research/institutes-and-centers/economic-science-institute/_files/ifree-papers-and-photos/parlour-lee-consumers-as-financiers-2019.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Levy, Zeeva. 1990. Estimating the Effort in the Early Stages of Software Development. Ph.D. Thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jiasun, and William Mann. 2018. Digital Tokens and Platform Building. Working Paper. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/309e/f98741d5da2003df8317fd605e1ac83d6fb9.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Li, Li, and Zixuan Wang. 2019. How does capital structure change product-market competitiveness? Evidence from Chinese firms. PLoS ONE 14: e0210618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, Robert E., Jr. 1988. Money Demand in the United States: A Quantitative Review. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 29: 169–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiak, Christian, Joern H. Block, Tobias Masiak, Matthias Neuenkirch, and Katja N. Pielen. 2020. Initial coin offerings (ICOs): Market cycles and relationship with bitcoin and ether. Small Business Economics 55: 1113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mella-Barral, Pierre, and Hamid Sabourian. 2018. Sequel Firm Creation and Moral Hazard in Teams. Working Paper. Available online: https://www.law.northwestern.edu/research-faculty/clbe/events/innovation/documents/mella-barral_seqone_03.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Miglo, Anton. 2011. Trade-off, Pecking order, Signalling, and Market Timing Models. In Capital Structure and Corporate Financing Decisions: Theory, Evidence, and Practice. Edited by Gerald S. Martin and H. Kent Baker. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Miglo, Anton. 2019. STO vs. ICO: A Theory of Token Issues Under Moral Hazard and Demand Uncertainty. Working Paper. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3449980 (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Miglo, Anton. 2020. Choice between IEO and ICO: Speed vs. Liquidity vs. Risk. Working Paper. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3561439 (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Miglo, Anton. 2020. Crowdfunding in a Competitve Environment. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13: 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miglo, Anton. 2020. Crowdfunding under Market Feedback, Asymmetric Information and Overconfident Entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship Research Journal. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miglo, Anton. 2020. ICO vs. Equity Financing under Imperfect, Complex and Asymmetric Information. Working Paper. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3539017 (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Miglo, Anton. 2021. Theories of Crowdfundign and Token Issues: A Review. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Miglo, Anton, and Victor Miglo. 2019. Market Imperfections and Crowdfunding. Small Business Economics 53: 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miglo, Anton, Zhenting Lee, and Shuting Liang. 2014. Capital Structure of Internet Companies: Case Study. Journal of Internet Commerce 13: 253–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, Franco, and Merton Miller. 1958. The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment. American Economic Review 48: 261–97. [Google Scholar]

- Momtaz, Paul P. 2020. Initial Coin Offerings, Asymmetric Information, and Loyal CEOs. Small Business Economics. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Stewart C., and Nicholas S. Majluf. 1984. Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics 13: 187–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nadaulda, Taylor D., Berk A. Sensoy, Keith Vorkink, and Michael S. Weisbach. 2019. The liquidity cost of private equity investments: Evidence from secondary market transactions. Journal of Financial Economics 132: 158–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2019. Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) for SME Financing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/finance/initial-coin-offerings-forsmefinancing.htm (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Oxera. 2015. Crowdfunding from An Investor Perspective. Prepared for the European Commission Financial Services User Group. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/file_import/160503-study-crowdfunding-investor-perspective_en_0.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Protocol Labs, Inc. 2017. Filecoin Primer. Available online: https://ipfs.io/ipfs/QmWimYyZHzChb35EYojGduWHBdhf9SD5NHqf8MjZ4n3Qrr/Filecoin-Primer.7-25.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- PwC/Strategy&. 2020. 6th ICO/STO Report. Available online: https://www.pwc.ch/en/publications/2020/Strategy&_ICO_STO_Study_Version_Spring_2020.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Schwienbacher, Armin. 2018. Entrepreneurial Risk-taking in Crowdfunding Campaigns. Small Business Economics 51: 843–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEC vs. Howey. 1946. SEC v. WJ Howey Co., 328 U.S. 293, 66 S.Ct. 1100, 90 L. Ed. 1244. Available online: https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/328/293 (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Stiglitz, Josef, and Andrew Weiss. 1981. Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. American Economic Review 73: 393–409. [Google Scholar]

- Strausz, Roland. 2017. Crowdfunding, Demand Uncertainty, and Moral Hazard—A Mechanism Design Approach. American Economic Review 107: 1430–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turulja, Lejla, and Nijaz Bajgorić. 2018. Knowledge Acquisition, Knowledge Application, and Innovation Towards the Ability to Adapt to Change. International Journal of Knowledge Management 14: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Luyao, Hong Fan, and Tianren Gong. 2018. The Consumer Demand Estimating and Purchasing Strategies Optimizing of FMCG Retailers Based on Geographic Methods. Sustainability 10: 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wątróbski, Jarosław, Jarosław Jankowski, and Paweł Ziemba. 2016. Multistage Performance Modelling in Digital Marketing Management. Economics and Sociology 9: 101–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, Joseph T. 1995. Financial and Industrial Structure with Agency. The Review of Financial Studies 8: 431–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Karen E. 2015. Policy Lessons from Financing Innovative Firms. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers No. 24. Paris: OECD Publishing, Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5js03z8zrh9p-en (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Zhang, Xuefeng, Mingshuang Chen, and Guanqun Ji. 2019. Factors influencing the crowd participation in knowledge-intensive crowdsourcing. Paper presented at 4th International Conference on Crowd Science and Engineering, Jinan, China, October 18–21. [Google Scholar]

| (a) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Demand | |||||

| Market scale | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 |

| 20 | 315.63 | 5050.03 | 80,800.50 | 1,292,808.00 | 20,684,928.00 |

| 10 | 20.31 | 325.03 | 5200.50 | 83,208.00 | 1,331,328.00 |

| 5 | 1.42 | 22.69 | 363.00 | 5808.00 | 92,928.00 |

| 1 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 3.00 | 48.00 | 768.00 |

| (b) | |||||

| Initial Demand | |||||

| Market scale | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 |

| 20 | 471.10 | 7537.55 | 120,600.75 | 1,929,612.00 | 30,873,792.00 |

| 10 | 29.89 | 478.17 | 7650.75 | 122,412.00 | 1,958,592.00 |

| 5 | 1.98 | 31.69 | 507.00 | 8112.00 | 129,792.00 |

| 1 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 3.00 | 48.00 | 768.00 |

| (c) | |||||

| Initial Demand | |||||

| Market scale | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 |

| 20 | 155.47 | 2487.52 | 39,800.25 | 636,804.00 | 10,188,864.00 |

| 10 | 9.57 | 153.14 | 2450.25 | 39,204.00 | 627,264.00 |

| 5 | 0.56 | 9.00 | 144.00 | 2304.00 | 36,864.00 |

| 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 00.00 | 4800.00 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miglo, A. STO vs. ICO: A Theory of Token Issues under Moral Hazard and Demand Uncertainty. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060232

Miglo A. STO vs. ICO: A Theory of Token Issues under Moral Hazard and Demand Uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2021; 14(6):232. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060232

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiglo, Anton. 2021. "STO vs. ICO: A Theory of Token Issues under Moral Hazard and Demand Uncertainty" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 6: 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060232

APA StyleMiglo, A. (2021). STO vs. ICO: A Theory of Token Issues under Moral Hazard and Demand Uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(6), 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060232