The Effect of Short-Sale Restrictions on Corporate Managers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Hypothesis Development

3. Data and Variable Construction

3.1. Value-Reducing Acquisition Attempts

| Number of Observations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-SHO | SHO | Post-SHO | |

| All acquisition attempts in SDC | 5610 | 4419 | 4643 |

| Less: missing data in SDC9 | 2428 | 1916 | 2331 |

| Less: missing data in CRSP | 15 | 6 | 8 |

| Less: missing data in Compustat | 279 | 247 | 211 |

| Less: acquirer is not designated as a pilot or nonpilot firm | 891 | 819 | 990 |

| Less: acquirer owns more than 50% of target at announcement | 29 | 13 | 13 |

| Less: acquirer seeks to own less than 100% of target | 164 | 89 | 95 |

| Less: transaction value less than USD 100 million | 1232 | 775 | 539 |

| Less: acquisition attempt is not value-reducing | 293 | 295 | 238 |

| Value-reducing acquisition attempts | 279 | 259 | 218 |

3.2. Key Independent Variables

3.3. Control Variables

3.4. Descriptive Statistics

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Univariate Analysis of Abandonments of Corporate Acquisition Attempts

4.2. Linear Probability Regressions of Acquisition Attempt Abandonments

4.2.1. Acquiring Firm’s CAR

4.2.2. Acquiring Firm’s CAR and Regulation SHO

4.3. Acquisition Characteristics

4.3.1. Focused vs. Diversifying Acquisitions

4.3.2. High-Tech vs. Non-High-Tech Target Firms

4.4. Corporate Governance of Acquiring Firms

5. Robustness

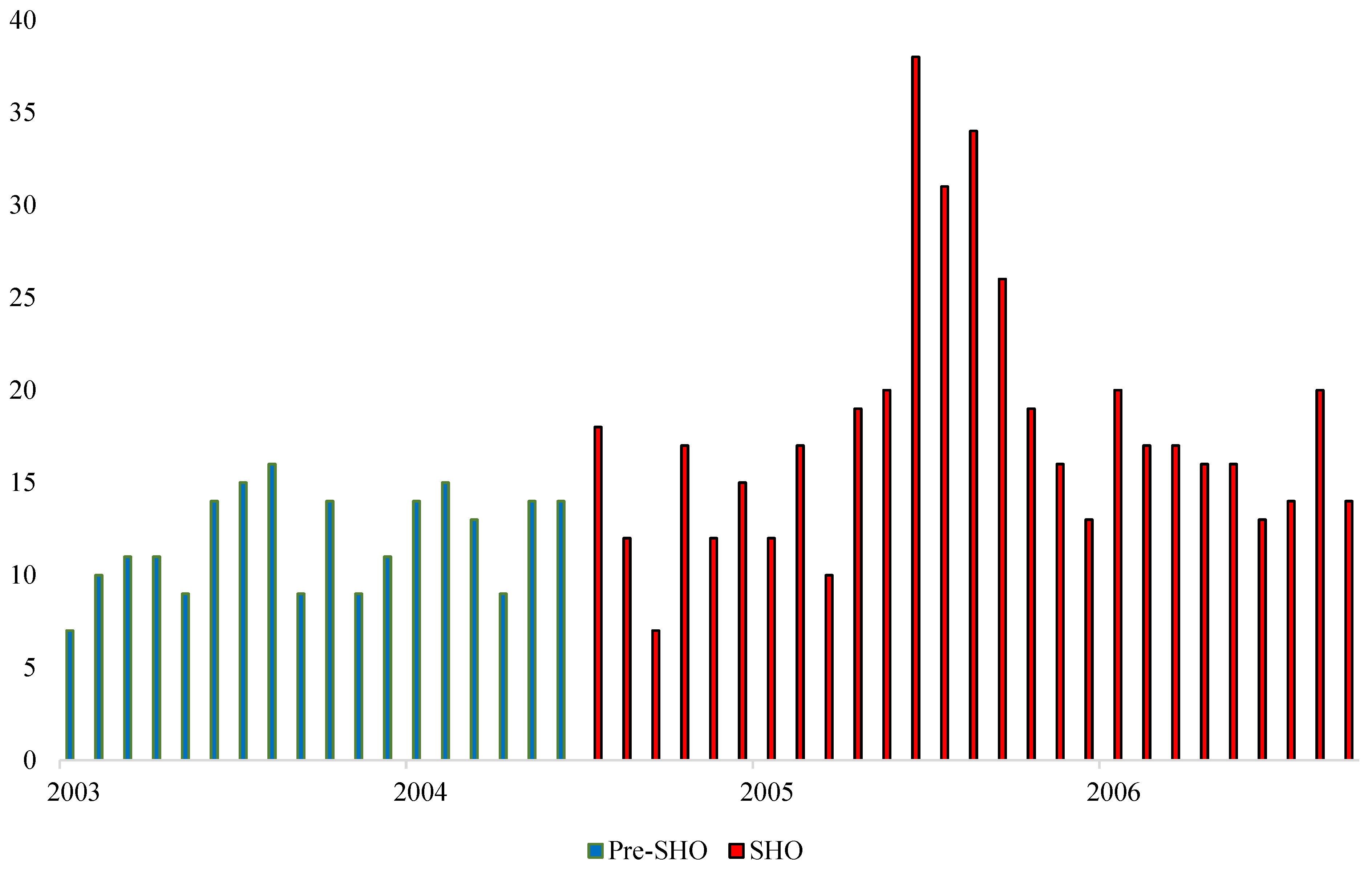

5.1. Delayed Response in Stock Prices Due to Impeded Short Sellers

5.2. Post-Announcement Drift

5.3. Benchmark for Value-Reducing Acquisitions

5.4. Acquirers Repeatedly Abandoning Acquisition Attempts

5.5. Other Robustness Tests

6. Using Regulation SHO as an Exogenous Shock

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Variable Definitions

| Variable | Definition |

| CAR | Cumulative abnormal return over the (−1, +1) interval surrounding announcements of an acquisition using the market model where the announcement dates are from SDC. |

| Abandonment | One for abandoned acquisition attempts and zero for completed acquisition attempts, as reported by SDC. |

| Compete Dummy | One for acquisition attempts with the emergence of a third party who launches an offer to the same target firm while the original acquisition attempt is pending and zero otherwise, as reported by SDC. |

| Defense Dummy | One for acquisition attempts in which the target firm undertakes defensive tactics to fend off the acquisition attempt and zero otherwise, as reported by SDC. |

| Definitive Agreement Dummy | One for acquisition attempts in which the finalized terms of the deal are agreed upon prior to or on the acquisition announcement date and zero otherwise, as reported by SDC. |

| Diversifying Acquisitions | Acquisition attempts in which the target and acquiring firm are not in the same Fama–French 17 industry. |

| E-Index | The Entrenchment index of Bebchuk et al. (2009) in the year prior to the acquisition announcement. |

| Focused Acquisitions | Acquisition attempts in which the target and acquiring firm are in the same Fama–French 17 industry. |

| Hostile Dummy | One for acquisition attempts in which the “attitude” of the proposed acquisition is hostile and zero otherwise, as reported by SDC. |

| High-Tech Target | One for acquisition attempts in which the target firm is categorized as high-tech and the acquirer has a different SIC Code than the target and zero otherwise, as reported by SDC. |

| Lockup Dummy | One for acquisition attempts including a lockup of target shares in which the potential acquirer is granted an option to purchase shares at a fixed price even if a competing offer emerges and zero otherwise, as reported by SDC. |

| Ln(Market Cap) | The natural log of the acquirer’s market value of equity (in millions of dollars) on the 43rd trading day prior to the announcement day of the acquisition attempt. |

| Same-State HQ Dummy | One for acquisition attempts where the acquirer and target firms are incorporated in the same state and zero otherwise. |

| Tender Offer Dummy | One for acquisition attempts structured as a tender offer and zero otherwise, as reported by SDC. |

| Pre-SHO | One for acquisition attempts announced between 1 January 2002 and 1 May 2005 (inclusive) and zero otherwise. |

| Pilot | One for acquisition attempts where the acquirer was a pilot firm in Regulation SHO and zero otherwise. |

| SHO | One for acquisition attempts announced between 2 May 2005 and 6 August 2007 (inclusive) and zero otherwise. |

| Post-SHO | One for acquisition attempts announced between 7 August 2007 and 31 December 2010 (inclusive) and zero otherwise. |

| Stock Dummy | One for acquisition attempts financed or partially financed by the acquirer’s common stock and zero otherwise. |

| Termination Fee Dummy | One for acquisition attempts that include termination fees that the potential acquirer must pay to the target if the transaction is abandoned and zero otherwise, as reported by SDC. |

Appendix B. Institutional Background

Notes

| 1 | For papers on the informativeness of short sellers trades, see Miller (1977), Diamond and Verrecchia (1987), Senchack and Starks (1993), Desai et al. (2002), Duffie et al. (2002), Asquith et al. (2005), Bris et al. (2007), Boehmer et al. (2008), Saffi and Sigurdsson (2011), Engelberg et al. (2012), Boehmer and Wu (2013), Curtis and Fargher (2014), Akbas et al. (2017), and Hwang et al. (2019), among others. For papers on managers learning from prices, see Gilchrist et al. (2005), Grullon et al. (2015), He et al. (2023), among others. |

| 2 | “Elon Musk: The Architect of Tomorrow”, Neil Strauss, 15 November 2017. Similar sentiments include, for example, Jamie Dimon’s (CEO of JP Morgan), discussion of the role of short sellers in the downfall of Bear Stearns in “S.E.C. Unveils Measures to Limit Short-Selling”, Jenny Anderson, 16 July 2008 or Patrick Byrne’s (CEO of Overstock) allegation against short sellers in “Overstock’s Phantom Menace”, Bethany McLean, 1 November 2005. |

| 3 | (Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) 2007), Economic analysis of the short sale price restrictions under the regulation SHO pilot, Office of Economic Analysis. |

| 4 | We define value-reducing acquisition attempts as those that are accompanied by a negative stock price reaction at the announcement of the deal as measured by the acquiring firm’s 3-day announcement period CAR. |

| 5 | See, for example, Luo (2005), Chen et al. (2007), Kau et al. (2008), Masulis et al. (2009), and Liu and McConnell (2013) who report that managers are more likely to abandon acquisition attempts the lower the stock returns of the acquirer at the announcement of the potential acquisition. |

| 6 | See Bebchuk et al. (2009) for further discussion on the E-Index. |

| 7 | See, for example, Boehmer and Wu (2013), Saffi and Sigurdsson (2011), Massa et al. (2015), Bris et al. (2007), Beber and Pagano (2013), and Charoenrook and Daouk (2009) among others. |

| 8 | The SEC initially published a list of 986 pilot stocks (available at https://www.sec.gov/rules/other/34-50104.htm) on 28 July 2004. The list was later updated to 948 pilot stocks to account for business combinations, permanent delistings, and other corporate events (available at https://www.sec.gov/spotlight/shopilot.htm (accessed on 13 November 2023)). For robustness, we re-estimate our models using the updated list of pilot stocks and find quantitatively similar results. These results are reported in the Supplementary Materials. |

| 9 | Missing variables include the percentage of target shares that the acquirer owns prior to the proposed acquisition, percentage of shares sought by the acquirer, transaction value, and the final transaction status (i.e., completed or withdrawn). |

| 10 | Following Fang et al. (2016), who also use Regulation SHO as a quasi-natural experiment, we limit our sample from 2002 (inclusive) to 2010 (inclusive). This allows us to compare the results from the three-year window when Regulation SHO was active to a three-year window prior to and post the program. |

| 11 | See, for example, Henry (2004), Liu and McConnell (2013), Chen et al. (2015), Becht et al. (2016), and Bereskin et al. (2018) among others. |

| 12 | See note 5 above. |

| 13 | We are limited in our selection of variables to proxy for the opacity of the target firm by their availability of variables for non-listed firms. |

| 14 | The causal chain approach sequences the results such that first order effects are tested first. The Romano and Wolf (2005) procedure is then performed resulting in updated critical values with which the second order effects are tested. This continues to the third order effects and so on until all effects have been tested. For Regulation SHO, variables related to the price formation process (i.e., manager’s perception of short sellers’ involvement) are considered second order outcomes. |

| 15 | “The busted randomization went unnoticed by all prior researchers, including the OEA. Indeed, Chester Spatt, the then-SEC Chief Economist who oversaw the experiment, told us that he was not aware that the SEC had created a partly treated group from the original controls”. Litvak et al. (2020). |

| 16 | http://www.sec.gov/rules/other/34-50104.htm (accessed on 12 November 2023). |

| 17 | See Morgenson, Gretchen. “Why the roller coaster seems wilder”, The New York Times. 26 August 2007. |

| 18 | See Meckler, Laura and Scannell, Kara. “McCain Says Cox Should Be Fired as SEC Chief Amid ‘Casino’ Markets” The Wall Street Journal. 18 September 2008. |

| 19 | See Carney, John. “Bring Back the Uptick Rule?” Business Insider. 18 November 2008. |

| 20 | See https://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-26.htm (accessed on 12 November 2023) for the SEC’s press release announcing the adoption of the alternative uptick rule. |

References

- Aggarwal, Rajesh K., and Mufaddal. H. Baxamusa. 2013. Unrelated acquisitions. Paper presented at the American Finance Association Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, January 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Akbas, Ferhat, Ekkehart Boehmer, Bilal Erturk, and Sorin Sorescu. 2017. Short interest, returns, and fundamentals. Financial Management 46: 455–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asquith, Paul, Parag A. Pathak, and Jay R. Ritter. 2005. Short interest, institutional ownership, and stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics 78: 243–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Thomas W., and Michael L. Lemmon. 2003. Breaking up is hard to do? An analysis of termination fee provisions and merger outcomes. Journal of Financial Economics 69: 469–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebchuk, Lucian, Alma Cohen, and Allen Ferrell. 2009. What matters in corporate governance? The Review of Financial Studies 22: 783–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beber, Alessandro, and Marco Pagano. 2013. Short-selling bans around the world: Evidence from the 2007–09 crisis. The Journal of Finance 68: 343–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becht, Marco, Andrea Polo, and Stefano Rossi. 2016. Does mandatory shareholder voting prevent bad acquisitions? The Review of Financial Studies 29: 3035–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benou, Georgina, and Jeff Madura. 2005. High-tech acquisitions, firm specific characteristics and the role of investment bank advisors. The Journal of High Technology Management Research 16: 101–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereskin, Fred, Seong K. Byun, Micah S. Officer, and Jong-Min Oh. 2018. The effect of cultural similarity on mergers and acquisitions: Evidence from corporate social responsibility. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 53: 1995–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, Ekkehart, and Julie Wu. 2013. Short selling and the price discovery process. The Review of Financial Studies 26: 287–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, Ekkehart, Charles M. Jones, and Xiaoyan Zhang. 2008. Which shorts are informed? The Journal of Finance 63: 491–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bris, Arturo, William N. Goetzmann, and Ning Zhu. 2007. Efficiency and the bear: Short sales and markets around the world. The Journal of Finance 62: 1029–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, Timothy R. 2001. Locking out rival bidders: The use of lockup options in corporate mergers. Journal of Financial Economics 60: 103–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Eric C., Tse-Chun Lin, and Xiaorong Ma. 2019. Does short-selling threat discipline managers in mergers and acquisitions decisions? Journal of Accounting and Economics 68: 101223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenrook, Anchada Aida, and Hazem Daouk. 2009. A Study of Market-Wide Short-Selling Restrictions. Working Paper. Ithaca: Cornell University, Department of Applied Economics and Management. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Tao, Jarrad Harford, and Chen Lin. 2015. Do analysts matter for governance? Evidence from natural experiments. Journal of Financial Economics 115: 383–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Xia, Jarrad Harford, and Kai Li. 2007. Monitoring: Which institutions matter? Journal of Financial Economics 86: 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, Asher, and Neil L. Fargher. 2014. Does short selling amplify price declines or align stocks with their fundamental values? Management Science 60: 2324–40. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, Hemang, K. Ramesh, S. Ramu Thiagarajan, and Bala V. Balachandran. 2002. An investigation of the informational role of short interest in the Nasdaq market. The Journal of Finance 57: 2263–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, Douglas W., and Robert E. Verrecchia. 1987. Constraints on short-selling and asset price adjustment to private information. Journal of Financial Economics 18: 277–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffie, Darrell, Nicolae Garleanu, and Lasse Heje Pedersen. 2002. Securities lending, shorting, and pricing. Journal of Financial Economics 66: 307–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelberg, Joseph E., Adam V. Reed, and Matthew C. Ringgenberg. 2012. How are shorts informed? Short sellers, news, and information processing. Journal of Financial Economics 105: 260–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelberg, Joseph E., Adam V. Reed, and Matthew C. Ringgenberg. 2018. Short-selling risk. The Journal of Finance 73: 755–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Vivian W., Allen H. Huang, and Jonathan M. Karpoff. 2016. Short selling and earnings management: A controlled experiment. The Journal of Finance 71: 1251–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, Simon, Charles P. Himmelberg, and Gur Huberman. 2005. Do Stock Price Bubbles Influence Corporate Investment? Journal of Monetary Economics 52: 805–27. [Google Scholar]

- Grullon, Gustavo, Sebastien Michenaud, and James P. Weston. 2015. The Real Effects of Short-Selling Constraints. The Review of Financial Studies 28: 1737–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Jie, Xiao Ren, and Xuan Tian. 2023. Do Short Sellers Affect Corporate Innovation? Evidence from a Policy Experiment. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/rcfs/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/rcfs/cfad007/7087109?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Heath, Davidson, Matthew Ringgenberg, Mehrdad Samadi, and Ingrid M. Werner. 2023. Reusing Natural Experiments. Journal of Finance. forthcoming. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3457525 (accessed on 12 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Henry, Darren. 2004. Corporate governance and ownership structure of target companies and the outcome of takeovers. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 12: 419–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Yen-Sheng, and Ralph A. Walkling. 1987. Target abnormal returns associated with acquisition announcements: Payment, acquisition form, and managerial resistance. Journal of Financial Economics 19: 329–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Byoung-Hyoun, Baixiao Liu, and Wei Xu. 2019. Arbitrage involvement and security prices. Management Science 65: 2858–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, Robert H., and Michael A. Mazzeo. 1991. Stock price movements around acquisition announcements and management’s response. Journal of Business 64: 139–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kau, James B., James S. Linck, and Paul H. Rubin. 2008. Do managers listen to the market? Journal of Corporate Finance 14: 347–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohers, Ninon, and Theodor Kohers. 2000. The value creation potential of high-tech mergers. Financial Analysts Journal 56: 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, Owen A. 2012. Go down fighting: Short sellers vs. firms. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies 2: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvak, Kate, Bernard S. Black, and Woongsun Yoo. 2020. The SEC’s Busted Randomized Experiment: What Can and Cannot Be Learned. Working Paper. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2820031 (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Liu, Baixiao, and John J. McConnell. 2013. The role of the media in corporate governance: Do the media influence managers’ capital allocation decisions? Journal of Financial Economics 110: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungqvist, Alexander, and Wenlan Qian. 2016. How constraining are limits to arbitrage? The Review of Financial Studies 29: 1975–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Yuanzhi. 2005. Do insiders learn from outsiders? Evidence from mergers and acquisitions. The Journal of Finance 60: 1951–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, Massimo, Bohui Zhang, and Hong Zhang. 2015. The invisible hand of short selling: Does short selling discipline earnings management? The Review of Financial Studies 28: 1701–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masulis, Ronald W., Cong Wang, and Fei Xie. 2009. Agency problems at dual-class companies. The Journal of Finance 64: 1697–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Edward M. 1977. Risk, uncertainty, and divergence of opinion. The Journal of Finance 32: 1151–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessin, Allan. 1978. Fundamentals of the Securities Industry. New York: New York Institute of Finance, p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, Joseph P., and Michael Wolf. 2005. Stepwise multiple testing as formalized data snooping. Econometrica 73: 1237–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffi, Pedro A., and Kari Sigurdsson. 2011. Price efficiency and short selling. The Review of Financial Studies 24: 821–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2007. Economic Analysis of the Short Sale Price Restrictions under the Regulation SHO Pilot; Office of Economic Analysis. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/news/studies/2007/regshopilot020607.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Senchack, A. J., Jr., and Laura T. Starks. 1993. Short sale restrictions and market reaction to short-interest announcements. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 28: 177–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkling, Ralph A. 1985. Predicting tender offer success: A logistic analysis. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 20: 461–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Panel A: Distribution of acquisition attempts across years | ||||

| Year | Pilot Acquirers | Nonpilot Acquirers | % Pilot Acquirers | |

| 2002 | 15 | 39 | 27.78% | |

| 2003 | 21 | 49 | 30.00% | |

| 2004 | 46 | 74 | 38.33% | |

| 2005 | 39 | 78 | 33.33% | |

| 2006 | 46 | 65 | 41.44% | |

| 2007 | 33 | 65 | 33.67% | |

| 2008 | 24 | 48 | 33.33% | |

| 2009 | 14 | 25 | 35.90% | |

| 2010 | 31 | 44 | 41.33% | |

| Total | 269 | 487 | 35.58% | |

| Panel B: Distribution of acquisition attempts across industries | ||||

| Industry | N | % of Acquisitions Attempts | Pilot Acquirers | % Pilot Acquirers Acquisitions |

| Energy | 65 | 8.60% | 31 | 32.29% |

| Materials | 23 | 3.04% | 8 | 25.81% |

| Industrials | 73 | 9.66% | 23 | 23.96% |

| Consumer Discretionary | 42 | 5.56% | 16 | 27.59% |

| Consumer Staples | 17 | 2.25% | 8 | 32.00% |

| Health Care | 114 | 15.08% | 38 | 25.00% |

| Financials | 139 | 18.39% | 54 | 27.98% |

| Information Technology | 167 | 22.09% | 54 | 24.43% |

| Telecommunication Services | 28 | 3.70% | 7 | 20.00% |

| Utilities | 19 | 2.51% | 8 | 29.63% |

| Real Estate | 69 | 9.13% | 22 | 24.18% |

| Total | 756 | 100.00% | 269 | 35.58% |

| Full Sample | Pilot Acquirers | Nonpilot Acquirers | Difference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Mean | Median | Mean | Median | Mean | Median | |

| Panel A. Acquirer and acquisition characteristics | ||||||||

| Acquirer Size | 17,477.24 | 3396.49 | 13,173.03 | 3334.04 | 19,854.72 | 3430.69 | −6681.69 ** | −96.65 |

| Equity Market-to-Book Ratio | 2.58 | 2.41 | 3.24 | 2.42 | 2.21 | 2.40 | 1.03 ** | 0.02 |

| Log (Firm Age) | 2.94 | 3.00 | 2.91 | 2.94 | 2.95 | 3.00 | −0.05 | −0.05 |

| Transaction Value | 1785.32 | 289.20 | 2104.46 | 300.00 | 1609.04 | 275.00 | 495.42 | 25.00 |

| CAR (%) | −3.81 | −2.22 | −4.14 | −2.59 | −3.63 | −2.13 | −0.52 | −0.46 * |

| Panel B: Percentage of acquisition attempts with the following characteristics (in %) | ||||||||

| Defense Dummy | 1.06 | - | 1.49 | - | 0.82 | - | 0.67 | - |

| Compete Dummy | 2.51 | - | 4.09 | - | 1.64 | - | 2.45 * | - |

| Hostile Dummy | 0.79 | - | 0.74 | - | 0.82 | - | −0.08 | - |

| Tender Offer Dummy | 3.57 | - | 4.09 | - | 3.29 | - | 0.80 | - |

| Lockup Dummy | 0.53 | - | 0.74 | - | 0.41 | - | 0.33 | - |

| Termination Fee Dummy | 31.08 | - | 31.60 | - | 30.80 | - | 0.80 | - |

| Stock Dummy | 62.43 | - | 65.06 | - | 60.99 | - | 4.07 | - |

| Same State HQ Dummy | 26.46 | - | 30.11 | - | 24.44 | - | 5.68 * | - |

| Definitive Agreement Dummy | 95.37 | - | 94.05 | - | 96.10 | - | −2.05 | - |

| Dependent Variable: Abandonment (1,0) | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| CAR × Pilot × SHO | −2.087 *** | |

| [−2.67] | ||

| CAR × Pilot × Post-SHO | −0.910 | |

| [−0.82] | ||

| CAR | −0.582 *** | −1.645 *** |

| [−2.71] | [−5.53] | |

| Pilot | −0.001 | |

| [−0.05] | ||

| SHO | 0.032 | |

| [1.60] | ||

| Post-SHO | 0.008 | |

| [0.33] | ||

| CAR × Pilot | 0.720 | |

| [0.87] | ||

| CAR × SHO | 1.850 *** | |

| [4.96] | ||

| CAR × Post-SHO | 1.820 *** | |

| [5.00] | ||

| Pilot × SHO | −0.041 | |

| [−1.60] | ||

| Pilot × Post-SHO | 0.006 | |

| [0.13] | ||

| Defense Dummy | 0.353 *** | 0.371 *** |

| [2.76] | [3.25] | |

| Compete Dummy | 0.334 *** | 0.342 *** |

| [4.64] | [4.35] | |

| Hostile Dummy | 0.518 ** | 0.533 ** |

| [2.22] | [2.40] | |

| Tender Offer Dummy | −0.029 | −0.030 |

| [−0.38] | [−0.47] | |

| Lockup Dummy | −0.129 | −0.164 |

| [−0.49] | [−0.68] | |

| Termination Fee Dummy | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| [0.42] | [0.44] | |

| Stock Dummy | 0.010 | 0.009 |

| [0.92] | [0.89] | |

| Ln(Market Cap) | −0.006 | −0.006 |

| [−1.08] | [−1.13] | |

| Same State HQ Dummy | −0.023 *** | −0.030 *** |

| [−3.13] | [−3.72] | |

| Definitive Agreement Dummy | 0.074 *** | 0.070 *** |

| [3.88] | [3.46] | |

| Industry Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 756 | 756 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.2397 | 0.2699 |

| Dependent Variable: Abandonment (1,0) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Diversifying Acquisition | Focused Acquisition | |

| Attempts | Attempts | |

| CAR × Pilot × SHO | −7.524 ** | −0.338 |

| [−2.37] | [−0.37] | |

| CAR × Pilot × Post-SHO | −2.310 | 1.683 |

| [−1.66] | [1.63] | |

| CAR | −1.995 * | −1.668 *** |

| [−1.67] | [−4.30] | |

| Pilot | 0.050 | −0.019 |

| [1.09] | [−0.62] | |

| SHO | −0.035 | 0.030 |

| [−0.31] | [1.24] | |

| Post-SHO | −0.011 | −0.036 |

| [−0.11] | [−1.17] | |

| CAR × Pilot | 2.000 | −1.178 |

| [1.47] | [−1.39] | |

| CAR × SHO | 1.959 | 1.688 *** |

| [1.62] | [4.03] | |

| CAR × Post-SHO | 2.232 * | 1.395 *** |

| [1.79] | [3.34] | |

| Pilot × SHO | −0.150 | −0.005 |

| [−1.50] | [−0.19] | |

| Pilot × Post-SHO | −0.093 | 0.060 |

| [−1.46] | [1.14] | |

| Industry Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 197 | 559 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.1334 | 0.1714 |

| Dependent Variable: Abandonment (1,0) | ||

|---|---|---|

| High-Tech Target | Non-High-Tech Target | |

| CAR × Pilot × SHO | −2.334 *** | −1.255 |

| [−3.22] | [−1.11] | |

| CAR × Pilot × Post-SHO | −1.943 | 0.338 |

| [−1.11] | [0.26] | |

| CAR | −1.126 *** | −1.731 *** |

| [−2.88] | [−3.27] | |

| Pilot | −0.022 | 0.021 |

| [−0.25] | [0.65] | |

| SHO | −0.062 | 0.034 |

| [−0.78] | [1.53] | |

| Post-SHO | −0.115 | 0.000 |

| [−0.88] | [0.01] | |

| CAR × Pilot | 0.725 | 0.006 |

| [0.82] | [0.01] | |

| CAR × SHO | 0.856 | 1.920 *** |

| [1.23] | [3.88] | |

| CAR × Post-SHO | 1.204 *** | 1.866 *** |

| [3.39] | [2.80] | |

| Pilot × SHO | −0.030 | −0.060 ** |

| [−0.40] | [−2.12] | |

| Pilot × Post-SHO | −0.050 | 0.018 |

| [−0.42] | [0.35] | |

| Industry Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 203 | 553 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.1048 | 0.1614 |

| Dependent Variable: Abandonment (1,0) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Strong Shareholder Rights | Weak Shareholder Rights | |

| CAR × Pilot × SHO | −4.387 *** | −1.621 ** |

| [−4.03] | [−2.26] | |

| CAR × Pilot × Post-SHO | −0.935 | −0.207 |

| [−1.55] | [−0.49] | |

| CAR | −2.719 *** | −2.007 *** |

| [−7.74] | [−5.95] | |

| Pilot | 0.068 | 0.065 |

| [1.31] | [1.07] | |

| SHO | −0.060 | 0.012 |

| [−0.48] | [0.22] | |

| Post-SHO | −0.151 | −0.053 |

| [−1.47] | [−1.03] | |

| CAR × Pilot | 2.486 *** | 1.704 *** |

| [6.50] | [3.06] | |

| CAR × SHO | 2.758 *** | 2.167 *** |

| [7.85] | [5.80] | |

| CAR × Post-SHO | 1.917 *** | 2.069 *** |

| [3.93] | [5.16] | |

| Pilot × SHO | −0.115 ** | −0.077 |

| [−2.15] | [−1.13] | |

| Pilot × Post-SHO | 0.000 | −0.056 |

| [0.00] | [−0.88] | |

| Industry Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 246 | 253 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.1883 | 0.1918 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, B.; McConnell, J.J.; Schrowang, A. The Effect of Short-Sale Restrictions on Corporate Managers. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2023, 16, 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16110486

Liu B, McConnell JJ, Schrowang A. The Effect of Short-Sale Restrictions on Corporate Managers. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2023; 16(11):486. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16110486

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Baixiao, John J. McConnell, and Andrew Schrowang. 2023. "The Effect of Short-Sale Restrictions on Corporate Managers" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16, no. 11: 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16110486

APA StyleLiu, B., McConnell, J. J., & Schrowang, A. (2023). The Effect of Short-Sale Restrictions on Corporate Managers. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(11), 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16110486