Effect of Aid-for-Trade Flows on Investment-Oriented Remittance Flows

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Discussion on the Effect of AfT Flows on Investment-Oriented Remittance Flows

2.1. Trade Costs Raise Uncertainty and Could Adversely Affect Households’ Decisions to Invest Part of Their Remittances on Business Activities

2.2. AfT Interventions for the Development of Productive Capacities Can Stimulate Investment-Oriented Remittance Inflows

2.3. AfT Interventions for Economic Infrastructure and the Interventions in Favor of Trade Policy and Regulation Can Boost Households’ Remittance-Related Investments on Business Activities through Its Effect on Trade Costs

2.4. Other Possible Effects of Development Aid, including AfT and Non-AfT Flows on Investment-Oriented Remittance Inflows

3. Empirical Strategy

3.1. Model Specification

3.1.1. Effect of Noninvestment-Oriented Remittances

3.1.2. Effect of GDP per Capita on Investment-Oriented Remittances

3.1.3. Effect of Non-AfT Flows

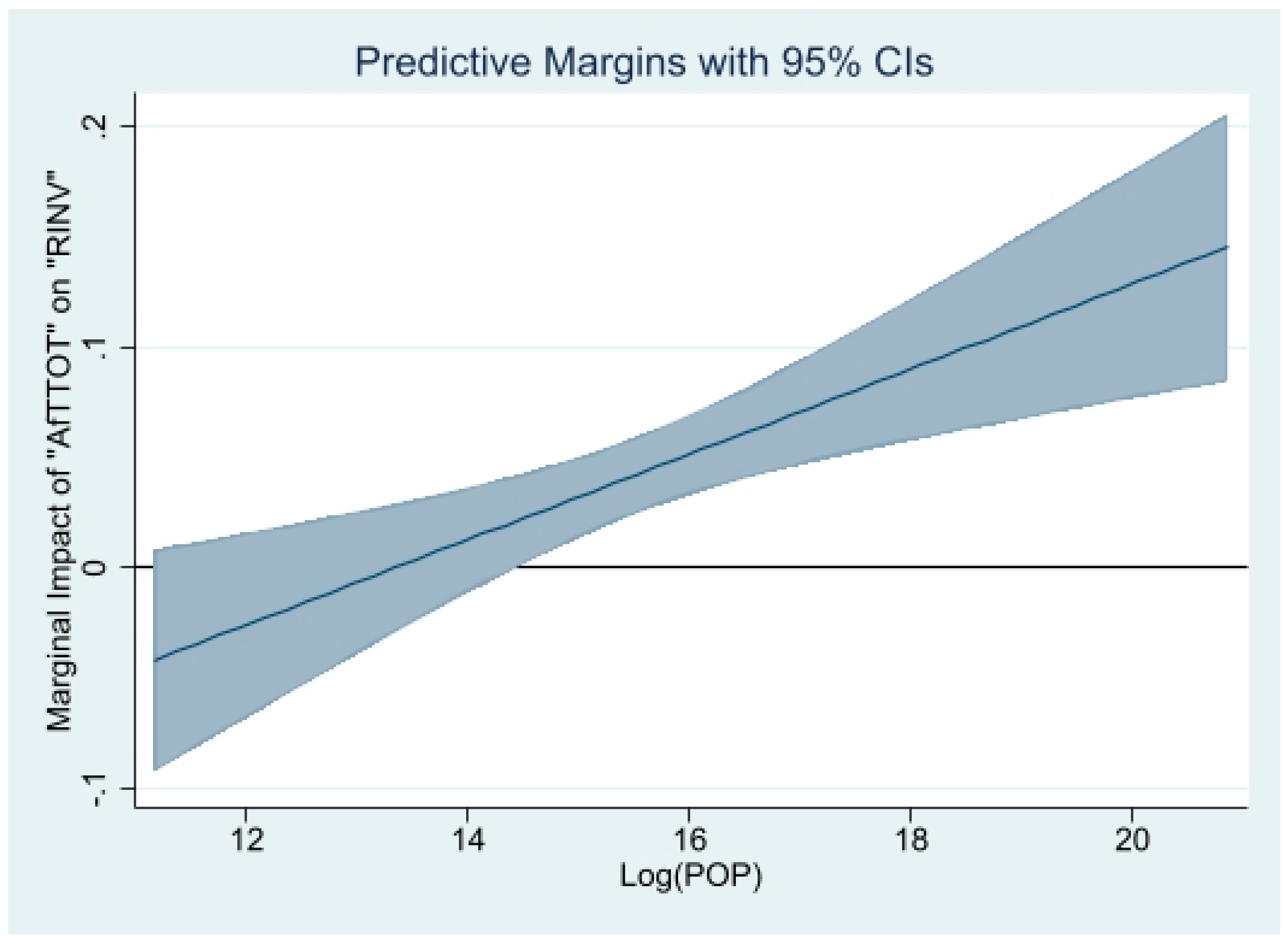

3.1.4. Effect of the Population Size

3.1.5. Effect of Financial Development

3.1.6. Effect of the Real Exchange Rate and Terms of Trade

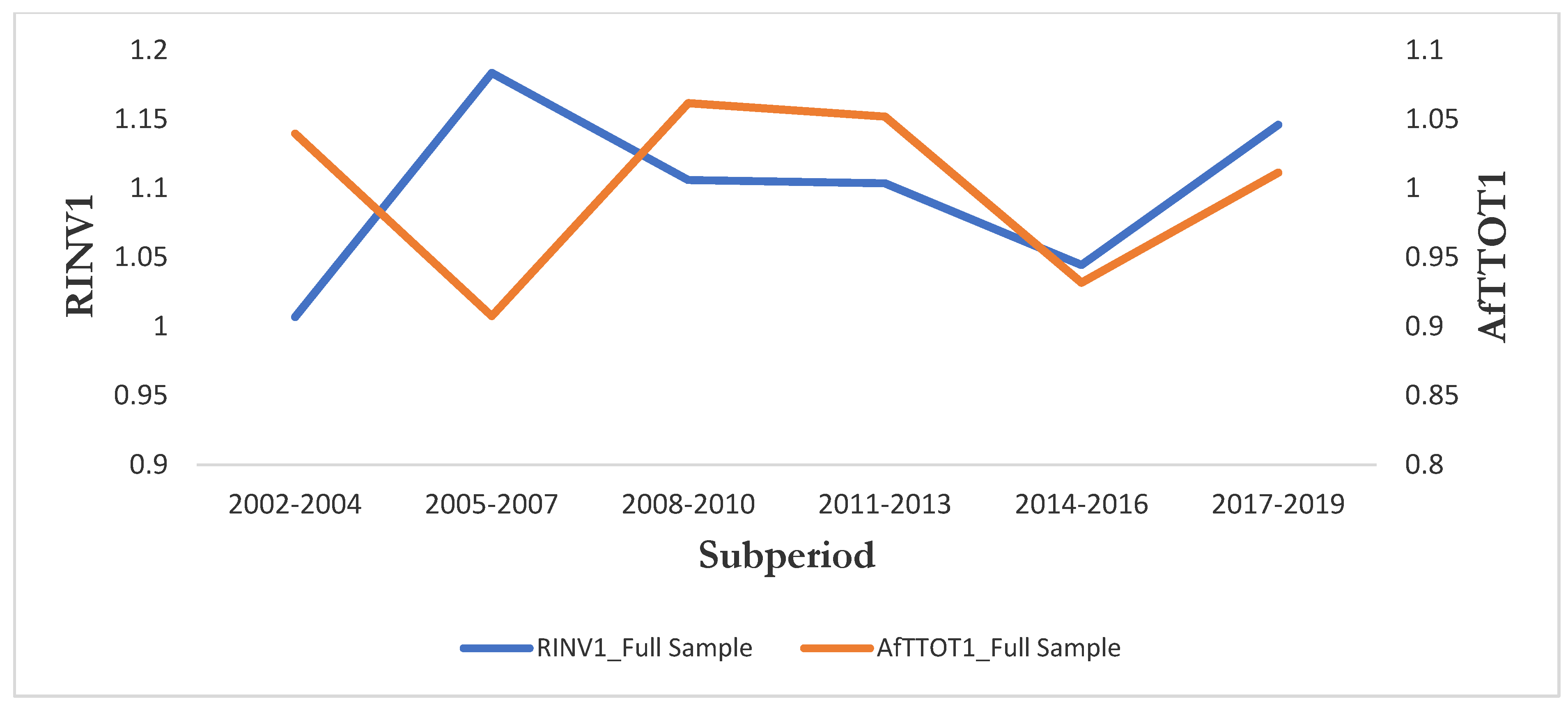

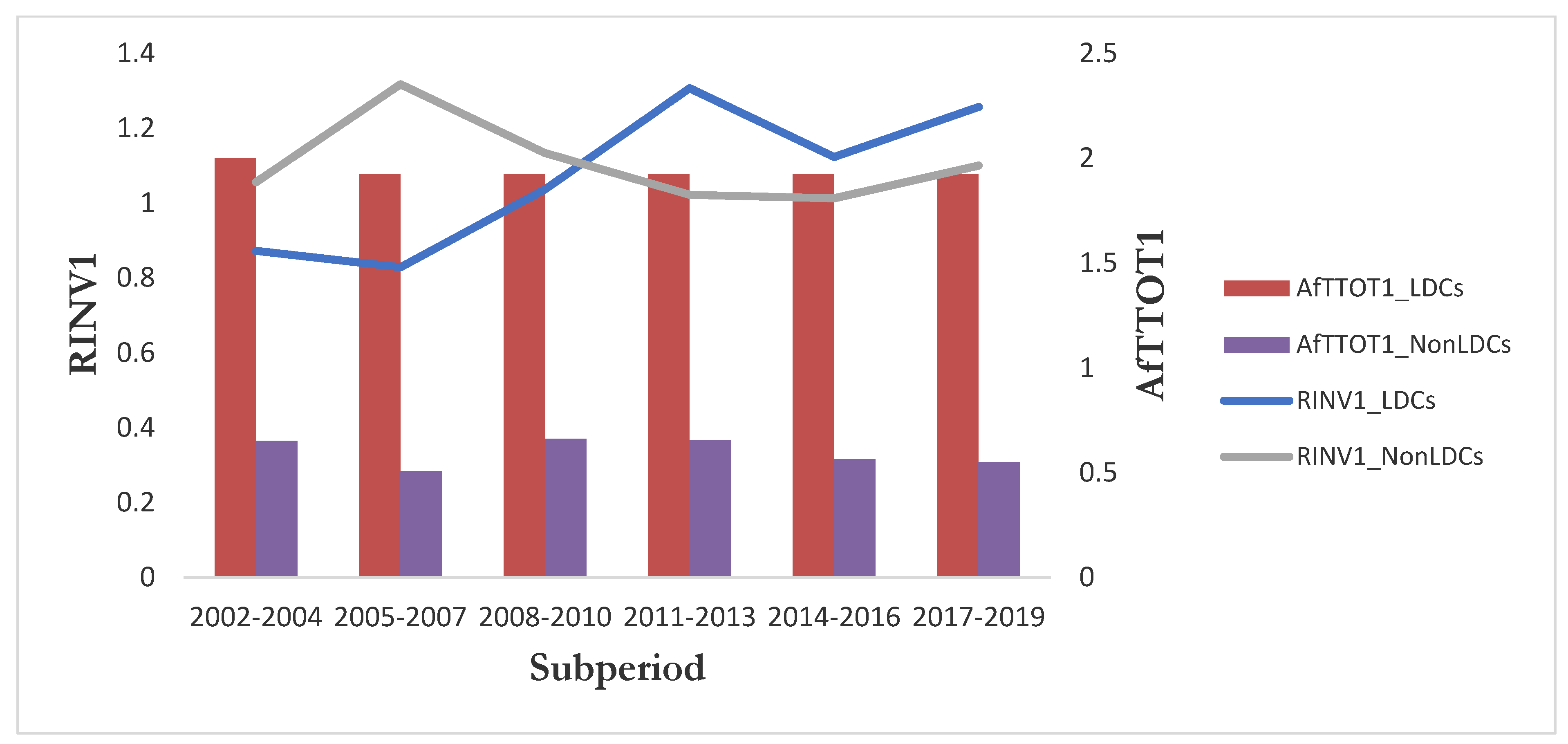

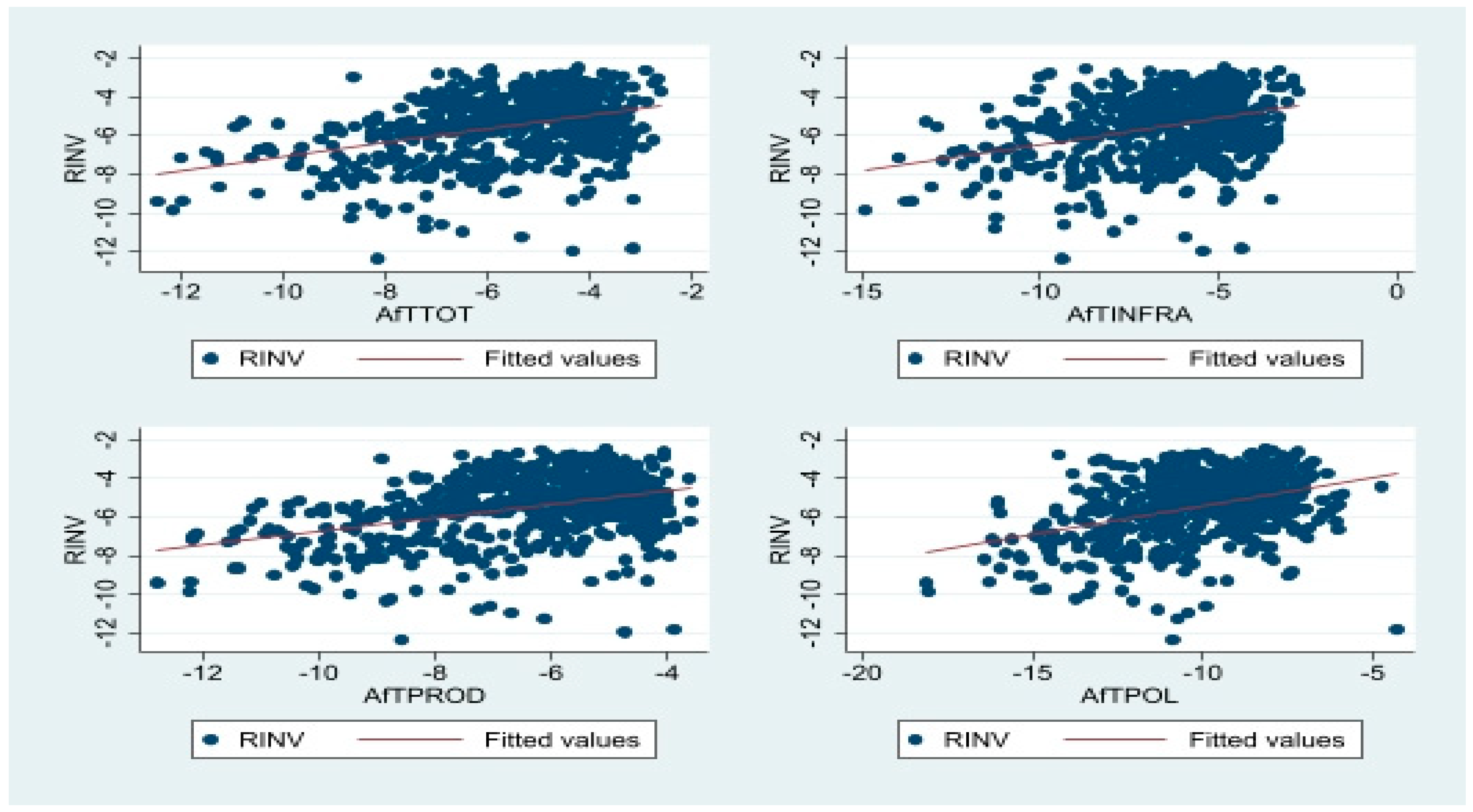

3.2. Preliminary Data Analysis

3.3. Econometric Approach

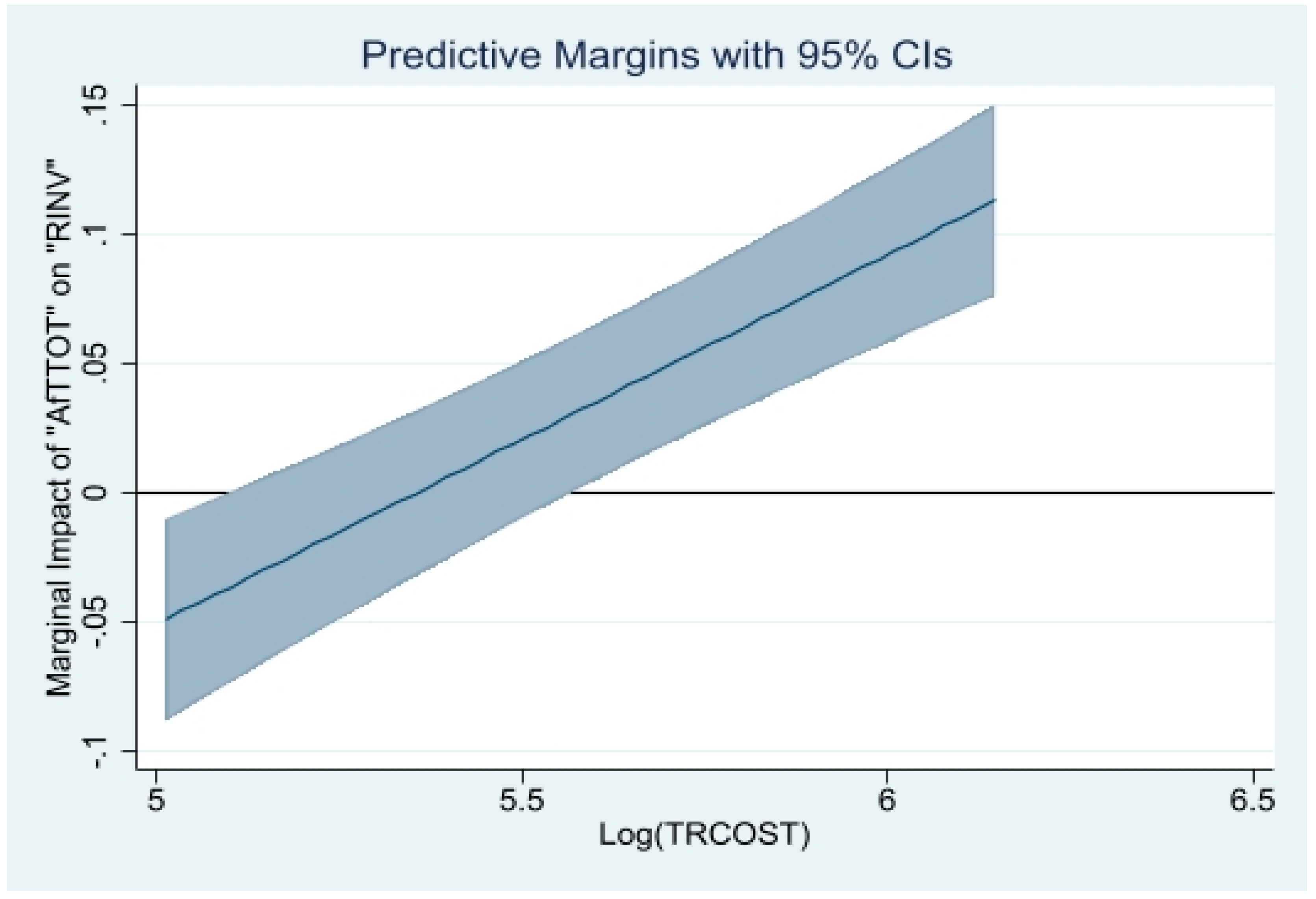

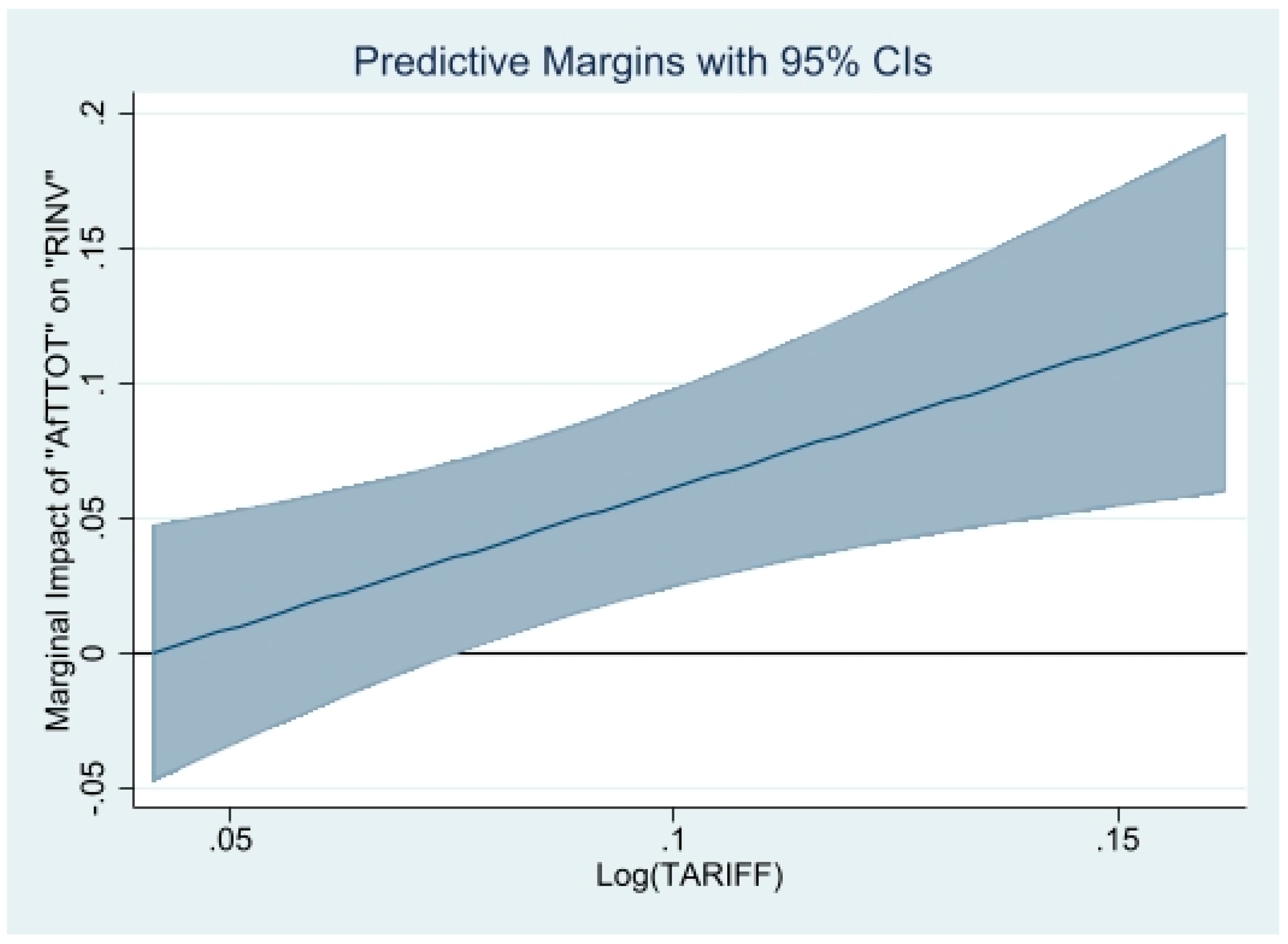

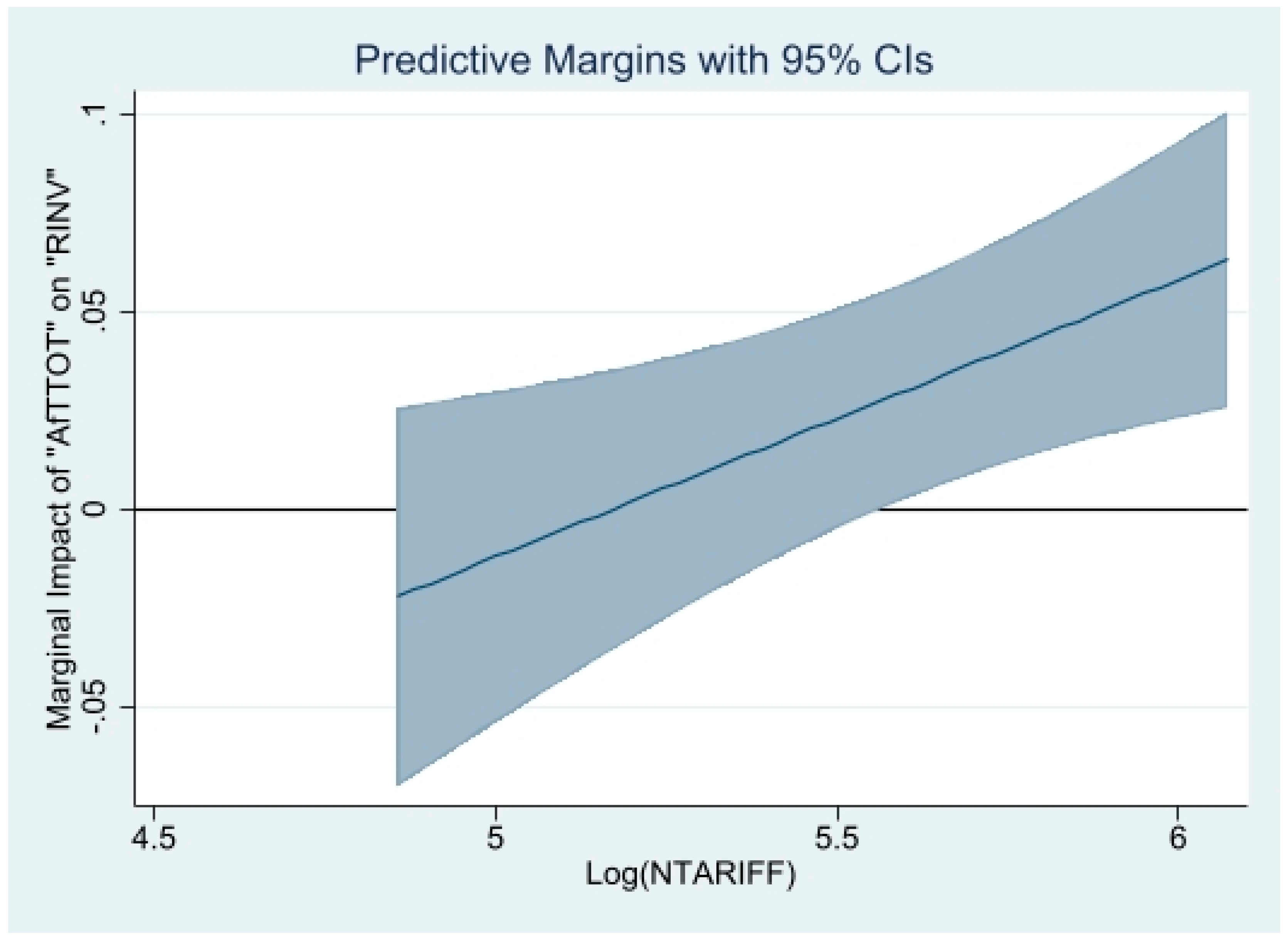

4. Empirical Outcomes

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| RINV | This is the share of remittance-oriented investment in GDP. It is not expressed in percentage. It has been computed as the share of total remittances received by a given country (in a given year) in GDP multiplied by the annual investment rate (investment as a share of GDP, not expressed in percentage). | Author’s calculation based on data on the share of total remittances received in GDP collected from the from the World Development Indicators (WDI) and data on annual investment rate (investment as a share of GDP) drawn from the Penn World Table (version 10.0). |

| RNINV | This is the difference between the share of total remittances received in GDP and the share of remittance-oriented investment in GDP. | Author’s calculation based on data on the investment-oriented remittances computed above. |

| AfTTOT, AfTINFRA, AfTPROD, AfTPOL | “AfTTOT” is the total real gross disbursements of total aid for trade. “AfTINFRA” is the real gross disbursements of aid for trade allocated to the buildup of economic infrastructure. “AfTPROD” is the real gross disbursements of aid for trade for building productive capacities. “AfTPOL” is the real gross disbursements of Aid allocated for trade policies and regulation. All four AfT variables are expressed as a share of GDP (not in percentage). | Author’s calculation based on data extracted from the OECD statistical database on development, in particular the OECD/DAC-CRS (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development/Donor Assistance Committee)-Credit Reporting System (CRS). Aid-for-trade data cover the following three main categories (the CRS codes are in brackets): aid for trade for economic infrastructure (“AfTINFRA”), which includes transport and storage (210), communications (220) and energy generation and supply (230); aid for trade for building productive capacity (“AfTPROD”), which includes banking and financial services (240), business and other services (250), agriculture (311), forestry (312), fishing (313), industry (321), mineral resources and mining (322), and tourism (332); and aid-for-trade policy and regulations (“AfTPOL”), which includes trade policy and regulations and trade-related adjustment (331). |

| TRCOST | This is the indicator of the average comprehensive (overall) trade costs. We have calculated the average overall trade costs for a given country in a given year as the average of the bilateral overall trade costs on goods across all trading partners of this country. Data on bilateral overall trade costs have been computed by Arvis et al. (2012, 2016) by following the approach proposed by Novy (2013). Arvis et al. (2012, 2016) have built on the the definition of trade costs by Anderson and van Wincoop (2004) and considered bilateral comprehensive trade costs as all costs involved in trading goods (agricultural and manufactured goods) internationally with another partner (i.e., bilaterally) relative to those involved in trading goods domestically (i.e., intranationally). Hence, the bilateral comprehensive trade cost indicator captures trade costs in its wider sense, including not only international transport costs and tariffs but also other trade cost components discussed in Anderson and van Wincoop (2004), such as direct and indirect costs associated with differences in languages, currencies and cumbersome import or export procedures. Higher values of the indicator of average overall trade costs indicate higher overall trade costs. Detailed information on the methodology used to compute the bilateral comprehensive trade costs can be found in Arvis et al. (2012, 2016), as well as in the short explanatory note accessible online at https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/Trade%20Cost%20Database%20-%20User%20note.pdf. (accessed on 1 January 2022). | Author’s computation using the ESCAP-World Bank Trade Cost Database. Accessible online at https://www.unescap.org/resources/escap-world-bank-trade-cost-database. (accessed on 1 January 2022). |

| TARIFF | This is the indicator of the average tariff costs. It is the tariff component of the average overall trade costs. We have computed it, for a given country in a given year, as the average of the bilateral comprehensive tariff costs across all trading partners of this country. Data on the bilateral tariff cost indicator have been computed by Arvis et al. (2012, 2016). As the bilateral tariff cost indicator is (like the comprehensive trade costs) bidirectional in nature (i.e., include trade costs to and from a pair of countries), Arvis et al. (2012, 2016) have measured it as the geometric average of the tariffs imposed by the two partner countries on each other’s imports (of agricultural and manufactured goods). Higher values of the indicator of the average tariff costs show an increase in the average tariff costs. Detailed information on the methodology used to compute the bilateral tariff costs can be found in Arvis et al. (2012, 2016), as well as in the short explanatory note accessible online at https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/Trade%20Cost%20Database%20-%20User%20note.pdf. (accessed on 1 January 2022). | Author’s computation using the ESCAP-World Bank Trade Cost Database. Accessible online at https://www.unescap.org/resources/escap-world-bank-trade-cost-database. (accessed on 1 January 2022). |

| NTARIFF | This is the indicator of the average nontariff costs. It represents the second component (i.e., nontariff component) of the comprehensive trade costs. This is the indicator of the comprehensive trade costs, excluding the tariff costs. We have computed it, for a given country in a given year, as the average of the bilateral comprehensive nontariff costs (i.e., the comprehensive trade costs, excluding the tariff costs) across all trading partners of this country. Data on the bilateral nontariff cost indicator have been computed by Arvis et al. (2012, 2016) by following Anderson and van Wincoop (2004). Comprehensive trade costs, excluding tariffs, encompass all additional costs other than tariff costs involved in trading goods (agricultural and manufactured goods) bilaterally rather than domestically. Higher values of the indicator of average nontariff costs reflect a rise in nontariff costs. Detailed information on the methodology used to compute the bilateral tariff costs can be found in Arvis et al. (2012, 2016), as well as in the short explanatory note accessible online at https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/Trade%20Cost%20Database%20-%20User%20note.pdf. (accessed on 1 January 2022). | Author’s computation using the ESCAP-World Bank Trade Cost Database. Accessible online at https://www.unescap.org/resources/escap-world-bank-trade-cost-database. (accessed on 1 January 2022). |

| Non-AfTTOT | This is the measure of the development aid allocated to other sectors in the economy than the trade sector. It has been computed as the difference between the gross disbursements of total ODA and the gross disbursements of total aid for trade (both being expressed in constant prices 2019, USD). | Author’s calculation based on data extracted from the OECD/DAC-CRS database. |

| GDPC | Real per capita gross domestic product (constant 2015 USD). | United States Department of Agriculture (UNDA)’s Economic Research Service. See online at https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/international-macroeconomic-data-set/international-macroeconomic-data-set/. (accessed on 1 January 2022). |

| REER | This is the measure of the real effective exchange rate (CPI-based) (REER), computed using a nominal effective exchange rate based on 66 trading partners. An increase in the index indicates an appreciation in the real effective exchange rate, i.e., an appreciation in the home currency against the basket of currencies of trading partners. | Bruegel data sets (see Darvas 2012a, 2012b). The data set can be found online at: http://bruegel.org/publications/datasets/real-effective-exchange-rates-for-178-countries-a-new-database/. (accessed on 1 January 2022). |

| TERMS | This is the indicator of terms of trade, measured by the net barter terms of trade index (2000 = 100). This indicator is not expressed in percentage. | Author’s calculation based on terms of trade data extracted from the WDI. |

| FINDEV | This is a proxy for financial development and is measured by the share of domestic credit to the private sector by banks, in GDP (not expressed in percentage). | WDI |

| POP | Total population | WDI |

| INST | This is the variable capturing institutional quality. It has been computed by extracting the first principal component (based on factor analysis) of the following six indicators of governance. These indicators are political stability and the absence of violence/terrorism; regulatory quality; the rule of law; government effectiveness; voice and accountability; and corruption. Higher values of the index “INST” are associated with better governance and institutional quality, while lower values reflect worse governance and institutional quality. | Data on the components of “INST” variables have been extracted from World Bank Governance Indicators developed by Kaufmann et al. (2010) and updated recently. See online at https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/. (accessed on 1 January 2022) |

Appendix B

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RINV | 505 | 0.011 | 0.014 | 0.0000043 | 0.086 |

| RNONINV | 505 | 0.046 | 0.058 | 0.000018 | 0.388 |

| AfTTOT | 505 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.0000039 | 0.074 |

| AfTINFRA | 505 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.00000033 | 0.062 |

| AfTPROD | 505 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.0000028 | 0.027 |

| AfTPOL | 495 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000000014 | 0.014 |

| TRCOST | 470 | 319.536 | 56.167 | 150.2395 | 467.268 |

| TARIFF | 475 | 1.096 | 0.022 | 1.042 | 1.176 |

| NTARIFF | 455 | 279.107 | 52.329 | 128.532 | 433.378 |

| Non-AfTTOT | 505 | 0.037 | 0.059 | 0.00008 | 0.675 |

| FINDEV | 505 | 0.383 | 0.298 | 0.0213 | 1.594 |

| TERMS | 505 | 1.240 | 0.449 | 0.48395 | 4.537 |

| GDPC | 505 | 4247.006 | 3791.610 | 280.6682 | 18,663.550 |

| POP | 505 | 53,200,000 | 184,000,000 | 70,698.33 | 1,390,000,000 |

Appendix C

| Full Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | Dominican Republic | Liberia ** | Sudan ** |

| Algeria | Ecuador | Madagascar ** | Suriname |

| Angola ** | Egypt, Arab Rep. | Malaysia | Syrian Arab Republic |

| Antigua and Barbuda | El Salvador | Maldives | Tajikistan |

| Argentina | Eswatini | Mali ** | Tanzania ** |

| Armenia | Ethiopia ** | Mauritius | Thailand |

| Azerbaijan | Fiji | Mexico | Togo ** |

| Bangladesh ** | Gabon | Moldova | Tunisia |

| Belarus | Gambia ** | Mongolia | Turkey |

| Belize | Georgia | Morocco | Uganda ** |

| Benin ** | Ghana | Mozambique ** | Ukraine |

| Bhutan ** | Grenada | Namibia | Uruguay |

| Bolivia | Guatemala | Nepal ** | Uzbekistan |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Guinea ** | Nicaragua | Venezuela, RB |

| Botswana | Guinea-Bissau ** | Niger ** | Vietnam |

| Brazil | Guyana | Nigeria | Zambia ** |

| Burkina Faso ** | Haiti ** | North Macedonia | |

| Burundi ** | Honduras | Pakistan | |

| Cabo Verde | India | Panama | |

| Cambodia ** | Indonesia | Paraguay | |

| Cameroon | Iran, Islamic Rep. | Peru | |

| Chile | Iraq | Philippines | |

| China | Jamaica | Rwanda ** | |

| Colombia | Jordan | Senegal ** | |

| Congo, Dem. Rep ** | Kazakhstan | Serbia | |

| Congo, Rep. | Kenya | Seychelles | |

| Costa Rica | Kyrgyz Republic | Sierra Leone ** | |

| Côte d’Ivoire | Lao PDR ** | South Africa | |

| Djibouti ** | Lebanon | Sri Lanka | |

| Dominica | Lesotho ** | St. Vincent and the Grenadines | |

| 1 | The category of LDCs includes countries that are considered by the United Nations as the poorest and most vulnerable countries (in the world) both to exogenous economic and financial shocks and to environmental shocks. Further information on this group of countries can be obtained online at https://www.un.org/ohrlls/content/least-developed-countries (Access to the link on 1 March 2022). |

| 2 | Benziane et al. (2022) have provided a recent literature review on the effects of AfT flows in recipient countries. |

| 3 | See, for example, Amuedo-Dorantes and Pozo (2006); Buckley and Hofmann (2012); Haas (2005); Le (2011); Le and Bodman (2011); Mohapatra et al. (2011); Martinez et al. (2015); Saadi (2020); Shapiro and Mandelman (2016); Vaaler (2011, 2013); Woodruff and Zenteno (2007); Yang (2008, 2011); and Zheng and Musteen (2018). |

| 4 | This is one of the scarce studies that have investigated the effect of remittances on aid dependency rather than the effect of aid on remittances (Kpodar and Le Goff 2012). |

| 5 | According to Portugal-Perez and Wilson (2012, p. 1296), hard infrastructure encompasses highways, railroads, ports, etc., while soft infrastructure entails transparency, customs efficiency and institutional reforms. |

| 6 | Calì and te Velde (2011) have recognized the arbitrary choice of the lag with which AfT flows could affect exports in recipient countries. For this reason, they have used two lags (one-period lag and two-period lag) for the AfT variables in their analysis. In the present study, we present the estimates associated with only one lag of the share of the total AfT flows in GDP. The outcomes with a two-period lag of this variable are qualitatively similar to the ones with a one-period lag of the AfT variable and can be obtained upon request. |

| 7 | The likely state-dependence nature of the dependent variable that would require the estimation of dynamic model (1) would yield biased estimates if the estimation were performed using the fixed-effects estimator. This is because the lagged dependent variable will be correlated with the fixed effects in the error term, and the bias of this correlation would increase because the time dimension of the panel data set is small (this is the so-called Nickel bias—Nickell 1981). |

| 8 | Chami et al. (2008) have considered that remittance-dependent countries are those whose ratio of remittances to GDP is equal to or higher than 5%. The present analysis focuses on the countries’ dependence on investment-oriented remittance inflows. |

| 9 | As well noted by Hou et al. (2021), the methodology adopted by Arvis et al. (2012, 2016) for computing trade cost parameters is theoretically well grounded in the gravity model (Anderson and van Wincoop 2004), the Ricardian model (Eaton and Kortum 2002) and the heterogeneous firms model (Melitz and Ottaviano 2008). |

| 10 | This result concerns the estimate obtained from the FEs estimator, as for the result in column (1), the estimate is not significant at the conventional significance levels. |

| 11 | We obtained outcomes that are qualitatively similar to these ones when we examined whether the effect of each of the components of the total AfT flows on investment-oriented remittance flows depends on the population size. In other words, the effects of each of these components of total AfT flows are positive and increase with the population size. The results on these estimates can be obtained upon request. |

| 12 | The other expected option was for the introduction of the trade cost indicator to cancel out the significance of the coefficient of the variable capturing the total AfT flows, at the 10% level. |

References

- Abbas, Syed Ali, Eliyathamby A. Selvanathan, Saroja S. Selvanathan, and Jayatilleke S. Bandaralage. 2021. Are remittances and foreign aid interlinked? Evidence from least developed and developing countries. Economic Modelling 94: 265–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiad, Abdul, Davide Furceri, and Petia Topalova. 2016. The macroeconomic effects of public investment: Evidence from advanced economies. Journal of Macroeconomics 50: 224–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, Pablo, and Andrés Loza. 2005. Short and Long Run Determinants of Private Investment in Argentina. Journal of Applied Economics 8: 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, Pablo A., Emmanuel K. K. Lartey, and Federico S. Mandelman. 2009. Remittances and the Dutch disease. Journal of International Economics 79: 102–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Richard H., Jr. 2011. Evaluating the economic impact of international remittances on developing countries using household surveys: A literature review. Journal of Development Studies 47: 809–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenutsi, Deodat E., and Christian R. K. Ahortor. 2021. Macroeconomic Determinants of Remittance Flows to Sub-Saharan Africa. AERC Research Paper 415. Nairobi: African Economic Research Consortium. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, José Antonio, Carlos Garcimartin, and Virmantas Kvedaras. 2020. Determinants of institutional quality: An empirical exploration. Journal of Economic Policy Reform 23: 229–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Borrego, César, and Manuel Arellano. 1999. Symmetrically normalized instrumental-variable estimation using panel data. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 17: 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina, and Susan Pozo. 2004. Workers’ Remittances and the Real Exchange Rate: A Paradox of Gifts. World Development 32: 1407–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina, and Susan Pozo. 2006. Remittance receipt and business ownership in the Dominican Republic. World Economy 29: 939–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, James E., and Douglas Marcouiller. 2002. Insecurity and the pattern of trade: An empirical investigation. Review of Economics and Statistics 84: 342–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, James E., and Eric van Wincoop. 2004. Trade Costs. Journal of Economic Literature 42: 691–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, Sajid, and Lan Phi Nguyen. 2011. Foreign direct investment and export spillovers: Evidence from Vietnam. International Business Review 20: 177–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, Sebastian, David Audretsch, and David Urbano. 2021. Why is export-oriented entrepreneurship more prevalent in some countries than others? Contextual antecedents and economic consequences. Journal of World Business 56: 101177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, Manuel, and Olympia Bover. 1995. Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error components models. Journal of Econometrics 68: 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, Manuel, and Stephen Bond. 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies 58: 277–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvis, Jean-François, Yann Duval, Ben Shepherd, and Chorthip Utoktham. 2012. Trade Costs in the Developing World: 1995–2010. ARTNeT Working Papers, No. 121/December 2012 (AWP No. 121). Bangkok: Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade, ESCAP. [Google Scholar]

- Arvis, Jean-François, Yann Duval, Ben Shepherd, Chorthip Utoktham, and Anasuva Raj. 2016. Trade Costs in the Developing World: 1996–2010. World Trade Review 15: 451–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atems, Bebonchu, and Grayden Shand. 2018. An empirical analysis of the relationship between entrepreneurship and income inequality. Small Business Economics 51: 905–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, David B., Maksim Belitski, Rosa Caiazza, and Sameeksha Desai. 2022. The role of institutions in latent and emergent entrepreneurship. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 174: 121263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadir, Berrak, Santanu Chatterjee, and Thomas Lebesmuehlbacher. 2018. The macroeconomic consequences of remittances. Journal of International Economics 111: 214–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahal, Girish, Mehdi Raissi, and Volodymyr Tulin. 2018. Crowding-out or crowding-in? Public and private investment in India. World Development 109: 323–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, Diogo, Vitor M. Carvalho, and Paulo J. Pereira. 2016. Public stimulus for private investment: An extended real options model. Economic Modelling 52: 742–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, Maria, and Vanessa Strauss-Kahn. 2015. Input-trade liberalization, export prices and quality upgrading. Journal of International Economics 95: 250–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, William J., and Robert J. Strom. 2007. Entrepreneurship and economic growth. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1: 233–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayangos, Veronica, and Karel Jansen. 2011. Remittances and Competitiveness: The Case of the Philippines. World Development 39: 1834–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benziane, Yakoub, Siong Hook Law, Anitha Rosland, and Muhammad Daaniyall Abd Rahman. 2022. Aid for trade initiative 16 years on: Lessons learnt from the empirical literature and recommendations for future directions. Journal of International Trade Law and Policy 21: 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchler, Kassandra, and Katharina Michaelowa. 2016. Making aid work for education in developing countries: An analysis of aid effectiveness for primary education coverage and quality. International Journal of Educational Development 48: 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, and Stephen Bond. 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87: 115–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, Stephen. 2002. Dynamic panel data models: A guide to micro data methods and practice. Portuguese Economic Journal 1: 141–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, Stephen, Anke Hoeffler, and Jonathan Temple. 2001. GMM Estimation of Empirical Growth Models. CEPR Paper DP3048. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi, Maria Elena, Roberto Golinelli, and Giuseppe Parigi. 2010. Why demand uncertainty curbs investment: Evidence from a panel of Italian manufacturing firms. Journal of Macroeconomics 32: 218–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreaux, Christopher John, Anand Jha, and Monica Escaleras. 2021. Weathering the Storm: How Foreign Aid and Institutions Affect Entrepreneurship Following Natural Disasters. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 46: 1843–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougheas, Spiros, Panicos O. Demetriades, and Edgar L. W. Morgenroth. 1999. Infrastructure, Transport Costs and Trade. Journal of International Economics 47: 169–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, Jean-François, Céline Carrère, Patrick Guillaumont, and Jaime de Melo. 2005. Has Distance Died? Evidence from a Panel Gravity Model. World Bank Economic Review 19: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, Aymo, and Beatrice Weder. 1998. Investment and institutional uncertainty: A comparative study of different uncertainty measures. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 134: 513–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, Cynthia, and Erin Trouth Hofmann. 2012. Are remittances an effective mechanism for development? Evidence from Tajikistan, 1999–2007. The Journal of Development Studies 48: 1121–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, Matthias, Ruth Hoekstra, and Jens Königer. 2012. The impact of aid for trade facilitation on the costs of trading. Kyklos 65: 143–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calì, Massimiliano, and Dirk Willem te Velde. 2011. Does Aid for Trade Really Improve Trade Performance? World Development 39: 725–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, Dustin, and Jonathan Munemo. 2019. Regulations, institutional quality, and entrepreneurship. Journal of Regulatory Economics 55: 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chami, Ralph, Adolfo Barajas, Thomas Cosimano, Connel Fullenkamp, Michael Gapen, and Peter Montiel. 2008. Macroeconomic Consequences of Remittances. IMF Occasional Paper no. 259. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Zhiming, and Russell Smyth. 2021. Education and migrant entrepreneurship in urban China. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 188: 506–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Xiaoyong, and Liutang Gong. 2008. Foreign aid, domestic capital accumulation, and foreign borrowing. Journal of Macroeconomics 30: 1269–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvas, Zsolt. 2012a. Compositional Effects on Productivity, Labour Cost and Export Adjustment. Policy Contribution 2012/11. Brussels: Bruegel. [Google Scholar]

- Darvas, Zsolt. 2012b. Real Effective Exchange Rates for 178 Countries: A New Database. Working Paper 2012/06. Brussels: Bruegel. [Google Scholar]

- de Melo, Jaime, and Laurent Wagner. 2016. Aid for Trade and the Trade Facilitation Agreement: What They Can Do for LDCs. Journal of World Trade 50: 935–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, Alan V. 2014. Local comparative advantage: Trade costs and the pattern of trade. International Journal of Economic Theory 10: 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defever, Fabrice, Michele Imbruno, and Richard Kneller. 2020. Trade liberalization, input intermediaries and firm productivity: Evidence from China. Journal of International Economics 126: 103329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakantoni, Antonia, Hubert Escaith, Michael Roberts, and Thomas Verbeet. 2017. Accumulating Trade Costs and Competitiveness in Global Value Chains. WTO Working Paper ERSD-2017-02. Geneva: World Trade Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, Avinash K., and Robert S. Pindyck. 1994. Investment under Uncertainty number 5474. In Economics Books. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donaubauer, Julian, Birgit Meyer, and Peter Nunnenkamp. 2016. Aid, Infrastructure and FDI: Assessing the Transmission Channel with a New Index of Infrastructure. World Development 78: 230–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreger, Christian, and Hans-Eggert Reimers. 2016. Does public investment stimulate private investment? Evidence for the euro area. Economic Modelling 58: 154–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, John C., and Aart C. Kraay. 1998. Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimation with Spatially Dependent Panel Data. Review of Economics and Statistics 80: 549–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Nabamita, and Daniel Meierrieks. 2021. Financial development and entrepreneurship. International Review of Economics & Finance 73: 114–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, Nabamita, and Russell S. Sobel. 2018. Entrepreneurship and human capital: The role of financial development. International Review of Economics & Finance 57: 319–32. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, Jonathan, and Samuel Kortum. 2002. Technology, geography, and trade. Econometrica 70: 1741–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeke, Christian, and Jesse Siminitz. 2018. Trade Uncertainty and Investment in the Euro Area. IMF Working Papers 2018/281. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. 2014. The Impacts of Remittances on Developing Countries. European Parliament, Directorate-General for External Policies of the Union, Karine Lubambu, Publications Office, EXPO/B/DEVE/2013/34. Brussels: European Parliament. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2861/57140 (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Farla, Kristine, Denis de Crombrugghe, and Bart Verspagen. 2016. Institutions, Foreign Direct Investment, and Domestic Investment: Crowding Out or Crowding In? World Development 88: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, Lisandra, and Florian Unger. 2022. Quality and gravity in international trade. Journal of International Economics 137: 103578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, Caroline, and Nikola Spatafora. 2008. Remittances, transaction costs, and informality. Journal of Development Economics 86: 356–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, Michael, and Pamela Mueller. 2008. The effect of new business formation on regional development over time: The case of Germany. Small Business Economics 30: 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghura, Dhaneshwar, and Barry Goodwin. 2000. Determinants of private investment: A cross-regional empirical investigation. Applied Economics 32: 1819–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, Sourafel, Richard Kneller, and Mauro Pisu. 2005. Exports versus FDI: An Empirical Test. Review of World Economics 141: 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2018. Aid for trade and trade policy in recipient countries. The International Trade Journal 32: 439–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2019. Effect of Export Upgrading on Financial Development. Journal of International Commerce, Economics and Policy 10: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2020a. Aid for Trade flows and Real Exchange Rate Volatility in Recipient-Countries. Journal of International Commerce, Economics and Policy 11: 2250001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2020b. Development Aid and Regulatory Policies in Recipient-Countries: Is there a Specific Effect of Aid for Trade? Economics Bulletin 40: 316–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2022. Aid for Trade, export product diversification, and foreign direct investment. Review of Development Economics 26: 534–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goya, Daniel. 2020. The exchange rate and export variety: A cross-country analysis with long panel estimators. International Review of Economics & Finance 70: 649–65. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, Jeremy, and Bruce D. Smith. 1997. Financial markets in development, and the development of financial markets. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 21: 145–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, Gene M., and Elhanan Helpman. 2015. Globalization and growth. American Economic Review 105: 100–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Sanjeev, Catherine A. Pattillo, and Smita Wagh. 2009. Effect of Remittances on Poverty and Financial Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 37: 104–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, Hein. 2005. International migration, remittances, and development: Myths and facts. Third World Quarterly 26: 1269–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, Kyle, and Nuno Limão. 2015. Trade and Investment under Policy Uncertainty: Theory and Firm Evidence. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7: 189–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, Kyle, and Nuno Limão. 2022. Trade Policy Uncertainty. NBER Working Paper 29672. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Helble, Matthias Catherine, Catherine L. Mann, and John S. Wilson. 2012. Aid-for-trade facilitation. Review of World Economics 148: 357–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzer, Dierk, and Michael Grimm. 2012. Does foreign aid increase private investment? Evidence from panel cointegration. Applied Economics 44: 2537–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekman, Bernard, and Alessandro Nicita. 2011. Trade policy, trade costs, and developing country trade. World Development 39: 2069–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Yulin, Yun Wang, and Wenjun Xue. 2021. What explains trade costs? Institutional quality and other determinants. Review of Development Economics 25: 478–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Cui, David Parsley, and Yong Tan. 2021. Exchange rate induced export quality upgrading: A firm-level perspective. Economic Modelling 98: 336–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2015. Private Investment: What’s the Holdup? In IMF World Economic Outlook, Uneven Growth Short and Long-Term Factors. World Economic Outlook, April, chap. 4. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Shaomeng. 2018. Foreign aid: Boosting or hindering entrepreneurship? Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy 7: 248–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongwanich, Juthathip, and Archanun Kohpaiboon. 2008. Private Investment: Trends and Determinants in Thailand. World Development 36: 1709–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, Dale, and Calvin Siebert. 1968. A Comparison of Alternative Theories of Corporate Investment Behavior. American Economic Review 58: 681–712. [Google Scholar]

- Kakhkharova, Jakhongir, Alexandr Akimovb, and Nicholas Rohde. 2017. Transaction costs and recorded remittances in the post-Soviet economies: Evidence from a new dataset on bilateral flows. Economic Modeling 60: 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2010. The Worldwide Governance Indicators Methodology and Analytical Issues. World Bank Policy Research N° 5430 (WPS5430). Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Dongmin, Bohui Zhang, and Jian Zhang. 2022. Higher education and corporate innovation. Journal of Corporate Finance 72: 102165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, Deliana, Rachel Nugent, and Patricia Richter. 2021. Noncommunicable disease outcomes and the effects of vertical and horizontal health aid. Economics & Human Biology 41: 100935. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsadam, Andreas, Gudrun Østby, Siri Aas Rustad, Andreas Forø Tollefsen, and Henrik Urdal. 2018. Development aid and infant mortality: Micro-level evidence from Nigeria. World Development 105: 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kpodar, Kangni, and Maelan Le Goff. 2012. Do Remittances Reduce Aid Dependency? FERDI Working Paper 34. Clermont-Ferrand: Fondation pour les Études et Recherches sur le Développement International (FERDI). [Google Scholar]

- Le, Thanh. 2011. Remittances for economic development: The investment perspective. Economic Modelling 28: 2409–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Thanh, and Philip M. Bodman. 2011. Remittances or technological diffusion: Which drives domestic gains from brain drain? Applied Economics 43: 2277–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hyun-Hoon, and John Ries. 2016. Aid for Trade and Greenfield Investment. World Development 84: 206–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limao, Nuno, and Anthony J. Venables. 2001. Infrastructure, geographical disadvantage, transport costs, and trade. World Bank Economic Review 15: 451–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limão, Nuno, and Giovanni Maggi. 2015. Uncertainty and Trade Agreements. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 7: 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Robert E. B., and Oded Stark. 1985. Motivations to remit: Evidence from Botswana. Journal of Political Economy 93: 901–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ly-My, Dung, and Hyun-Hoon Lee. 2019. Effects of aid for trade on extensive and intensive margins of greenfield FDI. The World Economy 42: 2120–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimbo, Samuel Munzele, Richard H. Adams, Jr., Reena Aggarwal, and Nikos Passas. 2005. Migrant Labour Remittance in the South Asia Region, Directions in Development. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, Candace, Michael E. Cummings, and Paul M. Vaaler. 2015. Economic informality and the venture funding impact of migrant remittances to developing countries. Journal of Business Venturing 30: 526–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melitz, Marc J., and Gianmarco I. P. Ottaviano. 2008. Market size, trade, and productivity. Review of Economic Studies 75: 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misati, Roseline Nyakerario, and Esman Morekwa Nyamongo. 2011. Financial development and private investment in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Economics and Business 63: 139–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, Pritha. 2006. Has Government Investment Crowded out Private Investment in India? American Economic Review 96: 337–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, Sanket, Caglar Ozden, Sonia Plaza, Dilip Ratha, Willia Shaw, and Abebe Shimeles. 2011. Leveraging Migration for Africa: Remittances, Skills, and Investments. Washington, DC: The World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey, Oliver, and Manop Udomkerdmongkol. 2012. Governance, Private Investment and Foreign Direct Investment in Developing Countries. World Development 40: 437–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, Subhadip, and Rupa Chanda. 2021. Tariff liberalization and firm-level markups in Indian manufacturing. Economic Modelling 103: 105594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Jochem Wilfried. 2021. Education and inspirational intuition–Drivers of innovation. Heliyon 7: e07923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munemo, Jonathan. 2022. Export entrepreneurship promotion: The role of regulation-induced time delays and institutions. International Review of Economics & Finance 77: 262–75. [Google Scholar]

- Naudé, Wim, Melissa Siegel, and Katrin Marchand. 2017. Migration, entrepreneurship, and development: Critical questions. IZA Journal of Migration 6: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, Thomas. 2021. The impact of entrepreneurship on economic, social, and environmental welfare and its determinants: A systematic review. Management Review Quarterly 71: 553–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Canh Phuc, Bach Nguyen, Bui Duy Tung, and Thanh Dinh Su. 2021. Economic complexity and entrepreneurship density: A non-linear effect study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 173: 121107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickell, Stephen. 1981. Biases in Dynamic Models with Fixed Effects. Econometrica 49: 1417–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouira, Ridha, Patrick Plane, and Khalid Sekkat. 2011. Exchange rate undervaluation and manufactured exports: A deliberate strategy? Journal of Comparative Economics 39: 584–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureen, Shabana, and Zafar Mahmood. 2022. The effects of trade cost components and uncertainty of time delay on bilateral export growth. Heliyon 8: e08779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novy, Dennis. 2013. Gravity Redux: Measuring International Trade Costs with Panel Data. Economic Inquiry 51: 101–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novy, Dennis, and Alan M. Taylor. 2020. Trade and Uncertainty. The Review of Economics and Statistics 102: 749–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Lehmann, Felicitas, and Elena Gross. 2021. Aid effectiveness: When aid spurs investment. Applied Economic Analysis 29: 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberhofer, Harald, and Michael Pfaffermayr. 2012. FDI versus Exports: Multiple Host Countries and Empirical Evidence. The World Economy 35: 316–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/WTO. 2011. Aid for Trade at a Glance 2011: Showing Results. Geneva: WTO. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, Rasmané, Relwendé Sawadogo, and Hamidou Sawadogo. 2020. Private and public investment in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of instability risks. Economic Systems 44: 100787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalia, Rosa Bernardini, and Silvia Bertarelli. 2015. Trade Costs in Bilateral Trade Flows: Heterogeneity and Zeroes in Structural Gravity Models. The World Economy 38: 1744–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piteli, Eleni E. N., Peter J. Buckley, and Mario Kafouros. 2019. Do remittances to emerging countries improve their economic development? Understanding the contingent role of culture. Journal of International Management 25: 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugal-Perez, Alberto, and John S. Wilson. 2012. Export Performance and Trade Facilitation Reform: Hard and Soft Infrastructure. World Development 40: 1295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramcharan, Rodney. 2006. Does Economic Diversification Lead to Financial Development? Evidence from Topography. IMF Working Paper WP/06/35. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, Hillel, and Frédéric Docquier. 2006. The economics of migrants’ remittances. In Handbook on the Economics of Reciprocity, Giving and Altruism. Edited by Serge-Christophe Kolm and Jean Mercier Ythier. Amsterdam: North-Holland, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ratha, Artatrana, and Masoud Moghaddam. 2020. Remittances and the Dutch disease phenomenon: Evidence from the bounds error correction modelling and a panel space. Applied Economics 52: 3327–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, David M. 2009. A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxford Bulletin of Economic and Statistics 71: 135–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadi, Mohamed. 2020. Remittance Inflows and Export Complexity: New Evidence from Developing and Emerging Countries. The Journal of Development Studies 56: 2266–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra-Pons, Pau, Irene Comeig, and Alicia Mas-Tur. 2022. Institutional factors affecting entrepreneurship: A QCA analysis. European Research on Management and Business Economics 28: 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, Alan Finkelstein, and Federico S. Mandelman. 2016. Remittances, entrepreneurship, and employment dynamics over the business cycle. Journal of International Economics 103: 184–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, Bedassa, Bichaka Fayissa, and Elias Shukralla. 2021. Infrastructure, Trade Costs, and Aid for Trade: The Imperatives for African Economies. Journal of African Development 22: 38–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajaddini, Reza, and Hassan F. Gholipour. 2021. Economic uncertainty and business formation: A cross-country analysis. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 16: e00274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teignier, Marc. 2018. The role of trade in structural transformation. Journal of Development Economics 130: 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, Mai Thi T., and Ekaterina Turkina. 2014. Macro-level determinants of formal entrepreneurship versus informal entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing 29: 490–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2010. Maximizing the Development Impact of Remittances. Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Vaaler, Paul M. 2011. Immigrant remittances and the venture investment environment of developing countries. Journal of International Business Studies 42: 1121–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaaler, Paul M. 2013. Diaspora concentration and the venture investment impact of remittances. Journal of International Management 19: 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijil, Mariana, and Laurent Wagner. 2012. Does Aid for Trade Enhance Export Performance? Investigating on the Infrastructure Channel. World Economy 35: 838–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, John S., Catherine L. Mann, and Tsunehiro Otsuki. 2003. Trade facilitation and economic development: A new approach to quantifying the impact. World Bank Economic Review 17: 367–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, John S., Catherine L. Mann, and Tsunehiro Otsuki. 2005. Assessing the benefits of trade facilitation: A global perspective. World Economy 28: 841–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, Christopher, and Rene Zenteno. 2007. Migration networks and microenterprises in Mexico. Journal of Development Economics 82: 509–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank, and KNOMAD. 2019. Migration and Remittances–Recent Developments and Outlook. Migration and Development Brief 31. April. Available online: https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2019–04/Migrationanddevelopmentbrief31.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- World Bank, and KNOMAD. 2021. Recovery–COVID-19 Crisis–Through a Migration Lens. Migration and Development Brief 35. November. Available online: https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2021–11/Migration_Brief%2035_1.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- World Trade Organization (WTO). 2005. Ministerial Declaration on Doha Work Programme. Paper presented at the Sixth Session of Trade Ministers Conference, Hong Kong, China, December 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yanase, Akihiko, and Masafumi Tsubuku. 2022. Trade costs and free trade agreements: Implications for tariff complementarity and welfare. International Review of Economics & Finance 78: 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Dean. 2008. International migration, remittances, and household investment: Evidence from Philippine migrants’ exchange rate shocks. Economic Journal 118: 591–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Dean. 2011. Migrant remittances. Journal of Economic Perspectives 25: 129–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, R. Isil, and Berrak Bahadir. 2022. Remittances, Ethnic Diversity, and Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries. Small Business Economics 58: 1931–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Congcong, and Martina Musteen. 2018. The Impact of Remittances on opportunity based and necessity based entrepreneurial activities. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal 24: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

| Static Model Specification | Dynamic Model Specification | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLS | FEs | FGLS | POLS | FEs | Two-Step System GMM | |

| Variables | RINV | RINV | RINV | RINV | RINV | RINV |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| RINVt−1 | 0.330 *** | 0.0931 *** | 0.193 *** | |||

| (0.0197) | (0.0243) | (0.0104) | ||||

| AfTTOTt−1 | 0.0208 *** | 0.0197 *** | 0.0261 *** | |||

| (0.00713) | (0.00748) | (0.00739) | ||||

| AfTTOT | 0.00470 | 0.00865 | 0.0848 *** | |||

| (0.00480) | (0.0144) | (0.0148) | ||||

| RNINV | 0.852 *** | 0.882 *** | 0.899 *** | 0.573 *** | 0.833 *** | 0.523 *** |

| (0.0209) | (0.0115) | (0.00820) | (0.0240) | (0.0166) | (0.0157) | |

| Non-AfTTOT | 0.108 *** | 0.0578 *** | 0.0947 *** | 0.0707 ** | 0.0322 | 0.0584 *** |

| (0.0302) | (0.0214) | (0.0128) | (0.0341) | (0.0214) | (0.0127) | |

| GDPC | 0.215 *** | 0.191 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.0871 | 0.109 * | 0.163 *** |

| (0.0727) | (0.0655) | (0.0240) | (0.0529) | (0.0632) | (0.0187) | |

| POP | 0.0326 | −0.318 | 0.00643 | 0.0104 | −0.363 | −0.0252 ** |

| (0.0233) | (0.284) | (0.0105) | (0.0227) | (0.274) | (0.0113) | |

| FINDEV | 0.206 *** | 0.177 *** | 0.220 *** | 0.156 *** | 0.160 *** | 0.205 *** |

| (0.0178) | (0.0328) | (0.0194) | (0.0125) | (0.0330) | (0.0250) | |

| REER | −0.00838 | −0.127 ** | 0.0752 ** | −0.109 *** | −0.139 *** | −0.180 *** |

| (0.0587) | (0.0570) | (0.0381) | (0.0411) | (0.0410) | (0.0503) | |

| TERMS | 0.0936 *** | 0.212 *** | 0.0903 *** | 0.0936 *** | 0.183 ** | 0.134*** |

| (0.0199) | (0.0746) | (0.0239) | (0.0276) | (0.0763) | (0.0335) | |

| DUMOUT | −0.521 *** | −0.315 *** | −0.346 *** | −0.412 *** | −0.262 *** | −1.044 *** |

| (0.0564) | (0.0564) | (0.0434) | (0.0824) | (0.0768) | (0.0557) | |

| Constant | −3.262 *** | 2.923 | −3.179 *** | −1.068 * | 4.478 | |

| (0.622) | (4.418) | (0.357) | (0.548) | (4.133) | ||

| Observations–Countries | 510–106 | 510–106 | 510–106 | 505–106 | 505–106 | 505–106 |

| R-squared/within R-squared | 0.927 | 0.8245 | 0.946 | 0.8167 | ||

| Pseudo-R-squared | 0.9626 | |||||

| AR1 (p-value) | 0.0073 | |||||

| AR2 (p-value) | 0.2017 | |||||

| OID (p-value) | 0.5144 | |||||

| Variables | RINV | RINV | RINV |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| RINVt−1 | 0.202 *** | 0.203 *** | 0.225 *** |

| (0.0115) | (0.0113) | (0.00947) | |

| AfTINFRA | 0.0529 *** | ||

| (0.00765) | |||

| AfTPROD | 0.0876 *** | ||

| (0.0132) | |||

| AfTPOL | 0.0369 *** | ||

| (0.00778) | |||

| RNINV | 0.533 *** | 0.509 *** | 0.473 *** |

| (0.0156) | (0.0138) | (0.0166) | |

| Non-AfTTOT | 0.0387 *** | 0.0633 *** | 0.111 *** |

| (0.0143) | (0.0134) | (0.0178) | |

| GDPC | 0.0864 *** | 0.135 *** | 0.0872 *** |

| (0.0219) | (0.0236) | (0.0273) | |

| POP | −0.0624 *** | −0.0171 | −0.0161 |

| (0.0129) | (0.0127) | (0.0132) | |

| FINDEV | 0.206 *** | 0.238 *** | 0.271 *** |

| (0.0222) | (0.0222) | (0.0246) | |

| REER | −0.178 *** | −0.160 *** | −0.312 *** |

| (0.0455) | (0.0573) | (0.0670) | |

| TERMS | 0.155 *** | 0.120 *** | 0.104 *** |

| (0.0460) | (0.0307) | (0.0399) | |

| DUMOUT | −1.041 *** | −0.923 *** | −1.094 *** |

| (0.0666) | (0.0552) | (0.0436) | |

| Observations–countries | 505–106 | 505–106 | 495–106 |

| AR (1) (p-value) | 0.0079 | 0.0049 | 0.0054 |

| AR (2) (p-value) | 0.1121 | 0.3034 | 0.10 |

| OID (p-value) | 0.5133 | 0.4793 | 0.3229 |

| Variables | RINV | RINV | RINV | RINV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| RINVt−1 | 0.197 *** | 0.203 *** | 0.193 *** | 0.213 *** |

| (0.0127) | (0.0123) | (0.0129) | (0.0120) | |

| AfTTOT | 0.0566 *** | |||

| (0.0145) | ||||

| AfTTOT × LDC | 0.118 *** | |||

| (0.0177) | ||||

| AfTINFRA | 0.0301 *** | |||

| (0.00921) | ||||

| AfTINFRA × LDC | 0.124 *** | |||

| (0.0137) | ||||

| AfTPROD | 0.0999 *** | |||

| (0.0117) | ||||

| AfTPROD × LDC | −0.0245 | |||

| (0.0155) | ||||

| AfTPOL | 0.0450 *** | |||

| (0.0128) | ||||

| AfTPOL × LDC | −0.0234 | |||

| (0.0149) | ||||

| LDC | 0.923 *** | 1.091 *** | 0.309 ** | 0.246 * |

| (0.123) | (0.102) | (0.138) | (0.145) | |

| RNINV | 0.566 *** | 0.584 *** | 0.549 *** | 0.535 *** |

| (0.0153) | (0.0137) | (0.0144) | (0.0159) | |

| Non-AfTTOT | 0.0617 *** | 0.0406 ** | 0.0592 *** | 0.114 *** |

| (0.0157) | (0.0194) | (0.0180) | (0.0227) | |

| GDPC | 0.349 *** | 0.292 *** | 0.338 *** | 0.297 *** |

| (0.0453) | (0.0479) | (0.0443) | (0.0415) | |

| POP | 0.00340 | −0.0348 ** | 0.0193 | 0.00703 |

| (0.0143) | (0.0176) | (0.0163) | (0.0164) | |

| FINDEV | 0.163 *** | 0.183 *** | 0.229 *** | 0.264 *** |

| (0.0318) | (0.0316) | (0.0316) | (0.0298) | |

| REER | −0.232 *** | −0.227 *** | −0.215 *** | −0.346 *** |

| (0.0566) | (0.0619) | (0.0482) | (0.0649) | |

| TERMS | 0.0911 ** | 0.119 ** | 0.0957 ** | 0.147 *** |

| (0.0448) | (0.0472) | (0.0429) | (0.0511) | |

| DUMOUT | −0.979 *** | −0.892 *** | −0.901 *** | −0.975 *** |

| (0.0441) | (0.0499) | (0.0478) | (0.0415) | |

| Observations–countries | 505–106 | 505–106 | 505–106 | 495–106 |

| AR (1) (p-value) | 0.0128 | 0.0186 | 0.0065 | 0.0073 |

| AR (2) (p-value) | 0.3398 | 0.2997 | 0.2960 | 0.10 |

| OID (p-value) | 0.4860 | 0.4372 | 0.3763 | 0.4930 |

| Variables | RINV | RINV |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| RINVt−1 | 0.200 *** | 0.195 *** |

| (0.00932) | (0.0171) | |

| AfTTOT | −0.258 *** | 0.101 *** |

| (0.0865) | (0.0254) | |

| AfTTOT × POP | 0.0193 *** | |

| (0.00555) | ||

| AfTTOT × DUMRINVSUP5 | 0.235 *** | |

| (0.0818) | ||

| DUMRINVSUP5 | 1.759 *** | |

| (0.422) | ||

| RNINV | 0.523 *** | 0.544 *** |

| (0.0161) | (0.0231) | |

| Non-AfTTOT | 0.0610 *** | 0.117 *** |

| (0.0129) | (0.0277) | |

| GDPC | 0.138 *** | 0.305 *** |

| (0.0203) | (0.0425) | |

| POP | 0.0773 ** | 0.00689 |

| (0.0372) | (0.0200) | |

| FINDEV | 0.212 *** | 0.132 *** |

| (0.0217) | (0.0481) | |

| REER | −0.226 *** | −0.0685 |

| (0.0455) | (0.0767) | |

| TERMS | 0.108 *** | 0.124 ** |

| (0.0298) | (0.0552) | |

| DUMOUT | −1.031 *** | −1.091 *** |

| (0.0533) | (0.0698) | |

| Observations–countries | 505–106 | 505–106 |

| AR (1) (p-value) | 0.0061 | 0.0085 |

| AR (2) (p-value) | 0.1812 | 0.3221 |

| OID (p-value) | 0.4569 | 0.5049 |

| Variables | RINV | RINV | RINV | RINV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| RINVt−1 | 0.185 *** | 0.182 *** | 0.244 *** | 0.192 *** |

| (0.0128) | (0.0103) | (0.0143) | (0.00905) | |

| AfTTOT | 0.0434 ** | −0.766 *** | −0.0430 | −0.363 ** |

| (0.0195) | (0.119) | (0.0365) | (0.153) | |

| TRCOST | −0.724 *** | 0.446 *** | ||

| (0.129) | (0.173) | |||

| AfTTOT × TRCOST | 0.143 *** | |||

| (0.0210) | ||||

| AfTTOT × TARIFF | 1.042 *** | |||

| (0.373) | ||||

| TARIFF | 5.469 ** | |||

| (2.255) | ||||

| AfTTOT × NTARIFF | 0.0702 ** | |||

| (0.0273) | ||||

| NTARIFF | −0.125 | |||

| (0.158) | ||||

| RNINV | 0.641 *** | 0.636 *** | 0.560*** | 0.626 *** |

| (0.0200) | (0.0145) | (0.0178) | (0.0122) | |

| Non-AfTTOT | −0.0310 | 0.00136 | 0.0144 | 0.0186 |

| (0.0219) | (0.0180) | (0.0223) | (0.0194) | |

| GDPC | −0.0497 | 0.0235 | 0.150 *** | 0.0113 |

| (0.0399) | (0.0373) | (0.0462) | (0.0373) | |

| POP | −0.108 *** | −0.100 *** | −0.0140 | −0.0796 *** |

| (0.0169) | (0.0174) | (0.0158) | (0.0131) | |

| FINDEV | 0.112 *** | 0.116 *** | −0.0126 | 0.120 *** |

| (0.0312) | (0.0265) | (0.0436) | (0.0242) | |

| REER | 0.0166 | 0.0481 | −0.0632 | −0.0339 |

| (0.0801) | (0.0630) | (0.0398) | (0.0636) | |

| TERMS | 0.0408 | 0.0800 * | 0.0176 | 0.0372 |

| (0.0482) | (0.0476) | (0.0356) | (0.0386) | |

| DUMOUT | −0.670 *** | −0.719 *** | −0.878 *** | −0.717 *** |

| (0.0599) | (0.0516) | (0.0570) | (0.0464) | |

| Observations–countries | 470–103 | 470–103 | 475–100 | 455–100 |

| AR (1) (p-value) | 0.0228 | 0.0129 | 0.0155 | 0.0466 |

| AR (2) (p-value) | 0.1733 | 0.1716 | 0.2249 | 0.2822 |

| OID (p-value) | 0.3481 | 0.4091 | 0.4618 | 0.4884 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gnangnon, S.K. Effect of Aid-for-Trade Flows on Investment-Oriented Remittance Flows. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2023, 16, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16020110

Gnangnon SK. Effect of Aid-for-Trade Flows on Investment-Oriented Remittance Flows. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2023; 16(2):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16020110

Chicago/Turabian StyleGnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2023. "Effect of Aid-for-Trade Flows on Investment-Oriented Remittance Flows" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16, no. 2: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16020110

APA StyleGnangnon, S. K. (2023). Effect of Aid-for-Trade Flows on Investment-Oriented Remittance Flows. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(2), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16020110