Abstract

This study delves into the relationships between the perception of corporate social responsibility (PCSR), organizational commitment and employee innovation behavior, as well as the multiple mediating roles of affective, normative and continuance commitment in the relationship between the perception of CSR and innovation behavior. This research involved 419 employees from 15 artificial intelligence (AI) enterprises in Shenzhen, China. This study’s hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling. The findings indicate that PCSR significantly impacts innovation behavior, and affective, continuance and normative commitments also positively influence innovation behavior. Moreover, these three commitments play a partial mediating role in the relationship between PCSR and innovation behavior. This study enriches and expands the understanding of the multiple mediating mechanisms between PCSR and employee innovation behavior, providing a theoretical basis and guidance for management to comprehensively understand the role of employees’ PCSR in enhancing organizational commitment and fostering innovation behavior.

1. Introduction

Organizations face unprecedented opportunities and challenges in today’s era of rapid technological advancement (You et al. 2022; Flammer and Kacperczyk 2019). The significance of innovation is increasingly highlighted in organizations’ continual pursuit of sustainable competitive advantage (Li et al. 2023). The main asset of an organization is its employees (Cachón-Rodríguez et al. 2022). Innovation must be realized through innovative behavior. In today’s dynamic and cutthroat corporate circumstances, employee innovation behavior is essential to organizational success (Pujianto and Musyaffaah 2023).

Furthermore, as an integral part of the social system (Fernando et al. 2019), businesses must participate in socially conscious endeavors to facilitate their expansion (Barauskaite and Streimikiene 2021). Businesses are increasingly aware that social responsibility is related to enterprises’ fundamental interests and long-term development, and they consciously assume corporate social responsibilities (hereafter referred to as CSR) (Li et al. 2020; Ait Sidhoum and Serra 2018).

Employees’ values have also changed significantly, with subjective needs becoming more diverse and complex. Employees no longer solely pursue economic benefits; their perception of CSR initiatives undertaken by their organizations has become a pivotal factor influencing their attitudes and behaviors (Orazalin 2020; Van Dick et al. 2020). Consequently, does this stimulating factor also positively affect employees’ innovative behaviors? Existing research indicates a direct relationship between employees’ perceptions of CSR (hereafter referred to as PCSR) and their innovation (Hur et al. 2018; Li et al. 2020). However, the internal mechanisms linking PCSR and employee innovation behavior require further exploration (Wu et al. 2022; Chen and Zhang 2023).

Organizational commitment is frequently employed as a crucial psychological link in research on organizational behavior and attitudes (Lu et al. 2020). It represents employees’ significant intrinsic psychological attitudes (Wu and Chen 2018; Ahmed and Tahir 2019) and is related to organizational outcomes. Some studies indicate that PCSR may influence employees’ organizational commitments (Kong et al. 2019; George et al. 2021; Tran et al. 2021; Li and Qu 2023; Silva et al. 2023), while other research indicates that organizational commitment plays a crucial role in employees’ innovative initiatives (Nazir et al. 2018; Fauziawati 2021; Sharma et al. 2021; Chen and Liu 2022; Li and Qu 2023; Chtioui et al. 2023; Chen and Zhang 2023). Furthermore, studies reveal that employees are more likely to believe that the organization will treat them fairly and justly if they perceive the organization as treating key stakeholders ethically (Kim and Lee 2022). Employees are more likely to develop positive organizational commitments (Stojanovic et al. 2020) and respond with positive work behaviors (Choi et al. 2018). Thus, a mediating link between employee innovation behavior, PCSR and organizational commitment may exist.

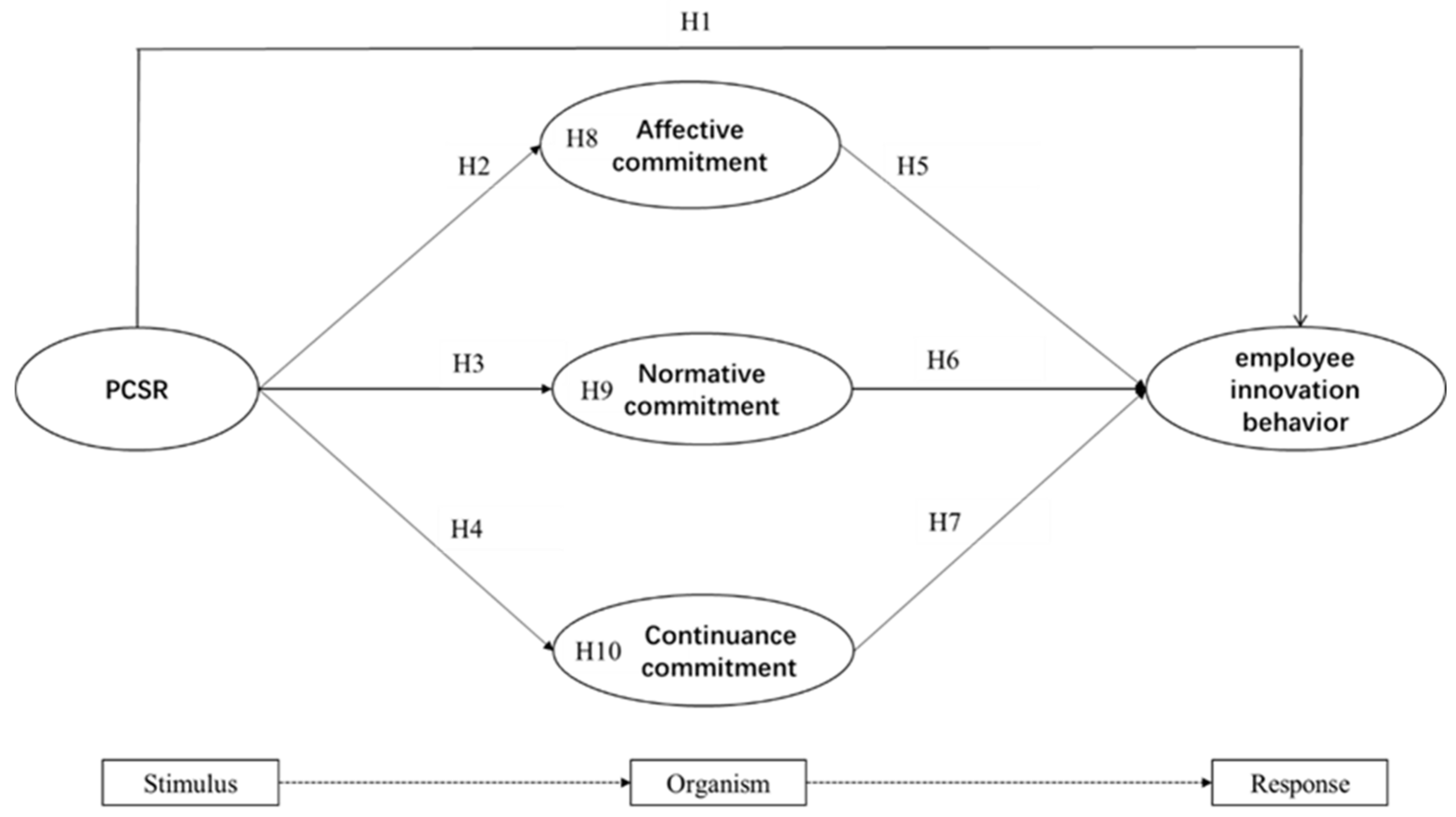

This study utilizes the stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) theory to examine the relationships among PCSR, organizational commitment and employee innovation behavior. The S-O-R theory framework, originating in behavioral psychology, is extensively applied in organizational behavior research (Ahmed et al. 2020; Huang et al. 2022). The S-O-R framework can be used to analyze how environmental stimuli effectively influence individuals’ internal states, subsequently eliciting individual behaviors (Xu and Wang 2020). In the organizational context of the S-O-R theoretical framework, stimuli encompass all external factors that induce employee changes (Tang et al. 2019; Yin et al. 2021). PCSR is considered a type of stimulus (Wu et al. 2022; Chen and Zhang 2023; Nguyen-Viet et al. 2024). At the same time, the S-O-R framework further indicates that the organism typically acts as a mediator between stimulus and response (Bigne et al. 2020). Psychological states often represent the organism (Ahn and Seo 2018; Leung and Wen 2020; Leung et al. 2021). The response (R) represents the outcome, including various behavioral feedback responses (Chen and Zhang 2023). Following this logic, employees’ perceptions affect their behaviors through mediating factors, usually psychological attitudes (Wu et al. 2022; Chen and Zhang 2023). Organizational commitment is regarded as a psychological attitude of employees (Ahmed and Tahir 2019; Wu and Chen 2018; Chen and Zhang 2023). The concept of commitment is commonly divided into affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment (George et al. 2021). Some studies have also confirmed the efficacy of organizational commitment as a mediating variable (Fauziawati 2021; Chen and Liu 2022; Li and Qu 2023). Therefore, we predict that organizational commitment positively impacts employee innovation behavior and mediates between PCSR and employee innovation behavior. We utilize the S-O-R framework to analyze the connection between PCSR as a stimulus and employee innovation behavior as a response, along with the mediating role of organizational commitment (organism) in this relationship.

The survey population for this study consists of employees from AI enterprises in Shenzhen, China. Presently, China possesses the world’s second-largest cluster of artificial intelligence enterprises and has emerged as one of the global leaders in the AI industry (Dong et al. 2020). As a key city in China’s AI industry, Shenzhen has become a leader in setting domestic AI industry standards (Li 2024). As of April 2024, Shenzhen has led or participated in formulating six out of ten national standards published in the AI field and has ranked first in international patent applications among Chinese cities for 20 consecutive years (Li 2024; He 2024). Due to the need for economic transformation, China places a heightened emphasis on artificial intelligence. The AI industry relies on continuous innovation to survive in a competitive landscape (Dong et al. 2020). However, research analyzing the innovation development of Chinese AI enterprises is quite limited (Arenal et al. 2020), highlighting the necessity to address the gap in studies on employee innovation behavior in Chinese AI enterprises. Shenzhen, China’s next-generation AI innovation development experimental zone and a national AI innovation application pilot zone (Shenzhen Artificial Intelligence Industry Association 2024), provides an appropriate context to study the relationships among employees’ PCSR, organizational commitment and innovation behavior.

Therefore, this study uses multiple mediation analyses to examine the relationship and influence paths between PCSR and employee innovation behaviors in AI firms in Shenzhen. It also aims to confirm whether different types of organizational commitments mediate the relationship between PCSR and employee innovation behaviors. Although CSR has existed for over 60 years, research on CSR has grown significantly recently (Escamilla-Solano et al. 2023). The findings of this study expand research on CSR at the micro level. Although existing literature has utilized the S-O-R framework to examine the relationship between PCSR and employee behavior, it has primarily focused on organizational trust (Nguyen-Viet et al. 2024), organizational identification (Wu et al. 2022), work enthusiasm (Alhumoudi et al. 2023), and well-being (Su and Swanson 2019; Ahmed et al. 2020). The S-O-R framework is used in this study to show how PCSR can lead to innovation behavior through the important role of organizational commitment. It gives us a new way to think about how CSR affects employee behavior and adds to our understanding of how the different aspects of organizational commitment strengthen the effect of PCSR on innovation behavior. This study also adds to the S-O-R literature and expands the S-O-R framework. Additionally, by selecting the organizational context of Chinese AI enterprises, this study enriches and optimizes the sample pool for research on organizational commitment and employee innovation behavior within the Chinese context. It also provides more comprehensive insights into the interactions among Chinese employees’ PCSR, the dimensions of organizational commitment and innovation behavior.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

This study explores the relationships between employees’ PCSR, organizational commitment and innovation behavior based on the stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) theoretical framework. Mehrabian and Russell (1974) proposed the S-O-R framework based on stimulus–response theory, positing that environmental stimuli influence an individual’s internal state, affecting their behavior. The S-O-R framework provides insights into how stimuli shape internal states in the human environment and influence responses represented by behavior (Chen and Zhang 2023). According to the S-O-R theory, changes in internal drives and mechanisms brought about by external stimuli determine human behavior (Pandita et al. 2021). When individuals receive stimuli, internal psychological processes are activated, leading to behavioral changes (Ferdous et al. 2021). Under certain stimulus conditions, a person typically generates corresponding subsequent behaviors mediated by an internal state (Ahmad et al. 2021). In other words, the organism often acts as an intermediary between stimulus and response (Bigne et al. 2020).

Studies utilizing the S-O-R framework model have increasingly enriched and been widely applied in organizational behavior research (Laesser et al. 2019; Ahmed et al. 2020; Huang et al. 2022). In the existing research, the PCSR has been confirmed as one of the external stimuli employees receive (Wu et al. 2022; Nguyen-Viet et al. 2024; Chen and Zhang 2023). The organism is considered an individual’s internal state after exposure to these stimuli, representing a psychological state or mechanism (Ahn and Seo 2018; Leung and Wen 2020; Leung et al. 2021). Therefore, in the relationship between PCSR and innovation behavior, PCSR can be regarded as a stimulus influencing employee behavior and response (Ahmad et al. 2021). As an important part of employees’ mental health, organizational commitment can be seen as an organism (Ahmed and Tahir 2019; Wu and Chen 2018; Lu et al. 2020; Chen and Zhang 2023) that serves as a mediator in these relationships linking the effects of PCSR (S) to employee innovative behavior (R). Therefore, this study considers the S-O-R framework as suitable for explaining the relationship between employees’ PCSR, organizational commitment and innovation behavior.

2.2. Perceptions of CSR and Employee Innovation Behavior

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has been widely discussed in global business, but there is yet to be a universally accepted definition of CSR (Barauskaite and Streimikiene 2021). Carroll (1979) defines CSR as the societal expectations placed on organizations at a particular time regarding economic, legal, ethical and voluntary obligations. El Akremi et al. (2018) view CSR as targeted organizational activities and policies that aim to improve stakeholders’ well-being by considering the triple bottom line of economic, social and environmental performance. CSR guides and encourages companies to behave more responsibly, positively impacting stakeholders such as the environment, customers, employees and communities. By fulfilling social responsibilities, companies can achieve sustainability in their business strategies (Ahmed and Tahir 2019). Barauskaite and Streimikiene (2021) stated that CSR should be considered a broad process. Socially responsible businesses align their interests with those of shareholders, employees, consumers, the environment, communities and other stakeholders.

Research has shown that CSR can yield macro-level outcomes but can also be seen as a micro-level issue related to employee outcomes (Hur et al. 2018; Escamilla-Solano et al. 2023). When conducting micro-level studies of CSR, it is crucial to understand employees’ perceptions of corporate CSR behaviors. Employees’ cognitive view of CSR is commonly called their perception of CSR (PCSR) (Ng et al. 2019; Hur et al. 2018). Even though both objective CSR and PCSR are important, PCSR may have a bigger effect on how employees react than objective, real CSR actions that employees may need to be made aware of (Gond et al. 2017), which can have a significant effect on how employees feel, what they do and how well they do their job (Hur et al. 2018). PCSR, as a predictor of various work outcomes, consistently outperforms objective CSR (Ng et al. 2019). Therefore, this study conducts an analysis based on PCSR, which is PCSR as employees’ subjective feelings and opinions on the CSR measures implemented by the organization.

Employee innovation behavior, as a form of employee behavioral outcomes, has garnered widespread attention in recent years. Employee innovation behavior was defined by Scott and Bruce (1994) as the actions of employees in developing, launching or implementing innovative strategies, procedures, services or products at work. Kwon and Kim (2020) define innovation behavior as the deliberate proposal and application of new and better ideas, procedures, practices and policies to achieve long-term sustainability, corporate success and organizational effectiveness. Innovation behavior is also considered an additional role or discretionary action (Cho and Song 2021). Proposing and implementing new and better ideas, procedures, practices and policies for the organization’s efficacy, financial success and long-term sustainability is a conscious representation of employee innovation behavior (Nazir et al. 2018); it represents spontaneous actions to improve or create new situations.

Researchers have indicated that implementing CSR can alter employees’ attitudes and behaviors (Tong et al. 2019). CSR can enhance employees’ creativity by influencing their perceptions of the work environment (Kim and Lee 2022). Companies actively engaged in CSR typically advocate for a work atmosphere that is unrestricted and liberating (Rongbin et al. 2022). CSR activities of a company can also create an environment of confidence and trust for employees, enabling them to take risks without fearing negative consequences (Mao et al. 2021), thus making them more inclined to engage in innovative behaviors and produce more innovative products and services that benefit both the company and the community (Rongbin et al. 2022). CSR practices also communicate a positive corporate image and reputation to employees (Ali et al. 2020; Javed et al. 2020), which employees internalize as part of their values, making them more willing to embrace opportunities and challenges and thereby encouraging more innovative behaviors (De Roeck and Farooq 2018). Simultaneously, the implementation of CSR is an organizational learning process. In fulfilling their CSR, organizations must coordinate relationships among various stakeholders, foster a more open organizational culture, and promote communication and interaction internally and externally, which helps employees generate innovation behaviors (Li et al. 2020). Richter et al. (2021) argue that companies’ long-term CSR investment behaviors can stimulate the drive for product innovation, development, and differentiation.

Furthermore, CSR can increase the social acceptance of an organization, leading to higher-quality relationships within the institution and more being conducive to building social capital (Blanco-Gonzalez et al. 2020). Social capital is a driving factor in innovation development (Pylypenko et al. 2023). Through information exchange and technical cooperation, employees with social capital can affect team or organizational operations. They can also obtain more industry and market information, stimulating employees’ innovation behavior (Zhao et al. 2022). The following hypotheses are put forth in light of the study above:

H1.

PCSR positively influences employee innovation behavior.

2.3. Perceptions of CSR and Organizational Commitment

Employees’ attachments to the organization and their jobs are characterized by a psychological condition called organizational commitment (Ahmed and Tahir 2019; Wu and Chen 2018). Organizational commitment was characterized by Mowday et al. (1979) as a strong desire to stay a member, a readiness to invest significant work for the organization, and a staunch belief and acceptance of the organization’s aims and ideals. Employee commitment encompasses employees’ desires, feelings, and beliefs about participating in the organization. It goes beyond mere alignment with goals and values; it also involves obligations, needs, and desires to demonstrate involvement with the company (Ahmed and Tahir 2019). Meyer and Allen (1991) postulated three categories of organizational commitment: affective commitment, normative commitment and continuance commitment. Affective commitment is the term used to describe a person’s identity, emotional attachment and participation in their employment. Normative commitment is the feeling of duty a person has to their organization. Continuance commitment indicates that employees believe they need to stay with the organization. Employees who demonstrate continuance commitment are loyal to their organization and willing to stay with it (Zaman and Nadeem 2019; George et al. 2021). These three commitments each have distinct assessment criteria and represent the various psychological states of particular employees (Ahmed and Tahir 2019).

Kim and Lee (2022) point out that CSR engagement conveys positive values. Employees are more committed to the organization when they actively believe in its principles, since they are reluctant to leave a place where they have a great work environment. Altruistic CSR attribution positively impacts employees’ attitudes. Employees will feel pleased to work for a business if various stakeholders value and acknowledge its CSR initiatives and social standing (Tian and Robertson 2019). When CSR projects or behaviors meet employees’ expectations, they can enhance individuals’ self-worth and satisfy their pursuit of positive self-esteem. They could be more committed to the organization because of their improved attitude (Khan et al. 2021). Employees’ favorable perceptions of organizational CSR ought to result in a favorable perception of organizational justice (George et al. 2020), thereby enhancing emotional connections to the company and deepening a sense of responsibility (Diatmono 2019), contributing to forming normative commitment.

Furthermore, investing resources in social and charitable activities or employee care can enhance employees’ happiness, positively impacting their commitment (Wu et al. 2019; Ahmed and Tahir 2019). According to Tran et al.’s (2021) research, employees’ affective commitments increase with their levels of empowerment, health and safety, job satisfaction and work–life balance. CSR also helps to build social capital (Blanco-Gonzalez et al. 2020). Social capital is a resource that retains members within an organization (Cachón-Rodríguez et al. 2022). According to Barauskaite and Streimikiene (2021), CSR can also support corporate sustainable development. Employees’ long-term loyalty to the company will increase when they accept socially responsible actions (Cachón-Rodríguez et al. 2022), strengthening their continuance commitment. The following hypotheses are put forth in light of the study above:

H2.

PCSR positively influences affective commitment.

H3.

PCSR positively influences normative commitment.

H4.

PCSR positively influences continuance commitment.

2.4. Organizational Commitment and Employee Innovation Behavior

Positive behaviors are the outcomes of positive attitudes (Khaleel et al. 2017). Employees with positive psychological attitudes toward the organization actively engage in the company’s success and sustainability, leading to positive actions (Wu et al. 2022). Organizational commitment, in essence, reflects employees’ positive psychological attitudes towards the organization, indicating their willingness to participate and become part of the organization (Wu and Chen 2018; Ahmed and Tahir 2019; Lu et al. 2020). Highly effective commitment employees had a higher chance of long-term employment retention and good work behaviors (Ghasempour Ganji et al. 2021). Employees with a strong normative commitment also typically show greater satisfaction and loyalty (Cao 2023). Loyal employees in the company exhibit positive extra-role behaviors, including innovation behavior. They also tend to be good achievers, innovating, developing and satisfying customers’ expectations (Cho and Song 2021). The following hypotheses are put forth in light of the study above:

H5.

Affective commitment positively influences employee innovation behavior.

H6.

Normative commitment positively influences employee innovation behavior.

H7.

Continuance commitment positively influences employee innovation behavior.

2.5. The Mediation Role of Organizational Commitment

The S-O-R theory explains the relationship between employees’ PCSR, organizational commitment and innovation behavior. The S-O-R theory has been widely applied in studies of employee behavior (Attiq et al. 2017). The S-O-R theory emphasizes that human behavioral responses are complex (Zhu et al. 2020). Individuals will exhibit corresponding follow-up behaviors in response to specific stimulus conditions, which require cognitive processes mediated by conduction (Bigne et al. 2020; Wu et al. 2022; Chen and Zhang 2023). In other words, the human behavioral process involves a sequence from stimulus to changes in psychological state and then to action response (Ferdous et al. 2021; Ahmad et al. 2021). Employees’ PCSR can be considered a stimulus factor (Wu et al. 2022; Nguyen-Viet et al. 2024; Chen and Zhang 2023), influencing both their organizational commitment (O) and their innovation behavior (R). According to Ahmed and Tahir (2019) and Lu et al. (2020), organizational commitment, which acts as an organism (O) in the S-O-R framework, describes how a person thinks about and reacts to their surroundings. It mediates the connection between PCSR (S) and employee innovation behavior (R). Many scholars in previous studies have confirmed the mediating role of organizational commitment as an intermediate variable (Fauziawati 2021; Chen and Liu 2022; Li and Qu 2023). Based on the above analysis and incorporating the three-factor structure theory of organizational commitment, the following hypotheses are put forth in this study:

H8.

Affective commitment mediates the relationship between PCSR and employee innovation behavior.

H9.

Normative commitment mediates the relationship between PCSR and employee innovation behavior.

H10.

Continuance commitment mediates the relationship between PCSR and employee innovation behavior.

Based on this study’s theoretical framework and literature review, Figure 1 shows this study’s complete theoretical model and research hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model and research hypotheses.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

This study’s sample data were collected from AI enterprise employees in Shenzhen, China. China is undergoing economic transformation, driving increased attention toward artificial intelligence (AI) due to its capability to overcome the physical limitations of capital and labor, thereby opening up new sources of value and growth (Arenal et al. 2020). Consequently, the AI industry is rapidly expanding in China. According to the “Artificial Intelligence Development White Paper” published by the Shenzhen Artificial Intelligence Industry Association (2024), China ranks second globally in the number of AI companies. Shenzhen is recognized as one of the key cities for AI development in China, serving as a leader and demonstration area in developing the Chinese AI industry (Shenzhen Artificial Intelligence Industry Association 2024). It has achieved significant results in AI-related policy-making on the industry scale, as well as technological innovation (Li 2024; He 2024). Innovation primarily drives AI enterprises (Dong et al. 2020). This study selects employees of AI companies in Shenzhen as the research subjects for employee innovation behavior, which is representative and can effectively achieve the research objectives.

This study utilized questionnaire surveys to collect data. At the end of 2023, AI companies in Shenzhen employed approximately 140,000 employees (Shenzhen Artificial Intelligence Industry Association 2024). Following the method used by Krejcie and Morgan (1970) to determine the minimum sample size, the calculated minimum sample size was 385 individuals. To account for potentially invalid data in the returned questionnaires, the study planned to distribute 450 questionnaires to ensure that the number of valid responses was equal to or greater than 385.

During the sampling process, according to the “Artificial Intelligence Security Standardization White Paper (2019 Edition)” issued by the China Information Security Standardization Technical Committee (2019), the artificial intelligence industry chain is primarily divided into three levels: the basic layer, the technical layer and the application layer. Therefore, we first stratified the AI enterprises in Shenzhen according to these three layers. Based on the “2024 Artificial Intelligence Development White Paper” and data from the Qichacha database, it was found that by the end of 2023, approximately 20% of Shenzhen’s AI companies were in the basic layer, 15.6% were in the technical layer and 64.6% were in the application layer. This distribution determined the number of questionnaires to be distributed for each layer: 90 for the basic layer, 70 for the technical layer, and 290 for the application layer, totaling 450. After data stratification, we extracted detailed information on enterprises in each layer from the Qichacha database. Then, we randomly sorted the enterprises and allocated corresponding number ranges based on the scale ratio of each company. Subsequently, we randomly selected these numbers and distributed questionnaires to the companies falling within the selected number ranges. Each number corresponded to one sampling opportunity, and for each random sampling, the sample unit consisted of 10 employees. Ultimately, we distributed 90 questionnaires to the basic layer, involving 4 enterprises; 70 questionnaires to the technical layer, involving 2 enterprises; and 290 questionnaires to the application layer, involving 9 enterprises. A total of 450 questionnaires were distributed to 15 enterprises.

Before the survey, the researcher explained the academic purpose to each participant and assured them that their answers would be kept confidential and used for academic purposes only. All the participants provided consent. There were two stages to the data-gathering process: the participants filled out Questionnaire A in the first phase, including data on PCSR and demographic factors. Questionnaire B on employee organizational commitment and innovation behavior was distributed to the participants one month later for the second stage. Before formally distributing the questionnaires, we conducted a small-scale offline pilot test. In the pilot test, we assessed the reliability and validity of the questionnaire and confirmed the stability and consistency of the scales. The questionnaire’s reliability and validity were validated by analyzing the pilot test with a small sample, consistent with the hypotheses. Therefore, we confirmed the applicability of the questionnaire and used it as the survey instrument for data collection. After excluding invalid questionnaires, we obtained a final count of 419 valid questionnaires, resulting in an overall response rate of 93%.

The demographic information of the participants is shown in Table 1. Among the survey participants, there were 222 males and 197 females, with 80% of the respondents primarily below the age of 40 years. More than 50% of the employees had 4 to 6 years of work experience. Employees with a bachelor’s degree or higher accounted for approximately 85.7% of the sample. It can be observed that the gender ratio in the survey sample was balanced, with the majority of the respondents being young and middle-aged, having considerable tenure in the company, and possessing a deep understanding and experience of their work and the company. Furthermore, most of them had received higher education, indicating a certain understanding of the concepts involved in this study. They were the primary drivers of innovative organizational initiatives and demonstrated high CSR participation.

Table 1.

Demographic variable data.

3.2. Variable Measurement

This study employed the traditional “translate–back-translate” method to convert the English survey questionnaire into Chinese, ensuring that the Chinese participants could understand the questionnaire items accurately. We used a Likert five-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”) to obtain responses from the participants. The measure scales for each variable are described below.

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in this study was employee innovation behavior (abbreviated as EB), measured using a six-item scale from Iqbal et al. (2020), derived from the classic scale by Scott and Bruce (1994). The sample items for this scale included “I will actively seek to apply new technologies, procedures, or methods”. For detailed scale item contents, please refer to Appendix A.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

The independent variable in this study was PCSR. The scale for measuring this variable was sourced from Tian and Robertson (2019) and derived from the classic scale by Turker (2009). This scale included 12 items, with sample items such as “Our company contributes to endeavors and projects that promote societal well-being”. For detailed scale item contents, please refer to Appendix A.

3.2.3. Mediating Variable

The mediating variables in this study were affective commitment (AC), normative commitment (NC) and continuance commitment (CC). The scales used to measure these variables originated from Loan (2020), based on the traditional three-factor organizational commitment scale developed by Meyer et al. (1993). Each commitment scale comprised six items, with sample items such as “I feel emotionally bonded with my company”, “I feel the obligation to remain with my current employer” and “Currently, staying with my company is a matter of necessity as much as desire”. For detailed scale item contents, please refer to Appendix A.

3.3. CMB Test

Using self-reported data may introduce CMB (Kim and Lee 2022). However, this study conducted the Harman single-factor test (Podsakoff and Organ 1986), revealing that the variance explained by the first factor prior to rotation was less than 50%. Additionally, the correlation coefficients among the constructs were all below 0.90, indicating that CMB is not significant in this study.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

This study conducted a descriptive analysis test. As shown in Table 2, it is clear that all the variable mean values were greater than 3. Among these, employee innovation behavior had the lowest mean value, and PCSR had the highest, demonstrating a high degree of agreement and readiness to engage among the respondents. Most of the items’ standard deviations fell between 0.8 and 1, indicating a somewhat concentrated data distribution with a moderate dispersion. The tolerance values of the independent variables were all above 0.20, and the VIF values were below 10, indicating that no multicollinearity issues among the variables were found (Thompson et al. 2017).

Table 2.

Descriptive analyses.

4.2. Reliability and Validity Test

This study conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) before testing the hypotheses. The Cronbach’s alpha values for all the constructs in Table 3 were higher than 0.70, the composite reliability (CR) value was higher than 0.8 and the average variance extracted (AVE) value was higher than 0.50. The measurement model is reliable and convergent (Fornell and Larcker 1981; Kim and Lee 2022). As shown in Table 4, the correlation coefficient between each variable was less than the square root of the AVE value. Therefore, the measurement model of this study had strong discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981). The questionnaire reached acceptable levels for the study in various reliability and validity indicators, indicating good reliability and validity. Additionally, the relationships among the variables were significantly positively correlated (Table 4), providing preliminary support for our hypotheses.

Table 3.

Convergent reliability and validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

4.3. Structural Model Fit Test

This study used a structural equation model, which was tested using the maximum likelihood estimation method. The fit indices for the structural route model used in this study are shown in Table 5. All the fit indices combined were within the typical range. The model had excellent goodness of fit (Hu and Bentler 1998).

Table 5.

Results of model fit test.

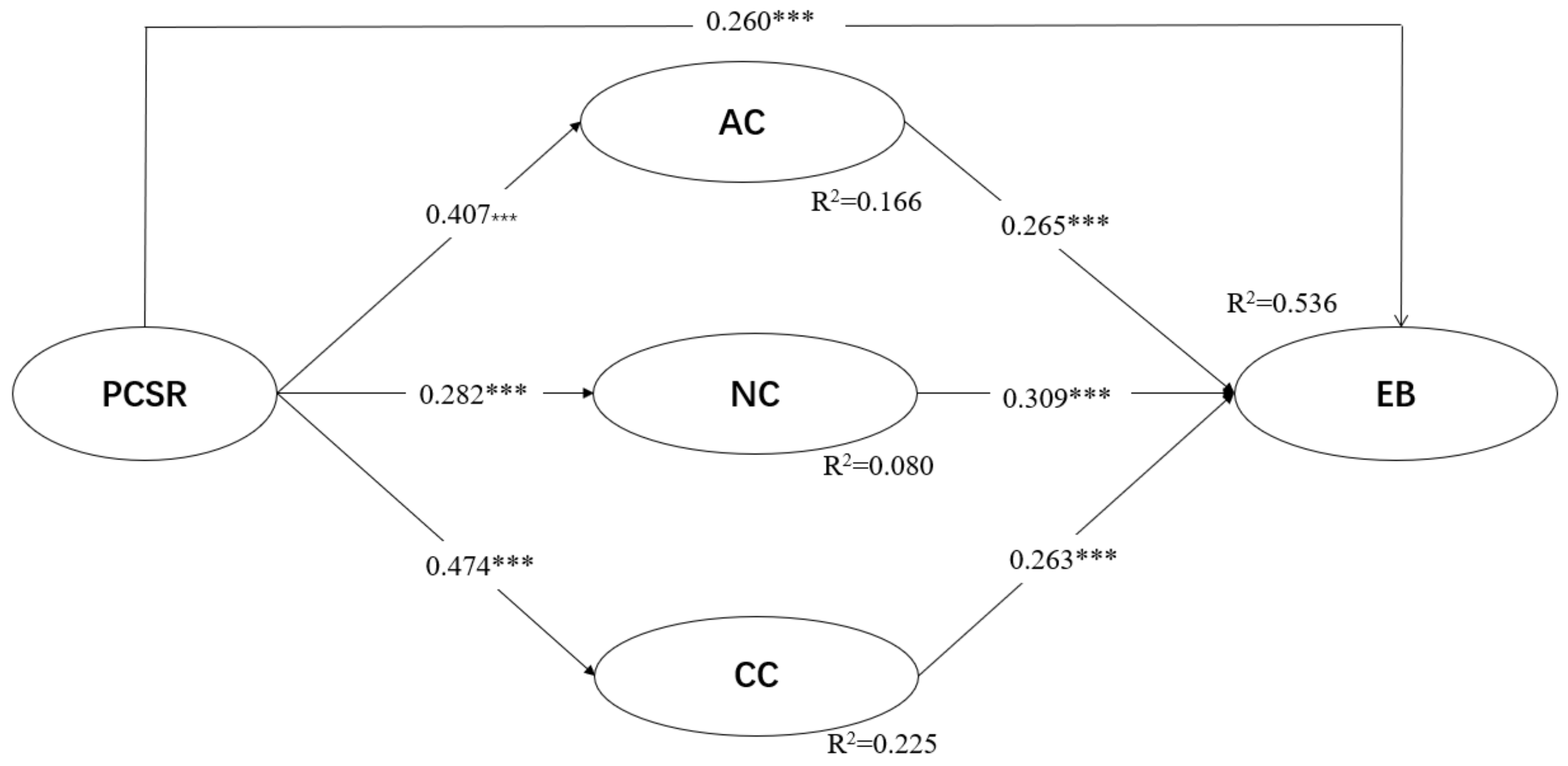

4.4. Path Analysis and Hypothesis Test

To validate these hypotheses, we first conducted a path analysis. Table 6 and Figure 2 display the path coefficients and significance levels. The analysis results show that PCSR had a significant positive impact on EB, thus supporting H1. Additionally, PCSR had a significant positive impact on AC, NC and CC, with PCSR having the strongest impact on continuance commitment. These result supports hypotheses H2, H3 and H4. AC, NC and CC also had significant positive impacts on EB, with normative commitment having the strongest impact on employee innovation behavior, thus supporting hypotheses H5, H6 and H7.

Table 6.

Standardized path estimates and hypothetical results.

Figure 2.

Path parameters of the research model. *** p < 0.001.

4.5. Mediation Effect Analysis

This study used the Bootstrap method, which is widely acknowledged as an efficient technique for analyzing mediation effects. A total of 5000 bootstrap resamples were specifically run to extensively analyze the numerous mediation effects in the model. A 95% bias-corrected confidence interval was produced using technique (BC 95% CI). Comprehensive data on total, direct and indirect impacts are included in Table 7.

Table 7.

Total, direct and indirect effects.

The mediation analysis results indicate that all the paths of indirect effects were significant, along with significant direct effects. Therefore, affective, normative and continuance commitment partially mediate the relationship between PCSR and employee innovation behavior, confirming H8 to H10.

In summary, the results of this study demonstrate that the questionnaire was reliable and valid, and the model fit well. All the paths showed significant impact effects, indicating the presence of mediating effects. Therefore, all the hypotheses proposed in this study were validated.

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings and Theoretical Contributions

This study aimed to analyze how employees’ PCSR influences their innovation behavior and to explore the multiple mediating roles of organizational commitment between PCSR and employee innovation behavior. Specifically, this research focused on a micro-level study of CSR, where employees’ emotional responses and behaviors towards CSR are shaped by their cognitive evaluations rather than merely the objective level of CSR activities. Therefore, when approaching CSR from a micro perspective rather than a macro one, it is crucial to prioritize PCSR over objective CSR measures. This approach aligns with the views of scholars such as Kim and Lee (2022), Li et al. (2020) and Ng et al. (2019).

The research results first confirm that employees’ PCSR significantly influences their innovation behavior. The higher the employees’ PCSR, the more innovation behavior they exhibit at work. This finding aligns with the research of Hur et al. (2018) and Li et al. (2020). This study considers that CSR improves relationships with various stakeholders and increases internal and external social capital (Blanco-Gonzalez et al. 2020), which can enhance employee innovation behavior (Zhao et al. 2022). On the other hand, CSR activities elevate corporate reputation (Ali et al. 2020; Javed et al. 2020), influencing employees’ behaviors and values (De Roeck and Farooq 2018; Van Dick et al. 2020). CSR activities can also improve the work environment (Mao et al. 2021), making employees more willing to actively explore and apply new technologies, processes or methods at work (De Roeck and Farooq 2018; Rongbin et al. 2022), which helps stimulate innovation behavior. Moreover, CSR programs often require close communication and collaboration among various departments and employees, fostering teamwork and collaborative innovation within the company (Li et al. 2020) and further encouraging employee innovation behavior.

Secondly, the findings of this study also validate the positive impact of employees’ PCSR on organizational commitment. This study posits that when organizations actively undertake CSR, employees become more closely linked with the company principles as they see the benefits of these efforts (Tian and Robertson 2019). CSR fosters the alignment of employee values with the organization, creating a strong emotional connection that enhances affective and normative commitment (Diatmono 2019). At the same time, CSR also helps to build social capital and promote corporate sustainable development (Blanco-Gonzalez et al. 2020; Barauskaite and Streimikiene 2021). It helps retain internal members and enhance employee loyalty (Cachón-Rodríguez et al. 2022), which will help enhance employees’ continuance commitment. Moreover, this study found that the impact of PCSR on continuance commitment is the most significant, which further demonstrates that a positive CSR experience can enhance employees’ willingness to continue serving the company.

Thirdly, this study confirms the positive impact of organizational commitment on employee innovation behavior, with normative commitment having a more significant influence on employee innovation behavior, reflecting that employees with a sense of obligation are more willing to innovate. Additionally, this study reveals the mediating roles of organizational commitment between employees’ PCSR and innovation behavior. In the existing literature, some scholars have confirmed that PCSR can increase organizational commitment (Kong et al. 2019; George et al. 2021; Tran et al. 2021; Silva et al. 2023; Li and Qu 2023); Organizational commitment can positively influence innovation behavior (Nazir et al. 2018; Fauziawati 2021; Chen and Liu 2022; Chtioui et al. 2023). Li and Qu (2023) also studied combining internal CSR with organizational commitment and innovation behavior. However, these scholars often view organizational commitment as a singular construct or analyze it only in terms of affective commitment, lacking exploration of specific dimensions of organizational commitment and failing to integrate the multiple mediating relationships between employees’ PCSR, affective commitment, normative commitment, continuance commitment and employee innovation behavior.

This study finds that affective commitment, normative commitment and continuance commitment all positively impact employee innovation behavior and simultaneously play multiple mediating roles between PCSR and innovation behavior. The impact of employees’ PCSR on their innovation behavior can be understood within the S-O-R theoretical framework, where organizational commitment acts as an internal psychological process that explains individuals’ perception of their environment and forms specific behaviors (Wu and Chen 2018; Ahmed and Tahir 2019; Lu et al. 2020), mediating between perception and behavior and linking the PCSR to employee innovation behavior. This study also reveals that while all three types of commitment play a partial mediating role, the contributions of different types of commitment to the mediating effects vary slightly. The mediating effects of continuance commitment are the most significant. The findings of this study further elucidate the critical mediating mechanisms through which PCSR translates into innovation behavior through employee organizational commitment. This research enriches and refines our theoretical understanding of the origins and influences of employee organizational commitment and innovation behavior, thereby augmenting the existing S-O-R literature.

Fourthly, this study, conducted within the context of Chinese organizations, provides valuable contributions to the literature on the impact of employees’ PCSR on their psychology and work behavior in Eastern cultural settings. Additionally, AI enterprises are marked by innovation (Dong et al. 2020). The selection of Shenzhen—a model city for AI industry development in China (Shenzhen Artificial Intelligence Industry Association 2024)—as the focus of this study provides significant representativeness. Using employees from Shenzhen AI enterprises as subjects for examining innovation behavior offers robust support for a deeper understanding of the formation and enhancement of innovation capabilities among contemporary Chinese firms.

5.2. Managerial Implications

These study results have managerial implications and can offer business managers valuable recommendations. First, this study illustrates how employees’ attitudes and behaviors are influenced by their PCSR. The importance of studying PCSR and encouraging managers to consider employees’ perspectives on CSR activities is underscored by the fact that people’s views on CSR vary. Currently, many companies regularly publish CSR reports, using the disclosure of CSR information to make their management more transparent (Escamilla-Solano et al. 2024). Nevertheless, organizations may employ more methodologies to enhance their employees’ PCSR. For instance, employees’ PCSR can be enhanced by publishing information about CSR on websites, integrating CSR into training materials, routinely announcing CSR activities and encouraging employees to participate in these programs.

Secondly, employees’ PCSR still comes from objective CSR activities. Therefore, if business managers want to enhance employees’ organizational commitment and innovative behavior through PCSR, they still need to pay attention to CSR activities. Consequently, business managers should raise their level of CSR awareness, take on their fair share of duties to all parties involved and cultivate a stellar reputation and corporate image. Moreover, management, day-to-day operations and business development goals should all actively include CSR. Business managers need to understand the strategic significance of carrying out CSR. The company’s board of directors must set up a CSR group to standardize supervision and evaluate implementation when necessary. Business managers should end short-sighted behavior, position the company as the main body of CSR and oppose the paradigm of decision-making that prioritizes short-term financial gain above long-term CSR.

This study confirmed the positive relationship between PCSR, organizational commitment and employee innovation behavior. This conclusion can also encourage business managers to stimulate employees’ organizational commitment while fulfilling CSR to convey positive mediating effects. Understanding the role of different types of organizational commitments is essential for maximizing the promotion of innovation behavior. Considering that the mediating effect of continuance commitment is the most significant, it also shows that if employees can serve the company for a long time, it will be more effective in corporate innovation. To achieve this, business managers should pay special attention to employees’ psychological well-being, closely integrate social responsibility fulfillment with organizational commitment and amplifying the positive impact of PCSR on employee innovation behavior through strengthening organizational commitment. Specifically, in strengthening affective commitment, companies should enhance care and trust for employees to foster emotional bonds between employees and the organization. Long-term talent strategies, better work conditions and fair reward programs should be implemented to enhance the company’s reputation and foster employee identification with the company, thereby increasing employee continuance commitment. As for enhancing normative commitment, efforts should be made to enhance employees’ sense of belonging to the company, align their values with organizational values, cultivate a sense of responsibility and promote innovative behavior.

6. Conclusions

Through empirical testing, this study demonstrates that PCSR significantly improves employee innovation behavior and affective, normative and continuance commitments. PCSR has a stronger impact on continuance commitment. Affective, normative and continuance commitments positively impact employee innovation behavior; however, normative commitments have a stronger influence than affective and continuance commitments. Furthermore, affective, normative and continuance commitments mediate the relationship between employee innovation behavior and PCSR. The mediating effects of continuance commitment are the most significant, indicating that the impact of PCSR not only directly influences organizational commitment but also indirectly affects innovation behavior through the mediation of organizational commitment.

This study’s findings improve CSR research at the micro level and fill in existing gaps in the literature by extending research on the multiple mediation mechanisms between employees’ PCSR and innovation behavior. It also provides a broader perspective for examining the intricate relationships between employee attitudes and behaviors and PCSR. In addition, in practice, it provides a new perspective for business managers to find new motivations and channels for employee organizational commitment and innovation behavior, which helps to enhance corporate competitiveness and sustainable development.

Some limitations of this study include its primarily cross-sectional research approach and the inability to conduct a comprehensive sampling survey of the entire population due to financial and resource constraints. Future research may utilize objective indicators and longitudinal methods and consider conducting larger sample surveys in different countries, regions and among various types of enterprises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft: H.H. and C.S. Data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software, validation, writing—review and editing: H.H. Resource supervision: C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and thus cannot be publicly accessed. However, the data can be provided by the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the third party.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of the Doctor of Philosophy in Management program at the College of Interdisciplinary Studies (CBIS) at Rajamangala University of Technology Tawan-ok in Thailand. The researchers would like to thank all the cited experts who have contributed to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The present study has no conflicts of interest with any organization or individual.

Appendix A

The following are the specific contents of each variable measurement scale:

Employee Innovation Behavior (EB) Scale

EB1. I will actively seek to apply new technologies, procedures, or methods.

EB2. I cultivate insightful perspectives and innovative concepts.

EB3. I engage frequently in communication to explain and elaborate on my fresh ideas.

EB4. I will find ways to obtain the necessary resources to realize my new ideas or creativity.

EB5. I diligently formulate suitable schemes and initiatives to execute innovative ideas.

EB6. I am an innovative and creative person.

PCSR Scale

PCSR1. Our company participates in activities which aim to protect and improve the quality of the natural environment.

PCSR2. Our company strives for sustainable development and invests in fostering a better future for generations to come.

PCSR3. Our company implements special programs to minimize our detrimental impact on the natural environment.

PCSR4. Our company’s managerial decisions related to the employees are usually fair.

PCSR5. Our company supports non-governmental organizations operating in areas of need.

PCSR6. Our company contributes to endeavors and projects that promote societal well-being.

PCSR7. Our company encourages its employees to participate in voluntary activities.

PCSR8. Our company respects consumer rights, surpassing mere legal requirements.

PCSR9. Our company provides customers with thorough and accurate information about its products.

PCSR10. Customer satisfaction holds significant importance in our company’s operations.

PCSR11. Our company maintains regular and consistent tax payments.

PCSR12. Our company complies with legal regulations completely and promptly.

Organizational Commitment Scale

Affective Commitment (AC)

AC1. I would happily spend the rest of my career with this company.

AC2. I feel as if my company’s problems are my own.

AC3. I feel a strong sense of belonging to my company.

AC4. I feel emotionally bonded with my company.

AC5. I feel like part of the family at my company.

AC6. This company has a great deal of personal meaning for me.

Normative Commitment (NC)

NC1. I feel the obligation to remain with my current employer.

NC2. Even if it were to my advantage, leaving the company now would be wrong.

NC3.I would feel guilty if l left this company now.

NC4. This company deserves my loyalty.

NC5. I would not leave my company right now because I feel obligated to the people in it.

NC6. I owe a great deal to my company.

Continuance Commitment (CC)

CC1. Currently, staying with my company is a matter of necessity as much as desire.

CC2. It would be hard for me to leave my company right now, even if l wanted to.

CC3. Too much of my life would be disrupted if I decided to leave my company now.

CC4. I have too few options to consider leaving this company.

CC5. I might consider working elsewhere if I have not put much into this company.

CC6. One of the few negative consequences of leaving this company is the need for more available alternatives.

References

- Ahmad, Naveed, Zia Ullah, Muhammad Zulqarnain Arshad, Hafiz waqas Kamran, Miklas Scholz, and Heesup Han. 2021. Relationship between corporate social responsibility at the micro-level and environmental performance: The mediating role of employee pro-environmental behavior and the moderating role of gender. Sustainable Production and Consumption 27: 1138–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Mansoora, Sun Zehou, Syed Ali Raza, Muhammad Asif Qureshi, and Sara Qamar Yousufi. 2020. Impact of CSR and environmental triggers on employee green behavior: The mediating effect of employee well-being. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 2225–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Nurulatika, and Nor Suziwana Tahir. 2019. Employees’ perception on corporate social responsibility practices and affective commitment. Journal of Accounting Research, Organization and Economics 2: 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Jee Ahe, and Soobin Seo. 2018. Consumer responses to interactive restaurant self-service technology (IRSST): The role of gadget-loving propensity. International Journal of Hospitality Management 74: 109–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Sidhoum, Amer, and Teresa Serra. 2018. Corporate Sustainable Development. Revisiting the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility Dimensions. Sustainable Development 26: 365–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhumoudi, Ranya Saeed, Sanjay Kumar Singh, and Syed Zamberi Ahmad. 2023. Perceived corporate social responsibility and innovative work behaviour: The role of passion at work. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 31: 2239–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Hafiz Yasir, Rizwan Qaiser Danish, and Muhammad Asrar-ul-Haq. 2020. How corporate social responsibility boosts firm financial performance: The mediating role of corporate image and customer satisfaction. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 166–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenal, Alberto, Cristina Armuña, Claudio Feijoo, Sergio Ramos, Zimu Xu, and Ana Moreno. 2020. Innovation ecosystems theory revisited: The case of artificial intelligence in China. Telecommunications Policy 44: 101960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiq, Saman, Hassan Rasool, and Shahid Iqbal. 2017. The impact of supportive work environment, trust, and self-efficacy on organizational learning and its effectiveness: A stimulus-organism response approach. Business Economic Review 9: 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barauskaite, Gerda, and Dalia Streimikiene. 2021. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance of companies: The puzzle of concepts, definitions and assessment methods. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 28: 278–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, Enrique, Luisa Andreu, Carmen Perez, and Carla Ruiz. 2020. Brand love is all around: Loyalty behaviour, active and passive social media users. Current Issues in Tourism 23: 1613–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Gonzalez, Alicia, Francisco Diéz-Martín, Gabriel Cachón-Rodríguez, and Camilo Prado-Román. 2020. Contribution of social responsibility to the work involvement of employees. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 2588–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachón-Rodríguez, Gabriel, Alicia Blanco-González, Camilo Prado-Román, and Cristina Del-Castillo Feito. 2022. How sustainable human resources management helps in the evaluation and planning of employee loyalty and retention: Can social capital make a difference? Evaluation and Program Planning 95: 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Viet Quoc. 2023. How does corporate social responsibility affect innovative work behaviour. Global Business and Finance Review 28: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie B. 1979. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. The Academy of Management Review 4: 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chao, and Xinmei Liu. 2022. Relative team-member exchange, affective organizational commitment and innovative behavior: The moderating role of team-member exchange differentiation. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 948578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Jiali, and Aiqing Zhang. 2023. Exploring How and When Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility Impacts Employees’ Green Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Creative Self-Efficacy and Environmental Commitment. Sustainability 16: 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Information Security Standardization Technical Committee. 2019. Artificial Intelligence Security Standardization White Paper (2019 Edition). Available online: https://www.cesi.cn/images/editor/20191101/20191101115151443.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Cho, Yoon Jik, and Hyun Jin Song. 2021. How to facilitate innovative behavior and organizational citizenship behavior: Evidence from public employees in Korea. Public Personnel Management 50: 509–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Suk Bong, Nicole Cundiff, Kihwan Kim, and Saja Nassar Akhatib. 2018. The Effect of Work-Family Conflict and Job Insecurity on Innovative Behaviour of Korean Workers: The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment dan Job Satisfaction. International Journal Od Innovation Management 22: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chtioui, Rachèd, Sarra Berraies, and Amal Dhaou. 2023. Perceived corporate social responsibility and knowledge sharing: Mediating roles of employees’ eudaimonic and hedonic well-being. Social Responsibility Journal 19: 549–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, Kenneth, and Omer Farooq. 2018. Corporate Social Responsibility and Ethical Leadership: Investigating Their Interactive Effect on Employees’ Socially Responsible Behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics 151: 923–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diatmono, Prastiyo. 2019. Effect Of Behavior Leadership and Job Satisfaction to Organization Commitment Through Employee Trust as Variable Mediating in Pt. Bram. Business and Entrepreneurial Review 19: 107–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Yuanyuan, Zepeng Wei, Tiansen Liu, and Xinpeng Xing. 2020. The impact of R & D intensity on the innovation performance of artificial intelligence enterprises-based on the moderating effect of patent portfolio. Sustainability 13: 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Akremi, Assâad, Jean-Pascal Gond, Valérie Swaen, Kenneth De Roeck, and Jacques Igalens. 2018. How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. Journal of Management 44: 619–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Solano, Sandra, Antonio Fernández-Portillo, Mari Cruz Sánchez-Escobedo, and Carmen Orden-Cruz. 2024. Corporate social responsibility disclosure: Mediating effects of the economic dimension on firm performance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 31: 709–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Solano, Sandra, Jessica Paule-Vianez, Paola Plaza Casado, and Susana Díaz-Iglesias. 2023. Scientific evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility. A bibliometric analysis with mapping analysis tools. Anais Da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias 95: e20210215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauziawati, Dian. 2021. The Effect of Job Insecurity on Innovative Work Behavior through Organizational Commitment in UFO Elektronika Employees. Journal of Business and Management Review 2: 401–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, Ahmed Shahriar, Michael Polonsky, and David Hugh Blore Bednall. 2021. Internal communication and the development of customer-oriented behavior among frontline employees. European Journal of Marketing 55: 2344–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Yudi, Charbel Jose Chiappetta Jabbour, and Wen Xin Wah. 2019. Pursuing green growth in technology firms through the connections between environmental innovation and sustainable business performance: Does service capability matter? Resources, Conservation and Recycling 141: 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, Caroline, and Aleksandra Kacperczyk. 2019. Corporate social responsibility as a defense against knowledge spillovers: Evidence from the inevitable disclosure doctrine. Strategic Management Journal 40: 1243–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Nimmy A., Nimitha Aboobaker, and Manoj Edward. 2020. Corporate social responsibility and organizational commitment: Effects of CSR attitude, organizational trust and identification. Society and Business Review 15: 255–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Nimmy A., Nimitha Aboobaker, and Manoj Edward. 2021. Corporate social responsibility, organizational trust and commitment: A moderated mediation model. Personnel Review 50: 1093–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasempour Ganji, Seyedeh Fatemeh, Fariborz Rahimnia, Mohammad Reza Ahanchian, and Jawad Syed. 2021. Analyzing the impact of diversity management on innovative behaviors through employee engagement and affective commitment. Iranian Journal of Management Studies 14: 649–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, Jean-Pascal, Assâad El Akremi, Valérie Swaen, and Nishat Babu. 2017. The psychological micro foundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior 38: 225–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Yong. 2024. PCT International Patent Applications Achieve 20 Consecutive Championships. Shenzhen Special Zone Daily. April 26. Available online: https://sztqb.sznews.com/MB/content/202404/26/content_3203902.html (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1998. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to under parameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods 3: 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Yushan, Shuqin Wei, and Tyson Ang. 2022. The role of customer perceived ethicality in explaining the impact of incivility among employees on customer unethical behavior and customer citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Ethics 1782: 519–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Won-Moo, Tae-Won Moon, and Sung-Hoon Ko. 2018. How employees’ perceptions of CSR increase employee creativity: Mediating mechanisms of compassion at work intrinsic motivation. Journal of Business Ethics 153: 629–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Amjad, Khawaja Fawad Latif, and Muhammad Shakil Ahmad. 2020. Servant leadership and employee innovative behaviour: Exploring psychological pathways. Leadership and Organization Development Journal 41: 813–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, Muzhar, Muhammad Amir Rashid, Ghulam Hussain, and Hafiz Yasir Ali. 2020. The effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and firm financial performance: Moderating role of responsible leadership. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 1395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleel, Muhammad, Shankar Chelliah, Sana Rauf, and Muhammad Jamil. 2017. Impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on attitudes and behaviors of pharmacists working in MNCs. Humanomics 33: 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Muhammad Aamir Shafique, Jianguo Du, Farooq Anwar, Hira Salah ud Din Khan, Fakhar Shahzad, and Sikandar Ali Qalati. 2021. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Reciprocity Between Employee Perception, Perceived External Prestige, and Employees’ Emotional Labor. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 14: 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Hyunok, and Myeongju Lee. 2022. Employee perception of corporate social responsibility authenticity: A multilevel approach. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 948363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Haiyan, Naipeng Bu, Yue Yuan, Kangping Wang, and Young Hee Ro. 2019. Sustainability of Hotel, How Does Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility Influence Employees’ Behaviors? Sustainability 11: 7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, Robert V., and Daryle W. Morgan. 1970. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement 30: 607–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Kibum, and Taesung Kim. 2020. An integrative literature review of employee engagement and innovative behavior: Revisiting the JD-R model. Human Resource Management Review 30: 100704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laesser, Christian, Jieqing Luo, and Pietro Beritelli. 2019. The SOMOAR operationalization: A holistic concept to travel decision modelling. Tourism Review 12: 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Xiyu, and Han Wen. 2020. Chatbot usage in restaurant takeout orders: A comparison study of three ordering methods. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 45: 377–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Xi Y., Bryan Torres, and Alei Fan. 2021. Do kiosks outperform cashiers? An SOR framework of restaurant ordering experiences. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology 12: 580–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jiaxiang, and Xiaoting Qu. 2023. Research on the Relationship between Internal Corporate Social Responsibility, Organizational Commitment, and Employee Innovative Behavior. Advances in Economics and Management Research 5: 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Li, Xinwen Bai, and Yiyong Zhou. 2023. A Social Resources Perspective of Employee Innovative Behavior and Outcomes: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 15: 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Suyu. 2024. The national standard for artificial intelligence has a “depth content” of 60%. Shenzhen Special Zone Daily. April 11. Available online: https://sztqb.sznews.com/MB/content/202404/11/content_3197835.html (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Li, Yibin, Guiqing Zhang, Tungju Wu, and Chilu Peng. 2020. Employee’s corporate social responsibility perception and sustained innovative behavior: Based on the psychological identity of employees. Sustainability 12: 8604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loan, Le Thi Minh. 2020. The influence of organizational commitment on employees’ job performance: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Management Science Letters 10: 3307–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Jintao, Licheng Ren, Chong Zhang, Chunyan Wang, Rizwan R. Ahmed, and Justas Streimikis. 2020. Corporate social responsibility and employee behavior: Evidence from mediation and moderation analysis. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 1719–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Yan, Jie He, Alastair M. Morrison, and Andres J. Coca-Stefaniak. 2021. Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis: From the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Current Issues in Tourism 24: 2716–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, Albert, and James A. Russell. 1974. An Approach to Environmental Psychology. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, John P., and Natalie J. Allen. 1991. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review 1: 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John P., Natalie J. Allen, and Catherine A. Smith. 1993. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 538–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, Richard T., Richard M. Steers, and Lyman W. Porter. 1979. The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior 14: 224–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, Sajjad, Wang Qun, Li Hui, and Amina Shafi. 2018. Influence of social exchange relationships on affective commitment and innovative behavior: Role of perceived organizational support. Sustainability 10: 4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Thomas W. H., Kai Chi Yam, and Herman Aguinis. 2019. Employee perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Effects on pride, embeddedness, and turnover. Personnel Psychology 72: 107–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Viet, Bang, Cong Thanh Tran, and Hoa Thi Kim Ngo. 2024. Corporate social responsibility and behavioral intentions in an emerging market: The mediating roles of green brand image and green trust. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption 12: 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, Nurlan. 2020. Do board sustainability committees contribute to corporate environmental and social performance? The mediating role of corporate social responsibility strategy. Business Strategy and the Environment Environ 29: 140–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, Shailesh, Hari Govind Mishra, and Shagun Chib. 2021. Psychological impact of COVID-19 crises on students through the lens of Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model. Children and Youth Services Review 120: 105783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., and Dennis W. Organ. 1986. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. Journal of Management 12: 531–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujianto, Wahyu Eko, and Lailatul Musyaffaah. 2023. Organizational Justice to Employee Innovative Work Behavior: Mediation Effect of Learning Capacity and Moderation Effect of Blue Ocean Leadership. GREENOMIKA 5: 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylypenko, H. M., Yu I. Pylypenko, Yu V. Dubiei, L. G. Solianyk, Yu M. Pazynich, V. Buketov, and M. Magdziarczyk. 2023. Social capital as a factor of innovative development. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 9: 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, Ulf Henning, Vikrant Shirodkar, and Namita Shete. 2021. Firm-level indicators of instrumental and political CSR processes–A multiple case study. European Management Journal 39: 279–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongbin, Ruan, Chen Wan, and Zhu Zuping. 2022. Research on the relationship between environmental corporate social responsibility and green innovative behavior: The moderating effect of moral identity. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29: 52189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, Susanne G., and Reginald A. Bruce. 1994. Determinants of Innovative Behavior: A Path Model of Individual Innovation in the Workplace. Academy of Management Journal 37: 580–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Sahiba, Gyan Prakash, Anil Kumar, Eswara Krishna Mussada, Jiju Antony, and Sunil Luthra. 2021. Analysing the relationship of adaption of green culture, innovation, green performance for achieving sustainability: Mediating role of employee commitment. Journal of Cleaner Production 303: 127039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenzhen Artificial Intelligence Industry Association. 2024. 2024 White Paper on the Development of Artificial Intelligence. Available online: https://www.saiia.org.cn/index.php/7-2/ (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Silva, Pedro, Antonio Carrizo Moreira, and Jorge Mota. 2023. Employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility and performance: The mediating roles of job satisfaction, organizational commitment and organizational trust. Journal of Strategy and Management 16: 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, Andelka, Isidora Milosevic, Sanela Arsic, Snezana Urosevic, and Ivan Mihajlovic. 2020. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Determinant of Employee Loyalty and Business Performance. Journal of Competitiveness 12: 149–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Lujun, and Scott R. Swanson. 2019. Perceived corporate social responsibility’s impact on the well-being and supportive green behaviors of hotel employees: The mediating role of the employee-corporate relationship. Tourism Management 72: 437–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Zhenya, Merrill Warkentin, and Wu Le. 2019. Understanding employees’ energy saving behavior from the perspective of stimulus-organism-responses. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 140: 216–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Christopher Glen, Rae Seon Kim, Ariel M. Aloe, and Betsy Jane Becker. 2017. Extracting the variance inflation factor and other multicollinearity diagnostics from typical regression results. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 39: 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Qing, and Jennifer L. Robertson. 2019. How and when does perceived CSR affect employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior? Journal of Business Ethics 155: 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Zelin, Liya Zhu, Ning Zhang, Lisher Livuza, and Nan Zhou. 2019. Employees’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility and creativity: Employee engagement as a mediator. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 47: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Trang Thi, Tien Thuy Nguyen, Duyen Nguyen Thien Ngo, and Tung Anh Tran. 2021. Mediation of employee job satisfaction on the relationship between internal corporate social responsibility and affective commitment. Management Science Letters 11: 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, Duygu. 2009. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. Journal of Business Ethics 89: 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dick, Rolf, Jonathan R. Crawshaw, Sandra Karpf, Sebastian C. Schuh, and Xinan Zhang. 2020. Identity, importance, and their roles in how corporate social responsibility affects workplace attitudes and behavior. Journal of Business and Psychology 35: 159–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Chi-Min, and Tso-Jen Chen. 2018. Collective psychological capital: Linking shared leadership, organizational commitment, and creativity. International Journal of Hospitality Management 74: 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Tung-Ju, Kuo-Shu Yuan, David C. Yen, and Ting Xu. 2019. Building up resources in the relationship between work–family conflict and burnout among firefighters: Moderators of guanxi and emotion regulation strategies. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 28: 430–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Weiwei, Li Yu, Haiyan Li, and Tianyi Zhang. 2022. Perceived environmental corporate social responsibility and employees’ innovative behavior: A stimulus–organism–response perspective. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 777657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Fengzeng, and Ying Wang. 2020. Enhancing employee innovation through customer engagement: The role of customer interactivity, employee affect, and motivations. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 44: 351–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Changqin, Huimin Ma, Yeming Gong, Qian Chen, and Yajun Zhang. 2021. Environmental CSR and environmental citizenship behavior: The role of employees’ environmental passion and empathy. Journal of Cleaner Production 320: 128751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Yutian, Zhongfeng Hu, Jiawei Li, Youhan Wang, and Mingli Xu. 2022. The Effect of Organizational Innovation Climate on Employee Innovative Behavior: The Role of Psychological Ownership and Task Interdependence. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 856407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaman, Umer, and Raja Danish Nadeem. 2019. Linking corporate social responsibility (CSR) and affective organizational commitment: Role of CSR strategic importance and organizational identification. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences 13: 704–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Xiaoyang, Changjun Yi, and Chusheng Chen. 2022. How to stimulate employees’ innovative behavior: Internal social capital, workplace friendship and innovative identity. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1000332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Bing, Suwanna Kowatthanakul, and Punnaluck Satanasavapak. 2020. Generation Y consumer online repurchase intention in Bangkok. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 48: 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).