Abstract

The board of directors appoints the audit committee to assess the financial performance of the firm. The audit committee uses reports provided by audit firms, such as Form 10Ks, and annual reports to assess firm financial performance. The degree of audit oversight quality is a governance measure, which, if effective, may reduce firm risk. This study measures the effect of three measures of audit oversight quality on insolvency risk, systematic risk, and volatility of return on assets for a sample of U.S. pharmaceutical firms and energy firms from 2010 to 2022. All measures of audit oversight quality reduced firm risk, with the first measure reducing both systematic risk and volatility of return on assets, the second measure reducing systematic risk, and the third measure reducing volatility of return on assets. As institutional ownership is also a governance measure, we tested whether its joint effect with audit oversight quality reduced firm risk. This hypothesis was supported for all three measures of audit oversight quality for systematic risk and for the third audit oversight quality measure for volatility of assets. Robustness was established by replicating the regressions with an alternate governance measure, which yielded similar results. Endogeneity of all audit oversight quality measures was absent due to lack of significance of leverage, firm size, equity multiplier, and firm value in reducing risk through their effect on audit oversight quality.

1. Introduction

Corporate governance practices are centered on limiting shareholder expropriation by management. Practices include an active board, elimination of CEO–board chair duality, independent directors, and the presence of large shareholders on the board (Chen et al. 2011). These measures restrict agency conflicts between management and shareholders. The conflicts arise from management placing its own interests above that of shareholder wealth maximization. Jensen and Meckling (1976)’s seminal paper showed that agency conflicts resulted in misuse of cash and investment in unprofitable projects that confer visibility to attention-seeking managers. Agency conflicts may be mitigated by effective monitoring of management. The board’s audit committee may provide such monitoring by generating quality financial reports and identifying material misstatements (Ishak 2016). Specifically, accounting transactions must conform to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) (Pomeranz 1997), and quality financial reports must be created (Wolnizer 1995). Elmarzouky et al. (2023) provided a detailed review of audit oversight quality. Audit committees use audit quality reports of financial irregularities provided by audit firms to identify critical audit matters (KAMs). Firms using KAMs as input into decision making have observed reduced loan spreads (Porumb et al. 2021) and reduced volatility of earnings (Bens et al. 2019).

Institutional theory (Meyer and Rowan 1977) maintains that firms must adhere to professional standards. Through its monitoring of management, audit committees correct inaccurate financial statements, such as earnings misstatements, expense, and accrual inaccuracies, in accordance with industry standards. This audit oversight may assist firms in making prudent financial decisions as actual earnings, expenses, and accruals than excessively optimistic measures. Resource dependence theory (Hillman and Dalziel 2003) suggests that the links among corporate departments, such as sales, production, and accounting, are strengthened as audit committees provide accurate and timely information to other departments for the setting of realistic goals.

While audit committee oversight has been established in the literature as effective in improving firm financial performance (see Ishak 2016 for a review), there is a paucity of the literature regarding the effect of audit committee oversight on firm risk. Conceptually, risks are uncertainties that can result in loss of market share, sales, net income, and firm value. Accounting scandals may drive away customers. Failure to comply with ESG regulations will result in fines and lawsuits, leading to reputational damage. Vendors do not wish to do business with firms that are scandal-prone. Regulators blacklist firms with numerous warnings and sanctions.

We conjecture that effective audit committee oversight will result in the reduction of firm risk. Audit oversight consists of the monitoring of management and the provision of quality financial reports. Risky ventures that appeal to management may be curtailed by audit reports showing the lack of funds for such projects. Excessive expenses and excessive accruals will send the signal to the board that management is spending excessively.

The purpose of this paper is to employ three measures of audit oversight quality to measure the effect of audit oversight on firm risk. Risk is measured as insolvency risk, systematic risk, and volatility of return on assets. Our objective is to shed light on the power of a governance measure to assist firms in reducing the excessive risk that could lead to insolvency, lack of investor confidence, and adverse relationships with stakeholders. If we find that audit oversight reduces insolvency risk, audit committees will provide management with an early warning signal before regulatory sanctions on the firm. If we find that audit oversight reduces systematic risk, it will signal to investors that the firm is less risky, and a favorable venue for investment. If audit oversight reduces the ROA volatility, internal and external stakeholders will be able to adjust their forecasts more accurately.

One type of risk is insolvency risk. The Altman Z, a common measure of bankruptcy risk, is based on the financial statement measures of working capital, retained earnings, operating income, market value, and sales. As the audit committee is charged with correcting material misstatements in financial statements, it is in a position to ensure that accurate measures of these balance sheet accounts are presented. For example, an increase in accruals will increase current liabilities, depressing working capital and operating income. As working capital and operating income are used to compute the Altman Z, reduced working capital will reduce Z, highlighting the risk of insolvency.

Beta is a measure of systematic risk. It is the risk that is inherent to the firm that cannot be reduced by diversification (Sharpe 1964). It is the correlation of security prices with market prices. Beta risk will increase in firms that have uncertainties that are not present in the typical firm. These uncertainties could include a sudden loss of customers due to increased competition or regulatory pressure. The loss of customers will be reflected in stock prices varying from the norm, or an increase in the risk of the firm as shown by heightened beta values. Audit committee reports that comprehend the firm’s ability to manage risks (Ishak 2016) will include sales reports showing fewer customers, while correcting for misstatements of profits from unrealistic sales forecasts.

The volatility of return on assets is a balance sheet measure of firm risk. Return on assets is the net income generated from each unit of investment in the firm’s assets. Variations in return on assets stem from variations in net income or profitability. These variations may originate from weak sales or unforeseen increases in expenses. Accurate financial reporting of transactions as stated in audit quality reports will reveal reductions in sales and increases in expenses. Effective audit committee oversight will draw the board’s attention to these lapses, initiating corrective action.

We created three measures of audit oversight quality. The first measure provides the total frequency with which the words ‘audit committee’ are mentioned in annual reports, Form 10Ks, and Form 10Qs. We contend that the greater frequency of mentions of ‘audit committee’ in firm reports suggests an active audit committee that is engaged in providing the financial information needed for effective decision making. The second measure is the total number of long paragraphs (>30 words) in the annual reports, Form 10Ks, and Form 10Qs that contain the words ‘audit committee’. This suggests audit committee engagement in key decisions, i.e., decisions of importance that are described in detail. The third measure is the total number of paragraphs in firm reports with the words ‘audit committee’. This suggests audit committee engagement in decisions of moderate to high importance, as entire paragraphs are devoted to describing these decisions. We also test the joint effect of audit oversight quality and institutional ownership on firm risk. We posit that, as institutional investors such as pension funds have vast resources, they have access to investment talent that will select securities from firms with strong governance that reduce firm risk. Therefore, institutional ownership is a corporate governance measure that reinforces the governance capabilities of audit oversight quality.

We advance knowledge in four ways. First, the measure of audit oversight quality based on the frequency with which the word ‘audit committee’ is mentioned in firm reports is unique. We can locate only one other study in which one of these measures was used (Abraham et al. 2024). In that study, the first measure of total frequency of mention of audit committees was used. The other two measures are used in this study for the very first time. Further, Abraham et al. (2024) measured audit oversight quality on firm performance not firm risk. Second, there is a paucity of research on the effectiveness of audit committee oversight on firm risk. As audit committee review of financial reports occurs on an ongoing basis, audit committee oversight provides a stream of accurate financial information that can serve as an early warning system to firms facing uncertain sales. Firms can then take corrective action before a sharp deterioration in financial performance that could result in insolvency. During economic downturns, audit oversight can highlight vulnerabilities in sales, markets, and losses of customers by measuring systematic risk and volatility of return on assets. Third, we add audit committee effectiveness on reducing risk to existing studies that have found that audit committee composition (Ferreira 2008), audit committee characteristics (Al-Ahdal and Hashim 2022; Ayman 2022), and ownership concentration (Shetnawi et al. 2021) improve firm financial performance. Unlike financial performance, risk is a negative outcome. Enhancing financial performance through audit oversight suggests that effective governance enhances a positive outcome but does not safeguard the firm from negative consequences such as insolvency. Risk reduction safeguards the firm from insolvency, arguably rendering audit oversight’s effect on risk reduction to be more consequential than its enhancement of firm performance. Fourth, we add to the literature on the governance effects of institutional ownership on audit committee activity. The existing literature has found that institutional ownership increases audit committee independence (Ali and Meah 2021), increases women’s contribution to intellectual capital efficiency on audit committees increases audit committee engagement by increasing the frequency of meetings (Sharma et al. 2009), and reduces material control weaknesses (Tang and Xu 2007). The positive effects of institutional ownership on corporate governance may be attributed to demands by institutional investors for greater management accountability. This additional demand for accountability may be met by the monitoring capability of audit oversight, which may expose management’s excessive risk taking. Managers may respond by restricting such risk taking. This study converts this conceptual sequence into measures of the joint effect of institutional ownership and audit oversight on firm risk taking.

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Agency Theory as the Basis for Audit Oversight Quality

Agency theory was set forth by Jensen and Meckling (1976), who posited that managers as agents of shareholders (owners) frequently do not align themselves with the goal of shareholder wealth maximization. Managers may invest in low-NPV projects designed to draw attention to themselves, while failing to meet the profit goals of the firm. For example, overseas expansion may be ill-advised due to high risk of the proposed foreign location, uncertainty about repatriation of profits, and limited availability of productive labor. Yet, management may eagerly pursue this project as it increases its visibility, with concomitant rewards such as wage increases, bonuses, and promotions. Abraham et al. (2024) detailed the benefit of audit committee oversight in limiting agency costs. Auditors are an independent third party in the assessment of a firm’s financial performance. Audit committees that exercise effective oversight will carefully select auditors who provide quality financial reports that highlight material misstatements and critical audit matters. The increased transparency and disclosure will highlight unusual expenses and excessive accruals that arise from management undertaking unprofitable projects that serve their own interests (Halim 2013). Elmarzouky et al. (2022) interacted critical audit matters with the corporate governance mechanism of independent directors, finding an increase in firm financial performance. The joint effect of key audit revelations in an environment that promoted objective assessment of managers by external directors effectively eliminated agency conflicts.

However, some audit committee activities cannot be explained in terms of their effect on agency costs. The results of Stroh et al. (1996) questioned agency theory’s ability to predict compensation strategy for middle-level managers in the high-risk situation. In addition, Francis and Wilson (1988) investigated whether there is a positive relationship between a firm’s agency costs and its demand for a quality-differentiated audit. Kalbers and Fogarty (1998) showed that audit committee activities and effectiveness are not explained by agency theory variables. The authors revealed that results are coherent with the assumption of institutional theory that organizations’ publicly observable structures and activities are only loosely connected to their inner workings. Dey (2008) revealed that firms with greater agency conflicts have better governance mechanisms in place, specifically those related to the board, audit committee, and auditor. This author also showed that the composition and functioning of the board, the independence of the auditor, and the equity-based compensation of directors are significantly related to firm performance (but mainly for firms with high agency conflicts).

2.2. Institutional Theory and Audit Oversight

Institutional theory posits that, within an organization, there are certain norms and social rules that must be followed for organizational survival that go beyond performance and profit. The compliance with these rules confers legitimacy, stability, and access to resources (Meyer and Rowan 1977). These rules may be coercive isomorphism demanding mandatory compliance, normative isomorphism with compliance with professional norms, and mimetic isomorphism or copying processes with proven effectiveness used by other entities. Arena and Azzone (2009) and Alzeban (2015) noted that audit committees could achieve normative isomorphism by monitoring the organization’s ability to achieve professional norms. Given that auditing is an externally regulated function, audit committees can ensure that the reports generated by auditing firms that are used in firm decision making adhere to professional standards in their ability to accurately record revenue, expenses, and cash flows to prevent earnings management, misstatement of accounts, and padding accruals to hide unauthorized expenses. In a recent study, Vadasi et al. (2020) found that the contribution of audit committees to corporate governance was significantly influenced by their ability to comply with internal auditing standards and employ individuals with professional qualifications. In separate studies, Al-Twaijry et al. (2003) and Abolmohammadi (2009) found that the establishment of professional identity led to homogeneity in organizational practices. It follows that audit committees facilitate such establishments of professional identity, leading to professional standards of compliance for managers. In the context of firm risk, audit committees that require professional expertise and compliance with professional standards will be vigilant in uncovering financial irregularities dictated by the requirements of auditing standards. The identification of these aberrations can result in the corrective action needed to reduce firm risk.

2.3. Resource Dependency Theory and Audit Oversight

Resource dependency theory views the firm as consisting of a mass of entities that share resources with each other. Marketing departments work with production to identify customer preferences that are designed into products. Accounting departments employ economists to monitor regulatory developments. Vendors establish relationships with both accounting departments for timely payment and production to determine inventory levels. Audit committees facilitate these relationships by giving vendors accounts payable figures, giving marketers collections figures to determine credit policy, and managers earnings figures to assess firm performance. Therefore, audit committees draw on the resources of multiple entities from different disciplines. Nelson and Devi (2013) found that the financial expertise of audit committee members was insufficient in improving earnings quality. Upon measuring the contribution of two non-financial experts to the audit committee, the improvement in earnings quality was significantly enhanced. They concluded that resource dependency theory could explain audit committee performance in situations in which committee members broad knowledge and expertise linked resources among organizational functions. It follows that broad non-financial knowledge coupled with finance knowledge could improve the quality of financial reporting. If accounting and finance experts on the audit committee present accurate earnings figures, their nonfinancial peers could pass on that information to managers to compel them to reduce expenses, hire talent, or promote new products to increase revenue. These actions would reduce firm risk.

2.4. The Literature on Audit Oversight and Firm Risk Taking

Auditors submit a going concern qualification if they surmise that insolvency risk is so high that the firm may not exist as a going concern into the future. Huffman et al. (2023) attempted to uncover the success of going-concern qualifications in predicting insolvency. Both Type 1 error and Type 2 errors were found in the literature. They observed that Type 1 errors resulted in 80–90 percent of the cases, wherein firms that received going-concern qualifications were in business a year later. On the other hand, Geiger and Raghunandan (2002) observed Type 2 errors, whereby 45% of firms that filed for bankruptcy failed to receive a going-concern qualification. We surmise that going-concern qualifications have had limited success in predicting insolvency. Yet, Huffman et al. (2023) observed that liquidity shortages contributed to insolvency, while cash balances and debt balances had no effect on insolvency. This finding suggests that individual balance sheet accounts are of informational value in predicting insolvency risk.

On the other hand, increases in CEO risk-taking initiatives were found to increase insolvency risk, while CEO risk-reduction practices were found to reduce insolvency risk. Koh and Lee (2017) assessed CEO behavior, concluding that, while CEO risk taking increased insolvency risk, CEOs were sufficiently cautious that evidence of their risk taking did not influence going-concern qualifications. This action reduces the predictive power of going-concern qualifications, placing the burden of improving detection of critical audit factors that predict insolvency risk upon the shoulders of the audit committee. Yet, auditors displayed concern about firms at risk of insolvency by charging higher audit fees for auditing firms with higher managerial risk-taking incentives in both the Chen et al. (2015) study and the Koh and Lee (2017) study. Auditors also considered executive compensation as an incentive for managerial risk taking.

The above discussion suggests that liquidity and executive compensation may increase insolvency risk, although such risk may not be present in going-concern qualifications. Auditor opinions that filter to audit committees have some informational value in predicting firm risk. de Carvalho et al. (2023)’s examination of audits by a variety of auditing firms determined that the auditor opinions of Big 4 accounting firms contained informational value in predicting firm solvency. No such informational value was observed in the auditor opinions of smaller audit firms. In addition, Sun and Liu (2014) revealed that banks with long board tenure audit committees have lower total risk and idiosyncratic risk, and banks with busy directors on their audit committees have higher total risk and idiosyncratic risk.

Nguyen (2021) showed that an audit committee’s independence, number of meetings, and financial expertise negatively affect conventional banks’ risk taking. Thus, the author indicated that the high effectiveness of their audit committees may constrain banks’ risk-taking activities. Therefore, audit committee effectiveness reduces bank risk taking through increasing bank efficiency. Bank efficiency increases audit committee effectiveness, suggesting a bidirectional relationship between audit committee effectiveness and bank efficiency (Nguyen 2022).

2.5. A Critical Analysis of the Literature

Elmarzouky et al. (2022) used a case study approach to investigate the effect of critical audit matters (KAMs) on insolvency risk. The Ernst & Young auditors’ reports based on the annual reports of the Thomas Cook Group failed to predict corporate bankruptcy. This study concluded that international standards of auditing must be strengthened sufficiently to prevent corporate bankruptcy, as KAMs are unable to do so. We feel that this conclusion may be premature, given that the KAMs were analyzed using case study methodology. It is possible that KAMs subjected to empirical testing may yield information that predicts insolvency risk. This study employs empirical testing in its assessment of audit oversight on insolvency risk. Additionally, KAMs are assumed to be of equal importance. That may not be a realistic assumption, given that certain audit matters may take precedence over others. Therefore, instead of evaluating the effect of all KAMs as a single unit, there may be a need to separate those of high importance for firm financial health from those of lesser importance. In this study, we separate audit oversight based on the degree of importance of audit oversight. We distinguish between the frequency of mentioning the term ‘audit committee’ in long paragraphs as audit committee activity of the highest importance in strategic decision making and the frequency of mentioning ‘audit committee’ in all paragraphs, including audit committee activity of both high importance and moderate importance.

Elmarzouky et al. (2024) reviewed 78 studies from 2013 to 2022 to identify research gaps and suggest areas of future research. We identified five gaps revealed in their exhaustive review that pertained to this study as we attempted to seal those gaps in this study. First, they mentioned that Reid et al. (2019) used a single financial year in their analysis, which led to conflicting findings with KAMs either having a positive effect on audit quality, negative effect on audit quality, or insignificant effect on audit quality. We employed 13 years of data from 2010 to 2022 that had both recency and multi-year characteristics. Second, our KAMs were enshrined in the mentioning of ‘audit committee’. This eliminated problems of readability of the KAMs or readability of the audit report (Dobija et al. 2016), as a number was used to measure audit oversight. Third, the review noted that much of the data had non-US sources. It went on to recommend the use of US samples. This study’s data consisted of 597 stocks of publicly traded US firms. Fourth, there was a concern that auditor reports vary in style, structure, and linguistics regarding how they describe KAMs. Measures of KAMs may be subject to errors of interpretation simply because of style of presentation. This study overcame this concern by using the term ‘audit committee’ alone rather than a description containing inconsistencies. Fifth, external audit reports were mentioned as having incremental information that may not be able to identify threats that were not addressed during the audit process. We found that the audit process may be able to identify threats through the ability of audit oversight quality to reduce systematic risk and volatility of return on assets, so that external audit reports may not add much more information.

3. Hypotheses Development

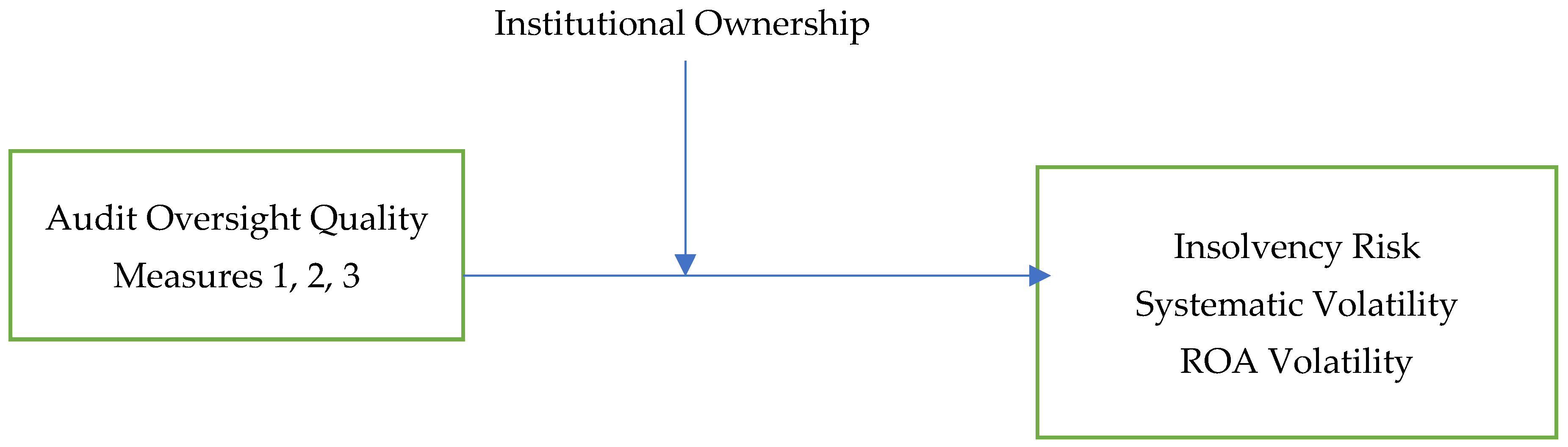

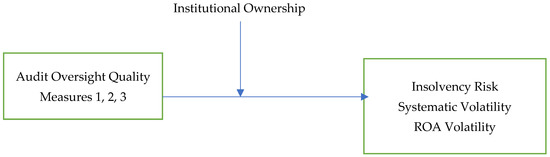

See Figure 1 for a conceptual model of the relationships described in the hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Hypotheses linking audit oversight quality to firm risk.

3.1. Audit Oversight Quality Reduces Insolvency Risk

Audit oversight requires that audit committee members obtain financial reports from auditor firms, which they search for financial concerns that may be raised by the audit firm. There may be misstatements about liquidity, operating income, and sales. All of these figures may be inflated to shed a positive light on the firm’s performance. Overstatement of liquidity suggests that the firm has excessively high cash balances and high working capital balances to permit it to pay for unexpected cash demands. Overstatement of operating income creates the illusion that the firm’s day-to-day operations are more efficient than reality. Overstatement of sales suggests the existence of a fictitious number of customers. By correcting for these overstatements, audit oversight provides accurate inputs into the computation of the Atman Z. The Z values will decline, possibly below the threshold of 1.81, signifying insolvency risk.

Elmarzouky et al. (2022) observed that the identification of critical audit matters (KAMs) is supplemented by the inclusion of incremental information that forecasts threats to the firm. Effective audit oversight can provide such incremental information. Our first measure of audit oversight quality provides the frequency of mentions of ‘audit committee’. It is conceivable that, if critical audit matters identify the incremental information that indicates heightened insolvency risk, an effective audit committee is engaged in evaluating incremental information, discussing incremental information among committee members, and suggesting measures to overcome threats. The intensity of activity of the audit committee is reflected in the number of times the words ‘audit committee’ are mentioned in corporate reports. The second measure of audit oversight quality is the number of times ‘audit committee’ is mentioned in long paragraphs. We surmise that long paragraphs describing audit committee activity contain key financial inputs or critical audit matters of considerable importance, as long paragraphs are needed to describe weighty audit matters. Such key information about weaknesses in liquidity, operating income, and sales increase insolvency risk. The third measure of audit oversight quality is the number of paragraphs that contain the words ‘audit committee’. If audit committees are engaged in uncovering financial irregularities of moderate to high importance, we can expect that their activities will be mentioned in more paragraphs. Both financial irregularities of medium and high importance indicate weaknesses in performance that, if overlooked, may become serious threats to financial stability. By identifying these threats, audit oversight quality may reduce bankruptcy risk.

Hypothesis 1.

Audit oversight quality reduces insolvency risk. Specifically, all three measures of audit oversight quality reduce the Altman Z score either through a linear or non-linear functional forms.

3.2. Audit Oversight Quality Reduces Systematic Risk

Systematic risk is represented by the stock’s beta coefficient. The capital asset pricing model established the link between security returns and the beta coefficient (Sharpe 1964), as presented in the following equation,

where rf is the risk-free rate, is the systematic risk, and is the market risk premium.

As the beta increases, the required return to find the security acceptable for a portfolio increases. The additional return compensates investors for the additional systematic risk that cannot be diversified away. Abraham et al. (2024) showed that effective audit oversight reduced return on equity, reduced debt capacity, and increased firm value. We posit that audit oversight reduces systematic risk, as it provides realistic measures of firm performance, such as return on equity, debt capacity, and firm value. In other words, audit oversight removes overstatement of return on equity, resulting in realistic profit projections. Audit oversight shows how much debt a firm can support by reducing the debt capacity represented by the equity multiplier. Furthermore, audit oversight increases firm value or the excess return of the firm above the cost of capital. Realistic profits, reduced future borrowing, and increased firm value are all positive attributes of firm performance. It follows that such positive attributes reduce investor uncertainty about the firm’s stock, represented by the beta coefficient, so that investors will demand less compensation for accepting firm risk.

Institutional theory sets forth that normative isomorphism prevails in organizations, with its emphasis on meeting professional standards. When the professional standards are formal audit standards, the ability of audit oversight to enforce adherence to standards is a form of oversight. To investors, such audit oversight suggests that the firm’s adherence to professional norms will make it less likely to be sanctioned for failure to comply with industry norms. The reduction in sanctions reduces the risk inherent in the firm that cannot be reduced through diversification; this is systematic risk.

Hypothesis 2.

Audit oversight quality reduces systematic risk. Specifically, all three measures of audit oversight quality reduce the beta coefficients of the sampled securities.

3.3. Audit Oversight Quality Reduces ROA Volatility

Audit committee size, independence, and frequency of meetings have been found to positively impact firm performance. This finding has been documented for UK nonfinancial firms (Alzeban 2023), the French equity index (Barka and Legendre 2017), and Australian materials firms (Gani et al. 2017). The frequency of meetings predictor in these studies is similar to our measures of audit oversight quality. Frequent meetings suggest an active and engaged audit committee that is examining critical audit matters, correcting material misstatements, and devising strategies with the board based on revised financial measures. Similarly, frequent mentions of the phrase ‘audit committee’ in corporate reports suggests that the audit committee is visible and involved in supervising audit firms, determining audit fees, and identifying the critical audit matters that pose threats to the firm.

One of these critical audit matters is the inaccurate statement of net income. Earnings management is the manipulation of earnings reports to present the firm’s earnings in a positive light. Fakhfah and Jarboui (2021) and Saftiana et al. (2017) observed that large audit committees had the skills and expertise to expose earnings management. We posit that, regardless of size, if the audit committee is dedicated and diligent, it will be in a position to reveal earnings management. This revelation will result in realistic measures of earnings and, in turn, net income. These realistic measures will reduce the volatility of net income inherent in earnings management. Why is net income volatile if determined by earnings management? Earnings management alters net income from its true value. The extent of effectiveness of earnings management varies over time. During certain periods, earnings management will be very effective, resulting in net incomes that wildly diverge from true values. At other times, earnings management will be less effective, so that net incomes are closer to true values. This leads to volatility in return on assets, which is computed using net income. Audit oversight quality forces net income figures to be at true values at all times, eliminating the volatility brought about by earnings management.

Resource dependence theory maintains that firms consist of relationships based on dependence on shared resources. The audit committee provides quality financial reports in its function of providing resources to the rest of the organization. The provision of accurate profit figures and accurate sales figures reduces variations in profit estimates and sales estimates. By monitoring the reporting of expenses, revenue, and cash flows, audit committees can correct errors in these figures. This leads to clear, error-free, and consistent reports. Such reports can be used by marketing departments to determine their current performance, which is the input into creating performance targets for the future. Production can use accurate sales figures to set realistic production targets. In the absence of audit oversight, neither marketing departments nor production departments can set realistic goals, increasing firm risk. Therefore, audit oversight quality reduces the volatility of return on assets.

Hypothesis 3.

Audit oversight quality reduces volatility of return on assets. Specifically, all three measures of audit oversight quality reduce standard deviation of return on assets of the sampled securities.

3.4. Institutional Ownership Interacts with Audit Oversight Quality to Reduce Firm Risk

The literature supports the corporate governance function of institutional ownership as having joint effects with the internal audit function and audit committee effectiveness. Al-Jaifi et al. (2019) used a sample of Malaysian firms to demonstrate that institutional investors have preference for firms with effective audit committees, as such committees assume the monitoring costs that would otherwise be the responsibility of institutional investors. Al-Musali et al. (2019) identified institutional ownership as a complement to audit committee effectiveness among the top-capitalized firms in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Hassan et al. (2017) found a negative relationship between institutional ownership and audit committee effectiveness, suggesting that the two variables are substitutes as they both measure the same underlying construct of corporate governance.

Audit oversight quality is a measure of corporate governance. It reduces the likelihood of using manipulated financial data to make strategic decisions. It suggests prudence in reporting profits, debt capacity, and firm value (Abraham et al. 2024). Such prudence is the antithesis of reckless risk taking. Reckless risk taking encourages investment in ventures with minimal chance of success and misuse of cash to yield private benefit. Institutional investors represent life insurance companies and pension funds. These investors have a long-term view, choosing long-term value over current benefits. Long-term value is achieved by disciplined continuous investment in value-adding securities. It abhors quick profit for the prudence of disciplined long-term investment. In short, the prudence of institutional investors is matched by the prudence of audit oversight quality. The joint conservatism of both institutional ownership and audit oversight quality reduces firm risk.

Hypothesis 4.

The joint effect of audit oversight quality and institutional ownership reduces insolvency risk, reduces systematic risk, and reduces volatility of return on assets.

4. Methods and Materials

4.1. Data Collection

We selected the pharmaceutical industry and the energy industry in the United States as the data sources. These industries are heavily regulated, with regulation providing some governance in its requirement that firms comply with industry standards. We reasoned that, in such industries, audit oversight quality will provide a measure of governance that is attributed to firm characteristics rather than the need to strengthen governance to comply with industry standards.

Three measures of audit oversight quality were created. In the United States, publicly traded firms are required to file annual reports, Form 10Ks, Form 10Qs, and DEF13A reports. The SeekEdgar database employs an algorithm that uses a search term to extract information from these reports. For example, upon using the term ‘audit committee’, SeekEdgar will extract the number of times the words ‘audit committee’ appear in all reports, along with the number of paragraphs in which the words appear. The SeekEdgar database was used to extract words, phrases, and paragraphs from annual reports, Form 10Ks, and Form 10Qs for 597 U.S. pharmaceutical securities and energy securities from 2010 to 2022. Upon searching for the words ‘audit committee’, we obtained the first measure of audit oversight quality as the total frequency with which ‘audit committee’ was mentioned in the reports. We maintained that the more frequently the term ‘audit committee’ was mentioned in company reports, the more likely the audit committee was engaged in examining audit reports to locate material misstatements, which, upon correction, can provide accurate financial information for strategic decision making. In other words, an audit committee that is actively engaged in providing oversight will be mentioned more frequently than an inactive audit committee. We obtained the second measure as the total number of long paragraphs (>300 words) containing the words ‘audit committee’. We posit that long paragraphs contain contributions to a firm’s policy of strategic importance, so that the engagement by audit committee members in these weighty decisions is a measure of their oversight that provides key input into strategic decision making. Long paragraphs contain a wealth of detail that describe the significant contribution that audit committee members make in taking information from the audit reports and employing them in the decision making of complex decisions. Such decisions are sufficiently complex to involve a multi-step process, resulting in long paragraph descriptions. The third measure of audit oversight quality was the total number of paragraphs with the words ‘audit committee’, suggesting audit committee engagement in both key strategic decisions and moderately important strategic decisions, as such decisions are described in paragraphs. The total number of paragraphs included audit committee involvement in both highly complex decisions in long and less complex decisions in short paragraphs. The total number of paragraphs described audit committee engagement in multistep and single-step decisions.

The remaining balance sheet measures of volatility of return on assets, components of z, leverage, total assets, and tangibility were obtained from the COMPUSTAT database. Market measures such as beta, institutional ownership, and the audit committee governance measure were provided by Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), which is majority owned by Deutsche Börse Group, and, along with ISS management, is a private firm that collects corporate governance, market intelligence, fund services, events, and editorial content for institutional investors and corporations, globally.

Table 1 provides a list of dependent variables, independent variables, and control variables.

Table 1.

List of dependent variables, independent variables, and control variables.

4.2. Data Analysis

Panel data fixed effects regressions of risk measures on audit oversight quality were conducted, as shown in Equations (1)–(3). Equation (4) tests the moderation by institutional ownership. Then, similar panel data fixed effects regressions using the ISS alternate governance measure were conducted to check the robustness of audit oversight quality as measures of corporate governance in Equation (5). Finally, endogeneity tests to determine whether audit oversight quality measures were measuring other variables were performed, using two-stage least squares. In the first stage, leverage, firm size, equity multiplier, and firm value were regressed on audit oversight quality measures, which acted as dependent variables. In the second stage, the exogeneous variable of the effect of leverage, firm size, equity multiplier, and firm value on audit oversight quality was regressed on the three risk measures.

5. Results

5.1. Results of Hypotheses Tests

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix of key variables.

As Table 2 shows, observed firms on average used 30% leverage financing and were less volatile than the market, since = 0.97.

As shown in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, Hypothesis 1 was not supported, as audit oversight quality measures failed to significantly reduce insolvency risk. This was true of both linear and non-linear functional forms. Hypothesis 2 was supported. Audit oversight quality measure 1 significantly reduced systematic risk (coefficient = −3.97 × 10—6, p < 0.001, Table 4). Audit oversight quality measure 2 significantly reduced systematic risk (coefficient = −0.01, p < 0.001, Table 5). Hypothesis 3 was supported. Audit oversight quality measure 1 significantly reduced volatility of return on assets (coefficient = −0.001, p < 0.001, Table 4). Audit oversight quality measure 3 significantly reduced volatility of return on assets (coefficient = −0.02, p < 0.001, Table 6).

Table 4.

Fixed effects panel data regressions of audit oversight quality 1 on firm risk.

Table 5.

Fixed effects panel data regressions of audit oversight quality 2 on firm risk.

Table 6.

Fixed effects panel data regressions of audit oversight quality 3 on firm risk.

Hypothesis 4 was supported. The joint effect of audit oversight quality and institutional ownership decreased all three measures of risk. Table 7 shows that the interaction of the first audit oversight quality measure with institutional ownership and the interaction of the third audit oversight quality measure with institutional ownership decreased systematic risk. Table 8 shows that the joint effect of the second audit oversight quality measure and institutional ownership decreased both insolvency risk and systematic risk. Table 9 shows that the interaction of the third audit oversight quality measure with institutional ownership decreased the volatility of return on assets.

Table 7.

Fixed effects panel data regressions of audit oversight quality 1 on firm risk with institutional oversight as moderator.

Table 8.

Fixed effects panel data regressions of audit oversight quality 2 on firm risk with institutional oversight as moderator.

Table 9.

Fixed effects panel data regressions of audit oversight quality 3 on firm risk with institutional oversight as moderator.

5.2. Robustness Check

Robustness of the effects of audit oversight quality on firm risk was checked by repeating the regressions in Table 3 with an alternate governance measure. We reasoned that, if audit oversight quality was a true measure of corporate governance, an alternate measure of corporate governance would also reduce firm risk. Table 10 shows the effect of the alternate measure of governance on firm risk. Results are similar to the effects of audit oversight quality on firm risk with significant reductions in systematic risk and volatility of the return on assets. This finding establishes that the measures of audit oversight quality measure corporate governance.

Table 10.

Fixed effects panel data regressions of an alternative audit quality measure on firm risk.

5.3. Endogeneity Tests

We tested whether leverage, firm size, debt capacity (equity multiplier), and firm value influenced risk through their effect on audit oversight quality. As Table 11 shows, the first stage of a two-stage least squares regression failed to observe significant effects of any of these variables on the three measures of audit oversight quality. The limited significance of these variables affecting audit oversight quality’s influence on firm risk in the second stage was marginal, as it was only confined to the first measure of audit oversight quality. We concluded that audit oversight quality measures are exogeneous measures in their effects on firm risk, which are not explained by other variables.

Table 11.

Two-stage least squares test of endogeneity of three audit quality measures.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Discussion of Results

Audit oversight quality measures differ in their impact on firm risk, indicating differences in their informational value. Audit oversight quality measure 1 is an overall measure of all sources of financial irregularities and their correction; hence, it reduces both systematic risk (an external measure of risk) and volatility of return on assets (the internal measure of risk). Audit quality measure 2 recognizes audit committee engagement in key strategic decisions. Such engagement is effective in reducing systematic risk. Audit quality measure 3 assesses audit committee participation in strategic decisions of moderate to high importance. This involvement reduces the volatility of return on assets.

Systematic risk is represented by the stock’s beta coefficient. As the beta rises, so does the threshold return required to make the stock acceptable for a portfolio as the stock becomes more risky. By providing corrections to financial irregularities that are inputs into key strategic decisions, audit oversight quality reduces the threshold risk to find a security acceptable for a portfolio. Therefore, audit oversight quality promotes the creation of portfolios that contain a wider selection of securities. Thus, audit oversight quality increases portfolio diversification, which is the cornerstone of risk reduction.

Risk from the volatility of return on assets is an internal risk measure as it is computed from the balance sheet accounts of net income and total assets. Audit oversight quality reduces this risk by exposing earnings management with excessive accruals and excessive discretionary expenses. As this exposure leads to better strategic decisions of moderate to high importance, audit oversight quality serves as an internal audit function.

Institutional ownership strengthens the effects of the second and third measures of audit oversight quality. As noted, the second measure of audit oversight quality reduces systematic risk. With institutional quality, this measure of audit oversight quality reduces the volatility of return on assets. Audit oversight quality’s corporate governance effect on external risk is complemented by institutional ownership’s corporate governance effect on the internal audit function. A converse effect exists with the third measure of audit oversight quality. As the third measure reduces the volatility of return on assets (which is an input into the internal audit function), institutional ownership supplements it by reducing external risk from investors who feel more confident about the stock.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

Much of the literature pertains to risk reduction in the form of insolvency risk (Chen et al. 2015; Koh and Lee 2017); yet, this study found no significant reduction in insolvency risk by any of the audit oversight quality measures. We surmise that actively engaged audit committee members can provide accurate financial measures that increase internal firm confidence and external investor confidence, which, in turn, reduce systematic risk and volatility of return on assets. Such engagement has been identified as audit committee independence, a large number of audit committee meetings, and financial expertise among audit committee members (Nguyen 2021). Nguyen (2022) observed that the greater efficiency from this audit committee engagement reduced bank risk taking.

This study suggests that effective audit oversight limits agency costs by reducing risk. Effective oversight prevents management from increasing accruals and increasing discretionary expenses, both of which may contain additional amounts allocated for management’s private expenses and perquisites. With effective audit oversight, investors perceive greater control of incremental expenses so that their confidence in the firm grows, reducing systematic risk. As internal managers and employees perceive constant values of net income leading to stable profitability measures, they may be reassured that earnings manipulations, such as earnings management, are absent. This outcome reduces the volatility of return on assets. In sum, by restricting management’s ability to alter accounts to serve their own interests, audit oversight limits agency costs, which reduces firm risk.

The finding that institutional ownership as a governance measure strengthens the ability of audit oversight quality to reduce firm risk. Institutional owners are typically pension funds and life insurance companies that command vast assets under management. Fund managers are in regular communication with the firm as the firm solicits investment from the fund managers. The firm can provide evidence that audit oversight reduces firm risk to fund managers, who may be encouraged to invest in the firm’s stock.

However, this study explains only some of the prior findings of audit committee containment of agency conflicts. Francis and Wilson (1988) and Kalbers and Fogarty (1998) set forth that audit committee effectiveness was not explained by reduction of agency conflict. Perhaps, their measures of audit committee effectiveness did not have the same informational value as the measures used in this study. Dey (2008)’s finding of greater reduction of agency conflict due to audit committee independence and composition in high agency conflict environments is puzzling as it assumed that corporate governance was only effective under certain conditions. Future research should replicate the Dey (2008) study under varying agency conflict conditions to determine whether audit oversight can be effective in reducing agency conflicts in low agency conflict situations.

Elmarzouky et al. (2024)’s review uncovered areas of future theoretical investigation. They called for a longitudinal study linking management risk reporting with audit firm risk reporting. This study provides some evidence of risk reporting by the audit firm. This study can be extended over a long period of time, such as 20 years, to measure the effect of audit oversight quality measures on insolvency risk, systematic risk, and volatility of return on assets. This audit firm risk reporting can be related to management risk reporting to compare whether both sources of oversight have similar effects on firm risk. Another area listed by Elmarzouky et al. (2024) is the need to increase the informativeness of audit reports. This would require reports that do not rigidly conform to established practice, such as maintaining a positive tone upon the impartation of negative news. The audit oversight quality measures used in this study may be employed by adding words and phrases indicating informativeness, such as ‘negative news’, to the search term of ‘audit committee’ in the Seekedgar database, which will extract the number of times the audit committee presented negative news of firm performance to the board. This frequency can then be used to predict firm risk. We hypothesize that increased informativeness due to positive news will reduce firm risk, while increased informativeness due to negative news will increase firm risk.

6.3. Practical Implications

Firms need to reduce risk. Internally, risk reduction boosts confidence among employees and managers. Externally, markets and investors value the firm’s stock at higher values with reduced risk. As audit oversight provides for external risk reduction by reducing external systematic risk and internal volatility of return on assets, firms need to have actively engaged audit committees. Engagement must take the form of hiring reputable audit firms, examining their findings pertaining to excessive accruals, excessive discretionary expenses, critical audit matters, debt, and earnings management. This information must become an input into the strategic decision-making process. Therefore, audit committee members must clearly communicate the financial irregularities found in audit reports and their adverse effects on firm risk. These adverse effects may include reputational damage, accompanied by irreversible losses of customers and markets.

Stakeholder theory maintains that the firm must balance the needs of vendors, customers, regulators, labor unions, and other stakeholders (Freeman 1984). Such a balance may be achieved by the transparent and accurate financial statements that are the product of audit oversight. The different entities may decide to forego continuing business with the firm if they feel that the firm is concealing its true profits, sales figures, and expenses. Vendors may feel that they will not be paid if the firm is less profitable than is apparent. Employees may fear layoffs. Unions may become hostile if they feel that wage increases are not forthcoming. Regulators may impose sanctions if investments in meeting compliance requirements are not made.

Other practitioner implications pertain to fund managers, firms, and regulators. Mutual funds serve as a savings vehicle for households. Fund managers can use findings to find less risky securities. Such low-risk investments, i.e., with low betas and less volatility of return on assets, will be suited to the investment needs of small investors who do not have the large asset base to withstand losses from risky investments. Firms may wish to strengthen their audit oversight. They need to have dynamic creative accountants and non-accountants on their audit committees who will take the lead in enacting strategies to monitor management, reduce earnings management, and prevent material misstatements. Non-accountants play an important role on audit committees as they communicate financial information to other departments within the firm. Regulators should insist that firms have active audit committees, measured by the frequency of mentioning the term ‘audit committee’ in firm reports. If the frequency of the term ‘audit committee’ decreases in firm reports, regulators can demand that members of the audit committee be replaced until the frequency rises to its normal level.

6.4. Economic Implications

The results have implications for investors and other stakeholders. Audit oversight reduces the stock’s beta coefficient, suggesting that an investment in the stock will reduce the non-diversifiable risk of the stock. As per CAPM, the required return to find the security acceptable for inclusion in a portfolio will decrease, expanding the universe of securities available for portfolio creation. Call option traders will envision gains from increases in security prices, encouraging call option purchases. The Miller price optimism model (Miller 1977) envisions a market in which optimists will trade based on positive information, while pessimists will refrain from trading due to high short-sale costs. In keeping with this model, audit oversight may encourage optimists to purchase securities of firms with high levels of audit oversight, and trading volume is expected to surge.

The reduction of ROA volatility would be of interest to institutional investors. ROA volatility suggests risk from varying profits. The inability to accurately forecast profits due to this variation increases uncertainty for institutional investors. Since institutional investors have large amounts of funds to invest, they have numerous choices for investment, These investors may abandon securities with high ROA volatility. As this study has shown that audit oversight quality reduces ROA volatility, it may encourage institutional investors to continue to invest in the securities of firms whose ROA volatility has been reduced by effective audit oversight.

6.5. Summary of Findings: Policy and Practice Implications

The findings of this study are as follows:

- Audit oversight quality has not been shown to reduce insolvency risk.

- Audit oversight quality measures of total frequency and audit committee input into important decisions reduce systematic risk.

- Audit oversight quality measures of total frequency and audit committee input into decisions of moderate to high importance reduce volatility of return on assets.

- The joint effect of audit oversight quality and institutional ownership reduces systematic risk and volatility of return of assets.

Audit policies may be shaped by these results. Professional standards must emphasize the need for audit committees to be engaged in monitoring both important decisions and decisions of moderate importance to the firm. This will strengthen the firm’s beta coefficient, making it more appealing to regulators and investors. Regulators will view the reduction in risk favorably, making them less likely to impose sanctions and fines on the firm. Investor confidence will increase, possibly leading to an inflow of investment capital. Institutions are exacting in their assessments of firms. They regularly downgrade firms perceived as being risky investments for their members. They will support firms whose audit oversight leads to less volatile profit figures, as stable consistent profits suggest financial health. They will be supportive of firms with strong audit oversight, as they can trust the profit figures published by such firms. Therefore, less volatile ROA from audit oversight may result in institutions keeping these stocks in their portfolios.

6.6. Research Limitations

This study did not find any prediction of insolvency risk by audit oversight quality; yet, the alternate governance measure observed insolvency risk reduction. Perhaps, the informational value of the existing audit oversight quality measures may be enhanced with additional measures. These measures may rate audit committee actions on a scale of 1–3, signifying the effect on liquidity, sales, or earnings of audit committee actions, as such actions have been shown to reduce insolvency risk. Future research should conduct such an investigation.

Total frequency of mention of ‘audit committee’ showed stronger effects as an audit oversight measure on the reduction of firm risk than either frequency of ‘audit committee’ listing in long paragraphs or all paragraphs. This finding pertained to contemporaneous measurements. Future research should investigate the consistency of this finding over time by employing the same sample over a longer 15–20 year period.

The reduction of agency conflict by audit oversight quality may need additional investigation. Given Dey (2008)’s finding of more effective corporate governance in high agency conflict environments, this study should be replicated in such environments to determine whether these measures of audit oversight quality have the same effects as those in the Dey (2008) investigation.

The sampled firms belonged to the pharmaceutical industry and the energy industry, both of which are heavily regulated. Future research should measure the effect of audit oversight quality on less regulated industries. As regulation is a form of governance, less regulated industries may show purer effects of audit oversight quality on firm risk, as any compounding effect of governance by regulation will be absent.

Other questions pertain to the control variables. What is the effect of leverage on insolvency risk if firms that use more leverage have higher risk than counterparties that are financed through equity? It would appear that leveraged firms have more risk, so future research should measure the effects of audit oversight quality on insolvency risk for separate samples of firms financed with debt and firms financed with equity.

Does firm size matter, in the sense that large firms have more risk than others? Does a higher tangibility ratio signify higher risk? By repeating the regressions of audit oversight quality with varying levels of firm size and tangibility, the extent of risk reduction may change. Future research should determine whether audit oversight quality reduces risk more or less among large firms and small firms. Similarly, future research should determine whether audit oversight quality reduces risk more or less among tangible firms with large fixed-asset investment or less tangible firms with less fixed-asset investment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.; Methodology, R.A. and F.D.; Software, H.E.-C.; Validation, R.A. and F.D.; Formal Analysis, R.A.; Investigation, H.E.-C.; Resources, H.E.-C.; Data Curation, R.A. and F.D.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, R.A.; Writing—Review and Editing, H.E.-C. and F.D.; Visualization, R.A. and H.E.-C.; Supervision, R.A.; Project Administration, H.E.-C. and F.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the first author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abolmohammadi, Mohammad. 2009. Factors associated with the use of and compliance with the IIA standards: A study of anglo-culture CAEs. International Journal of Auditing 13: 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, Rebecca, Hani El-Chaarani, and Zhi Tao. 2024. The impact of audit oversight quality on the financial performance of U.S. firms: A subjective assessment. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 17: 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahdal, Waleed M., and Hafiza Aishah Hashim. 2022. The impact of audit committee characteristics and external audit quality on firm performance: Evidence from India. Corporate Governance 22: 4240–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Md Hassan, and Mohammad Rajon Meah. 2021. Factors of audit committee independence: An empirical study from an emerging economy. Cogent Business and Management 8: 1888678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaifi, Hamdan, Amer Ahmed Hussein Al-Rassas, and Adel Al-Qadasi. 2019. Institutional investor preferences: Do internal auditing function and audit committee effectiveness matter in Malaysia? Management Research Review 41: 641–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Musali, Mahfoudh Abdulkarem, Mohammed Helmi Qeshta, Mohamed Ali Al-Attafi, and Abood Mohammad El-Ebel. 2019. Ownership structure and audit committee effectiveness: Evidence from top GCC capitalized firms. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 12: 407–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Twaijry, Abdulrahman A. M., John A. Breirley, and David. R. Gwilliam. 2003. The development of internal audit in Saudi Arabia: An institutional theory perspective. Critical Perspectives in Accounting 14: 507–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzeban, Abdulaziz. 2015. Influence of audit committees on internal audit conformance with internal auditing standards. Managerial Auditing Journal 30: 539–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzeban, Abdulaziz. 2023. Internal audit findings, audit committees, and firm performance: Evidence from UK. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting and Economics 30: 868–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, Marika, and Giovanni Azzone. 2009. Identifying organizational drivers of internal audit effectiveness. International Journal of Auditing 13: 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayman, Hassan Bazhair. 2022. Audit committee attributes and financial performance of Saudi non-financial listed firms. Cogent Economics and Finance 10: 2127238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barka, Hazar Ben, and Francois Legendre. 2017. Effect of the board of directors and audit committee on firm performance. Journal of Management and Governance 21: 737–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bens, Daniel, Woo-Jin Chang, and Sterling Huang. 2019. The Association between the Expanded Audit Report and Financial Quality. Working Paper. Singapore: Singapore Management University. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Victor Zitian, Jing Li, and Daniel M. Shapiro. 2011. Are OECD-prescribed “good corporate governance practices” really good in an emerging economy? Asia Pacific Journal of Management 28: 115–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yangyang, Ferdinand A. Gul, Madhu Veeraghavan, and Leon Zolotoy. 2015. Executive equity risk-taking incentives and audit pricing. The Accounting Review 90: 2205–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, Paul Viegas, Joaquim Ferrao, Joaquim Santos Alves, and Manuela Sarmento. 2023. The informational value contained in the different types of auditor’s opinions: Evidence from Portugal. Cogent Economics & Finance 11: 2162688. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, Aiyesha. 2008. Corporate Governance and Agency Conflicts. Journal of Accounting Research 46: 1143–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobija, Dorota, Iwona Cieslak, and Katarzyna Iwue. 2016. Extended audit reporting: An insight from the auditing profession in Poland. Zeszyty Teoretyczne Rachunkowosci 86: 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmarzouky, Mahmoud, Khaled Hussainey, and Tarek Abdulfattah. 2022. Do key audit matters signal corporate bankruptcy? Accounting and Management Information Systems 21: 315–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmarzouky, Mahmoud, Khaled Hussainey, and Tarek Abdulfattah. 2023. The key audit matters and the audit cost: Does governance matter? International Journal of Accounting and Information Management 31: 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmarzouky, Mahmoud, Khaled Hussainey, and Tarek Abdulfattah. 2024. Key audit matters: A systematic review. International Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Performance Evaluation 20: 319–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhfah, Iman, and Anis Jarboui. 2021. The moderating role of audit quality on the relationship between auditor reporting and earnings management: Evidence from Tunisia. EuroMed Journal of Business 16: 416–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, I. 2008. The effect of audit committee composition and structure on the performance of audit committees. Meditari Accountancy Research 16: 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Jere R., and Earl R. Wilson. 1988. Auditor Changes: A Joint Test of Theories Relating to Agency Costs and Auditor Differentiation. Accounting Review 63: 663–82. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/247906 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Freeman, R. Edward. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pittman: Hachette Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Gani, Ismail, Albert Wijeweera, and Jan Eddie. 2017. Audit committee compliance and firm performance nexus: Evidence from ASX listed companies. Business and Economic Research 7: 135–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Geiger, Marshall, and Kannan Raghunandan. 2002. Auditor tenure and reporting failures. Auditing: Journal of Practice and Theory 21: 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, Abdul. 2013. Pengaruh Kompetensi dan Independensi Auditor Terhap dan Kualitas Audit Denggan Angarran Waktu Audit dan Komitmen Profesional Sebagu Variabel Moderasi. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University Brawjaya Malang, Jawa Timur, Indonesia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Yousef, Rafiq Hijazi, and Kamal Naser. 2017. Does audit committee substitute or complement other corporate governance mechanisms: Evidence from an emerging economy. Managerial Auditing Journal 32: 658–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, Amy J., and Thomas Dalziel. 2003. Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Academy of Management Review 28: 383–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, Adrienna, Monet Lee, and David Plastino. 2023. Going-concern qualifications: A reliable predictor of insolvency. ABI Journal 1: 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ishak, Suhaimi. 2016. Going-concern Audit Report; The role of audit committee. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 6: 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Michael C., and Williiam H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbers, Lawrence P., and Timothy Fogarty. 1998. Organizational and Economic Explanations of Audit Committee Oversight. Journal of Managerial Issues 10: 129–50. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40604189 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Koh, Wei-Chern, and Kin-Wai Lee. 2017. Do auditors recognize managerial risk-taking incentives? International Journal of Business 22: 206–29. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, John W., and Brian Rowan. 1977. Institutional organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology 82: 340–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Edwin. 1977. Risk, uncertainty, and divergence of opinion. Journal of Finance 32: 1151–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Sherliza Paul, and Susala Devi. 2013. Audit committee experts and earnings quality. Corporate Governance 13: 335–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Quang Khai. 2021. Oversight of bank risk-taking by audit committees and Sharia committees: Conventional vs. Islamic banks. Heliyon 7: e07798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Quang Khai. 2022. Audit committee effectiveness, bank efficiency and risk-taking: Evidence in ASEAN countries. Cogent Business & Management 9: 2080622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeranz, Felix. 1997. Audit committees: Where do we go from here? Managerial Auditing Journal 12: 281–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porumb, Vlad-Andrei, Yasmini Zengin-Karairaghimoglu, Gerald J. Lobo, Reggy Hooghiemstra, and Dick De Ward. 2021. Expanded auditors report disclosures and loan contracting. Contemporary Accounting Research 38: 3214–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, Lauren C., Joseph V. Carcello, Chan Li, Terry L. Neal, and Jere R. Francis. 2019. Impact of auditor report changes on financial reporting quality and audit costs: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Contemporary Accounting Research 36: 1501–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saftiana, Yulia, Mukhtaruddin Mukhtaruddin, Kristina Winda Putri, and Ike Sasti Ferina. 2017. Corporate governance quality, firm size, and earnings management: Empirical study in Indonesian Stock Exchange. Investment Management and Financial Innovation 14: 105–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vineeta, Vic Naiker, and Barry Lee. 2009. Determinants of audit committee meeting frequency: Evidence from a voluntary governance system. Accounting Horizons 23: 245–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, William F. 1964. Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. Journal of Finance 19: 425–42. [Google Scholar]

- Shetnawi, Saddam Ali, Ahmad Marei, Mustafa Mohd Hanefa, Marther Eddaiaia, and Saeed Alaaraj. 2021. Audit committee and financial performance in India. Montegrin Journal of Economics 1: 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Stroh, Linda K., Jan M. Brett, Joseph P. Baumann, and Anne H. Reilly. 1996. Agency Theory and Variable Pay compensation strategies. Academy of Management Journal 39: 751–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Jerry, and Guoping Liu. 2014. Audit committees’ oversight of bank risk-taking. Journal of Banking & Finance 40: 376–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Alex P., and Li Xu. 2007. Institutional Ownership and Internal Control Material Weakness and Firm Performance. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1031270 (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Vadasi, Christina, Michalis Bekaris, and Andreas Andrikopoulos. 2020. Corporate governance and internal audit: An institutional theory perspective. Corporate Governance 20: 175–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolnizer, Peter W. 1995. Are audit committees red herrings? Abacus 31: 45–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).