Determinants of Stochastic Distance-to-Default

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Stochastic Distance-to-Default Raises Management Concerns

1.2. Objectives

1.3. Contribution

2. Literature Review

2.1. Company-Specific Indicators and the Distance-to-Default

2.2. Country-Specific Indicators and the Distance-to-Default

2.3. Industry-Specific Factors and Distant to Default

3. Data

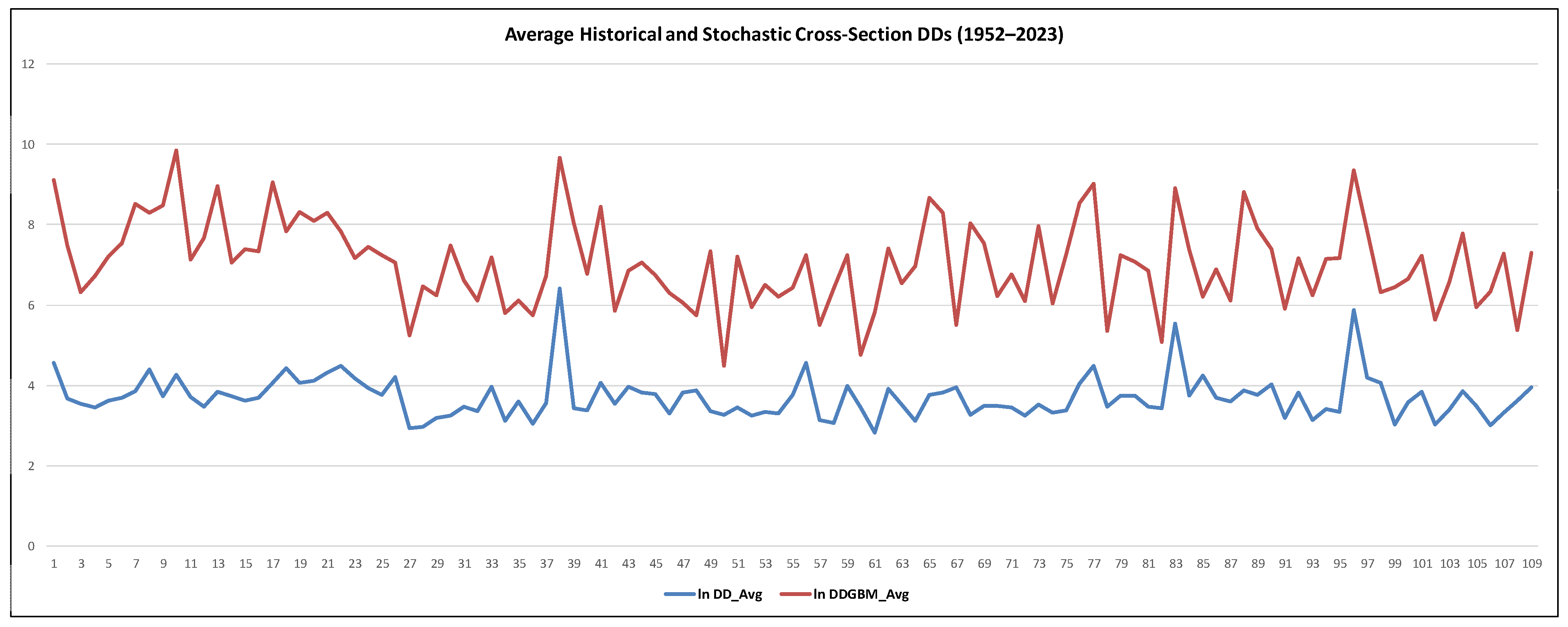

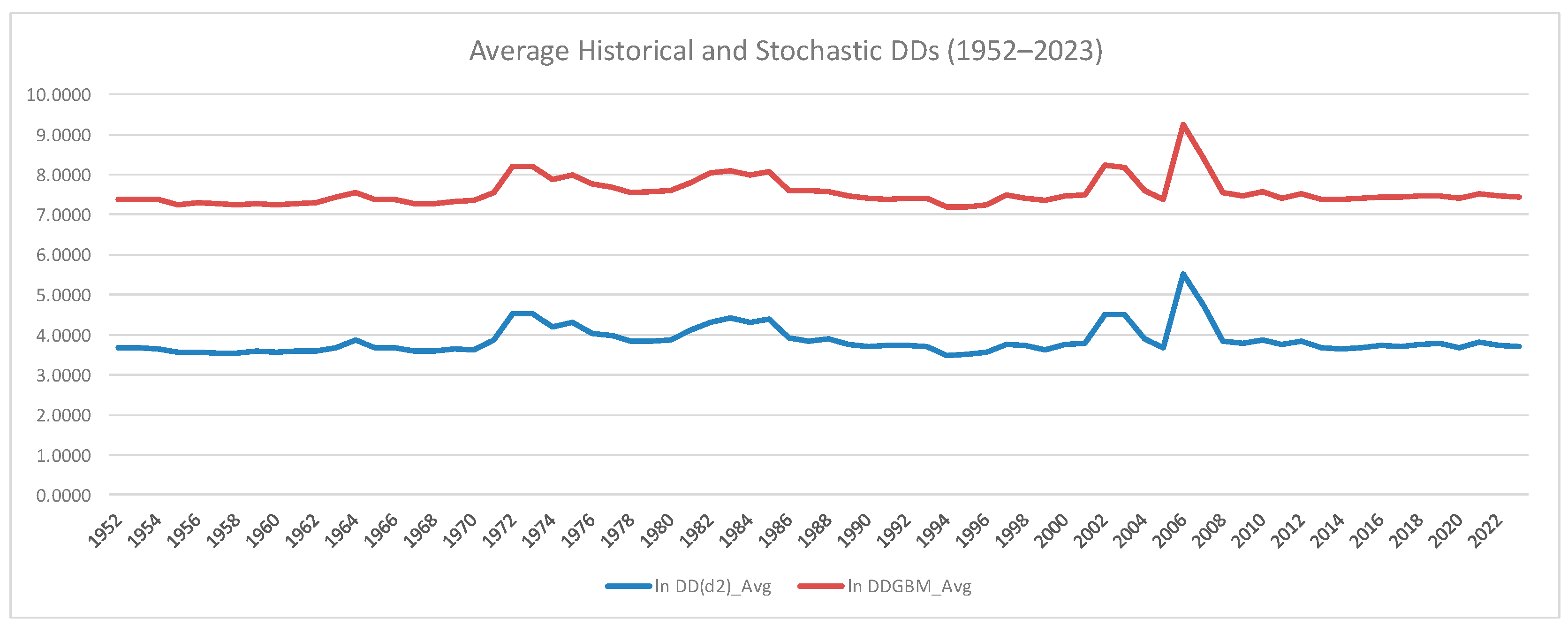

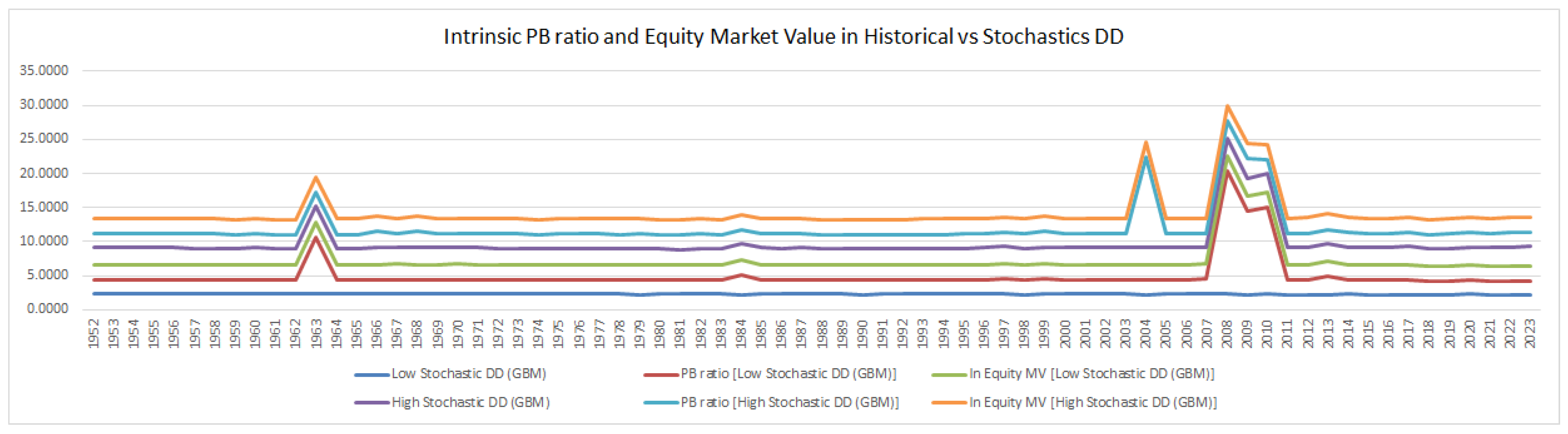

3.1. Dependent Variable

3.2. Independent Variables

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

- A reduction in debt financing proportional to equity financing;

- The inclusion of tax savings in the determination of debt financing;

- An adoption of marketing strategies that promote sales growth;

- Making investment decisions that strengthen companies’ market value in the stock market;

- An adoption of targets derived from the industry, specifically, the industry average retail inventory to sales.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Mean | Standard Error | Kurtosis | Skewness | Minimum | Maximum | Count | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance-to-Default (DD) | 51.404 | 3.505 | 3542.904 | 52.993 | 0.161 | 22,439.132 | 7848 |

| DD using GBM | 40.457 | 0.458 | 8.820 | 2.372 | 187.328 | 271.138 | 7848 |

| Debt-to-Equity | 5.507 | 1.467 | 2490.441 | 48.339 | 1.632 | 9.778 | 7848 |

| Effective Tax Rate | 0.726 | 0.346 | 2204.120 | −5.219 | −1775.026 | 1431.973 | 7848 |

| Bankruptcy Costs | −9.592 | 0.307 | 173.860 | −1.923 | −728.040 | 606.627 | 7848 |

| Growth of Free Cash Flow | −0.015 | 1.849 | 1290.912 | −22.739 | −0.074 | 0.548 | 7848 |

| Return on Assets | 0.034 | 0.017 | 5599.665 | 72.226 | −14.054 | 118.451 | 7848 |

| Price-to-Earnings per Share | 192.239 | 51.077 | 5889.682 | 72.757 | −16,658.600 | 372,840.930 | 7848 |

| Size (ln Sales Revenue) | 20.133 | 0.037 | 17.563 | −3.239 | 0.000 | 25.625 | 7848 |

| Size (ln Market Value) | 21.464 | 0.062 | 9.370 | −3.072 | 0.000 | 31.869 | 7848 |

| Growth of GDP | 0.012 | 0.000 | 6.163 | −1.802 | −0.020 | 0.024 | 7848 |

| Inflation Rate | 0.005 | 0.039 | 38.883 | −6.226 | −0.003 | 0.018 | 7848 |

| Productivity Growth | 0.044 | 0.001 | 1.837 | −1.165 | −0.130 | 0.129 | 7848 |

| % Change in Manufacturing Output | 0.017 | 0.001 | 3.214 | −1.489 | −0.209 | 0.109 | 7848 |

| T-Bills | 0.033 | 0.000 | −1.227 | −0.360 | 0.000 | 0.061 | 7848 |

| Growth Unemployment Rate | 0.005 | 0.001 | 1.842 | 1.074 | −0.103 | 0.164 | 7848 |

| Industry Retail Inventory to Sales | 0.016 | 0.000 | −0.482 | −0.235 | 0.014 | 0.017 | 7848 |

| Industry Growth Sales (Retail) | 0.010 | 0.000 | 580.594 | −16.320 | −0.755 | 0.036 | 7848 |

| Industry Growth Inventory (Wholesalers) | 0.012 | 0.000 | 17.647 | −3.675 | −0.141 | 0.044 | 7848 |

| 1 | |

| 2 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/searchresults/?st=Industrial%20Production (accessed on 1 May 2023). |

| 3 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GOMA (accessed on 1 May 2023). |

| 4 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/categories/116 (accessed on 1 May 2023). |

| 5 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE/ (accessed on 1 May 2023). |

| 6 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/searchresults/?st=retail%20inventory%20to%20sales%20 (accessed on 1 May 2023). |

| 7 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WHLSLRIRSA (accessed on 1 May 2023). |

| 8 | https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WHLSLRIMSA (accessed on 1 May 2023). |

References

- Affandi, F., Sunarko, B., & Yunanto, A. (2019). The impact of cash ratio, debt to equity ratio, receivables turnover, net profit margin, return on equity, and institutional ownership to dividend payout ratio. Journal of Research in Management, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, K., & Maheshwari, Y. (2014). Default risk modelling using macroeconomic variables. Journal of Indian Business Research, 6(4), 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E. I. (1968). The prediction of corporate bankruptcy: A discriminant analysis. The Journal of Finance, 23(1), 193–194. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, E. I., Iwanicz-Drozdowska, M., Laitinen, E. K., & Suvas, A. (2016). Financial and non-financial variables as long-horizon predictors of bankruptcy. Journal of Credit Risk, 12(4), 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E. I., & Saunders, A. (1998). Credit risk measurement: Developments over the last 20 years. Journal of Banking & Finance, 21(11–12), 1721–1742. [Google Scholar]

- Alworth, J., & Arachi, G. (2003, July 15–16). An integrated approach to measuring effective tax rates. CESifo Conference on “Measuring the Tax Burden on Labour and Capital” (pp. 15–16), Venice, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M. H., & Prezas, A. P. (2003). Asymmetric information, asset allocation, and debt financing. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 20(2), 127–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, A. J. (1985). Real determinants of corporate leverage. In B. M. Friedman (Ed.), Corporate capital structure in the United States (pp. 301–322). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, H. (2021). Unemployment and credit risk. Journal of Financial Economics, 142(1), 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiari, S. (2017). Corporate credit ratings: Selection on size or productivity? International Review of Economics & Finance, 49, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbi, M. (2012). On the risk-neutral value of debt tax shields. Applied Financial Economics, 22(3), 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellovary, J. L., Giacomino, D. E., & Akers, M. D. (2007). A review of bankruptcy prediction studies: 1930 to present. Journal of Financial Education, 33, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bessembinder, H., Chen, T.-F., Choi, G., & Wei, K. C. J. (2019). Do global stocks outperform US Treasury bills? SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, S. T., & Shumway, T. (2008). Forecasting default with the Merton distance to default model. The Review of Financial Studies, 21(3), 1339–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, N. T., & Hasan, A. (2013). Impact of firm specific factors on profitability of firms in food sector. Open Journal of Accounting, 2(2), 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, F., & Scholes, M. (1973). The pricing of options and corporate liabilities. Journal of Political Economy, 81(3), 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutchaktchiev, V. (2017). On the use of macroeconomic factors to forecast probability of default (November 1, 2017). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3082749 (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Carling, K., Jacobson, T., Lindé, J., & Roszbach, K. (2007). Corporate credit risk modeling and the macroeconomy. Journal of Banking & Finance, 31(3), 845–868. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, V. (2013). Macroeconomic determinants of the credit risk in the banking system: The case of the GIPSI. Economic Modelling, 31, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathcart, L., Dufour, A., Rossi, L., & Varotto, S. (2020). The differential impact of leverage on the default risk of small and large firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 60, 101541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaibi, H., & Ftiti, Z. (2015). Credit risk determinants: Evidence from a cross-country study. Research in International Business and Finance, 33, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrapala, P., & Knápková, A. (2013). Firm-specific factors and financial performance of firms in the Czech Republic. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 61(7), 2183–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G., & Meng, B. (2019). Debt rating model based on default identification. Management Decision, 57(9), 2239–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T. C., & Chiang, J. J. (1996). Dynamic analysis of stock return volatility in an integrated international capital market. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 6(1), 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., & Richardson, M. (2016). The volatility of a firm’s assets and the leverage effect. Journal of Financial Economics, 121(2), 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin-Dufresne, P., Goldstein, R. S., & Martin, J. S. (2001). The determinants of credit spread changes. The Journal of Finance, 56(6), 2177–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, P., & Bohn, J. (2003). Modeling default risk: Modeling methodology. KMV Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, C., Li, Z., & Yang, C. (2018). Measuring firm size in empirical corporate finance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 86, 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Dar, A. A., & Qadir, S. (2019). Distance to default and probability of default: An experimental study. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirhan, H., & Sayilgan, G. (2021). Predicting the financial failures of manufacturing companies trading in the Borsa Istanbul (2007–2019). Journal of Financial Risk Management, 10(4), 416–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, D. J. (2011). Financial flexibility and corporate liquidity. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17(3), 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, P., Mayhew, S., & Stivers, C. (2006). Stock returns, implied volatility innovations, and the asymmetric volatility phenomenon. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 41(2), 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y., & Suo, W. (2003). Assessing credit quality from equity markets: Is structural model a better approach? SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J. C., Kim, B., Kim, W., & Shin, D. (2018). Default probabilities of privately held firms. Journal of Banking and Finance, 94, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J. C., Sun, J., & Wang, T. (2012). Multiperiod corporate default prediction—A forward intensity approach. Journal of Econometrics, 170(1), 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffie, D., Eckner, A., Horel, G., & Saita, L. (2009). Frailty correlated default. The Journal of Finance, 64(5), 2089–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, D., Kocagil, A., & Stein, R. (2004). The Moody’s KMV RiskCalc v3. 1 Model: Next-generation technology for predicting private firm credit risk. Moody’s KMV. [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein, Z., Setty, O., & Weiss, D. (2018). Financial risk and unemployment. International Economic Review, 60(2), 475–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldomiaty, T., Mostafa, W., & Attia, O. (2016). Empiricism of corporate debt safe buffer. Advances in Financial Planning & Forecasting, 7, 27–75. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J., Marshall, B. R., Nguyen, N. H., & Visaltanachoti, N. (2021). Do stocks outperform treasury bills in international markets. Finance Research Letters, 40, 101710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmen, T. E. (2004). Default Greeks under an objective probability measure. In Norwegian School of Science and Technology Management working paper. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:14494007 (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Feynman, R. (2013). The Brownian movement (Vol. 1). California Institute of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Figlewski, S., Frydman, H., & Liang, W. (2012). Modeling the effect of macroeconomic factors on corporate default and credit rating transitions. International Review of Economics & Finance, 21(1), 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M., & Jensen, B. A. (2024). The tax shield increases the interest rate. Journal of Banking and Finance, 161(c), 107096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, N. (2004). Do shareholders really prefer risky projects? Australian Journal of Management, 29(2), 147–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhart, C. A. E., Tsomocos, D. P., & Wang, X. (2023). Bank credit, inflation, and default risks over an infinite horizon. Journal of Financial Stability, 67, 101131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Z., & Siddiqui, M. A. (2023). Firm specific and macroeconomic determinants of probability of default: A case of Pakistani Non-Financial Sector. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 18(2), 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D., Qi, H., & Xie, Y. A. (2017). Effective income tax rates by structural models of bankruptcy. International Journal of Business, Accounting and Finance, 11(1), 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, G. S., & Wernerfelt, B. (1989). Determinants of firm performance: The relative importance of economic and organizational factors. Strategic Management Journal, 10(5), 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. M., & Habib, A. (2017). Firm life cycle and idiosyncratic volatility. International Review of Financial Analysis, 50, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, R., & Senbet, L. (1978). The insignificance of bankruptcy costs in the theory of optimal capital structure. Journal of Finance, 33(2), 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46(6), 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J. A., & Taylor, W. E. (1981). Panel data and unobservable individual effects. Econometrica, 49(6), 1377–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss, E. S., John, K., Li, B., Ponticelli, J., & Wang, W. (2023). Default and bankruptcy resolution in China. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 15(1), 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-S., & Wu, C.-H. (2020). Extended black and Scholes model under bankruptcy risk. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications, 482, 123564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibe, O. C. (2013). Markov processes for stochastic modeling. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M. S., Alam, M. S., Hasan, S. B., & Mollah, S. (2022). Firm-level political risk and distance-to-default. Journal of Financial Stability, 63, 101082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, S., Bizel, G., Jagannathan, S. K., & Gollapalli, S. S. C. (2024). A comprehensive approach to bankruptcy risk evaluation in the financial industry. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T., Lindé, J., & Roszbach, K. (2013). Firm default and aggregate fluctuations. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11(4), 945–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubik, P. (2007). Macroeconomic environment and credit risk. Czech Journal of Economics and Finance (Finance a uver), 57(1–2), 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jermias, J., & Yigit, F. (2019). Factors affecting leverage during a financial crisis: Evidence from Turkey. Borsa Istanbul Review, 19(2), 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, C., & Lando, D. (2015). Robustness of distance-to-default. Journal of Banking & Finance, 50(1), 493–505. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, G., & Mencia, J. (2009). Modelling the distribution of credit losses with observable and latent factors. Journal of Empirical Finance, 16(2), 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jónsson, J. G., & Fridson, M. S. (1996). Forecasting default rates on high-yield bonds. The Journal of Fixed Income, 6(1), 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalak, I. E., & Hudson, R. (2016). The effect of size on the failure probabilities of SMEs: An empirical study on the US market using discrete hazard model. International Review of Financial Analysis, 43, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavussanos, M. G., & Tsouknidis, D. A. (2016). Default risk drivers in shipping bank loans. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 94, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayo, E. K., & Kimura, H. (2011). Hierarchical determinants of capital structure. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(2), 358–371. [Google Scholar]

- Kealhofer, S. (2003a). Quantifying credit risk II: Debt valuation. Financial Analysts Journal, 59(3), 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kealhofer, S. (2003b). Quantifying credit risk II: Default prediction. Financial Analysts Journal, 59(1), 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kealhofer, S., & Kurbat, M. (2001). The default prediction power of the Merton approach, relative to debt ratings and accounting variables. KMV LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Kemsley, D., & Nissim, D. (2002). Valuation of the debt tax shield. The Journal of Finance, 57(5), 2045–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoja, L., Chipulu, M., & Jayasekera, R. (2019). Analysis of financial distress cross countries: Using macroeconomic, industrial indicators and accounting data. International Review of Financial Analysis, 66, 101379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, M., & Wachter, J. A. (2017). Risk, unemployment, and the stock market: A rare-event-based explanation of labor market volatility. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliestik, T., Misankova, M., & Kocisova, K. (2015). Calculation of distance to default. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollar, B. (2014). Credit value at risk and options of its measurement. 2nd international conference on economics and social science (ICESS 2014), information engineering research institute. Advances in Education Research, 61, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A., Jamadar, I., Goel, R., Petluri, R. C., & Feng, W. (2024). Mathematically forecasting stock prices with geometric Brownian motion. North Carolina Journal of Mathematics and Statistics, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntluru, S., Muppani, V. R., & Khan, M. A. A. (2008). Financial performance of foreign and domestic owned companies in India. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business, 9(1), 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lando, D., & Nielsen, M. S. (2010). Correlation in corporate defaults: Contagion or conditional independence? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 19(3), 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurin, M., & Martynenko, O. (2009). The influence of macroeconomic factors on the probability of default. Lund University Libraries, Department of Economics. Available online: https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=1486524&fileOId=1647104 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Lee, C.-Y. (2014). The effects of firm specific factors and macroeconomics on profitability of property-liability insurance industry in Taiwan. Journal of Business & Management (COES&RJ-JBM), 2(1), 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Leland, H. E. (2004). Predictions of default probabilities in structural models of debt. Journal of Investment Management, 2(2), 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Leland, H. E., & Toft, K. B. (1996). Optimal capital structure, endogenous bankruptcy, and the term structure of credit spreads. The Journal of Finance, 51(3), 987–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozinskaia, A., Merikas, A., Merika, A., & Penikas, H. (2017). Determinants of the probability of default: The case of the internationally listed shipping corporations. Maritime Policy & Management, 44(7), 837–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, P. (1982). The choice between equity and debt: An empirical study. Journal of Finance, 37, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R. C. (1974). On the pricing of corporate debt: The risk structure of interest rates. The Journal of Finance, 29(2), 449–470. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, S., & Purnanandam, A. (2019). Banks’ risk dynamics and distance to default. The Review of Financial Studies, 33(6), 2421–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z., Jiang, M., & Zhan, W. (2023). Default prediction with industry-specific default heterogeneity indicators based on the forward intensity model. Axioms, 12, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkusu, M. (2011). Nonperforming loans and macro financial vulnerabilities in advanced economies. Working paper No. 11-161. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlson, J. A. (1980). Financial ratios and the probabilistic prediction of bankruptcy. Journal of Accounting Research, 18(1), 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y. (2008). Macroeconomic factors and probability of default. European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences, 13, 192–215. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, J. B. (1969). Tests for specification errors in classical linear least squares regression analysis. Journal of Royal Statistical Society B, 31(2), 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K., & Clinton, V. (2016). Simulating stock prices using geometric Brownian motion: Evidence from Australian companies. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 10(3), 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ricca, B., Ferrara, M., & Loprevite, S. (2023). Searching for an effective accounting-based score of firm performance: A comparative study between different synthesis techniques. Quality & Quantity, 57, 3575–3602. [Google Scholar]

- Sapra, S. (2005). A regression error specification test (RESET) for generalized linear models. Economics Bulletin, 3(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sima-Grigore, A., & Sima, A. (2011). Distance to default estimates for Romanian listed companies. The Review of Finance and Banking, 3(2), 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, D., & Rolwes, F. (2009). Macroeconomic default modeling and stress testing. International Journal of Central Banking, 5(3), 177–204. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G., & Singla, R. (2021). Default risk and stock returns: Evidence from Indian corporate sector. Vision, 27(3), 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A. (2024). Daily and weekly geometric Brownian motion stock index forecasts. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(10), 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenbäck, T. (2013). Corporate default prediction with financial ratios and macroeconomic variables [Master Thesis, Department of Economics, Aalto University, School of Business]. Available online: https://epub.lib.aalto.fi/en/ethesis/pdf/13393/hse_ethesis_13393.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Stretcher, R., & Johnson, S. (2011). Capital structure: Professional management guidance. Managerial Finance, 37(8), 788–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thursby, J. G., & Schmidt, P. (1977). Some properties of tests for specification error in a linear regression. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 72(359), 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thursby, J. G., & Schmidt, P. (1979). Alternative specification error tests: A comparative study. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(365), 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traczynski, J. (2017). Firm default prediction: A Bayesian model-averaging approach. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 52(3), 1211–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasicek, O. A. (1984). Credit valuation. KMV Corporation. Available online: http://www.ressources-actuarielles.net/EXT/ISFA/1226.nsf/0/c181fb77ee99d464c125757a00505078/$FILE/Credit_Valuation.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Vassalou, M., & Xing, Y. (2004). Default risk in equity returns. The Journal of Finance (New York. Print), 59(2), 831–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virolainen, K. (2004). Macro stress testing with a macroeconomic credit risk model for Finland. Bank of Finland Discussion Papers, No. 18/2004. Bank of Finland. ISBN 952-462-154-1. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:fi:bof-20140807436 (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Vu, V. T., Do, N., Dang, H. N., & Nguyen, T. (2019). Profitability and the distance to default: Evidence from Vietnam securities market. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 6, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, E. J., & Ryan, J. (1997). Agency and tax explanations of security issuance decisions. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 24, 943–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J. B. (1977). Bankruptcy costs: Some evidence. The Journal of Finance, 32(2), 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J. (2007). Testing for error correction in panel data. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 69(6), 709–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. W., & Turnbull, S. M. (1974). The probability of bankruptcy for American industrial firms. Working Paper IFA-4-74. London Graduate School of Business Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2015). Introductory econometrics—A modern approach. International Student Edition. Thomson South-Western. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, K., Luo, D., & Liu, L. (2023). Macroeconomic conditions, corporate default, and default clustering. Economic Modelling, 118, 106079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Yang, Z., & Xiao, Y. (2022). Forecasting corporate default risk in China. International Journal of Forecasting, 38(3), 1054–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Measurement | Reference | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Debt-to-Equity ratio | Total debt/total equity. | Marsh (1982), Auerbach (1985), Bhutta and Hasan (2013), Lee (2014), Chandrapala and Knápková (2013), Lozinskaia et al. (2017). | There is a negative relation between “Debt to Equity” and the distance-to-default. |

| Effective Corporate Tax Rate | Tax expenses/taxable income. | Walsh and Ryan (1997), Alworth and Arachi (2003), Han et al. (2017). | There is a negative relation between “Effective tax rate” and the distance-to-default. |

| Bankruptcy Costs | Bankruptcy Costs = fixed charges − earnings before income and tax)/(). | White and Turnbull (1974), Warner (1977), Gong (2004). | There is a negative relation between bankruptcy costs and the distance-to-default. |

| Compound Growth Rate of Free Cash Flow (FCF) | FCF = EBIT + depreciation − tax − change in net fixed assets − change in net working capital. | Stretcher and Johnson (2011), Denis (2011). | There is a positive relation between a “Company’s Growth of free cash Flow” and the distance-to-default. |

| Size | Natural log of sales revenue. Natural log of equity market value. | Bhutta and Hasan (2013), Dang et al. (2018). | There is a positive relation between “Sales Growth” and the distance-to-default. |

| Growth of GDP | Annual compound growth of nominal GDP. | Simons and Rolwes (2009). | There is a positive relation between “Growth of GDP” and the distance-to-default. |

| Inflation Rate | Annual compound growth of CPI. | Qu (2008), Laurin and Martynenko (2009). | There is a negative relation between “Growth of inflation” and the distance-to-default. |

| Productivity Growth | Total industrial production index2. | Qu (2008), Laurin and Martynenko (2009), Figlewski et al. (2012), Boutchaktchiev (2017), Xing et al. (2023). | There is a negative relation between “percentage change in manufacturing output” and the distance-to-default. |

| % change in manufacturing output | Gross output by industry: manufacturing3. | Stenbäck (2013), Demirhan and Sayilgan (2021). | There is a negative relation between “percentage change in manufacturing output” and the distance-to-default. |

| Interest Rates | Annual T-bill rates4. | Laurin and Martynenko (2009). | There is a negative relation between interest rates and the distance-to-default. |

| Growth of Unemployment Rate | Annual compound growth of unemployment rates5. | Nkusu (2011), Castro (2013), Chaibi and Ftiti (2015). | There is a negative relation between “unemployment rate’s growth” and the distance-to-default. |

| Industry Average Retail Inventory to sales | Ratio of annual ratio of retail inventory to sales revenue6. | These variables are added by the authors to examine whether companies follow industry targets. | There is a positive relation between industry ratios and companies’ distance-to-default. |

| Industry Average Growth Sales (Retail) | Merchant wholesalers: inventories to sales ratio7. | ||

| Industry Average Growth Inventory (Wholesalers) | Merchant wholesalers inventories8. |

| Model 1: Company-Specific | Model 2: Company-Specific and Country-Specific | Mode 3: Company-Specific and Country-Specific Determinants of Stochastic DD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Debt-to-Equity | −0.0002 (−3.13) ** | −0.0081 (−3.04) ** | −0.004 (−2.95) ** |

| Effective Tax Rate | −0.008 (−0.89) | 0.0073 (1.70) * | 0.0226 (2.69) ** |

| Bankruptcy Costs | −0.0015 (−2.77) *** | −0.039 (−3.22) *** | −0.0568 (−3.81) *** |

| Growth of Free Cash Flow | −0.0072 (−3.29) ** | −0.0048 (−3.37) *** | −0.00037 (−0.165) |

| Return on Assets | −0.0051 (−2.44) *** | −0.0051 (−2.84) ** | −0.0021 (−1.093) |

| Price-to-Earnings | −0.0037 (−1.08) | −0.004 (−0.73) | −0.0061 (−0.48) |

| Size (ln Sales Revenue) | 1.050 (10.68) *** | 1.230 (9.93) *** | 1.7296 (11.99) *** |

| Size (ln Market Value) | 0.025 (9.01) *** | 0.851 (8.41) *** | 0.7052 (8.01) *** |

| Growth of GDP | −5.948 (−3.58) *** | −12.63 (−1.181) | |

| Inflation Rate | −0.018 (−1.59) | −0.008 (−0.055) | |

| Productivity Growth | 1.018 (1.20) | −4.423 (−0.306) | |

| % Change in Manufacturing Output | −0.328 (−0.011) | 2.829 (1.991) ** | |

| T-Bills | 4.678 (3.75) ** | −4.283 (−1.940) *** | |

| Growth Unemployment Rate | −0.996 (−1.87) * | 4.122 (0.2953) | |

| Industry Average Retail Inventory to sales | 84.625 (5.85) *** | 140.478 (8.61) *** | 41.38 (5.621) *** |

| Industry Average Growth Sales (Retail) | −1.170 (−6.09) *** | −1.433 (−2.39) ** | 2.391 (0.994) |

| Industry Average Growth Inventory (Wholesalers) | 3.123 (2.72) *** | 2.197 (2.29) ** | −10.168 (−0.228) |

| Type of Industry (Dummy, Binary) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 4.210 (10.36) *** | 5.378 (11.97) *** | −72.38 (−5.947) *** |

| R2 | 0.6654 | 0.8335 | 0.8732 |

| F Statistic | 24.75 *** | 31.31 *** | 22.28 *** |

| VIF (Max) | 2.8 | 4.64 | 3.70 |

| N | 7848 | 7848 | 7848 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eldomiaty, T.; Azzam, I.; El Kolaly, H.; Dabour, A.; Anwar, M.; Elshahawy, R. Determinants of Stochastic Distance-to-Default. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020091

Eldomiaty T, Azzam I, El Kolaly H, Dabour A, Anwar M, Elshahawy R. Determinants of Stochastic Distance-to-Default. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(2):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020091

Chicago/Turabian StyleEldomiaty, Tarek, Islam Azzam, Hoda El Kolaly, Ahmed Dabour, Marwa Anwar, and Rehab Elshahawy. 2025. "Determinants of Stochastic Distance-to-Default" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 2: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020091

APA StyleEldomiaty, T., Azzam, I., El Kolaly, H., Dabour, A., Anwar, M., & Elshahawy, R. (2025). Determinants of Stochastic Distance-to-Default. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(2), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020091