Abstract

This paper presents a thorough review of state-of-the-art research and literature in the field of photovoltaic tracking systems for the production of electrical energy. A review of the literature is performed mainly for the field of solar photovoltaic tracking systems, which gives this paper the necessary foundation. Solar systems can be roughly divided into three fields: the generation of thermal energy (solar collectors), the generation of electrical energy (photovoltaic systems), and the generation of electrical energy/thermal energy (hybrid systems). The development of photovoltaic systems began in the mid-19th century, followed shortly by research in the field of tracking systems. With the development of tracking systems, different types of tracking systems, drives, designs, and tracking strategies were also defined. This paper presents a comprehensive overview of photovoltaic tracking systems, as well as the latest studies that have been done in recent years. The review will be supplemented with a factual presentation of the tracking systems used at the Institute of Energy Technology of the University of Maribor.

1. Introduction

Climate change and the exponential growth of energy demand are calling for a huge expansion of renewable energy sources around the world. Currently, the installed capacity of all photovoltaic systems (PV) worldwide is greater than the sum of all other renewable energy systems, which amounted to 102.4 GW in 2018 and 125 GW in 2020 [1]. Solar energy is an inexhaustible source of energy and will play an important role in the future. However, the density of solar radiation varies from location to location and thus, the use of solar energy. The use of solar energy can be encouraged in several ways, such as monitoring or subsidies, as well as through solar systems that follow the sun’s path—called tracking solar systems. The main goal of tracking systems is to increase the energy yield, which according to previously conducted research and studies ranges between 22% and 56% compared to a fixed solar system. However, it also depends on the driving system, degree of freedom, control system, and other parameters such as weather conditions or location. The generated electrical energy from photovoltaic systems depends mainly on solar radiation reaching the photovoltaic modules, as well as the materials used [2], the temperature [3], and the inverter. The power density of solar radiation reaching the earth’s surface cannot be directly influenced, as it depends mainly on the location and the conditions in the atmosphere. However, the photovoltaic system can be oriented so that the rays fall perpendicular to the observed surface of the photovoltaic module and thus optimize the production of electrical energy. The influence of the temperature of the photovoltaic modules on the conversion efficiency is extremely important [4,5], as are the types of photovoltaic modules and their applicability [6]. In addition to the type of technology and other influences on photovoltaic modules, the efficiency of the conversion of solar radiation into electrical energy mainly depends on the impedance adjustment, which is (in other words) called the maximum power point tracking (MPPT). The optimization of electrical parameters to achieve the maximum production of electrical energy from a photovoltaic system using the MPPT algorithm is also extremely important. The photovoltaic tracking systems that follow the trajectories of the sun’s rays ensure that the power density of the solar radiation is perpendicular to the normal of the module surface. The tracking is achieved by proper control and use of the tracking system drive assembly. Photovoltaic tracking systems receive the energy of the sun’s rays directly on the photovoltaic modules and are further divided according to the number of degrees of freedom. The most common are single-axis [7] and dual-axis [8] photovoltaic tracking systems. Single-axis photovoltaic tracking systems follow the trajectories of the sun by moving around one axis, most commonly from east to west, while dual-axis photovoltaic tracking systems can move in two axes, from north to south and from east to west. Dual-axis photovoltaic tracking systems can be more precise than single-axis photovoltaic tracking systems but are more expensive because of the additional rotating axis. In some cases, investing in dual-axis photovoltaic tracking systems can be non-feasible, as their energy yield is only a few percentage points higher than that of a single-axis tracking system.

Control systems, called closed-loop [9] and open-loop [10] control tracking systems, are mostly used to actuate the drive assemblies of a single-axis or dual-axis photovoltaic tracking system. The main difference between open-loop and closed-loop tracking systems is that the former tracking system uses a photosensor (light-dependent resistor (LDR)) for its operation, which sends a signal to the control unit, while the latter system uses an algorithm loaded in the processor of the controller. The combination of both closed-loop and open-loop tracking systems is the so-called hybrid control tracking system. An example of a dual-axis tracking system with a hybrid tracking system is presented in [11]. In addition to ensuring the required accuracy of the tracking system, it is also necessary to minimize electrical losses caused by the movement of the drive assembly. The researchers in [12] present the optimal inclination and azimuth angle for a fixed photovoltaic system, while the researchers in [13] deal with the best solution for the photovoltaic tracking system. Since active photovoltaic tracking systems use electrical energy for their operation, it is necessary to optimize their consumption. Similarly, the researchers in [14] present the optimal tracking of the azimuth tracking system by the trajectory of the sun, with the aim of maximizing the electrical energy production of a PV system with a minimum number of shifts. Optimization is determined for one day, by comparing the characteristics obtained at different numbers of movements. The results should provide an answer to the question of when and by how many degrees it would be necessary to change the azimuth angle in order to maximize electrical energy production.

Several authors deal with the design [15], simulation [16], and optimization [17] of tracking systems, using dynamic (multi-body) models of tracking systems together with dynamic models of powertrains and controls, otherwise called virtual prototypes [18]. In doing so, they use known models for the calculation of solar radiation, while the tools are used for the design and continuous control of single-axis tracking systems.

Photovoltaic tracking systems represent higher investment costs, but at the same time require more knowledge in management and maintenance compared to the classic fixed photovoltaic system. To this end, so-called virtual laboratories have been established, which primarily reduce the cost of learning equipment and reduce the risk of damage to the system during teaching/learning process. According to certain studies, learning in a new virtual environment is also more effective [19].

Many different papers [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] have been written in recent years reviewing the literature in the field of tracking PV systems, covering everything from the classification of photovoltaic tracking systems, the use of individual components, to the MPPT algorithm. A significant contribution of this paper is a comprehensive review of scientific articles and reports by 2020 and a review of important specifications of commercial systems used for market purposes. The paper is divided into seven chapters, namely: introduction, solar systems (basic division between photovoltaic, solar thermal, and photovoltaic/thermal systems), classification based on the driving system (passive and active tracking systems), classification based on degree of freedom (single and dual-axis tracking systems—comprehensive review), classification based on control system (open- and closed-loop tracking systems—comprehensive review), commercial photovoltaic tracking systems for electricity generation, and conclusion.

2. Solar Systems

Solar systems use solar energy (or electromagnetic wave energy of the sun’s rays) to produce electrical and/or thermal energy [30]. In terms of energy production, we divide the solar systems into:

- Direct generation of electrical energy: photovoltaic modules,

- Direct generation of heat: solar collectors,

- Direct generation of electrical energy and indirect generation of thermal energy: photovoltaic/thermal (PV/T) hybrid collectors.

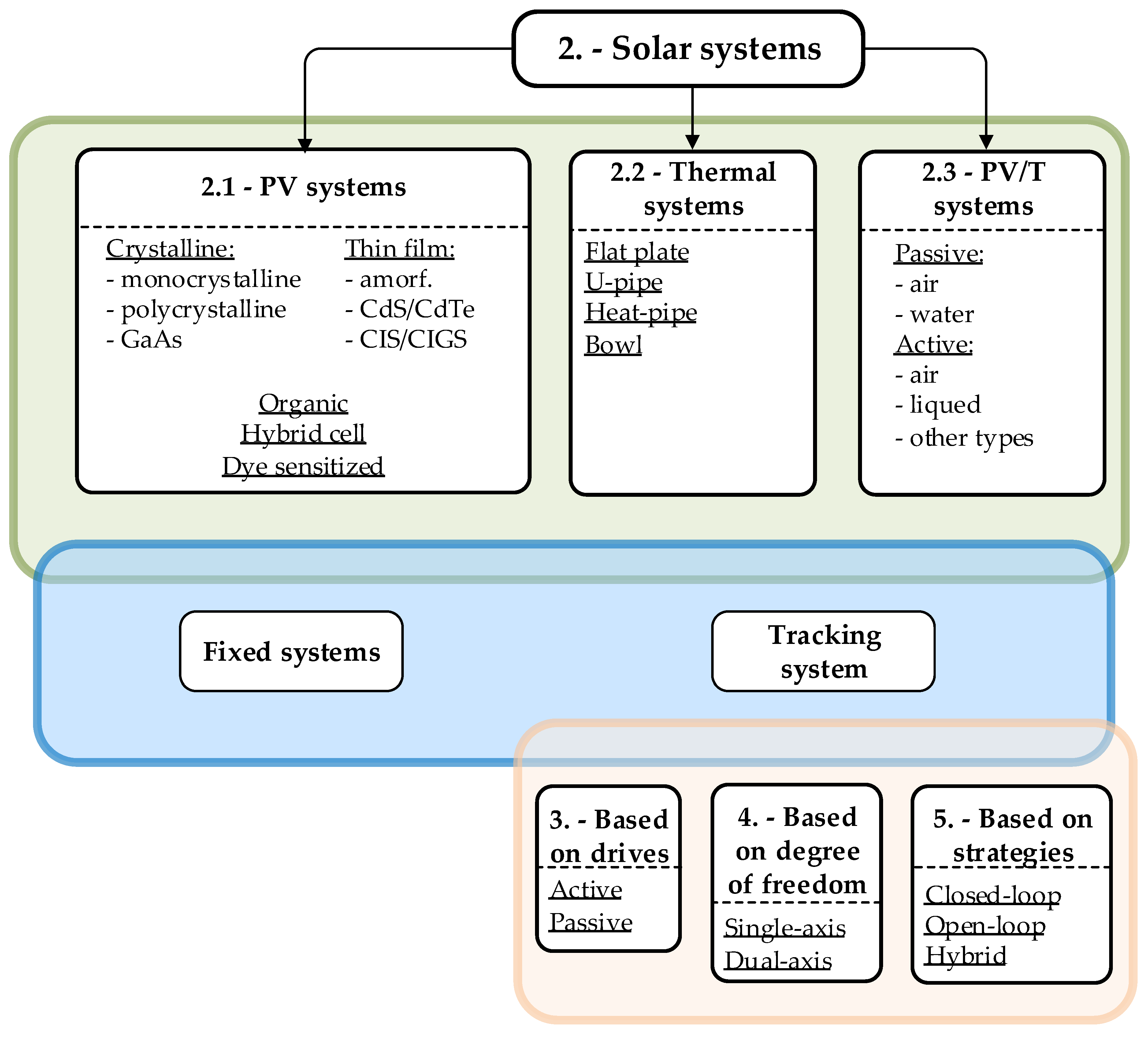

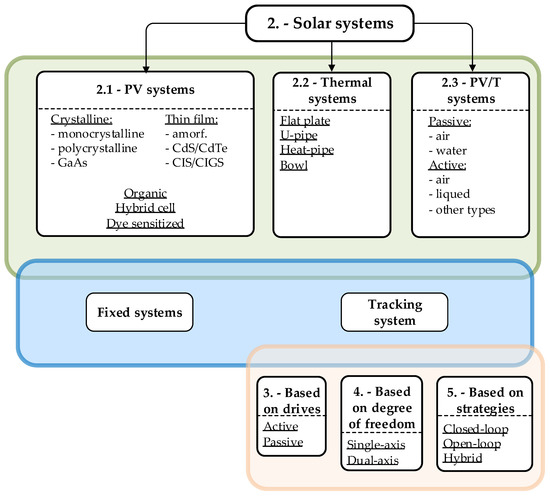

Figure 1 presents a classification of the use of solar systems using a particular load-bearing construction, which can be used as a construction for the PV system at different slopes and orientations, or can be used to improve the production of electrical and or thermal energy. Therefore, the load-bearing constructions can be divided into:

Figure 1.

Classification of solar systems.

- Fixed systems, and

- Tracking systems.

2.1. Photovoltaic Systems

The terminology described by IEC 61836 (Solar Photovoltaic Energy Systems—Conditions and Symbols) [31] defines photovoltaic systems as systems that convert the visible portion of the solar radiation spectrum directly into electrical energy. The basic building block of each photovoltaic system is a solar cell that generates electrical power when exposed to solar radiation (IEC 60904-3 [32]). Several interconnected solar cells form a module that represents the smallest environmentally protected unit (IEC 60904-3 [32] in IEC 61277 [33]). A group of electrically and mechanically interconnected modules that form an electrically and mechanically complete unit is called a panel (IEC 61277 [33]), intended as a field installation unit. The field is a mechanically complete set of panels together with the load-bearing construction, but without the foundations, tracking mechanisms, thermal control elements, and other similar elements forming the unit for the production of electrical energy in a direct current system (IEC 61277 [33]). When the field of panes for the production of electrical energy in the DC system is added a DC/DC converter for impedance adjustment, a DC/AC inverter for converting the DC electrical quantities into AC electrical quantities, and an algorithm for achieving the maximum power point, a solar power plant is obtained.

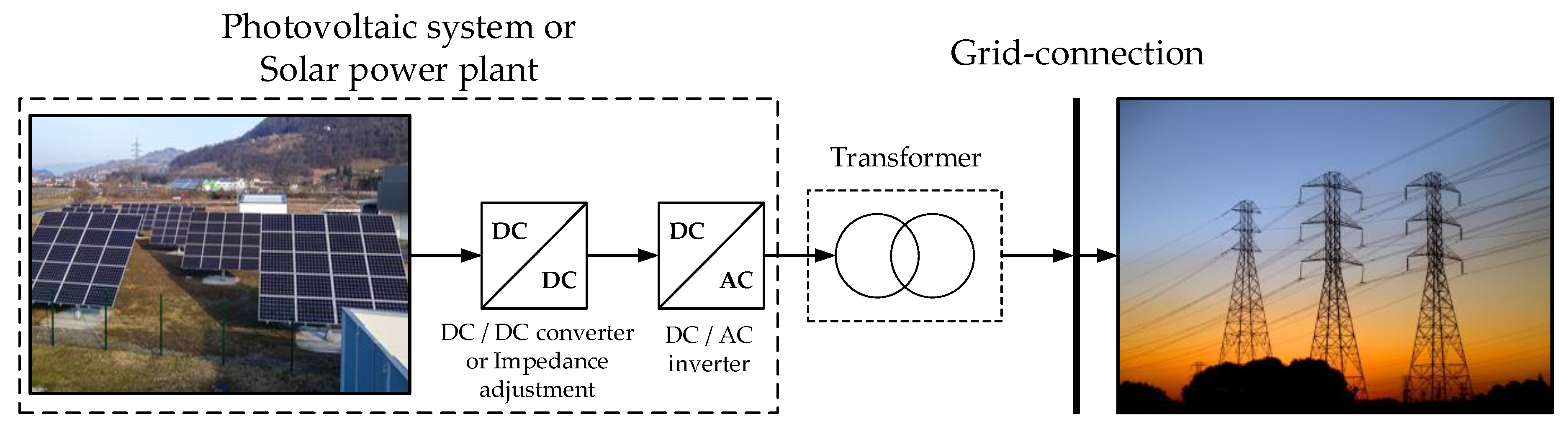

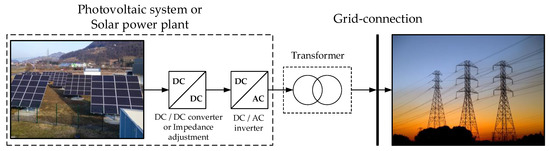

The photovoltaic system requires a consumer or an energy sink to operate. Depending on the mode of connection of the consumer, PV systems are separated into PV systems that are not intended for parallel operation with the public electricity grid and PV systems that are connected to the public electricity grid. Photovoltaic systems that are not intended for parallel operation with the public electricity grid are often used to supply electrical energy to consumers in hard-to-reach locations and to power remote communication stations or water pumps. Unlike grid-connected PV systems, these PV systems (also called stand-alone PV systems) require an adequate battery and charge regulator for flexible operation. Figure 2 shows the basic connection of the grid-connected PV system.

Figure 2.

Basic connection of the grid-connected photovoltaic (PV) system.

The main elements of each grid-connected PV system are field of panels, DC/DC converter, and DC/AC inverter. By properly connecting the panels into the field that are exposed to the sun, adequate DC voltage amplitude is achieved at the output. The DC/DC converter, on the one hand, adjusts the output DC voltage amplitude of the field of panels to the required input DC voltage amplitude of the DC/AC inverter; on the other hand, the DC/DC converter adjusts the impedance of the field of panels. In doing so, it makes sure that the field is constantly sensing such resistance that the modules in the panels operate at the maximum power point at all times. The DC/AC converter converts input DC voltage to output AC voltage using the most commonly used pulse width modulation (PWM). The output AC voltage of the DC/AC inverter is smoothed out by the output filter, which is a bandpass sieve and transmits the voltage of the basic harmonic component. The output filter can be connected directly to the grid or through a transformer, as shown in Figure 2. In the case without a DC/DC converter, the transformer takes care of the impedance adjustment.

The electrical energy generated by PV systems depends mainly on the available solar radiation reaching the PV modules. Tracking systems ensure that the sun’s rays fall perpendicular on the active surface of the PV module. The efficiency of the conversion of solar energy into electrical energy η is defined as (1) and is the ratio between the electrical energy generated by PV systems Pel and the product of the active surface of the field of panels A and the power density of the solar radiation G.

ηPV,m+DC/AC is the overall efficiency of the conversion of solar energy into electrical energy (a combination of the efficiency of PV modules and efficiency of DC/AC inverter) depending on the intensity of solar radiation G, the temperature of PV modules T, and air mass AM.

The efficiency of the conversion of solar energy into electrical energy depends mainly on the type and quality of PV modules, temperature, connections between panels, impedance adjustment, DC/DC converter, and DC/AC inverter. There are two ways to increase the density of the solar radiation that reaches the surface of the PV modules. The first is to properly select absorbent materials that absorb as much solar radiation as possible—concentrating mirrors (CPV)—(see Figure 3). The second is to increase the density of solar radiation by means of a tracking system.

Figure 3.

Concentrating PV system in municipality Pivka (Elektro Primorska d.d., Distribution unit Sežana, supervision Pivka - Electricity distribution company).

2.2. Solar Thermal Systems

According to technological development and research, solar thermal collectors can be divided into four different generations:

The first generation includes flat-plate solar collectors, which are still the most numerous type of solar collectors, usually made up of copper or aluminum tubes covered with an absorber plate. Flat-panel solar collectors are relatively effective if climatic conditions reach at least 18 °C with high levels of sunlight. Therefore, they are generally better suited for locations with high amounts of solar radiation throughout the year. Because of their design, flat-plate solar collectors are less efficient in heat management compared to other types of collectors. The problem arises in the colder periods without sufficient amounts of solar radiation. Furthermore, the installation of flat solar panels is more difficult than the newer generation ones. Diez et al. [34] performed the modelling of a flat-plate solar collector at different working fluid flow rates, using artificial neural networks (ANN). Based on the obtained results, the author suggests that future research studies should include ANN for modelling other parameters of the solar collectors, or even the complete solar system. Tong et al. [35] discovered that the use of Al2O3 nanofluids could improve the thermal efficiency of flat-plate solar collectors by at least 20%, compared to water.

The second generation includes U-tube solar collectors, which are easy to manufacture, and their efficiency is higher than flat-plate collectors, regardless of the season. A U-tube solar collector is designed on the basis of a copper tube, through which solar fluid flows into glass tubes connected in series. Kaya et al. [36] present an experimental study of thermal performance for U-tube solar collectors using ZnO/ethylene glycol-pure water nanofluids as the working fluid. The nanofluids were prepared for 1.0 vol.%, 2.0 vol.%, 3.0 vol.%, and 4.0 vol.% of volume concentration; the highest thermal efficiency was obtained using 3.0 vol.%. Kim et al. [37] discovered that the efficiency was higher at 1.0 vol.% of Al2O3 nanofluids than with 1.5 vol.%. It can be seen that the thermal efficiency of solar collectors using nanofluids is not proportional.

The third generation includes heat-pipe solar collectors (HPSC) with double-layer glass tubes. Similar to U-tube solar collectors, they are easy to manufacture, but the received solar energy is decreased because of double-layer glass tubes that surround the absorber. Shafieian et al. [38] present a review of the latest development, progress, and applications of HPSC. The study covers the area of working fluids, mathematical modelling, facade-based solar water heating systems, energy efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and future trends. Jayanthi et al. [39] performed an experimental case on HPSC using water and R134a as working fluids. The results show an increase in thermal efficiency of up to 37.37% by using the R134a instead of water. As presented for flat-plate and U-tube solar collectors, nanofluids play an important role in increasing thermal efficiency and other parameters of solar collectors. Dehaj et al. [40] performed an experimental study using water and MgO nanofluids as working fluids. Prediction methods are also used in HPSC applications. Therefore, Shafieian et al. [41] present an analysis of different data-based and conventional theoretical methods for modelling thermal solar collectors. The results show that the ANN method has proven to be the most accurate method for predicting the effectiveness of HPSC.

The latest generation of solar collectors is frost resistant, highly efficient in all weather conditions, with low thermal inertia, with heat pipe operation and with one thick layer of glass around all active collector parts; this means that the temperature of the heating fluid rises very quickly, which allows the collector to utilize the heat even at extremely short sunlight intervals. A similar solar collector is represented by Gao et al. [42] with an oscillating heat-pipe collector and flat-plate structure. This type of solar collectors overcome the poor pressure resistance of conventional solar collectors, low efficiency, and high startup temperature.

2.3. Photovoltaic/Thermal Systems

Higher operating temperatures of solar cells also cause the more rapid degradation of electrical properties. Lower operating temperatures, therefore, minimize the degradation of electrical properties of the solar cells, which are achieved by an adequate discharge of waste heat from the solar cell’s surface. The cells are cooled by exposing the surface to a cooling medium (usually water or air) which, via a heat exchanger, absorbs the waste heat of the solar cell, thereby reducing the temperature of the solar cell. Thus, the waste heat can be utilized, for example, in low-temperature heating systems. These types of systems that simultaneously produce electrical and thermal energy are called photovoltaic/thermal (PV/T) hybrid systems [43]. The advantage of PV/T modules is the significantly higher total efficiency (electrical and thermal) of converting solar energy into useful energy on a smaller surface than in the case of a standalone PV module or solar collector. PV/T modules can be divided based on the module type (design of heat exchanger, flat-plate, or concentrated PV/T modules), working fluid type (air, water, nanoparticles), or by PV material types (silicon, non-silicon).

Many methods and techniques are known for discharging waste heat from the surface of photovoltaic modules, which differ mainly according to the selected type of cooling medium [44] (air, water, or nanoparticles) and depending on whether additional energy is used for cooling, fan, coolant pump, etc.,) or not (using only natural physical laws and phenomena). Therefore, we can divide the cooling techniques of PVT modules into:

- passive cooling techniques, and

- active cooling techniques.

The most optimal cooling technique depends on many factors, including the type of photovoltaic cells or the topology of the photovoltaic modules and the photovoltaic system as such, as well as the geographical location and weather conditions to which the photovoltaic system is exposed.

3. Classification Based on the Driving System

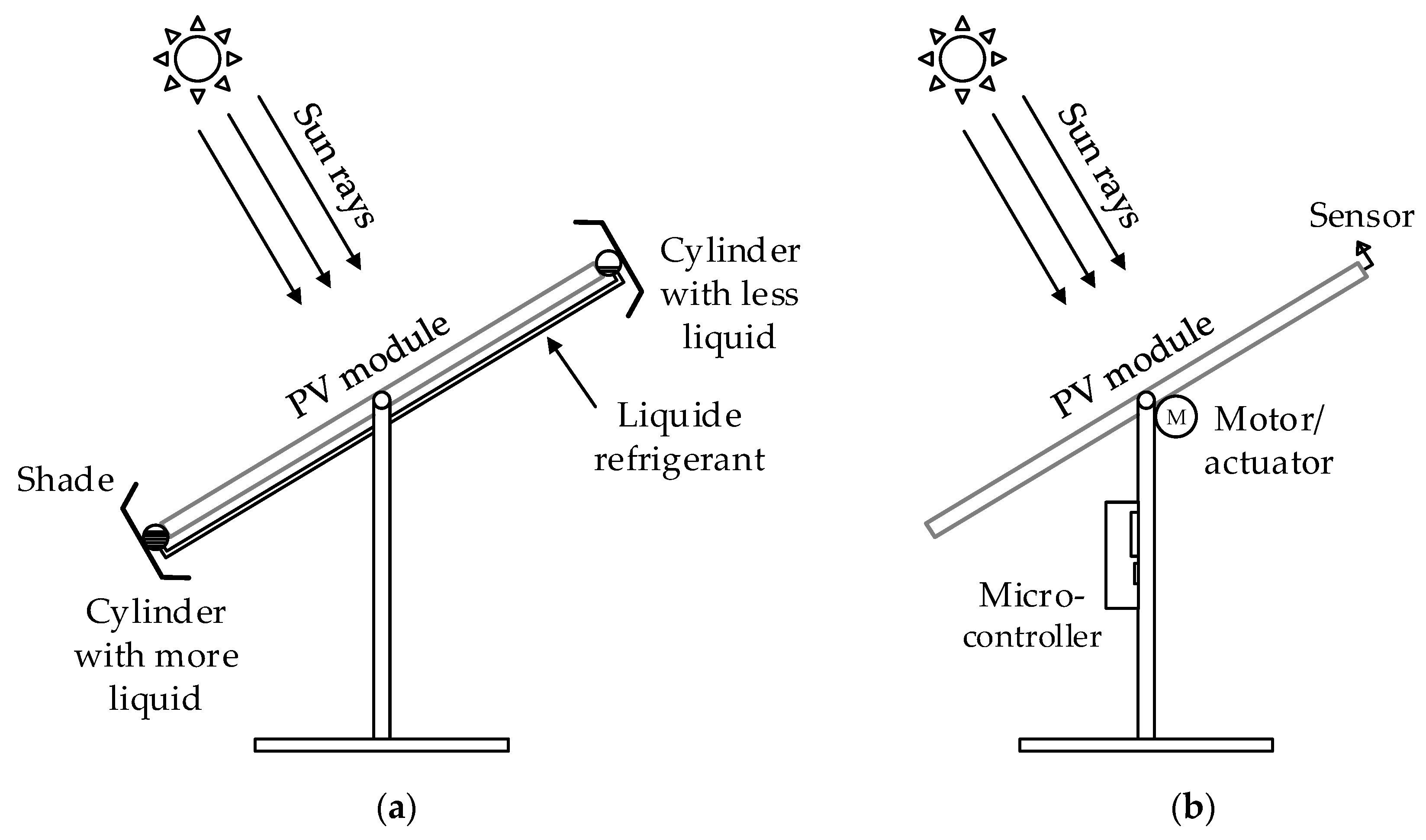

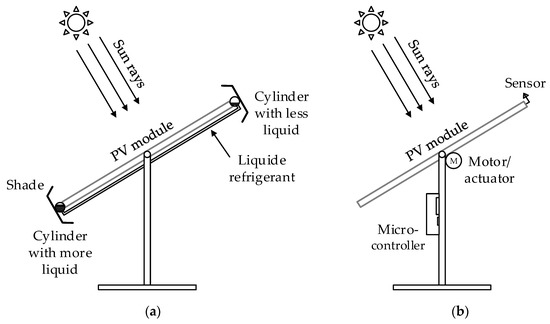

The first and the most common classification of the tracking system is based on their driving system, which can be divided into active and passive tracking systems. Passive tracking systems use the pressure difference of special liquids or gases with a low boiling point or springs from material with formed memory to move the axes of the tracking system. The pressure difference is created by the thermal differences of the shaded and illuminated sides of the tracking system. The tracking system moves until the pressure difference is in balance, which allows stretching and thus tracking in clear weather. Passive systems are used very rarely and do not need additional power supply to operate. Such systems are not suitable for demanding applications, as they are not sufficiently precise, but they are suitable for smaller individual systems. Sánchez et al. [45] present the design and construction of a dual-axis passive solar tracker. A proposed solar tracker that has two degrees of freedom, one used for continuous tracking of the sun and the other used to adjust the solar tracker manually based on seasonal changes. The accuracy of a solar tracker is relatively low, while the price of the solar tracker is below the market price of any commercial solar tracker. Clifford et al. [46] present the design of a novel passive solar tracker that is controlled by a viscous damper and activated by aluminum/steel bimetallic strips. Modelling results show an increase of efficiency by 23% compared to fixed PV systems, and excellent agreement between simulation and experimental results.

Active systems are those that use electrical drives and mechanical assemblies to operate. The main components are a microprocessor, an electric motor, gearboxes, and sensors. Active tracking systems are further divided based on control drives, namely closed-loop, open-loop, and hybrid tracking systems. In addition to the closed-loop and open-loop tracking system, active systems are also divided into intelligent control systems, microprocessor control systems, and sensor-based control systems. Intelligent control systems use artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, fuzzy logic, or neural network algorithms to control tracking systems. Microprocessor control systems use PIC and digital signal microcontrollers, while sensor-based control systems use electro-optical sensors and light-dependent resistors (LDRs). A combination of microcontroller and sensor-based control systems are very often used for control of the PV tracking systems. Only closed-loop, open-loop, and hybrid systems are described in more detail in the paper, but the descriptions of various studies also mention the method of control they use (intelligent, microcontroller or sensor-based control system). Figure 4 shows the main components of the passive and active tracking systems.

Figure 4.

Driving system: (a) passive tracking system and (b) active tracking system.

4. Classification Based on Degree of Freedom

Photovoltaic systems are structurally assembled for their operation and can be classified based on the number of directions for individual movement, called the degree of freedom. They are divided into:

- Fixed PV systems;

- Tracking PV systems;

- Single-axis tracking PV systems;

- Dual-axis tracking PV systems.

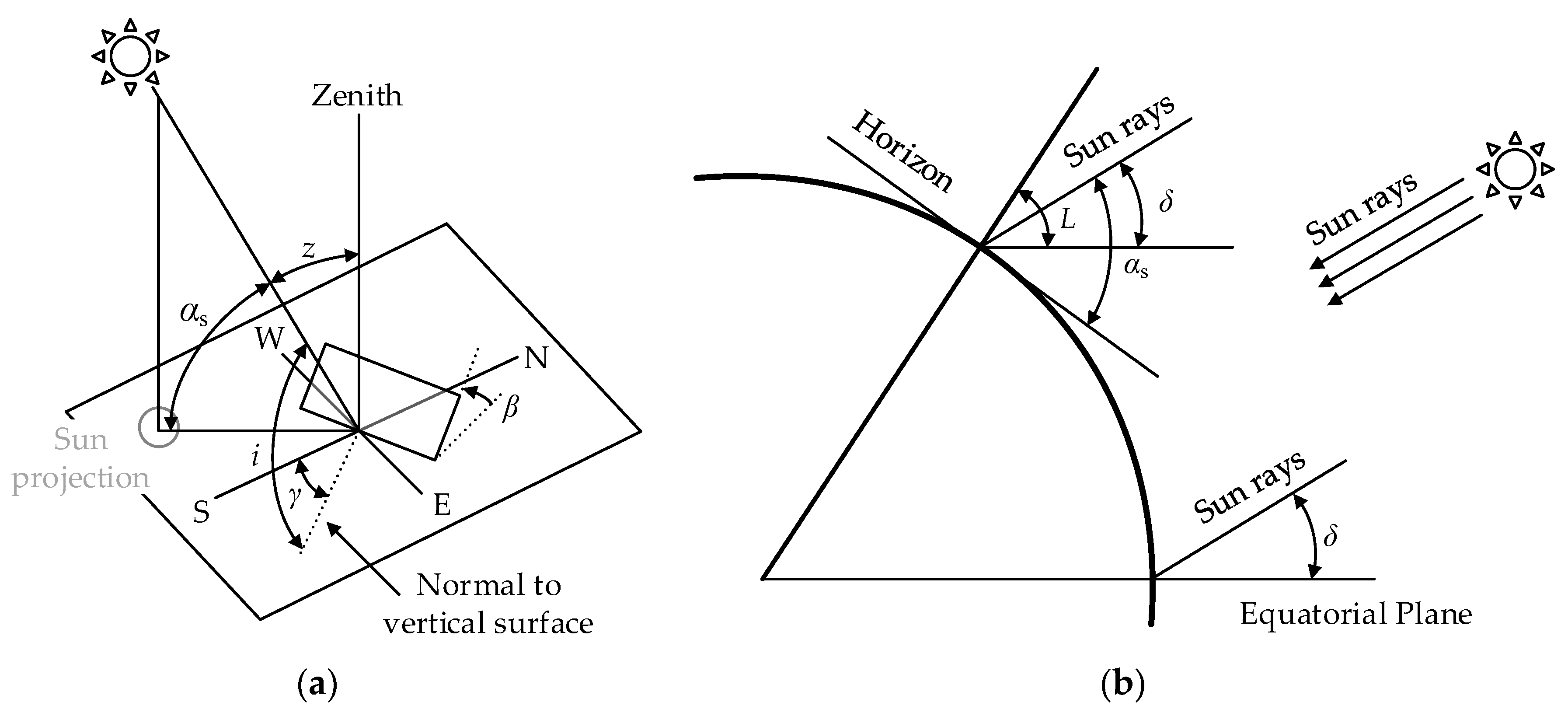

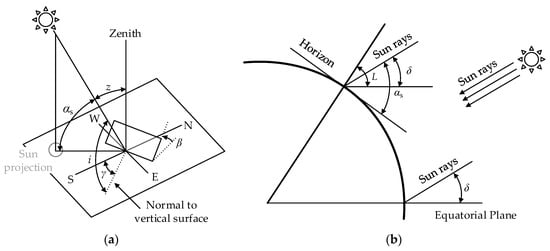

Their function is not only to attach and protect but also to determine the appropriate inclination and azimuth angle, thus increasing the yield of available solar energy that falls on the receiving surface. Thus, fixed systems are most often oriented to the south and are inclined at a certain angle (depending on longitude and latitude). Fixed PV systems represent the most common use of PV systems and can be mounted directly on the roof of buildings (at the same slope as the roof of the building). As a mathematical basis for the operation of a single-axis [47,48,49] and dual-axis [8,50] photovoltaic tracking system, the angles presented below are of key importance for the movement of the axis of the tracking system. The most important are the following angles, which are also shown in Figure 5: zenith angle z, altitude angle αs, declination angle δ, angle of incident i, latitude L, azimuth angle γ, and inclination angle β. The relations between the mentioned angles are described in more detail in [51].

Figure 5.

Description of angles—(a) zenith angle z, angle of incident i, inclination angle β, and azimuth angle γ; (b) declination angle δ and latitude L.

4.1. Single-Axis Photovoltaic Tracking System

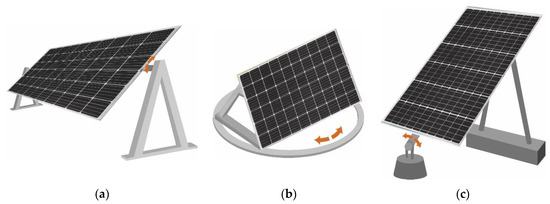

Single-axis photovoltaic tracking systems are divided into three different types. These include horizontal single-axis tracking system, vertical single-axis tracking system, and tilted single-axis tracking system.

- Horizontal single-axis tracking system (HSAT) [52,53].

The rotating axis of the HSAT is horizontal with the ground.

- Vertical single-axis tracking system (VSAT) [6,53,54].

The rotating axis of the VSAT is vertical with the ground. These tracking systems rotate from east to west during the day [53].

- Tilted single-axis tracking system (TSAT) [53].

All tracking systems with a horizontal and vertically rotating axis are considered to be tilted single-axis tracking systems. The tilt angles of tracking systems are often limited to decrease the elevated end’s height off the ground and reduce the wind profile.

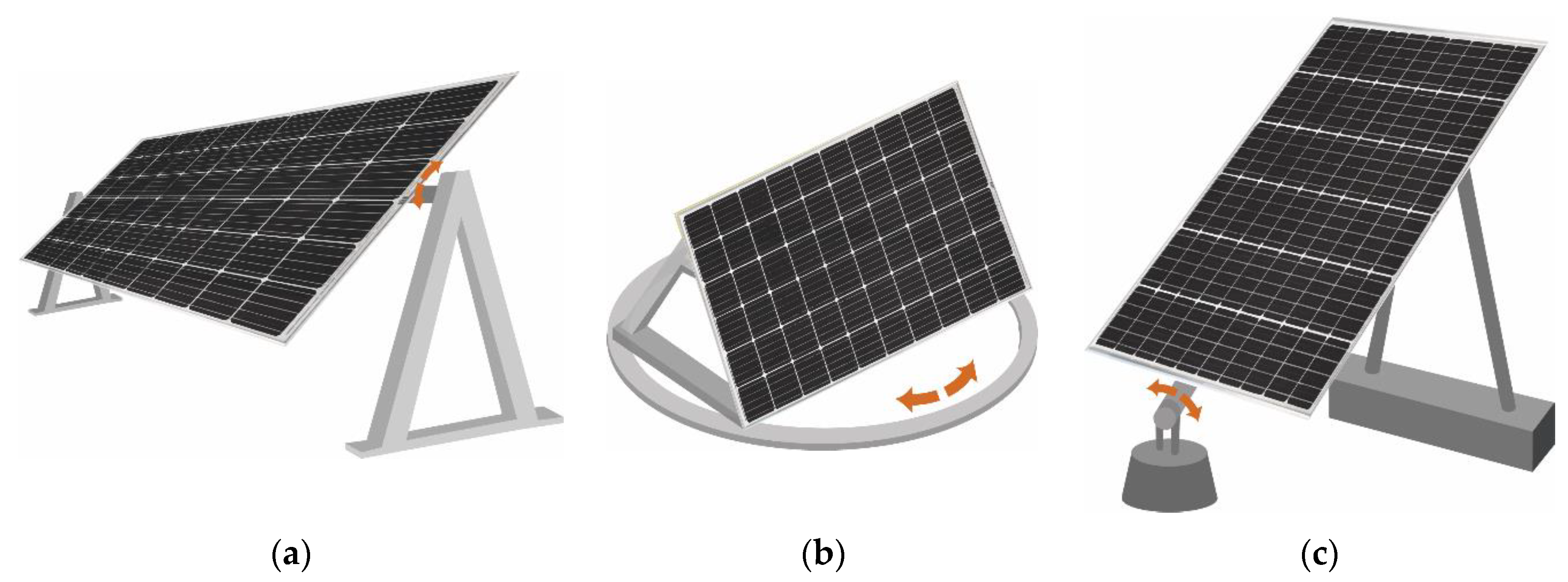

The polar-aligned single-axis tracking system (PASAT) is a unique version of the tilted single-axis tracking system. In this case, the tilt angle is equal to the latitude of the installation, which aligns the earth’s rotating axis with the rotating axis of the tracking system [53]. Figure 6 presents all three types of single-axis photovoltaic tracking systems.

Figure 6.

Single-axis photovoltaic tracking systems: (a) HSAT, (b) VSAT, and (c) TSAT.

4.2. Dual-Axis Photovoltaic Tracking System

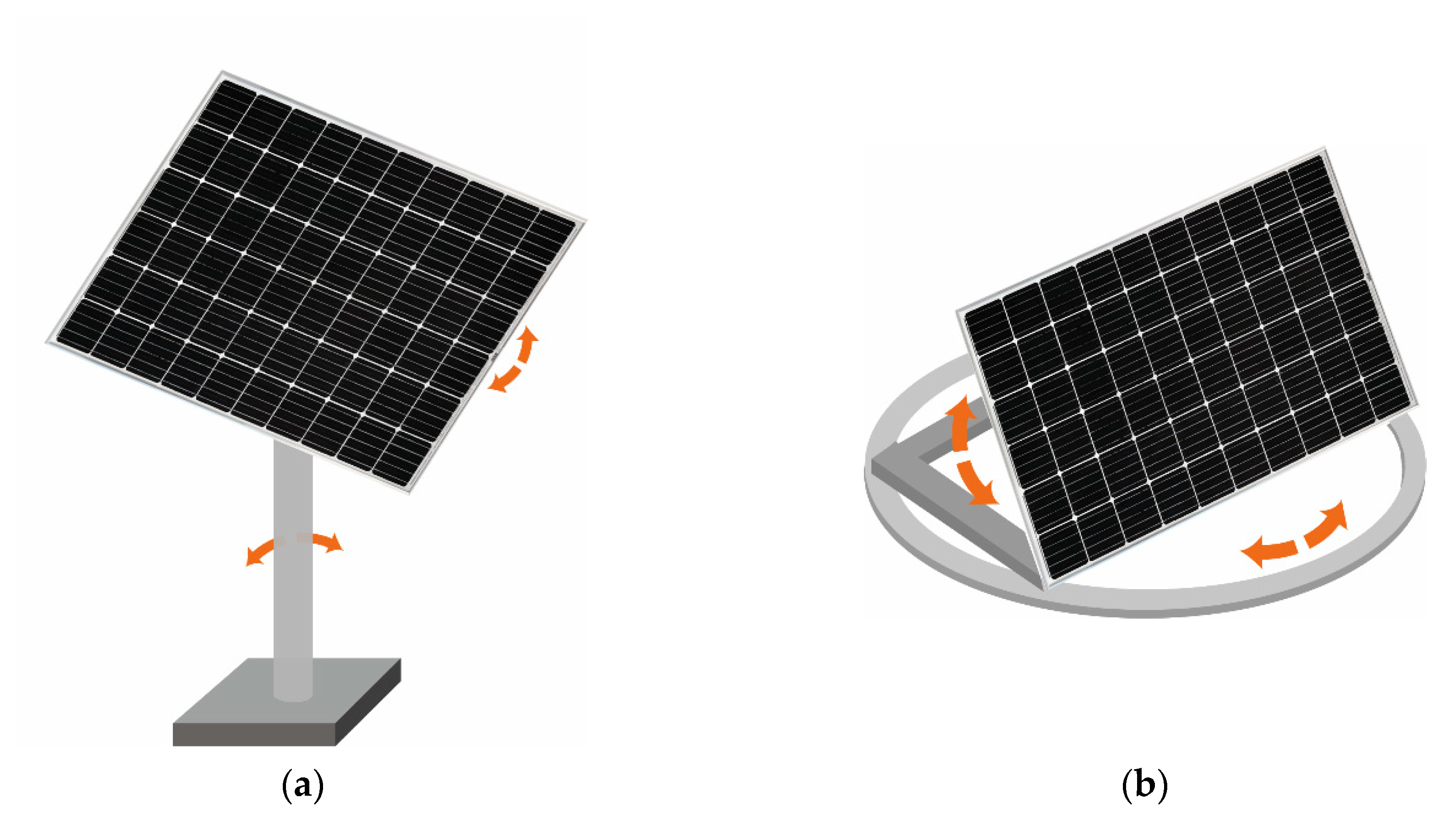

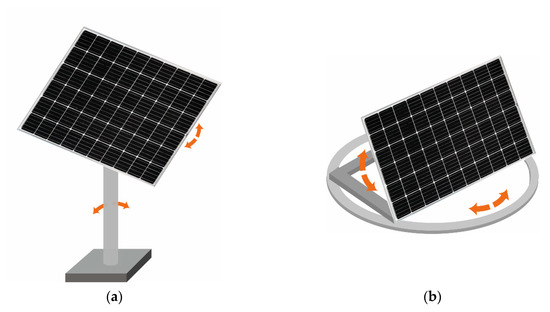

Dual-axis photovoltaic tracking systems are divided into two different types, which are classified by the azimuth of their primary axes with respect to the ground. Two common types are azimuth-altitude tracking system and tip-tilt tracking system.

- Tip-tilt dual-axis tracking system (TTDAT) [53]

A tip-tilt dual-axis tracking system (TTDAT) has its primary axis horizontal to the ground, while the secondary axis is normal to the primary axis.

- Azimuth-altitude dual-axis tracking system [53]

An azimuth-altitude dual-axis tracking system (AADAT) has its primary axis vertical to the ground, while the secondary axis is normal to the primary axis. Figure 7 presents different types of dual-axis photovoltaic tracking systems.

Figure 7.

Dual-axis photovoltaic tracking systems: (a) TTDAT and (b) AADAT.

Table 1 shows the description and key findings of recent and the most interesting studies of single and dual-axis tracking photovoltaic systems. Some of the studies have already been presented in the introduction or will be presented under the following chapters.

Table 1.

Summary of some important studies focusing on single- and dual-axis PV tracking systems.

5. Classification Based on Control System

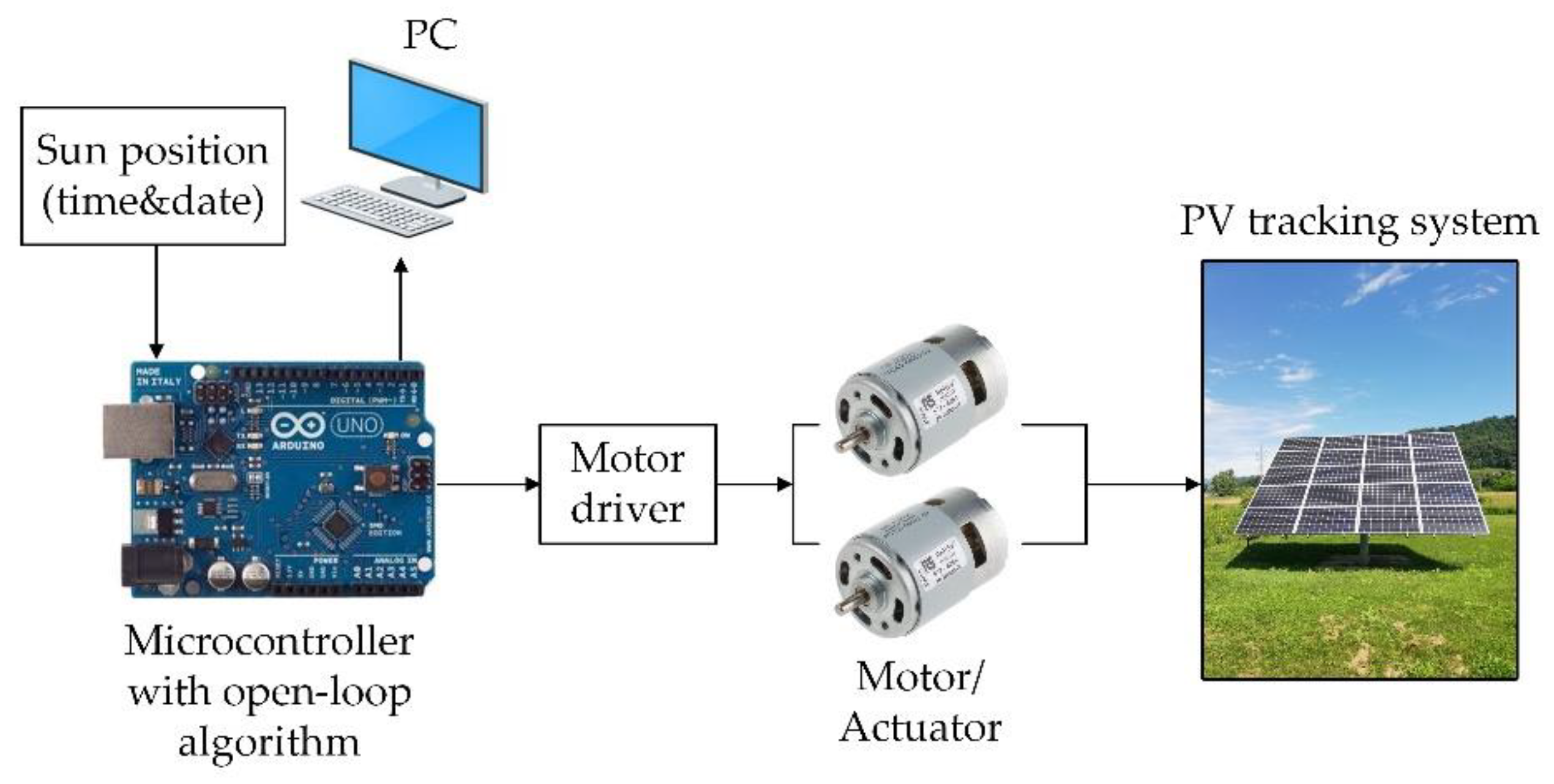

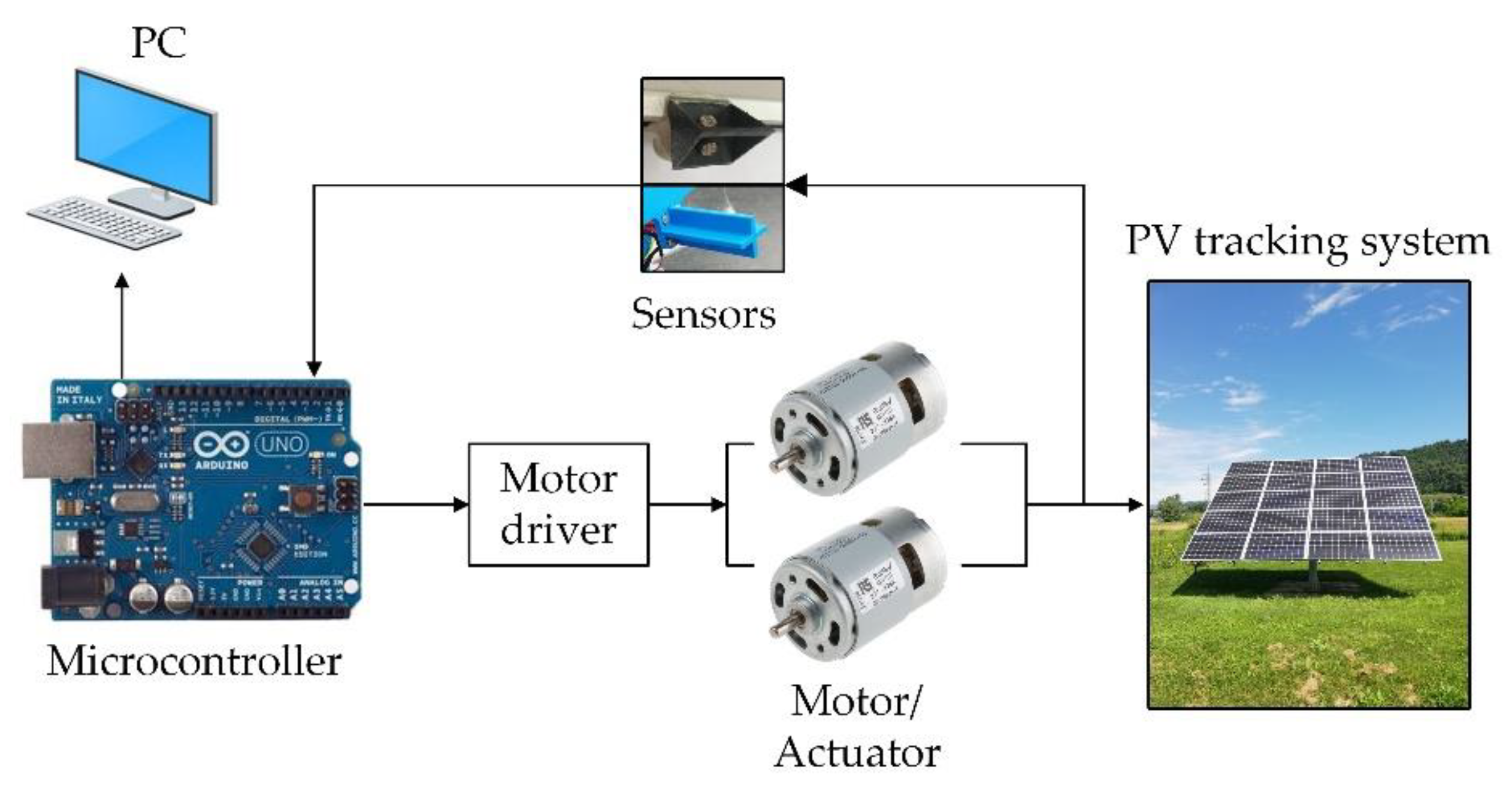

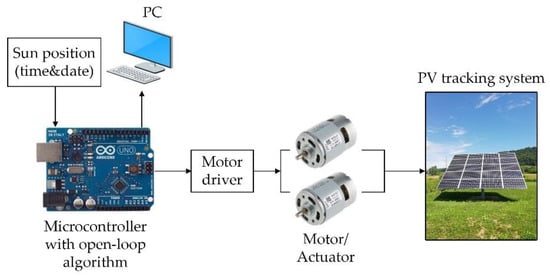

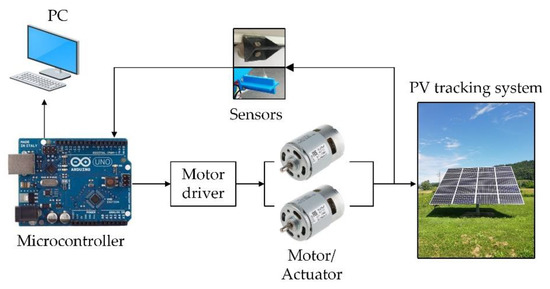

As mentioned in Section 3, active tracking systems can be classified into three categories: closed-loop control system, open-loop control system, and hybrid control system. The open-loop control system [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89] uses a mathematical algorithm for determining the position of the tracking photovoltaic system. The position of the modules can be determined precisely, as the relative position of the sun is precisely determined for any location on earth using the relations between the sun and the earth (description of angles in Section 4). The algorithm is loaded into the microprocessor and is based on date and time control without the use of feedback to evaluate results [30]. Therefore, they cannot correct the errors that occur during the tracking process. The closed-loop control system [90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97] is based on a feedback control system from sensors (light dependent resistors) and moves the axes of the PV tracking system after the sensor detects the position of the sun. The closed-loop control tracking systems are more expensive than open-loop because of the additional sensor devices. In the event of a change in weather, closed-loop systems can consume more energy than is produced by the PV system, so the combination of both systems offers additional benefits and is called a hybrid control tracking system [98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106]. Schematics of closed-loop and open-loop tracking system are presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Schematics of open-loop photovoltaic tracking system.

Figure 9.

Schematics of closed-loop photovoltaic tracking system.

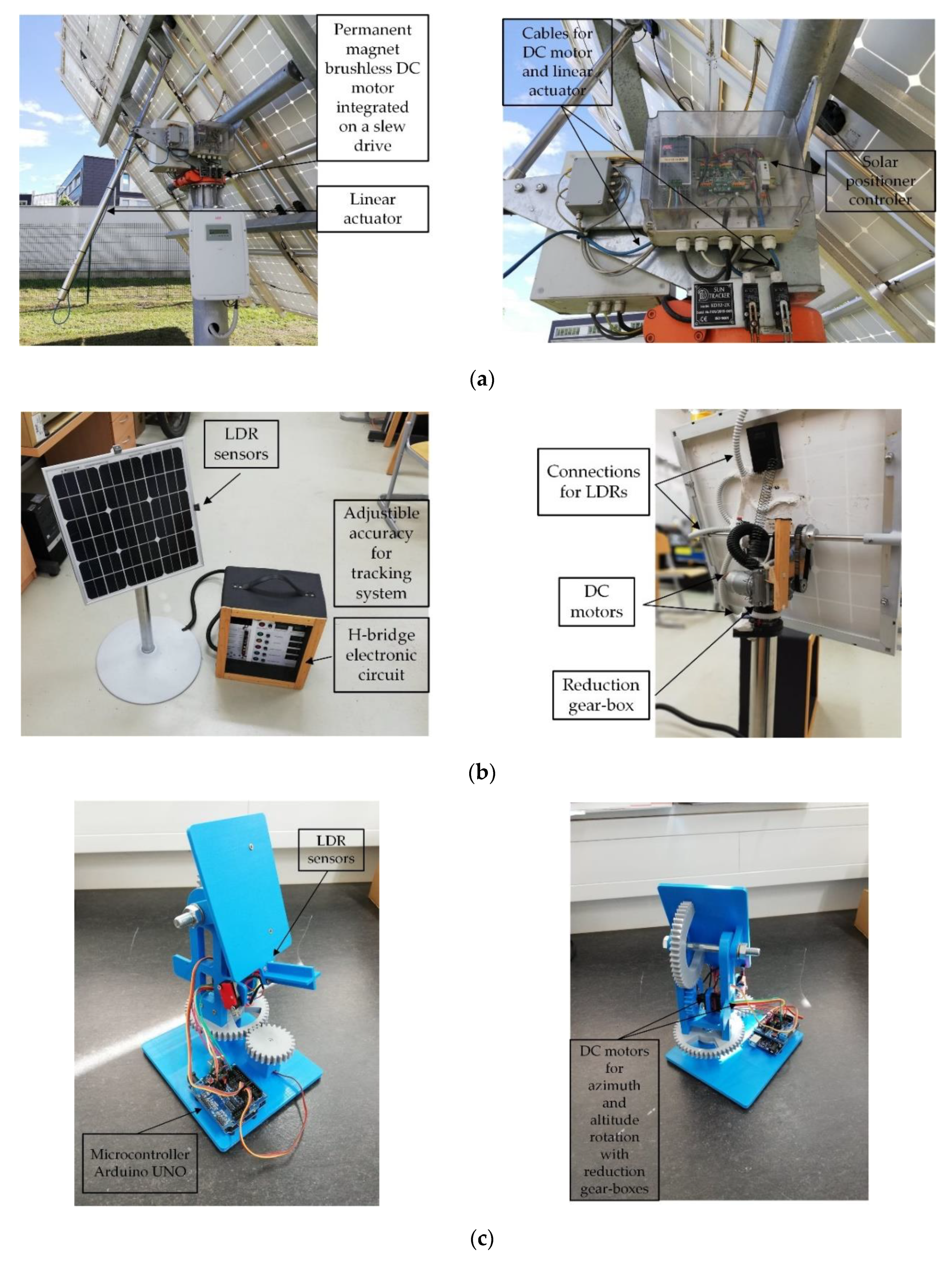

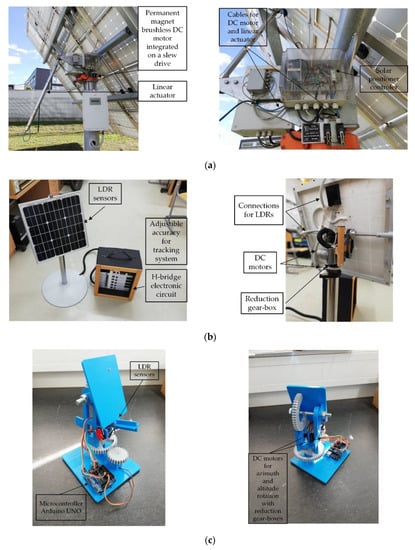

Figure 10 shows some interesting examples of dual-axis closed-loop and open-loop tracking systems that are installed at the Institute of Energy Technology, University of Maribor, Slovenia. The PV tracking systems presented in Figure 10 are further divided into large, medium, and small-scale PV tracking systems. Table 2 shows the description and key findings of recent and most interesting studies of closed-loop, open-loop, and hybrid control photovoltaic tracking systems.

Figure 10.

Different examples of (a) open-loop and (b), (c) closed-loop dual-axis tracking systems.

Table 2.

Summary of some important studies focusing on closed -loop, open-loop, and hybrid control tracking systems.

Large-scale PV tracking systems (see Figure 10a) are those systems (commercial) that are connected to the grid and produce electrical energy. Their powers range from a few kWp to a few MWp of installed power. Large-scale PV tracking systems are most often used in the literature for analyses between different types of systems (comparison of fixed systems with single-axis and two-axis systems). Most often, researchers in the literature use medium-scale PV systems (see Figure 10b) for different research studies (comparison of different powertrains, control strategies, etc.,). In the literature, it is also possible to find small-scale PV tracking (see Figure 10c) systems, which are low-cost and are intended for educational purposes (training toolkits) in higher education institutions.

6. Commercial Photovoltaic Tracking Systems

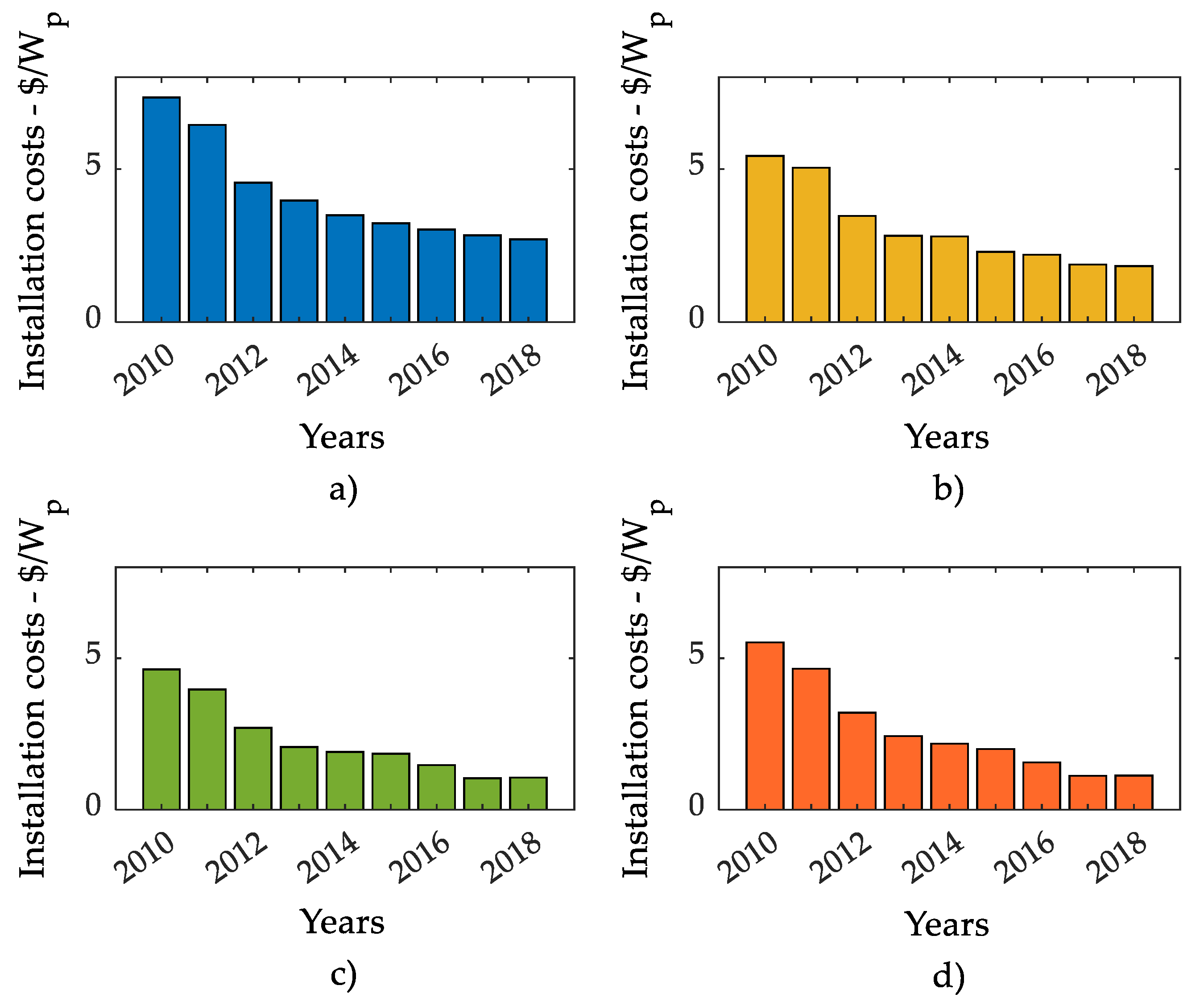

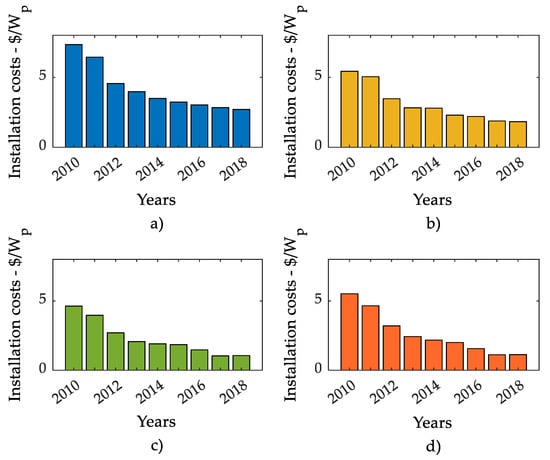

As already presented in Section 5, photovoltaic tracking systems can be divided also on large-scale, medium-scale, and small-scale photovoltaic tracking systems. The emphasis was made on medium-scale and small-scale tracking systems which are mainly presented in research studies. Therefore, a brief presentation of large-scale or commercial type of tracking systems will also be provided, covering everything from different types of components to installation prices worldwide. Commercial and research photovoltaic tracking systems do not differ much from each other in terms of components, but rather in terms of size and robustness. The most commonly used components for a control system are a programmable logic controller (PLC), a variable frequency drive (VFD), a global positioning system (GPS), an inclinometer, a GMT clock and a multi slave system (microcontroller, communication bus, etc.,). Furthermore, the components of the drive system are mostly DC/stepper motors with mounted gearbox or belt/chain drive, linear actuators and hydraulic cylinders, but it also depends on the number of moving axles [107]. According to various reports and studies, the most commonly used types of single-axis and dual-axis tracking systems are TSAT and TTDAT. For utility-scale layouts, it is necessary to ensure the optimal position between the tracking systems, due to shading. At the same time, excessive dispersion of tracking systems can drastically affect the price of land and consequently the entire project, as on average tracking system needs 35–40% more working area compared to a fixed photovoltaic system [108]. In addition, it should be noted that the prices of both commercial fixed and commercial tracking systems are lower each year, due to the reduction of production costs and the abolition of certain subsidies. Figure 11 shows the installation costs for residential (from 3 kW to 10 kW), commercial (from 10 kW to 2 MW), utility-scale fixed (>2 MW), and utility-scale photovoltaic tracking systems (>2 MW).

Figure 11.

Installation costs for (a) residential, (b) commercial, (c) utility-scale fixed and (d) utility-scale tracking photovoltaic system (U.S. market).

Figure 11 shows a drastic decline in the installation costs for photovoltaic systems between 2010 and 2018 [109]. It can also be seen that the installation costs of a utility-scale photovoltaic tracking system are almost equal to the installation costs of a classic fixed photovoltaic system. The installation cost of a dual-axis tracking system shown in Figure 10a was 2.11 €/Wp in 2015, which is very similar to market prices in the U.S. (1.84 €/Wp).

7. Conclusion and Future Trends in Solar Photovoltaic Systems

Photovoltaic tracking systems represent an area in which a great deal of research has been done. However, the field itself is so wide that there is always space for innovations or improvements. One of the primary reasons for the production and development of photovoltaic tracking systems is the low efficiency of photovoltaic modules and, consequently, the lower generation of electrical energy. Systems that improve the yield of conventional PV systems are photovoltaic tracking systems, PV systems with concentrating mirrors (CPV), and photovoltaic/thermal hybrid systems (PV/T). Each of these systems has the potential to increase the yield of electrical energy. However, no innovative system containing the properties of all three systems was found in the literature. Given that the installation of conventional fixed systems is less expensive and much more widespread throughout the world, additional state subsidies should be introduced to enable the wider use and installation of photovoltaic tracking systems. In Slovenia, legislation prescribes that one does not need a building permit for the installation of photovoltaic tracking systems, which is an advantage over the installation of fixed PV systems that are not installed on household facilities. A review of the literature on photovoltaic tracking systems is classified according to the driving system, the degree of freedom and the control system. Based on the reviewed literature, we can highlight the most important findings:

- Single-axis and dual-axis photovoltaic tracking system, with appropriate control systems, the electrical energy can increase from 22–56%, compared to fixed PV system.

- Combinations of microprocessor- and sensor-based control systems represent the most commonly used control method as well as the most efficient.

- Active tracking systems use electrical drives to move the axis, which can consume a huge amount of electrical energy because of improper control systems. Therefore, it is necessary to optimize the power consumption of electrical drives, which can be done by reducing the number of motor movements.

- Sensor-based photovoltaic tracking systems are more expensive because of additional sensor devices, but provide lower tracking error (0.14°), compared to sensorless photovoltaic tracking systems (0.43°).

- Electric motors used in PV tracking applications are exposed to weather conditions and are therefore designed to withstand strong winds, and high temperatures and humidity. The most commonly used electric motor is permanent magnet brushless DC motors as they are easy to maintain.

- Novel innovative tracking systems will include dynamic weather forecasting and cooling of the PV system with wind or water.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Data Platform. Available online: https://www.statista.com (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Tyagi, V.; Rahim, N.A.; Rahim, N.; Jeyraj, A.; Selvaraj, L. Progress in solar PV technology: Research and achievement. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 20, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adawi, M.K.; Al-Nuaim, I.A. The temperature functional dependence of VOC for a solar cell in relation to its efficiency new approach. Desalination 2007, 209, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Singh, S.N.; Lal, M.; Husain, M. Temperature dependence of I-V characteristics and performance parameters of silicon solar cell. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2008, 92, 1611–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siecker, J.; Kusakana, K.; Numbi, B.P. A review of solar photovoltaic systems cooling technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; Sivoththaman, S.; Szlufcik, J.; De Clercq, K.; Duerinckx, F.; Van Kerschaever, E.; Einhaus, R.; Poortmans, J.; Vermeulen, T.; Mertens, R. Overview of solar cell technologies and results on high efficiency multicrystalline silicon substrates. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 1997, 48, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, R.A.; Sarker, M.R.I.; Parvez, R. An Experimental Investigation on Photovoltaic Power output through Single Axis Automatic controlled sun tracker. In Proceedings of the 4th BSME-ASME, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 27–29 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.M.; Yuan, X.Y.; Guo, Y.; Xu, F.; Li, Z.G. Modelling and simulation of a two-axis tracking system. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I J. Syst. Control Eng. 2010, 224, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, K.S.; Saqib, M.A.; Akhter, P.; Ahmed, M.M.; Chattha, J.A.; Yousafzai, S.A. A simple photo-voltaic tracking system. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2005, 87, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, T.T.N.; Mohamed, A.; Khan, R.J.; Amin, N. A Novel Active Sun Tracking Controller for Photovoltaic Panels. J. Appl. Sci. 2009, 9, 4050–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, F.R.; Ortega, M.G.; Gordillo, F.; Lopez-Martinez, M. Application of new control strategy for sun tracking. Energy Convers. Manag. 2007, 48, 2174–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, S.; Badran, O.O. Sun tracking system for productivity enhancement of solar still. Desalination 2008, 220, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacira, M.; Simsek, M.; Babur, Y.; Demirkol, S. Determining optimum tilt angles and orientations of photovoltaic panels in Sanliurfa, Turkey. Renew. Energy 2004, 29, 1265–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visa, I.; Diaconescu, D.V.; Duta, A.; Popa, V. PV tracking data needed in the optimal design of the azimuthal tracker’s control program. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Optimization of Electrical and Electronic Equipment (OPTIM), Brasov, Romania, 22–24 May 2008; pp. 449–454. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandru, C. The design and optimization of a photovoltaic tracking mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Power Engineering, Energy and Electrical Drives Proceedings, Lisbon, Portugal, 18–20 March 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandru, C.; Pozna, C. Simulation of a dual-axis solar tracker for improving the performance of a photovoltaic panel. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 2010, 224, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandru, C.; Pozna, C. The optimization of the tracking mechanism used for a group of PV panels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality (ICREPQ), Valencia, Spain, 15–17 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandru, C.; Comsit, M. The energy balance of the photovoltaic tracking systems using virtual prototyping platform. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on the European Electricity Market (EEM), Lisbon, Portugal, 28–30 May 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Lopez, J.M.; Jimenez Betancourt, R.O.; Ramirez Arredondo, J.M.; Villalvazo Laureano, E.; Rodriguez Haro, F. Incorporating Virtual Reality into the Teaching and Training of Grid-Tie Photovoltaic Power Plants Design. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, A.Z.; Yousef, A.M.; Harag, N.M. Solar tracking systems: Technologies and trackers drive types—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 754–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akash, A.; Shukla, K.; Manohar, M.S.R.; Dondariya, C.; Shukla, K.N.; Porwal, D.; Richhariya, G. Review on sun tracking technology in solar PV system. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Murtaza, A.F.; Sher, H.A. Power tracking techniques for efficient operation of photovoltaic array in solar applications—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpodi, E.K.; Tjiparuro, Z.; Matsebe, O. Review of dual axis solar tracking and development of its functional model. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 35, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, A.Z.; Yousef, A.M.; Soliman, A.; Ismail, I.M. A comprehensive review for solar tracking systems design in Photovoltaic cell, module, panel, array, and systems applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE 7th World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conversion (WCPEC) (A Joint Conference of 45th IEEE PVSC, 28th PVSEC & 34th EU PVSEC), Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 10–15 June 2018; pp. 1188–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rousan, N.; Isa, N.A.M.; Desa, M.K.M. Advances in solar photovoltaic tracking systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2548–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Kumar, S.; Gehlot, A.; Pachauri, R. An imperative role of sun trackers in photovoltaic technology: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3263–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsengiyumva, W.; Chen, S.G.; Hu, L.; Chen, X. Recent advancements and challenges in Solar Tracking Systems (STS): A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumathi, V.; Jayapragash, R.; Bakshi, A.; Akella, P.K. Solar tracking methods to maximize PV system output—A review of the methods adopted in recent decade. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 74, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorat, P.A.; Edalabadkar, A.P.; Chadge, R.B.; Ingle, A. Effect of sun tracking and cooling system on Photovoltaic Panel: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 12630–12634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Khan, M.K.; Pathak, M. Performance enhancement of solar collectors—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Electrotechnical Commision. IEC 61836 (Solar Photovoltaic Energy Systems—Terms and Symbols); International Electrotechnical Commision: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- International Electrotechnical Commision. IEC 60904-3:2019 Photovoltaic Devices—Part 3: Measurement Principles for Terrestrial Photovoltaic (PV) Solar Devices with Reference Spectral Irradiance Data; International Electrotechnical Commision: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- International Electrotechnical Commision. IEC 61277:1995 Terrestrial Photovoltaic (PV) Power Generating Systems—General and Guide; International Electrotechnical Commision: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Diez, F.J.; Navas-Gracia, L.M.; Martínez-Rodríguez, A.; Correa-Guimaraes, A.; Chico-Santamarta, L. Modelling of a flat-plate solar collector using artificial neural networks for different working fluid (water) flow rates. Sol. Energy 2019, 188, 1320–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Lee, H.; Kang, W.; Cho, H. Energy and exergy comparison of a flat-plate solar collector using water, Al2O3 nanofluid, and CuO nanofluid. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 159, 113959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, H.; Arslan, K.; Eltugral, N. Experimental investigation of thermal performance of an evacuated U-Tube solar collector with ZnO/Etylene glycol-pure water nanofluids. Renew. Energy 2018, 122, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Cho, H. Experimental study on performance improvement of U-tube solar collector depending on nanoparticle size and concentration of Al2O3 nanofluid. Energy 2017, 118, 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafieian, A.; Khiadani, M.; Nosrati, A. A review of latest developments, progress, and applications of heat pipe solar collectors. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 95, 273–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, N.; Kumar, R.S.; Karunakaran, G.; Venkatesh, M. Experimental investigation on the thermal performance of heat pipe solar collector (HPSC). Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 26, 3569–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaj, M.S.; Mohiabadi, M.Z. Experimental investigation of heat pipe solar collector using MgO nanofluids. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2019, 191, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafieian, A.; Parastvand, H.; Khiadani, M. Comparative and performative investigation of various data-based and conventional theoretical methods for modelling heat pipe solar collectors. Sol. Energy 2020, 198, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Gao, C.; Xian, H.; Du, X. Thermal Properties of Solar Collector Comprising Oscillating Heat Pipe in a Flat-Plate Structure and Water Heating System in Low-Temperature Conditions. Energies 2018, 11, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shittu, S.; Diallo, T.M.O.; Yu, M.; Zhao, X.; Ji, J. A review of solar photovoltaic-thermoelectric hybrid system for electricity generation. Energy 2018, 158, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudholi, A.; Sopian, K.; Yazdi, M.H.; Ruslan, M.H.; Ibrahim, A.; Kazem, H.A. Performance analysis of photovoltaic thermal (PVT) water collectors. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 78, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.M.; Tamayo, D.F.B.; Estrada, R.H.C. Design and Construction of a Dual Axis Passive Solar Tracker, for Use on Yucatán. In Proceedings of the ASME 2011 5th International Conference on Energy Sustainability, Washington, DC, USA, 8 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, M.J.; Eastwood, D. Design of a novel passive solar tracker. Sol. Energy 2004, 77, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.K.; Wong, C.W. General formula for on-axis sun-tracking system and its application in improving tracking accuracy of solar collector. Sol. Energy 2009, 83, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huld, T.; Šuri, M.; Cebecauer, T.; Dunlop, E. Optimal mounting strategy for single-axis tracking non-concentrating PV in Europe. In Proceedings of the 23rd European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference, Valencia, Spain, 1–5 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hein, M.; Dimroth, F.; Siefer, G.; Bett, A.W. Characterisation of a 300× photovoltaic concentrator system with one-axis tracking. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2003, 75, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Wang, Z.; Liang, W.; Zhang, X.; Zang, C.; Lu, Z.; Wei, X. Tracking formulas and strategies for a receiver oriented dual-axis tracking toroidal heliostat. Sol. Energy 2010, 84, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seme, S.; Sredenšek, K.; Štumberger, B.; Hadžiselimović, M. Analysis of the performance of photovoltaic systems in Slovenia. Sol. Energy 2019, 180, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tang, R.; Zhong, H. Optical Performance of Horizontal Single-Axis Tracked Solar Panels. Energy Procedia 2012, 16, 1744–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Electrotechnical Commision. IEC TC82/1722/NP: Solar Photovoltaic Tracking Systems—Part 1: Design Qualification for Horizontal One-Axis Solar Tracking System; International Electrotechnical Commision: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Tang, R. Optical performance of vertical single-axis tracked solar panels. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefa, I.; Demirtaş, M.; Çolak, I. Application of one-axis sun tracking system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2009, 50, 2709–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.-J.; Sun, F.S. Feasibility study of one axis three positions tracking solar PV with low concentration ratio reflector. Energy Convers. Manag. 2007, 48, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, X. Design and performance analysis of a solar tracking system with a novel single-axis tracking structure to maximize energy collection. Appl. Energy 2020, 264, 114647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthipan, J.; Nagalingeswara Raju, B.; Senthilkumar, S. Design of one axis three position solar tracking system for paraboloidal dish solar collector. Mater. Today Proc. 2016, 3, 2493–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.-J.; Ding, W.L.; Huang, Y.C. Long-Term field test of solar PV power generation using one-axis 3-position sun tracker. Sol. Energy 2011, 85, 1935–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.-J.; Huang, Y.-C.; Chen, G.-Y.; Hsu, P.-C.; Li, K. Improving Solar PV System Efficiency Using One-Axis 3-Position Sun Tracking. Energy Procedia 2013, 33, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, S.A. Design and construction of a one-axis sun-tracking system. Sol. Energy 1996, 57, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Yu, Y. Feasibility and optical performance of one axis three positions sun-tracking polar-axis aligned CPCs for photovoltaic applications. Sol. Energy 2010, 84, 1666–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batayneh, W.; Bataineh, A.; Soliman, I.; Hafees, S.A. Investigation of a single-axis discrete solar tracking system for reduced actuations and maximum energy collection. Autom. Constr. 2019, 98, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huld, T.; Cebecauer, T.; Šuri, M.; Dunlop, E. An analysis of one-axis tracking strategies for PV systems in Europe. Prog. Photovolt. 2010, 18, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamroen, C.; Komkum, P.; Kohsri, S.; Himananto, W.; Panupintu, S.; Unkat, S. A low-cost dual-axis solar tracking system based on digital logic design: Design and implementation. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2020, 37, 100618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, B.-H.; Chiu, C.-C.; Lu, W.-T.; Lien, C.-C.; Liu, T.-K.; Chen, W.-P. Dual-Axis rotary platform with UAV image recognition and tracking. Microelectron. Reliab. 2019, 95, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidek, M.H.M.; Azis, N.; Hasan, W.Z.W.; Ab Kadir, M.Z.A.; Shafie, S.; Radzi, M.A.M. Automated positioning dual-axis solar tracking system with precision elevation and azimuth angle control. Energy 2017, 124, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Away, Y.; Ikhsan, M. Dual-Axis sun tracker sensor based on tetrahedron geometry. Autom. Constr. 2017, 73, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathabadi, H. Comparative study between two novel sensorless and sensor based dual-axis solar trackers. Sol. Energy 2016, 138, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbab, H.; Jazi, B.; Rezagholizadeh, M. A computer tracking system of solar dish with two-axis degree freedoms based on picture processing of bar shadow. Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 1114–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, P.; Georgiev, A.; Boudinov, H. Cheap two axis sun following device. Energy Convers. Manag. 2005, 46, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakos, G.C. Design and construction of a two-axis Sun tracking system for parabolic trough collector (PTC) efficiency improvement. Renew. Energy 2006, 31, 2411–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahpour, M.; Golzarian, M.R.; Rohani, A.; Zarchi, H.A. Development of a machine vision dual-axis solar tracking system. Sol. Energy 2018, 169, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathabadi, H. Novel high accurate sensorless dual-axis solar tracking system controlled by maximum power point tracking unit of photovoltaic systems. Appl. Energy 2016, 173, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batayneh, W.; Owais, A.; Nairoukh, M. An intelligent fuzzy based tracking controller for a dual-axis solar PV system. Autom. Constr. 2013, 29, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Gao, S.; Yang, G.; Du, J. A multipurpose dual-axis solar tracker with two tracking strategies. Renew. Energy 2014, 72, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungur, C. Multi-Axes sun-tracking system with PLC control for photovoltaic panels in Turkey. Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, S.; Nijmeh, S. Two axes sun tracking system with PLC control. Energy Convers. Manag. 2004, 45, 1931–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, M.; El-Chaar, L. Two axes sun tracking system: Comparison with a fixed system. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality (ICREPQ), Granada, Spain, 23 March 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, F.; Gaspar, P.D.; Goncalves, L.C. Two axis solar tracker based on solar maps, controlled by a low-poer microcontroller. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality (ICREPQ), Granada, Spain, 23 March 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, M.R.I.; Pervez, M.R.; Beg, R.A. Design, Fabrication and Experimental study of a Novel Two-Axis Sun Tracker. Int. J. Mech. Mechatron. Eng. 2010, 10, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, N.; Bai, Y.; Fu, R.; Liu, H. Open-Loop solar tracking strategy for high concentrating photovoltaic systems using variable tracking frequency. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 117, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-K.; Cheng, T.-C.; Cheng, C.-H.; Wang, C.-C.; Lee, C.-C. Open-Loop altitude-azimuth concentrated solar tracking system for solar-thermal applications. Sol. Energy 2017, 147, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.; Filho, D.O.; de Oliveira, M.J.M.; Zolnier, S.; Ribeiro, A. Development of a closed and open loop solar tracker technology. Acta Sci. Technol. 2017, 39, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, D.C.; Nguyen, T.M.; Dunnigan, M.W.; Mueller, M.A. Comparison between open- and closed-loop trackers of a solar photovoltaic system. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Clean Energy and Technology (CEAT), Langkawi, Malaysia, 18–20 November 2013; pp. 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.E.; Chen, C.H.; Huang, Y.C.; Chen, H.Y. An open-loop solar tracking for mobile photovoltaic systems. J. Aeronaut. Astronaut. Aviat. 2015, 47, 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, K.K.; Wong, C.W. Open-Loop azimuth-elevation sun-tracking system using on-axis general sun-tracking formula for achieving tracking accuracy of below 1 mrad. In Proceedings of the IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 20–25 June 2010; pp. 3019–3024. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.A.; Mahmood, R.; Haque, A. Enhanced energy extraction in an open loop single-axis solar tracking PV system with optimized tracker rotation about tilted axis. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 045301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandru, C. A Novel Open-Loop Tracking Strategy for Photovoltaic Systems. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 205396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, M.E.H.; Khandakar, A.; Hossain, B.M.; Abouhasera, R. A Low-Cost Closed-Loop Solar Tracking System Based on the Sun Position Algorithm. J. Sens. 2019, 2019, 3681031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, R.; Díaz, A. Cascade closed-loop control of solar trackers applied to HCPV systems. Renew. Energy 2016, 97, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-M.; Lu, C.-L. Design and Implementation of a Sun Tracker with a Dual-Axis Single Motor for an Optical Sensor-Based Photovoltaic System. Sensors 2013, 13, 3157–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeroual, A.; Raoufi, M.; Ankrim, M.; Wilkinson, A.J. Design and construction of a closed loop sun-tracker with microprocessor management. Int. J. Sol. Energy 1998, 19, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.A.; Beckman, W.A. A general design method for closed-loop solar energy systems. Sol. Energy 1979, 22, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yi, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. The design of closed-loop control system of solar automatical tracking. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Mechatronic Sciences, Electric Engineering and Computer, Shenyang, China, 29–22 December 2013; pp. 3745–3748. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.; Bobruk, J.; Fromer, N.; McDermott, D. Integrated Closed Loop Tracking System for Rooftop Concentrator Modules. AIP Conf. Proc. 2010, 141, 1277. [Google Scholar]

- López, O.; Penella, M.T.; Gasulla, M. A Closed-Loop Maximum Power Point Tracker for Subwatt Photovoltaic Panels. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 59, 1588–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Men, J.; Shao, L.; Dong, Z.; Liu, W. Research Progress of Solar Auto-Tracking System—Solar Hybrid Tracking Mode. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 706, 985–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, M.; Tarequl, K. Design and Implementation of Hybrid Automatic Solar-Tracking System. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2012, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safan, Y.M.; Shaaban, S.; El-Sebah, M.I.A. Hybrid control of a solar tracking system using SUI-PID controller. In Proceedings of the 2017 Sensors Networks Smart and Emerging Technologies (SENSET), Beirut, Lebanon, 12–14 September 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Safan, Y.M.; Shaaban, S.; Abu El-Sebah, M.I. Performance evaluation of a multi-degree of freedom hybrid controlled dual axis solar tracking system. Sol. Energy 2018, 170, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, V.N.; Gonzatti, F.; Franchi, D.; Miotto, M.; Camargo, M.N.; Farret, F.A. Hybrid motor driver for solar tracking systems. In Proceedings of the 12th IEEE International Conference on Industry Applications (INDUSCON), Curitiba, Brazil, 20–23 November 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, T.; Jeong, K.; Ban, C.; Oh, J.; Koo, C.; Kim, J.; Lee, M. A Preliminary Study on the 2-axis Hybrid Solar Tracking Method for the Smart Photovoltaic Blind. Energy Procedia 2016, 88, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yin, Z.; Jin, P. Error analysis and auto correction of hybrid solar tracking system using photo sensors and orientation algorithm. Energy 2019, 182, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhu, W.; Hu, Y.; Tu, X.; Wu, Y. Design of novel hybrid control solar tracking system. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 69, 12198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.G.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, S.J. Development of a hybrid solar tracking device using a GPS and a photo-sensor capable of operating at low solar radiation intensity. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2015, 67, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shingleton, J. One-Axis Trackers—Improved Reliability, Durability, Performance, and Cost Reduction. In Final Subcontract Technical Status Report, NREL—Subcontract Report; NREL/SR-520-42769; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Denver, CO, USA, 2008; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, A.; James, T.; Woodhouse, M. NREL—Technical Report; NREL/TP-6A20-53347; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Denver, CO, USA, 2012; pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, R.; Feldman, D.; Margolis, R.U.S. Solar Photovoltaic System Cost Benchmark: Q1 2018; NREL—Technical Report; NREL/TP-6A20-72399; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Denver, CO, USA, 2018; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).