Abstract

Australia is one of the leading countries in energy transition, and its largest power system is intended to securely operate with up to 75% of variable renewable generation by 2025. High-inertia synchronous condensers, battery energy storage systems, and grid-forming converters are some of the technologies supporting this transformation while facilitating the secure operation of the grid. Synchronous condensers have enabled 2500 MW of solar and wind generation in the state of South Australia, reaching minimum operational demands of ≈100 MW. Grid-scale battery energy storage systems have demonstrated not only market benefits by cutting costs to consumers but also essential grid services during contingencies. Fast frequency response, synthetic inertia, and high fault currents are some of the grid-supporting capabilities provided by new developments that strengthen the grid while facilitating the integration of new renewable energy hubs. This manuscript provides a comprehensive overview, based on the Australian experience, of how power systems are overcoming expected challenges while continuing to integrate secure, low cost, and clean energy.

1. Introduction

Investment in large-scale renewable generation has accounted more than 60% of new global power generation in the last couple of years [1]. Multiple policy objectives, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions and cost reduction trends, are expected to drive large-scale renewable generation investments to continue to grow faster than other energy generation technologies [2]. However, renewable energy zones (REZs), large-scale geographic areas with high-quality renewable energy resources, are generally situated in remote areas. These locations usually lack nearby synchronous generation and strong transmission connections, which, when combined, result in areas with low fault current and low system strength levels. As a result, the integration of REZ generation projects is limited by existing/planned grid infrastructure, in addition, to new operational challenges.

Since many of REZ projects connect via power electronics converters, their continuous connection further weakens the area. This results in a series of additional challenges if no appropriate measures are taken. Traditional stability (rotor angle, frequency, and voltage), resonance and converter-driven stability, power system protection and coordination, and black-start are some of the technical challenges faced by modern power systems [3,4].

Reinforcing and upgrading the grid is an alternative to overcome with these issues while strengthening the area. However, planning, approving, and building a transmission project to support the integration of new REZs may take several more years when compared with the development of a solar or wind power plant [5]. As a result, and without considering joint network planning, other alternatives are needed to host and support these projects and the network to which they connect. Some grid upgrades include flexible ac transmission systems (FACTS), synchronous condensers (SynCons) [6], battery energy storage systems (BESSs) [7], or a combination of them [8].

The Australian National Electricity Market (NEM) is one of the world’s leading power systems for both large-scale and distributed IBR integration [9,10]. As of November 2021, the NEM presents more than 15 GW of installed capacity between large-scale solar PV and wind, representing near 25% of the total generation capacity [11]. Furthermore, the NEM has more than 10 GW of distributed solar (as at May 2020) [12]. The amount of instantaneous generation from these variable energy resources that can operate on the NEM at any time depends on system conditions (e.g., network congestion, system curtailment, and self-curtails) [13]. In particular, system curtailment limits renewables to preserve the security of NEM by managing frequency and maintaining system strength. Some of the actions that can result in managing power system requirements include the utilization of a range of flexible devices such as high-inertia SynCons and BESSs. Targeted actions together with suitable investments in infrastructure can allow the NEM to operate securely with up to 75% of variable renewable generation by 2025 and near 90% by 2035 [14].

Motivated by the above discussion, this work aims to summarize existing and most common challenges and mitigation measures in modern power systems with a high share of renewable energy. A comprehensive overview, based on the Australian experience, is provided to illustrate how power systems can overcome expected challenges while continuing to integrate secure, low-cost, and clean energy.

The rest of the manuscript is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a summary of challenges in actual power systems and their mitigation measures. Issues observed in Australia are also included in the Section. Trending technologies and how Australia is facilitating the integration of IBRs are presented in Section 3, while their impact in the system is discussed in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

3. Trending Technologies in Australia

The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) is responsible for the day-to-day operation of the Australian NEM. Furthermore, AEMO delivers an integrated planning of the grid that helps to support efficient investments and the development of new renewable energy hubs. Even though projects such as EnergyConnect, a new interconnector between New South Wales and South Australia, unlocks additional renewable generation resources and enhances the security of supply [48], synchronous condensers and battery energy storage systems are offering time-efficient and cost-effective solutions. This Section explores these technologies while listing some of the main projects including them.

3.1. Synchronous Condensers

In its basic definition, a synchronous condenser (SynCon) is a large rotating motor that does not have a driven load connected. The field of a SynCon is controlled by voltage regulators that allows providing reactive power support to the grid. Furthermore, the kinetic energy stored in the inertia system allows enhancing the transient stability of neighboring synchronous generators and can stabilize power systems [49].

As power system evolved, SynCons were phased out due to the increase in power electronics devices controlling the grid [50]. Static VAr compensators (SVCs) and static synchronous compensators (STATCOMs) were the preferable options as they provide fast-acting reactive power compensation. However, the large integration of IBR has weakened power systems, requiring new options that can provide both voltage and inertia support. As a result, SynCons have regained interest and are considered as an option to support the operation of modern power systems.

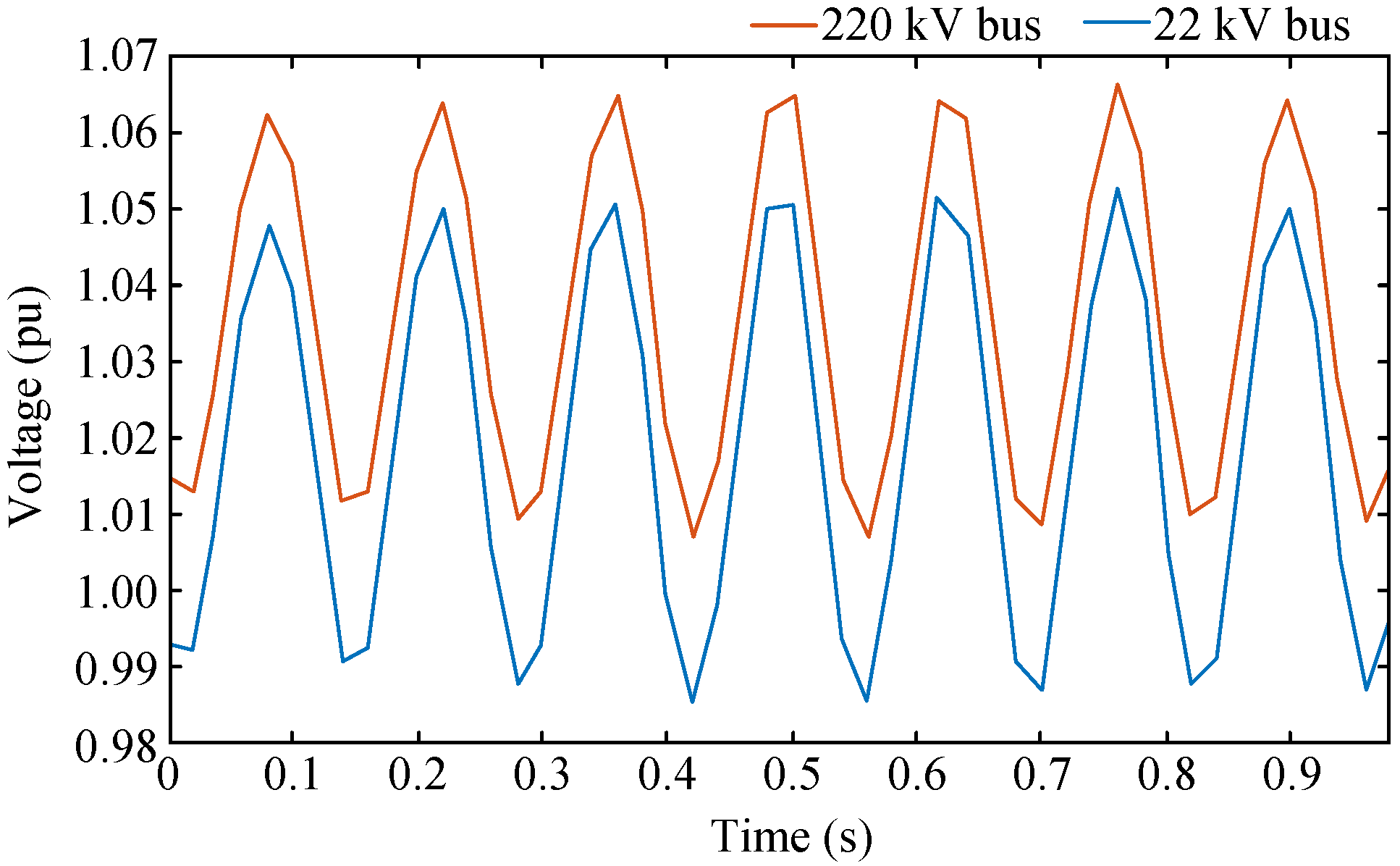

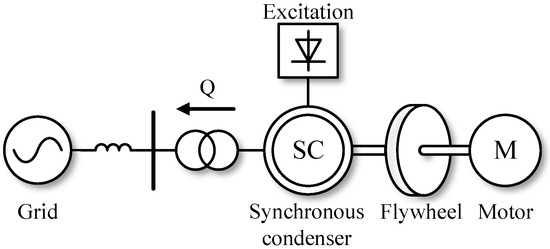

Figure 2 illustrates the main components of a high-inertia SynCon unit. During its energization, a motor is used to bring the SynCon up to the power system synchronous speed. An excitation system is used to start regulating voltage and power factor of the SynCon. The connection to the grid is performed by closing the breaker to the network. After synchronization, the motor is deenergized and runs idle, the flywheel attached to the SynCon unit provides additional inertia to the grid.

Figure 2.

Diagram of a high-inertia synchronous condenser.

In Australia, SynCons are installed to remediate the network impact of new IBR connections and the retirement of traditional power plants (mainly coal) [14]. SynCons with flywheels are seen as options that can further enable the energy transition while providing high and instantaneous inertia support, short-circuit currents, and reactive power compensation. For instance, two synchronous condensers have been installed as an integral part of the Darlington Point Solar Farm in the state of New South Wales [51]. Similarly, Musselroe and Kiamal SynCon units locally improve system strength while remediating the network impact of an IBR connection in Tasmania and Victoria, respectively. The installation of these small/medium units is directly linked to new connections; thus, their planning and execution is project-based.

Larger SynCon units, connected to higher voltages in the transmission system, are installed or planned to overcome system strength shortfalls in larger regional areas. SynCon units at Davenport and Robertstown in South Australia were installed to deliver adequate system strength and system inertia. Armidale, Surat Basin, and Thomastown, among others, SynCon projects are intended to meet system strength requirements at regional levels of the Australian NEM. A list of major SynCons under operation in Australia is shown in Table 2 [52,53]. Table 3 provides a list of indicative synchronous condenser projects that can strengthen the grid while meeting fault level requirements [48,52,54,55].

Table 2.

Operational synchronous condensers in Australia [52,53].

Table 3.

Indicative synchronous condensers projects in Australia [48,52,54,55].

3.2. Battery Energy Storage Systems

Synchronous condensers are not the only solution capable to keep power systems operating securely while transitioning to a more clean energy generation pool. Technologies such as grid-scale battery energy storage systems (BESSs) are seen as more modular and flexible solutions. BESSs can not only provide ancillary and essential grid services (e.g., frequency and voltage management and system restoration) but also cope with the inherent variability of renewable energy systems, contributing to energy balancing. A summary of essential services that a BESS can provide in a power system is shown in Table 4. Even though traditional, grid-following BESSs are suitable for providing several of the functionalities in Table 4, grid-forming BESSs unlock new services.

Table 4.

Grid services of battery energy storage systems.

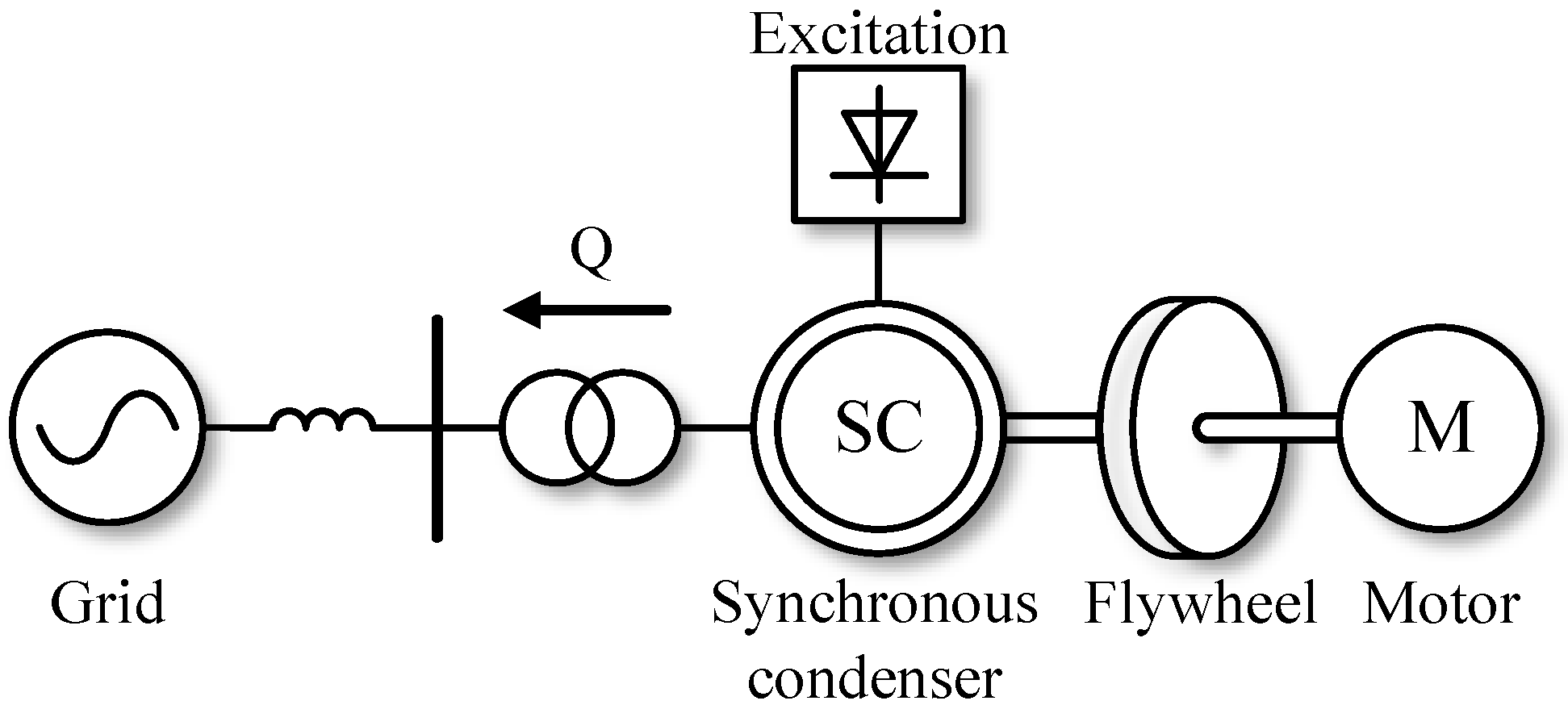

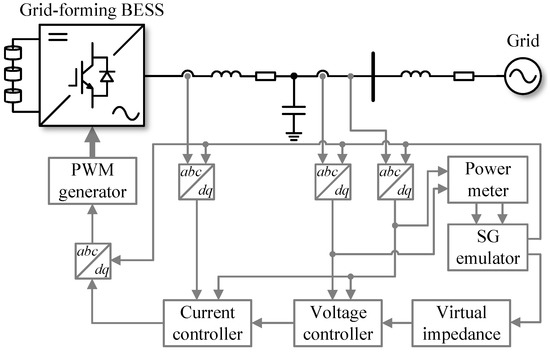

The basic configuration of a grid-forming BESS is shown in Figure 3. A grid-forming BESS operates as a virtual synchronous machine that mimics the external characteristics of a conventional synchronous generator (SG). As mentioned in Section 2.3.4, one of the salient features of a grid-forming converter, compared to a conventional grid-following converter, is the absence of the PLL used for grid synchronization. PLLs can still be adopted to measure the simultaneous frequency for implementing high-level controls; however, it is no longer a critical element for the operation of the converter. Consequently, a grid-forming BESS is designed to self-synchronize to the grid or directly operate in island mode based on internal phase references. The removal of PLLs makes grid-forming BESSs robust to voltage/frequency disturbances coming from the main grid.

Figure 3.

Control structure of a grid-forming battery energy storage system.

The SG emulator is the critical part in the control frame of GFM BESSs. The emulator replicates the characteristics of SGs by incorporating swing equations and active voltage regulations (AVRs) in the digital control. Swing equations are used to realize fast reference track and provide virtual inertia, while mitigating possible overshoots in the cases of grid events. The digital implementation allows flexible selection of virtual synchronous generator parameters in order to maximize these capabilities of GFM BESSs within power rating limits [56]. Similarly, parameters in the AVR control, which correspond to the excitation of the SG, can be selected with certain freedom to improve the dynamic response of reactive power and facilitate voltage regulation.

A virtual impedance block can also be incorporated in the control loop of GFM BESSs to become accustomed to weak grids. In the context of large-scale systems, the virtual impedance block enhances reactive power sharing capabilities of multiple BESSs connected in parallel [57]. Moreover, the virtual resistance component helps mitigate a wide frequency range of resonance related to impedance mismatching, inappropriately tuned controllers, or improper control setups [58]. In comparison to utilizing passive damping circuits, virtual impedance does not introduce unexpected power losses.

All these functionalities of GFM BESSs, however, are subject to the available energy capacity of battery packs and the overcurrent capability of the converter interface. The designers are supposed to trade off the need of investment curtailment against the capability of providing grid services. Currently, grid-following BESSs are still common solutions for power systems, but the progress towards the technical maturity allows grid-forming BESSs to become more common in future power systems.

Grid-scale batteries have been already commissioned in Australia, and there are more than 80 projects planned (with a total capacity of 18,660 MW). Table 5 and Table 6 list operational and announced BESSs in the Australian NEM, respectively [11]. Other power systems in Australia, such as the South West Interconnected System, have also installed grid-scale BESSs. A 30 MW, 11.4 MWh battery has been commissioned at Newman power station in 2018. Furthermore, the system is expected to integrate two 100 MW, 200 MWh in Kwinana and Wagerup in Western Australia [59].

Table 5.

Operational battery energy storage systems in Australia [11].

Table 6.

Announced battery energy storage systems in Australia [11].

4. Impact of Trending Technologies in Australia

This Section provides a set of cases in which trending technologies, as discussed in Section 3, have positively impacted the operation of the Australian National Electricity Market (NEM).

4.1. Synchronous Condenser—The South Australian Experience

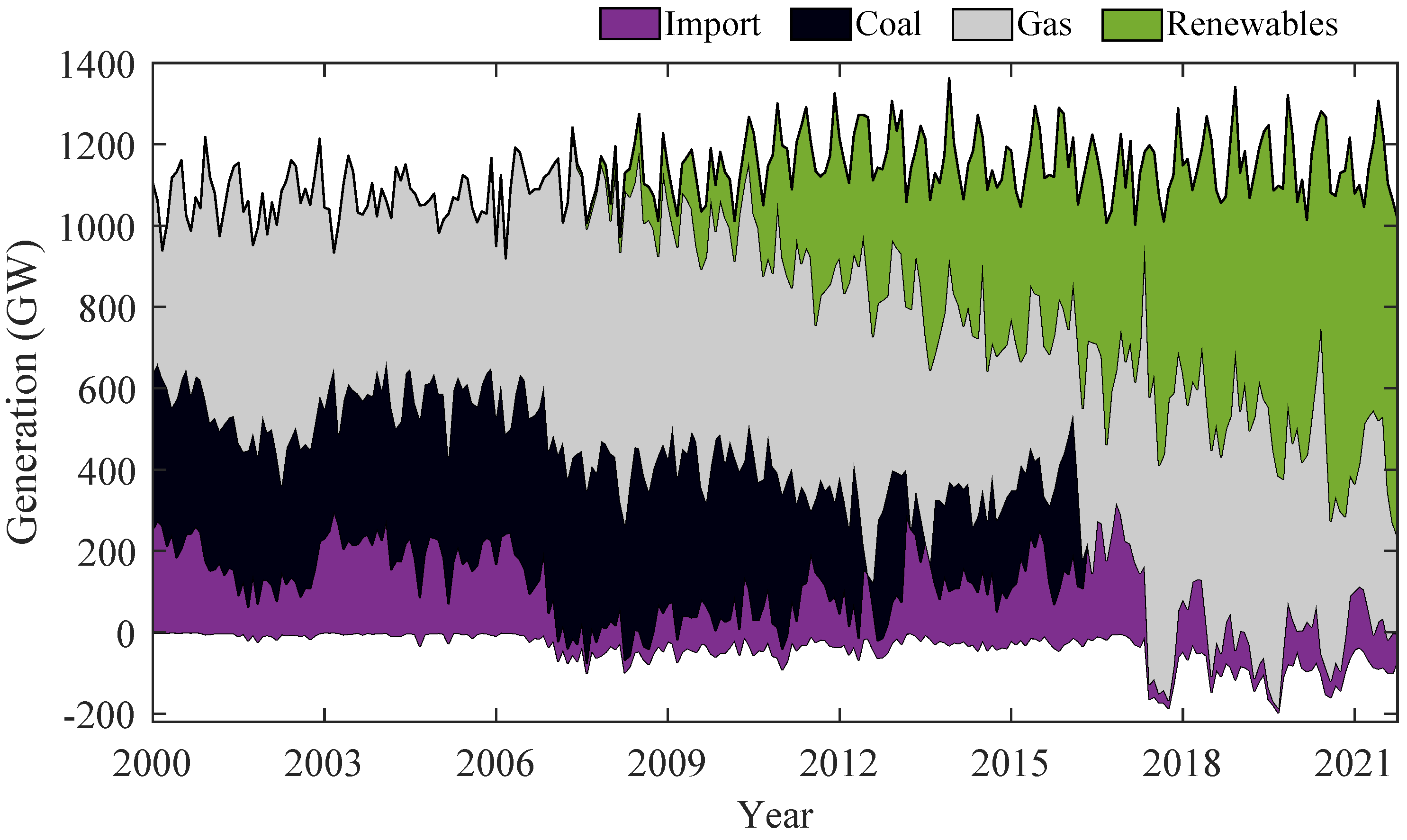

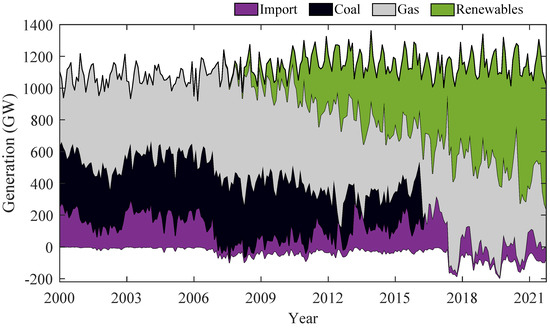

The state of South Australia is well known by its rapid transition to renewable generation. The increase in renewable energy generation has totally displaced coal-based generation and reduced imports from neighboring states and gas-based generating units. Figure 4 shows the energy mix in South Australia in the last 21 years [60].

Figure 4.

Monthly generation mix in South Australia since the year 2000. Renewable energy has displaced coal and gas power plants (plot drawn with data from [60]).

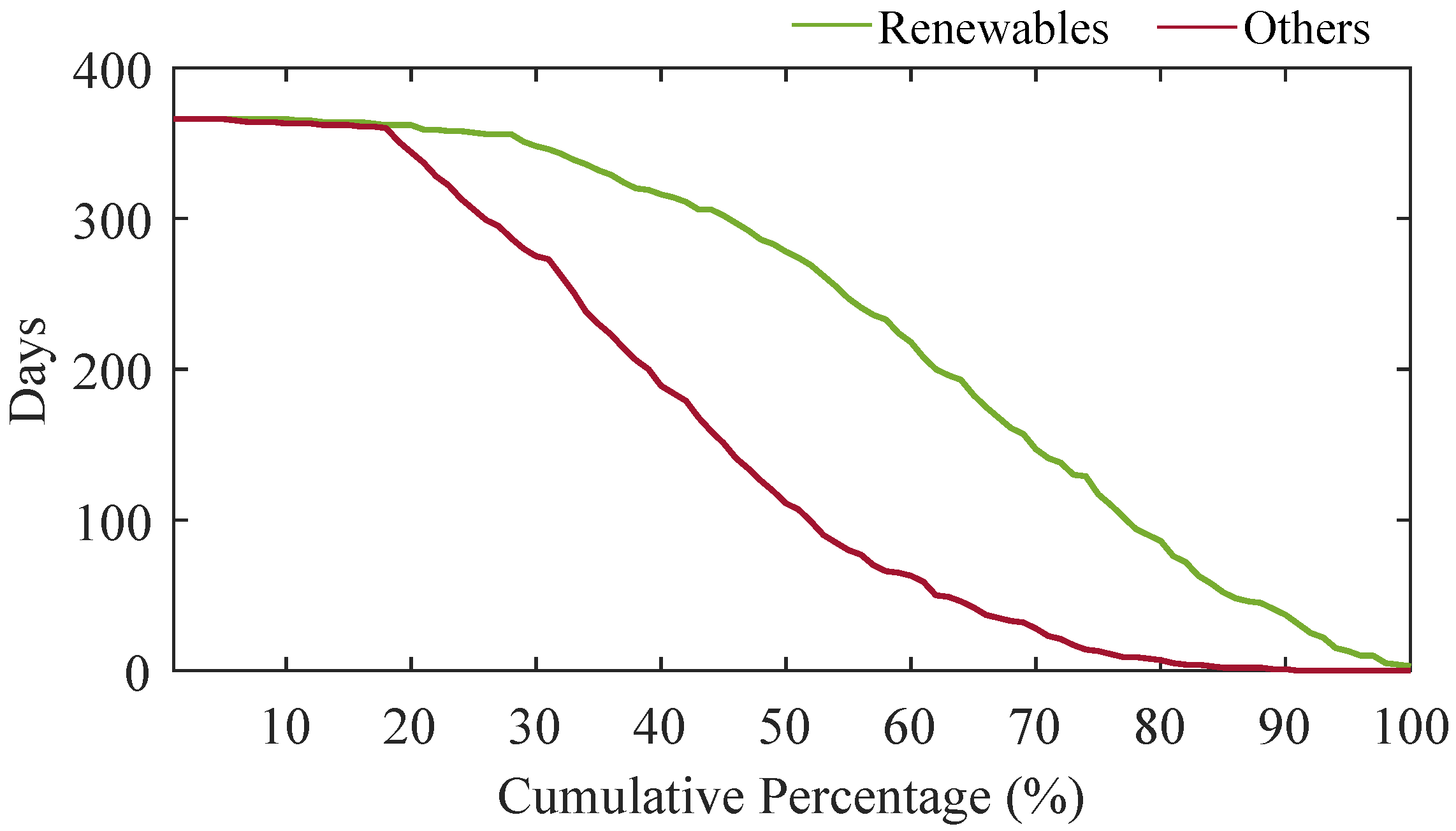

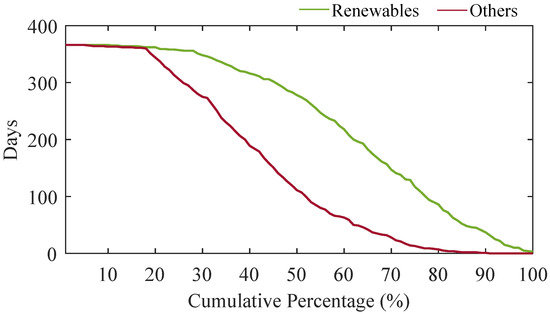

The gigawatt-scale South Australian grid is also demonstrating how IBR renewable energy can supply more than 60% of demand while keeping a secure and reliable electricity service. In the last calendar year (December 2020 to December 2021), 76.2% of the days had an IBR generation (wind, solar PV, BESS, and rooftop PV) over half the total generation of the state. Furthermore, 52.7% and 10.1% of annual IBR generations were more than 60% and 90% of the total generation, respectively. Figure 5 shows this cumulative renewable energy generation distribution for the calendar year [60].

Figure 5.

Cumulative renewable energy generation participation in South Australia during December 2020 to December 2021 (plot drawn with data from [60]).

After the blackout event of South Australia on 28 September 2016, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) defined that at least three synchronous generating units, each with an installed capacity of 100 MW or more, are required to be connected at all times [43]. Additional operational constraints were also placed to meet minimum system strength requirements. These conditions, together with fault level shortfalls, result in costly dispatches of high-priced gas generation units, the curtailment of renewable energy, and the need for new and most efficient solutions [61,62]. As a result, ElectraNet, the Transmission Network Service Provider (TNSP) and System Strength Service Provider (SSSP) in South Australia, performed an economic analysis that determined that installing synchronous condensers on the transmission network was the most cost-effective solution in the short to medium term.

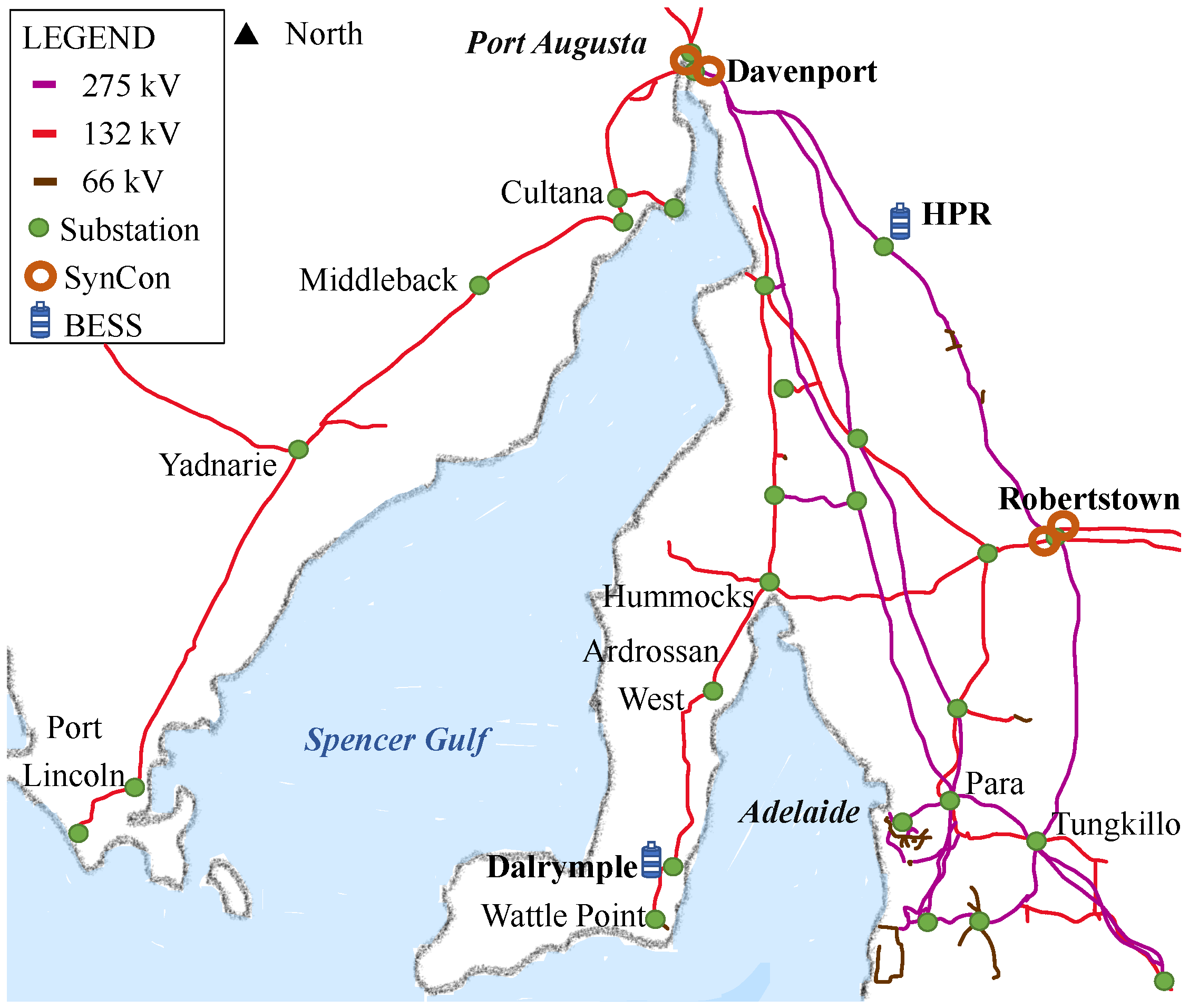

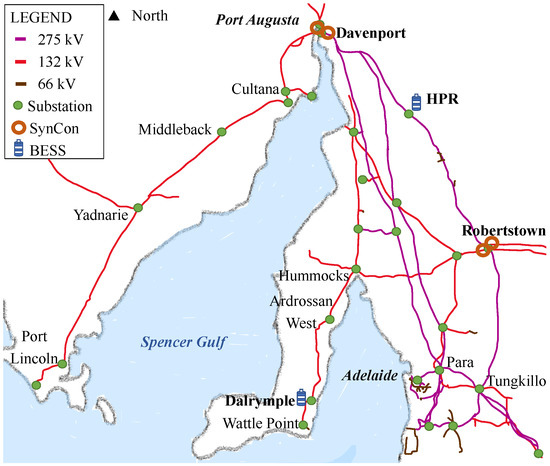

A complete technical assessment was carried out by ElectraNet and endorsed by AEMO [63]. The solution, consisting of the installation of four large SynCons on the transmission network, had a total capital cost of about A$190 million. The installation of all four synchronous condensers has been completed by September 2021. Each SynCon unit has a fault capability of 575 MVA at 275 kV, which helps to meet the system’s strength gap (fault level shortfall). Furthermore, to meet inertia requirements, synchronous condensers are equipped with flywheels to provide 1100 MWs, a total of 4400 MWs of inertia. Figure 6 shows the location of the synchronous condensers.

Figure 6.

Simplified diagram of the South Australian grid.

The constant operation of at least three synchronous generating units has been changed to take into account the benefits provided by SynCons. While the operation of all four SynCons, with high inertia flywheels, enables dispatching up to ∼2500 MW of IBRs, at least two large synchronous thermal units need to be connected under normal system conditions [64]. Traditional synchronous generators are still necessary to continuously provide active power support and maintain sufficient ramping control and reactive power support. Table 7 shows some of the combinations for a secure state of the South Australian network for different levels of IBR generation under normal system conditions. These combinations allow withstanding a credible fault and loss of a synchronous generating unit in South Australia at different IBR generation levels.

Table 7.

South Australia minimum generator combinations under system normal operation [64].

When South Australia is on a credible risk of island or operating as an island, the same generator combinations for four SynCons is valid (refer to Table 7). However, combinations for two or non SynCons change as sufficient inertia, frequency response, and generation power are required to ensure power system security. Table 8 summarizes some of the combinations that are needed under these circumstances.

Table 8.

South Australia minimum generator combinations under islanding operation [64].

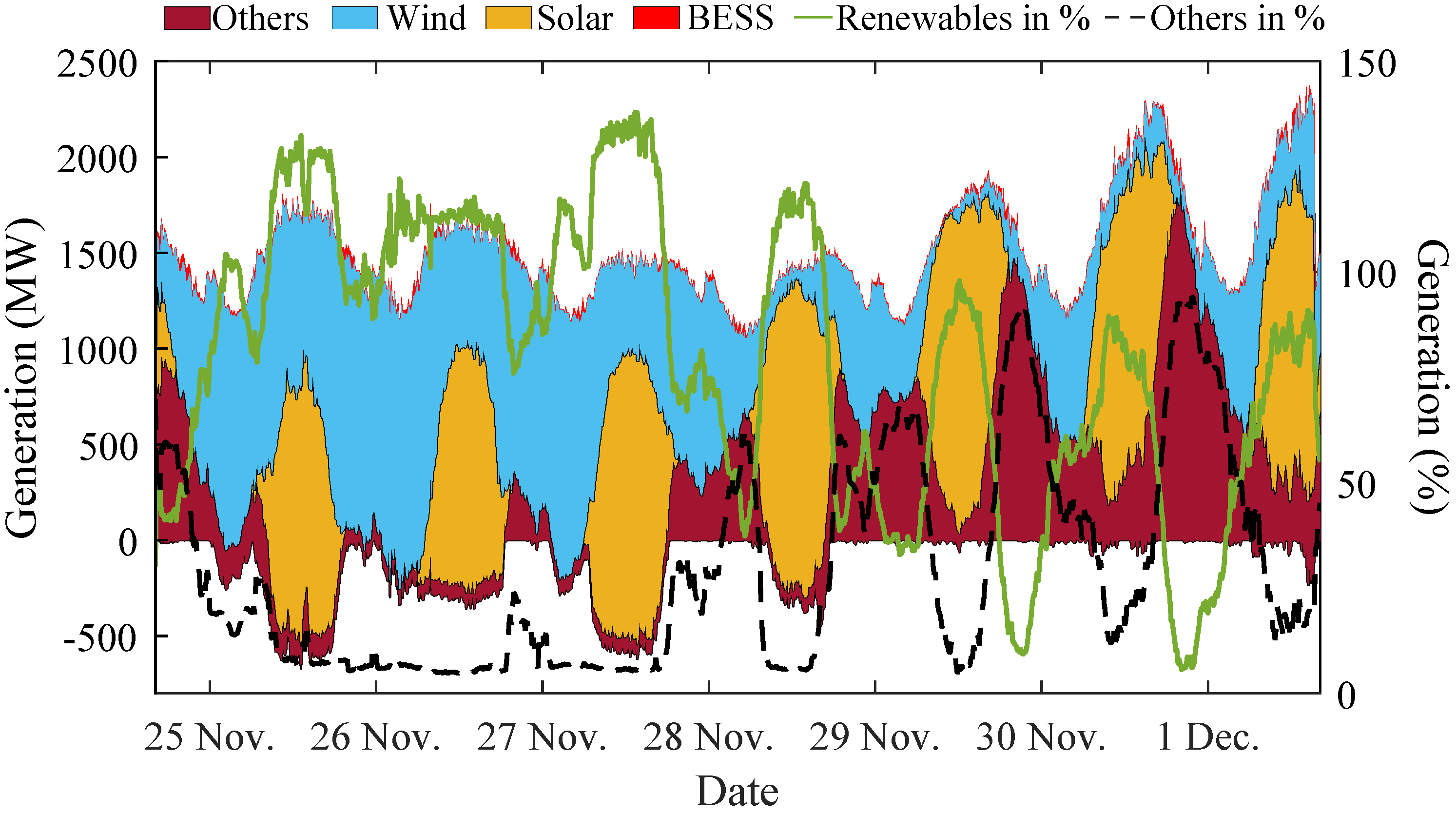

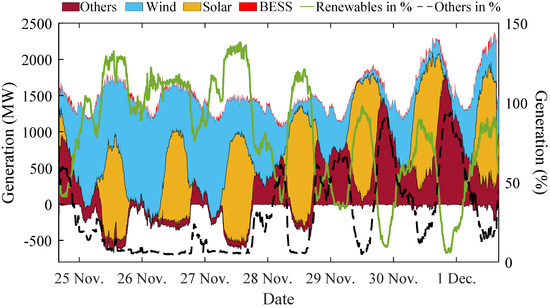

The integration of synchronous condenser into the transmission network has increased the secure use of renewable generation in the grid. At times, the participation of renewable generation is above 100%, meaning that South Australia exports clean energy to the rest of the NEM. For instance, Figure 7 shows the generation mix for a 7-day window, from 24 November to the 1 December [60]. During these days, renewable energy had a maximum participation of 137.9% (1904 MW) while gas-generating units and imports accounted for a 5.7% (78.9 MW). Nevertheless, due to the high variability of renewable energy resources, South Australia still requires the backup of traditional resources (gas) and imports to supply the demand during low renewable generation. For the same time frame, gas-generating units and imports accounted for a maximum participation of 94% (1856 MW) while renewable generation was only 7% (138.6 MW).

Figure 7.

Generation mix in South Australia for a 7-day window. High levels of variable renewable energy requires a portfolio of solutions to supply the demand (plot drawn with data from [60]).

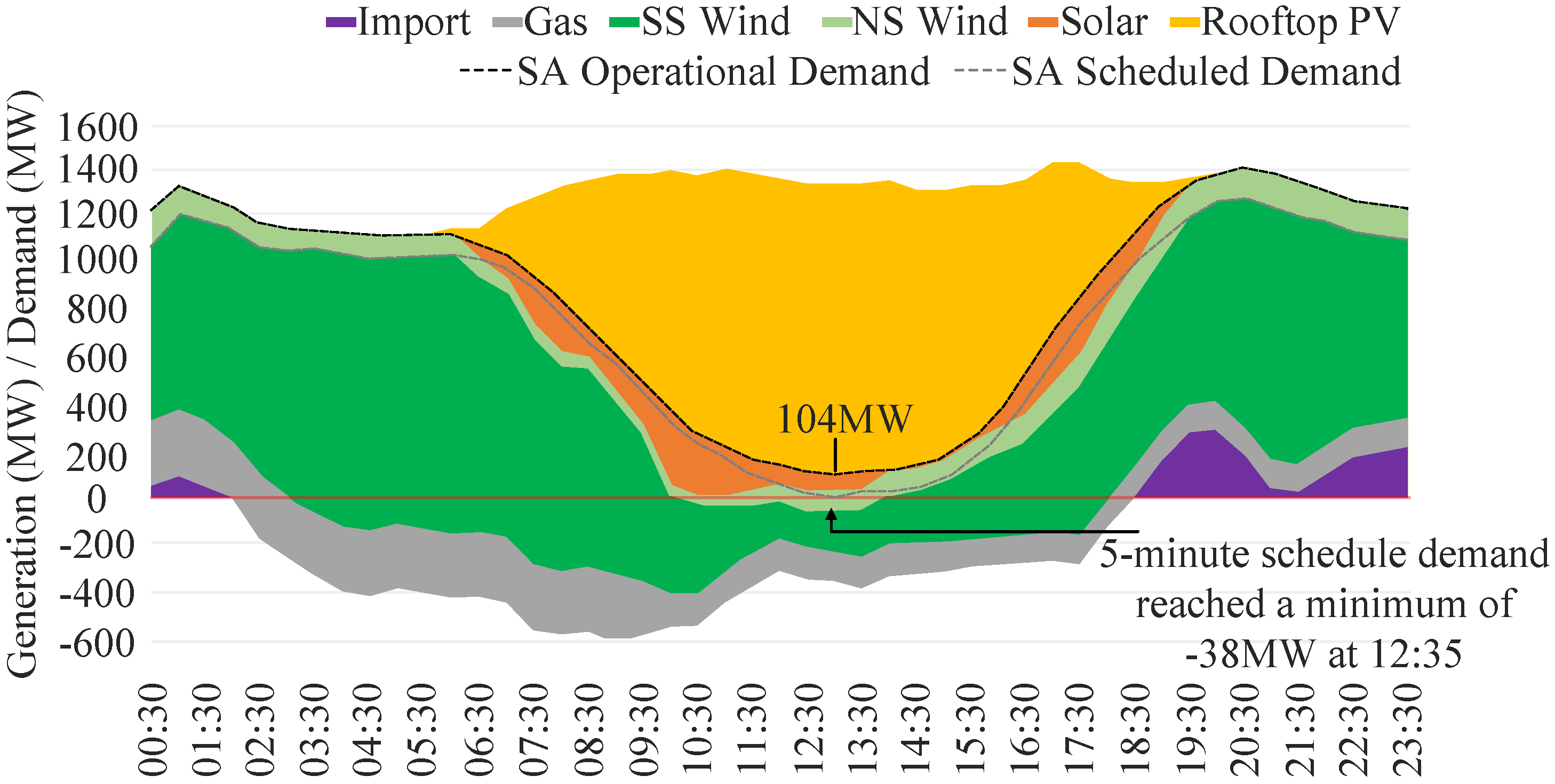

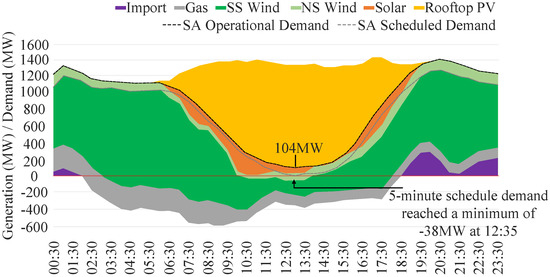

The operation of SynCons has also helped achieve new minimum operational demand records in the state as further gas-based units are backed off. According to AEMO, on Sunday 21 November 2021, the estimated rooftop PV provided 92% (1220 MW) of the region’s underlying demand, resulting in a minimum demand record of 104 MW from 12:30 to 1:00 p.m. [65]. This resulted in an excess of 38 MW of rooftop PV that was exported to other states. Demand and generation mixes on Sunday 21 November 2021 are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Negative scheduled electricity demand in South Australia, Sunday 21 November 2021 [65].

As distributed rooftop solar PV continues to grow, it is expected that minimum demand events will become more frequent in the near future. In order to better deal with these excesses of renewable and variable energy generation, additional technologies such as battery energy storage systems are also needed to increase the flexibility and operation of the system. Fast responses (ramps) are required to deal with power generation variability while continuing to provide inertia and system strength to the grid.

4.2. Battery Energy Storage Systems

4.2.1. Hornsdale Power Reserve—Largest Battery in Australia

The Hornsdale Power Reserve (HPR) was at the time of installation the largest grid-scale lithium-ion battery in the world. HPR is located near Jamestown, South Australia, and has a power rating of 150 MW and an energy storage of 194 MWh (refer to Figure 6). The project had a total capital expenditure of about A$170 million [66,67], and since its completion in November 2017 and expansion in September 2020, it has provided market benefits as well as technical services [68].

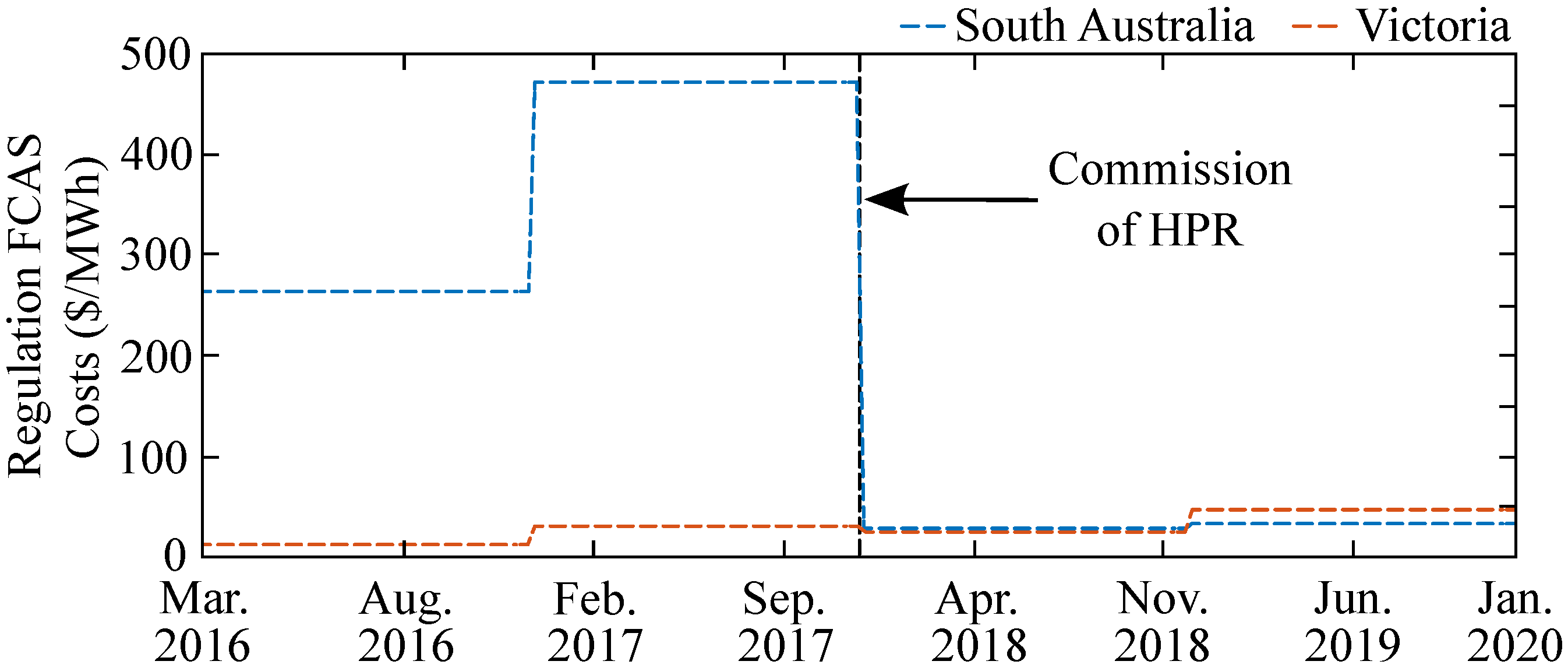

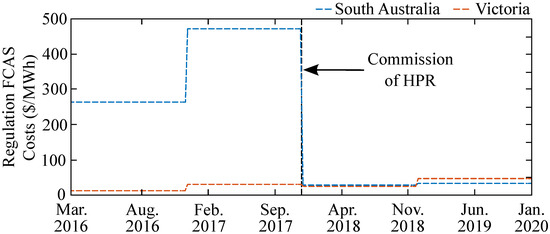

HPR has contributed in economically optimizing the use of generation asset by trading energy (arbitrage) in the wholesale energy market. Furthermore, HPR is registered in the Frequency Control Ancillary Services (FCAS) market. In particular, HPR participates in both regulation and contingency services to provide generation/demand balance and power system stabilization, respectively. For instance, as shown in Figure 9, HPR has helped to reduce in more than 91% the average yearly regulation FCAS costs for South Australia [68]. The participation of the battery has provided a cost-effective manner that competes with traditional generators, reducing prices to a level similar to the Victoria region.

Figure 9.

Decrease in regulation Frequency Control Ancillary Services (FCAS) costs due to the participation of the Hornsdale Power Reserve (HPR) battery (plot drawn with data from [68]).

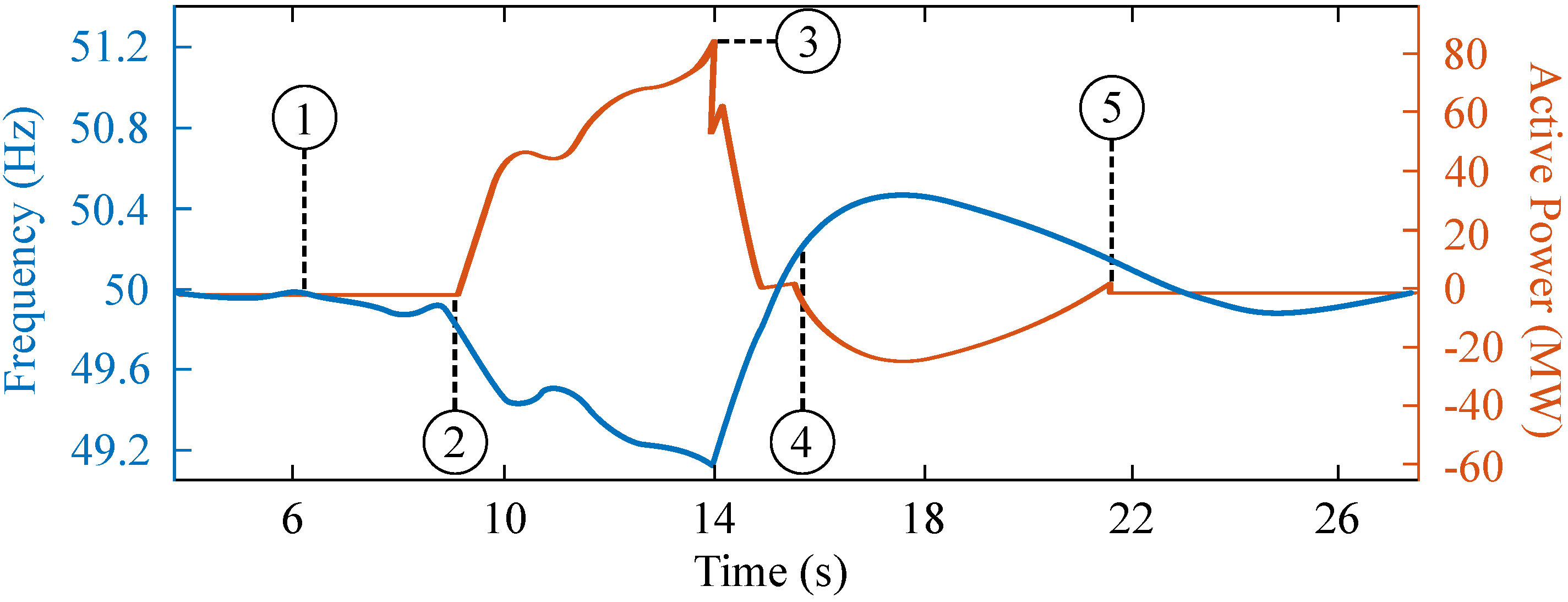

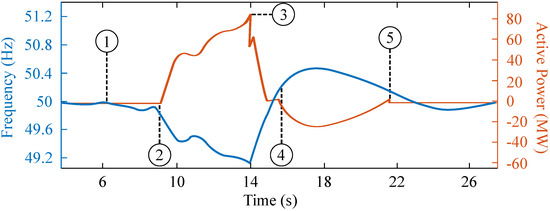

The grid-scale battery has also demonstrated its system security support during major contingency events. The fast frequency response (FFR) of HPR, contingency FCAS, has allowed operating the South Australian network under the loss of the Heywood interconnector between South Australia and Victoria. Figure 10 shows the frequency of the system and the active power support provided by the battery on the 25 August 2018 separation event [68]. The summary of events is as follows [69]:

Figure 10.

Frequency support of the Hornsdale Power Reserve (HPR) to 25 August 2018 separation event (plot drawn with data from [68]).

- At 13:11:39 the Queensland–New South Wales interconnector (QNI) trips, islanding Queensland from the rest of the power system;

- Frequency drops below the lower threshold (49.85 Hz). Consequently, HPR starts tracking its frequency droop curve and provides active power as part of its FFR response;

- The frequency falls to a minimum of 49.12 Hz, and HPR has an incremental response that rises to 84.3 MW. At 13:11:47, the Heywood interconnector trips due to the activation of its emergency control scheme, resulting in a rise in the South Australian grid’s frequency;

- HPR fast frequency response is activated when the upper frequency bound is exceeded (50.15 Hz), resulting in tracking its droop curve;

- Frequency returns to the normal operating range (50 ± 0.15 Hz) deactivating the FFR of the battery.

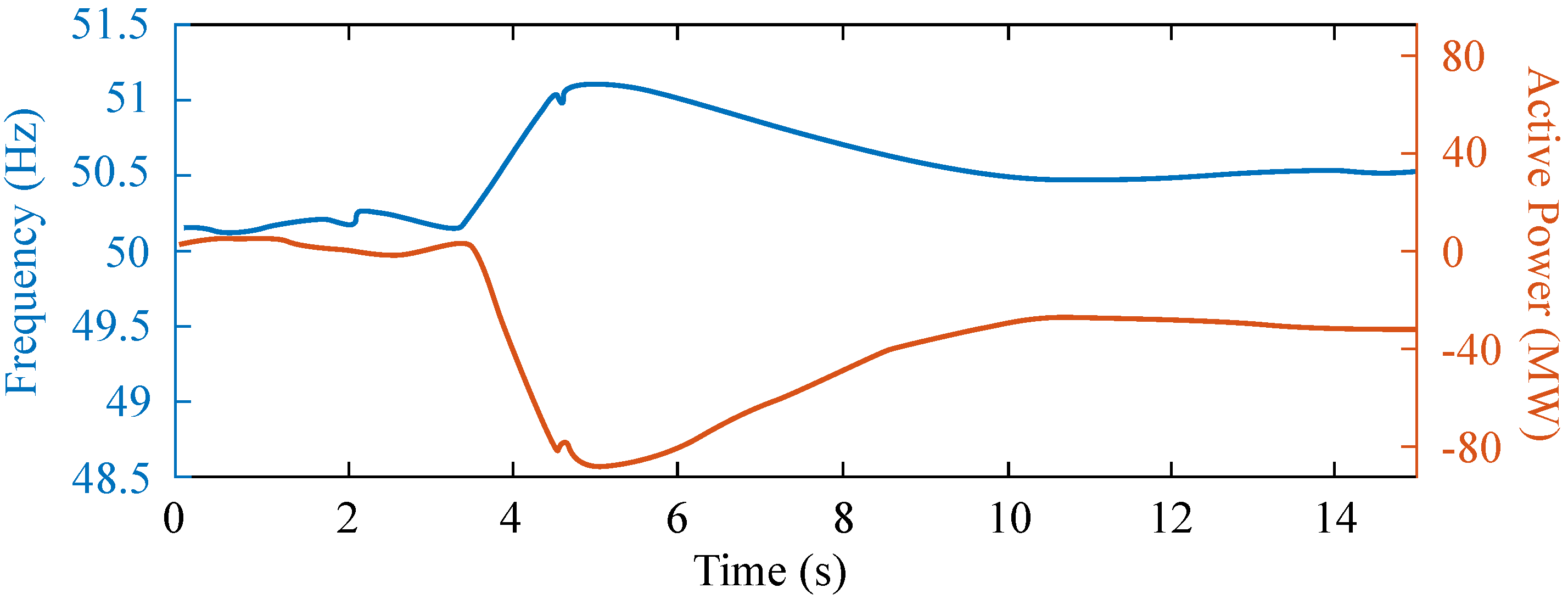

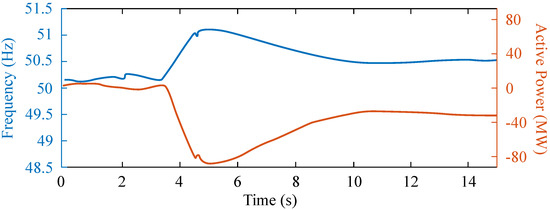

On 31 January 2020, the South Australia–Victoria Heywood interconnector tripped, and HPR response helped stabilize the South Australian network. Figure 11 shows the active power response of the battery to the frequency variation [68]. During this event, HPR transitioned from standby to 91 MW charging. The fast frequency response of BESS demonstrates its capability to reduce the severity of major disturbances while stabilizing the network.

Figure 11.

Frequency support of the Hornsdale Power Reserve (HPR) to 31 January 2020 separation event (plot drawn with data from [68]).

4.2.2. Dalrymple BESS—First Grid-Forming Battery

The Yorke Peninsula in South Australia is connected to the system through a radial 132 kV transmission system as shown in Figure 6 [70]. The area includes the Wattle Point wind farm (90 MW) on the lower part of the peninsula, which requires references from the system to operate. Disconnection of either the Hummocks to Ardrossan West 132 kV line or the Ardrossan West to Dalrymple 132 kV line resulted in the lost of local demand and Wattle Point generation. As a result, a A$30-million battery in Dalrymple was designed and commissioned to deliver a combination of network and market benefits [71].

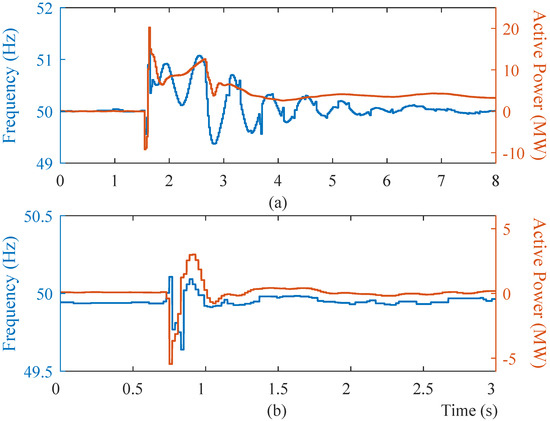

The Dalrymple 30 MW, 8 MWh battery energy storage system is the first grid-forming battery connected to the NEM. The control of the BESS is built on virtual synchronous generator technology, which replicates the behavior of synchronous machines (refer to Section 3.2). The battery strengthens the grid by providing synthetic inertia and high fault currents. Additionally, Dalrymple grid-forming BESS permits the islanded operation of the Yorke Peninsula, enhancing local reliability of supply. Other services of the battery include the fast frequency response (FFR), seamless black-start of the local distribution network, Frequency Control Ancillary Services (FCAS), and energy arbitrage.

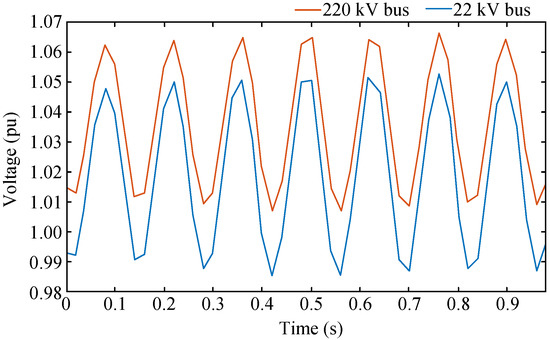

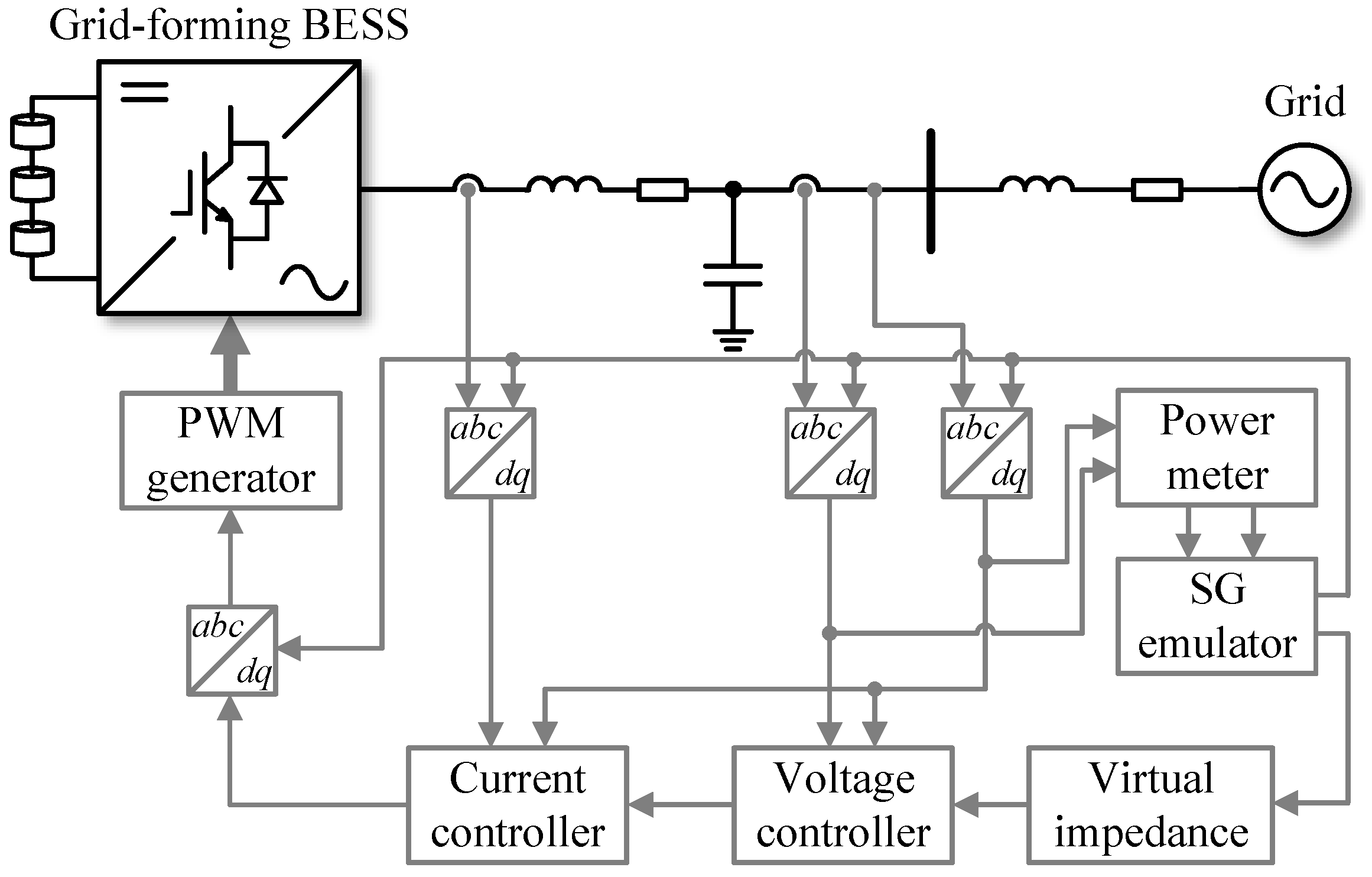

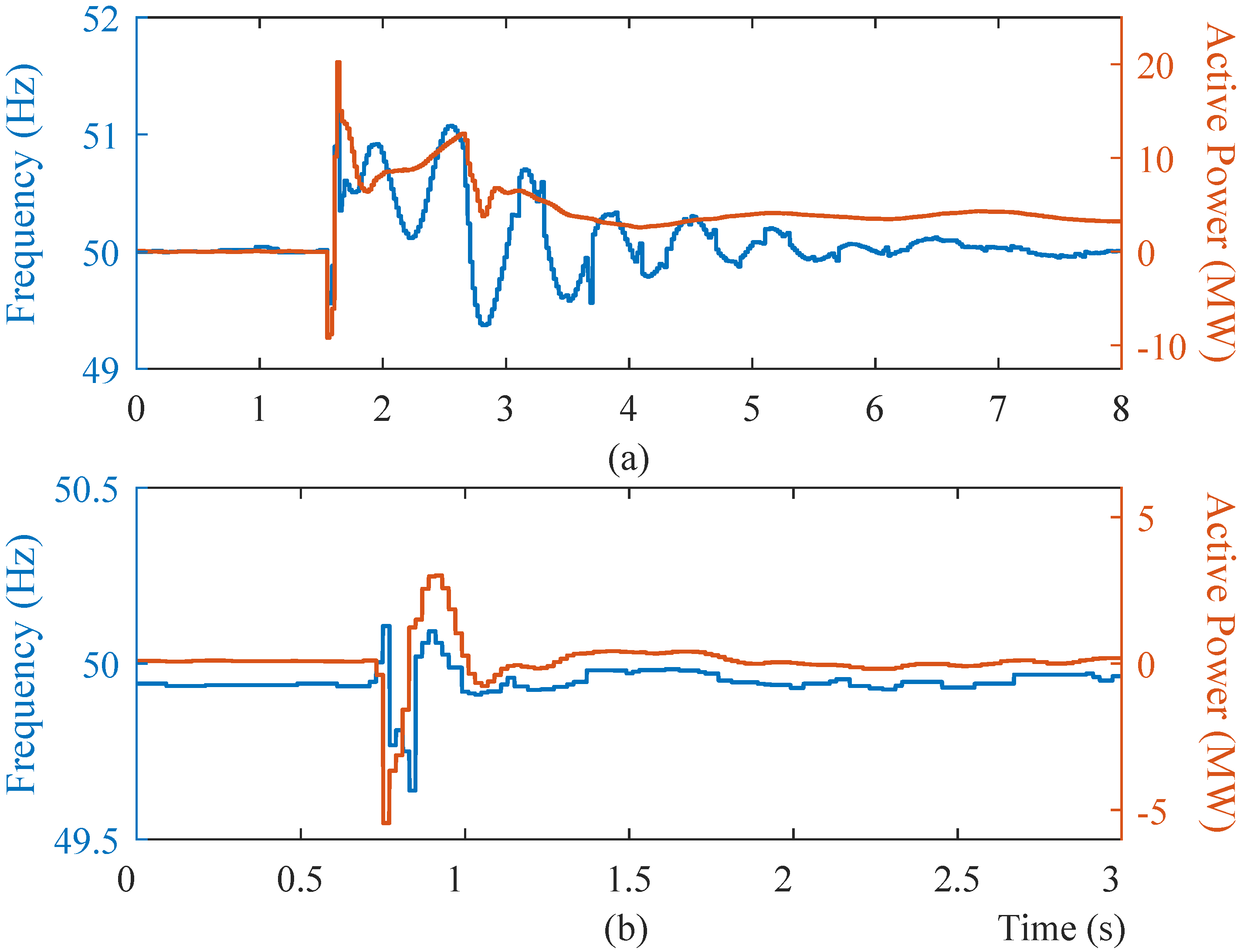

Since December 2018, the grid-forming BESS has experienced 29 operational system events. Figure 12 shows the response of BESS in terms of active power for two of these system events [70]. The upper plot provides the response of the battery for a single phase to ground fault at the Ardrossan West–Dalrymple 132-kV line. As it can be observed, the battery successfully rode through the fault. Furthermore, the operation of the battery allowed the Wattle Point wind farm to remain connected (59 MW). The bottom plot of Figure 12 shows how the battery also rode through a single phase to ground fault at the Bungama–Blyth West 275-kV line.

Figure 12.

Frequency support of Dalrymple to system events: (a) Single phase to ground fault at the Ardrossan West–Dalrymple 132 kV line. (b) Single phase to ground fault at the Bungama–Blyth West 275 kV line (plots drawn with data from [70]).

4.3. Looking Forward

The integration of synchronous condensers and grid-scale battery energy storage systems has demonstrated the benefits of these technologies in the transformation of the Australian grid. These technologies have had a significant impact on the NEM allowing large variable renewable energy participation, unprecedented minimum operational demands, and a reduction in costs for consumers. Further opportunities for energy storage systems may arise with combined the integration of renewables and storage in a single system and on the same dc-link (e.g., PV + storage, fuel cells + storage, etc.), but such solutions are yet to materialize at scale. Moreover, grid-forming capabilities can be designed in new IBR developments or implemented in existing projects to facilitate the integration of renewables and support the grid. Nevertheless, new operational tools and processes will be needed to operate the system with a higher penetration of variable renewable energy technologies. The maximum contribution from IBRs will be limited, and less than required, if timely actions to address variable and uncertain system conditions are not taken. Furthermore, suitable regulatory frameworks are required to streamline the deployment of alternative technologies and solutions. An IBR access procedure in line with the grid code is also expected to facilitate large-scale renewable integration. Market signals should align with system needs to ensure sufficient incentives for new investments or re-investment in existing assets.

5. Conclusions

The rapid uptake of both small-scale and large-scale renewable generation has resulted in new operational and planning challenges of power systems around the globe, and Australia is not the exception. In particular, the Australian National Electricity Market (NEM) has experienced continuous weakening due to the increasing participation of inverter-based resources (IBRs). Traditional IBR technologies do not provide essential services to the grid that are commonly provided by synchronous generators, which are being retired. System strength, inertia, firm capacity, and black-start capabilities are some of the functionalities that need to be available to the grid in order to maintain a secure operation.

A portfolio of diverse technologies that present cumulative capabilities is needed to overcome grid challenges while successfully integrating renewable energy generation. Synchronous condensers, battery energy storage systems, and grid-forming converters together with existing power system devices are observed as an option to flexibly transition to a more secure, reliable, and low emission power system. In this review, part of the Australian experience is provided, illustrating the successful integration of new solutions to overcome the challenges faced in a power system with a high share of IBRs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A.-V. and G.K.; methodology, F.A.-V. and Z.S.; software, F.A.-V. and Z.S.; validation, F.A.-V., Z.S. and S.J.; formal analysis, Z.S.; investigation, F.A.-V., Z.S. and G.K.; resources, G.K. and J.F.; data curation, F.A.-V. and Z.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A.-V. and S.J.; writing—review and editing, F.A.-V., G.K., S.J. and J.F.; visualization, F.A.-V., Z.S. and S.J.; supervision, G.K., S.J. and J.F.; project administration, G.K.; funding acquisition, F.A.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID) PFCHA/DOCTORADO BECAS CHILE/2017 72180176.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AEMO | Australian Energy Market Operator; |

| AVR | Active Voltage Regulation; |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System; |

| CSCR | Composite SCR; |

| DFIG | Doubly-Fed Induction Generator; |

| ERCOT | (U.S.) Electric Reliability Council of Texas; |

| FACT | Flexible AC Transmission Systems; |

| FCAS | Frequency Control Ancillary Services; |

| FFR | Fast Frequency Response; |

| GFL | Grid Following; |

| GFM | Grid Forming; |

| HPR | Hornsdale Power Reserve; |

| IBR | Inverter-Based Resource; |

| NEM | (Australian) National Electricity Market; |

| NSW | New South Wales; |

| PLL | Phase-Locked Loop; |

| PMSG | Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator; |

| PV | Photovoltaic; |

| QLD | Queensland; |

| REZ | Renewable Energy Zone; |

| RoCoF | Rate of Change of Frequency; |

| SA | South Australia; |

| SG | Synchronous Generator; |

| SCC | Short-Circuit Capacity; |

| SCR | Short-Circuit Ratio; |

| SSR | Subsynchronous Resonance; |

| SSSP | System Strength Service Provider; |

| STATCOM | Static Synchronous Compensator; |

| SVC | Static VAr Compensator; |

| SynCon | Synchronous Condenser; |

| TAS | Tasmania; |

| TNSP | Transmission Network Service Provider; |

| TSO | Transmission System Operator; |

| VIC | Victoria; |

| WECC | (U.S.) Western Electricity Coordinating Council; |

| WSCR | Weighted SCR. |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Investment; Technical Report; IEA: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA); Climate Policy Initiative (CPI). Global Landscape of Renewable Energy Finance; Technical Report; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Power System Dynamic Performance Committee (PSDP). Stability Definitions and Characterization of Dynamic Behavior in Systems with High Penetration of Power Electronic Interfaced Technologies; Technical Report PS-TR77; IEEE PES: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Denholm, P.; Sun, Y.; Mai, T. An Introduction to Grid Services: Concepts, Technical Requirements, and Provision from Wind; Technical Report NREL/TP-6A20-72578; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2019.

- Lee, N.; Flores-Espino, F.; Hurlbut, D. Renewable Energy Zone (REZ) Transmission Planning Process: A Guidebook for Practitioners; Technical Report; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Denver, CO, USA, 2017.

- Hadavi, S.; Mansour, M.Z.; Bahrani, B. Optimal Allocation and Sizing of Synchronous Condensers in Weak Grids With Increased Penetration of Wind and Solar Farms. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2021, 11, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, L.; Pagani, G.A.; Pelacchi, P.; Poli, D.; Aiello, M. Sizing and Siting of Large-Scale Batteries in Transmission Grids to Optimize the Use of Renewables. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2017, 7, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soong, T.; Bessegato, L.; Meng, L.; Wu, T.; Hasler, J.-P.; Ingeström, G.; Kheir, J. Capability and Flexibility of Energy Storage Enhanced STATCOMs in Low Inertia Power Grids. In 2020 CIGRE Session; CIGRE: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Blakers, A.; Stocks, M.; Lu, B.; Cheng, C.; Stocks, R. Pathway to 100% Renewable Electricity. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2019, 9, 1828–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australia Energy Market Operator (AEMO); Energy Networks Australia (ENA). Open Energy Networks; Technical Report; AEMO and ENA: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Electricity Market Operator (AEMO). NEM Generation Information; Technical Report; AEMO: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). Fact Sheet: The National Electricity Market; Technical Report; AEMO: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Electricity Market Operator (AEMO). Renewable Integration Study: Stage 1 Report; Technical Report; AEMO: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). 2020 Integrated System Plan; Technical Report; AEMO: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC). Short-Circuit Modeling and System Strength; White Paper; NERC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- CIGRE Joint Working Group C4/C6.35/CIRED. Modelling of Inverter-Based Generation for Power System Dynamic Studies; Technical Brochure 727; CIGRE: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Achilles, S.; Miller, N.; Larsen, E.; MacDowell, J. Stable Renewable Plant Voltage and Reactive Power Control. NERC’s Website. 2014. Available online: https://www.nerc.com/comm/Other/essntlrlbltysrvcstskfrcDL/VoltVarControl_Weaksys%20ERSTF%20JMM%20GE_0612.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC). Essential Reliability Services Task Force Measures Framework Report; Technical Report; NERC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tielens, P.; Hertem, D.V. The relevance of inertia in power systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Krishnaswami, H.; Yuan, G.; Huang, R. Ubiquitous Power Electronics in Future Power Systems: Recommendations to Fully Utilize Fast Control Capabilities. IEEE Electrific. Mag. 2020, 8, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Kavasseri, R.; Miao, Z.L.; Zhu, C. Modeling of DFIG-Based Wind Farms for SSR Analysis. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2010, 25, 2073–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Blaabjerg, F. Harmonic Stability in Power Electronic-Based Power Systems: Concept, Modeling, and Analysis. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 2019, 10, 2858–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoke, A.; Gevorgian, V.; Shah, S.; Koralewicz, P.; Kenyon, R.W.; Kroposki, B. Island Power Systems With High Levels of Inverter-Based Resources: Stability and Reliability Challenges. IEEE Electrific. Mag. 2021, 9, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroposki, B.; Johnson, B.; Zhang, Y.; Gevorgian, V.; Denholm, P.; Hodge, B.-M.; Hannegan, B. Achieving a 100% Renewable Grid: Operating Electric Power Systems with Extremely High Levels of Variable Renewable Energy. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2017, 15, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Yang, G.; Nielsen, A.H.; Rønne-Hansen, P. Impact of VSC Control Strategies and Incorporation of Synchronous Condensers on Distance Protection Under Unbalanced Faults. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 1108–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). System Strength Impact Assessment Guidelines; Technical Report 1; AEMO: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Custer, G. Inverter Protection and Ride-Through: Today’s Photovoltaic and Energy Storage Inverters. IEEE Electrific. Mag. 2021, 9, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Miao, Z. Wind in Weak Grids: 4 Hz or 30 Hz Oscillations? IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 5803–5804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, L.; Miao, Z. Wind in Weak Grids: Low-Frequency Oscillations, Subsynchronous Oscillations, and Torsional Interactions. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Xiong, X.; Taul, M.G.; Blaabjerg, F. Enhancing Transient Stability of PLL-Synchronized Converters by Introducing Voltage Normalization Control. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2021, 11, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Boroyevich, D.; Mattavelli, P.; Shen, Z.; Burgos, R. Influence of Phase-Locked Loop on Input Admittance of Three-Phase Voltage-Source Converters. In Proceedings of the 2013 Twenty-Eighth Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Long Beach, CA, USA, 17–21 March 2013; pp. 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matevosyan, J. Survey of Grid-Forming Inverter Applications. ESIG’s Website. 2021. Available online: https://globalpst.org/wp-content/uploads/Survey-of-Grid-Forming-Inverter-Applications-Julia-Matevosyan.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Rosso, R.; Wang, X.; Liserre, M.; Lu, X.; Engelken, S. Grid-Forming Converters: Control Approaches, Grid-Synchronization, and Future Trends—A Review. IEEE Open J. Ind. Appl. 2021, 2, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafti, H.D.; Konstantinou, G.; Fletcher, J.; Callegaro, L.; Farivar, G.G.; Pou, J. Control of Distributed Photovoltaic Inverters for Frequency Support and System Recovery. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Meier, A. Integration of Renewable Generation in California: Coordination Challenges in Time and Space. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Electrical Power Quality and Utilisation, Lisbon, Portugal, 17–19 October 2011; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Proceso de Planificación Energética de Largo Plazo [Long-Term Energy Planning Process]; Technical Report Final Report; Ministerio de Energía: Santiago, Chile, 2018.

- Wind Turbines Connected to Grids with Voltages below 100 kV: Technical Regulations for the Properties and the Control of Wind Turbines; Technical Regulations TF 3.2.6; Eltra and Elkraft System: Denmark, 2003; Available online: https://nanopdf.com/download/wind-turbines-connected-to-grids-with-voltages_pdf (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Grid Code: High and Extra High Voltage; Technical Report Status: 1; E.ON Netz GmbH: Bayreuth, Germany, 2006.

- Adams, J.; Carter, C.; Huang, S.H. ERCOT Experience with Sub-Synchronous Control Interaction and Proposed Remediation; PES T&D 2012; IEEE: Orlando, FL, USA, 2012; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Schmall, J.; Conto, J.; Adams, J.; Zhang, Y.; Carter, C. Voltage Control Challenges on Weak Grids with High Penetration of Wind Generation: ERCOT Experience. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Power & Energy Soc. General Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–26 July 2012; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xie, X.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, H. Investigation of SSR in Practical DFIG-Based Wind Farms Connected to a Series-Compensated Power System. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2015, 30, 2772–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xie, X.; He, J.; Xu, T.; Yu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, C. Subsynchronous Interaction Between Direct-Drive PMSG Based Wind Farms and Weak AC Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 32, 4708–4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). Black System South Australia 28 September 2016; Technical Report; AEMO: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC). 1200 MW Fault Induced Solar Photovoltaic Resource Interruption; Disturbance Report Version 1.1; NERC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC). 900 MW Fault Induced Solar Photovoltaic Resource Interruption; Disturbance Report; NERC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yilun, L. Analysis of causes and solutions of a high-frequency oscillation accident in a wind farm. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2021, 49, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, N.; Badrzadeh, B.; Halley, A.; Louis, A.; Jalali, A. Operational Manifestation of Low System Strength Conditions—Australian Experience; CIGRE Centennial Session; CIGRE: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Transgrid. New South Wales Transmission Annual Planning Report; Technical Report; Transgrid: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Katsuya, Y.; Mitani, Y.; Tsuji, K. Power System Stabilization by Synchronous Condenser with Fast Excitation Control. In Proceedings of the PowerCon 2000—2000 International Conference on Power System Technology, Perth, WA, Australia, 4–7 December 2000; pp. 1563–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, A. Power moves: Synchronous condensers are an old technology enjoying a new lease of life, enabling more renewables to connect to the grid. Engineer 2021, 302, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- ABB. ABB Synchronous Condensers Manage Smooth Grid Integration for One of Australia’s Largest Solar Farms. ABB’s Website. 2020. Available online: https://new.abb.com/news/detail/71901/abb-synchronous-condensers-manage-smooth-grid-integration-for-one-of-australias-largest-solar-farms (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- ElectraNet. Transmission Annual Planning Report; Technical Report; ElectraNet: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2021; Available online: https://www.electranet.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021-ElectraNet-Transmission-Annual-Planning-Report.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). In Sync: How the Revival of 100 Year Old Technology Supports the Power System. AEMO’s Website. 2019. Available online: https://www.aemo.com.au/newsroom/energy-live/synchronous-condensers (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). Victorian Annual Planning Report; Technical Report; AEMO: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Powerlink. Transmission Annual Planning Report; Technical Report; Powerlink: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2021; Available online: https://www.powerlink.com.au/sites/default/files/2021-10/Transmission%20Annual%20Planning%20Report%202021%20-%20Overview_0.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Alipoor, J.; Miura, Y.; Ise, T. Power System Stabilization Using Virtual Synchronous Generator With Alternating Moment of Inertia. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Power Electron. 2015, 3, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Andalib-Bin-Karim, C.; Li, W.; Mitolo, M.; Shabbir, M.N.S.K. Adaptive Virtual Impedance-Based Reactive Power Sharing in Virtual Synchronous Generator Controlled Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 57, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yang, M.; Li, H.; Yang, P.; Xu, L.; Coelho, E.A.; Guerrero, J.M. Modeling and Stability Analysis of LCL-Type Grid-Connected Inverters: A Comprehensive Overview. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 114975–115001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). Renewable Energy Integration—SWIS Update; Technical Report; AEMO: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OpenNEM. Energy: South Australia. OpenNEM’s Website. 2021. Available online: https://opennem.org.au/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). System Strength Requirements Methodology, System Strength Requirements and Fault Level Shortfalls; Technical Report 1; AEMO: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Appleby, S.; Rositano, P. Addressing the System Strength Gap in SA; Economic Evaluation Report; ElectraNet: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ElectraNet. Main Grid System Strength Project; Contingent Project Application; ElectraNet: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). Transfer Limit Advice—System Strength in SA and Victoria; Technical Report; AEMO: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). Negative Electricity Demand in South Australia. AEMO’s Website. 2021. Available online: https://aemo.com.au/newsroom/news-updates/negative-electricity-demand-in-south-australia (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Neoen. Registration Document; Technical Report; Neoen: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Neoen. Universal Registration Document; Technical Report; Neoen: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aurecon. Hornsdale Power Reserve: Year 2 Technical and Market Impact Case Study; Technical Report; Aurecon: Docklands, VIC, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). Queensland and South Australia System Separation on 25 August 2018; Final Report; AEMO: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ElectraNet. ESCRI-SA Battery Energy Storage Project; Operational Report 4; ElectraNet: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ElectraNet. ESCRI-SA Project Summary Report; Technical Report; ElectraNet: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).