Rheological Properties of Crude Oil and Produced Emulsion from CO2 Flooding

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Simulated Fluid

2.3. Viscosity–Temperature Properties and Yield Point Measurement

2.4. Emulsion Stability Test

2.5. Demulsification Test

3. Results and Discussion

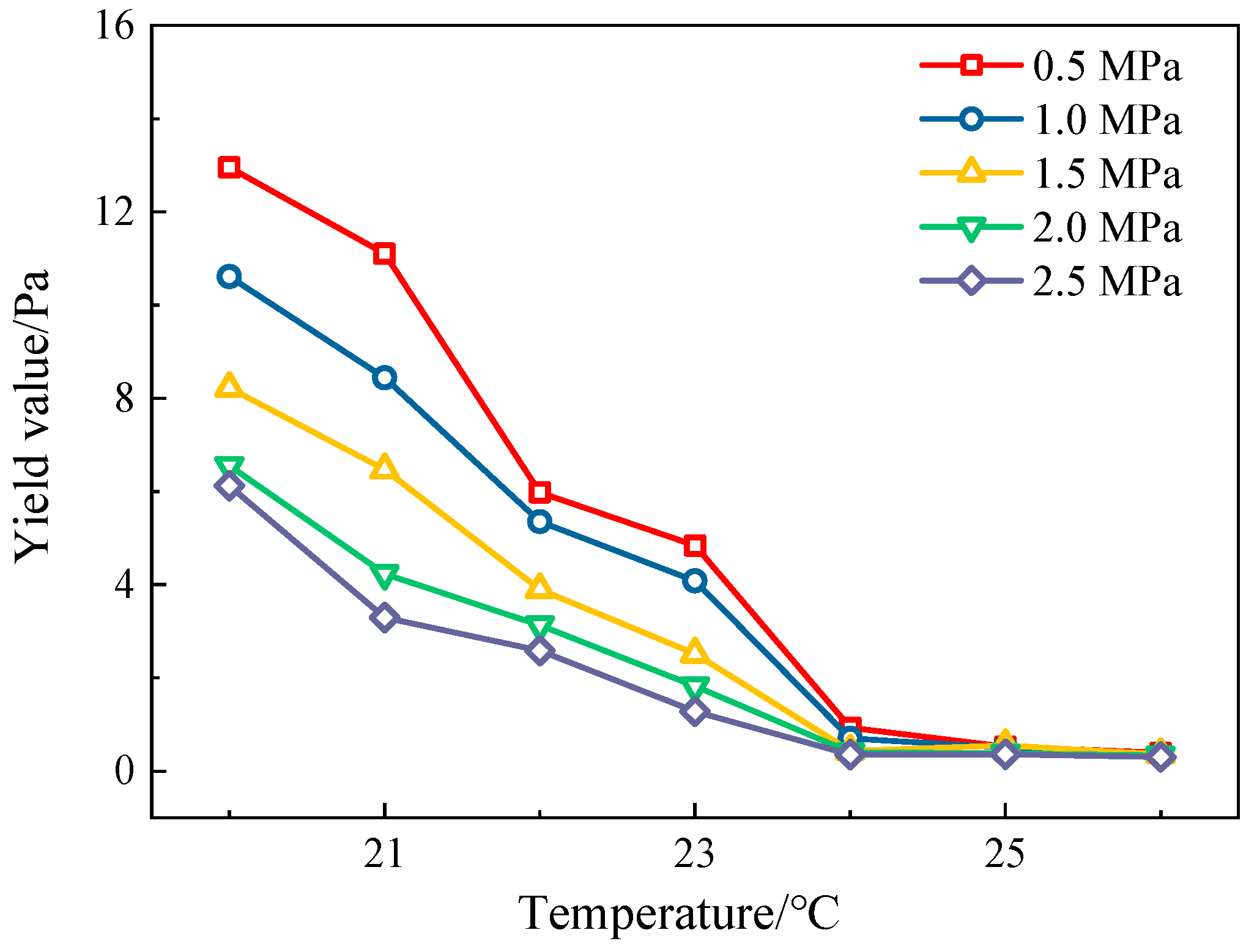

3.1. Viscosity–Temperature Characteristics and Pressure-Dependent Yield Value of CO2-Dissolved Crude Oil Under Pressure

3.2. The Law Between the Stability and Rheology of CO2-Dissolved Gas and Produced Fluid

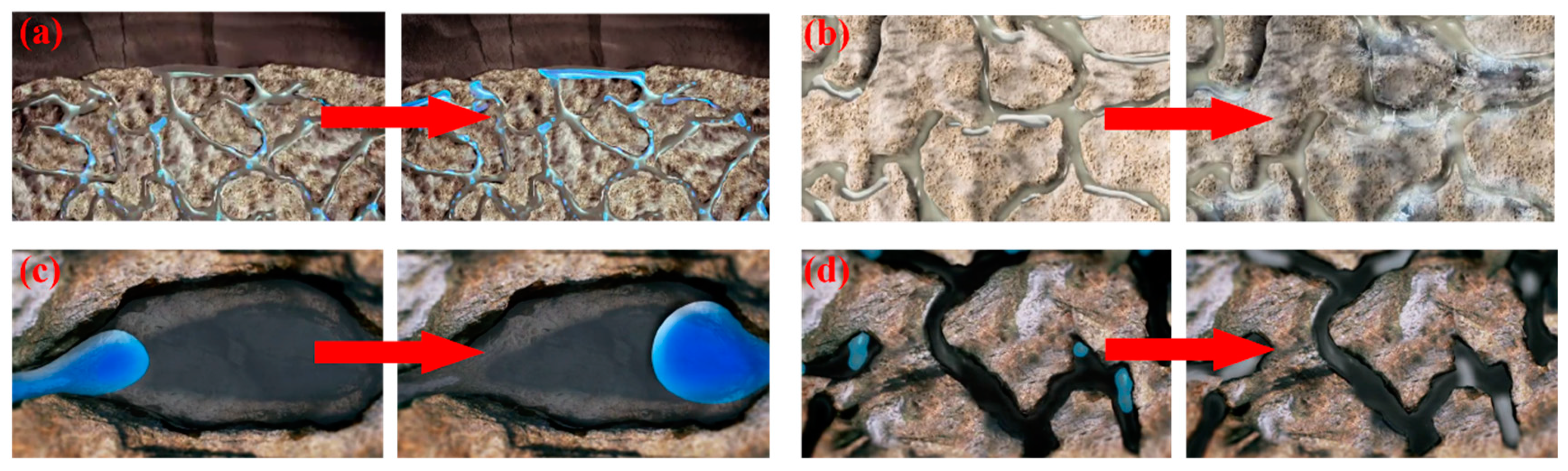

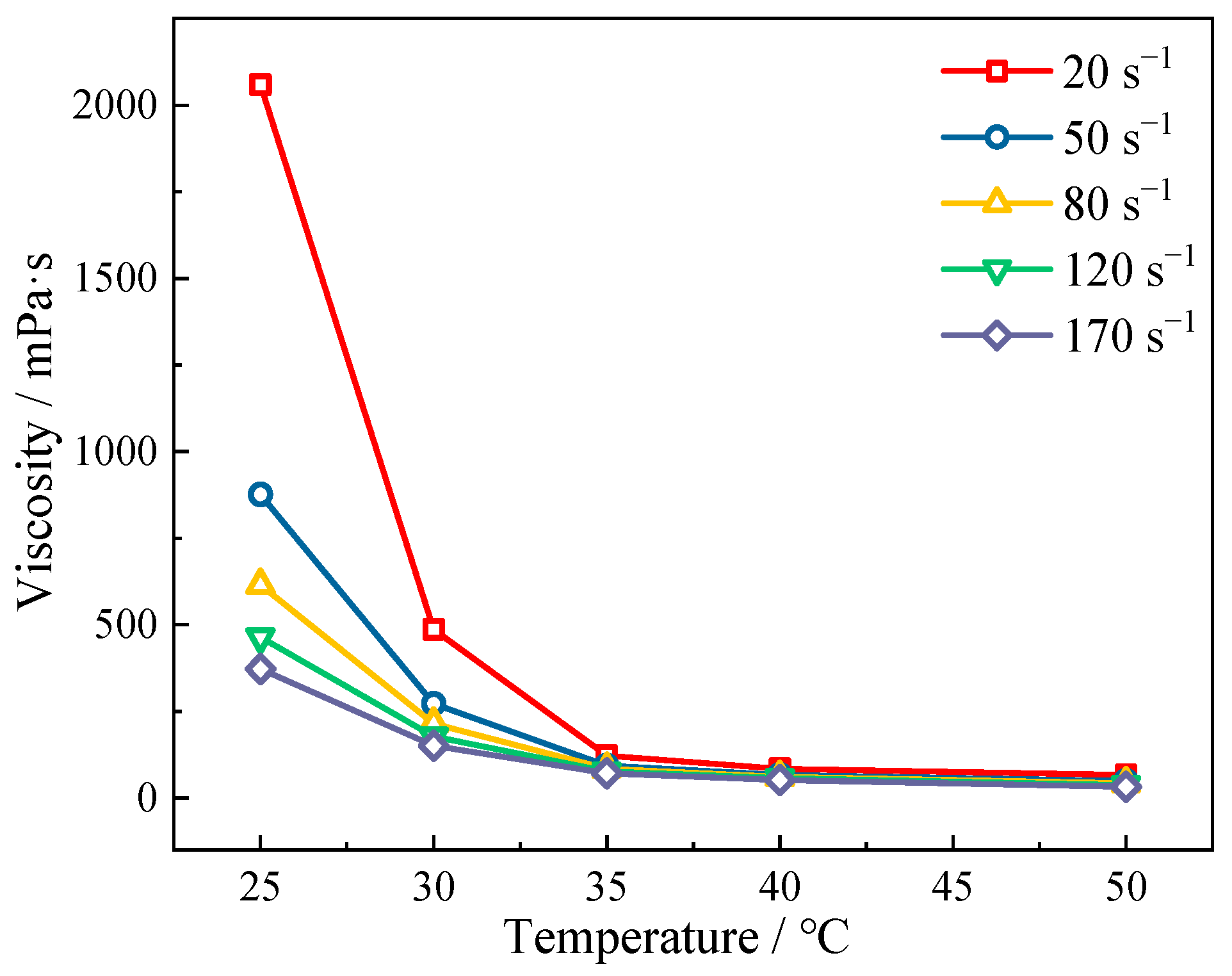

3.2.1. Viscosity–Temperature Characteristics and Stability of Emulsion

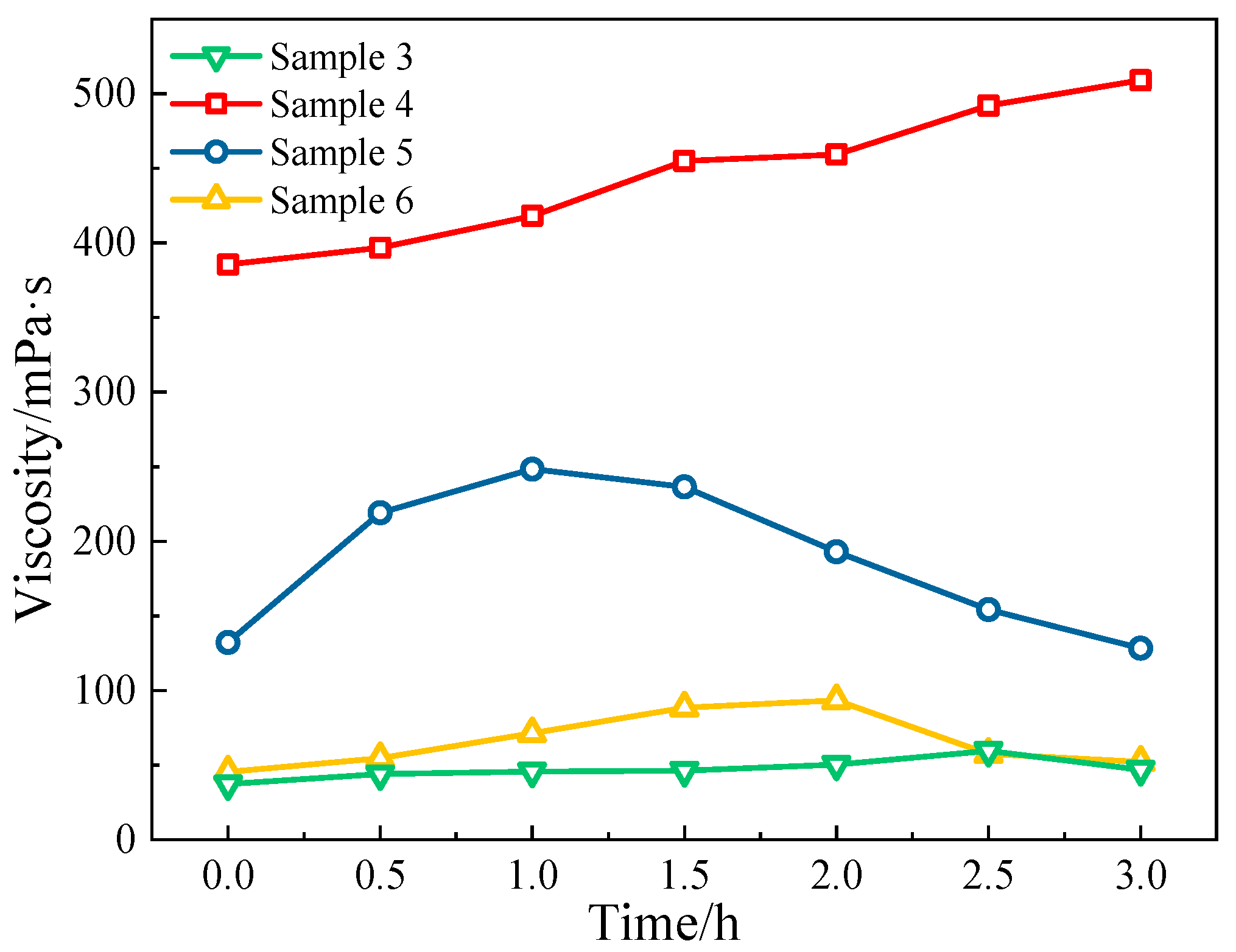

3.2.2. The Relationship Between the Stability and Rheology of CO2-Dissolved Gas and Produced Fluid

3.3. Demulsifier Screening and Demulsification Effect

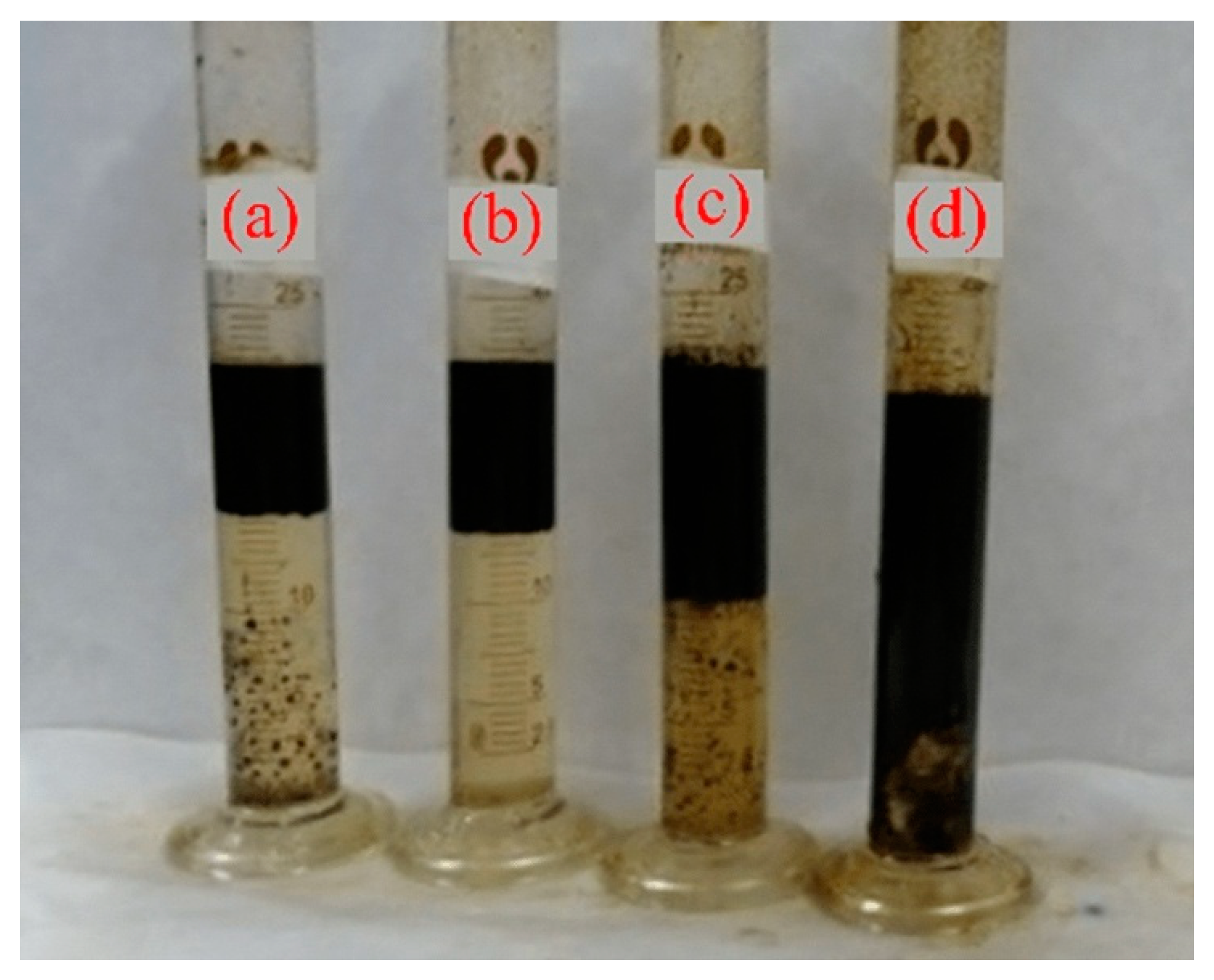

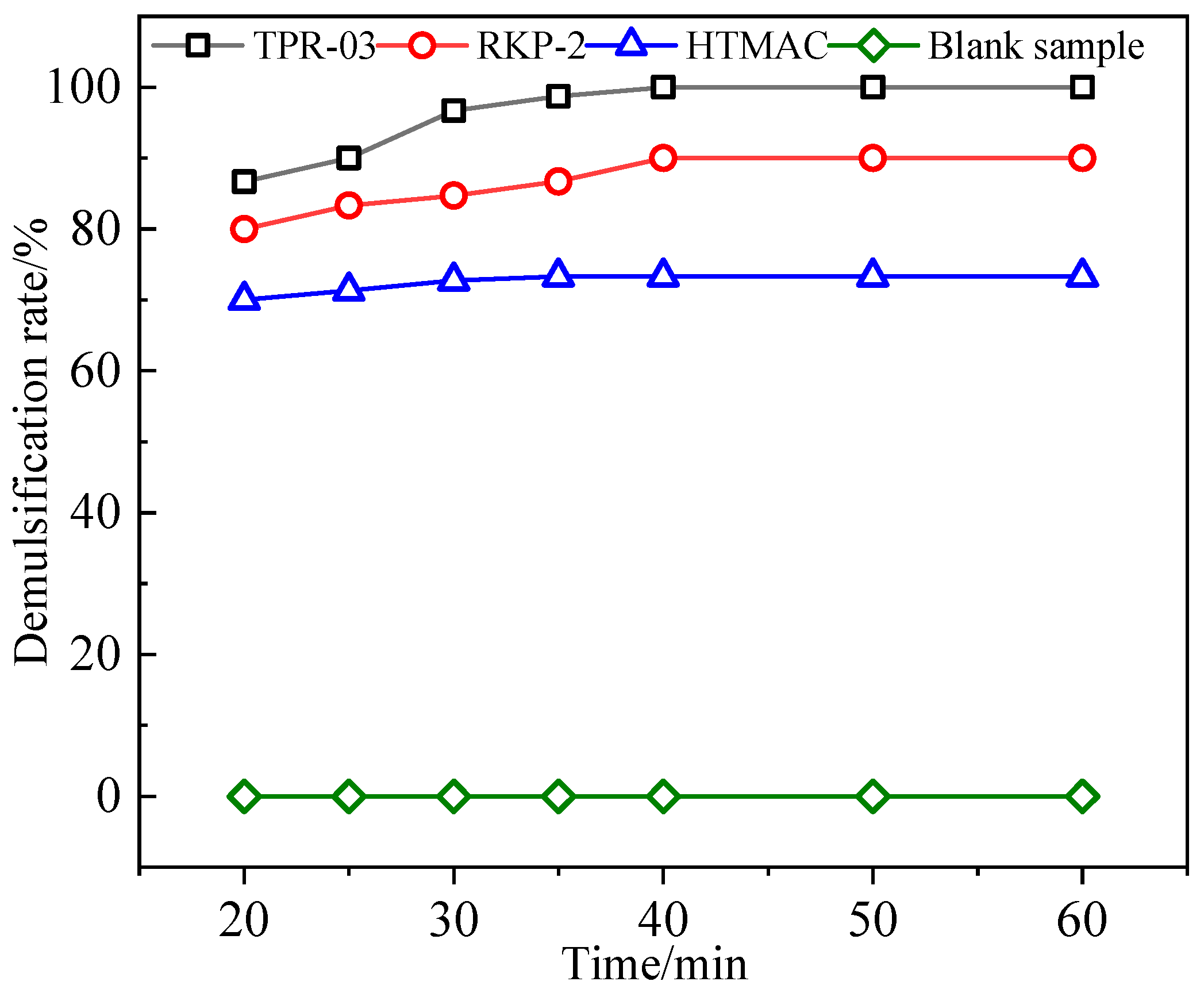

3.3.1. Selection of Demulsifiers

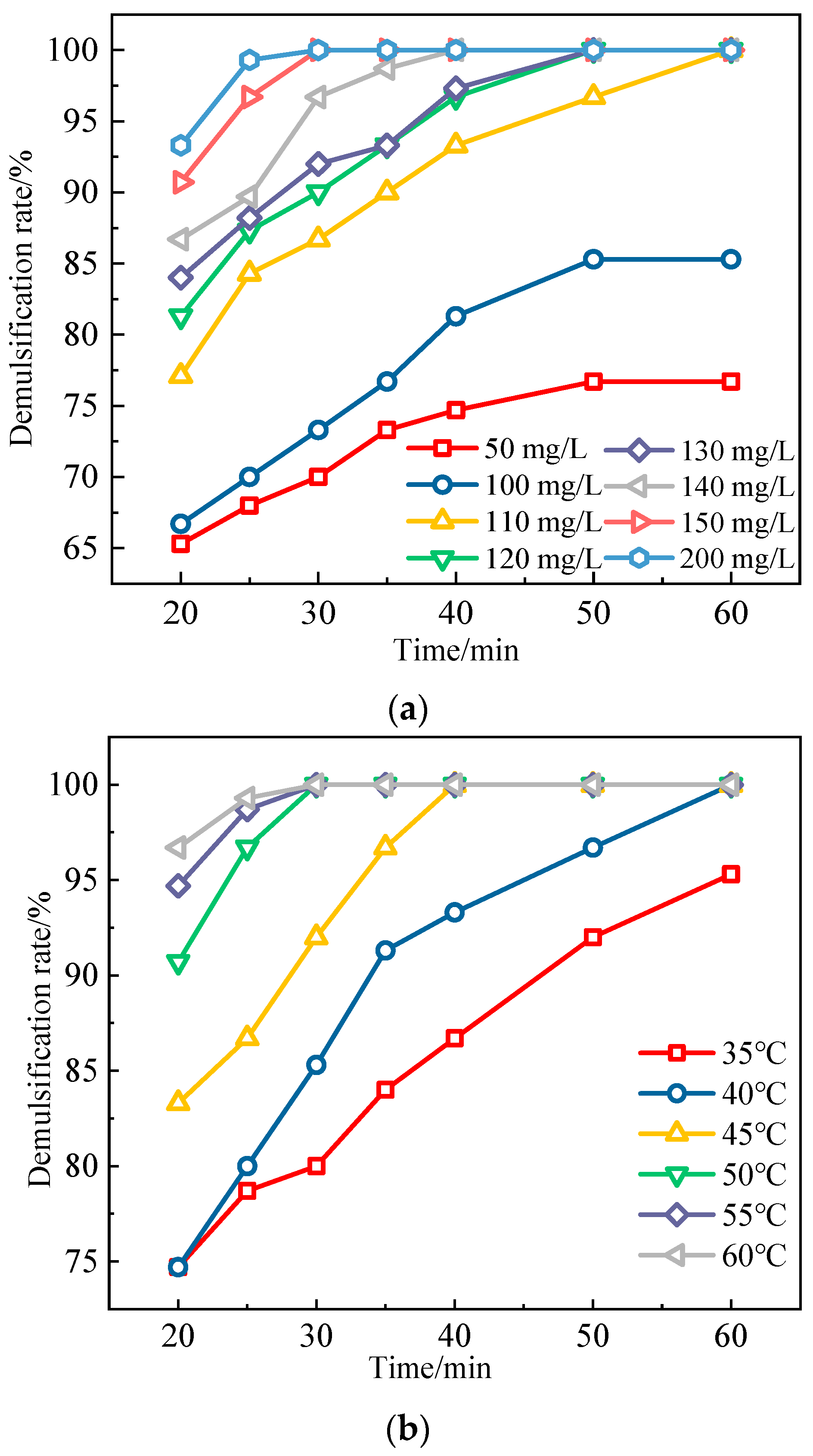

3.3.2. Selection of Demulsification Temperature and Dosage of Additives

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mon, M.T.; Tansuchat, R.; Yamaka, W. CCUS Technology and Carbon Emissions: Evidence from the United States. Energies 2024, 17, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gür, T.M. Carbon dioxide emissions, capture, storage and utilization: Review of materials, processes and technologies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2022, 89, 100965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakher, S.; Imqam, A. Application of carbon dioxide injection in shale oil reservoirs for increasing oil recovery and carbon dioxide storage. Fuel 2020, 265, 116944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruina, X.; Tiancheng, J.; Taojie, L.; JIANG, P. Research progress on heat and mass transfer in carbon geological storage and enhanced oil/gas/geothermal recovery technology. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2022, 62, 634–654. [Google Scholar]

- Roussanaly, S.; Grimstad, A.-A. The Economic Value of CO2 for EOR Applications. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 7836–7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Rui, Z. A Storage-Driven CO2 EOR for a Net-Zero Emission Target. Engineering 2022, 18, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martirosyan, A.V.; Ilyushin, Y.V.; Afanaseva, O.; Kukharova, T.V.; Asadulagi, M.-A.M.; Khloponina, V. Development of an Oil Field’s Conceptual Model. Int. J. Eng. 2025, 38, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajzadeh, R.; Eftekhari, A.A.; Dafnomilis, G.; Lake, L.W.; Bruining, J. On the sustainability of CO2 storage through CO2—Enhanced oil recovery. Appl. Energy 2020, 261, 114467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.; Halland, E. Perspective of CO2 for Storage and Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) in Norwegian North Sea. Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 7042–7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imurec, N.G.-M.; Novak-Mavar, K.; Maji, M. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS): Technology, Projects and Monitoring Review. Min.-Geol.-Pet. Eng. Bull. 2018, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, B.; Duncan, I.J. Reservoir simulation of carbon storage associated with CO2 EOR in residual oil zones, San Andres formation of West Texas, Permian Basin, USA. Energy 2019, 167, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Ma, D.; Li, J.; Zhou, T.; Ji, Z.; Han, H. Progress and prospects of carbon dioxide capture, EOR-utilization and storage industrialization. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2022, 49, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyinla, D.S.; Leggett, S.; Badrouchi, F.; Emadi, H.; Adamolekun, O.J.; Akinsanpe, O.T. A comprehensive review of the potential of rock properties alteration during CO2 injection for EOR and storage. Fuel 2023, 353, 129219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isah, A.; Arif, M.; Hassan, A.; Mahmoud, M.; Iglauer, S. A systematic review of Anhydrite-Bearing Reservoirs: EOR Perspective, CO2-Geo-storage and future research. Fuel 2022, 320, 123942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edouard, M.N.; Okere, C.J.; Ejike, C.; Dong, P.; Suliman, M.A. Comparative numerical study on the co-optimization of CO2 storage and utilization in EOR, EGR, and EWR: Implications for CCUS project development. Appl. Energy 2023, 347, 121448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Jun, S.; Na, Y.; Kim, K.; Jang, Y.; Wang, J. Geomechanical challenges during geological CO2 storage: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 456, 140968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozowe, W.; Daramola, G.O.; Ekemezie, I.O. Innovative approaches in enhanced oil recovery: A focus on gas injection synergies with other EOR methods. Magna Sci. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 11, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snæbjörnsdóttir, S.Ó.; Sigfússon, B.; Marieni, C.; Goldberg, D.; Gislason, S.R.; Oelkers, E.H. Carbon dioxide storage through mineral carbonation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Jha, N.K.; Pal, N.; Keshavarz, A.; Hoteit, H.; Sarmadivaleh, M. Recent advances in carbon dioxide geological storage, experimental procedures, influencing parameters, and future outlook. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 225, 103895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Niu, J.; Zhang, K. Current Status and Outlook of CCUS Industry in China. In Annual Report on China’s Petroleum, Gas and New Energy Industry (2022–2023); China International United Petroleum, Chemicals Co., Ltd., Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Peking University, Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Bump, A.; Hosseini, S.A.; Meckel, T.A.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H. A comprehensive review of efficient capacity estimation for large-scale CO2 geological storage. Gas Sci. Eng. 2024, 126, 205339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.-X.; Li, S.-Y.; Li, B.-F.; Chen, D.-Q.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Li, Z.-M. A review of development methods and EOR technologies for carbonate reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2020, 17, 990–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-X.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.-J.; Gao, M.; Wang, Z.-B.; Liu, W.-L. Status and progress of worldwide EOR field applications. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 193, 107449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samnioti, A.; Gaganis, V. Applications of Machine Learning in Subsurface Reservoir Simulation—A Review—Part II. Energies 2023, 16, 6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pang, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, M.; Hui, G. Robust prediction for CH4/CO2 competitive adsorption by genetic algorithm pruned neural network. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 234, 212618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wei, C.; Wang, B.; Yang, J.; Xu, X.; Wu, S.; Huang, S. Well performance prediction based on Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, S.; Al-Shargabi, M.; Wood, D.A.; Mehrad, M.; Rukavishnikov, V.S. Carbon dioxide sequestration through enhanced oil recovery: A review of storage mechanisms and technological applications. Fuel 2024, 366, 131313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, A.; Kalam, S.; Kamal, M.S.; Hussain, S.S.; Solling, T. EOR Perspective of microemulsions: A review. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Elakneswaran, Y.; Shimokawara, M.; Kato, Y.; Kitamura, R.; Hiroyoshi, N. Impact of the Temperature, Homogenization Condition, and Oil Property on the Formation and Stability of Crude Oil Emulsion. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 979–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.F.; Lim, J.S.; Dol, S.S. Crude oil emulsion: A review on formation, classification and stability of water-in-oil emulsions. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 135, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Li, C.; Yang, S.; Yang, F.; Chen, Y. Experimental Investigation of the Rheological Properties of a Typical Waxy Crude Oil Treated with Supercritical CO2 and the Stability Change in Its Emulsion. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 4731–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Crawshaw, J. Measurement of the Rheology of Crude Oil in Equilibrium with CO2 at Reservoir Conditions. JoVE 2017, 124, e55749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Well No. | Asphaltene (%) | Saturates (%) | Aromatics (%) | Resin (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.39 | 85.01 | 9.22 | 5.38 |

| 2 | 4.67 | 46.99 | 17.20 | 31.14 |

| 3 | 9.08 | 39.31 | 20.94 | 30.68 |

| 4 | 34.88 | 53.01 | 8.99 | 3.11 |

| 5 | 2.83 | 77.57 | 12.49 | 7.10 |

| 6 | 19.08 | 63.92 | 12.25 | 4.74 |

| Sample No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm3) | 0.8531 | 0.8560 | 0.8510 | 0.8549 | 0.8483 | 0.8465 |

| Sample No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| water content. (%) | 73.88 | 59.85 | 11.09 | 58.3 | 16.92 | 13.54 |

| Sample No. | Demulsifier Type | Concentration (mg/L) | Temperature (°C) | Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | HTMAC\TPR-03\RKP-1 | 50/100/110/120 /130/140/150/200 | 35/40/45 /50/55/60 | 20/25/30/35 /40/50/60 |

| Demulsifier Type | Concentration (mg/L) | Temperature (°C) | Time (min) | Demulsification Rate (%) | Water Content (%) | Cleanliness of Aqueous Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RKP-2 | 150 | 50 | 60 | 90.0 | 23.1 | 1 |

| TPR-03 | 150 | 50 | 40 | 100.0 | 0 | 1 |

| HTMAC | 150 | 50 | 60 | 73.3 | 44.4 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiao, M.; Zhang, F.; Li, W. Rheological Properties of Crude Oil and Produced Emulsion from CO2 Flooding. Energies 2025, 18, 739. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18030739

Qiao M, Zhang F, Li W. Rheological Properties of Crude Oil and Produced Emulsion from CO2 Flooding. Energies. 2025; 18(3):739. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18030739

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiao, Mingzheng, Fan Zhang, and Weiqi Li. 2025. "Rheological Properties of Crude Oil and Produced Emulsion from CO2 Flooding" Energies 18, no. 3: 739. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18030739

APA StyleQiao, M., Zhang, F., & Li, W. (2025). Rheological Properties of Crude Oil and Produced Emulsion from CO2 Flooding. Energies, 18(3), 739. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18030739