Abstract

The energy transition requires substantial financial investments and the adoption of innovative technological solutions. The aim of this paper is to analyze the economic and technological aspects of implementing zero-emission strategies as a key component of the transition toward a carbon-neutral economy. The study assesses the costs, benefits, and challenges of these strategies, with a particular focus on wind farms and nuclear power, including small modular reactors (SMRs). The paper presents an in-depth examination of key examples, including onshore and offshore wind farms, as well as nuclear energy from both large-scale and small modular reactors. It highlights their construction and operating costs, associated benefits, and challenges. The investment required to generate 1 MW of energy varies significantly depending on the technology: onshore wind farms range from $1,300,000 to $2,100,000, offshore wind farms from $3,000,000 to $5,500,000, traditional nuclear power plants from $3,000,000 to $5,000,000, while small modular reactors (SMRs) require between $5,000,000 and $10,000,000 per MW. The discussion underscores the critical role of wind farms in diversifying renewable energy sources while addressing the high capital requirements and technical complexities of nuclear power, including both traditional large-scale reactors and emerging SMRs. By evaluating these energy solutions, the article contributes to a broader understanding of the economic and technological challenges essential for advancing a sustainable energy future.

1. Introduction

The pursuit of zero emissions has become a priority for energy companies worldwide, driving them to implement various strategies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions [1]. To achieve reduction plans targeting net-zero emissions by 2050, companies, including energy providers, must adopt and strengthen policies promoting the production of clean energy. However, the transition to a low-emission economy requires substantial financial investments and advanced technological solutions [2]. Companies are adopting different strategies to meet these challenges, including adaptation strategies, prosumer strategies, and strategies for integrating sustainable technologies [3,4].

The study aims to analyze zero-emission strategies adopted by energy companies in their efforts to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, assess their economic impact, assess the impact of national and international regulations, and identify key technological solutions. Depending on geographical location and climatic conditions, the strategies implemented may differ. In regions with low daily and annual solar radiation, investments in photovoltaics may not be an optimal solution, similarly to wind farms in areas with low wind intensity. It is important to locate the wind turbines in windy areas with the appropriate positioning of the blades so that the energy production is most effective [5]. The choice of emission reduction technologies is also influenced by factors such as the availability of natural resources, the structure of the power grid, and local economic and social conditions. In addition, the structure of energy consumption and the level of development of energy infrastructure may determine whether distributed prosumer systems or large, central renewable sources should be the priority.

The adaptation strategy involves adjusting existing infrastructure and production processes to meet new environmental, legal, and social requirements, playing a key role in the transformation of energy companies toward zero emissions. In practice, this means not only modernizing technology but also implementing comprehensive organizational and operational changes that allow companies to meet increasing stakeholder expectations. Legal requirements, such as EU regulations on reducing greenhouse gas emissions and national emission standards, force companies to invest in technologies that reduce their carbon footprint. In the context of the energy crisis, EU regulations on solidarity mechanisms have emerged, which involve cooperation between states and businesses for sharing energy resources and jointly funding clean energy investments. This aims to ensure both energy security and the achievement of climate goals [6].

An example of infrastructure that helps reduce emissions is carbon capture and storage (CCS) systems in power plants, which can significantly lower CO2 emissions. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) systems play a crucial role in the energy transformation process by significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions. These technologies capture CO2 emissions directly from power plants and industrial facilities, preventing them from being released into the atmosphere. Once captured, the CO2 is transported and securely stored underground in geological formations, such as depleted oil and gas fields or deep salt caves. However, the costs associated with such investments are high. According to an IEA report, the implementation of CCS technology is estimated to cost between $50 to $350 per ton of captured CO2, depending on the sector and the concentration of CO2 [7]. In a typical coal-fired power plant, the process of capturing and compressing CO2 can consume around 250 kWh of energy per ton of CO2 captured. Since such a power plant generates approximately 1200 kWh of electricity per ton of CO2 emitted, the CCS process would consume about 20% of the generated energy. This high energy demand reduces the overall efficiency of electricity production. Therefore, it is valuable to consider not only the direct costs of CCS technology but also the additional energy required to capture the CO2, as it can significantly impact the overall energy efficiency and economic feasibility of the system [8]. Batteries used in renewable energy systems storage pose several challenges in terms of utilization and disposal due to their limited lifespan, resource-intensive production, and difficulties with recycling. These issues not only affect the economic viability of energy storage solutions but also present significant environmental concerns. Effective solutions are needed to minimize these impacts and improve sustainability. One approach is the development of second-life applications, where used batteries are repurposed for other energy storage functions, thus, extending their lifespan. Another solution is advancing battery recycling technologies, which can reduce the demand for raw materials and decrease waste.

The prosumer strategy focuses on involving energy consumers in energy production and consumption, such as through the development of photovoltaic micro-installations or energy storage systems for individual customers. Prosumer strategies promote local production of renewable energy, reducing dependence on fossil fuels and increasing energy efficiency. The prosumer strategy empowers individual customers, turning them from passive energy consumers into active participants in the energy market [9]. Through this strategy, consumers can not only use energy provided by traditional suppliers but also produce it themselves, for example, through photovoltaic installations, small wind turbines, or other micro-installations [10]. A prosumer has the ability to meet their own energy needs and sell excess energy back to the grid, making them an equal participant in the market [11]. This type of activity promotes the decentralization of the energy system, increases its flexibility, and contributes to the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, this strategy requires investments in infrastructure, such as smart meters, energy storage systems, and digital platforms for managing energy flow, which generates additional costs but also creates new opportunities for savings and profits for prosumers [12]. This strategy requires modernization investments in infrastructure to integrate decentralized energy sources with the grid, which can cost up to $1–2 million per installed MW [13]. However, companies also benefit from reduced needs for expanding large power plants and lowering energy transmission costs over long distances.

The strategy of integrating sustainable technologies involves building new renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar farms, and developing advanced energy storage technologies. Although investment costs for offshore wind farms or battery energy storage systems are high—ranging from $2.5 to $4 million per MW for wind farms and $300 to $500 per kWh of capacity for battery storage systems—the long-term economic benefits, such as stable energy prices and the elimination of CO2 emission-related costs, make this strategy economically viable.

The economic and technological challenges primarily relate to the need to incur high upfront costs for implementing advanced technologies, integrating networks and providing energy storage to ensure the reliability and continuity of energy supply. The research presented in this paper discusses key economic aspects related to choosing these strategies and technologies that play a decisive role in this transformation. Each of these paths requires not only financial investments but also careful planning to ensure that investments bring both environmental and economic benefits [14].

2. Literature Review

In the ongoing research on the economic and technological challenges of energy companies in the area of zero-emission strategies, the scientific literature offers many valuable studies. International scientific journals publish extensive analyses related to energy transformation, technological innovations and the costs of adapting companies to zero-emission requirements. Articles often focus on the integration of renewable energy sources and solutions that increase energy efficiency, which is a key element of energy companies’ strategies.

Energy economics journals provide in-depth financial and economic analyses, indicating the long-term benefits of investing in clean energy. The literature also includes interdisciplinary studies that combine environmental, technological, and social aspects. These diverse sources provide energy companies with comprehensive knowledge necessary to develop and implement effective zero-emission transformation strategies.

The results of the literature review related to the discussed topic have been summarized and presented in Table 1, which allows for a synthetic comparison of key conclusions and the most important sources.

Table 1.

Selected scientific articles discussing issues related to the transformation towards zero emissions.

The materials presented in Table 1 also highlight the significant role of strategies related to green energy, which can be further explored through the different approaches. According to Sulich and Grudziński [24], energy companies adopt three primary strategies to achieve green energy: isolation, market response, and adaptation. These strategies reflect the approaches firms take to align with environmental goals, market demands, and regulatory requirements in the transition to sustainable energy sources. It is also valuable to discuss and analyze these strategies in the context of the data presented, as they provide insight into the broader landscape of green energy adoption. The first is the isolation strategy, in which the company avoids or minimizes the impact of external factors, focusing on internal development. The next strategy is the market response strategy, where companies respond to the growing demand for renewable energy and to pressure from consumers and market regulations. Finally, the third strategy is the adaptation strategy, which includes active adjustment to changing market and environmental conditions by implementing new technologies and innovative solutions that enable the efficient use of green energy. Similarly, Borowski [4] distinguishes two approaches within the adaptation strategy: passive adaptation and active adaptation. Passive adaptation involves adapting to changes in a passive manner, reacting to them as they occur, often by implementing regulatory requirements without major changes in previous practices. Active adaptation, on the other hand, means a proactive approach, where companies initiate changes themselves, investing in modern technologies, developing innovative solutions and implementing strategies that anticipate market and regulatory requirements, focusing on sustainable development and striving for zero emissions. Both concepts, those of Sulich and Grudziński, as well as Borowski, point to the key role of adaptation and flexibility in making strategic decisions by energy companies, which must face the growing requirements for green energy and the constant development of technology and regulations.

The papers presented in Table 1 demonstrate that achieving sustainable goals requires significant efforts to develop the renewable energy sector and ensure the provision of affordable, clean, and reliable energy. This can be achieved by investing in renewable technologies and supporting policies for the green transition. However, despite these goals, fossil fuels remain crucial in the EU energy balance due to their availability, price stability and infrastructure. Therefore, decarbonization measures must be implemented in conjunction with a gradual transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy, taking into account the specific needs and possibilities of each country.

3. Materials and Methods

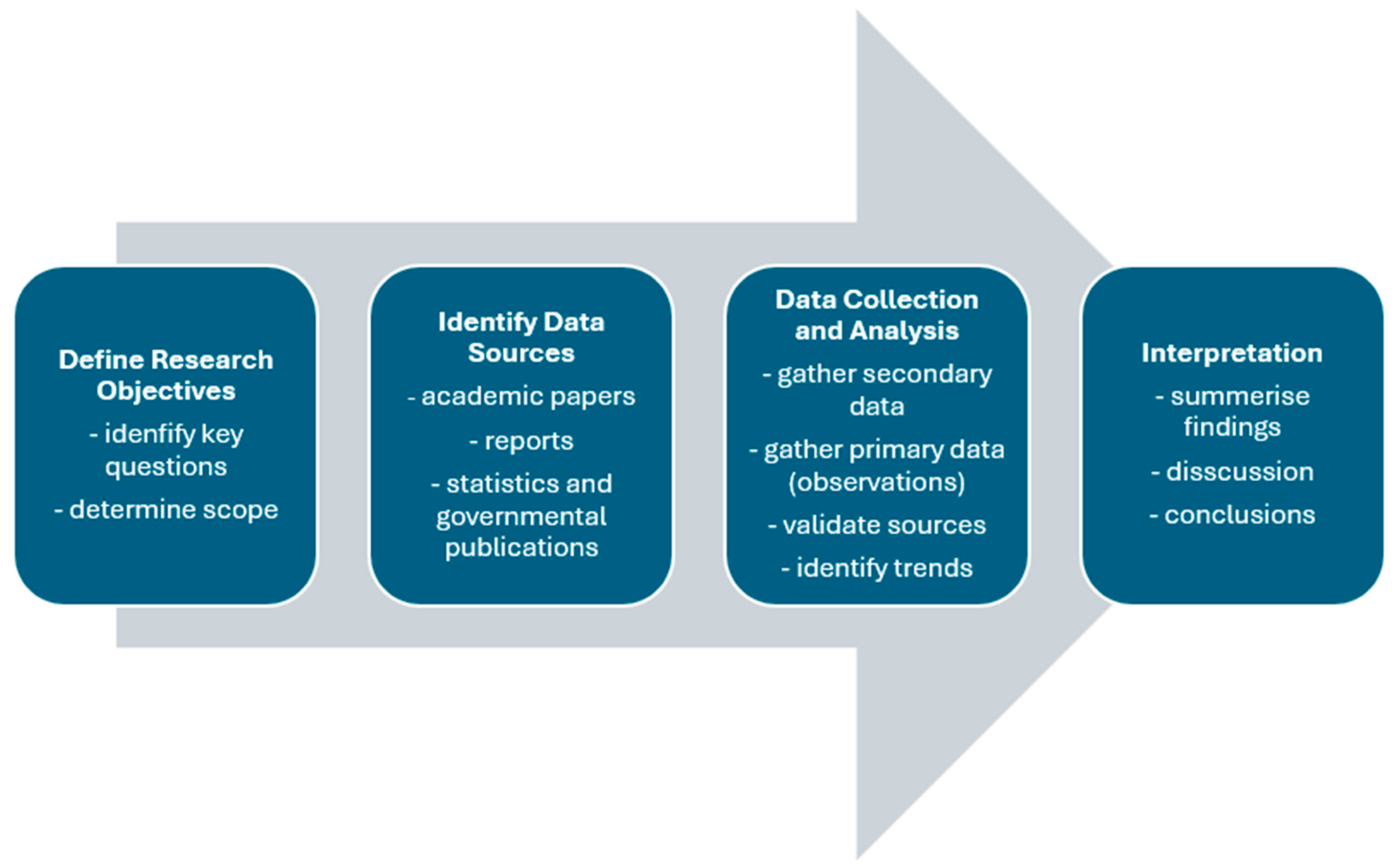

The research methods applied in the study aimed at providing a comprehensive analysis of investments in renewable energy sources, particularly in the context of actions taken by energy companies and prosumers. The research was based on two main approaches: primary and secondary research, which together allowed for a complete understanding of the phenomenon under discussion. Figure 1 shows the concept of the desk research method, outlining the key steps involved in its application. These steps include defining and identifying scientific resources, as well as collecting, analyzing, and interpreting existing data to derive meaningful and valuable insights.

Figure 1.

Stages of desk research implementation.

Primary research involved direct observations regarding investments in renewable energy sources, with a focus on photovoltaic and wind farms, as well as PV installations and wind turbines used by prosumers. Data were collected on the current status of these investments, including their size, efficiency, initial costs, and long-term results. The observations were conducted in various locations, enabling a comparison of the effectiveness of solutions under different conditions. The use of primary research methods allowed for the collection of reliable and detailed data that directly addressed the research questions concerning the implementation of renewable energy sources in the context of the energy sector and prosumer activities.

Secondary research involved the analysis of available materials and information sources, such as industry reports, statistical data, and scientific articles from prestigious international journals, which are recognized for their rigorous peer-review process and high academic standards. In particular, reports published by the International Energy Agency (IEA), the European Environment Agency (EEA), as well as national reports prepared by the Polish Renewable Energy Association (PSEW) and Polish Power Grid (PSE), were utilized. Statistical data were sourced from databases such as Eurostat, the Central Statistical Office (GUS), and REN21′s Renewable Global Status Report. Based on secondary research, it was possible to determine the costs associated with investments in renewable energy sources.

Secondary research relied on reputable publications recognized by the academic community to ensure that the analysis was based on reliable and credible sources. Additionally, numerous scientific articles published in leading international journals such as Energies, Renewable Energy, Energy Policy, Sustainability, as well as Journal of Cleaner Production were analyzed. These articles provided valuable insights into the theoretical and practical aspects of implementing renewable energy sources, including detailed financial analyses, environmental impacts, and strategies applied in different regions of the world. The recognition of these journals in the academic community, along with their high citation rates, confirms that the content they contain provides a solid foundation for formulating conclusions and conducting further research. Such a selection of sources helped establish strong theoretical and practical foundations for studying phenomena related to investments in renewable energy sources, further enhancing the credibility and substantive value of the analyses.

The materials used provided detailed information on current market trends, policies supporting the development of renewable energy sources, statistics on renewable energy production and consumption, as well as forecasts for sector growth. This enabled the comparison of primary research findings with a broad range of publicly available data, enriching the analysis with both global and national perspectives and allowing for the identification of key challenges and opportunities in this area. Analyzing these materials, including renowned scientific publications, also facilitated the verification of the results obtained from the primary research and provided solid theoretical foundations for drawing conclusions regarding the directions of investment in renewable energy sources.

The combination of both research methods allowed for a more comprehensive picture of the development of the renewable energy market and enabled more precise conclusions about the future of this sector, both in the context of large energy companies and individual investors—prosumers [25].

4. Results and Discussion

The pursuit of zero emissions presents not only technological challenges for energy companies but also organizational and structural ones. To implement ambitious emission reduction plans aimed at achieving net zero emissions by 2050, companies—particularly in the energy sector—must not only adopt policies promoting clean energy production but also make significant financial investments and adopt advanced technologies. Estimates of the global costs to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 range from around $3.5 trillion to as much as $9 trillion per year. The figures given above vary depending on estimates published in different reports (e.g., Energy Transitions Commission, McKinsey & Company, International Energy Agency (IEA)) [26,27,28]. These figures underline the significant financial commitment required for a global low-carbon transition.

A crucial aspect of this process is the development of long-term strategies that facilitate a smooth transition to renewable energy-based production while minimizing financial risks. Special emphasis should be placed on creating synergies between environmental and economic goals, which requires integrating sustainable technologies and fostering collaboration with diverse stakeholders, including prosumers and financial institutions.

Flexibility in implementing these strategies is essential, enabling companies to adapt to rapidly changing market, regulatory, and technological conditions. To address climate, environmental, and societal challenges, companies are adopting various approaches. These include adaptation strategies, which focus on aligning operations with external environmental, regulatory, and market requirements; prosumer strategies, which emphasize partnerships with consumers who produce energy for their own use and actively influence the energy sector; and sustainable technology integration strategies, which prioritize implementing modern technological solutions to enhance energy efficiency and reduce emissions.

Each of these strategies requires an appropriate financing model that ensures efficient resource utilization while achieving both environmental and business objectives. Analyzing financing mechanisms and available sources of capital is critical for understanding how companies can effectively pursue their energy transformation goals.

4.1. The Economic Aspect of Energy Transformation

The costs of investing in low-emission energy are significantly higher than those associated with fossil fuels. It is estimated that for every dollar spent on fossil fuels, an average of three dollars is invested in low-emission technologies. The total cost of fully decarbonizing the global energy system by 2050 could amount to $215 trillion, representing a 19% increase compared to a transition that does not account for climate goals. These estimates are based on analyses conducted by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) [29,30] and the International Energy Agency (IEA) [31,32].

Despite these high costs, the necessity of reducing greenhouse gas emissions compels action to finance various investments aimed at achieving net-zero emissions [33]. These investments include renewable energy sources (RES), such as wind farms, photovoltaic installations, and green hydrogen production [34,35], as well as technologies enabling the production of clean energy from coal, such as advanced carbon capture and storage (CCS) systems and low-emission coal-fired boilers [36,37]. These latter solutions can serve as critical transitional elements in energy transformation, particularly in regions heavily dependent on fossil fuels.

Investments in low-emission energy also yield measurable economic benefits. Long-term savings stem from reduced fuel expenditures, lower healthcare costs associated with environmental pollution [38], and the avoidance of potential carbon emission penalties. Increased investment in environmentally and socially friendly energy development delivers multidimensional benefits, not only in the context of climate protection but also in improving quality of life and reducing public health expenditures. Energy companies can reduce social inequality during the transition to renewable energy systems by offering financial support programs, equitable access to energy, and targeted investments in communities that are energy poverty. Collaborative efforts with local governments and NGOs can also help create inclusive policies and infrastructure to promote energy affordability and resilience.

Fossil fuel-based energy production generates significant amounts of air pollutants, such as particulate matter (PM2.5, PM10), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and nitrogen oxides (NOx). These pollutants are direct causes of numerous respiratory, cardiovascular, and cancer-related illnesses [39]. According to studies by the World Health Organization (WHO), air pollution is one of the leading health risk factors, causing millions of premature deaths annually worldwide [40,41]. By replacing fossil fuels with clean energy sources, the overall air quality improves, leading to fewer illnesses and lower healthcare costs.

Investments in renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, and geothermal energy, significantly reduce emissions of these harmful substances, leading to improved air quality. As a result, direct healthcare costs for treating pollution-related diseases decrease, as do indirect costs related to lost worker productivity, sick leave, and long-term health consequences [42].

From an economic perspective, initial increased spending on clean energy pays off over the long term through significant reductions in costs associated with maintaining societal well-being. Numerous economic models indicate that reduced healthcare expenses and improved economic productivity resulting from better environmental quality can yield benefits far exceeding the initial investment [43,44]. Consequently, the development of environmentally friendly energy should be viewed not as an expense but as a strategic investment in public health, social stability, and long-term economic sustainability.

Economically, this phenomenon of incurring additional upfront costs to achieve long-term savings is often referred to as “initial costs for long-term benefits” or the “costs and benefits shift” [45]. It is also frequently linked to the concept of “sustainable investment”, which involves expenditures aimed at long-term improvements in public health, environmental protection, and quality of life in the context of sustainable development [46].

In a broader context, this phenomenon is also associated with the theory of “hidden costs” or “externalities”, where the costs of negative environmental and health impacts are often overlooked in traditional cost–benefit analyses. Within the framework of sustainable investments, these “hidden costs” are accounted for, and investments in clean energy or improved energy efficiency become long-term solutions for reducing expenses related to diseases, pollution, and environmental degradation [47].

In economic terms, a related concept is “ecological capital”, referring to the value of natural and ecological resources that must be preserved or invested in to reduce long-term external costs [48]. In public health, the term “preventive cost-effectiveness” emphasizes the benefits of early investments in preventing health or environmental issues before they become more expensive to address [49].

In short, this can be considered “strategic investments in long-term prevention” in the context of sustainable development and minimizing external costs, leading to a better balance of costs and benefits over the long term.

Energy transformation supports the creation of healthier and more sustainable communities. It encompasses not only the development of renewable energy technologies but also comprehensive adaptation of energy companies to new challenges. These companies must transform their business models, invest in infrastructure modernization, and develop employee competencies in environmentally friendly technologies [3,50].

This process can also help reduce social inequalities by creating new jobs in the green energy sector and in companies integrating renewable energy sources with existing systems [51]. Adapting energy companies also means improving energy access in developing regions through investments in local solutions, such as micro solar installations or small wind farms, which not only meet energy needs but also support local economic development.

Moreover, by adapting to the new reality, energy companies can implement solutions that minimize health burdens on the poorest social groups, who are most vulnerable to the adverse effects of environmental pollution. For example, phasing out coal-fired power plants and replacing them with renewable sources can significantly reduce air pollution, providing direct health benefits to local communities [52].

Energy transformation is, therefore, not just a technological change but also a strategic adjustment by enterprises, enabling the achievement of sustainable development goals and the construction of a more equitable energy system [53]. Additionally, the development of new economic sectors, such as green hydrogen production, wind farm construction, and CO2 capture and storage infrastructure, creates thousands of new jobs and stimulates technological innovation. These benefits demonstrate that financing energy transformation not only supports climate goals but also serves as a catalyst for sustainable economic development [54].

4.2. Technologies Supporting Zero Emissions

Achieving zero-emission goals requires investment in advanced technologies that will allow replacing traditional energy sources with more ecological solutions [55]. Renewable energy sources, such as wind, solar, geothermal energy and energy storage technologies, which enable stabilization of supply even in conditions of variable production, play a key role here. The development of lithium-ion batteries, flow batteries and other innovative solutions in the field of energy storage is the foundation for the efficient use of renewable energy [56].

Another important element of zero-emission technologies is the development of supporting infrastructure, such as smart energy networks, which allow for more efficient management of energy flows, minimizing losses and optimizing its consumption. Another important aspect is technologies related to carbon capture, storage, and utilization (CCUS), which allow for reduced emissions from heavy industry and fossil fuel-based power plants [57].

In addition, transport plays a significant role in achieving emission neutrality. The introduction of electric vehicles and the development of infrastructure for charging them, as well as research into the use of hydrogen as the fuel of the future, are key directions of transformation in this sector. Hydrogen, especially when produced using green energy, has the potential to replace fossil fuels in trucking, shipping, and aviation. The economic implications of transitioning industrial facilities to green hydrogen fuel include high initial costs for production, infrastructure, and technology integration. Green hydrogen, produced via electrolysis using renewable energy, is currently the most expensive type of hydrogen. In comparison, gray hydrogen, produced from natural gas, is cheaper but emits significant CO2. However, green hydrogen offers long-term savings through lower operational costs, especially as renewable energy becomes more affordable, and plays a crucial role in reducing emissions in hard-to-abate sectors like steel and chemical production, where decarbonization is particularly challenging.

Advanced digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, data analytics and the Internet of Things (IoT) can support the achievement of zero-emission goals by improving process efficiency, better monitoring energy consumption and optimizing energy systems. Digitalization also enables better forecasting of energy demand and identification of areas requiring modernization [58,59]. Digital technologies like AI and IoT contribute to optimizing energy systems for zero-emission goals by improving efficiency through real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance, and optimizing energy distribution and usage. AI can analyze large datasets to predict demand fluctuations, while IoT devices enable better integration of renewable sources, enhancing grid flexibility. These technologies also support the management of energy storage systems, ensuring a consistent supply even with intermittent renewable energy sources.

Investments in green technologies not only contribute to reducing emissions, but also stimulate the development of new economic sectors, create jobs and support the development of an innovation-based economy. In this way, advanced technologies become not only a tool to combat the climate crisis but also a foundation for future sustainable development. Table 2 presents the key technologies and infrastructures supporting this transformation.

Table 2.

Technological solution toward zero-emission.

The descriptions presented in Table 2 indicate that the implementation of modern technologies that support emission reduction and environmental protection includes various approaches that together create a comprehensive system of actions for sustainable development. Investments in renewable energy sources, such as onshore and offshore wind farms, photovoltaics, and hydropower, are of key importance, which allow for a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and the stabilization of energy systems. The modernization of gas power plants by implementing CCS technology and the transition to green hydrogen enable a more ecological use of existing infrastructure [63].

Energy storage, including the development of advanced batteries, is crucial for the stability of the energy system based on renewable sources, which are characterized by production variability. Hydropower additionally supports the balancing of the system, enabling efficient storage of energy in the form of water pumped to a higher level.

At the same time, the implementation of technologies requires solving the challenges related to them, such as the impact on the environment or the high cost of initial investments, which should be included in energy transformation strategies. The joint action of these solutions creates a solid foundation for achieving climate goals and environmental protection in a global perspective.

Companies investing in zero-emission technologies play a key role in the global energy transformation. Although the costs associated with decarbonization are high, the ecological, economic, and social benefits outweigh the potential financial burden. However, achieving climate goals requires international cooperation, political support, and the involvement of the private sector in the development and implementation of innovative technologies [64]. Only integrated actions will allow us to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. International cooperation fosters knowledge sharing, resource pooling, and coordinated policies in global forums such as COPs that drive clean energy adoption. By adopting common actions and coordinating them, countries can accelerate innovation, reduce costs, and implement sustainable solutions more effectively, ensuring a faster transformation towards a low-carbon future.

4.3. Economic Aspects of Building Wind Farms and Nuclear Power Plants

In this economic research section of the paper, a detailed comparison of the costs associated with different energy technologies will be presented. This will include examining the costs associated with building wind farms, both onshore and offshore, as well as the costs of building large nuclear power plants and small modular reactors (SMRs). By breaking down these costs, a clearer understanding of the economic feasibility of each technology and their potential contribution to a sustainable energy mix will be provided. The comparison will also highlight differences in scalability, operational efficiency, and the long-term financial implications of investing in each of these energy sources.

4.3.1. The Costs of Building Onshore and Offshore Wind Farms

The construction of wind farms, both onshore and offshore, plays a key role in the energy transformation and increases the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix. However, both types of installations differ significantly in terms of costs related to implementation, maintenance and the technology used, which has a direct impact on their economic profitability and the pace of implementation. Onshore wind farms are characterized by relatively lower investment costs, which results from easier access to construction sites, lower technical requirements, and lower costs of transporting components. Additionally, their operation and maintenance are also cheaper compared to offshore installations. However, restrictions related to the availability of suitable locations and often lower wind speeds can affect efficiency and energy production [65]. Offshore wind farms, despite higher construction costs, offer greater possibilities in terms of energy generation thanks to stronger and more stable winds in the open sea. These costs result from the need to build more advanced foundations, specialist installation vessels, and the expansion of the transmission infrastructure that must transport energy to the mainland. In addition, operating offshore wind farms is more expensive due to the harsher environmental conditions that result in more frequent maintenance and more expensive repairs [66].

Despite these differences, both onshore and offshore wind farms contribute to the decarbonization of energy systems. However, their economic viability depends on factors such as support policies, access to cheap financing, technological development, and local geographical and climatic conditions. The key challenge remains to optimize the costs and improve the efficiency of both types of installations so that they can play an even greater role in the global energy transformation. Table 3 and Table 4 provide a detailed analysis of the costs associated with the construction of wind farms [67].

Table 3.

Costs per 1 MW generated energy related to the construction of onshore wind farms.

Table 4.

Costs of Building Offshore Wind Farms per 1 MW generated energy.

From Table 3, it can be observed that the total cost of building 1 MW of an onshore wind farm ranges between 1,300,000 and 2,100,000 USD, influenced by factors such as location, turbine size, and logistical complexities. These costs encompass various components, including the purchase of turbines, construction, grid connection, land acquisition, and operational infrastructure. Although onshore wind farms generally require lower initial investments compared to offshore alternatives, the cost variability is significant, driven by terrain characteristics, permitting processes, and regional market conditions. Over time, continuous advancements in turbine technology and the achievement of economies of scale are expected to drive these costs down further, enhancing the feasibility and attractiveness of onshore wind as a leading source of clean energy.

From Table 4, it can be observed that the total cost of building 1 MW of an off-shore wind farm ranges from approximately 3,000,000 to 5,500,000 USD, significantly higher than onshore wind farms. These costs include specialized turbines, foundation structures, grid connections, and increased logistical challenges due to marine conditions. Despite higher initial investments, offshore wind farms benefit from stronger, more consistent winds, leading to greater energy output and efficiency over time.

The costs and considerations associated with wind farm development are influenced by a range of factors, including geographic location, seabed characteristics, the distance to grid connections, and prevailing market dynamics. Offshore wind farms, situated in marine environments, face unique challenges such as higher construction costs, more complex logistics, and greater exposure to harsh weather conditions. Onshore wind farms, while typically more cost-effective, may contend with land-use conflicts, variable wind conditions, and local regulatory requirements. These differences underscore the nuanced trade-offs involved in selecting between onshore and offshore wind energy solutions. Table 5 provides a detailed comparison of the most significant elements that distinguish onshore and offshore wind farms.

Table 5.

Comparison between onshore and offshore installations.

Table 5 clearly illustrates the differences between onshore and offshore wind farms in terms of cost and operational complexity. Offshore wind farms, although significantly more expensive to build due to the complex requirements of marine environments, offer the advantage of utilizing stronger and more stable wind resources. Onshore wind farms, on the other hand, are a more cost-effective and logistically straightforward option, but they are often hampered by challenges such as land-use conflicts and inconsistent wind conditions. These differences highlight the trade-offs between the two approaches, emphasizing the critical role of tailored site planning and technological innovation in promoting sustainable energy solutions. Ultimately, this comparison highlights the clear balance between cost-efficiency, scalability, and environmental impact that defines any type of wind energy project.

4.3.2. The Costs of Building Large-Scale Nuclear Power Plants and Small Modular Reactors

Nuclear power plays a key role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions by offering a stable and reliable source of energy that does not emit carbon dioxide during operation. Nuclear energy can be produced in two main types of reactors: large-scale nuclear reactors and small modular reactors (SMRs). Both solutions have their unique advantages and disadvantages, which concern both technical and economic aspects [73].

Large-scale reactors are capable of producing large amounts of energy, which makes them effective in meeting energy demands on an industrial scale. However, the construction of such units is associated with high capital costs and long lead times, which makes them less flexible in response to changing energy needs. In addition, due to their size, they require extensive infrastructure and access to large areas.

Small modular reactors (SMRs) are a modern solution that offers greater flexibility due to the possibility of building in modules, which allows for a gradual increase in production capacity. SMR construction costs are usually lower per unit project, and their design allows for location in places inaccessible to large reactors. The disadvantage, however, is their lower efficiency on a global scale and the still developing technology market, which can affect availability and operating costs [74].

Key factors related to the choice between these solutions, such as construction costs, implementation time, efficiency, or location possibilities, are presented in the table below, which allows for a comprehensive comparison of both technologies. This allows for a better understanding of their potential and limitations in the context of the global energy transformation and the fight against greenhouse gas emissions. The basic differences between these two types of energy production are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Main differences between large scale and small modular reactors.

Table 6 highlights the efficiency and low-emission benefits of nuclear reactors, both traditional large-scale designs and small modular reactors (SMRs), while underscoring the significant differences in their construction and operational characteristics.

The disparity in construction timelines between these two reactor types arises from differences in scale, complexity, and construction methodologies. Traditional nuclear reactors are large-scale projects requiring extensive on-site construction, advanced systems, and lengthy regulatory and licensing processes. The on-site nature of their construction increases logistical challenges and the potential for delays caused by weather, supply chain disruptions, or unforeseen issues.

In contrast, SMRs leverage modular and standardized designs, enabling the majority of components to be prefabricated in controlled factory environments. This approach reduces on-site construction efforts, accelerates assembly, and minimizes delays. SMRs also benefit from simplified regulatory requirements in some regions due to their smaller size and inherent safety features. Their incremental deployment and reduced infrastructure demands further shorten construction timelines, making them well-suited for locations with limited resources or variable energy needs [77].

Large-scale reactors are characterized by high initial costs, long lead times, and economic efficiency primarily in large industrial applications. SMRs, while having higher per-unit energy operating costs, offer shorter construction timelines, lower upfront investments, and greater flexibility in site selection. This flexibility allows SMRs to be tailored to specific local conditions, making them an appealing solution for areas with limited infrastructure or fluctuating energy demands.

Both reactor types play a vital role in the transition to sustainable energy. The decision between them should consider local economic, technical, and environmental conditions to optimize their integration into energy systems.

The importance of the renewable energy sector in mitigating climate change has been in the spotlight for years, constituting a key element of the greenhouse gas emission reduction strategy. However, it is equally important to take into account climate threats that can affect the stability and efficiency of renewable energy systems. Extreme weather events, variability of atmospheric conditions, or limited availability of raw materials can pose challenges for the sector. Therefore, it is necessary for energy companies to adapt by implementing modern technologies and investing in infrastructures resistant to climate change and flexible management models that will allow for long-term energy transformation goals to be achieved [78].

5. Recommendation

Based on the conducted research, key recommendations can be formulated regarding the development of renewable energy, taking into account various technologies and the specifics of location, region, and climate. In addition, optimizing project locations, modernizing infrastructure, and integrating digital technologies such as AI and IoT in the energy sector further improve operational efficiency and cost effectiveness. Economic and technological analysis serves as the foundation for these recommendations, helping to identify the most effective strategies and technologies that can be implemented in different parts of the world, considering specific geographical and infrastructural conditions.

1. Onshore Wind Farms

Economic Analysis—The construction of onshore wind farms involves investment costs that include the purchase of turbines, the construction of transmission infrastructure, and the modernization of local energy networks. The cost of installing wind turbines varies depending on the region, but the average construction cost is approximately $1.3–2.1 million per MW of capacity. On the other hand, operational costs for wind farms are relatively low, as the energy source (wind) is free.

Technological Analysis—Modern wind turbine technologies offer high efficiency and increased durability (the lifespan of wind turbines is usually around 25–30 years). However, wind quality and land availability can be limiting factors in some regions.

2. Offshore Wind Farms

Economic Analysis—The construction of offshore wind farms comes with higher investment costs compared to onshore farms. The installation cost of offshore farms ranges from $3 to $5.5 million per MW of capacity. Additionally, the need to build subsea transmission infrastructure and adapt systems to challenging marine conditions increases costs. Nevertheless, in the long term, offshore wind farms can offer higher generation capacities and greater efficiency due to stronger and more stable winds.

Technological Analysis—Offshore technologies are more advanced but require specialized skills in the installation and maintenance of turbines in difficult maritime conditions. The increase in the efficiency of offshore turbines, particularly in terms of their unit power, makes investments in offshore wind farms increasingly cost-effective.

3. Large-Scale Nuclear Energy

Economic Analysis—Nuclear energy requires high initial investment costs, with the cost of constructing large nuclear power plants ranging from $6 to $9 billion per reactor. However, once construction is completed, nuclear plants offer a stable and high-capacity energy source, which is beneficial in countries with high energy demand. Operating costs are relatively low, but long-term costs associated with safety and radioactive waste management are significant. The investment cost for nuclear energy projects has been calculated, estimating that 1 MW ranges between $3 to $5 million USD, depending on the region and reactor type.

Technological Analysis—Modern nuclear reactor technologies offer higher efficiency and safety, but technological challenges, such as waste management and safety concerns, present substantial limitations. Additionally, the long construction period for large nuclear plants makes it difficult to respond quickly to changing energy needs.

4. Small Modular Reactors (SMR)

Economic Analysis—Small modular reactors (SMRs) offer lower initial costs, estimated at $1–3 billion per reactor, making them more accessible to developing countries and regions with lower energy demand. SMRs can be more flexible and faster to construct, which is a significant advantage. The investment required for 1 MW of SMR capacity is typically between $3 to $5 million, depending on the type and location. SMRs can be more flexible and faster to construct, which is a significant advantage.

Technological Analysis—SMRs are a technology that offers greater safety and flexibility, especially in smaller locations. Their modular design allows for faster installation and adaptation to specific local conditions, which can be a significant advantage in regions with challenging infrastructure conditions.

Based on the conducted analyses, it is recommended to adjust strategies to the specific local geographic and climatic conditions to achieve optimal development of renewable energy. It is also essential to conduct detailed economic and technological analyses that will help select the most appropriate solutions for each region. Ultimately, implementing diverse technologies that consider specific needs and resources will contribute to an effective energy transition, supporting sustainable development goals.

6. Conclusions

The pursuit of carbon neutrality is one of the most significant challenges faced by modern energy companies. Key difficulties encompass both economic and technological aspects tied to transforming the energy sector. Implementing renewable energy solutions, such as onshore and offshore wind farms, nuclear energy, and energy storage, requires substantial financial investment and overcoming numerous technological barriers. The research results indicate that the costs associated with implementation vary depending on the strategy being adopted (e.g., wind or nuclear energy investment strategy). The costs also differ based on the type of renewable energy source.

Investment costs are among the most critical factors companies must consider when planning new projects. Examples presented in research highlight the high expenses associated with energy transformation. Building onshore wind farms is relatively less expensive, costing approximately $1.3–$2.1 million per MW, compared to offshore wind farms, which range from $3 to $5.5 million per MW. Offshore farms, however, are more energy efficient due to stronger and more stable winds but pose additional challenges related to infrastructure, such as undersea cables and transport systems.

Nuclear energy also plays a vital role in the transition to zero emissions, offering a stable energy source with minimal greenhouse gas emissions. Traditional nuclear power plants require massive financial outlays, ranging from $25 billion to $35 billion, and their construction takes 7 to 15 years. In contrast, small modular reactors (SMRs), although more expensive per MW ($5.2–$10.35 million), provide shorter construction times (3–5 years) and greater flexibility in integrating with local energy systems. However, SMRs are still in the early stages of development, facing technological limitations and requiring further investments in research and development.

Another crucial challenge is ensuring the stability of energy networks with the growing share of renewables, which are characterized by variable production. In this context, energy storage, particularly advanced battery systems, becomes an essential component of zero-emission strategies. However, battery costs remain high, and their longevity and efficiency demand further technological improvements.

The transition from fossil fuels to green energy also involves significant social and regulatory hurdles. Acquiring permits, integrating new technologies with existing infrastructure, and gaining public acceptance for new projects require strategic planning and collaboration with governmental and international institutions.

Shifting from fossil fuels to green energy is fraught with obstacles. Retrofitting existing energy systems, managing intermittent renewable energy production, and addressing the high costs of emerging technologies require innovative approaches and substantial capital. Additionally, balancing short-term economic pressures with long-term sustainability goals remains a delicate issue for energy companies navigating the complex landscape of carbon-neutral strategies. The adoption of the chosen strategy also carries environmental consequences. Wind farms, for example, can impact the landscape, alter local ecosystems, and contribute to higher noise levels. On the other hand, nuclear energy, while providing a low-carbon energy source, may involve risks related to accidents or catastrophic events, such as radiation leaks or the long-term management of nuclear waste. These potential environmental impacts must be carefully considered alongside economic and technical factors when making strategic decisions in the energy sector. Additionally, the public perception and acceptance of these technologies can also influence their implementation and success.

In summary, achieving zero emissions requires a balanced approach to economic management, technological innovation, and adaptation to dynamic market and regulatory conditions. Hidden costs, such as environmental impacts and system upgrades, can affect the perceived affordability of energy transformation projects. During the transition to green energy, it is also important to remember that hidden costs, such as environmental impacts and system upgrades, can affect the perceived affordability of energy transition projects. Only through coordinated efforts can energy companies overcome these challenges and drive a sustainable transformation of the global energy system.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the paper are publicly available according to the given citations.

Acknowledgments

I extend my heartfelt gratitude to Nicolaus Copernicus Superior School, Warsaw, Poland (Szkoła Główna Mikołaja Kopernika), and Khazar University, Baku, Azerbaijan, for their support and the collaborative environment that made it possible to conduct the research presented in this paper. The institutions’ commitment to academic excellence and research innovation has been invaluable to the success of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bie, F.; Sun, M.; Wei, X.; Ahmad, M. Transitioning to a zero-emission energy system towards environmental sustainability. Gondwana Res. 2024, 127, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, P.F.; Bandala, E.R.; Lubańska, A.; Stein, E. The Effects and Challenges of Climate Change on the Food-Energy-Water Nexus-Poland as a Case Study. In Optimization in the Agri-Food Supply Chain: Recent Studies; Koubaa, M., Ammar, M.H., Dhouib, D., Mnejja, S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sułek, A.; Borowski, P.F. Business Models on the Energy Market in the Era of a Low-Emission Economy. Energies 2024, 17, 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, P.F. Adaptation strategy on regulated markets of power companies in Poland. Energy Environ. 2019, 30, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Lee, S.M.; Jang, C.M. Techno-economic assessment of wind energy potential at three locations in South Korea using long-term measured wind data. Energies 2017, 10, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhta, K.; Reins, L. Solidarity in European union law and its application in the energy sector. Int. Comp. Law Q. 2023, 72, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/is-carbon-capture-too-expensive (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Share Your Green Design. Available online: https://www.shareyourgreendesign.com/energy-fundamentals-of-carbon-capture/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Parra-Dominguez, J.; Sanchez, E.; Ordonez, A. The prosumer: A systematic review of the new paradigm in energy and sustainable development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulos, N.; Plakas, K.; Birbas, A.; Papalexopoulos, A. Design of a prosumer-centric local energy market: An approach based on prospect theory. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 32014–32032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Vilches, R.; Martín-Martínez, F.; Sánchez-Miralles, Á.; de la Cámara, J.R.G.; Delgado, S.M. Methodology to assess prosumer participation in European electricity markets. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdzik, B.; Jaciow, M.; Wolniak, R.; Wolny, R.; Grebski, W.W. Energy Behaviors of Prosumers in Example of Polish Households. Energies 2023, 16, 3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://epsa.org/understanding-the-costs-of-integrating-energy-resources-in-pjm-analyzing-full-cycle-levelized-costs-of-electricity/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/506756/weighted-average-installed-cost-for-offshore-wind-power-worldwide/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Gaeta, M.; Nsangwe Businge, C.; Gelmini, A. Achieving net zero emissions in Italy by 2050: Challenges and opportunities. Energies 2021, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćetković, J.; Lakić, S.; Živković, A.; Žarković, M.; Vujadinović, R. Economic analysis of measures for GHG emission reduction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadis, E.; Tsatsaronis, G. Challenges in the decarbonization of the energy sector. Energy 2020, 205, 118025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Hao, Y. Economic effects of sustainable energy technology progress under carbon reduction targets: An analysis based on a dynamic multi-regional CGE model. Appl. Energy 2024, 363, 123071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, C.; Song, C.; Meng, D.; Xu, M.; Liu, R.; Liu, Z. The impact of regional policy implementation on the decoupling of carbon emissions and economic development. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 355, 120472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alola, A.A.; Rahko, J. The effects of environmental innovations and international technology spillovers on industrial and energy sector emissions–Evidence from small open economies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 198, 123024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, X. Towards a low-carbon and beautiful world: Assessing the impact of digital technology on the common benefits of pollution reduction and carbon reduction. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.; Zhang, A. Digital finance, regional innovation environment and renewable energy technology innovation: Threshold effects. Renew. Energy 2024, 223, 120036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, P.; Behera, B.; Sethi, N. Assessing the Impact of Fiscal Decentralization and Green Technology Innovation on Renewable Energy Use in European Union Countries: What is the Moderating Role of Political Risks? Renew. Energy 2024, 229, 120715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulich, A.; Grudziński, A. The analysis of strategy types of the renewable energy sector. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2019, 67, 1643–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walliman, N. Research Methods: The Basics, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Net Zero by 2050—Analysis. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Making Mission Possible: Delivering a Net-Zero Economy. Available online: https://www.energy-transitions.org/publications/making-mission-possible/ (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- The Net Zero Transition: What It Would Cost, What It Could Bring. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/be/inspiring-belgium/webinar/the-net-zero-transition-what-it-would-cost-what-it-could-bring (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2024/Nov/IRENA_World_energy_transitions_outlook_2024.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Available online: https://www.irena.org/Publications/2024/Sep/Renewable-Power-Generation-Costs-in-2023 (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022/an-updated-roadmap-to-net-zero-emissions-by-2050 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024?language=en (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Osman, A.I.; Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Msigwa, G.; Farghali, M.; Fawzy, S.; Yap, P.S. Cost, environmental impact, and resilience of renewable energy under a changing climate: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 741–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, P.F. Innovative solutions for the future development of the energy sector. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2024, 27, 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kovač, A.; Paranos, M.; Marciuš, D. Hydrogen in energy transition: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 10016–10035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.C. Breakthrough and innovative clean and efficient coal conversion technology from a chemical engineering perspective. Chem. Eng. Sci. X 2021, 10, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramošljika, B.; Blecich, P.; Bonefačić, I.; Glažar, V. Advanced ultra-supercritical coal-fired power plant with post-combustion carbon capture: Analysis of electricity penalty and CO2 emission reduction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughlin, D.H.; Barron, A.R.; Chettri, C.B.; O’Meara, A.; Sarmiento, L.; Dong, D.; Kaplan, P.O. Health and air pollutant emission impacts of net zero CO2 by 2050 scenarios from the energy modeling forum 37 study. Energy Clim. Change 2024, 5, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zah, S.C.; Ogwu, M.C.; Etim, N.G.; Shahsavani, A.; Namvar, Z. Short-Term Health Effects of Air Pollution. In Air Pollutants in the Context of One Health; The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Izah, S.C., Ogwu, M.C., Shahsavani, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health Aspects of Air Pollution: Results from the WHO Project “Systematic Review of Health Aspects of Air Pollution in Europe”; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/air-pollution#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Kang, M.; Zhao, W.; Jia, L.; Liu, Y. Balancing carbon emission reductions and social economic development for sustainable development: Experience from 24 countries. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, E. Sustainability in healthcare: Efficiency, effectiveness, economics and the environment. Future Healthc. J. 2018, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Umair, M.; Khan, S.; Alonazi, W.B.; Almutairi, S.S.; Malik, A. Exploring Sustainable Healthcare: Innovations in Health Economics, Social Policy, and Management. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvard Business School. How to Do a Cost-Benefit Analysis and Why It’s Important. Available online: https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/cost-benefit-analysis (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Kaufman, N.; Barron, A.R.; Krawczyk, W.; Marsters, P.; McJeon, H. A near-term to net zero alternative to the social cost of carbon for setting carbon prices. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Kim, J.; Yang, M. The hidden costs of energy and mobility: A global meta-analysis and research synthesis of electricity and transport externalities. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 72, 101885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Sun, M.; Du, A. Measuring ecological capital: State of the art, trends, and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, F.; Qi, Z.; Cao, W.; Wang, J. Cost-Effectiveness of NOX and VOC Co-operative Controls for PM2.5 and O3 Mitigation in the Context of China’s Carbon Neutrality. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2023, 10, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Ahmed, I.; Khan, K.; Khalid, M. Emerging trends and approaches for designing net-zero low-carbon integrated energy networks: A review of current practices. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 6163–6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.; Heptonstall, P.; Gross, R. Job creation in a low carbon transition to renewables and energy efficiency: A review of international evidence. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Zaman, K.; Nassani, A.A.; Dincă, G.; Haffar, M. Does nuclear energy reduce carbon emissions despite using fuels and chemicals? Transition to clean energy and finance for green solutions. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.A.; Ibrahim, A.J.; Amhamed, A.I.; El-Naas, M.H. Accelerating the transition to a circular economy for net-zero emissions by 2050: A systematic review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, P.F. Strategies of Energy Companies in the Context of a Zero-emission Economy. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2023, 2023, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, M.T.; Mukhtarov, S.; Kirikkaleli, D. Achieving environmental quality through stringent environmental policies: Comparative evidence from G7 countries by multiple environmental indicators. Geosci. Front. 2025, 16, 101956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guingane, T.T.; Bonkoungou, D.; Korsaga, E.; Simpore, D.; Ouedraogo, S.; Koalaga, Z.; Zougmore, F. Evaluation of the Performance of Lithium-Ion Accumulators for Photovoltaic Energy Storage. Energy Power Eng. 2023, 15, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, P.F. Efforts of the transport and energy sectors toward renewable energy for climate neutrality. Transp. Probl. Int. Sci. J. 2024, 19, 170–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzaska, R.; Sulich, A.; Organa, M.; Niemczyk, J.; Jasiński, B. Digitalization business strategies in energy sector: Solving problems with uncertainty under industry 4.0 conditions. Energies 2021, 14, 7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Destek, M.A.; Khan, Z.; Badeeb, R.A.; Zhang, C. Green innovation, foreign investment and carbon emissions: A roadmap to sustainable development via green energy and energy efficiency for BRICS economies. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2024, 31, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepf, V. The dependency of renewable energy technologies on critical resources. In The Material Basis of Energy Transitions; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nwokediegwu, Z.Q.S.; Ibekwe, K.I.; Ilojianya, V.I.; Etukudoh, E.A.; Ayorinde, O.B. Renewable energy technologies in engineering: A review of current developments and future prospects. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anika, O.C.; Nnabuife, S.G.; Bello, A.; Okoroafor, E.R.; Kuang, B.; Villa, R. Prospects of low and zero-carbon renewable fuels in 1.5-degree net zero emission actualisation by 2050: A critical review. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2022, 5, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Zhong, R.; Khan, H.; Dong, Y.; Nuţă, F.M. Examining the relationship between technological innovation, economic growth and carbon dioxide emission: Dynamic panel data evidence. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 18161–18180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.J.; Feng, G.F.; Wang, H.J.; Chang, C.P. The influence of political ideology on greenhouse gas emissions. Glob. Environ. Change 2022, 74, 102496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://esfccompany.com/en/articles/wind-energy/wind-farm-construction-cost/ (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Morthorst, P.E.; Kitzing, L. Economics of building and operating offshore wind farms. In Offshore Wind Farms; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2016; pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Enevoldsen, P.; Koch, C.; Barthelmie, R.J. Cost performance and risk in the construction of offshore and onshore wind farms. Wind. Energy 2017, 20, 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.weforum.org/press/2023/11/net-zero-industry-tracker-13-5-trillion-investment-needed-to-fast-track-decarbonization-of-key-hard-to-abate-industry-sectors/ (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Tumse, S.; Bilgili, M.; Yildirim, A.; Sahin, B. Comparative Analysis of Global Onshore and Offshore Wind Energy Characteristics and Potentials. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, B.; Gebeyehu, D.; Tamrat, B.; Tadiwose, T.; Lata, A. Onshore versus offshore wind power trends and recent study practices in modeling of wind turbines’ life-cycle impact assessments. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2023, 17, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Schindler, D. Efficiency and effectiveness of global onshore wind energy utilization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 280, 116788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Efficiency of the Wind. Available online: https://wxresearch.org/how-efficient-are-wind-turbines/#:~:text=The%20efficiency%20of%20wind%20turbines%20depends%20on%20weather,way%20forward%2C%20especially%20because%20of%20its%20emissions%20benefits (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Soler, A.V. The future of nuclear energy and small modular reactors. In Living with Climate Change; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 465–512. [Google Scholar]

- El-Emam, R.S.; Constantin, A.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Ishaq, H.; Ricotti, M.E. Nuclear and renewables in multipurpose integrated energy systems: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 192, 114157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hee, N.; Peremans, H.; Nimmegeers, P. Economic potential and barriers of small modular reactors in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 203, 114743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Bo, Y.; Lin, T.; Fan, Z. Development and outlook of advanced nuclear energy technology. Energy Strategy Rev. 2021, 34, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuega, A.; Limb, B.J.; Quinn, J.C. Techno-economic analysis of advanced small modular nuclear reactors. Appl. Energy 2023, 334, 120669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhola, S.; Laurila, A.G.; Groundstroem, F.; Klein, J. Climate risks to the renewable energy sector: Assessment and adaptation within energy companies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 1906–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).